Off pump coronary artery bypass surgery for significant left ventricular dysfunction: safety, feasibility, and trends in methodology over time—an early experience (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objective

To examine the safety and applicability of off pump coronary artery bypass surgery (OPCAB) in patients with significant left ventricular dysfunction and to discuss the clinical implications for the surgical methods.

Design

Retrospective study.

Setting

Tertiary care university affiliated referral centre.

Participants

353 consecutive patients with preoperative left ventricular ejection fraction ⩽ 35% who underwent coronary artery bypass over a three year period.

Main outcome measures

Postoperative morbidity and mortality.

Methods

144 patients operated by OPCAB were compared with 209 patients operated by conventional coronary artery bypass. Multivariate and univariate analyses were performed on the pre‐ and postoperative variables to predict risk factors associated with hospital morbidity and mortality.

Results

Patients in the OPCAB group were more likely to be women and to have congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and diabetes; patients in the on pump group were more likely to have had a recent myocardial infarction and to have more severe angina pectoris and an urgent/emergent status. The groups did not differ significantly in length of stay, major postoperative complication rates, or mortality. Comparison of the impact of the procedures on surgical methods over time showed an increase in the use of OPCAB (13% to 67%), without any impact on morbidity or mortality.

Conclusions

OPCAB is feasible and applicable for patients with depressed left ventricular function. This high risk group can potentially benefit from the off pump approach.

Keywords: low ejection fraction, off pump coronary artery bypass grafting, early experience

Despite modern advances in technology, myocardial protection, and postoperative care, left ventricular dysfunction remains an essential prognostic factor in coronary artery surgery.1,2

Off pump coronary artery bypass surgery (OPCAB) has theoretical and practical advantages over conventional coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). The patients best suited for this procedure have not yet been clearly defined, although some studies show that high risk patients would probably gain the most benefit from avoiding cardiopulmonary bypass.3,4,5,6 The objective of this retrospective study was to examine the safety and applicability of OPCAB in patients with significant left ventricular dysfunction and to discuss the clinical implications for the surgical methods.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Clinical data collection

The computerised records of 353 patients with an ejection fraction of ⩽ 35% who underwent CABG at Crawford Long‐Emory Hospital between 1 January 1999 and 31 December 2001 were reviewed. OPCAB was used for 144 patients and conventional CABG for 209.

The specific surgical procedure was selected non‐randomly by the surgeons on the basis of their experience and preference.

Operative technique

General anaesthesia was induced according to the institutional protocol (see appendix). A Swan‐Ganz catheter and transoesophageal echocardiography were used for additional monitoring.

In the OPCAB procedures, normothermia was maintained with warm intravenous fluids, a heating mattress, and a warm operating theatre. A standby perfusionist was available in all cases. The operation was performed through a median sternotomy. After conduit harvesting, heparin was given in doses of 1.5–3 mg/kg, depending on the individual surgeon's protocol, to achieve an activated clotting time of ⩾ 300 seconds. Values were checked every 30 minutes and heparin was added, if necessary. The pericardium was opened widely and the right pleura was opened to facilitate changes in the heart position without significant haemodynamic changes. Epiaortic ultrasound was performed in every patient. Deep pericardial traction stitches were used according to the surgeon's preference. Stabilisation was achieved with a suction device (Octopus 3/4 and Starfish 1 or 2; Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). Coronary shunts were not used routinely. Heparin was reversed with 75 mg protamine to achieve an activated clotting time of ⩾ 140 seconds.

In the conventional CABG procedures, anticoagulation was achieved with 3–4 mg/kg heparin to reach and maintain an activated clotting time of > 400 seconds. Cardiopulmonary bypass was instituted through a single right atrial cannula and an ascending aorta cannula. Standard cardiopulmonary bypass management included a membranous oxygenator, arterial line filters, non‐pulsatile flow, and mean arterial pressure above 60 mm Hg. The myocardium was protected with antegrade and retrograde cold blood cardioplegia and mild systemic hypothermia. Epiaortic ultrasound was performed in every patient. At the end of surgery, heparin was reversed with protamine.

