The day the Pirates fielded the first all-Black and Latino lineup (original) (raw)

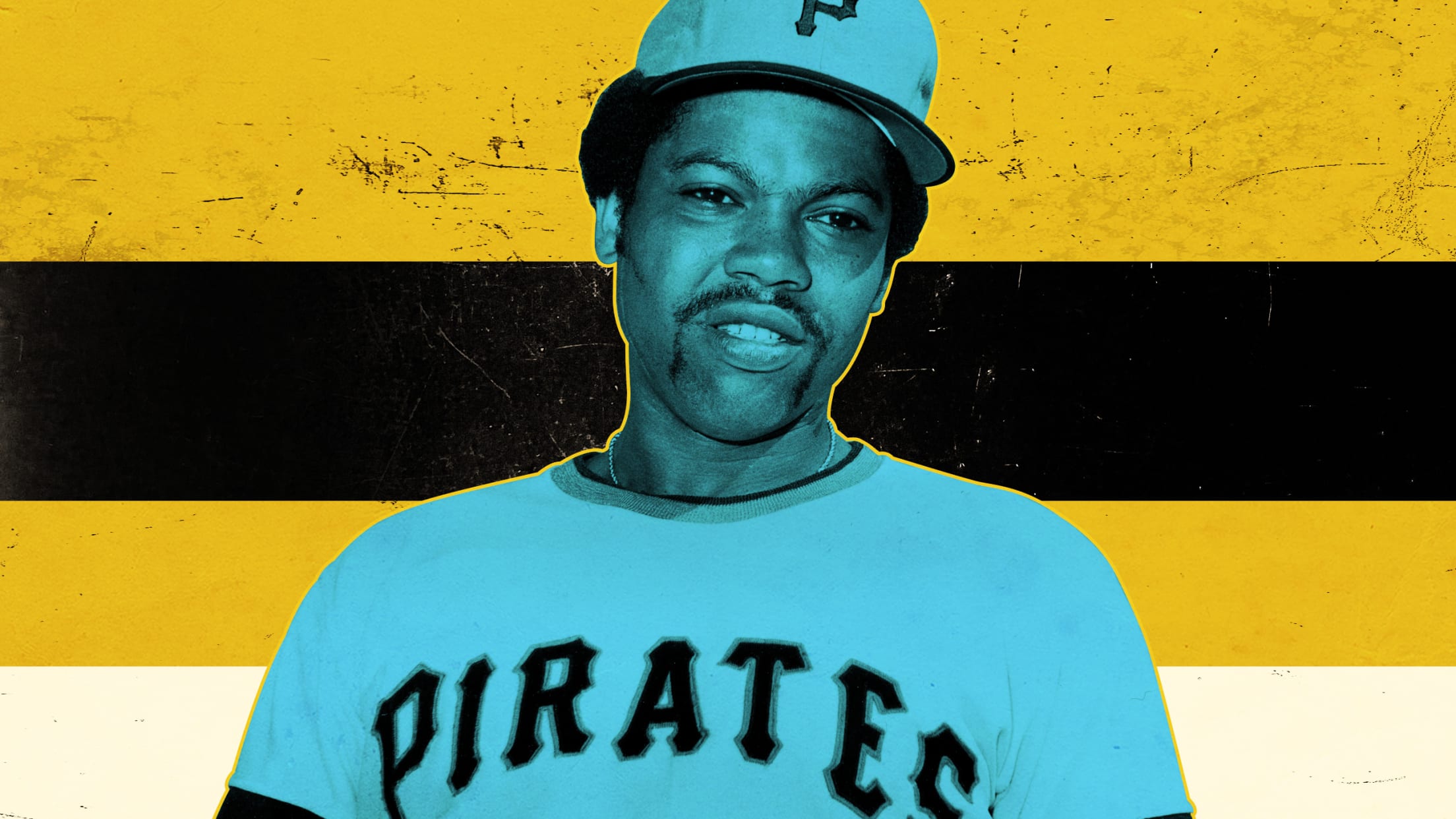

Last Sept. 1 marked the 50th anniversary of when Al Oliver took his position at first base for the Pirates at Three Rivers Stadium in 1971. It was just one of 22 games that Oliver, an outfielder by trade, started at first that season. Oliver went 2-for-4 against the Phillies that night, including a first-inning RBI double that put Pittsburgh up, 3-2. The Pirates won, 10-7.

