A Hypervariable Invertebrate Allodeterminant (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Apr 14.

Published in final edited form as: Curr Biol. 2009 Mar 19;19(7):583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.040

Summary

Colonial marine invertebrates, such as sponges, corals, bryozoans, and ascidians, often live in densely-populated communities where they encounter other members of their species as they grow over their substratum. Such encounters typically lead to a natural histocompatibility response in which colonies either fuse to become a single, chimeric colony or reject and aggressively compete for space. These allorecognition phenomena mediate intraspecific competition [1–3], support allotypic diversity [4], control the level at which selection acts [5–8], and resemble allogeneic interactions in pregnancy and transplantation [9–12]. Despite the ubiquity of allorecognition in colonial phyla, however, its molecular basis has not been identified beyond what is currently known about histocompatibility in vertebrates and protochordates. We positionally cloned an allorecognition gene using inbred strains of the cnidarian, Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus, which is a model system for the study of invertebrate allorecognition. The gene identified encodes a putative transmembrane receptor expressed in all tissues capable of allorecognition that is highly polymorphic and predicts allorecognition responses in laboratory and field-derived strains. This study reveals that a previously undescribed hypervariable molecule bearing three extracellular domains with greatest sequence similarity to the immunoglobulin superfamily is an allodeterminant in a lower metazoan.

Results and Discussion

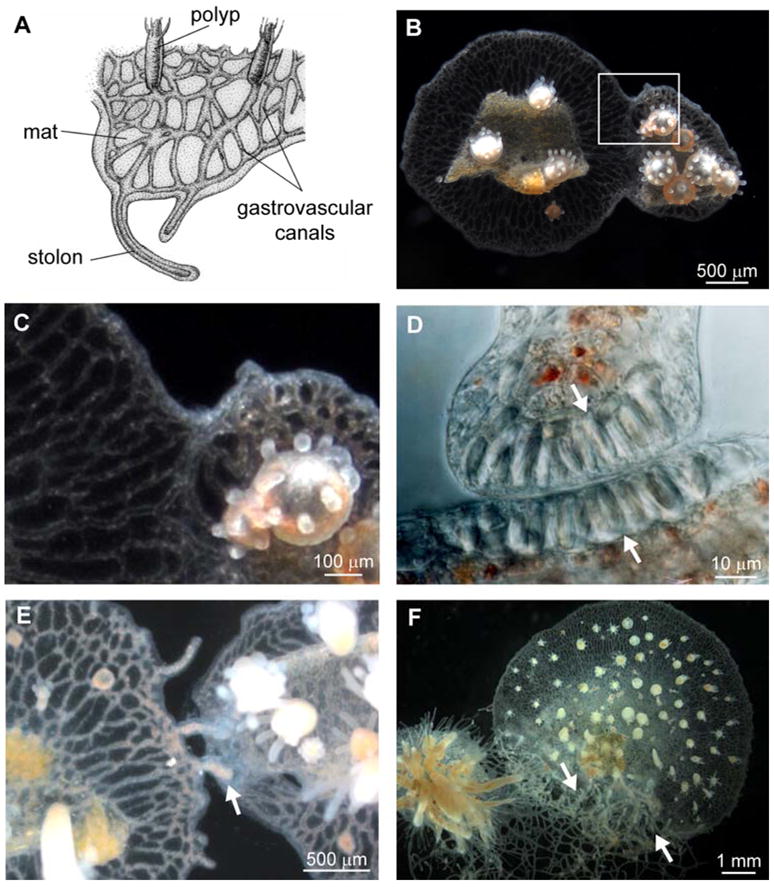

Hydractinia colonies consist of polyps specialized for feeding, reproduction, or defense, which bud from the mat, a sheet of two ectodermal cell layers that encase a network of endodermal gastrovascular canals (Figure 1A). Colonies grow by expanding the leading edge of the mat or by elongating stolons, ectodermally covered extensions of gastrovascular canals. When two Hydractinia colonies grow into contact, they undergo the fusion-rejection response. Fusion is characterized by ectodermal cell adhesion and establishment of a continuous gastrovascular system [13, 14] (Figure 1B and 1C). In contrast, rejection is characterized by failure of ectodermal cells to adhere and extensive recruitment of nematocytes to the contact site [13, 14]. Nematocytes are a cnidarian-specific cell type that contains nematocysts, harpoon-like organelles used for feeding and defense. Nematocytes at the contact site do not initially discharge their nematocysts but instead assemble at the colony margin (Figure 1D) and simultaneously fire following contact, destroying the foreign tissue. Additional nematocytes subsequently migrate to the contact zone and discharge their nematocysts once they are oriented toward the opposing colony [14]. During rejection responses, stolons frequently become hyperplastic, swelling with nematocytes, rising off the substrate, and growing over the opposing colony (Figure 1E and 1F) [13–15].

