Platelet α–granules: Basic biology and clinical correlates (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Jul 1.

Summary

α–Granules are essential to normal platelet activity. These unusual secretory granules derive their cargo from both regulated secretory and endocytotic pathways in megakaryocytes. Rare, inheritable defects of α–granule formation in mice and man have enabled identification of proteins that mediate cargo trafficking and α–granule formation. In platelets, α–granules fuse with the plasma membrane upon activation, releasing their cargo and increasing platelet surface area. The mechanisms that control α–granule membrane fusion have begun to be elucidated at the molecular level. SNAREs and SNARE accessory proteins that control α–granule secretion have been identified. Proteomic studies demonstrate that hundreds of bioactive proteins are released from α–granules. This breadth of proteins implies a versatile functionality. While initially known primarily for their participation in thrombosis and hemostasis, the role of α–granules in inflammation, atherosclerosis, antimicrobial host defense, wound healing, angiogenesis, and malignancy has become increasingly appreciated as the function of platelets in the pathophysiology of these processes has been defined. This review will consider the formation, release, and physiologic roles of α–granules with special emphasis on work performed over the last decade.

Keywords: α-granule, vesicle trafficking, endocytosis, secretion, hemostasis

Overview of platelet α–granules

Platelets are anucleate, discoid shaped blood cells that serve a critical function in hemostasis and other aspects of host defense. These cells are replete with secretory granules, which are critical to normal platelet function. Among the three types of platelet secretory granules – α–granules, dense granules, and lysosomes - the α–granule is the most abundant. There are approximately 50–80 α–granules per platelet, ranging in size from 200–500 nm.1 They comprise roughly 10% of the platelet volume, 10-fold more than dense granules. The total α–granule membrane surface area per platelet is 14 μm2, ~8-fold more than dense granules and approximately equal to that of the open canalicular system (OCS),1 an elaborate system of tunneling invaginations of the cell membrane unique to the platelet.2 The extra membrane provided by the OCS and α–granules enables the platelet to increase its surface area by 2–4-fold upon platelet stimulation and/or spreading.

Morphologic features observed by electron microscopy have historically defined α–granules. They include 1) the peripheral membrane of the granule, 2) an electron dense nucleoid that contains chemokines and proteoglycan, 3) a less electron dense area adjacent to the nucleoid that contains fibrinogen, and 4) a peripheral electronluscent zone that contains von Willebrand factor (vWf).3 Not all zones, however, need to be observed in order to positively identify an α–granule. α–Granules have also been identified based on immunofluorescence studies. Staining of granule constituents such as P-selectin, vWf, and/or fibrinogen or other established markers identifies α–granules by this technique. However, α–granules appear to be heterogeneous with regard to cargo.4,5 Absence of a particular α–granule marker does not preclude classification of a vesicular structure as an α–granule. Thus, the definition of α–granules may yet undergo further refinement as we learn more about their formation, structure, and content.

Formation of α–granules

Vesicle trafficking

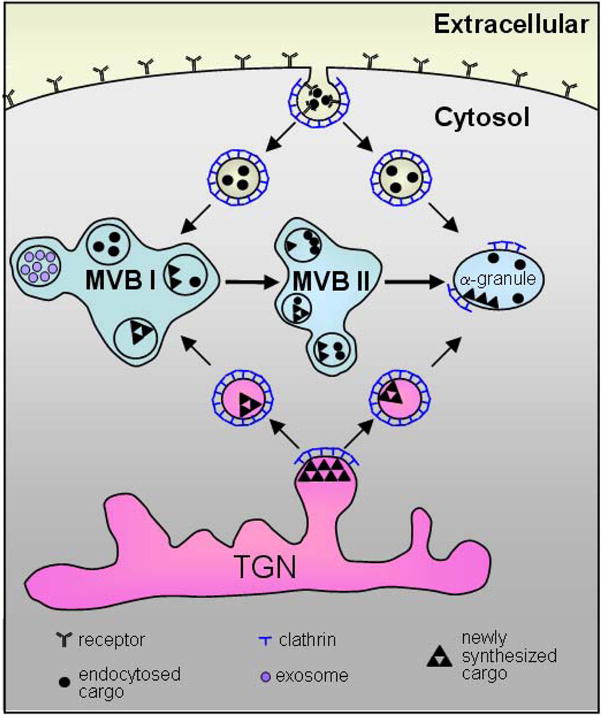

The development of α–granules begins in the megakaryocyte, but continues in the circulating platelet. In the megakaryocyte, α–granules are derived in part from budding of small vesicles containing α–granule cargo from the trans-Golgi network (Fig. 1).6,7 In other cell models, an orchestrated assemblage of coat proteins (e.g., clathrin, COPII), adaptor proteins (e.g., AP-1, AP-2, AP-3), fusion machinery (e.g., soluble NSF attachment protein receptors [SNAREs]), and monomeric GTPases (e.g., Rabs) mediate vesicle trafficking and maturation. Clathrin coat assembly likely functions, too, in trafficking of vesicles from the trans-Golgi network to α–granules in megakaryocytes. The clathrin-associated adaptor proteins AP-1, AP-2, and AP-3 are found in platelets8,9 and are proposed to function in clathrin-mediated vesicle formation in platelets.10 Mutations in the gene encoding AP-3, for example, results in impaired dense granule formation.9 Clathrin-mediated endocytosis also functions in the delivery of plasma membrane into α–granules (Fig. 1). Vesicles budding off from either the trans-Golgi network or the plasma membrane can subsequently be directed to multivesicular bodies (MVBs).

Figure 1. Working model of α–granule formation in megakaryocytes.

α–Granule cargo derives from budding of the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and endocytosis of the plasma membrane. Both processes are clathrin-mediated. Receptor-mediated endocytosis is depicted in this figure; however, pinocytosis of α–granule cargo can also occur. Vesicles can subsequently be delivered to multivesicular bodies (MVBs), where sorting of vesicles occurs. It is possible that vesicles may also be delivered directly to α–granules. Some vesicles within MVBs contain exosomes. MVBs can mature to become α–granules.

MVBs found in most cells are endosomal structures containing vesicles that form from the limiting membrane of the endosome.11,12 They are typically transient structures involved in sorting vesicles containing endocytosed and newly synthesized proteins. In megakaryocytes, MVBs serve in an intermediate stage of granule production.13 Both dense granules and α–granules are sorted by MVBs.13,14 Vesicles budding from the trans-Golgi network may be delivered directly to MVBs (Fig. 1).13 Kinetic studies in megakaryocytes have demonstrated that transport of endocytosed proteins proceeds from endosomes to immature MVBs (MVB I, with internal vesicles alone) to mature MVBs (MVB II, with internal vesicles and an electron dense matrix) to α–granules. α–Granules within MVBs contain 30–70 nm vesicles, termed exosomes.13 Some exosomes persist in mature α–granules and are secreted following platelet activation.15 Although it is unknown whether all or most vesicle trafficking to α–granules proceeds through MVB, these observations indicate that MVB represent a developmental stage in α–granule maturation.

Maturation of α–granules continues in circulating platelets by endocytosis of platelet plasma membranes.16–18 A clathrin-dependent pathway leading to the delivery of plasma membrane to α–granules has been described, as has a clathrin-independent pathway that traffics vesicles to lysosomes.18 Unlike other cells, coated vesicles in platelets retain their clathrin coat throughout trafficking and for a period following fusion with α–granules.17 Platelet endocytosis appears to be a constitutive activity of resting platelets. The molecular control of endocytosis in platelets is not known, but may involve the Src family receptors Fyn, Fgr, Lck, and/or Lyn based on colocalization studies, their tyrosine-phosphorylation status,19,20 and evidence of a role for Src family receptors in lymphocyte endocytosis.21 Studies performed in dogs evaluating the accumulation of fibrinogen and immoglobulin, which are endocytosed by circulating platelets, show that levels of endocytosed, but not endogenous, α–granule proteins increase as platelets age.22 This observation confirms that constitutive trafficking to α–granules continues throughout the lifespan of the platelet.

Protein Sorting

Many α–granule proteins are produced by megakaryocytes and sorted to α–granules via a regulated secretory pathway. These proteins are synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum, exported to the Golgi for maturation, and subsequently sorted at the trans-Golgi network.23 Trafficking of some well-known α–granule proteins synthesized in megakaryocytes, such as P-selectin, has been evaluated. Initial studies in heterologous cells indicated that the sorting sequence for P-selectin is contained within its cytoplasmic tail.24–27 Subsequent studies, however, indicated that the cytoplasmic tail of P-selectin targets this adhesion molecule to storage granules in endothelial cells, but not in platelets.25,28 This observation demonstrates that while some principles of protein sorting can be generalized among cell types, the mechanism of sorting of a particular protein can vary between cell types.