[A version of this story was originally published in September 2021.]

Yet despite having turned in a solid performance that night, five decades later, Oliver still questions why he was in the lineup.

On the mound for Philadelphia that night was Woodie Fryman, a left-hander. In that situation, Pittsburgh manager Danny Murtaugh would have normally followed conventional wisdom and played the matchup, penciling in Oliver’s platoon partner, the right-handed hitting Bob Robertson, at first base. Instead, it was Oliver, a left-handed hitter, who got the start, batting seventh in a lineup that looked like this:

Rennie Stennett 2B Gene Clines CF Roberto Clemente RF Willie Stargell LF Manny Sanguillén C Dave Cash 3B Al Oliver 1B Jackie Hernández SS Dock Ellis P

That was a key to that whole lineup, that I played first base.

Al Oliver

Murtaugh’s choice of Oliver over Robertston on that Wednesday night might have been inconsequential, except that on Sept. 1, 1971, in front of a crowd of 11,278, the Pirates fielded a lineup composed entirely of Black and Afro-Latino players. It is believed to be the first all-minority starting nine in AL/NL history. Five of those players -- Clines, Stargell, Cash, Oliver and Ellis -- were African American. Clemente hailed from Puerto Rico, Sanguillén and Stennett from Panamá, and Hernández from Cuba.

“That was a key to that whole lineup, that I played first base,” said Oliver.

Injuries may have had a role in shaping the historic lineup. Richie Hebner, who started 93 games for the Pirates at third base that year, was dealing with a viral infection, prompting Murtagh to slide Cash from second to third and pencil in Stennett at second base. Gene Alley, who started 97 games at shortstop for the 1971 Pirates, was sidelined by a sprained knee, so Hernández got the nod.

Per a United Press International story that ran the following day, Robertson was also nursing a knee injury, though it’s unclear if the ailment would have automatically made him unavailable. In fact, Robertson remembers being surprised when he got to the clubhouse that afternoon and didn’t see his name in the lineup against Fryman. He doesn’t recall, however, whether he picked up on the historic nature of the starting nine.

“Maybe when I walked around that corner and my name wasn’t in there, I didn’t scroll the complete lineup,” says Robertson.

Oliver and Robertston, who played together for eight seasons in Pittsburgh, have remained close friends. And all these years later, whenever they see each other, the conversation always turns to Sept. 1, 1971.

“Every time we get together that comes up,” says Robertson.

“WE’VE GOT ALL BROTHERS OUT THERE”

The Pirates’ all-Black and Latino lineup on Sept. 1, 1971, was short-lived. Ellis, who was having an All-Star season and won 19 games that year on his way to finishing fourth in the voting for the National League Cy Young Award, had an uncharacteristic shaky outing, exiting in the second inning after allowing five runs (three earned) in 1 1/3 frames. He was replaced by Bob Moose. (For a brief moment, the Pirates once again had nine Black and Afro-Latino players on the field when lefty Bob Veale replaced Moose with two outs in the top of the third. )

The Pirates’ players on the field did not realize they were making history until the game was underway. Sanguillén remembers hearing about it in the second inning. That’s when, by several accounts, Cash turned to Oliver and said something to the effect of, “We’ve got all brothers out there.”

The game turned out to be a slugfest, with a total of 14 runs crossing the plate in the first two innings. The key hit came off the bat of Sanguillén, whose two-run home run in the bottom of the second gave the Pirates the lead for good.

After the game, reporters asked Murtaugh if he was aware that he had just fielded an all-minority starting nine. According to the UPI story, Murtaugh responded, “When it comes to making out the lineup, I'm colorblind and my athletes know it. They don’t know it because I told them, but they know it because they’re familiar with the way I operate.”

Yet while members of the 1971 Pirates have their doubts that Murtaugh was oblivious to the historic implications of his lineup as he claimed to be -- “He didn’t miss much,” says former Pirates pitcher Steve Blass -- their comments in the years after that game suggest that they believe that the late skipper fielded what he felt was the best starting nine that night.