Figure 1.

Allorecognition in Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus. (A) Morphology of a Hydractinia colony. (B) Fusion between two Hydractinia colonies. (C) Magnification of the boxed area in B. (D) Magnification of a stolon tip and stolon flank from rejecting colonies, showing recruitment of nematocytes (arrowheads) to the contact point. (E) Early rejection, showing production of hyperplastic stolons (arrowhead). (F) Late stage rejection, showing proliferation of hyperplastic stolons (arrowheads). D, E, and F show different colonies. A modified from [37]. B and C reprinted with permission from [21]. F from [26]. D from [14], reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. © 1989.

Investigation of the genetics of allorecognition in Hydractinia began in the 1950s, when Hauenschild [16, 17] performed systematic breeding experiments in which he created two F2 populations derived from two separate pairs of wild-type colonies. He interpreted the results of these crosses using a single locus model of inheritance, but noted that this model did not explain a small proportion of fusibility results in the F1 and F2 generations. Later investigators similarly reported fusibility results inconsistent with simple, single-locus Mendelian inheritance in F1 and F2 populations derived from wild-type colonies [18]. Subsequently, our lab established inbred lines of Hydractinia and demonstrated that, in these lines, allorecognition segregated as a pair of tightly-linked loci, alr1 and alr2, which mapped to a 1.7 cM chromosomal interval [19–21] (Figure 2A). Within our inbred strains, two alleles (f and r) segregate at each locus. Colonies sharing at least one allele at both loci fuse, while colonies sharing no alleles at either locus reject. Colonies sharing alleles at only one locus undergo transitory fusion, which can be of two types [20, 21]. If colonies share at least one allele at alr2 and none at alr1, they initially fuse, but develop a gray band across the contact zone 1–3 days post-fusion, their gastrovascular canals become occluded, and they permanently separate within 1–3 days (type I transitory fusion) [20, 21]. In contrast, colonies sharing at least one allele at alr1 and none at alr2 fuse normally for 1–4 days, then display cycles of separation and re-fusion that continue indefinitely (type II transitory fusion) [21]. Thus, alr1 and alr2 jointly distinguish self from non-self.

