Wild mockingbirds distinguish among familiar humans (original) (raw)

Abstract

Although individuals of some species appear able to distinguish among individuals of a second species, an alternative explanation is that individuals of the first species may simply be distinguishing between familiar and unfamiliar individuals of the second species. In that case, they would not be learning unique characteristics of any given heterospecific, as commonly assumed. Here we show that female Northern Mockingbirds (Mimus polyglottos) can quickly learn to distinguish among different familiar humans, flushing sooner from their nest when approached by people who pose increasingly greater threats. These results demonstrate that a common small songbird has surprising cognitive abilities, which likely facilitated its widespread success in human-dominated habitats. More generally, urban wildlife may be more perceptive of differences among humans than previously imagined.

Subject terms: Urban ecology, Behavioural ecology

Introduction

A wide variety of arthropods and vertebrates can distinguish among individuals of their own species1–6. This ability is not surprising, as it facilitates mate selection, parental care, communication, and practically all other social interactions. Much less expected and explored is the emerging generalization that individuals of one species can distinguish among individuals of a different species. This ability is most apparent in domestic species such as farm animals and household pets7–11 and in vertebrates considered to have high cognitive function, such as corvids, primates and elephants12–14. Although most commonly studied with captive animals in highly controlled settings e.g., Refs.15,16, wild individuals in natural environments also appear able to distinguish among heterospecific individuals17–24. Yet, establishing the occurrence of “true” individual recognition is controversial, even among individuals of the same species25,26. At issue is whether the perceiving individual learns unique characteristics of the detected individual or simply distinguishes between familiar and unfamiliar individuals or groups of individuals. The challenge is especially great for documenting heterospecific individual recognition in natural settings.

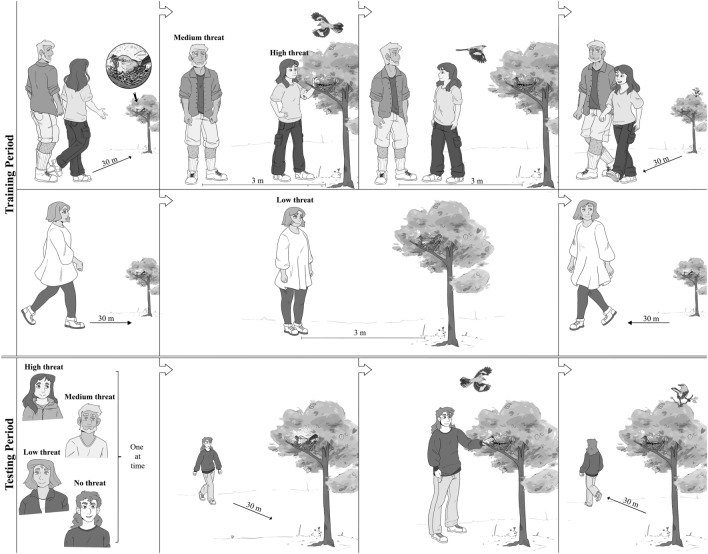

Here we describe an experimental study with Northern Mockingbirds (Mimus polyglottos), a common species in urban environments throughout the continental United States. We systematically exposed free-living birds to human intruders that varied in their degree of threat (Fig. 1). The goal was to test whether mockingbirds could distinguish among them, responding in a manner reflecting the degree of risk. We predicted that female mockingbirds would flush from their nest progressively sooner when approached by familiar humans who posed increasing levels of threat (No Threat, Low Threat, Medium Threat, and High Threat). Such a result would demonstrate the birds’ ability to learn unique cues of each human, to quickly process that information, and to respond in a manner specific and functionally relevant to a wide variety of familiar humans. It would reveal a new level of cognitive function in a small songbird (Passeriformes) and help explain mockingbirds’ ability to thrive in urban environments.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol. Training period, top row: High and Medium Threat individuals approached nest together. The Medium Threat individual stopped 3 m from nest, while the High Threat individual stood at nest for 15 s, placed hand on rim of nest for 15 s, and retreated to where the Medium Threat individual was standing. They faced each other for 15 s before retreating together along the same path. Training period, second row: Low Threat individual approached the nest along a different path and stood 3 m away for 10 min before retreating. The training period lasted 3 days, with one visit of each visitor type per day. Testing period, bottom row: High, Medium, Low and No (control) Threat individuals approached the nest a single time, separately, in random order, with at least 6 h between visits, over a 2-day period. In all approaches, we recorded the distance between the individual and the nest when the bird flushed (Flush Distance). Illustration: José Alejandro Riascos Ramírez.

