"Queercore": A decades-old movement for gay punks, freaks and rebels (original) (raw)

The rejection of mainstream gay culture and the full-throttled embrace of an alternative to the fight for widespread acceptance are among the defining characteristics of a queer underground scene born in the 1980s with punk rock roots.

Directed by Berlin-based filmmaker Yony Leyser, “Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution” is a feature-length snapshot into the music and magazines that gave voice to LGBTQ outsiders — those who didn’t subscribe to the dominant gay scenes erupting in vogue dance or macho dress, for example.

“I was always a freak,” Leyser, 32, told NBC News. “I dressed different. I thought different. I was always rejected by society, and I also felt rejected by the gay community. I didn’t want to go to the shopping mall and buy a Tommy Hilfiger polo shirt. I didn’t want to get a tan and spend my whole day at the gym. I wanted to be an activist. I wanted to go to rock shows. I wanted to make art.”

“Queercore,” or “homocore,” is the gay punk movement that provided an answer.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, most notably in Toronto but with origins elsewhere, an underground culture was formed by a revolutionary group of self-proclaimed “queers” who were less concerned about mainstream acceptance of their sexuality and more geared toward creating unconventional spaces where they could be themselves. Places where, essentially, one could be gay without liking stereotypical “gay things.”

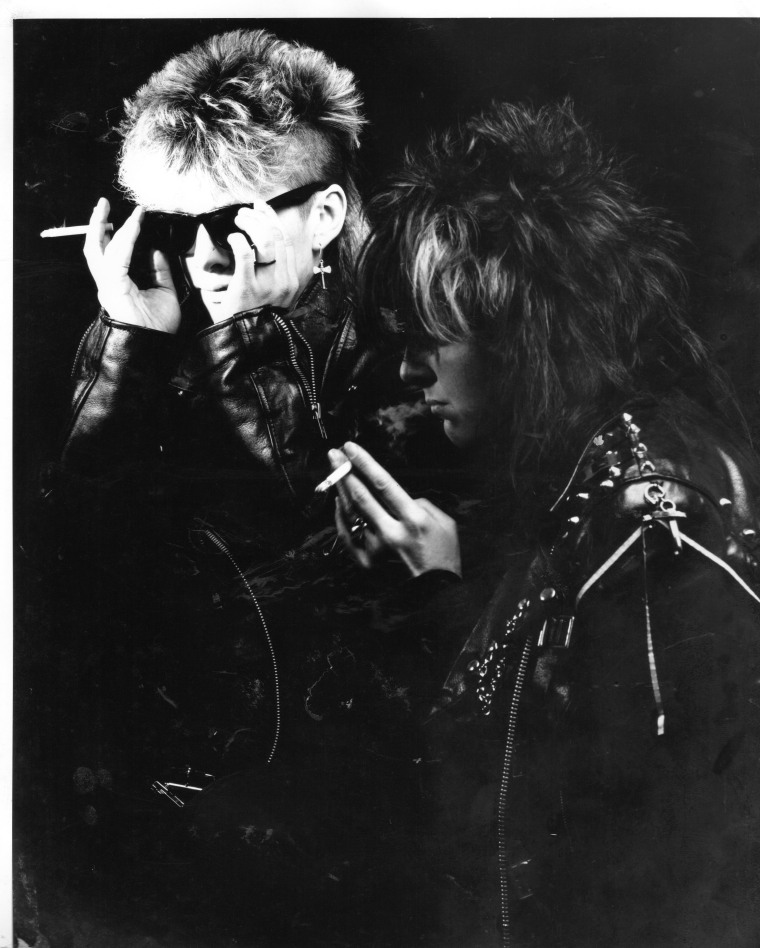

Production still from the documentary "Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution"Desire Productions / Totho

A scene that took notes from the sexually liberating roots of punk, queercore was a movement that refused the status quo of belonging, which other LGBTQ communities were striving for, embracing negative gay stereotypes in a spectacle of experimental film, alternative magazines and, of course, music.

“I saw that community still existed,” said Leyser, who, as part of research for his film, went on a U.S. tour with the queer rebel writer group Sister Spit. “There are activists, punks, freaks and rebels that don’t want to participate in mainstream culture and don’t want to participate in being accepted. They would rather embrace being an outsider. So I felt this urgency to document this part of history.”

While having grown up in Chicago nearly a decade after his documentary’s timeline starts, Leyser’s experience of social isolation mirrors that of his film’s protagonists, Bruce LaBruce and G.B. Jones, who in the 1980s were two twentysomethings living in Toronto who liked rock music and embraced their queerness.

