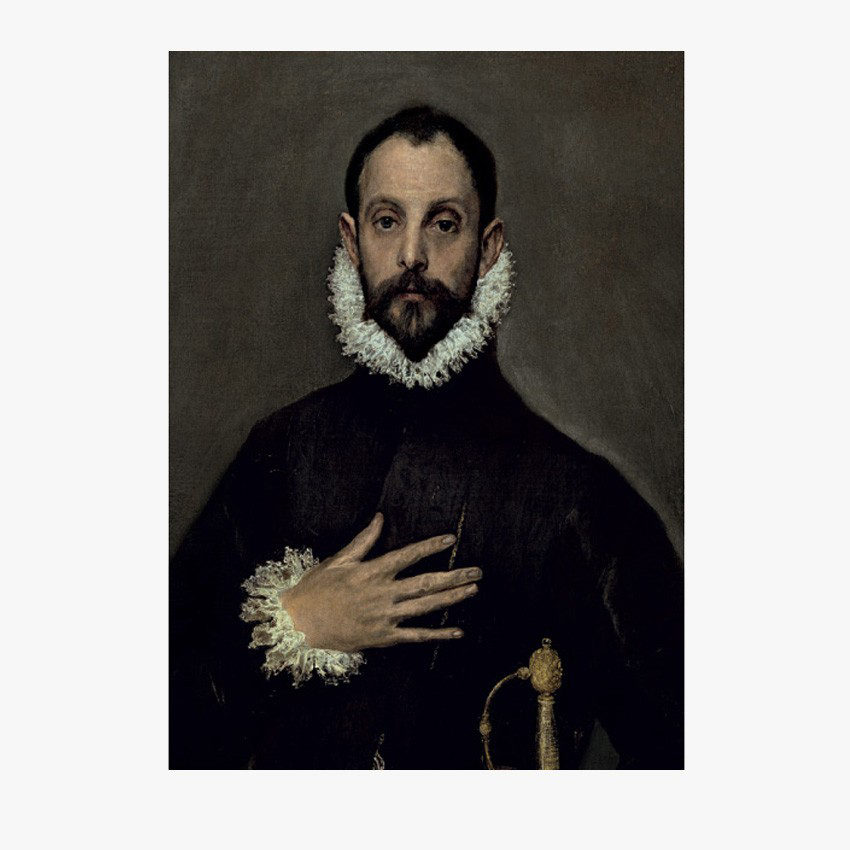

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) - The Collection (original) (raw)

