Snakebite envenoming in Africa remains widely neglected and demands multidisciplinary attention (original) (raw)

Snakebite envenoming can cause morbidity, permanent disability or death but treatment and prevention thereof remains highly inadequate in Africa. Overcoming structural and financial barriers that impede existing initiatives to improve medical management and mitigate human-snake conflict is urgently needed.

Subject terms: Public health, Disease prevention, Herpetology, Funding

Snakebite envenoming causes a significant public health burden in Africa. In this Comment, the authors describe the limitations of current snakebite control measures and emphasise the need for more funding to reduce future harm.

Africa accommodates over 130 venomous snake species1 that cause over 500,000 human envenomations and approximately 30,000 deaths each year2. However, these numbers are underestimated because many patients are not admitted to hospitals and epidemiological data is lacking or sparse for most of Africa. Findings from household surveys suggest that about 80% of snakebite victims seek help from traditional healers exclusively or receive no treatment at all3,4. The risk of snakebite disproportionally affects low-income populations5,6 and children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable due to a disadvantageous body mass-to-venom ratio. The importance of snakebite as a public health issue was emphasised by the recognition as a neglected tropical disease (NTD) by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017. In addition, the snakebite crisis is linked to several of the United Nations sustainable development goals (SDG), such as ending poverty, reducing inequalities, and ensuring quality education, which are crucial elements on the way to reduce the impact of snakebite. This, on the other hand, will be a requirement to achieve the goals of good health and productive employment and economic development. However, resultant activities such as intensified research into epidemiology, clinical management, and snake ecology as well as activities to increase preventive measures are still very limited.

Current public health measures are inadequate

A key factor of snakebite-related morbidity and mortality in Africa is poverty and unequal access to safe and effective medical care. Snakebite envenoming is rarely fatal if appropriately managed. However, poorly equipped clinics in rural areas and inadequate training in snakebite management for medical professionals negatively affect treatment outcomes following snakebite. Public healthcare infrastructure and workforce is chronically underfunded in most African countries7,8 and structural and financial barriers impede health-related research9, which is much needed with regard to snakebite. Surveys revealed that the utilisation of unproven traditional remedies is common and the practice base as well as expertise of health care workers is low in many health facilities10,11. In addition, late treatment is a common feature after African snakebite incidences and hospital admission delays frequently exceed 24 h, amplifying the risk for disabling or life-threatening complications12. An underrepresentation in registration of patients bitten by neurotoxic species in hospital admissions13 might be a direct consequence of such delays as these venoms can result in rapid respiratory failure. Case reports demonstrate that even envenoming by snakes considered less toxic can cause death before patients arrive at a clinic14. Once a health facility is reached, treatment options are often suboptimal with essential medicines such as antivenom lacking15.

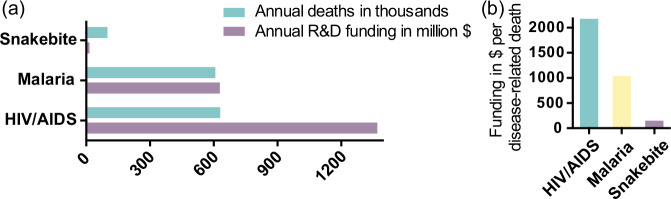

Lack of funding remains a major bottleneck limiting snakebite treatment, mitigating activities, and research in Africa. Snakebite therapy with effective antivenom is the only disease-modifying treatment option available and highly cost-effective16. However, a product effective against several medically important species (Fav-Afrique) was unprofitable and discontinued in 2014 and recent production problems at the only antivenom manufacturer in sub-Saharan Africa (South African Vaccine Producers) have led to a critical shortage of anti-venom since 2022. In addition, the quality, efficacy, and safety of existing products are often insufficiently characterised17 and the absence of effective antivenom against some dangerous species18 requires attention. Thus, developing novel treatments19 or repurposing drugs to inhibit snake toxins20 are important goals. Despite the urgency, progress is slow and funding for drug development remains negligible nonetheless, particularly when compared to other diseases (Fig. 1). This imbalance is even larger when considering the lack of funding for snakebite treatment and prevention. While substantial funds are allocated to HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention programmes in low- and middle-income countries (US$ 20.8 billion in 2022)21, in the case of snakebite envenoming nearly all funding is dedicated towards drug research and development. However, novel medicines will not solve the neglected crisis of snakebite victims not receiving antivenom due to insufficient funds, manufacturing and/or distribution problems within health systems. Even the most effective therapy can benefit patients in need only if timely accessible. In addition to detrimental clinical consequences, failure to provide existing antivenom to those in need may also distort the true demand and market for these products and can sabotage attempts to improve community and medical education if effective treatment modalities are simply not accessible in clinics.

