Inside the historic decision to deep-select the Navy’s top officer (original) (raw)

On the morning of Feb. 18, 1991, the guided-missile cruiser Princeton inched closer to the Kuwaiti shoreline, using the world’s most advanced sensors to sniff for Iraqi Silkworm sites, transforming itself into what its crew called a “missile sponge” to protect a gathering armada behind it.

Then two explosions erupted under the port rudder and near the starboard bow and everyone went to general quarters on a cruiser dead in the water.

Three sailors were wounded. Damage control teams rushed to contain the deluge from internal pipes that broke open. A cut in power stopped the air conditioning, which knocked out the Aegis radar and Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles, leaving the mighty warship defenseless.

Lt. Michael Martin Gilday was the tactical action officer on a vessel that struck two of the 1,000 mines strung in an underwater arc stretching 150 miles, from the Persian Gulf’s Faylaka Island to the Saudi border, officials later determined.

But 15 minutes after the detonations, Gilday and his crew had restored the TLAM and Aegis systems and returned the Princeton to its place as the flotilla’s anti-air ringleader.

And they remained at their battle stations for another harrowing 30 hours until the wounded warship could be towed out of the minefield, according to the citation attached to his 1991 Navy Commendation Medal with Valor device, which notes his courageous leadership.

“He was responsible for our command and control of our communications with the rest of the world, as well as the security of the combat systems,” said retired Capt. Edward B. “Ted” Hontz, the commander of the Princeton during Operation Desert Storm.

“He was a wartime guy and did a superb job,”

Gilday “took care of his job,” Hontz continued. “He took care of his people, extremely professional. He was a calm, cool customer, and at the time — in my opinion as an officer at the end of my career — was ... as cool a character as you can get, he’s so good.”

Hontz pegged Gilday as a future three-star but conceded “it appears he’s going to exceed my hopes.”

With the use of hand flares, the minesweeper Adroit marks possible mines in an effort to extract the already damaged guided-missile cruiser Princeton from a minefield. The salvage and rescue ship Beaufort stands by to assist. (Painting by John Charles Roach/ U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command)

On Aug. 1, the U.S. Senate unanimously confirmed Gilday as the 32nd chief of naval operations and granted him a fourth star.

He’d been deep-selected from the ranks of vice admirals, a promotion unseen since 1970 but one that surprised few of those who’ve watched him rise from a lowly U.S. Naval Academy plebe 38 years ago.

“The most important thing is, if there’s there’s an officer who walks on water, who’s a superstar, usually there’s an element of ego that goes along with that. And you never got that from Mike,” said Joe Wright, an Academy classmate and the navigator of the Princeton off the coast of Kuwait.

And he has a story about Gilday’s valor award, too.

“So we were in the CO’s cabin,” Wright recalled. “This was after everything that happened. And we’re in dry dock in Dubai. And I happen to notice, there was a clipboard with a list of names and proposed decorations for people. And I saw it was there. Then I saw Mike pick it up and crossed off his own name.

“And I don’t think he knew that I saw him do that.”

Then-Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Bill Moran in Times Square on May 25 during Fleet Week. (Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Kyle Hafer/Navy)

Bad Santa

Gilday, 56, never could have anticipated his rapid elevation to replace Adm. John Richardson, who is retiring as the sea service’s top officer.

A change of command ceremony had been planned for Aug. 1 in Annapolis, with former Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Bill Moran fleeting up to become CNO.

Confirmed without a whiff of scandal by the Senate, Moran was derailed by reports of an ongoing Pentagon probe into emails he allegedly exchanged with his former spokesman, Chris Servello.

Although he was never charged with a crime and has long professed his innocence, Servello’s own career foundered in late 2016 after he was accused of sexually-tinged shenanigans while dressed as Santa Claus at a boozy Pentagon holiday party.

A surprise July 7 announcement by Secretary of the Navy Richard V. Spencer axed Moran’s promotion and began a process to find his replacement.