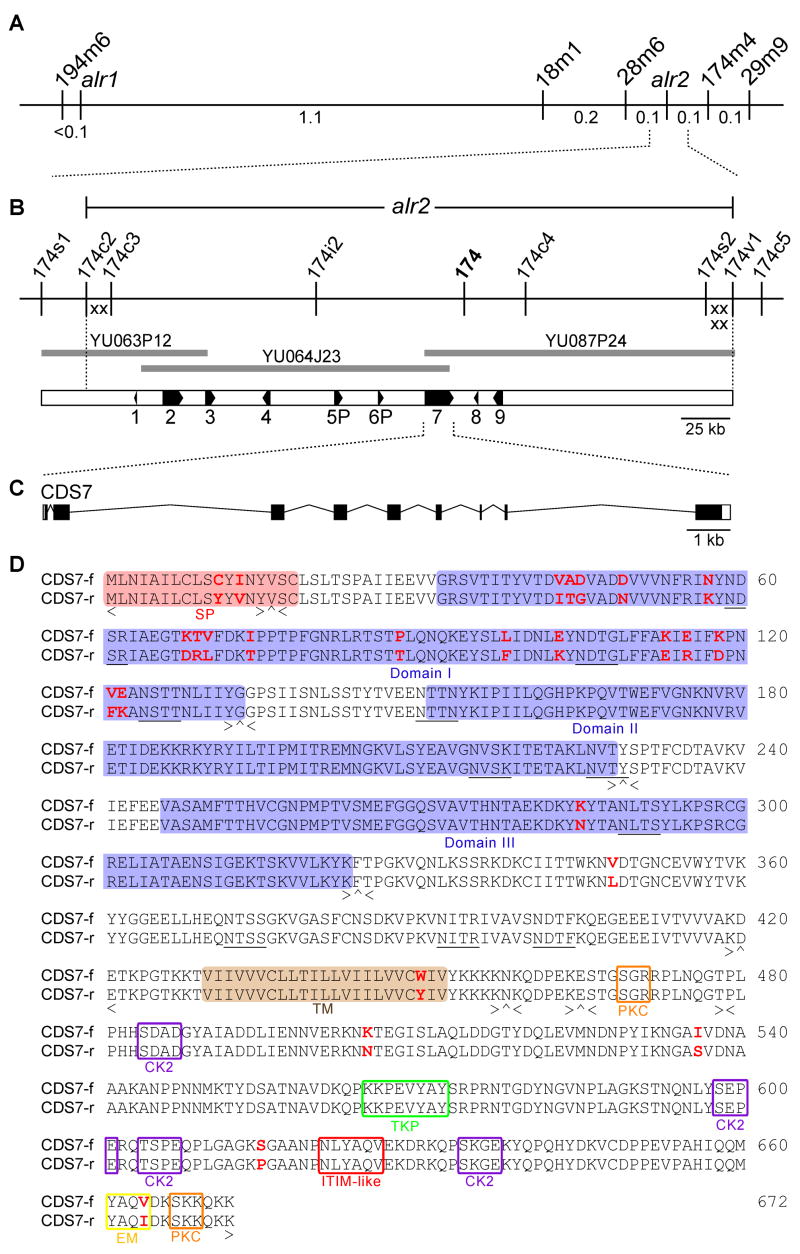

Figure 2.

Positional cloning of alr2. (A) Genetic map of the Hydractinia allorecognition complex, which contains two histocompatibility loci, alr1 and alr2. 194m6, 18m1, 28m6, 174m4, and 29m9 are markers used to map the interval. Genetic distances are shown below the line in centimorgans. (B) Physical map of the alr2 genomic region. Markers are derived from fosmid or BAC sequences. Recombination breakpoints defining the alr2 locus are shown as X’s. BAC clones comprising the minimum tiling path across the alr2 region are shown as heavy gray lines. Numbered boxes are expressed coding sequences. (C) Genomic organization of CDS7. White boxes, black boxes, and bent lines indicate UTRs, exons, and introns, respectively. (D) CDS7 amino acid sequence, showing alignment between the f and r alleles. SP = signal peptide, domains I-III = regions similar to Ig-like domains, TM = transmembrane domain; PKC = protein kinase C phosphorylation motif, TKP = tyrosine kinase phosphorylation motif, CK2 = casein kinase II phosphorylation motif, EM = endocytosis motif, ITIM-like = ITIM-like motif. Potential N-glycosylation sites are underlined. Exon organization is denoted below the alignment. < and > = amino acids encoded by the last complete codon of the left and right exon ends, respectively. ^ = codon spanning two exons.

Positional cloning and identification of an alr2 candidate gene

We positionally cloned alr2 using a tightly linked molecular marker (marker 174, Figure 2B) [20]. Bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) and fosmid genomic libraries were constructed from a laboratory strain homozygous for the f allele at both alr1 and alr2 (colony 833–8). We used previously identified recombinants [20, 21] to define the proximal and distal limits of the alr2 locus with six recombination breakpoints, localized to two ~15 kb regions at each end of the contig (X’s, Figure 2B).

The minimum tiling path over the alr2 region was sequenced and analyzed for putative coding sequences (CDS), of which we identified nine (Figure 2B and Table S1). For each CDS, we obtained a full-length cDNA sequence and analyzed expression via RT-PCR. Similarity searches comparing each putative CDS against protein and conserved domain databases identified these genes as likely homologs of a Nematostella malate dehydrogenase (CDS1), a mosquito hypothetical protein bearing ankyrin repeats and a KH RNA-binding domain (CDS2), bovine actin-related protein 8 (CDS3), chicken ATP synthase mitochondrial F1 complex assembly factor 2 (CDS4), and honeybee alpha-1,6-fucsosyltransferase (CDS8). The top BLAST hit for CDS7 was to a protein of unknown function from the nematode, Brugia malayi, while CDS9 was not similar to any known protein. The remaining two sequences, CDS5 and CDS6, were partial duplications of CDS7 (Figure S1). Although cDNA products for CDS5 and CDS6 were amplified via 5′ RACE, 3′ RACE experiments with the same cDNA pools successfully employed in all other RACE experiments failed repeatedly, suggesting these sequences lacked polyadenylation. In addition, CDS5 included a frame-shift mutation that inserted a stop codon in its third exon. These data led us to conclude that CDS5 and CDS6 were likely pseudogenes arising from tandem duplication of the CDS7 genomic region, and we therefore designated them CDS5P and CDS6P.