Fig. 1. Imbalance of public health burden und funding.

Research and development (R&D) investment for snakebite is still negligible in absolute numbers (a) and relative to the disease burden (b) in comparison to other diseases of concern in sub-Saharan Africa although causing >100,000 human fatalities each year. Sources: WHO 2022, Global Observatory on Health Research and Development; UNAIDS; Gutiérrez et al.2.

Lack of knowledge, misconceptions, and superstition about snakes and snakebite are widespread and potentially dangerous as they can affect snakebite risk and treatment seeking behaviour. Education is an effective means to reduce human-snake conflict and snakebite risk22 and was postulated as a key activity to empower communities to achieve sustained prevention and control of snakebite23. However, access to accurate information about snakes and snakebite that is readily understandable remains limited, especially in rural areas. Furthermore, low literacy levels and/or the presence of multiple local languages may represent additional barriers in several regions. Existing activities to reduce human-snake conflict, improve snakebite management, and snake education are primarily run by private initiatives or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with little or no funding and can be complicated by structural barriers and bureaucracy, restraining their reach, capabilities, and sustainability.

Harm caused by snakebite is preventable if action is taken

To address the core of the snakebite crisis, it should be acknowledged that inequality, not science, is the primary problem. The WHO aim to halve the global impact of snakebite by 203023 requires broad political willingness and commitment to address snakebite-related health disparities in the form of resource allocations and investments. Local financing is needed and several low-cost interventions can be helpful and demonstrate that the issue is taken seriously, such as classifying snakebite as a notifiable disease, implementing a venom information helpline and adding the topic to school and medical education curricula. Global health funders could make a significant difference by allocating resources to snakebite-related activities. To achieve the necessary commitment, increased attention outside the scientific community and engagement with funders, key opinion leaders, and policy-makers is needed. Connecting individual initiatives, a more organised approach and promoting intersectoral collaboration may be helpful to create synergies. The narrative of snakebite-related death or disability as an unfortunate, unavoidable fate must be changed with the help of communication experts. Public awareness of the devastating consequences for individuals and society as well as the availability of countermeasures may increase political pressure to act. As snakebite is preventable and treatable, establishing snakebite as a healthcare priority locally and globally could make the WHO aim achievable.

Preventive measures play a crucial role in reducing the impact of many diseases and are underutilised in relation to envenomation by snakes. Interventions aiming to increase health literacy in rural and poor communities represent a strategy to mitigate impacts of health disparities24 and are urgently needed in the context of snakebite. The risk of being bitten is influenced by snake and mainly human behaviours. Thus, public awareness and education interventions have the potential to decrease the health burden caused by snakebite similar to how preventive immunisation reduces the risks of certain infectious diseases. In many countries, snake enthusiasts are involved in snake relocations from human-snake conflict situations25 or perform outreach. Educational activities occur in person and online with social media playing an increasing role as a source of public health information and misinformation26. At the time of writing, 25 Facebook communities dedicated to African snakes were followed by more than 1 million users. To be effective, the choice of interventions has to be adapted depending on the setting and target population. Strategies to reach rural communities, which may not have internet access, and to incorporate their expectations and needs are essential. The feasibility of large-scale measures will benefit from building upon pre-existing snakebite awareness and educational activities and utilising experiences made in this context. Collaborations between local snake experts and private initiatives that already operate such activities with public institutions could develop age and context appropriate educational materials on venomous snakes and snakebite for school and community education in a timely manner. Funding bodies often require that interventions are evidence based, measureable, and come with a cost-effectiveness-analysis. So far, little evidence has been generated on preventive interventions27. However, uncertainty does not preclude health benefits, in particular in understudied areas of unmet medical need, and global health funding should not be limited to measureable and predictable interventions28. For some simple messages there is a reasonable logic to assume a benefit in real-life settings (e.g., keep your surroundings clean, use a light when walking at night, wear closed shoes and trousers in bushy areas). Sensitisation for these potentially life-saving activities should not be delayed.