Candia, Crete (Greece), 1541 - Toledo (Spain), 1614

This Spanish painter of Greek origin was born in the capital city of the Isle of Crete, which then belonged to the Republic of Venice. His family was Greek, but probably Catholic rather than Orthodox, and its members collaborated with the colonial powers. He was trained as an Icon painter in the late-Byzantine tradition, but contact with Italian engravings allowed him to absorb and partially employ some of that country’s Renaissance formulas. He was already a master painter by 1563, and in 1566 he requested permission to have an icon of the Passion appraised so that he could sell it at a lottery. In 1567 he moved to Venice, where he resided until 1570 and, while he did not actually apprentice to Titian, he was able to learn that artist’s style from outside his studio. In that city, he gradually mastered Western art and the Renaissance Venetian approach to color, perspective, anatomy and painting with oils, although he never completely abandoned his traditional practices. After a study trip through Italy (Padua, Vicenza, Verona, Parma, Florence), he settled in Rome, where he remained until 1576-1577. As part of the intellectual circle around Cardinal Alejandro Farnesio, in whose palace attic he initially lodged, he was in close contact with a number of Spanish clergymen and literati. In 1572, he was expulsed from the cardinal’s service and joined the Roman Guild—the Academy of San Lucas—which allowed him to open his own workshop. From then on, he concentrated mainly on portraits and small religious works for private clients, adopting a much more Italianate and advanced style. He must not have been as successful as expected, however, as he decided to emigrate. And, while we do not know his exact reasons, it has been hypothesized that he moved to Spain with the intention of working for King Philip II, as the monastery of El Escorial was being decorated in the spring of 1577 and the artist was already there at that time. He later moved to Toledo, where the cathedral and the monastery of Santo Domingo el Antiguo commissioned him to paint the first canvases documented here. For the former, he painted The Disrobing of Christ; and for the latter, three altarpieces, including two canvases now at the Museo del Prado. He arrived in Spain with a young Italian assistant, Francesco Prevoste, who remained with him until his death. The artist’s son, Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli (the Italianized form of his surname employed in Spain), was born in 1578 as the result of a brief relationship with Jerónima de las Cuevas, a woman who came from Toledo’s community of craftspeople. Domenikos Theotokpoulos, “El Greco”, remained in Toledo for the rest of his life, travelling very little, and always for work. His life was uneventful, except for nine documented lawsuits brought by him or by some of his clients. Some of these had to do with the value and price assigned to his works by assessors; others were for technical or iconographic reasons and involved works from both the beginning and end of his career, including The Disrobing of Christ, and a Martyrdom of Saint Maurice for one of the altars at the basilica. El Greco expanded his workshop to include the production of not only canvases but whole altarpieces for monasteries, parishes and chapels, including successive projects for the parish of Talavera la Vieja (Caceres), the chapel of San José and the Chapel of the Collegiate Church of San Bernardino in Toledo, the Collegiate Church of la Encarnación or of doña María de Aragón in Madrid, the church at the Hospital of Nuestra Señora de la Caridad in Illescas, the Oballe Chapel at the parish of San Vicente Mártir, and those at the Hospital of San Juan Bautista or Tavera, also in Toledo, which was unfinished when he died. He also contracted projects, sometimes with his son, that he never managed to carry out, including the royal monastery of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (Caceres). In some of these latter works, El Greco favored innovatively designed and plural artistic combinations that included sculpture and altarpiece architecture along with his paintings and other canvases set into the walls or domes. These complex formal and visual systems must have produced fascinating effects, although today it is difficult to find any of them in their original state. So, in fact, he was designing sculptures and architecture, and he took a particular interest in the latter throughout his career in Spain. While he never actually designed a building, he was frankly opposed to the reigning local postulates determined in Madrid by royal architect Juan de Herrera and applied in Toledo by the latter’s acolytes. In a refined atmosphere where he probably spent more that he was earning, and surrounded by Toledo’s academic intellectuals and a small circle of Italianized and Hellenistic friends, El Greco died intestate on April 7, 1614. He left a body of work praised by culteranist poets Luis de Góngora and Friar Hortensio Félix Paravicino and collected by art lovers. Considered a singular and paradoxical “extravagant” for his theories and a highly personal and immediately identifiable style, he was greatly admired by his colleagues for his efforts to dignify the painter’s profession. He was, however, criticized by the most intransigent counter-Reformist theorists for his formal and iconographic license in matters of tone, composition and detail. They also rejected his disproportionate interest in superfluous formalist aspects of his work and the character of his religious images, which they considered inappropriate for what was then their most important function: encouraging the viewer to pray, as the Hieronymite historian from El Escorial, Friar José de Sigënza, pointed out. Repudiated by the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, he was rediscovered by the Romantics and by 19th-century French painters who interpreted him according to their own interests. That, too, was the period when Spain began to consider him a Spanish artist, rather than identifying him as a Greek disciple of Titian. Widespread interest in Velázquez’s painting also drew attention to this artist from Candia, who can be considered the only truly original forerunner to the Sevillian master in the history of Spanish painting. For the Generation of ’98, he embodied Siglo-de-Oro Spain’s religious spirit, closely related to that epoch’s religious zenith in the mystical poetry of Santa Teresa de Jesús and San Juan de la Cruz. Early 20th-century painters saw him as a forerunner to their expressionist, subjectivist and tormented concerns, and the freedom with which they rejected a servile and mechanical imitation of reality. Today, the interpretation of El Greco’s painting is once again undergoing renewal and debate. His ties to the spirituality of the Barefoot Carmelites and his identification with Spanish values are being questioned in light of his artistic and cultural Italianism, the underlying Greek stratum, and the philosophical character of his art. This questioning focuses on his interest in its formal and beautifying function as a means of knowing Nature. Rather than a mystical and possessed artist, he is now seen as an aesthetic, intellectual and philosophical painter free of the concerns of his devout and erudite contemporaries. He may have collaborated willingly with, and insightfully interpreted, the counter-reformation Catholic interests that held sway in Spain under Philip II and Philip III, but he may also have ignored their concerns, focusing exclusively, and against the grain, on the development of a personal, formalist style that reflected theoretical postulates on art visible in the notes he jotted in books from his impressive library, including Giorgio Vasari’s Lives or Vitruvio’s Architettura. These varied possibilities constitute a logical response to an artist already considered singular and paradoxical in his time, and they bear witness to the interest his work has generated among critics and historians of art and culture, as well as in any viewer who approaches his work and experiences the attractive if disconcerting effects of his painting. The Museo del Prado also has canvases from the Altarpiece of the Collegiate Church of the Augustine Nuns of Doña María de Aragón (1596-1600), the Annunciation, the Baptism of Christ and the Crucifixion, as well as two depictions of The Resurrection of Christ and the Pentecost, whose assignment to this altarpiece is very disputable. His later Adoration of the Shepherds (1612) comes from his Funerary Altarpiece of Santo Domingo el Antiguo. Other works, besides some devotional images of unidentifiable provenance, include four paintings from the Almadrones Apostolate (Guadalajara), which is thought to have been initiated by El Greco and concluded after his death by his son, Jorge Manual and members of his Toledo workshop. These are thus very late and restored works (Marías, F. in E.M.N.P., Madrid, 2006, vol. IV, pp. 1228-1232).

}

Multimedia

Contemporaries

Prado Shop

TEXTILE & APPAREL

STATIONERY

Print on demand

Print artworks available in our catalogue in high quality and your preferred size and finish.

Image archive

Request artworks available in our catalogue in digital format.