Treatment of rectal prolapse in children with cow milk injection sclerotherapy: 30-year experience (original) (raw)

Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the role and our experience of injection sclerotherapy with cow milk in the treatment of rectal prolapse in children.

METHODS: In the last 30 years (1976-2006) we made 100 injections of sclerotherapy with cow milk in 86 children. In this study we included children who failed to respond to conservative treatment and we perform operative treatment.

RESULTS: In our study we included 86 children and in all of the patients we perform cow milk injection sclerotherapy. In 95.3% (82 children) of patients sclerotherapy was successful. In 4 (4.7%) patients we had recurrent rectal prolapse where we performed operative treatment. Below 4 years we had 62 children (72%) and 24 older children (28%). In children who needed operative treatment we performed Thiersch operation and without any complications.

CONCLUSION: Injection sclerotherapy with cow milk for treatment rectal prolapse in children is a simple and effective treatment for rectal prolapse with minimal complications.

Keywords: Rectal prolapse, Sclerotherapy with cow milk, Children

INTRODUCTION

Prolapse of the rectum is a herniation of the rectum through the anus[1]. The herniation may be mucosal and may involve only a small ring of mucosa or involve all layers of the rectum (procidentia). These conditions are most common from 3-5 years of age and usually first detected by the childs' parents and usually spontaneously reduce. Parents often provide history of a dark red mass protruding from the childs’ anus and the child appears to be pain free[2]. Prolapse of the rectum, which involve only the mucosa, is the least serious form and is most common in the pediatric population[3].

The most common form of rectal prolapse is idiopathic. At this age a child’s muscle mass is not well developed and the rectum is loosely adherent to the underlying muscles. These children also spend long periods straining to evacuate their rectum with hips and knees flexed while sitting on a children’s “potty”[4]. Children with conditions such as rectal polyps, diarrhea, malnutrition, worms, proctitis, ulcerative colitis congenital megacolon, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and cystic fibrosis also may have rectal prolapse. Rectal prolapse is common in children with exstrophy of bladder and myelomeningocoele or in similar conditions associated with weakness pelvic musculature or its innervation[5].

Rectal prolapse often occurs with defecation or crying and reduces spontaneously. Failure to reduce may lead to venous stasis, edema and possibly ulcerations. When prolapse is present it is not possible to insert fingers in the space between the prolapsed bowel and anus. The prolapsed bowel may be grasped with lubricated fingers and pushed back in by the parents. If rectal prolapse persists for a long time the bowel becomes edematous and firm steady pressure for several minutes may be necessary to reduce the swelling and allow for reduction[6]. After reduction digital rectal examination is necessary to verify complete reduction. If prolapse immediately recurs, reduction is again necessary and the buttocks strapped together with a single band of adhesive tape for several hours[7].

Most patients with children’s rectal prolapse do not require any specific form of treatment; however, it is necessary to prevent excessive straining. Treatment should be directed at dietary correction of constipation, proper toilet training, and at elimination of any underlying disturbance such as parasitic infection, polyps or diarrhea. Oral administration of stool softeners and having the child defecate with feet off the floor may be helpful[8]. Prolonged sessions on the toilet should be discouraged[9]. When parents observe rectal prolapse, reduction of protrusion is aided by pressure with warm compresses and gently push it into the rectum. An immediate replacement of rectal prolapse is necessary to avoid swelling and possible later difficulty in reduction[10]. If edema of the rectum persists, firm steady pressure of the fingertips for several minutes may be necessary to reduce swelling and permit reduction of the prolapse[11]. Surgical procedures may be required for recurrent rectal prolapse refractory to conservative measures[12]. If repetitive attempts at medical therapy have failed and conservative treatments also failed, and the prolapse persists, submucosal injection of sclerosans into the rectal ampula should be done. Children with recurrence after injection of sclerosans require surgical treatment[13].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical features

In children with rectal prolapse, before any treatment, we performed sweat chloride test to rule out cystic fibrosis since the incidence of rectal prolapse in patients with cystic fibrosis ranges from 11%-23%[14]. We also obtained patients' stool for ova and parasites. Rectal prolapse has been associated with Escherichia coli, antibiotic-associated colitis, Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia, Salmonella, Shigella, and Trichuris species. Children with recurrent rectal prolapse, with no found underlying causes, should undergo proctosigmoidoscopy to rule out rectal polyps or other rectal lesions[14]. If found, the underlying cause of the prolapse should be treated. Most patients with children's rectal prolapse do not require any specific form of treatment, however, it is necessary to prevent excessive straining. Prolonged sessions on the toilet should be discouraged[15].