Trafficking of soluble proteins has also been evaluated. Study of the targeting of CXCL4 (also known as platelet factor 4) to α–granules has led to the identification of a signal sequence responsible for sorting chemokines into α–granules.29,30 These experiments demonstrate that a four amino acid sequence within the exposed hydrophilic loop is required for sorting of CXCL4 into α–granules.30 An analogous sequence was identified in the platelet chemokines RANTES and NAP-2.30

Soluble proteins must be incorporated into vesicles formed at the trans-Golgi network to become cargo within mature α–granules. A mechanism involving binding to glycosaminoglycans has been proposed for sorting small soluble chemokines. Mice that lack the dominant platelet glycosaminoglycan, serglycin, fail to store soluble proteins containing basically charged regions, such as CXCL4, PDGF, or NAP-2, in their α–granules.31 This observation suggests that glycosaminoglycans may serve as a retention mechanism for chemokines possessing an exposed cationic region. A mechanism to incorporate larger soluble proteins into α–granules is by aggregation of protein monomers.32 Although not formally proven to sort by aggregation, large, self-assembling proteins such as multimerin have been proposed to sort into immature vesicles by homoaggregation.33 vWf self-assembles into large multivalent structures and is packaged into a discrete tubular structure within α–granules.34,35 Heterologous expression of vWf can drive the formation of granules in cell lines possessing a regulated secretory pathway (e.g., AtT-20, HEK293, or RIN 5F cells), but not in cells lines that lack such a pathway (CHO, COS, or 3T3 cells).36,37 While aggregation and glycosaminoglycan binding represent plausible mechanisms for sorting soluble proteins, alternative sorting receptors must exist for other endogenous α–granule proteins.

Plasma proteins are incorporated into α–granules via several distinct mechanisms of endocytosis. During receptor mediated endocytosis, a plasma protein is bound to a platelet surface receptor and subsequently internalized via a clathrin-dependent process. The most well-studied example is the incorporation of fibrinogen via integrin αIIbβ3.38–42 Plasma proteins such as immunoglobulins and albumin incorporate into α–granules via pinocytosis.43 The endocytosis of factor V by megakaryocytes involves two receptors. Following initial binding to a specific factor V receptor, subsequent binding to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1) occurs and clathrin-dependent mediated endocytosis ensues.44,45 Endocytosis of α–granule proteins may occur at the level of the megakaryocyte, the platelet, or both.

Transport of α–granules into platelets

α–Granules formed in megakaryocytes must be distributed to platelets during megakaryopoiesis. Two models to account for organelle delivery during megakaryopoiesis include the fragmentation model and the proplatelet model. The fragmentation model predicts that the megakaryocyte demarcation membrane system divides the cell into regions, each containing their allotment of organelles.46 The proplatelet model predicts that, in a profound terminal reorganization of the megakaryocyte, platelets form along extended projections termed proplatelets.47–49 Recent studies have indicated that platelets are produced in vivo via the formation of proplatelets50 and that α–granules are transported from megakaryocytes to α–granules on microtubule bundles.51 These studies demonstrate that organelles within the megakaryocyte move from the cell body to the nascent platelets on microtubule tracks, powered by the microtubule motor proteins. Organelles move at a rate of 0.1–2 μm/min in what appears to be a random direction. They are captured in developing platelets by virtue of microtubule coils, which persist in platelets.51

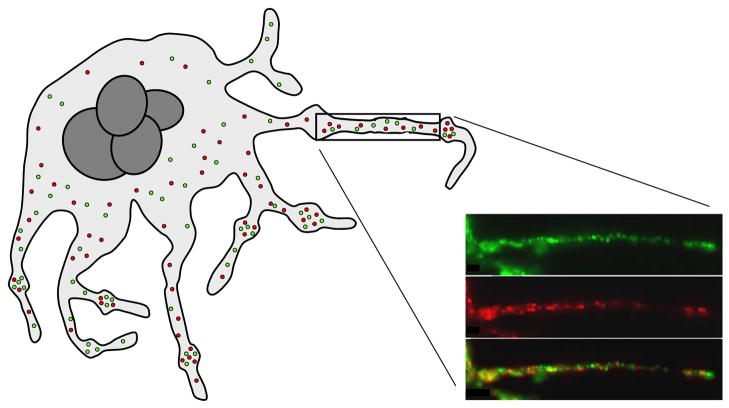

Individual granules that move along proplatelet microtubule tracks appear to be heterogeneous with regard to cargo (Fig. 2).4 Some α–granules stained with antibodies directed against vWf, but not fibrinogen. Others stained with antibodies against fibrinogen, but not vWf.4 Additional antigen pairs such as vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) and endostatin, as well as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and thrombospondin-1, were also found to reside in different α–granule subpopulations.4 Differential staining of α–granule subpopulations is observed in mature platelets as well.4,5 Whether different α–granule subpopulations represent α–granules derived from different sources (e.g., endocytosis versus regulated secretory pathway), differentially sorted in MVBs, or separated by yet unknown mechanisms remains to be determined.

Figure 2. Model of transport of α–granules during platelet formation.

Platelet α–granules are transported along microtubules from the megakaryocyte cell body through long pseudopodial extensions termed proplatelets. Platelets form as bulges along the length of these extensions. α–Granules are maintained in the nascent platelets by coiled microtubules. The insert demonstrates subpopulations of α–granules containing distinct cargos being transported along a proplatelet. α–Granules containing fibrinogen are shown in green, while those containing vWf are shown in red. (Insert from Italiano et al., Blood, 111:1227–1233.)

Defects in α–granule formation

Defects of α–granule formation have been described in both patients and mice. Gray platelet syndrome is the best known of the inherited disorders of α–granule formation (for review see 52). This syndrome is heterogenous and its genetic underpinnings have yet to be elucidated. α–Granules are also severely reduced in Medich giant platelet disorder and the White platelet syndrome.53,54 The molecular defects resulting in these syndromes, however, have not been identified.

α–Granule deficiency can result from mutations or deletions of specific transcription factors. For example, mice that lack Hzf, a zinc finger protein that acts as a a transcription factor, produce megakaryocytes and platelets with markedly reduced α–granules, mimicking Gray platelet syndrome.55 Fibrinogen, PDGF, and vWf are nearly absent from Hzf-deficient platelets. However, no mutations in the orthologous Hzf gene were identified in a series of patients with Gray platelet syndrome.56 Mutations in GATA1 have been described in patients with thrombocytopenia and markedly reduced or absent α–granules.57,58 The downstream regulators involved in granule formation, however, have not been characterized for these transcription factor mutants.

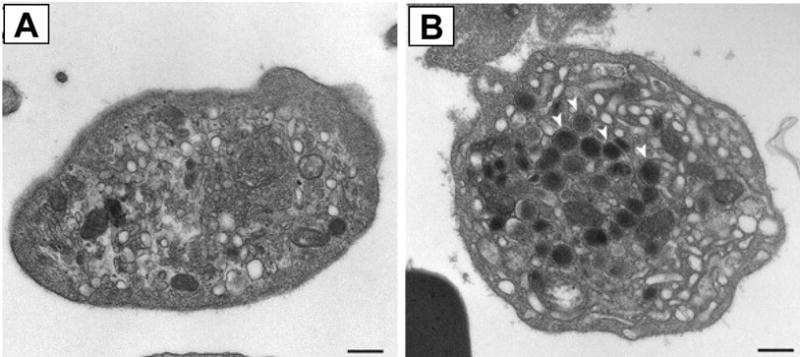

Some mutations resulting in markedly decreased or absent α–granules occur in genes encoding proteins involved in vesicular trafficking. ARC syndrome results from mutations in the VPS33B gene.59,60 VPS33B is a membrane-associated protein that binds tightly to and regulates the function of SNAREs.60 VPS33B associates with α–granules in platelets.59 Patients with this mutation possess α–granule-deficient platelets (Fig. 3), and their platelets possess no detectable PF4, vWf, fibrinogen, nor P-selectin.59 This observation indicates that loss of VPS33B effects incorporation of both endogenous and endocytosed proteins, as well as both soluble and membrane-bound proteins, into α–granules.59 The number of dense granules in VPS33B-deficient platelets is somewhat increased, indicating that VPS33B function is not critical for dense granule formation. Isolated deficiencies of dense granule formation with normal α-granule formation, such as in the Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome, are well-described. These observations further support the premise that dense granule and α–granule formation require distinct membrane trafficking machineries.

Figure 3. Absence of α–granules in platelets from patients harboring a mutation in VPS33B.

Thin-section transmission electron micrographs of platelets (A) from a fetus with a mutation in VPS33B and (B) platelets from an unaffected fetus. Abundant α–granules indicated with white arrows in control platelets are lacking in platelets with mutant VSP33B. Bar, 500 nm. (Adapted from Lo et al., Blood, 106:4159–4166).