Initial evaluation of alr2 candidate genes used two criteria. The fact that allorecognition responses require cell-cell contact and involve tissue adhesion [13, 14] suggests alr2 is a membrane-associated protein. In addition, an alr2 candidate must display substantial polymorphism between histo-incompatible inbred strains, i.e., between f and r alleles. Only CDS7 proved to both encode a transmembrane protein and possess a highly polymorphic extracellular domain (Table S1). CDS7 was predicted to contain 9 exons with a 2.3 kb full-length cDNA encoding 672 amino acids (Figure 2D). The protein was a predicted type I transmembrane protein with an 18 amino acid (aa) signal peptide followed by a 411 aa extracellular region consisting of three domains, a single 23 aa transmembrane helix, and a 220 aa cytoplasmic domain. The cytoplasmic domain contained an endocytosis motif and potential phosphorylation sites for tyrosine kinase, protein kinase C and casein kinase II. We also searched CDS7 for immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) (Y-xx-I/L-x(6–12)-Y-xx-L/I, where x is any amino acid) and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) (I/L/V/S)-x-Y-xx-I/V/L), signaling motifs frequently found in the cytoplasmic domains of vertebrate immune receptors [22]. Although we did not locate any canonical ITAMs or ITIMs, we did find a single ITIM-like motif (N-x-Y-xx-V) previously identified on members of the leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor (LIR) family [23] (Figure 2D). Alignment of CDS7-f and CDS7-r revealed 26 aa polymorphisms, of which 17 were located in the 114 aa region encoded by exon 2 (Figure 2D). This level of polymorphism was the highest of any expressed sequence in the alr2 genomic region (Table S1). Southern blot hybridization was consistent with CDS7 being a single copy sequence in the Hydractinia genome (Figure S2).

BLASTP searches with CDS7 returned significant alignments to diverse proteins from the immunoglobulin superfamily. These alignments were exclusively between the extracellular portion of CDS7 encoded by exons 2, 3, and 4 (hereafter domains I, II, and III; Figure 2D) and full or partial immunoglobulin-like (Ig-like) domains. While the most significant alignment was to a hypothetical Brugia protein (2 × 10−6, 23% identity), most BLAST hits were to members of the IgLON family of neural cell adhesion molecules with similar _e-_values and % identities (see Supplemental Results and Discussion). To further explore the similarity between CDS7 and the Ig superfamily, we searched conserved domain databases and performed similarity searches based on tertiary structure, which should be sensitive to distant homologies. These methods consistently predicted Ig-like folds for domains I-III, with domain I most similar to V-set domains, and domains II-III most similar to I-set domains (Table S2). Multiple sequence alignments between domains I-III and canonical I- and V-set domains showed the Hydractinia domains matched the common V/I-set frame residues [24] at many positions, although only domain II possessed the highly conserved tryptophan and all domains lacked the hyperconserved cysteines characteristic of most Ig-like domains (Figure S3 and Supplemental Results and Discussion). Together, these analyses show that domains I-III are most similar to Ig-like domains and suggest that CDS7 could be a novel member of the Ig superfamily, albeit a distinct one.

BLAST searches against the only sequenced hydrozoan genome, Hydra magnipapillata, returned a single significant alignment between CDS7 domains I-III and three Ig-like domains from a predicted titin-like molecule (e = 0.009, 24% identity, scaffold ID: NW_002165237). Similarly, BLAST searches against the genome of the starlet anemone, Nematostella vectensis, returned significant alignments between domains II and III and several putative Ig-superfamily members, with the top hit to a predicted protein similar to mammalian neural cell adhesion molecules (e = 1 × 10−5, 27% identity, accession: XP_001637446). We found no synteny between the alr2 genomic region and the Nematostella genome, but did detect two small tracks of synteny between the alr2 interval and two different scaffolds in the Hydra genome assembly (Figure S4). Neither track of synteny included CDS7, and neither Hydra scaffold encoded any genes with immunoglobulin-like domains. TBLASTN searches with CDS7 against cnidarian ESTs did not return significant alignments. No significant similarity was detected between CDS7 and the FuHC and fester allorecognition proteins from the protochordate tunicate, Botryllus schlosseri [10, 25].

Expression of the alr2 candidate gene

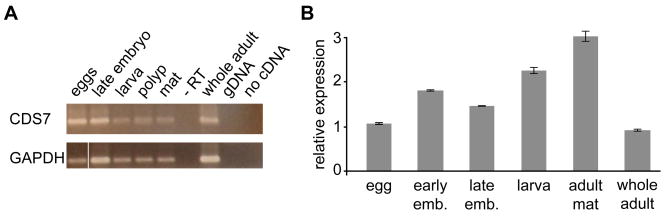

An alr2 candidate gene should be expressed in all tissues capable of allorecognition. In Hydractinia, late larval, polyp, and mat tissues display allorecognition phenomena [13, 14], while blastulae and early stage larvae do not [26, 27]. CDS7 expression was assayed qualitatively by RT-PCR in cDNA pools representing five tissue types (eggs, 64-cell embryos, 2–3 day old larvae, mat, and polyps) and was detectable in all tissues examined (Figure 3A). Quantitative RT-PCR showed that expression was highest in the adult mat tissue (Figure 3B). We suspect that the CDS7 expression we observed in early embryonic tissues reflects a need for allodeterminants to be deployed in earliest colony ontogeny, as Hydractinia colonies possess short-lived, non-feeding larvae that settle on hermit crab shells in a site-specific fashion and have a high probability of encountering conspecifics immediately post-metamorphosis [28].