Every snakebite is a medical emergency and should be managed accordingly29. Access to treatment is time-critical and institutionalising this concept is crucial for the outcome of snakebite victims. Interventions that aim to accelerate hospital admission and referral may differ depending on the country and local conditions. An example may be immediate transport of patients to sufficiently equipped clinics30. Moreover, funding and regulatory and logistical support is required to ensure that effective antivenom and other treatment modalities can be utilised for snakebite management. The use of drones (unmanned aerial vehicles) has the potential to deliver emergency medical services in remote areas31, which could facilitate rapid access to antivenom in some areas but comes at a cost. Increased stability of lyophilised antivenom could solve distribution challenges of liquid antivenom in areas without cold-chain infrastructure. Based on past and current limitations, suggestions have been made on how the availability and accessibility of antivenom could be improved across the African continent32. Finally, training of healthcare professionals and incorporating snakebite management into the national health curricula of African countries are crucial to ensure timely and correct diagnosis and safe and effective treatment, including antivenom administration when necessary and knowledge about key supportive care. Remote specialist consultation via phone or internet may help to bridge expertise gaps in patient management but requires reliable infrastructure and integration in clinical practice. In the absence of effective antivenom, symptomatic treatment modalities, including assisted ventilation, dialysis, adequate wound care, and safe blood for transfusion as well as diagnostic capabilities, are of great significance to improve patient outcomes. Access to these treatment modalities must be increased in suspected snakebite hotspots.

Conclusion

To achieve a significant reduction of mortality and disability as targeted by the WHO, parallel interventions appear essential that complement each other and can have additive effects: educating communities about snakebite prevention and safe and effective first aid, training of medical professionals in snakebite management, improving the availability of antivenom and other treatment modalities without delay, and institutionalising the concept that every snakebite is a medical emergency, requiring immediate hospital admission and referral of snakebite victims to ensure timely treatment.

The designation of snakebite as a NTD has stimulated increased scientific interest in this hidden health crisis but both attention and funding are still grossly inadequate in view of the high morbidity and mortality numbers caused by snakebites, which are in fact preventable to a large extent. The allocation of resources from both public and private funding bodies is a prerequisite for these much-needed interventions and necessitates attention outside the scientific community and intersectoral collaboration to promote transformative change. Snakebite does not need to remain a neglected disease.

Author contributions

P.B., F.T., M.v.D., E.L.S., and L.B.M. jointly conceptualised the paper. P.B. wrote the first draft of the manuscript with critical input, additions, and editing from F.T., M.v.D., E.L.S., and L.B.M.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Spawls, S. & Branch, B. The dangerous snakes of Africa, (Princeton University Press, 2020).

- 2.Gutiérrez, J. M. et al. Snakebite envenoming. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.3, 17063 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farooq, H. et al. Snakebite incidence in rural sub-Saharan Africa might be severely underestimated. Toxicon219, 106932 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hakizimana Id, D. et al. Snakebite incidence and healthcare-seeking behaviors in Eastern Province, Rwanda: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.18, e0012378 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison, R. A., Hargreaves, A., Wagstaff, S. C., Faragher, B. & Lalloo, D. G. Snake envenoming: a disease of poverty. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.3, e569 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Snakebite envenoming: a strategy for prevention and control. (2019). https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/324838 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Oleribe, O. O. et al. Identifying key challenges facing healthcare systems in Africa and potential solutions. Int. J. Gen. Med.12, 395–403 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmat, A. et al. The health workforce status in the WHO African Region: findings of a cross-sectional study. BMJ Glob. Heal.7, e008317 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conradie, A., Duys, R., Forget, P. & Biccard, B. M. Barriers to clinical research in Africa: a quantitative and qualitative survey of clinical researchers in 27 African countries. Br. J. Anaesth.121, 813–821 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michael, G. C. et al. Knowledge of venomous snakes, snakebite first aid, treatment, and prevention among clinicians in northern Nigeria: A cross-sectional multicentre study. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg.112, 47–56 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ameade, E. P. K., Bonney, I. & Boateng, E. T. Health professionals’ overestimation of knowledge on snakebite management, a threat to the survival of snakebite victims—a cross-sectional study in Ghana. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.15, e0008756 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chippaux, J. P. Snakebite in Africa: current situation and urgent needs. in Handbook of Venoms and Toxins of Reptiles 593–612 10.1201/9781420008661-30 (2021).