That said, some mutations in vesicle trafficking proteins result in defects in both dense granule and α–granule formation, indicating aspects of commonality between the two pathways. Gunmetal mice with a mutant Rab geranylgeranyl transferase demonstrate a macrothrombocytopenia with a significant defect in both α–granule and dense granule production.61,62 While the substrates of Rab geranylgeranyl transferase involved in granule formation have not all been elucidated, Rab27 is hypoprenylated in gunmetal mice and associates with both α–granules and dense granules.61,63,64 Rab27 is a small GTP binding protein that regulates membrane trafficking.65 Mice deficient in Rab27b demonstrate reduced numbers of α–granules and dense granules in their megakaryocytes and impaired proplatelet formation.63 These observations suggest that Rab27b may coordinate proplatelet formation with granule transport. Other Rab proteins, including Rabs 1a, 1b, 3b, 5a, 5c 6a, 7, 8, 10, 11a 14, 18, 21, 27a, 27b, 32, 37 are present in platelets, associated with membranes, and may function in membrane trafficking and granule formation.8,66

Defects in membrane composition can also result in aberrant α–granule formation. Mice lacking the ATP-binding cassette half-transporter, ABCG5, suffer sitosterolemia, an accumulation of circulating plant sterols, and a macrothrombocytopenia characterized by large platelets with decreased granules.67 Sitosterolemia secondary to ABCG5 deficiency also occurs in humans and results in macrothrombocytopenia.68 The reason why the megakaryocyte membrane system is more sensitive than other cells to plant sterols is unknown. However, the observation that α–granule formation is impaired in this condition may inform strategies for studying how α–granule membranes form.

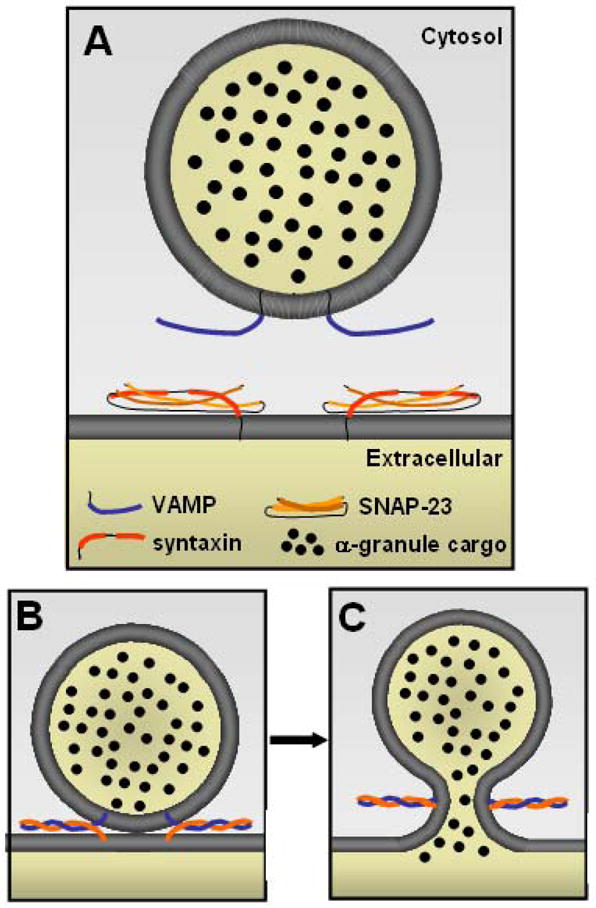

Molecular mechanisms of α–granule release

α–Granule contents must be released from their intracellular repository in order to achieve their physiologic function. α–Granule contents are release when the α–granule membrane fuses with surface-connected membranes of the OCS or the plasma membrane.69 SNAREs represent the core of the fusion machinery. They are membrane-associated proteins that are oriented to the cytosol (Fig. 4). SNAREs associated with granules are termed vesicular SNAREs (vSNAREs), while those associated with target membranes (e.g., OCS and plasma membrane) are termed tSNAREs. The association of vSNAREs with tSNAREs generates the energy required for membrane fusion.70

Figure 4. Role of SNAREs α–granule membrane fusion.

A) The primary vSNARE mediating platelet α–granule secretion is VAMP-8, with VAMP-3 and perhaps VAMP-2 serving subordinate functions. Platelet tSNAREs include syntaxins and SNAP-23. Syntaxin-2 and 4 participate in α–granule release. Coiled-coil domains (bolded) within vSNAREs (blue) and tSNAREs (orange) interact, forming a twisted 4-helical bundle. B) Interaction of the coiled-coil domains brings the opposing membranes of the granule and target membrane into close apposition. C) Binding of vSNAREs and tSNAREs generates energy required for membrane fusion. Pore formation with release of granule contents subsequently ensues.

Known platelet vSNAREs include VAMP-2, -3, -7, and -8; while known platelet tSNAREs include syntaxins 2, 4, 7, and 11 and SNAP-23, -25, and -29.71–77 Studies performed in mice deficient in specific VAMP isoforms indicate that VAMP-8 is the dominant vSNARE involved in α–granule release, while VAMP-3 and perhaps VAMP-2 play subordinate roles.76,78 Syntaxins 2 and 4 both appear to function in α–granule release, which is unusual in that two syntaxin isoforms do not typically mediate release of the same granule.72,79 There is no indication that SNAP-25 or SNAP-29 function in α–granule release, while the function of SNAP-23 is well-established.72,79,80 The distribution of SNAREs in platelets provides a basis for several characteristics of α–granule secretion, including homotypic α–granule fusion and the fusion of α–granules with the open canalicular system and plasma membrane.81 In addition to their roles in α–granule release, SNAREs likely participate in platelet granule formation. However, this SNARE function yet to be evaluated in detail.

The function of SNAREs in platelet granule secretion must be tightly regulated so as to prevent the indiscriminant release of α–granule cargo. The (Sec1/Munc) SM proteins function as clamps to regulate the function of SNAREs. SM protein isoforms found in platelets include Munc13-4 and Munc18a, b, and c. Of these, Munc18c has been found to function in α–granule release.82 Munc-18c is complexed primarily to syntaxin-4 in platelets.82 An antibody that prevents association of Munc-18c with syntaxin-4 augments α–granule release, raising the possibility that Munc18c serves as a negative regulatory of SNARE function.82 Munc13-4 functions in dense granule release as a downstream effector of Rab27;83 however, its role in α–granule release is not known. CDCrel-1 is another syntaxin binding protein implicated in the regulation of α–granule release. Platelets from mice lacking CDCrel-1 demonstrate enhanced secretion in response to collagen.84

Many other chaperone proteins that bind to and direct the function of SNARE proteins have been described. A subset of these proteins has been found in platelets, and some of these function in α–granule secretion. NSF is a hexameric ATPase that is essential for most forms of membrane-trafficking, including regulated granule secretion.85 The primary role of NSF is to disassemble SNARE complexes present on the same membrane (cis conformation) so that they are available to interact with cognate SNAREs on opposing membranes (trans conformation). Both inhibitory peptides and antibodies to NSF have been demonstrated to interfere with α–granule release from platelets.79,86 Further evidence suggests that nitric oxide inhibits NSF regulation of α–granule release.87 The soluble NSF-attachement protein (SNAP) α–SNAP binds and activates NSF.88 In platelets, wild-type α–SNAP augments granule secretion, whereas a dominant-negative α–SNAP mutant (α–SNAPL294A) and antibodies directed at α–SNAP inhibit granule secretion.

Rab proteins and their effectors are capable of docking opposing membranes and seem to modify SNARE protein function. Rab proteins are the largest branch of the ras superfamily of GTPases. Rabs 3b, 6c, and 8 are phosphorylated upon platelet activation.66,89 Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor (RabGDI), a general inhibitor of RabGTPases, inhibits α–granule but not dense granule release.90 In addition, a dominant-negative mutant of His-tagged Rab4S22N (but not mutant His-Rab3BT36N) inhibits α–granule secretion but fails to affect dense granule release.90 These data raise the possibility that Rab 4 is required for α–granule but not dense granule secretion. In nucleated cells, Rab proteins have been shown to function by binding to large effector proteins that have been proposed to interact with SNARE proteins directly or with proteins, such as NSF and Munc-18c, which mediate SNARE protein function91 The Rab effector proteins in platelets that mediate α–granule release have not yet been identified.

Platelet α–granules content

α–Granule function derives from their contents. The content of α–granules includes both membrane bound proteins that become expressed on the platelet surface and soluble proteins that are released into the extracellular space. Most membrane bound proteins are also present on the resting plasma membrane92 These proteins include integrins (e.g., αIIb, α6, β3), immunoglobulin family receptors (e.g. GPVI, Fc receptors, PECAM), leucine-rich repeat family receptors (e.g., GPIb-IX-V complex), tetraspanins (e.g., CD9) and other receptors (CD36, Glut-3)93–97 The abundance of plasma membrane receptors residing in α–granule membranes suggests that endocytosis of plasma membrane contributes to the presence of adhesion molecules in α–granules92 Not all membrane-associated α–granule proteins, however, are present on the plasma membrane (e.g., the integral membrane proteins fibrocystin L, CD109, P-selectin).93

Proteomic studies suggest that hundreds of soluble proteins are released by α–granules. It bears considering that proteins found in platelet releasate can originate from other platelet granules, cleavage of surface proteins, or exosomes. Nonetheless, the combination of proteomic studies evaluating releasate, isolated platelet α–granules, and isolated platelet dense granules provides creditable information regarding the identity of proteins released by α–granules.93,98–101 Many of the proteins found in α–granules are present in plasma. This observation raises the question of whether the α–granule counterparts of plasma proteins differ in structure or function. Also, while many important bioactive proteins are present, concentrated, and even modified in platelet α–granules, establishing the physiologic importance of a particular α–granular protein is challenging. Nonetheless, as discussed below, there is evidence that secreted α–granule proteins function in coagulation, inflammation, atherosclerosis, antimicrobial host defense, angiogenesis, wound repair, and malignancy.