Figure 3.

Expression of CDS7. (A) RT-PCR of cDNA isolated from different Hydractinia life stages and tissues. Top panel shows a 509 bp product amplified from exons 8–9 of CDS7. Bottom panel shows a 406 bp product amplified from GAPDH. −RT = control in which reverse transcriptase was omitted from cDNA synthesis. (B) Real-time PCR of CDS7. Relative expression shown for eggs, 2–8 cell embryos (early blastula), 64 cell embryos (late blastula), planulae, adult mat tissue, and whole adult colonies (polyps + mat).

Polymorphism and phenotype prediction of the alr2 candidate gene

To further characterize CDS7’s role as an allodeterminant, we employed a stringent test similar to that used to identify the FuHC histocompatibility locus in Botryllus [10]. Since Hydractinia colonies must share at least one allele at either alr1, alr2, or both to avoid rejection, and both fusion and transitory fusion are exceedingly rare between field-collected colonies [18, 19, 29], these loci are predicted to be highly polymorphic [4]. Moreover, pairs of field-collected colonies that do not reject should share at least one allele at either alr1 or alr2, which is an event unlikely to occur by chance [4].

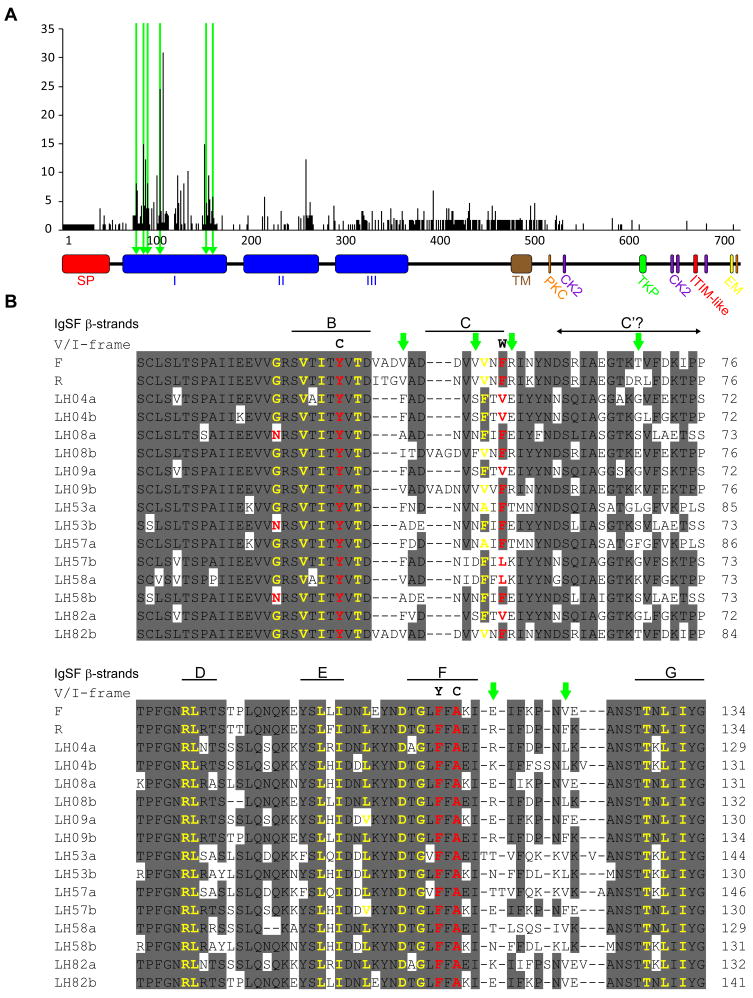

We assessed CDS7 polymorphism by examining alleles from our 2 inbred strains and 7 wild-type colonies for a total of 16 alleles. Domain I was highly variable (Figure 4A) and had an average of 31 pairwise differences between alleles. Although 68/111 amino acid positions in domain I differed between at least two alleles, most residues that aligned to the conserved V/I-frame residues in canonical Ig-like domains were invariant (Figure 4B). We also analyzed CDS7 for evidence of positive selection by identifying codons at which the estimated rate of nonsynonymous mutation exceeded that of synonymous mutation. Allorecognition systems are expected to be under positive frequency-dependent selection, which favors rare alleles [4]. Site-wise analysis using the HyPhy Statistical package [30] identified 6 positively selected codons, all within domain I (Figure 4B and Table S3). Thus, CDS7 had both of the hallmarks of frequency-dependent selection—high allele number at low frequency [31] and positively selected sites.