Results

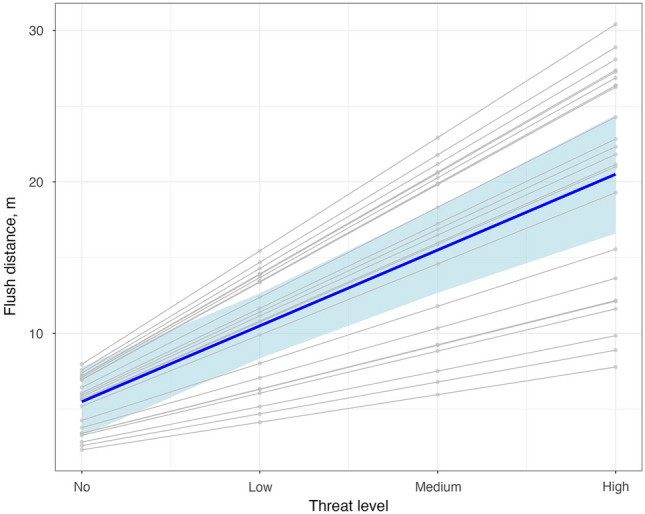

Experimental trials consisted of a 3-day training period, during which incubating females were exposed daily to one human of each threat category except for No Threat, and a 2-day testing period, during which we recorded their responses to a final approach of each human. Over the training period, flush distance increased ~ 2.5 m/day for High and Medium Threat individuals (LMM: t = 3.27, df = 72, p = 0.002) and birds did not noticeably respond to Low Threat individuals, demonstrating the effectiveness of those treatments. On test days, birds responded differently to approaches by the four humans; flush distance increased ~ 5 m for each increase in threat level (LMM: z = 7.10, p < 0.001, Fig. 2 & Supplementary Fig. S1). A varying slope model best fit the data, indicating high variation among individuals in sensitivity to humans of progressively higher threat levels. The model’s total explanatory power was high (conditional _R_2 = 0.61), with Threat Level alone explaining 31% of the variance (marginal R2). The number of attacks was unrelated to Threat Level (Poisson GLMM, varying intercept model: z = − 1.77, p = 0.077), with Threat Level alone explaining a very small extent of variance (marginal R2 = 0.005). Likewise, the number of alarm calls was not related to Threat Level (varying slope and intercept model; z = 1.54, p = 0.12).

Figure 2.

Incubating mockingbirds flush from their nest at greater distances when approached by familiar humans known by them to be more threatening. Blue line shows the average response and shading shows the 95% confidence intervals around the average. Gray lines show model fit for individual birds.

Discussion

These results demonstrate that mockingbirds can recognize multiple familiar humans individually. Prior studies on wild birds have been unable to rule out the possibility that study species were instead making coarse-level distinctions between familiar and unfamiliar humans18–23,27–29. The flush distances of mockingbirds were graded, proportional to the level of threat posed by each individual who approached the nest. This individual-specific receiver response requires the ability to distinguish among multiple types of heterospecific individuals and characterizes the strictest definition of individual recognition within species1,25,26; it has not previously been documented between species, except for a study involving only two types of familiar humans17. Remarkably, mockingbirds learned to identify humans and assess their threat levels in as little as three exposures of 30 s near the nest.

Understanding animals’ ability to distinguish among individuals of a different species is important for two reasons. First, it reflects cognitive ability because it requires integration of learning, recalling, and applying information30. Those processes are well-established in parrots and corvids, which are considered cognitively superior to other birds31–33. Other avian taxa remain largely overlooked and untested in ecologically relevant settings19,23. Our results add to the growing consensus that cognitive function is likely greater and more phylogenetically widespread in birds than generally recognized34,35.

Second, because practically all studies on individual recognition of heterospecifics have tested the ability of various animals to distinguish among people, results have direct relevance to human-wildlife interactions and urban ecology36,37. Specifically, they reveal the extent to which species become aware of and can respond to differences in human behavior. Given that humans are highly variable in their interactions with wildlife, the ability to distinguish quickly among individuals who pose different degrees of risk or gain would be highly beneficial and could partially explain which species are most likely to thrive in human-dominated environments38–43, but see Ref.23.

In addition to mockingbirds’ surprising cognitive function, another factor may facilitate their ability to learn quickly to discriminate among familiar humans22: consistent exposure to hundreds of non-threatening people could help them learn which human stimuli are consistently distinctive (e.g., facial features) and which are not (e.g., clothing)17. Then, when a particular human becomes a threat or benefactor, the birds are more able to quickly learn the person’s unique characteristics than if they had not previously watched so many humans.

