'Climate grief': The growing emotional toll of climate change (original) (raw)

When the U.N. released its latest climate report in October, it warned that without “unprecedented” action, catastrophic conditions could arrive by 2040.

For Amy Jordan, 40, of Salt Lake City, a mother of three teenage children, the report caused a “crisis.”

“The emotional reaction of my kids was severe,” she told NBC News. “There was a lot of crying. They told me, 'We know what’s coming, and it’s going to be really rough.’ “

She struggled too, because there wasn't much she could do for them. “I want to have hope, but the reports are showing that this isn’t going to stop, so all we can do is cope,” she said.

The increasing visibility of climate change, combined with bleak scientific reports and rising carbon dioxide emissions, is taking a toll on mental health, especially among young people, who are increasingly losing hope for their future. Experts call it “climate grief,” depression, anxiety and mourning over climate change.

Last year, the American Psychological Association issued a report on climate change’s effect on mental health. The report primarily dealt with trauma from extreme weather but also recognized that “gradual, long-term changes in climate can also surface a number of different emotions, including fear, anger, feelings of powerlessness, or exhaustion.”

In the last few months, a string of reports have delivered dire warnings. The U.N. report said the worst effects — such as the flooding of coastal areas caused by rising sea levels, drought, food shortages and more frequent and severe natural disasters — could arrive as soon as 2040. In November, the Trump administration released a report with similarly alarming findings. Both reports said cutting greenhouse gas emissions could still avert many of these effects, but a study earlier this month found that after holding steady from 2014 to 2016, emissions rose in 2017 and are on course to hit an all-time high in 2018.

The reports came amid a string of powerful natural disasters, including some that wiped out entire communities, such as Paradise, California, incinerated by the Camp Fire, and Mexico Beach, Florida, washed away by Hurricane Michael.

According to a Yale survey taken this year, anxiety is rising in the U.S. over the climate. Sixty-two percent of people surveyed said they were at least “somewhat” worried about the climate, up from 49 percent in 2010. The rate of those who described themselves as “very” worried was 21 percent, about double the rate of a similar study in 2015. Only 6 percent said humans can and will reduce global warming.

Dr. Lise van Susteren, a psychiatrist in Washington and co-founder of the Climate Psychiatry Alliance, said it’s becoming harder for patients to ignore the threats of climate change.

“For a long time we were able to hold ourselves in a distance, listening to data and not being affected emotionally,” she said. “But it’s not just a science abstraction anymore. I’m increasingly seeing people who are in despair, and even panic. “

A 10-Step Program for Climate Grief

After the U.N. report was released, Jordan looked for a way to help her children cope. She saw a sign at her church for a support group that deals with the issue, the Good Grief Network.

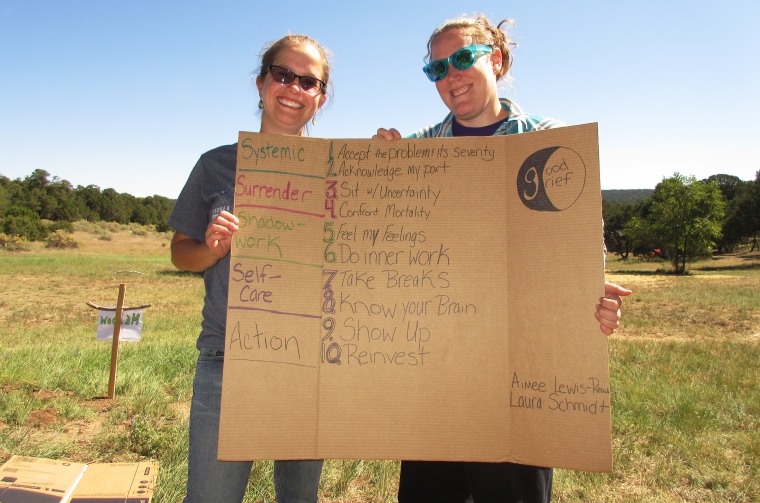

Founded by Aimee Reau, 30, and LaUra Schmidt, 32, Good Grief offers a 10-step program to help people deal with collective grief — issues that affect a whole society, like racism, mass shootings and climate grief.

The program runs as a 10-week cycle, each weekly meeting tackling a different step. It’s currently in its third cycle in Salt Lake City and is also running online. The steps encourage participants to confront their climate fears and sadness and acknowledge that they are part of the problem as polluters in a carbon-fueled system, but also find the motivation and strength to be part of the solution.

“What helps people is building community, talking openly about the problem and how it affects them,” Schmidt told NBC News. “There’s a lot of pain about the climate people are bottling up.”