In the last 30 years (1976-2006) we had 483 patients with rectal prolapse. Three hundred and ninety seven patients with children's rectal prolapse did not require any specific form of treatment, it is necessary to prevent excessive straining. In this study we included children who failed to respond to conservative treatment and we performed sclerotherapy. In 86 patients repetative attemps at medical therapy failed and conservative treatment also failed and the prolapse persisted; here submucosal injection of sclerosans into the rectal ampula should be done.

Methods

We made 100 injections of sclerotherapy with cow milk in 86 patients. In this study we used conservative treatments and also performed operative treatments. We included 86 children and in all of patients we performed operative treatment. In all children we excluded allergic reactions to cow milk. In 95.3% (82 children) of patients the sclerotherapy was successful and in 4 (4.7%) children we performed operative treatment. Below 4 years we had 62 children (72%) and 24 older children (28%). The youngest boy was 8 mo. old and oldest was 8 years old. The mean age of the patients treated with sclerotherapy was 3.6 years. In 4 children, who needed operative treatment for recurrent rectal prolapse after three cow milk injections of sclerotherapy, we performed the Thiersch operation without complications. The youngest patient with Thiersch operation was 4 years old and oldest girl was 8 years old, the mean age of the patients was 6.2 years.

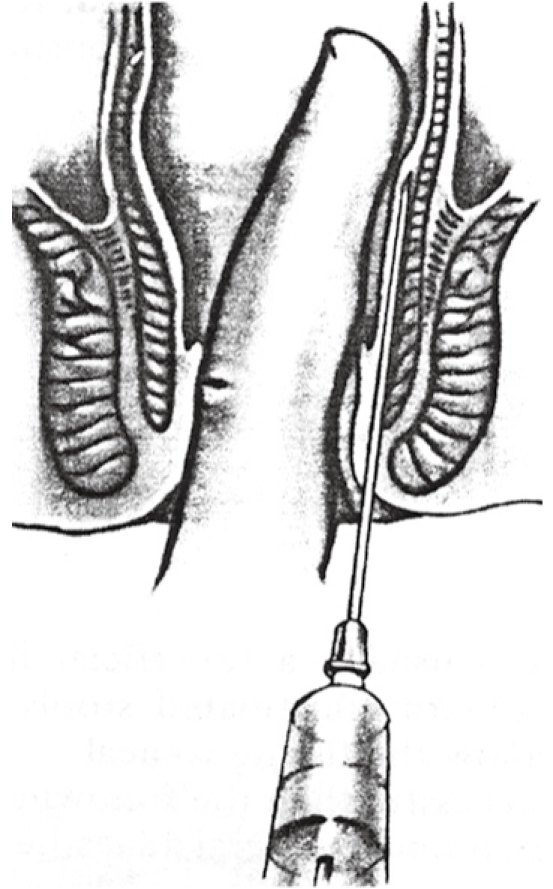

The technique of sclerotherapy is not difficult, but the surgeon should have experience with this method. The rectum is emptied with suppository and not with an enema. The patient is in the lithotomy position. A long needle is attached to an injection syringe inserted through the skin just outside the mucocutaneos junction and guided to the proper position using a finger in the rectum[16]. Two or three milliters of cow milk are injected along the rectal submucosa at the depth of 4-5 cm at four different quadrants (Figure 1). In 76 patients, we perform one cow milk injection, in 6 patients two cow milk injections, and in 4 patients three cow milk injections. In these 4 patients with three cow milk injections we performed operative surgical treatment (Table 1). This technique, submucosal injection of sclerosans into the rectal ampula, is designed to produce a perirectal inflammatory reaction to induce scarring and prevent prolapse[17]. Before application of cow milk, the milk was boiled for 10 min. Afterwards, the milk was cooled and application was possible.