We conclude that nesting mockingbirds are keenly aware of nearby humans as individuals, not just collectively. Daily, hundreds of students walked past the nests in this study and the birds ignored the vast majority. Yet, they responded quickly to a few individuals in a manner proportional to those individuals’ unique level of threat. If the underlying cognitive processes of this behavior occur in other taxa, individual differences in human behavior may play a large role in structuring communities of urban wildlife.

Methods

Our study took place in Gainesville, Florida on the ~ 800-ha campus of the University of Florida. Northern mockingbirds were chosen for study because they are common on campus and urban areas, frequently nest in isolated shrubs or small trees, and are known to distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar humans24. Furthermore, they are highly acclimated to the presence of humans, typically showing no response unless approached within 2–3 m. The average number of pedestrians passing within 5 m of nests over a 5 min period is 4.5 ± 6.424. Pairs are socially monogamous and territorial. Territory size is 1–2 ha on campus. Only the female incubates44, which allowed us to tightly control a given bird’s exposure to different humans. Because much of the population was individually color banded and the study occurred during a single breeding season on widely separated territories, we are confident that each female was included only once in our sample.

When the nest of an incubating female was discovered, we first established three 30 m paths along which an approaching human could be seen from the nest. In some cases, a person not participating in the trials removed a small number of leaves or twigs near the nest to assure equal visibility of approaching humans along all paths. The purpose of multiple approach paths was to minimize the possibility that the bird might respond to the direction of approach rather than (or in addition to) the identity of the human. For each nest, assignment of High, Medium, Low and No Threat individuals was randomized. Approach paths were randomly assigned, then sequentially rotated so that threat level could not be predicted by path location. The rate at which all individuals approached and retreated from nests was calibrated and standardized. We tested 24 incubating females during peak nesting period (May and June) in 2009. Trials on a given nest occurred over five consecutive days (2 trials per day), divided into a training period of 3 days and a testing period of 2 days.

Training period On the first 3 days of a trial, the nest was visited by a pair of High and Medium Threat individuals simultaneously, and at least 3 h before or after a visit by the Low Threat individual. The goal was to establish the three treatments—i.e., to familiarize the female with each type of human and their threat level. Prior work using a similar protocol established that mockingbirds significantly increase their response to threatening humans after 2 visits to a nest24. High Threat individuals approached the incubating female from 30 m at a rate of 1 m/s, maintaining eye contact with her, until they were ~ 1 m from the nest or she had flushed from the nest. They stood still for 15 s without making eye contact with her and then placed one hand on the rim of the nest for 15 s before retreating. The Medium Threat individual walked beside the High Threat individual but stopped 3 m from the nest and stood still, looking towards the nest while the High Threat individual proceeded to it. When the female flushed, neither individual looked at or responded to it. After leaving the nest, the High Threat individual walked back ~ 2 m and stood facing the Medium Threat individual within ~ 0.5 m for 15 s before both traveled together along the same path and at the same rate as they had approached. Low Threat individuals approached the incubating female along a different path at 1 m/s while maintaining eye contact with her, stopped 3 m away, stood quietly for 10 min without looking at her or the nest, and then retreated in the same manner as High Threat and Medium Threat individuals (except for path). The No Threat individual (Control) did not approach the nest during the training period, only once during the testing period. We recorded the approaching human’s distance from the nest when the female left the nest (Flush Distance), and the number of alarm calls and attacks. Alarm calls are distinctive—loud, of short duration and with a wide bandwidth. Attacks were defined as downward flights within 1 m of the intruder’s head. In rare cases, they resulted in direct contact (usually with the bird’s feet).

Testing period On the last 2 days of a trial, each incubating female was exposed to one individual of each threat level, including the No Threat individual who had not previously approached the nest. The order and paths of these approaches were randomized. Two trials occurred per day, separated by > 6 h. In these four trials, all humans behaved identically, except for the approach path used. They approached the nest from 30 m at a rate of 1 m/s, paused ~ 1 m from the nest for 15 s, touched the rim of the nest for 15 s, and walked away at the same rate and along the same path as they had arrived. None paused 3 m from the nest. We collected the same data as during the training period.

We emphasize that our experimental design did not employ distinctive clothing or masks with exaggerated features that the birds could associate with treatments. All participants wore what they normally would have worn if they had not been participating in a trial. The only restriction was that they could not wear hats or sunglasses. Except for the first author, all participants in trials were university students, presumably indistinguishable at the start of trials from the other ~ 50,000 students on campus at the time. Our goal was to mimic as closely as possible the natural variety of humans near each bird’s nest. Nine women and five men participated in the trials, all varying in complexion and stature.