For Blass, who pitched for Pittsburgh for the duration of his 10-year career from 1964-74, it is entirely plausible that Murtaugh simply believed Oliver was the better option at first base that night. To his point, Oliver performed well against southpaws over the course of his career. His lifetime average vs. left-handed pitchers was .269 with 54 home runs and 397 RBIs in 3,053 plate appearances.

“Al Oliver could hit anybody,” said Blass. “He was that good a hitter. Today, it’s all analytics and the matchups and the previous numbers, but with Danny Murtaugh, I want to speculate that he thought Al Oliver’s talent was good enough to overcome a lefty-on-lefty matchup.”

Oliver agrees.

“He put out the lineup that night that he thought could win the ballgame,” Oliver said. “To this day, I believe that.”

AN UNHERALDED MILESTONE

The Pirates’ all-Black and Latino lineup was a significant milestone for a sport that had admitted its first African American player just 24 years earlier, when Jackie Robinson made his debut for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Yet the historic moment received little media coverage. We are left to wonder if that would have been any different if workers at The Pittsburgh Press and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the city’s two major newspapers, had not been on strike. The work stoppage started in mid-May and ended on Sept. 15.

But papers in Philadelphia and the national media said little about the milestone. In a recap of the game that ran in the Philadelphia Daily News, sports columnist Bill Conlin did make a passing reference to what he called Murtaugh’s “all-soul lineup.”

When we look at the coverage in 1947 of April 16, the day after Jackie Robinson debuted, there were some newspapers that gave it very little play. They treated him as if it was just another rookie making his debut.

Adrian Burgos

In April 1986, former Pirates radio announcer Nellie King told the Pittsburgh Press that he and his on-air partner, Bob Prince, had not devoted too much airtime to the matter. "I don't think we even realized it until the second inning," King said. "We didn't make a big thing about it on the air. We mentioned it, I'm sure, but we didn't dwell on it.”

That same Pittsburgh Press article notes that there was no mention of the historic lineup in the Pirates’ media guide the following year.

Adrian Burgos, a professor of history at the University of Illinois who specializes in minority participation in U.S. sports and is the author of Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line and several other books, believes the lack of mainstream media coverage of the Pirates’ Sept. 1, 1971, lineup reflects a tendency at the time to minimize rather than celebrate the breaking of racial barriers.

“There was a practice among sportswriters -- baseball writers -- during that era to downplay events that we today see as more significant,” said Burgos. “When we look at the coverage in 1947 of April 16, the day after Jackie Robinson debuted, there were some newspapers that gave it very little play. They treated him as if it was just another rookie making his debut.

“What becomes significant to me, particularly as a historian, is thinking about why would they minimize this as a significant occurrence? Why would they not give it more attention? I think one of the factors is because it put the lights back on how long it took for more of Major League Baseball to integrate, and how inactive most sportswriters were in speaking about the racial inequality that existed during that time, that there was a color line.”

Yet there is no overstating the magnitude of the Pirates’ lineup on Sept. 1, 1971, for baseball, which, as Burgos points out, was slow to integrate in the years and decades after Robinson’s debut. Being a Black or Afro-Latino ballplayer in the 1960s and into the '70s still meant being the target of death threats, racial slurs and segregation. The overt racism made it a challenge for Black and Afro-Latino players not only to perform on the field, but to find housing and travel around the country.

Sanguillén, for one, remembers having his life threatened as he walked the streets of Raleigh, N.C., as a Minor League player, among other incidents.

“It wasn’t easy,” he said in Spanish.

It’s hardly a surprise, then, that for Sanguillén and others, the Pirates’ historic lineup on Sept. 1, 1971, was a moment worth savoring.

“African Americans and Latinos saw this, and they saw a great day, a great achievement,” said Burgos. “It was very significant for those communities, because they had been excluded.”

A POWERFUL LEGACY

The ethnic and racial diversity of the 1971 Pirates was, at the time, unmatched in the Major Leagues. With a total of 13 African American and Latino players on their roster, Pittsburgh’s lineups in 1971 were usually heavy on minority players. On nights when Ellis pitched, two-thirds of the starting lineup was usually Black and Latino.

“This is a Black-identified, ‘Black is beautiful,’ ‘Black Power’ kind of team,” said Burgos.