Statistical analysis

Numerical variables are presented as mean (SD). Student's t test was used to compare categorical parameters and χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare patient characteristics and postoperative complications. A probability value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarises the patients' demographic characteristics and preoperative clinical data. The patients in the OPCAB group were more likely to be women and to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. Patients undergoing conventional CABG had more recent myocardial infarctions and tended to have more severe angina pectoris (Canadian Cardiovascular Society class III/IV).

Table 1 Preoperative characteristics.

| Variable | Off pump (n = 144) | On pump (n = 209) | Odds ratio | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63 (10.6) | 61.9 (10.9) | NA | 0.215 |

| Women | 40 (28%) | 36 (175%) | 1.8 | 0.024 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29 (5.4) | 29 (5.7) | NA | 0.892 |

| Congestive heart failure | 69 (48%) | 84 (40%) | 1.36 | 0.156 |

| CCS class III and IV | 53 (37%) | 103 (49%) | 0.467 | 0.022 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 28 (7) | 27.8 (6.3) | NA | 0.982 |

| Preoperative atrial fibrillation | 20 (14%) | 38 (18%) | 0.72 | 0.309 |

| Hypertension | 109 (75%) | 143 (68%) | 1.43 | 0.151 |

| Diabetes | 67 (46%) | 80 (38%) | 1.40 | 0.015 |

| Insulin dependent | 17 (12%) | 22 (10%) | 1.13 | 0.731 |

| Family history | 66 (46%) | 115 (55%) | 0.693 | 0.104 |

| COPD | 58 (40%) | 48 (23%) | 2.26 | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 19 (13%) | 26 (12%) | 1.07 | 0.871 |

| Dialysis dependent | 4 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 3.1 | 0.230 |

| Current smoker | 55 (38%) | 73 (35%) | 0.81 | 0.573 |

| Prior cardiovascular accident | 11 (7%) | 18 (8%) | 0.872 | 0.844 |

| Prior cardiac enlargement | 10 (7%) | 8 (4%) | 1.89 | 0.222 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 106 (73%) | 162 (77%) | 0.808 | 0.447 |

| < 24 hours | 10 (7%) | 28 (13%) | 0.480 | 0.056 |

| 1–7 days | 38 (26%) | 69 (33%) | 0.727 | 0.196 |

| Diseased vessels | ||||

| One | 13 (95%) | 11 (55%) | 1.8 | 0.198 |

| Two | 24 (165%) | 43 (20%) | 0.772 | 0.48 |

| Three | 107 (74%) | 155 (74%) | 1.00 | 1 |

| Status | ||||

| Elective | 136 (94%) | 181 (87%) | 2.63 | 0.019 |

| Urgent | 6 (4%) | 12 (6%) | 0.716 | 0.625 |

| Emergent or emergent/salvage | 2 (1%) | 16 (7%) | 0.170 | 0.011 |

| All repeat | 8 (5%) | 27 (13%) | 0.391 | 0.028 |

| Length of stay (days) | ||||

| Admission to surgery | 2.9 (2.9) | 2.8 (2.6) | NA | 0.753 |

| Surgery to discharge | 7.4 (7.3) | 8.3 (8.6) | NA | 0.272 |

| Total length of stay | 10.3 (7.9) | 11.1 (9.2) | NA | 0.374 |

Mean (SD) ejection fraction was 28 (7)% in the OPCAB group and 28 (6)% in the conventional (on pump) CABG group. This difference was not significant.

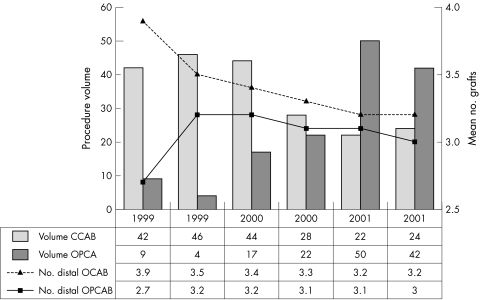

Figure 1 shows the number of distal anastomoses made and the trends in the surgical methods over time applied to patients with left ventricular dysfunction. The application of OPCAB to patients with low ejection fraction increased from 13% in 1999 to 67% in 2001.