Figure 4.

Variability of CDS7. (A) High levels of per-site variability suggest positive selection for diversity over CDS7. Variability was calculated as (number of different residues)/(frequency of the most common residue) − 1. Triangles and green bars indicate sites demonstrating significant departures from neutrality, suggesting positive selection. CDS7 domains labeled as in Figure 2. (B) PRANKF [25] alignment of domain I from 16 CDS7 alleles. Eight or more consensus residues are shaded gray. Green arrowheads indicate positions under positive selection. Residues matching the conserved V/I-frame are in yellow, those that differ are in red with V/I-frame consensus residues shown above. Beta-strand positions in canonical Ig-like domains relative to the putative V/I-frame residues are shown above the alignment.

To test whether CDS7 could predict allorecognition responses, we screened field-collected colonies for their ability to fuse to inbred colonies bearing either f (n=497) or r (n=508) alleles at alr1 and alr2. Only two colonies (0.2%) failed to reject laboratory strains. Colony LH416 displayed type II transitory fusion against the f tester colony, consistent with an _f-_like allele at alr1, while colony LH82 displayed type I transitory fusion against the f tester colony, consistent with an _f-_like allele at alr2. We sequenced full-length cDNAs for the two CDS7 alleles from LH82 (designated a and b), as well as the genomic regions encoding them. Predicted amino acid sequences of the a and f alleles differed at 41/672 sites, including 31/119 sites in domain I. In contrast, the b and f alleles were 100% identical over domain I and differed at only 7/672 sites overall (1 in the signal peptide, 1 in domain III, 1 in the remaining extracellular domain, and 4 in the cytoplasmic domain). A testcross between LH82 (CDS7-a/b) and a colony homozygous for r at both allorecognition loci demonstrated that the CDS7-b allele cosegregated with an ability to display transitory fusion against colonies bearing CDS7-f alleles (number of offspring in cross=12; 5 CDS7-a/r offspring, all rejected homozygous f tester; 7 CDS7-b/r offspring, all displayed transitory fusion to homozygous f tester). Thus, the only wild-type colony with a phenotype suggesting it shared a common alr2 allele with our f inbred line also carried a CDS7 allele 100% identical to the f allele over the hypervariable extracellular domain. More extensive analysis of the map between sequence variation and fusibility in natural populations is now underway.

Because our data indicated that CDS7 was an allodeterminant in our inbred lines, displayed extensive natural polymorphism, and predicted allorecognition responses between our inbred lines and field-collected colonies, we concluded it was alr2. Identification of this cnidarian histocompatibility gene creates an immediate opportunity to address several long-standing questions about invertebrate allorecognition, including the population genetic mechanisms maintaining variation, the role that chimerism plays in the distribution and abundance of colonial organisms, and the degree of conservation, if any, between allorecognition systems in colonial taxa. In addition, relationships have often been suggested between cnidarian and protochordate allorecognition systems or between invertebrate allorecognition systems and elements of the vertebrate immune system, particularly the MHC. While Ig-like domains are found in vertebrate immune molecules, the Botryllus FuHC gene, and potentially alr2, there appears to be no additional similarity between the known surface molecules in these three systems. Indeed, growing evidence suggests that animals have evolved a variety of unique molecular mechanisms to distinguish self from non-self, including the MHC in vertebrates, VCBPs in protochordates [32], VLR immune molecules in jawless fish [33], FREP proteins in molluscs [34], and the FuHC in tunicates [10]. We can now add the Hydractinia allorecognition system to this diversity. It remains possible, however, that invertebrate and vertebrate histocompatibility systems share downstream signaling pathways. The presence of an ITIM-like motif in the cytoplasmic domain of alr2 suggests it could be phosphorylated by SH2-domain containing protein tyrosine phosphotases similar to those involved in inhibitory signaling in the vertebrate immune system. As additional molecular data become available for Hydractinia and other invertebrate allorecognition systems, we will finally be able to address these questions.

Experimental Procedures

Detailed experimental procedures are provided in Supplemental Data, but are summarized here.

