Diffeomorphometry and geodesic positioning systems for human anatomy (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2015 Mar 1.

Published in final edited form as: Technology (Singap World Sci). 2014 Mar;2(1):36. doi: 10.1142/S2339547814500010

Abstract

The Computational Anatomy project has largely been a study of large deformations within a Riemannian framework as an efficient point of view for generating metrics between anatomical configurations. This approach turns D’Arcy Thompson’s comparative morphology of human biological shape and form into a metrizable space. Since the metric is constructed based on the geodesic length of the flows of diffeomorphisms connecting the forms, we call it diffeomorphometry. Just as importantly, since the flows describe algebraic group action on anatomical submanifolds and associated functional measurements, they become the basis for positioning information, which we term geodesic positioning. As well the geodesic connections provide Riemannian coordinates for locating forms in the anatomical orbit, which we call geodesic coordinates. These three components taken together — the metric, geodesic positioning of information, and geodesic coordinates — we term the geodesic positioning system. We illustrate via several examples in human and biological coordinate systems and machine learning of the statistical representation of shape and form.

The low-dimensional matrix Lie groups form the core dogma for the now classic study of the kinematics of rigid bodies in the field of rigid body mechanics. Their infinite dimensional analogue, the diffeomorphism group, containing one-to-one smooth transformations1–6, plays the central role in studying deformable structures in the field of Computational Anatomy (CA)7–15. Central to CA is the comparison of shape and form, morphology, as pioneered by D’Arcy Thompson16. We are focusing on shapes formed by the submanifolds of the human body in _R_3. Comparison of their coordinates are described via flows of diffeomorphisms connecting them. Thompson’s morphological space is made into a metrizable space via a metric induced by the geodesic lengths of the flows. This reduction of the space of human shape and form to a metric space via diffeomorphic connection we call diffeomorphometry.

We formulate the diffeomorphic correspondence as positioning via the design of optimal control strategies flowing information from one anatomical coordinate system onto another. The flows of the coordinates t ↦ φt act to transfer the image information, with the controls the vector fields t ↦ vt acting as the push. They are related via the dynamics of the system φ̇ = v ∘ φ. To define the geodesic shortest path flows a least-action principle is introduced based on a Lagrangian on the generalized coordinates of this system. This links us to classical formulations from physics. The Lagrangian has the property that the metric between any two forms is unchanged by coordinate transformation identically applied to both. Importantly, this property termed right-invariance of the metric, implies that a linear functional of the vector field encoding the geodesic connection between forms satisfies a conservation law.

This linear functional we term the Eulerian momentum. Importantly, conservation implies that the metric comparison of diffeomorphometry is encoded via one of the forms and the Eulerian momentum specifying the geodesic connection of it to the second form. Our parametric reduction to coordinates of the shape or anatomical phenotype is the parametric representation of these linear momenta.

The flows of diffeomorphisms both encode shape as well as transfer the physiological information stored in the imagery. This approach models the observable space of imagery and forms as an orbit under the diffeomorphism group action. We call this orbit the morphological space of forms. It is an example of a Grenander deformable template17, reducing the study of the image or form to the study of the templates and the transformations that are applied. The transfer of information as group action implies the metric property between coordinate systems is inherited by the elements in the orbit itself. This is vital for the quantitative representation of function across multiscale models which link cells and organ systems that characterize variation in health and disease in Computational Medicine18.

This diffeomorphic action is a positioning system providing our space of forms with coordinates, termed Riemannian exponential or geodesic coordinates. To make an analogy in these infinite dimensional coordinatized spaces with coordinates on Earth, choosing a template in CA is equivalent to selecting an origin on the globe, say the North pole. Geodesics stemming from the template are analogous to longitude lines, or great circles stemming from the pole, and CA coordinates select both the geodesic and how far to go along it, similar to providing longitude and latitude in spherical coordinate systems.