In fact, the Pirates came close to fielding an all-Black and Latino lineup on June 17, 1967, in Philadelphia. In addition to Stargell and Clemente, Pittsburgh’s lineup that day included a pair of Dominican-born players in Matty Alou and Manny Mota; the Puerto Rican José Pagán; and two Black players, Andre Rodgers and Jessie Gonder. However, the starting pitcher -- Dennis Ribant -- was White.

The Pirates’ teams built by Joe Brown, who served as the club’s general manager from 1956-76 and again in '85, were increasingly African American and Latino, reflecting the club’s willingness to acquire and nurture talent regardless of race -- an attitude considered progressive at the time.

Burgos attributes the acceptance that minority players found in the Pirates organization in no small part to Clemente, who by 1971 was the club’s longest-tenured player. Clemente, who had experienced discrimination and racial segregation in his career, was vocal in his demand for respect and equal treatment for minority players, earning the devotion of Sanguillén and many other players from Latin America who came after him.

“The 1971 Pirates showed that you could have stars that are Black and whose clubhouse culture was rooted in accepting everyone on equal footing,” says Burgos. “That’s Clemente’s influence.”

But Burgos notes that what was significant about the Pirates of the late 1960s and ’70s was not just the large number of minority players on the roster, but the fact that two of its clubhouse leaders, Stargell and Clemente -- two of three future Hall of Famers on Pittsburgh’s roster that year -- were Black and Afro-Latino.

“There was so much discussion in baseball circles, in the locker rooms, in the front offices -- can a team be predominantly Black, in its player roster but also in culture and in its leadership, and succeed?” said Burgos. “And what the Pirates showed is that, absolutely [it can].”

A TEAM ON A MISSION

Larry Bowa, the former Major League infielder who went on to manage the Phillies, was in the lineup for Philadelphia the night of the Pirates’ historic lineup. According to him, there was no mention of it in his team’s dugout during the game.

“I don’t remember a word being said about that,” said Bowa. “Looking out there, all I saw was good players.”

Fifty years later, Bowa still marvels at the depth of the lineup that day.

“You’ve got Al Oliver hitting seventh?” he said laughing. “I remember that.”

Indeed, the Pirates lineup that beat Bowa’s Phillies on Sept. 1, 1971, was not just diverse -- it was extremely talented. It featured four of that year’s NL All-Stars: Ellis, Clemente, Stargell and Sanguillén. That night, the Pirates were in the midst of a pennant race with the Cardinals for the National League East Division title.

“It was the perfect mix,” said Blass. “It happened to be Black, White and Latino. But there was one constant, and that was talent.”

The nine players in the lineup on Sept. 1, 1971, helped Pittsburgh win 97 games during a regular season in which no other NL team won more than 90. They went on to beat the heavily-favored Baltimore Orioles, who won 101 regular season games and had four 20-game winners on their pitching staff, in a seven-game World Series.

Fittingly, the 1971 World Series was Clemente’s showcase: He hit .414/.452/.759, collecting a hit in all seven games, with two home runs on his way to becoming the first player from Latin America to claim the World Series MVP Award.

“Beginning in Spring Training, we knew that we had a great team. And our goal was to bring a world championship back to Pittsburgh,” said Oliver.

Now that I’ve thought about it, that’s the best game I caught in the Major Leagues. That’s going to be part of history forever.

Manny Sanguillén

A SHIFT IN PERSPECTIVE

Precisely because the Pirates often fielded diverse lineups, the all-Black and Afro-Latino starting nine on Sept. 1, 1971, wasn’t all that surprising to Oliver at the time.

“To us, it was no big deal, because we had so many minorities on our team,” he said.

Yet Oliver’s appreciation of the history he was part of has grown over the time. To him, the game carries greater significance now than it did on a late summer night 50 years ago. A motivational speaker, Oliver often cites the Pirates’ all-Black and Latino lineup in his talks. And he laments that the historic game is rarely discussed.

In Oliver's opinion, as far as social baseball milestones go, the Pirates’ all-Black and Latino lineup ranks second only to Robinson’s debut.

“How can anyone forget that night?” said Oliver. “As far as minorities in sports, that has to be second.”

Similarly, in hindsight, Sanguillén says he now ranks the Sept. 1, 1971, game over his two World Series appearances.

“Now that I’ve thought about it, that’s the best game I caught in the Major Leagues,” said Sanguillén. “That’s going to be part of history forever.”