Positional Cloning

Fosmid and BAC libraries were constructed using DNA from an inbred colony homozygous for the f allele at alr1 and alr2. Clones isolated during the chromosome walk were assembled into contigs using restriction digest fingerprinting [35], with overlaps confirmed by PCR. The minimum tiling path of the alr2 region was sequenced through the Community Sequencing Project of the Joint Genome Institute, US Department of Energy.

Sequence Analysis and CDS identification

Potential coding sequences were identified using a combination of BLAST similarity searches and ab initio gene prediction algorithms. Full-length cDNAs of f alleles were obtained by RACE and RT-PCR experiments using the GeneRacer Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Expression Assays

First-strand cDNA pools were created from eggs, blastulae, larvae, polyp, and mat tissues using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) primed with the Oligo-dT primer supplied in the GeneRacer Kit. CDS7 expression was assessed qualitatively by RT-PCR by amplification of a 509 bp fragment spanning exons 6–9. As a control, a 406 bp region of GAPDH spanning the predicted stop codon was used. For real-time quantitative PCR, primers amplifying a 156 bp region of exons 8–9 of CDS7 or a 117 bp region of exons 4–5 of GAPDH were used.

Polymorphism and Selection Analyses

For each candidate gene, a full-length cDNA sequence of the f alleles was obtained by RT-PCR. Sequences of r alleles were predicted by mapping the cDNA sequence of the f allele onto the genomic sequence of the r haplotype, which was obtained using a BAC library constructed from an inbred colony homozygous for the r allele at alr1 and alr2 and kindly provided by Luis Cadavid (National University of Columbia).

For CDS7, full length cDNA sequences were obtained from the 2 inbred alleles plus 7 wild-type colonies, for a total of 16 alleles. Predicted amino acid sequences were aligned with PRANK+F [36]. For positive selection analyses, the alignment was back-translated to generate a nucleic acid alignment. Site-wise maximum-likelihood analyses for positive selection were performed with the Datamonkey server, which runs the HyPhy software package [30]. We reported sites to be under positive selection if they received significant scores under two out of three different codon-based maximum likelihood methods (SLAC, REL, and FEL).