But LaBruce, now a well-known filmmaker and provocateur, and Jones, one of the founders of the all-female, post-punk band Fifth Column, didn’t exactly identify with gay culture at the time, relating more to the anti-establishment call of the punk movement.

Related: 20 Films Women Will Love at LA's Outfest LGBTQ Film Festival

Being gay in the late ‘80s, particularly in metropolitan areas like Toronto, New York and San Francisco, was, as LaBruce describes in the film, “bourgeois” and “conventional”, while also placed on a backdrop engulfed by the AIDS epidemic.

The terror that was AIDS amplified the social stigma already associated with homosexuality, spawning efforts to normalize same-sex relationships through organizations like Queer Nation.

Queer Nation, which was birthed in 1990 as a militant response to LGBTQ prejudice, demanded equal rights for gays and lesbians, which, like other LGBTQ activist groups, could eventually be viewed as an assimilation into mainstream society, and thus, capitalism. This was an ideology that queercore wanted to distance itself from.

The Pride Punx float at the London Pride Parade on July 8, 2017.Derek Bremner

“Punk in its very essence is queer,” said Tali Clarke, a London-based filmmaker and creator of the Pride Punx float, which recently took part in London’s annual pride parade. “It’s no labels, open and accepting and very anti-homophobic and anti-racist. In its essence, LGBTQ culture strives to be accepted and commercialized in the mainstream consciousness. Punk rock and alternative culture wants the very opposite of that.”

Early punk bands and performers of the 1970s — like Nervous Gender, Catholic Discipline and Patti Smith — flipped gender roles on their head, criticizing the definitions of masculine and feminine within contemporary culture and their laws aimed at controlling sex.

But by the ‘80s, punk had changed to a more hardcore sound and the once inclusive counter-culture suddenly became filled with homophobia, sexism and “macho punks.”

“People think skinheads are racist and actually the original skinheads are completely entrenched in Caribbean culture,” said Clarke, 32. “Nazi punks and regular punks don’t get on, but they’re both claiming the same culture and yet have completely different ideals.”

This attack on the punk ethos inspired LaBruce and Jones to release the zine “J.D.s” — a photocopied magazine that’s style is a collage of images and text, distributed at publishing fairs, record shops and concerts. “J.D.s” took a position against this new wave of punk rock, which embraced homophobic songs and excluded LGBTQ people. The zine also included radical ideas and pornography and gave the reader the perception that queer punks were an international phenomenon.

“Out of bravado, they got a bunch of straight punks drunk, put instruments in their hands, took pictures, made up band names and just created the scene that they wanted to be apart of,” Leyser said of this new wave. “It was a joke but people believed it and a scene sprung up.”

Other zines followed “J.D.s” — including San Francisco's “Homocore" — and helped solidify a place for LGBTQ people within punk culture, just as feminist punk movements like Riot Grrl did the same for women.

Models Pom and Trill in "Rebel Dykes," an upcoming documentary about punk lesbians in 1980s London.Siobhan Fahey

“I was a rebel dyke,” said filmmaker Siobhan Fahey, whose upcoming film “Rebel Dykes” documents punk lesbians living in London during the 1980s. “I felt very excluded from mainstream society but also from the more respectable lesbians, who came from the’ 70s, were a lot more academic but had, what we thought, were some problematic politics. They were very separatist and quite anti-men, and we just wanted to have a lot of fun, do drugs and have lots of sex, which they seemed to disapprove of. So we created our own scene.”

Exclusion from both of these spaces and the opportunities missed because of this sparked a freedom to create new worlds, where one could live by his or her own rules and be supported by a likeminded community.

Leyser’s film is packed with archival footage and fresh interviews that educate his audience about queercore’s cultural significance. Southern California bands like Tribe 8 and Pansy Division, which would lay the groundwork to influence others like Green Day, Nirvana and Peaches, are among the groups featured in the film. These bands turned sexuality upside down, offering alternative representations to the mainstream, most noted today by transgender woman Laura Jane Grace, the lead singer of Against Me!.

“I think [the film] has a mainstream appeal,” said Leyser, having premiered “Queercore” at UK’s Sheffield Doc/Fest in June. “I think the audience is maybe more for music lovers, than LGBTQ. I really think it’s a film for everyone. It’s a global story about creating a revolution for everyone and seeing that these people were able to do that.”

Decades after its inception, queercore continues to rebel against gender politics and the commodification of homosexuality, seen earlier this year by the uproar caused by Gucci’s “Queercore” shoe collection and Facebook’s apparent censoring of the word “dyke.”

Follow NBC Out on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram

Catherine Chapman

Catherine Chapman is a London-based journalist.