Spencer told Navy Times that he and CNO Richardson didn’t want to dragoon one of the Navy’s eight four-stars on active duty, believing that they held critical billets overseas and at home and couldn’t be replaced.

Spencer believed there was “a pretty good bench” of vice admirals but Gilday — the director of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for a year — “started shining like a diamond.”

Spencer was drawn to the four years Gilday spent at Cyber Command inside Maryland’s Fort Meade before he went to the Pentagon. He wanted to find someone with an acute knowledge of cyberwarfare as his next CNO.

But first he had to canvass the opinions of former SECNAVs and CNOs about Gilday. When they heartily endorsed the vice admiral, Spencer began talking to four-stars outside the sea service, too.

The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Marine Gen. Joseph F. Dunford Jr., told him, “I’d never let him go for any other opportunity but to help the Navy in the position of CNO,” Spencer recollected.

Gen. David L. Goldfein, the Air Force’s chief of staff, strongly supported Gilday’s promotion and so did his counterpart in the Army, Mark A. Milley, who was soon to be confirmed as Dunford’s replacement.

“All the marks came back A+,” Spencer said.

But in the back of his mind, Spencer still struggled with deep-selecting a three-star for CNO, something that hadn’t been done since Secretary of the Navy John Chafee and President Richard Nixon recalled Vice Adm. Elmo “Bud” Zumwalt Jr. from Vietnam to serve as the top naval officer.

Zumwalt leaped over 33 more senior officers but proved Chafee right. Today he’s remembered as one of the most inspiring and innovative CNOs to have held the post.

A Marine Corps veteran, Spencer told Navy Times that he couldn’t be blind to naval history and tradition, and choosing Gilday became a “weighty” decision “because this was a significant movement.”

Convinced that Gilday was the best officer for the job, he took his proposal to the Pentagon and the Oval Office.

He said that President Donald J. Trump also understood the historical moment and wanted consensus from his military leaders that this three-star was the right person.

The president said, “Got it. Understood,” Spencer recalled.

They had their nominee.

Adm. Elmo R. Zumwalt speaks with the Human Relations Council, at Fleet Activities Yokosuka in Japan on July 2, 1971. A deep selection recalled from Vietnam to serve as CNO, Zumwalt left a lasting legacy on the sea service. (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command)

Historical moment

Retired Adm. Jim Stavridis was NATO commander when then-Rear Adm. Gilday served on the staff of the Allied Joint Force in Lisbon.

A student of history, Stavridis isn’t surprised by Spencer’s decision to elevate Gilday because he sees signs of both Zumwalt and Arleigh Burke in the new CNO’s career.

Dwight D. Eisenhower promoted Rear Adm. Arleigh Burke over 92 flag officers to become his CNO in 1955.

“He has the innovation credentials of Zumwalt in his work as 10th Fleet commander on cyber, especially in harnessing it for offensive operations. His distinguished destroyer background is reminiscent of Arleigh Burke,” said Stavridis.

Before he commanded Carrier Strike Group 8, Gilday led Destroyer Squadron 7 and the Arleigh Burke-class destroyers Benfold and Higgins.

“But ultimately, he is his own distinct leader, and his defining quality is humility. Quiet, thoughtful, kind, and blessed with a self-deprecating sense of humor, he leads without ego or hubris. He is a perfect choice as CNO for today’s Navy,” Stavridis said.