Noteably, the diffeomorphic actions are rich enough that the morphological space is homogeneous, so that any form can generate the full orbit and can be the center of a chart creating a local coordinate system with geodesic coordinates. The collection of geodesic maps covers the morphological space and defines the geodesic atlas. Geodesic positioning provides a systematic way to choose the chart which flattens to first order the metric, providing exact distances to the origin radially.

Because the image information indexed to submanifolds M ⊂ _R_3 are so essential for understanding medicine at the human organ system level of subcortical and surface coordinates in brain and heart, our optimal control strategies are reformulated via Hamiltonian reduction of the Lagrangian on _R_3 to the local coordinates M ⊂ _R_3 of physiological significance within the body.

METHODS

The morphological space: transformation of forms via diffeomorphisms

CA examines the interplay between imaged anatomical structures indexed with coordinates, hereafter called a form lying in some set  called the morphological space, and acted upon by some group of transformations, φ ∈ G. Our algebraic model of the interaction between the pair (φ, m) is that the form m ∈

called the morphological space, and acted upon by some group of transformations, φ ∈ G. Our algebraic model of the interaction between the pair (φ, m) is that the form m ∈  is carried by the coordinate system represented by φ ∈ G, and denoted algebraically as group action

is carried by the coordinate system represented by φ ∈ G, and denoted algebraically as group action

The forms studied in CA are submanifolds (points, curves, surfaces, subvolumes) in the human body, and dense scalar and tensor imagery. The transformations are diffeomorphisms φ ∈ G a group of one-to-one, smooth, coordinate change of the background space _R_3, with law of composition φ ∘ _φ_′(·) = (φ(_φ_′(·))), inverse _φ_−1. In functional anatomy19, diffeomorphisms represent the structural phenotypes, with imagery functional phenotypes. This separation is not always distinct.

The diffeomorphic transformations are generated as flows. If vt is a time-dependent vector field on _R_3, the differential equation flow ẏ = vt(y) is given with its inverse, for t ∈ [0, 1], by

| dφtdt=vt∘φt,d(φt-1)dt=-d(φt-1)vt, | (2) |

|---|

where df=(∂fi∂xj) denotes the 3 × 3 Jacobian matrix of _f:R_3 → _R_3, and both equations are solved with initial condition φ0=φ0-1=id, where id(x) = x is the identity mapping. Here φ̇ ∈ _R_3 is the Lagrangian velocity indexed to the initial body configuration, with vt ∈ _R_3 the Eulerian vector field indexed to the flow φt as a function of time t. The flow of (2) generates a well defined time-dependent path of _C_1 diffeomorphisms t → φt with inverse (the transport equation) for suitable control of the spatial derivatives of vt (see below).

Our two kinds of forms are manifolds and imagery, carried by the coordinate transformations of (1). For collections of submanifolds (landmarks, curves, or surfaces) a form M is a subset, usually the geometrical support of a submanifold. Often the manifold of points are parameterized via vertex representations as surfaces in brain and cardiac studies20–23, implying q(U) = M for some mapping q:U → _R_3, where U is taken to be a subset of Euclidean space, although U can be discrete sets or submanifolds. For MRI the forms are images _I:R_3 → Rm, dense scalar or vector functions, action as right inverse. This gives our two actions:

| (φ,M)↦φ·M≐φ(M),(φ,q)↦φ·q=φ∘q. | (3a) |

|---|

| (φ,I)↦φ·I≐I∘φ-1,φ·I(x)=I(φ-1(x)). | (3b) |

|---|

There can be many actions as shown in the extended methods for vector imagery and tensor imagery as 3 × 3 non-negative symmetric matrices, as well as frames or orthonormal bases. Defining in this way specifies the transformation is group action, φ, _φ_′ ∈ G, (φ ∘ _φ_′) · m = φ · (_φ_′ · m) ∈  .

.