Figure 1 Trends in off pump coronary artery bypass surgery (OPCAB) volume and revascularisation among patients with compromised left ventricular function. CCAB, conventional coronary artery bypass.

The statistical difference in the number of distal anastomoses between the two groups was eliminated as experience with OPCAB and the level of confidence increased.

Table 2 summarises postoperative complications, extubation time, and the length of stay. The groups did not differ statistically in early or late mortality or major complications. Mean (SD) duration of follow up for the OPCAB group was 160 (229) days with median of 67.5 days and for the conventional CABG group was 328 (498) days with a median of 101 days.

Table 2 Postoperative events.

| Variable | Off pump (n = 144) | On pump (n = 209) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ventilation time (hours) | 12.9 (27) | 25 (78) | 0.035 |

| Reintubated | 5 (3%) | 13 (6%) | 0.042 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 2.9 (5.9) | 3.6 (7.4) | 0.312 |

| Reoperative bleeding | 4 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 0.230 |

| Cardiovascular accident | 2 (1.4%) | 2 (1%) | 1 |

| Postoperative MI | 0 | 2 (1%) | 0.515 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1 (<1%) | 9 (4%) | 0.052 |

| New atrial fibrillation | 4 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 0.230 |

| Deep surgical wound infection | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) | 1 |

| New renal failure | 3 (2%) | 11 (5%) | 0.169 |

| New dialysis | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0.407 |

| Status at discharge (death) | 5 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 0.494 |

| Follow up (death) | 12 (8.3%) | 16 (7.7%) | 0.0524 |

The OPCAB patients were more likely to undergo extubation earlier and had a lower tendency to develop new renal failure and gastrointestinal bleeding, resulting in less time spent in the intensive care unit. However, these findings did not reach significance.

DISCUSSION

Improvements in myocardial preservation, monitoring, and postoperative care have made CABG much safer than before.7 Although success rates have risen for patients with left ventricular dysfunction, this population also has a wide variety of co‐morbid illnesses, as noted also in the present series, which may complicate surgery and have a detrimental effect on outcome. Furthermore, cardiopulmonary bypass has several well recognised practical disadvantages, especially the risk of myocardial injury and systemic inflammatory response, which can lead to multiorgan failure and a need for blood transfusions.8,9,10,11

In contrast to the global ischaemia caused by CABG with cross clamping and cardioplegic arrest, OPCAB causes only regional ischaemia. This may explain its apparent myocardial protective effect as indicated by the low incidence of myocardial infarction and enzyme leakage associated with this procedure.3,4,5,6,12 This advantage translates into greater haemodynamic stability, less postoperative low cardiac output syndrome, and shorter intensive care unit stay. Further support is provided by the present finding of a similar clinical outcome in the two groups, even though the OPCAB group had more co‐morbid illnesses.

An early, potential drawback of the OPCAB is the fewer distal anastomoses performed for each patient, which can mean incomplete revascularisation,4,13 with a possible negative impact on surgical outcome.14 We, too, noted a significant difference in this factor between the on pump CABG and OPCAB groups. However, further analysis over time indicated that the difference was related to the learning curve and was almost completely eliminated as surgeons gained experience with the technique. Indeed, the most recent studies report no statistical difference in the number of distal anastomoses between patients undergoing CABG and those undergoing OPCAB.15,16

The low incidence of neurological events among patients after both on pump and off pump bypass in our series may be attributable to our consistent use of epiaortic ultrasound to evaluate the ascending aorta. In the presence of a finding of high grade disease in the ascending aorta, the operative technique was changed accordingly.

For OPCAB to be considered feasible for high risk patients, its durability, effectiveness, and safety need to be at least equal to those of conventional CABG. Our data, together with recent reports, show that OPCAB meets these criteria and potentially benefits patients with left ventricular dysfunction.4,5,15,17,18,19 Furthermore, as opposed to previous reports in which the OPCAB mortality was lower than in the conventional CABG group, suggesting inherited bias, we noted a similar low mortality between the two groups.17,18,19 This may reflect the balanced, strict, and comprehensive institutional approach to this group of patients.