Figure 1.

Cow milk is injected along the rectal submucosa.

Table 1.

Rectal prolapse in the last 30 years (n = 483 children)

| Treatment | n |

|---|---|

| Conservative | 397 |

| Sclerotherapy | 86 |

| One injection | 76 |

| Two injections | 6 |

| Three injections | 4 |

| Operative | 4 |

In children with recurrent rectal prolapse, after three cow milk injection sclerotherapies, we performed the Thiersch procedure for rectal prolapse. The Thiersch technique consists of a small incision in the perianal skin at 6 and 12 o’clock[18]. We performed the Thiersch operation with wire in two patients and two patients with a nonabsorbable suture. Through anterior and posterior skin incisions a wire is passed around the anal canal just proximal to the external anal sphincter and tied at an appropriate tension (tie wire/nonabsorbable suture just tight enough to prevent rectum prolapsing and just loose enough to let pass stool)[19]. This wire is tied over a 12 (infant) to 20 (adolescent) Hegar dilator or surgeon’s finger placed into the rectum. The therapy is effective to mechanically prevent rectum prolapsing, but it does not treat the underlying disorder. The purpose of this procedure is to keep the rectum from prolapsing by restricting the size of the anal lumen[20].

RESULTS

In the last 30 years (1976-2006) we made 100 injection sclerotherapies with cow milk in 86 children. In this study, we included children who failed to respond to conservative treatment and then we performed operative treatment.

In our study we included 86 children and in all patients we performed cow milk injection sclerotherapy. In 95.3% (82 children) of patients the sclerotherapy was successful and in 4 children with recurrent rectal prolapse we performed operative treatment. We had 62 children (72%) younger than 4 years and 24 older children (28%). The mean age for children with sclerotherapy was 3.6 years. In children who needed operative treatment we performed the Thiersch operation and no children had complications. The mean age of the children with the Thiersch operation was 6.2 years.

When we performed cow milk sclerotherapy every patient had a fever for 2 d and no antibiotics were administrated. We had only one patient who had inflammation in the place where milk was performed and incision was performed. After the Thiersch operation, fortunately, the wire was not rejected by the body and patients did not have enough scar tissue formed to improve control of the anus and to delay the return to the prolapse for months or years after removal of the wire or nonabsorbable suture. The wire was removed 6 mo after the Thiersch operation.

DISCUSSION

There is no optimal or standard procedure for treatment of rectal prolapse[21]. Although in excess of many different operations which have been described so far, some more popular than the others, we performed two procedures in our children’s hospital[22].

Most patients with children’s rectal prolapse do not require any specific form of treatment; however, it is necessary to prevent excessive straining. Treatment should be directed to dietary correction of constipation, to proper toilet training, and to the elimination of any underlying disturbance such as parasitic infection, polyps or diarrhea. Oral administration of stool softeners and having the child defecate with feet off the floor may be helpful. Prolonged sessions on the toilet should be discouraged.

If conservative treatment was not effective, cow milk injection sclerotherapy is simple and should be considered as the first line treatment of recurrent prolapse. We did not use a sclerosant agent such as 30% saline or phenol in almond oil because cow milk as sclerosing agent is inexpensive, easy for application, and the procedure is safe with no side effects[23]. We had only one complication involving inflammation of the perianal tissue. This procedure involves a 2 d stay in hospital after sclerotherapy.

In children with recurrent rectal prolapse following three cow milk injection sclerotherapies, we performed the Thiersch procedure for rectal prolapse[24]. In 4 children we performed operative treatment, the Thiersch operation. This procedure involves a 2 d stay in hospital after the operation. We did not have any complications after the procedure and the wire was removed 6 mo after the operation[25]. All patients, after the operation, did not have recurrent rectal prolapse.

Rectal prolapse is an intussusception of the rectum, which may be categorized as mucosal or complete. Mucosal prolapse involves protrusion of the mucosa only with the muscular layers of the rectum remaining in place[26]. Complete rectal prolapse or rectal procidentia involves full-thickness protrusion of the rectum through the anus.