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Altland, C. Glastris, E. Buss, S. Lubner and T. Wu for technical assistance, L. Cadavid for providing BAC clones of the r haplotype, and A. Signorovitch, M. Flajnik and L. Du Pasquier for discussion. Supported by NIH grant 1R21-AI066242 (F.L, S.D, and L.B), NSF grant IOS-0818295 (L.B and S.D.), the American Society of Nephrology (F.L.), and the Joint Genome Institute’s Community Sequencing Program (L.B. and S.D). M.N was supported by a US Department of Education GAANN Fellowship, A.P. was supported by NIH Training Grant T32-GM07499 in Genetics, and R.R. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. alr2 sequences available in Genbank (EU219736, FJ207397-FJ207400, FJ207403-FJ207409, FJ617565-FJ617568).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Francis L. Intraspecific aggression and its effect on the distribution of Anthopleura elegantissima and some related sea anemones. Biol Bull. 1973;144:73–92. doi: 10.2307/1540148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buss LW, Grosberg RK. Morphogenetic basis for phenotypic differences in hydroid competitive behaviour. Nature. 1990;343:63–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buss LW. Competition within and between encrusting clonal invertebrates. Trends Ecol Evol. 1990;5:352–356. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(90)90093-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grosberg RK. The evolution of allorecognition specificity in clonal invertebrates. Q Rev Biol. 1988;63:377–412. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoner DS, Rinkevich B, Weissman IL. Heritable germ and somatic cell lineage competitions in chimeric colonial protochordates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9148–9153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buss LW. Somatic cell parasitism and the evolution of somatic tissue compatibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:5337–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.17.5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buss LW. The Evolution of Individuality. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laird DJ, De Tomaso AW, Weissman IL. Stem cells are units of natural selection in a colonial ascidian. Cell. 2005;123:1351–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnet FM. “Self-recognition” in colonial marine forms and flowering plants in relation to the evolution of immunity. Nature. 1971;232:230–235. doi: 10.1038/232230a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Tomaso AW, Nyholm SV, Palmeri KJ, Ishizuka KJ, Ludington WB, Mitchel K, Weissman IL. Isolation and characterization of a protochordate histocompatibility locus. Nature. 2005;438:454–459. doi: 10.1038/nature04150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litman GW, Cannon JP, Dishaw LJ. Reconstructing immune phylogeny: New perspectives. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:866–879. doi: 10.1038/nri1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laird DJ, De Tomaso AW, Cooper MD, Weissman IL. 50 million years of chordate evolution: seeking the origins of adaptive immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6924–6926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.6924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buss LW, McFadden CS, Keene DR. Biology of hydractiniid hydroids. 2 Histocompatibility effector system competitive mechanism mediated by nematocyst discharge. Biol Bull. 1984;167:139–158. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lange R, Plickert G, Müller WA. Histoincompatibility in a low invertebrate, Hydractinia echinata: analysis of the mechanism of rejection. J Exp Zool. 1989;249:284–292. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivker FB. A hierarchy of histo-incompatibility in Hydractinia echinata. Biol Bull. 1972;143:162–174. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauenschild C. Über die Vererbung einer Gewebeverträglichkeitseigenschaft bei dem Hydroidpolypen Hydractinia echinata. Z Naturforsch Pt B. 1956;11:132–138. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauenschild C. Genetische und entwichlungphysiologische Untersuchungen über Intersexualität und Gewebeverträlichkeit bei Hydractinia echinata Flem. Roux Arch Dev Biol. 1954;147:1–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00576821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosberg RK, Levitan DR, Cameron BB. Evolutionary genetics of allorecognition in the colonial hydroid Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus. Evolution. 1996;50:2221–2240. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokady O, Buss LW. Transmission genetics of allorecognition in Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus (Cnidaria:Hydrozoa) Genetics. 1996;143:823–827. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.2.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadavid LF, Powell AE, Nicotra ML, Moreno M, Buss LW. An invertebrate histocompatibility complex. Genetics. 2004;167:357–365. doi: 10.1534/genetics.167.1.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell AE, Nicotra ML, Moreno MA, Lakkis FG, Dellaporta SL, Buss LW. Differential effect of allorecognition loci on phenotype in Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa) Genetics. 2007;177:2101–2107. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.075689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrow AD, Trowsdale J. You say ITAM and I say ITIM, let’s call the whole thing off: the ambiguity of immunoreceptor signalling. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1646–1653. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cosman D, Fanger N, Borges L. Human cytomegalovirus, MHC class I and inhibitory signalling receptors: more questions than answers. Immunol Rev. 1999;168:177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harpaz Y, Chothia C. Many of the immunoglobulin superfamily domains in cell adhesion molecules and surface receptors belong to a new structural set which is close to that containing variable domains. J Mol Biol. 1994;238:528–539. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nyholm SV, Passegue E, Ludington WB, Voskoboynik A, Mitchel K, Weissman IL, De Tomaso AW. fester, a candidate allorecognition receptor from a primitive chordate. Immunity. 2006;25:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poudyal M, Rosa S, Powell AE, Moreno M, Dellaporta SL, Buss LW, Lakkis FG. Embryonic chimerism does not induce tolerance in an invertebrate model organism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4559–4564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608696104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lange RG, Dick MH, Müller WA. Specificity and early ontogeny of historecognition in the hydroid Hydractinia. J Exp Zool. 1992;262:307–316. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yund PO, Cunningham CW, Buss LW. Recruitment and postrecruitment interactions in a colonial hydroid. Ecology. 1987;68:971–982. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicotra ML, Buss LW. A test for larval kin aggregations. Biol Bull. 2005;208:157–158. doi: 10.2307/3593147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pond SLK, Frost SDW. Datamonkey: rapid detection of selective pressure on individual sites of codon alignments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2531–2533. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright S. The distribution of self-sterility alleles in populations. Genetics. 1939;24:538–552. doi: 10.1093/genetics/24.4.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cannon JP, Haire RN, Litman GW. Identification of diversified genes that contain immunoglobulin-like variable regions in a protochordate. Nature Immunol. 2002;3:1200–1207. doi: 10.1038/ni849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pancer Z, Amemiya CT, Ehrhardt GRA, Ceitlin J, Larry Gartland G, Cooper MD. Somatic diversification of variable lymphocyte receptors in the agnathan sea lamprey. Nature. 2004;430:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature02740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang SM, Adema CM, Kepler TB, Loker ES. Diversification of Ig superfamily genes in an invertebrate. Science. 2004;305:251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.1088069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marra MA, Kucaba TA, Dietrich NL, Green ED, Brownstein B, Wilson RK, McDonald KM, Hillier LW, McPherson JD, Waterston RH. High throughput fingerprint analysis of large-insert clones. Genome Res. 1997;7:1072–1084. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.11.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loytynoja A, Goldman N. Phylogeny-aware gap placement prevents errors in sequence alignment and evolutionary analysis. Science. 2008;320:1632–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1158395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buss LW, Blackstone NW. An experimental exploration of Waddington epigenetic landscape. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1991;332:49–58. [Google Scholar]