Functional roles of platelet α-granules

Coagulation

Platelets secrete many mediators of blood coagulation. Whereas platelet dense granules contain high concentrations of low molecular weight compounds that potentiate platelet activation (e.g., ADP, serotonin, and calcium), α-granules concentrate large polypeptides that contribute to both primary and secondary hemostasis. α–Granules secrete fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor (vWf), adhesive proteins which mediate platelet-platelet and platelet-endothelial interactions. α-Granular vWf constitutes 20% of the total vWf protein and is enriched in high molecular weight forms.102,103 Studies in which normal bone marrow was transplanted into pigs with severe von Willebrand disease demonstrated that platelet vWf could partially compensate for lack of plasma vWf.104 In a separate study, gene transfer resulting in ectopic expression of vWf in liver of mice with severe vWD led to normal thrombus formation following vascular injury.105 These results suggest that α-granule vWf can contribute to, but is not necessary for, normal hemostasis and thrombus formation.

Adhesive receptors found in α-granules also participate in platelet adhesion. Components of the vWf receptor complex, GPIbα-IX-V, the major receptor for fibrinogen, integrin αIIbβ3, and the collagen receptor, GPVI, are found in α–granules.92,97 Although these receptors are constitutively expressed on the platelet plasma membrane, an estimated one-half to two-thirds of αIIbβ3 and one-third or more of GPVI reside in α-granule membranes in resting platelets and are expresssed following activation.94–97

Platelet α-granules contain a number of coagulation factors and co-factors which participate in secondary hemostasis. Factors V, XI, and XIII each localize in α-granules and are secreted upon platelet activation.106 Factor V is endocytosed from the plasma and is stored complexed to the carrier protein multimerin, while factors XI and XIII are endogenously synthesized in megakaryocytes.107–109 Some platelet-derived coagulation factors are structurally different from their plasma counterparts. In contrast to plasma pools, platelet-derived factor V is released in a partially activated form that exhibits substantial cofactor activity prior to thrombin activation.110 Purified platelet-derived factor V/Va is more resistant to inactivation by activated protein-C or Ser(692) phosphorylation than its plasma counterpart.111 Likewise, washed platelets from both normal and plasma factor XI-deficient donors correct the clotting defects observed in factor XI-deficient plasma.112 Platelet α-granules also contain the inactive precursor of thrombin, prothrombin, and significant stores of high molecular weight kininogens, which augment the intrinsic clotting cascade.93,106 In addition, platelets release inhibitory proteases, such plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and α2-antiplasmin, which limit plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis.106 Degradation of α–granule proteins by plasmin secondary to upregulation of urokinase plasminogen activator in megakaryocytic α–granules,113 as observed in the Quebec platelet disorder, results in a bleeding diathesis.114 Patients with Gray Platelet Syndrome lack α–granules and also present with a bleeding diathesis.52 These observations demonstrate a role for α–granule proteins in hemostasis.

Platelets also contribute to hemostatic balance by secreting numerous proteins that limit the progression of coagulation. α-Granules store antithrombin, which cleaves activated clotting factors in both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, and C1-inhibitor, which degrades plasma kallikrein, factor XIa, and factor XIIa. Platelets secrete tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI),115 protein S,116 and protease nexin-2 (amyloid β-A4 protein), which inhibits factors XIa and IXa.117 The anticoagulant properties of platelet-derived protease nexin-2 have been demonstrated in transgenic mouse models, as specific and modest overexpression of protease nexin-2 in platelets both reduces in vivo cerebral thrombosis and increases intracerebral hemorrhage.118 α-Granules store the proteinase plasmin and its inactive precursor plasminogen. The observation that α–granules are heterogenous and may be differentially released could explain how they contribute both anti- and pro-coagulants to regulate coagulation. However, the possibility that pro- and anticoagulants are separated into different populations and that these populations are differentially released has not been evaluated.

Inflammation

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that platelets contribute to the initiation and propagation of the inflammatory process.119 Platelet α–granules function in inflammation both by expressing receptors that facilitate adhesion of platelets with other vascular cells and by releasing a wide range of chemokines.

Adhesive interactions generally result in mutual activation and in the propagation of the inflammatory phenotype of each cell. Fibrinogen, fibronectin, vitronectin, and vWf, contribute to firm platelet-endothelial adhesion by forming cross-bridges between platelet GPIIb-IIIa and endothelial αVβ3 integrin or ICAM-1.120,121 However, although these proteins are found in α-granules, the specific contributions of platelet-, endothelial- and plasma-derived pools have not been established. P-selectin, which translocates from α-granules to the platelet surface membrane following platelet activation, participates in platelet interactions with endothelial cells, monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes 122,123. In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrate that platelets, regardless of their activation state, are able to transiently adhere to the intact, activated endothelium.124,125 These interactions are mediated by endothelial P-selectin binding to constitutively-expressed platelet P-selectin glycoprotein-1 (PSGL-1) or platelet GPIbα.124,126 Platelet-endothelial interactions are strengthened following platelet activation, as platelet P-selectin binds to endothelial PSGL-1.127 A recent study using intravital fluorescence microscopy demonstrates the importance of P-selectin and PSGL-1 in these interactions, as platelet adherence to an inflamed endothelial wall was significantly reduced following immunoneutralization of either P-selectin or PSGL-1.128

P-selectin also mediates platelet interactions with PSGL-1-expressing immune cells. Activated platelets bind to circulating immune cells in the blood stream, and surface-adherent platelets facilitate the recruitment, rolling, and arrest of monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes to the activated endothelium.123,129,130 Platelets have been shown to play a critical role in the recruitment of neutrophils to damaged lung capillaries. Platelet depletion, P-selectin neutralization, or selective knockout of P-selectin in the hematopoietic compartment reduces neutrophil recruitment and inhibits the development of acute lung injury.131,132 Adherence to platelets induces a host of proinflammatory responses in immune cells, including activation of adhesion receptor complexes, secretion of chemokines, cytokines, proteases, and pro-coagulants, and promotion of cellular differentiation.119 In platelets, these interactions promote further activation and granular secretion.

Platelet α–granules also influence inflammation by secreting high concentrations of proinflammatory and immune-modulating factors. These mediators induce recruitment, activation, chemokine secretion, and differentiation of other vascular and hematologic cells.133 In some cases, these chemokines feed back to stimulate chemokine receptors on the platelet surface, thereby causing platelet activation, secretion, and perpetuation of the inflammatory cycle. α-Granules contain a wide range of chemokines including CXCL1 (GRO-α), CXCL4, CXCL5 (ENA-78), CXCL7 (PBP, β-TG, CTAP-III, NAP-2), CXCL8 (IL-8), CXCL12 (SDF-1α), CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL3 (MIP-1α), and CCL5 (RANTES).133 Among these, CXCL4 and CXCL7 are the most abundant.134 For example, platelets contain 20 μg of CXCL4/109 cells, and following thrombin stimulation the serum concentration of CXCL4 rises to 5–10 μg/ml, approximately 1000-fold greater than normal plasma.135,136 Platelets are considered the major cellular source of CXCL4 and CXCL7, whereas platelet secretion of other chemokines is thought to merely augment their secretion by other cells.121 CXCL4 has been shown to induce neutrophil adhesion and degranulation, monocyte activation, and monocyte differentiation to macrophages and foam cells.137–139 In coordination with CCL5, CXCL4 is also able to induce adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells.140 The most abundant platelet-derived chemokine, CXCL7, can be sequentially and proteolytically cleaved to form four distinct chemokines – PBP, CTAP-III, β-TG, and NAP-2.134 It is only NAP-2, however, that is thought to display significant chemotactic activity.141 Numerous studies demonstrate that CXCL7 induces neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion to endothelial cells.134,142

Atherosclerosis

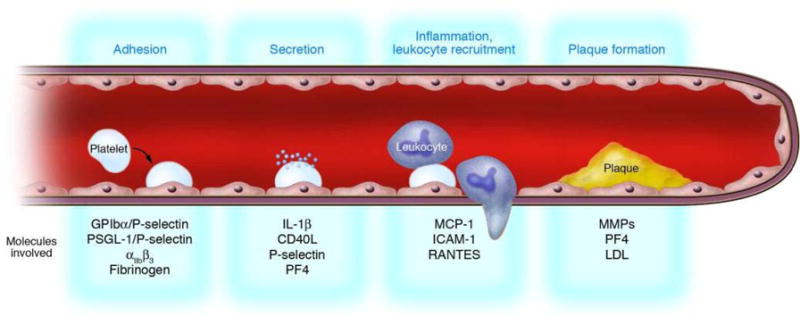

Atherosclerosis represents an important example of the role of platelet α–granule function in inflammation. Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the infiltration of immune cells into the subendothelial layers of the arterial wall (Fig. 5).127,143 Platelets are increasingly thought to play a central role in both the initiation and progression of the disease.144 Platelets influence atherogenesis by adhering to activated endothelial cells and depositing chemotactic mediators on the endothelial surface. Platelets also interact with leukocytes, facilitating their migration into the arterial wall.121 In multiple mouse models of atherosclerosis (LDL-receptor−/− and apolipoprotein E−/−), P-selectin deficiency is associated with decreased formation of fatty streaks and reduction in plaque lesion size.145,146 Specific knockout of platelet P-selectin reduces lesion development by 30% in apoE−/− mice. A subsequent study demonstrated that platelet, not endothelial, P-selectin is required for neointimal formation following vascular injury.147,148 In apoE−/− mice, injection of activated wild-type, but not P-selectin deficient, platelets increased monocyte arrest on atherosclerotic lesions and, subsequently, the size of the lesion.149 P-selectin has also been shown to be necessary for platelet deposition of CCL5 on inflamed and atherosclerotic endothelium.150

Figure 5. Hypothetical model of atherogenesis triggered by platelets.