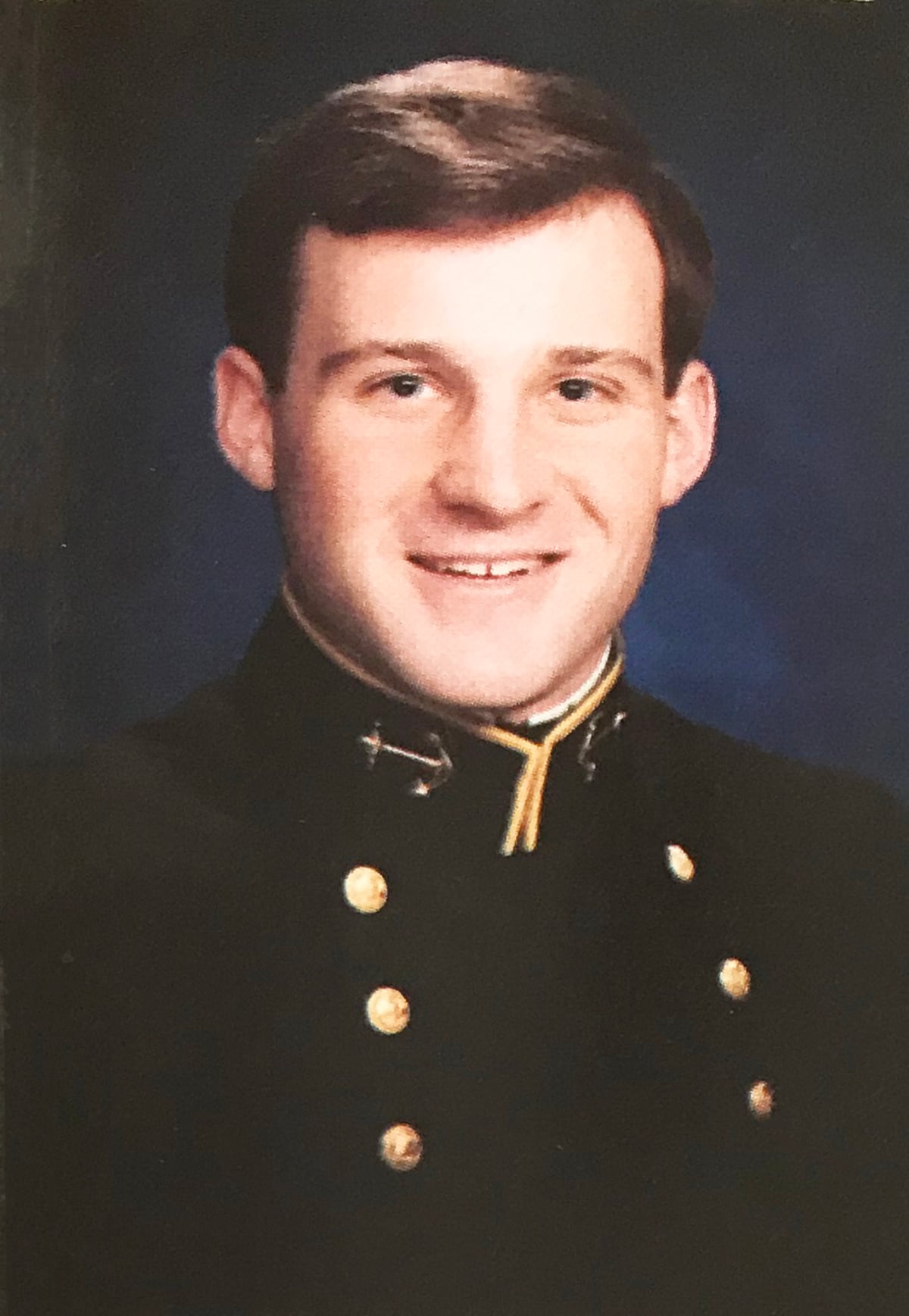

Midshipman Michael Gilday (U.S. Naval Academy)

Son of a sailor

That self-deprecation might stem from his blue collar roots, sailors and officers told Navy Times.

Gilday is the son of a sailor, and he grew up in an Irish Catholic family of five in Lowell, Massachusetts, according to his Naval Academy yearbook.

In Annapolis, he was known as “Crash” or “Squire Mike,” the sort of midshipman who drank 10,000 cups of coffee and dipped a thousand cans of Copenhagen before he graduated.

And graduation in 1985 didn’t always seem a likely outcome.