For Jordan, who works as an interpreter of American Sign Language, the program has been helpful.

“Grieving with other people is so healing, being able to talk openly and cry it out,” she said. “We look each other in the eye and say, ’this is really happening.’ ”

Jordan plans to bring the program back to her family and hopes that it will help her kids cope. “They express sadness over the loss of animal species and anxiety over the unknown, like if there will be enough food in the future and where people displaced by rising seas will live,” she said.

In September, Reau and Schmidt presented their program at Uplift Climate, an annual conference on climate change for people under 30, held entirely outdoors. This year’s event was held in New Mexico’s Cibola National Forest.

Aimee Reau, left, and LaUra Schmidt, creators of the Good Grief Network, hold a sign listing their 10 steps to deal with climate grief at the Uplift Climate conference in September.Avichai Scher / For NBC News

“Is this the climate change depression session?” asked Kelton Manzanares, 27, from Utah.

“You’re in the right place,” replied Schmidt. Manzanares took his place in the circle of about 20 people in a patch of grass.

Schmidt asked participants what they wanted to get out of the session.

“Hope,” said one woman.

“Empowerment,” said another.

“It’s OK to feel sadness, grief and despair,” Schmidt told the group. “We’ll aim to normalize those hard feelings.”

Manzanares explained that drought has hit his community hard. Springs that were once flowing are now dry. Hungry and thirsty cattle are ruining once pristine land by scrounging for nourishment wherever they can find it. “I feel like I’m in a state of mourning or grieving when I think about it,” he said.

Bill McKibben, a climate activist for over 30 years who runs the climate advocacy organization 350.org, said groups like Good Grief can be an effective way to deal with climate grief.

"We can’t just be individuals, we need to join together and be a movement," he said in an interview. "It makes you less grief-stricken. The best antidote to feeling powerless is activism. It doesn’t make you less sad, but adds hope, solidarity and love."

Even though the latest U.N. report was a "kick in the stomach" for him, he cautioned that those experiencing existential grief over climate change are not its main victims. “It’s poor communities with flimsy homes that are washing away,” he said.

Distraught Over Having Kids

Almost all of the young people interviewed for this article said they were struggling with the ethical implications of having children.

“I’m definitely not having kids,” said Marcela Mulholland, 21, a student at the University of Florida in Orlando and a participant in the Uplift session. “I don’t have hope that we will avoid climate catastrophe. The changes that need to happen aren’t happening.”

Jordan said she used to talk with her kids about becoming parents someday. “I’d say, ‘You’ll be such a good dad.’ Now, it feels wrong. They don’t talk about it anymore either,” she said.

Antonia Cereijido, 26, a radio producer in New York City, is conflicted. “If I did have kids, they would have the worst life ever,” she said. But an environmental scientist told her that raising a climate-conscious child could be better than not having a child. “That did wonders for my anxiety, hearing that from a scientist. So now I’m not sure.”

At Uplift, Manzanares, who was about to become a father, said having a baby gives him hope. “It’s the most positive affirmation I can make about the future,” he said. “We aren’t giving up. This is a multigenerational problem.”

Grieving in Silence

Even with all the evidence, it’s still difficult to seriously discuss mourning the climate.

“It’s culturally acceptable to talk about all kinds of anxieties, but not the climate,” said Van Susteren, the climate psychiatrist. “People need to talk about their grief. When you do nothing, it just gets worse.”

The Yale survey found that 65 percent of those surveyed discuss global warming “never” or “rarely.”

Jennifer Atkinson, a professor of environmental humanities at the University of Washington in Bothell, will teach her second course on climate grief next semester. She offers the course to students in the environmental studies program to help prevent the burnout that can develop by confronting the problem daily. “Some students say they’re going to change majors, design video games, 'this is too depressing,' ” she told NBC News.

When the course was first offered last spring, Atkinson and the school received support, but also a fair amount of ridicule.

“Do the students roll out nap mats and curl up in the fetal position with their blankies and pacifiers while listening to her lectures?” read a message sent to the school, she wrote in an opinion essay.

The inability to talk about the issues could be fueling increased rates of depression seen in young people, Van Susteren said.

“Think about it, do you always understand what is really bothering you deep down?” she said. “The constant barrage of news that the world is ending takes a toll.”

For some young people, the sadness is caused by inaction.

Cindy Chung, 17, of Bayonne, New Jersey, is an activist with iMatter, a network of high school students who advocate for environmental measures on a local level. She struggles to understand how people, especially adults, can continue with business as usual.

“It wasn’t our choice to be born into a doomed world,” she said. “All this terrible stuff can happen by 2030, and I won’t even be 30 years old. It’s so frightening.”