Because all trials were conducted during the focal females’ incubation period, our experimental design also controlled for the well-known association between nest defense behavior and stage of the breeding cycle45. If any eggs hatched or disappeared, we discontinued trials on the impacted nest.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Specifically, we adhered to an experimental protocol that was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #D884-007) and that followed ARRIVE guidelines.

Statistical analyses

Using mixed models (LMM, GLMM) with the appropriate probability distribution, we assessed the effects of threat level, including it as a covariate, and bird individual, treating it as a random effect to account for repeated measures. We treated the threat levels as continuous and assumed they increased linearly from No Threat to High Threat. We compared three models with different random effect terms: (1) a varying intercept model with location as a random effect to account for individual variation in average level of response; (2) a varying slope model with visit as a random effect to account for individual variation in the response across threat levels; and (3) a varying intercept, varying slope model that accounted for both types of variation in response. We used the Likelihood Ratio Test to compare models.

For flush distance, a continuous response, we used linear mixed models (LMM). We evaluated the assumptions of homoscedasticity and normality of residuals by visually examining residual plots and QQ-plots of the residuals. For number of attacks and alarm calls, we used generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) with a Poisson distribution and log-link. We checked the assumption that the variance is equal to the mean (lack of overdispersion) and compared the predicted to observed counts through rootograms. Mixed models were run in the glmmTMB (version 1.1-28) package, and all statistical analysis were conducted in R version 4.1.2. We calculated a pseudo-R2 for mixed models using the trigamma function in the MuMIn package.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Julie Allen, Melissa Marie Allen, Jill Jankowski, Craig Littauer, Yanet Maderos, Daphna Shaw, Christine Stracey, Oona Takano, and other members of the Levey and Robinson labs for project feedback and help with field work. We thank José Alejandro Riascos Ramírez for preparation of Fig. 1. Funding was provided by the Katharine Ordway Fund for Ecosystem Conservation at the University of Florida and by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship to Jessica Oswald.

Author contributions

D.J.L., S.K.R. and G.A.L. designed the study. G.A.L. led the field work and was assisted by D.J.L., A.P.S., M.E.D. and J.A.O. J.R.P. analyzed the data. D.J.L. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and all authors participated in its revision.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Dryad repository, https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.p2ngf1vvq.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Douglas J. Levey, Email: dlevey@nsf.gov

Gustavo A. Londoño, Email: galondono@icesi.edu.co

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-36225-x.