Others have reported that OPCAB has an important cost saving potential as well.20

Our study is limited by its retrospective, non‐randomised design. However, no results of prospective randomised studies on OPCAB versus conventional CABG for high risk patients have been published. We have found our data valuable, and our initial good results with this procedure have led to a growing trend in its use at our centre, especially for high risk patients.

Appendix

ANAESTHESIA PROTOCOL

1) Induction of anaesthesia

- Fentanyl 8 μg/kg

- Propofol 0.5–2.0 mg/kg

- Pancuronium 0.1 mg/kg

- Isoflurane to achieve bispectral index of < 40

- Blood pressure support with phenylephrine or other appropriate vasoactive drug as necessary

- Intubation when bispectral index is < 40 and adequate neuromuscular relaxation achieved.

2) Maintenance of anaesthesia

- Fentanyl infusion at 1.2 μg/kg/h

- Isoflurane to maintain bispectral index between 40 and 60

- No additional muscle relaxant

- No additional midazolam.

References

- 1.Roques F, Nashef S A, Michel P.et al Risk factors and outcome in European cardiac surgery: analysis of the European SCORE multinational database of 19030 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 199915816–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Multicenter Postinfarction Research Group Risk stratification and survival after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1983309331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bittner H B, Savitt M A, McKeown P P.et al Off pump coronary artery bypass grafting: excellent results in a group of selected high risk patients. J Cardiovasc Surg 200142451–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleveland J C, Jr, Shroyer A L, Chen A Y.et al Off‐pump coronary artery bypass grafting decreases risk‐adjusted mortality and morbidity. Ann Thorac Surg 2001721282–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chamberlain M H, Ascione R, Reeves B C.et al Evaluation of the effectiveness of off‐pump coronary artery bypass grafting in high risk patients: an observational study. Ann Thorac Surg 2002731866–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arom K V, Flavin T F, Emery R W.et al Is low ejection fraction safe for off pump coronary artery operation? Ann Thorac Surg 2000701021–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones E L, Weintraub W S, Craver J M.et al Coronary bypass surgery: is the operation different today? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991101108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ascione R, Lloyd C T, Gomes W J.et al Beating versus arrested heart revascularization: evaluation of myocardial function in prospective randomized study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 199915685–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallely M, Bannon P, Kritharides L. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome and off pump cardiac surgery. Heart Surg Forum 20014S7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokoyama T, Baumgartner F, Gheissari A.et al Off pump versus on pump coronary bypass in high risk subgroups. Ann Thorac Surg 2000701546–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cratier R, Brann S, Dagenais F.et al Systematic off pump coronary artery revascularization in multivessel disease: experience of three hundred cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000119221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calafiore A, Di Mauro M, Contini M.et al Myocardial revascularization with and without cardiopulmonary bypass in multivessel disease: impact of strategy on early outcome. Ann Thorac Surg 200172456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alkpinar B, Guden M, Sanisoglu I.et al Does off pump coronary artery bypass surgery reduce mortality in high risk patients? Heart Surg Forum 20014231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones E L, Wientroub W S. The importance of complete revascularization during long term follow up after coronary artery operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996112227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al‐Ruzzeh S, Nakamura K, Athanasiou T.et al Does off pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) surgery improve the outcome in high risk patients? A comparative study of 1398 high risk patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 20032350–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puskas J D, Williams W H, Duke P G.et al Off‐pump coronary artery bypass grafting provides complete revascularization with reduced myocardial injury, transfusion requirements, and length of stay: a prospective randomized comparison of two hundred unselected patients undergoing off‐pump versus conventional coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003125797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meharwak S Z, Trehan T. Off pump coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Heart Surg Forum 2002541–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arom K V, Emery R W, Flavin T F.et al OPCAB surgery: a critical review of two different categories of preoperative ejection fraction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 200120533–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shennib H, Endo M, Benhamed O.et al Surgical revascularization in patients with poor left ventricular function: on or off‐pump? Ann Thorac Surg 200274s1344–s1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ascione R, Lloyd C, Underwood M.et al Economic outcome of off pump coronary artery bypass surgery: a prospective randomized study. Ann Thorac Surg 1999682237–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]