The yearbook notes that he was sent to “ac-board,” an academic program to shore up substandard performance, before he put it all together and stitched on three stripes as the regimental adjutant — a top leadership post for midshipmen — and made the superintendent’s list of top performers.

“He probably wasn’t the smartest of the guys in our company but by any measure he was probably the hardest working of all of us put together,” said classmate Dan Holzrichter, who commissioned as a Marine.

“He was a very intense person, too, whether it was studying or playing ultimate frisbee. Whatever he did, he brought that intensity to it.”

Along with the intensity came attention to detail.

“You would open up his medicine cabinet and everything would be lined up, from smallest to largest. So if you wanted to mess with him, you’d move things around,” Holzrichter said.

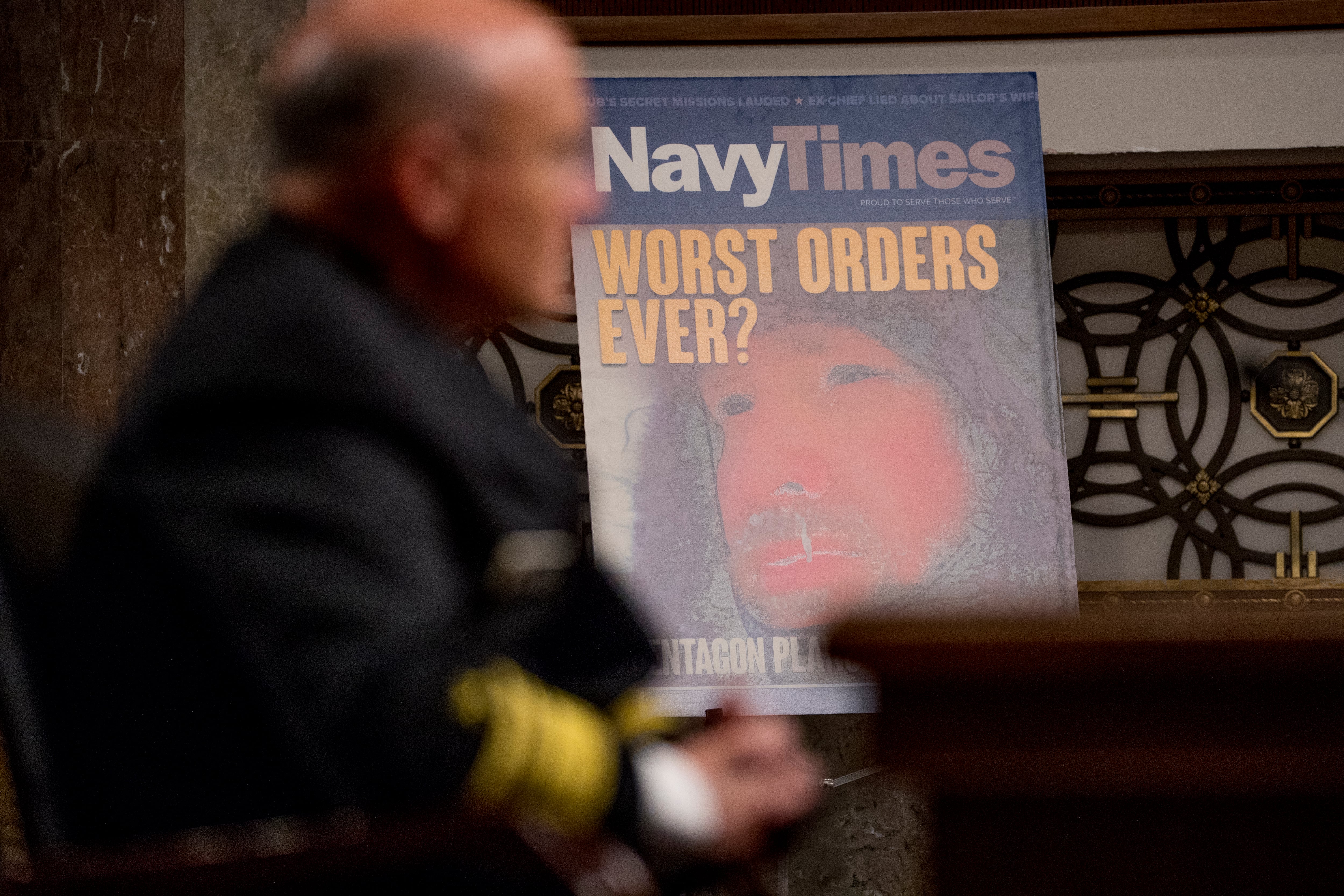

A poster of a Navy Times cover titled "Worst Orders Ever?" is propped behind then-Vice Adm. Michael Gilday during his July 31 testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee on Capitol Hill. ( Andrew Harnik/AP)

In the fleet

All the traits that made Gilday a successful midshipman followed him to the fleet after he commissioned as a surface warfare officer.

Three years behind him at the Academy, Jerry Dickerson was a lieutenant junior grade serving as the officer of the deck when Princeton detonated the two manta mines in 1991. When they went to general quarters, he reported to Gilday inside the Combat Information Center — the electronic nerve center of the warship — and watched his leadership under pressure.

“He always led by example, from out front, and there was no tolerance for us not performing at a very high level. It was very clear all the time, I felt, that I was being led by Mike Gilday. But his leadership wasn’t in a dictatorial way. It was kind of a ‘I’m going to lead from out front and you guys better keep up with me’ kind of style,” Dickerson recalled.

By the time Gilday rose to executive officer on the sister Ticonderoga-class cruiser Gettysburg, he’d evolved into a highly intelligent and inspiring leader, retired Rear Adm. Jacob Shuford, the warship’s former CO, recalled.

Shuford commanded three vessels and a strike group and never met a better XO or chief of staff.