- 13.Potet, J. et al. Snakebite envenoming at MSF: a decade of clinical challenges and antivenom access issues. Toxicon X17, 100146 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theart, F., Kemp, L., Buys, C., Hauptfleisch, M. & Berg, P. A confirmed human fatality due to envenomation by the Kunene Coral Snake (Aspidelaps lubricus cowlesi) in Namibia. Toxicon237, 107537 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mavoungou, L. B., Jackson, K. & Goma-Tchimbakala, J. Prevalence and therapeutic management of snakebite cases in the health facilities of the Bouenza department from 2009 to 2021, Republic of Congo. Pan Afr. Med. J.42, 139 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habib, A. G. & Brown, N. I. The snakebite problem and antivenom crisis from a health-economic perspective. Toxicon150, 115–123 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potet, J., Smith, J. & McIver, L. Reviewing evidence of the clinical effectiveness of commercially available antivenoms in sub-saharan africa identifies the need for a multi-centre, multi-antivenom clinical trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.13, e0007551 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saaiman, E. L. & Buys, P. J. C. Spitting cobra (Naja nigricincta nigricincta) bites complicated by rhabdomyolysis, possible intravascular haemolysis, and coagulopathy. South African Med. J.109, 736–740 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalek, I. S. et al. Synthetic development of a broadly neutralizing antibody against snake venom long-chain α-neurotoxins. Sci. Transl. Med.16, eadk1867 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albulescu, L. O. et al. A therapeutic combination of two small molecule toxin inhibitors provides broad preclinical efficacy against viper snakebite. Nat. Commun.11, 6094 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNAIDS. The path that ends AIDS: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2023. (2023). https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2023/global-aids-update-2023

- 22.Vaiyapuri, S. et al. Multifaceted community health education programs as powerful tools to mitigate snakebite-induced deaths, disabilities, and socioeconomic burden. Toxicon X17, 100147 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams, D. J. et al. Strategy for a globally coordinated response to a priority neglected tropical disease: snakebite envenoming. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.13, e0007059 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nutbeam, D. & Lloyd, J. E. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health42, 159–173 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hauptfleisch, M. L., Sikongo, I. N. & Theart, F. A spatial and temporal assessment of human-snake encounters in urban and peri-urban areas of Windhoek, Namibia. Urban Ecosyst.24, 165–173 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart, R., Madonsela, A., Tshabalala, N., Etale, L. & Theunissen, N. The importance of social media users’ responses in tackling digital COVID-19 misinformation in Africa. Digit. Heal.8, 20552076221085070 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chappuis, F., Sharma, S. K., Jha, N., Loutan, L. & Bovier, P. A. Protection against snake bites by sleeping under a bed net in Southeastern Nepal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg.77, 197–199 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierson, L. & Verguet, S. When should global health actors prioritise more uncertain interventions? Lancet Glob. Health11, e615–e622 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warrell, D. A. & Williams, D. J. Clinical aspects of snakebite envenoming and its treatment in low-resource settings. Lancet401, 1382–1398 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma, S. K. et al. Effectiveness of rapid transport of victims and community health education on snake bite fatalities in rural nepal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg.89, 145–150 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nisingizwe, M. P. et al. Effect of unmanned aerial vehicle (drone) delivery on blood product delivery time and wastage in Rwanda: a retrospective, cross-sectional study and time series analysis. Lancet Glob. Heal.10, e564–e569 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalhat, M. M. et al. Availability, accessibility and use of antivenom for snakebite envenomation in Africa with proposed strategies to overcome the limitations. Toxicon X18, 100152 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]