Activated platelets roll along the endothelial monolayer via GPIbα/P-selectin or PSGL-1/P-selectin. Thereafter, platelets firmly adhere to vascular endothelium via β3 integrins, release proinflammatory compounds (IL-1β, CD40L), and induce a proatherogenic phenotype of ECs (chemotaxis, MCP-1; adhesion, ICAM-1). Subsequently, adherent platelets recruit circulating leukocytes, bind them, and inflame them by receptor interactions and paracrine pathways, thereby initiating leukocyte transmigration and foam cell formation. Thus, platelets provide the inflammatory basis for plaque formation before physically occluding the vessel by thrombosis upon plaque rupture. (Adapted from Gawaz et al., J. Clin. Invest., 115:3378).

CCL5 and other chemokines found in platelet α-granules, including CCL2, CCL3, CXCL4, and CXCL12, have been detected in atherosclerotic plaques. In mouse models, pharmacological inhibition or genetic mutation of these chemokines and/or their receptors decrease the progression of atherosclerosis.133,151–155 CXCL4-deficient, ApoE−/− mice show reduced lesion size.154 Disruption of proinflammatory interactions between CXCL4 and CCL5 inhibit atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice.151 Unlike CXCL4, however, which derives from platelets, many of these chemokines are secreted by multiple cell types. Functional studies directly assessing the contribution of platelet-derived chemokines to atherogenesis have been limited. Bone marrow reconstitution in chimeric mice and platelet-specific conditional knockouts will help define the direct contribution of α–granular chemokines to atherogenesis.121,156

Antimicrobial Host Defense

Although it was once thought that platelets promoted infection by facilitating the adhesion of microbes to the vessel wall, it is now understood that platelets play a significant role in host defense against pathogenic microorganisms.157,158 Numerous studies have demonstrated that platelets are among the first blood cells to recognize endothelium damaged by microbial colonization and to accumulate at sites of infected endovascular lesions.157,159–161 Platelets rapidly associate with vegetations in infective endocarditis and accrue at sites of suppurative thrombophlebitis.161 Platelets interact directly with viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protozoa.162–166 Recent studies, for example, have demonstrated that platelets bind to erythrocytes infected with plasmodium and kill the parasite.166

Platelet α-granules contain proteins with direct microbicidal properties, a group collectively referred to as platelet microbicidal proteins.121 Many of the chemokines secreted by activated platelets – including CXCL4, thymosin-β4, the derivatives of CXCL7 (PBP, CTAP-III, NAP-2), and CCL5 (RANTES) – are microbicidal.167,168 Truncation of CTAP-III and NAP-2 at their C-terminus generates two additional peptides, thrombocidins-1 and -2 (TC-1, TC-2), which are bactericidal in vitro against some strains of Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and fungicidal for Cryptococcus neoformans.169 In the setting of infective endocarditis, in vitro susceptibility of staphylococcal extracts to thrombocidin-1 correlated well with clinical severity and prognosis.170 Another microbicidal protein, thymosin-β4, localizes to platelet α-granules.168 While it is debatable whether the local concentration of these secreted proteins are more important for antimicrobial activity or chemoattraction of leukocytes, multiple studies using combined in vitro and in vivo techniques have demonstrated that platelets are clinically relevant to host defense.170–173

α–Granules also contain complement and complement binding proteins, which facilitate the clearance of microorganisms from the circulation. Platelet α-granules secrete complement C3 and complement C4 precursor, which participate in the complement activation cascade.93 P-selectin binds C3b, localizing the inflammatory response to sites of vascular injury.174 Platelets α–granules also contain regulators of complement activation, such as C1 inhibitor.175 Platelet factor H secreted from α–granules regulates C3 convertase in the alternative pathway.176 Despite these suggestive observations, the impact of α–granule deficiency on complement activation and regulation is not known.

Mitogenesis

Angiogenesis

That platelets support angiogenesis is well-established.177,178 However, the molecular mechanisms of this function are just beginning to be understood.179 Platelet α-granules contain a variety of both pro- and anti-angiogenic proteins. Growth factors stored in α-granules include vascular endothelium growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and insulin-like growth factor (IGF).106,180 These angiogenic activators collectively promote vessel wall permeability and recruitment, growth, and proliferation of endothelial cells and fibroblasts. Although these growth factors are secreted by a variety of inflammatory cells, the rapidity with which platelets accumulate at sites of vascular injury makes them a relevant source of mitogenic mediators. For example, VEGF concentrations are elevated 3-fold during the first minutes after plug formation following forearm incision.181 VEGF also accumulates inside platelet thrombi formed in vivo.182 Platelet-derived VEGF and FGF-2 exert trophic effects on cultured endothelial cells.183 In an ex vivo rat aortic ring model, platelet-derived VEGF, bFGF, and PDGF promote sprouting of new blood vessels.184 α-Granules contain other pro-angiogenic mediators, including angiopoietin, CXCL12 (SDF-1α), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1, -2, and -9). Platelet-derived CXCL12 has been reported to induce recruitment of CD34+ progenitor cells to arterial thrombi in vivo and promote differentiation of cultured CD34+ cells to endothelial progenitor cells.155,185

α–Granules also contain established inhibitors of angiogenesis. TSP-1, a major constituent of α-granules, acts as a potent inhibitor of endothelial cell proliferation and stimulates endothelial cell apoptosis.186 In vivo studies demonstrate that TSP-1 inhibits revascularization in a model of hind limb ischemia, while TSP-deficient mice show accelerated revascularization. The proangiogenic activity in TSP-deficient mice is directly related to increased platelet secretion of CXCL12.186 CXCL4 also displays antiangiogenic properties, likely by preventing VEGF binding to its cellular receptor and by interfering with the mitogenic effects of FGF.187,188 In a rat aortic ring model in which platelet-derived VEGF and FGF induced endothelial sprouting, immunoneutralization of CXCL4 in the releasate further amplified neovascularization.184 Platelet α-granules contain other anti-angiogenic proteins, including angiostatin, endostatin, and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs-1 and -4). Recent studies suggest anti-angiogenic proteins may be packaged in different α-granule subpopulations than pro-angiogenic proteins 4. There is some evidence that secretion of pro- versus anti-angiogenic stores may be agonist-specific.4,189

Wound Healing

Platelets promote wound healing in several in vitro and in vivo models.180 Although many of these studies and applications involve preparations that include platelets, isolated platelet supernatants enriched in α–granule proteins are sufficient to support wound healing. In vitro studies demonstrate that platelet releasate increases the proliferation and migration of osteogenic cells.190 Platelet releasate also stimulates proliferation of human tendon cells in culture and promotes significant synthesis of VEGF and HGF.191 Studies in dogs demonstrated that platelet releasate in a collagen sponge promotes periodontal tissue regeneration.192 Healing of cutaneous wounds is also promoted by platelet releasate in diabetic rats.193

Perhaps the strongest evidence that platelet releasate promotes wound healing is the use of “platelet-derived wound healing factor” (PDWHF) in the treatment of chronic wounds. PDWHF is a FDA-regulated preparation of the supernatant of washed, thrombin-stimulated platelets. This supernatant is added to microcrystalline collagen to generate PDWHF.194 In placebo controlled studies, PDWHF accelerated wound healing in the settings of chronic diabetic foot ulcers.195,196 PDWHF has also been used to treat leg ulcers in the setting of β-thalasemia intermedia.197 The mechanism by which PDWHF promotes healing remains largely unstudied; however, upregulation of αVβ3 in capilliaries surrounding treated, but not untreated wounds, has been observed.198 Not all studies using PDWHF have demonstrated a positive effect on wound healing compared to placebo.199 Differences in results may be secondary to differences in platelet concentrations used for preparations or different patient populations.