Most patients with children’s rectal prolapse do not require any specific form of treatment, but it is necessary to prevent excessive straining. Treatment should be directed at dietary correction of constipation, to proper toilet training, and to the elimination of any underlying disturbance such as parasitic infection, polyps or diarrhea. Oral administration of stool softeners and having the child defecate with feet off the floor may be helpful. Prolonged sessions on the toilet should be discouraged.

Surgical procedure may be required for recurrent rectal prolapse refractory to conservative measures. If repetitive attempts at medical therapy have failed and conservative treatment has also failed, and the prolapse persists, submucosal injection of sclerosans into the rectal ampula should be done[27]. Cow milk as a sclerosing agent did not cause any complications. Injection sclerotherapy is simple and effective way to treatment for rectal prolapse in children[28]. Children with recurrence after three injections of sclerosing agent require operative surgical treatment[29].

In the last 30 years (1976-2006) we have performed 100 injection sclerotherapies with cow milk in 86 children. In 95.3% (82 children) of patients the sclerotherapy was successful and in 4 children we performed operative treatment. In children who needed operative treatment we performed the Thiersch operation and no children developed complications[30].

Both surgical treatments (cow milk sclerotherapy and the Thiersch operation) which we performed in our hospital in the last 30 years were very effective, inexpensive, easily available with only 2 d stay in hospital. The results were very good after cow milk sclerotherapy (95.3% patients without recurrence), and 4 patients after the Thiersch procedure were without recurrent rectal prolapse.

COMMENTS

Background

Prolapse of the rectum is a herniation of the rectum through the anus. The herniation may be mucosal and may involve only a small ring of mucosa or involve all layers of the rectum (procidentia).

Research frontiers

Most patients with children's rectal prolapse do not require any specific form of treatment; however, it is necessary to prevent excessive straining. Treatment should be directed at dietary correction of constipation, to proper toilet training, and to the elimination of any underlying disturbance such as parasitic infection, polyps or diarrhea.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Cow milk as a sclerosing agent is inexpensive, easy for application, the procedure is safe with no side effects. Injection sclerotherapy is a simple and effective way to treat rectal prolapse in children. Submucosal injection of sclerosans into the rectal ampula is designed to produce perirectal inflammatory reaction to induce scarring and prevent prolapse. Before cow milk application, the milk was boiled for 10 minutes. After that, the milk was cooled and application was possible.

Applications

In 76 patients (88.3%) we perform one cow milk injection and 95.3% patients were without recurrence. Cow milk is inexpensive, easy for application and without contraindications, except cow milk allergy.

Terminology

Rectal prolapse: Herniation of the rectum through the anus. Sclerotherapy: Submucosal injection of sclerosans into the rectal ampula, is designed to produce perirectal inflammatory reaction to induce scarring and prevent prolapse.

Peer review

The authors reported their long term experience with the treatment of rectal prolapse in children. In relapsing cases they reported a high success rate with cow milk sclerotherapy. This is an interesting manuscript.

Peer reviewer: Peter Laszlo Lakatos, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, 1st Department of Medicine, Semmelweis University, Koranyi S 2A, Budapest H1083, Hungary