References

- 1.Tibbetts EA, Dale J. Individual recognition: It is good to be different. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007;22:529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheehan MJ, Tibbetts EA. Specialized face learning is associated with individual recognition in paper wasps. Science. 2011;334:1272–1275. doi: 10.1126/science.1211334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung M, Wang MY, Huang ZY, Okuyama T. Diverse sensory cues for individual recognition. Dev. Growth Differ. 2020;62:507–515. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoddard PK, Beecher MD, Horning CL, Campbell SE. Recognition of individual neighbors by song in the song sparrow, a species with song repertoires. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1991;29:211–215. doi: 10.1007/Bf00166403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazial KA, Kenny TL, Burnett SC. Little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) recognize individual identity of conspecifics using sonar calls. Ethology. 2008;114:469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01483.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiley RH. Specificity and multiplicity in the recognition of individuals: Implications for the evolution of social behaviour. Biol. Rev. 2013;88:179–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huber L, Racca A, Scaf B, Viranyi Z, Range F. Discrimination of familiar human faces in dogs (Canis familiaris) Learn. Motiv. 2013;44:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nawroth C, et al. Farm animal cognition-linking behavior, welfare and ethics. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jardat P, Lansade L. Cognition and the human-animal relationship: a review of the sociocognitive skills of domestic mammals toward humans. Anim. Cogn. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10071-021-01557-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knolle F, Goncalves RP, Morton AJ. Sheep recognize familiar and unfamiliar human faces from two-dimensional images. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1098/rsos.171228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proops L, McComb K. Cross-modal individual recognition in domestic horses (Equus caballus) extends to familiar humans. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2012;279:3131–3138. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.0626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salmi R, Jones CE, Carrigan J. Who is there? Captive western gorillas distinguish human voices based on familiarity and nature of previous interactions. Anim. Cogn. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10071-021-01543-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller JJA, Massen JJM, Bugnyar T, Osvath M. Ravens remember the nature of a single reciprocal interaction sequence over 2 days and even after a month. Anim. Behav. 2017;128:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2017.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McComb K, Shannon G, Sayialel KN, Moss C. Elephants can determine ethnicity, gender, and age from acoustic cues in human voices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:5433–5438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321543111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vincze E, et al. Does urbanization facilitate individual recognition of humans by house sparrows? Anim. Cogn. 2015;18:291–298. doi: 10.1007/s10071-014-0799-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohrer KN, Ferkin MH. Meadow voles, Microtus pennsylvanicus, can discriminate between scents of individual house cats, Felis catus. Ethology. 2019;125:316–323. doi: 10.1111/eth.12856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belguermi A, et al. Pigeons discriminate between human feeders. Anim. Cogn. 2011;14:909–914. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marzluff JM, Walls J, Cornell HN, Withey JC, Craig DP. Lasting recognition of threatening people by wild American crows. Anim. Behav. 2010;79:699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.12.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnett C, et al. The ability of North Island robins to discriminate between humans is related to their behavioural type. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutour M, Walsh SL, Speechley EM, Ridley AR. Female Western Australian magpies discriminate between familiar and unfamiliar human voices. Ethology. 2021;127:979–985. doi: 10.1111/eth.13218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee VE, Regli N, McIvor GE, Thornton A. Social learning about dangerous people by wild jackdaws. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1098/rsos.191031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee WY, Lee SI, Choe JC, Jablonski PG. Wild birds recognize individual humans: Experiments on magpies, Pica pica. Anim. Cogn. 2011;14:817–825. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee WY, et al. Antarctic skuas recognize individual humans. Anim. Cogn. 2016;19:861–865. doi: 10.1007/s10071-016-0970-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levey DJ, et al. Urban mockingbirds quickly learn to identify individual humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:8959–8962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811422106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steiger S, Muller JK. 'True' and 'untrue' individual recognition: Suggestion of a less restrictive definition. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008;23:355–355. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tibbetts EA, Sheehan MJ, Dale J. A testable definition of individual recognition. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008;23:356–356. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornell HN, Marzluff JM, Pecoraro S. Social learning spreads knowledge about dangerous humans among American crows. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2012;279:499–508. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson GL, Clayton NS, Thornton A. Wild jackdaws, Corvus monedula, recognize individual humans and may respond to gaze direction with defensive behaviour. Anim. Behav. 2015;108:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng CZ, Liang W. Living together: Waterbirds distinguish between local fishermen and casual outfits. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e00994. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shettleworth, S. J. Cognition, Evolution, and Behavior, 2nd ed. (Oxford University Press, 2010).

- 31.Pika S, Sima MJ, Blum CR, Herrmann E, Mundry R. Ravens parallel great apes in physical and social cognitive skills. Sci. Rep.-UK. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77060-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambert ML, Jacobs I, Osvath M, von Bayern AMP. Birds of a feather? Parrot and corvid cognition compared. Behaviour. 2019;156:505–594. doi: 10.1163/1568539x-00003527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emery NJ. Cognitive ornithology: The evolution of avian intelligence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2006;361:23–43. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ackerman, J. & Burgoyne, J. The Genius of Birds (Penguin Press, 2016).

- 35.Emery, N. & Waal, F. B. M. D. Bird Brain: An Exploration of Avian Intelligence (Princeton University Press, 2016).

- 36.Goumas M, Lee VE, Boogert NJ, Kelley LA, Thornton A. The role of animal cognition in human–wildlife interactions. Front. Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.589978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levey DJ, Benkman CW. Fruit-seed disperser interactions: Timely insights from a long-term perspective. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999;14:41–43. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vincze E, et al. Consistency and plasticity of risk-taking behaviour towards humans at the nest in urban and forest great tits, Parus major. Anim. Behav. 2021;179:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2021.06.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sol D, Lapiedra O, Gonzalez-Lagos C. Behavioural adjustments for a life in the city. Anim. Behav. 2013;85:1101–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moller AP. Flight distance of urban birds, predation, and selection for urban life. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2008;63:63–75. doi: 10.1007/s00265-008-0636-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chow PKY, Clayton NS, Steele MA. Cognitive performance of wild eastern gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) in rural and urban, native, and non-native environments. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.615899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barrett LP, Stanton LA, Benson-Amram S. The cognition of 'nuisance' species. Anim. Behav. 2019;147:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2018.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee VE, Thornton A. Animal cognition in an urbanised world. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.633947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farnsworth, G., Londoño, G. A., Martin, J. U., Derrickson, K. C. & Breitwisch, R. In Birds of the World (ed. Poole, A. F.) (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2020).

- 45.Knight RL, Temple SA. Why does intensity of avian nest defense increase during the nesting cycle? Auk. 1986;103:318–327. doi: 10.1093/auk/103.2.318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the Dryad repository, https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.p2ngf1vvq.