Malignancy

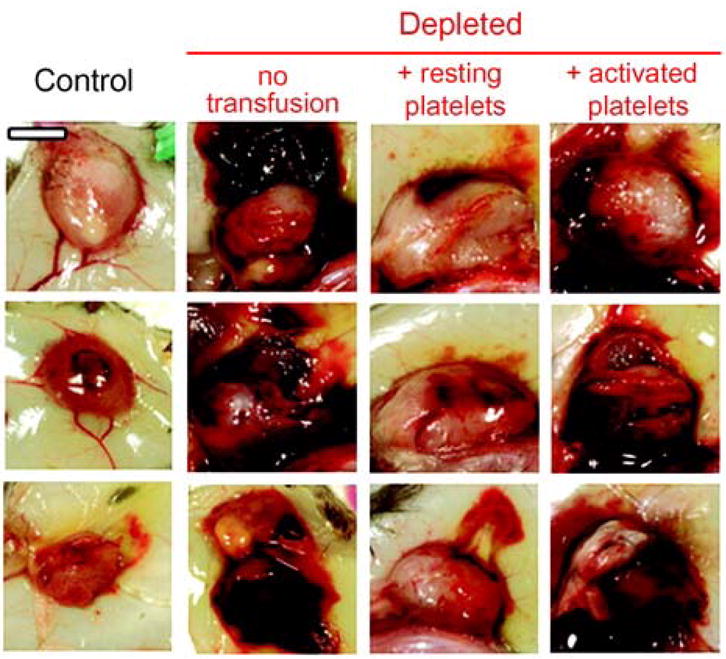

Platelets have been implicated in tumor stability, growth, and metastasis. Acute thrombocytopenia results in rapid tumor destabilization and intratumor hemorrhage.200 This observation implies an ongoing requirement for platelets in maintaining tumor stability. Infusion of resting, but not degranulated, platelets prevents thrombocytopenia-induced tumor bleeding (Fig. 6), suggesting that platelet granules contribute to tumor stability.200 Angiopoietin-1 may enhance intratumor stability in this model,200 however, the specific α–granule constituents that stabilize tumors remain to be identified.

Figure 6. Degranulated platelets are unable to prevent thrombocytopenia-induced tumor bleeding.

At day 8 after tumor cell implantation, mice were injected with either the control IgG (Control) or the platelet-depleting IgG (Depleted). A subset of mice was transfused 30 min before the induction of thrombocytopenia with tyrode buffer (no transfusion) or 7 × 108 of either resting or activated platelets and s.c. Lewis lung carcinoma cells were photographed 18 h later. Bar, 5 mm. (Adapted from Ho-Tin-Noe et al., Cancer Res, 68:6851–6858)

Primary tumors are highly dependent on the development of an adequate blood supply. As previously discussed, platelets contain both pro- and antiangiogenic factors and support angiogenesis. In animals bearing malignant tumors, platelets selectively accumulate angiogenesis regulators.201 In a canine model of cutaneous mast cell tumor, VEGF concentrations in activated platelet-rich plasma correlate well with microvascular density, mast cell density, and malignancy grading.202 Cancer patients have increased levels of serum VEGF and angiopoietin-1, which decrease after tumor resection.203–206 Platelet α-granules from cancer patients contain elevated levels of VEGF and angiopoietin-1207,205,208 and platelets constitute a significant source of circulating VEGF in cancer patients.209

Early evidence that platelets function in cancer progression derive from studies showing decreases in lung metastases following induction of thrombocytopenia.210–213 Platelet infusion reverses the effect on tumor metastasis. Adhesion of platelets to tumor cells is thought to facilitate tumor metastasis. Potential mechanisms by which platelet adhesion may facilitate tumor metastasis include cloaking tumor cells from immune surveillance and assisting their egress from the circulation.214,215 Adhesive proteins found in α-granules mediate direct interactions between tumors and platelets. P-selectin can mediate initial interactions by binding to mucins on the tumor surface.216 Global deficiency of P-selectin is associated with reduced tumor growth and metastasis, but specific knockout of platelet P-selectin has not been examined.217 Vitronectin and fibronectin in platelet releasate enhance the adhesion of tumor cells to cultured endothelial cells under shear in a αVβ3-dependent manner.218 In addition, platelet releasate can induce expression of tumor-proteases that enhance invasiveness.219 Future studies using platelet-specific knockouts of α-granule-derived mediators will enhance our understanding of the role of the platelet in angiogenesis and tumor metastasis.

Perspective

The diversity of physiologic functions influenced by platelets – coagulation, inflammation, microbial host defense, wound healing, and malignancy – raises the question how the platelet can modulate so many varied processes. Proteomic data cataloging individual α–granule proteins demonstrate that the α–granule possesses a wide array of bioactive proteins, implying participation of α–granule proteins in varied physiologic functions. The vast majority of these proteins, however, are also found in either plasma and/or other vascular cells, leaving the contribution of the α–granule source uncertain. Assessment of the α–granule pool of a specific protein in a given physiologic function will require bone marrow reconstitution in chimeric mice and/or platelet-specific conditional knockouts.

Evaluation of α–granule contents also demonstrates that α–granules contain many proteins with opposing activities: pro- and anticoagulants, proteases and their inhibitors, pro- and antiangiogenic proteins. To understand the role of α–granules in various physiologic functions, a more detailed understanding of how the activity of these contents is regulated is required. Do molar concentrations of various components dictate which activity is dominant? Is the activity of releasate regulated in a kinetic manner, with rapid onset of pro-coagulant or pro-angiogenic activities that are subsequently controlled by lagging inhibitory activities? Is the activity of these components regulated by differential release of heterogenous α–granule subpopulations?