“He’s really an extraordinary person,” Shuford said. “He’s smart as a whip, really knows the Navy and has a strong set of values he’s developed in his life. You put someone like that in any job and they’re going to be great. And, of course, he would be the last to toot his own horn. In fact, he doesn’t do it at all. That’s Michael Gilday.”

RELATED

Sailors who served below Gilday told Navy Times the same thing.

“I was simply not surprised to hear that he had been selected as a three-star to be CNO,” said retired Command Master Chief Michael DiBiccaro, his top enlisted adviser on the destroyers Higgins and Benfold.

“When we worked together years ago, I knew he was going places. You can see the impression he makes on people. You just can’t fake that.”

DiBiccaro recollected that Gilday hated pomp, a departure from a previous CO whose movements through a warship could be traced by all the sailors shouting “Attention on deck!” or “Gangway!”

Under Gilday, they only announced his arrival during special events, like award ceremonies. DiBiccaro said that he didn’t want to interrupt sailors at work.

In 18 months under his command, he can’t remember the officer ever raising his voice — because he never needed to do it.

Gilday confided to his command master chief that he understood the importance of maintaining discipline, but the one job he truly hated was holding Captain’s Mast. After doling out the punishment, he privately worked with his enlisted leaders to “get this sailor back on board.”

“And even for those sailors who did something that required us to send them home, he’d tell me ‘I know that has to happen, we can’t have that in the Navy, so we punish the sailor. But let’s make sure we take care of the human being on their way out,’” DiBiccaro said.

“I’ve worked with some great officers, officers that have gone on to become admirals and command ships, and all those things,” DiBiccaro continued. “I knew when I left that ship, that he was finest naval officer I’ve ever served with. I have never met a sailor, officer or enlisted, that did not respect him and did not love him.”

About Mark D. Faram

Mark D. Faram is a former reporter for Navy Times. He was a senior writer covering personnel, cultural and historical issues. A nine-year active duty Navy veteran, Faram served from 1978 to 1987 as a Navy Diver and photographer.