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Rippe RA E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Ibanez V, Gutierrez C, Garcia-Sala C, Lluna J, Barrios JE, Roca A, Vila JJ. The prolapse of the rectum. Treatment with fibrin adhesive. Cir Pediatr. 1997;10:21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gourgiotis S, Baratsis S. Rectal prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:231–243. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groff DB, Nagaraj HS. Rectal prolapse in infants and children. Am J Surg. 1990;160:531–532. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antao B, Bradley V, Roberts JP, Shawis R. Management of rectal prolapse in children. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1620–1625. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Heest R, Jones S, Giacomantonio M. Rectal prolapse in autistic children. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:643–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siafakas C, Vottler TP, Andersen JM. Rectal prolapse in pediatrics. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1999;38:63–72. doi: 10.1177/000992289903800201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azimuddin K, Khubchandani IT, Rosen L, Stasik JJ, Riether RD, Reed JF 3rd. Rectal prolapse: a search for the "best" operation. Am Surg. 2001;67:622–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown AJ, Anderson JH, McKee RF, Finlay IG. Strategy for selection of type of operation for rectal prolapse based on clinical criteria. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:103–107. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerrero RA, Cavender CP. Constipation: physical and psychological sequelae. Pediatr Ann. 1999;28:312–316. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19990501-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loredo-Abdala A, Trejo-Hernandez J, Monroy-Villafuerte A, Bustos-Valenzuela V, Perea-Martinez A. Rectal prolapse in pediatrics. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2000;39:131–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramachandran P, Vincent P, Prabhu S, Sridharan S. Rectal prolapse of intussusception--a single institution's experience. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2006;16:420–422. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pikarsky AJ, Joo JS, Wexner SD, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Agachan F, Iroatulam A. Recurrent rectal prolapse: what is the next good option? Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1273–1276. doi: 10.1007/BF02237435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fahmy MA, Ezzelarab S. Outcome of submucosal injection of different sclerosing materials for rectal prolapse in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:353–356. doi: 10.1007/s00383-004-1197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabra SK, Kabra M, Lodha R, Shastri S, Ghosh M, Pandey RM, Kapil A, Aggarwal G, Kapoor V. Clinical profile and frequency of delta f508 mutation in Indian children with cystic fibrosis. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40:612–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rittmeyer C, Nakayama D, Ulshen MH. Lymphoid hyperplasia causing recurrent rectal prolapse. J Pediatr. 1997;131:487–488. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)80086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fengler SA, Pearl RK, Prasad ML, Orsay CP, Cintron JR, Hambrick E, Abcarian H. Management of recurrent rectal prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:832–834. doi: 10.1007/BF02055442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasaki Y, Iwai N, Kimura O, Hibi M. The treatment of rectal prolapse in children with phenol in almond oil injection. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004;14:414–417. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-821151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abes M, Sarihan H. Injection sclerotherapy of rectal prolapse in children with 15 percent saline solution. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004;14:100–102. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thiersch C. Carl Thiersch 1822-1895. Concerning prolapse of the rectum with special emphasis on the operation by Thiersch. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:154–155. doi: 10.1007/BF02562653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoab SS, Saravanan B, Neminathan S, Garsaa T. Thiersch repair of a spontaneous rupture of rectal prolapse with evisceration of small bowel through anus - a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:W6–W8. doi: 10.1308/147870807X160362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi S, Masuda H, Hayashi I, Sato H, Takayama T. Simple technique for repair of complete rectal prolapse using a circular stapler with Thiersch procedure. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:124–127. doi: 10.1080/11024150252884368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown AJ, Anderson JH, McKee RF, Finlay IG. Surgery for occult rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:176–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi JS, Hwang YH, Salum MR, Weiss EG, Pikarsky AJ, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Outcome and management of patients with large rectoanal intussusception. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:740–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hachiro Y, Kunimoto M, Abe T, Kitada M, Ebisawa Y. Aluminum potassium sulfate and tannic Acid injection in the treatment of total rectal prolapse: early outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1996–2000. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9060-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta PJ. Combined Thiersch’s procedure and subanodermal coagulation for complete rectal prolapse in the elderly. Dig Surg. 2006;23:146–149. doi: 10.1159/000094346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Sibai O, Shafik AA. Cauterization-plication operation in the treatment of complete rectal prolapse. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:51–54; discussion 54. doi: 10.1007/s101510200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shafik A. Mucosal plication in the treatment of partial rectal prolapse. Pediatr Surg Int. 1997;12:386–388. doi: 10.1007/BF01076946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan WK, Kay SM, Laberge JM, Gallucci JG, Bensoussan AL, Yazbeck S. Injection sclerotherapy in the treatment of rectal prolapse in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:255–258. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90441-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gysler R, Morger R. Sclerosing treatment with ethoxysclerol in anal prolapse in children. Z Kinderchir. 1989;44:304–305. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1043258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah A, Parikh D, Jawaheer G, Gornall P. Persistent rectal prolapse in children: sclerotherapy and surgical management. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:270–273. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1384-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]