An appreciation of the role of α–granule release in multiple physiologic functions raises the question of whether this activity can be controlled for therapeutic benefit. The observation that the biosynthetic pathway to dense granule and α–granule formation diverge at a relatively proximal step in granule formation suggests that α–granule formation could be specifically inhibited. Therapeutics that render platelets selectively deficient in either dense or α–granules could be useful in some clinical settings. Understanding the differential release of α–granules versus dense granules and, perhaps, differential release of distinct α–granule subpopulations may also inform strategies of controlling α–granule participation in disease processes. A more detailed understanding of the role of α–granules in disease states will be required for optimally targeting such strategies to specific disease entities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH HL87203 (R.F.) and T32 HL07917 (P.B.) and an Established Investigator Award from the American Heart Association (R.F.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Frojmovic MM, Milton JG. Human platelet size, shape, and related functions in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 1982;62:185–261. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1982.62.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White JG, Clawson CC. The surface-connected canalicular system of blood platelets--a fenestrated membrane system. Am J Pathol. 1980;101:353–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison P, Cramer EM. Platelet alpha-granules. Blood Rev. 1993;7:52–62. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(93)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Italiano JE, Jr, Richardson JL, Patel-Hett S, et al. Angiogenesis is regulated by a novel mechanism: pro- and antiangiogenic proteins are organized into separate platelet {alpha} granules and differentially released. Blood. 2008;111:1227–1233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sehgal S, Storrie B. Evidence that differential packaging of the major platelet granule proteins von Willebrand factor and fibrinogen can support their differential release. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2009–2016. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer EM, Harrison P, Savidge GF, et al. Uncoordinated expression of alpha-granule proteins in human megakaryocytes. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;356:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hegyi E, Heilbrun LK, Nakeff A. Immunogold probing of platelet factor 4 in different ploidy classes of rat megakaryocytes sorted by flow cytometry. Exp Hematol. 1990;18:789–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moebius J, Zahedi RP, Lewandrowski U, Berger C, Walter U, Sickmann A. The human platelet membrane proteome reveals several new potential membrane proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1754–1761. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500209-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li W, Rusiniak ME, Chintala S, Gautam R, Novak EK, Swank RT. Murine Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome genes: regulators of lysosome-related organelles. Bioessays. 2004;26:616–628. doi: 10.1002/bies.20042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King SM, Reed GL. Development of platelet secretory granules. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s1084952102000599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piper RC, Katzmann DJ. Biogenesis and function of multivesicular bodies. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:519–547. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodman PG, Futter CE. Multivesicular bodies: co-ordinated progression to maturity. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heijnen HF, Debili N, Vainchencker W, Breton-Gorius J, Geuze HJ, Sixma JJ. Multivesicular bodies are an intermediate stage in the formation of platelet alpha-granules. Blood. 1998;91:2313–2325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Youssefian T, Cramer EM. Megakaryocyte dense granule components are sorted in multivesicular bodies. Blood. 2000;95:4004–4007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heijnen HF, Schiel AE, Fijnheer R, Geuze HJ, Sixma JJ. Activated platelets release two types of membrane vesicles: microvesicles by surface shedding and exosomes derived from exocytosis of multivesicular bodies and alpha-granules. Blood. 1999;94:3791–3799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zucker-Franklin D. Endocytosis by human platelets: metabolic and freeze-fracture studies. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:706–715. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.3.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behnke O. Coated pits and vesicles transfer plasma components to platelet granules. Thromb Haemost. 1989;62:718–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behnke O. Degrading and non-degrading pathways in fluid-phase (non-adsorptive) endocytosis in human blood platelets. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1992;24:169–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stenberg PE, Pestina TI, Barrie RJ, Jackson CW. The Src family kinases, Fgr, Fyn, Lck, and Lyn, colocalize with coated membranes in platelets. Blood. 1997;89:2384–2393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pestina TI, Stenberg PE, Druker BJ, et al. Identification of the Src family kinases, Lck and Fgr in platelets. Their tyrosine phosphorylation status and subcellular distribution compared with other Src family members. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:3278–3285. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panigada M, Porcellini S, Barbier E, et al. Constitutive endocytosis and degradation of the pre-T cell receptor. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1585–1597. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heilmann E, Hynes LA, Friese P, George IN, Burstein SA, Dale GL. Dog platelets accumulate intracellular fibrinogen as they age. J Cell Physiol. 1994;161:23–30. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041610104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cramer EM, Debili N, Martin JF, et al. Uncoordinated expression of fibrinogen compared with thrombospondin and von Willebrand factor in maturing human megakaryocytes. Blood. 1989;73:1123–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koedam JA, Cramer EM, Briend E, Furie B, Furie BC, Wagner DD. P-selectin, a granule membrane protein of platelets and endothelial cells, follows the regulated secretory pathway in AtT-20 cells. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:617–625. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.3.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daugherty BL, Straley KS, Sanders JM, et al. AP-3 adaptor functions in targeting P-selectin to secretory granules in endothelial cells. Traffic. 2001;2:406–413. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.002006406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Disdier M, Morrissey JH, Fugate RD, Bainton DF, McEver RP. Cytoplasmic domain of P-selectin (CD62) contains the signal for sorting into the regulated secretory pathway. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:309–321. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green SA, Setiadi H, McEver RP, Kelly RB. The cytoplasmic domain of P-selectin contains a sorting determinant that mediates rapid degradation in lysosomes. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:435–448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartwell DW, Mayadas TN, Berger G, et al. Role of P-selectin cytoplasmic domain in granular targeting in vivo and in early inflammatory responses. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1129–1141. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.4.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briquet-Laugier V, Lavenu-Bombled C, Schmitt A, et al. Probing platelet factor 4 alpha-granule targeting. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:2231–2240. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Golli N, Issertial O, Rosa JP, Briquet-Laugier V. Evidence for a granule targeting sequence within platelet factor 4. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30329–30335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woulfe DS, Lilliendahl JK, August S, et al. Serglycin proteoglycan deletion induces defects in platelet aggregation and thrombus formation in mice. Blood. 2008;111:3458–3467. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tooze SA, Martens GJ, Huttner WB. Secretory granule biogenesis: rafting to the SNARE. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:116–122. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01907-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayward CP, Song Z, Zheng S, et al. Multimerin processing by cells with and without pathways for regulated protein secretion. Blood. 1999;94:1337–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cramer EM, Meyer D, le Menn R, Breton-Gorius J. Eccentric localization of von Willebrand factor in an internal structure of platelet alpha-granule resembling that of Weibel-Palade bodies. Blood. 1985;66:710–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang RH, Wang Y, Roth R, et al. Assembly of Weibel-Palade body-like tubules from N-terminal domains of von Willebrand factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:482–487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710079105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blagoveshchenskaya AD, Hannah MJ, Allen S, Cutler DF. Selective and signal-dependent recruitment of membrane proteins to secretory granules formed by heterologously expressed von Willebrand factor. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1582–1593. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-09-0462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner DD, Saffaripour S, Bonfanti R, et al. Induction of specific storage organelles by von Willebrand factor propolypeptide. Cell. 1991;64:403–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90648-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Handagama P, Scarborough RM, Shuman MA, Bainton DF. Endocytosis of fibrinogen into megakaryocyte and platelet alpha-granules is mediated by alpha IIb beta 3 (glycoprotein IIb-IIIa) Blood. 1993;82:135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Handagama P, Bainton DF, Jacques Y, Conn MT, Lazarus RA, Shuman MA. Kistrin, an integrin antagonist, blocks endocytosis of fibrinogen into guinea pig megakaryocyte and platelet alpha-granules. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:193–200. doi: 10.1172/JCI116170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Handagama PJ, Amrani DL, Shuman MA. Endocytosis of fibrinogen into hamster megakaryocyte alpha granules is dependent on a dimeric gamma A configuration. Blood. 1995;85:1790–1795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Handagama PJ, Shuman MA, Bainton DF. Incorporation of intravenously injected albumin, immunoglobulin G, and fibrinogen in guinea pig megakaryocyte granules. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:73–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI114173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Handagama PJ, George JN, Shuman MA, McEver RP, Bainton DF. Incorporation of a circulating protein into megakaryocyte and platelet granules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:861–865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.3.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.George JN, Saucerman S. Platelet IgG, IgA, IgM, and albumin: correlation of platelet and plasma concentrations in normal subjects and in patients with ITP or dysproteinemia. Blood. 1988;72:362–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bouchard BA, Meisler NT, Nesheim ME, Liu CX, Strickland DK, Tracy PB. A unique function for LRP-1: a component of a two-receptor system mediating specific endocytosis of plasma-derived factor V by megakaryocytes. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:638–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bouchard BA, Williams JL, Meisler NT, Long MW, Tracy PB. Endocytosis of plasma-derived factor V by megakaryocytes occurs via a clathrin-dependent, specific membrane binding event. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:541–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tavassoli M. Fusion-fission reorganization of membrane: a developing membrane model for thrombocytogenesis in megakaryocytes. Blood Cells. 1979;5:89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Italiano JE, Jr, Lecine P, Shivdasani RA, Hartwig JH. Blood platelets are assembled principally at the ends of proplatelet processes produced by differentiated megakaryocytes. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1299–1312. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel SR, Hartwig JH, Italiano JE., Jr The biogenesis of platelets from megakaryocyte proplatelets. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3348–3354. doi: 10.1172/JCI26891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Handagama P, Jain NC, Kono CS, Feldman BF. Scanning electron microscopic studies of megakaryocytes and platelet formation in the dog and rat. Am J Vet Res. 1986;47:2454–2460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Junt T, Schulze H, Chen Z, et al. Dynamic visualization of thrombopoiesis within bone marrow. Science. 2007;317:1767–1770. doi: 10.1126/science.1146304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richardson JL, Shivdasani RA, Boers C, Hartwig JH, Italiano JE., Jr Mechanisms of organelle transport and capture along proplatelets during platelet production. Blood. 2005;106:4066–4075. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nurden AT, Nurden P. The gray platelet syndrome: clinical spectrum of the disease. Blood Rev. 2007;21:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White JG. Medich giant platelet disorder: a unique alpha granule deficiency I. Structural abnormalities. Platelets. 2004;15:345–353. doi: 10.1080/0953710042000236512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White JG, Key NS, King RA, Vercellotti GM. The White platelet syndrome: a new autosomal dominant platelet disorder. Platelets. 2004;15:173–184. doi: 10.1080/09537100410001682805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kimura Y, Hart A, Hirashima M, et al. Zinc finger protein, Hzf, is required for megakaryocyte development and hemostasis. J Exp Med. 2002;195:941–952. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benit L, Cramer EM, Masse JM, Dusanter-Fourt I, Favier R. Molecular study of the hematopoietic zinc finger gene in three unrelated families with gray platelet syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2077–2080. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Balduini CL, Pecci A, Loffredo G, et al. Effects of the R216Q mutation of GATA-1 on erythropoiesis and megakaryocytopoiesis. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:129–140. doi: 10.1160/TH03-05-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tubman VN, Levine JE, Campagna DR, et al. X-linked gray platelet syndrome due to a GATA1 Arg216Gln mutation. Blood. 2007;109:3297–3299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lo B, Li L, Gissen P, et al. Requirement of VPS33B, a member of the Sec1/Munc18 protein family, in megakaryocyte and platelet alpha-granule biogenesis. Blood. 2005;106:4159–4166. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gissen P, Johnson CA, Morgan NV, et al. Mutations in VPS33B, encoding a regulator of SNARE-dependent membrane fusion, cause arthrogryposis-renal dysfunction-cholestasis (ARC) syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:400–404. doi: 10.1038/ng1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Detter JC, Zhang Q, Mules EH, et al. Rab geranylgeranyl transferase alpha mutation in the gunmetal mouse reduces Rab prenylation and platelet synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4144–4149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080517697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swank RT, Jiang SY, Reddington M, et al. Inherited abnormalities in platelet organelles and platelet formation and associated altered expression of low molecular weight guanosine triphosphate-binding proteins in the mouse pigment mutant gunmetal. Blood. 1993;81:2626–2635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tiwari S, Italiano JE, Jr, Barral DC, et al. A role for Rab27b in NF-E2-dependent pathways of platelet formation. Blood. 2003;102:3970–3979. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.TheBarral DC, Ramalho JS, Anders R, et al. Functional redundancy of Rab27 proteins and the pathogenesis of Griscelli syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:247–257. doi: 10.1172/JCI15058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fukuda M. Versatile role of Rab27 in membrane trafficking: focus on the Rab27 effector families. J Biochem. 2005;137:9–16. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Karniguian A, Zahraoui A, Tavitian A. Identification of small GTP-binding rab proteins in human platelets: thrombin-induced phosphorylation of rab3B, rab6, and rab8 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7647–7651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kruit JK, Drayer AL, Bloks VW, et al. Plant sterols cause macrothrombocytopenia in a mouse model of sitosterolemia. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6281–6287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rees DC, Iolascon A, Carella M, et al. Stomatocytic haemolysis and macrothrombocytopenia (Mediterranean stomatocytosis/macrothrombocytopenia) is the haematological presentation of phytosterolaemia. Br J Haematol. 2005;130:297–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Flaumenhaft R. Molecular basis of platelet granule secretion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1152–1160. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000075965.88456.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sudhof TC, Rothman JE. Membrane fusion: grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science. 2009;323:474–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1161748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lemons PP, Chen D, Bernstein AM, Bennett MK, Whiteheart SW. Regulated secretion in platelets: identification of elements of the platelet exocytosis machinery. Blood. 1997;90:1490–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Flaumenhaft R, Croce K, Chen E, Furie B, Furie BC. Proteins of the exocytotic core complex mediate platelet alpha-granule secretion. Roles of vesicle-associated membrane protein, SNAP-23, and syntaxin 4. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2492–2501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bernstein AM, Whiteheart SW. Identification of a cellubrevin/vesicle associated membrane protein 3 homologue in human platelets. Blood. 1999;93:571–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Polgar J, Chung SH, Reed GL. Vesicle-associated membrane protein 3 (VAMP-3) and VAMP-8 are present in human platelets and are required for granule secretion. Blood. 2002;100:1081–1083. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Polgar J, Lane WS, Chung SH, Houng AK, Reed GL. Phosphorylation of SNAP-23 in activated human platelets. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44369–44376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ren Q, Barber HK, Crawford GL, et al. Endobrevin/VAMP-8 is the primary v-SNARE for the platelet release reaction. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:24–33. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen D, Bernstein AM, Lemons PP, Whiteheart SW. Molecular mechanisms of platelet exocytosis: role of SNAP-23 and syntaxin 2 in dense core granule release. Blood. 2000 Feb 1;95:921–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schraw TD, Rutledge TW, Crawford GL, et al. Granule stores from cellubrevin/VAMP-3 null mouse platelets exhibit normal stimulus-induced release. Blood. 2003;8:8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lemons PP, Chen D, Whiteheart SW. Molecular mechanisms of platelet exocytosis: requirements for alpha-granule release. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;267:875–880. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lai KC, Flaumenhaft R. SNARE protein degradation upon platelet activation: Calpain cleaves SNAP-23. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194:206–214. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Feng D, Crane K, Rozenvayn N, Dvorak AM, Flaumenhaft R. Subcellular distribution of 3 functional SNARE proteins: Human cellubrevin, SNAP-23, and Syntaxin 2. Blood. 2002;99:4006–4014. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Houng A, Polgar J, Reed GL. Munc18-syntaxin complexes and exocytosis in human platelets. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19627–19633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shirakawa R, Higashi T, Tabuchi A, et al. Munc13–4 is a GTP-Rab27-binding protein regulating dense core granule secretion in platelets. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10730–10737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309426200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dent J, Kato K, Peng XR, et al. A prototypic platelet septin and its participation in secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3064–3069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052715199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Whiteheart SW, Schraw T, Matveeva EA. N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor (NSF) structure and function. Int Rev Cytol. 2001;207:71–112. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)07003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Polgar J, Reed GL. A critical role for N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein (NSF) in platelet granule secretion. Blood. 1999;94:1313–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Morrell CN, Matsushita K, Chiles K, et al. Regulation of platelet granule exocytosis by S-nitrosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3782–3787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408310102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clary DO, Griff IC, Rothman JE. SNAPs, a family of NSF attachment proteins involved in intracellular membrane fusion in animals and yeast. Cell. 1990;61:709–721. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90482-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fitzgerald ML, Reed GL. Rab6 is phosphorylated in thrombin-activated platelets by a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism: effects on GTP/GDP binding and cellular distribution. Biochem J. 1999;342:353–360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shirakawa R, Yoshioka A, Horiuchi H, Nishioka H, Tabuchi A, Kita T. Small GTPase rab4 regulates Ca2+-induced alpha -granule secretion in platelets. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33844–33849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zerial M, McBride H. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:107–117. doi: 10.1038/35052055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Berger G, Masse JM, Cramer EM. Alpha-granule membrane mirrors the platelet plasma membrane and contains the glycoproteins Ib, IX, and V. Blood. 1996;87:1385–1395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Maynard DM, Heijnen HF, Horne MK, White JG, Gahl WA. Proteomic analysis of platelet alpha-granules using mass spectrometry. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1945–1955. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Niiya K, Hodson E, Bader R, et al. Increased surface expression of the membrane glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex induced by platelet activation. Relationship to the binding of fibrinogen and platelet aggregation. Blood. 1987;70:475–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Berger G, Caen JP, Berndt MC, Cramer EM. Ultrastructural demonstration of CD36 in the alpha-granule membrane of human platelets and megakaryocytes. Blood. 1993;82:3034–3044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nurden P, Jandrot-Perrus M, Combrie R, et al. Severe deficiency of glycoprotein VI in a patient with gray platelet syndrome. Blood. 2004;104:107–114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Suzuki H, Murasaki K, Kodama K, Takayama H. Intracellular localization of glycoprotein VI in human platelets and its surface expression upon activation. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:904–912. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Piersma SR, Broxterman HJ, Kapci M, et al. Proteomics of the TRAP-induced platelet releasate. J Proteomics. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hernandez-Ruiz L, Valverde F, Jimenez-Nunez MD, et al. Organellar proteomics of human platelet dense granules reveals that 14-3-3zeta is a granule protein related to atherosclerosis. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:4449–4457. doi: 10.1021/pr070380o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Coppinger JA, Cagney G, Toomey S, et al. Characterization of the proteins released from activated platelets leads to localization of novel platelet proteins in human atherosclerotic lesions. Blood. 2004;103:2096–2104. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Coppinger JA, O’Connor R, Wynne K, et al. Moderation of the platelet releasate response by aspirin. Blood. 2007;109:4786–4792. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cramer EM, Breton-Gorius J, Beesley JE, Martin JF. Ultrastructural demonstration of tubular inclusions coinciding with von Willebrand factor in pig megakaryocytes. Blood. 1988;71:1533–1538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gralnick HR, Williams SB, McKeown LP, Krizek DM, Shafer BC, Rick ME. Platelet von Willebrand factor: comparison with plasma von Willebrand factor. Thromb Res. 1985;38:623–633. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(85)90205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bowie EJ, Solberg LA, Jr, Fass DN, et al. Transplantation of normal bone marrow into a pig with severe von Willebrand’s disease. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:26–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI112560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.De Meyer SF, Vandeputte N, Pareyn I, et al. Restoration of Plasma von Willebrand Factor Deficiency Is Sufficient to Correct Thrombus Formation After Gene Therapy for Severe von Willebrand Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.168369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rendu F, Brohard-Bohn B. The platelet release reaction: granules’ constituents, secretion and functions. Platelets. 2001;12:261–273. doi: 10.1080/09537100120068170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hayward CP, Furmaniak-Kazmierczak E, Cieutat AM, et al. Factor V is complexed with multimerin in resting platelet lysates and colocalizes with multimerin in platelet alpha-granules. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19217–19224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jeimy SB, Fuller N, Tasneem S, et al. Multimerin 1 binds factor V and activated factor V with high affinity and inhibits thrombin generation. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:1058–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kiesselbach TH, Wagner RH. Demonstration of factor XIII in human megakaryocytes by a fluorescent antibody technique. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1972;202:318–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1972.tb16344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Monkovic DD, Tracy PB. Functional characterization of human platelet-released factor V and its activation by factor Xa and thrombin. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:17132–17140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gould WR, Silveira JR, Tracy PB. Unique in vivo modifications of coagulation factor V produce a physically and functionally distinct platelet-derived cofactor: characterization of purified platelet-derived factor V/Va. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2383–2393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hu CJ, Baglia FA, Mills DC, Konkle BA, Walsh PN. Tissue-specific expression of functional platelet factor XI is independent of plasma factor XI expression. Blood. 1998;91:3800–3807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Veljkovic DK, Rivard GE, Diamandis M, Blavignac J, Cramer-Borde EM, Hayward CP. Increased expression of urokinase plasminogen activator in Quebec platelet disorder is linked to megakaryocyte differentiation. Blood. 2009;113:1535–1542. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hayward CP, Cramer EM, Kane WH, et al. Studies of a second family with the Quebec platelet disorder: evidence that the degradation of the alpha-granule membrane and its soluble contents are not secondary to a defect in targeting proteins to alpha-granules. Blood. 1997;89:1243–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Novotny WF, Girard TJ, Miletich JP, Broze GJ., Jr Platelets secrete a coagulation inhibitor functionally and antigenically similar to the lipoprotein associated coagulation inhibitor. Blood. 1988;72:2020–2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]