Diffeomorphometry via geodesic connection

For turning the “ology” of D’Arcy Thompson’s morphology into the “ometry” of diffeomorphometry we construct a metric  on the morphological space

on the morphological space  of forms, induced by the metric between diffeomorphic changes in coordinates. For this, let φ:[0,1] → G be a differentiable path connecting coordinate systems _φ_0 = g, _φ_1 = h ∈ G. The metric between coordinate transformations is defined as the length of the geodesic connection given by the integrated tangent norm along the flow, which induces the metric between forms m,n ∈

of forms, induced by the metric between diffeomorphic changes in coordinates. For this, let φ:[0,1] → G be a differentiable path connecting coordinate systems _φ_0 = g, _φ_1 = h ∈ G. The metric between coordinate transformations is defined as the length of the geodesic connection given by the integrated tangent norm along the flow, which induces the metric between forms m,n ∈  defined via the exemplar or template _m_0:

defined via the exemplar or template _m_0:

| ρ(g,h)=infφ:φ0=g,φ1=h∫01‖φ.t‖φtdt, | (4a) |

|---|

| ρM(m,n)=infg,h:g·m0=m,h·m0=nρ(g,h). | (4b) |

|---|

The norm-square for the tangent is taken as ‖φ.t‖φt2=‖φ.t∘φt-1‖V2=‖vt‖V2, where ||·||V is the norm for the Hilbert space of vector fields V. To ensure flows satisfying Equation (2) have well defined inverse (requiring Jacobian) and Equation (4) has well defined length for every pair of diffeomorphisms, we constrain the vector fields to be in the Hilbert space ν ∈ V modeled as continuously embedded in continuous, differentiable in space, vector fields with supremum norm so that Eulerian velocities v ∈ V are spatially _C_1.

Statement 1

G≐{φ=ϕ1:∫01‖vt‖Vdt<∞,ϕ.t=vt∘ϕt,ϕ0=id},

with orbit of forms  = {m:m = φ · _m_0, φ ∈ G}.

= {m:m = φ · _m_0, φ ∈ G}.

- Then

is homogeneous under action G, so that for all m, _m_′ ∈

is homogeneous under action G, so that for all m, _m_′ ∈  , there exists φ ∈ G, such that _m_′ = φ · m.

, there exists φ ∈ G, such that _m_′ = φ · m. - With ‖φ.t‖φ=‖φ.t∘φt-1‖V=‖vt‖V in Equation (4), the metric is right-invariant, for all ψ ∈ G,

The group action property implies getting from one form to another is possible, extending to morphological spaces the property familiar from the kinematics of rigid bodies in Euclidean space, called homogeneity of the action; see Fig. 1.

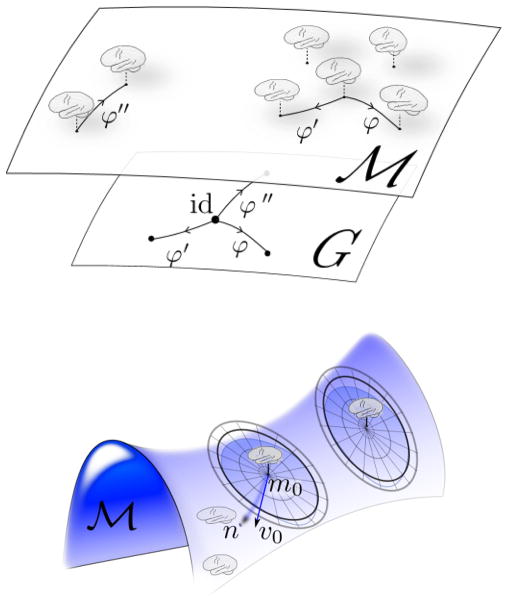

Figure 1.

Top panel shows the orbit of forms M, and acting group G. Bottom panel shows radial representation of geodesic flattening of forms. Tangent space norm and geodesic distance agree for radial great circles emanating from the template _m_0 with distance  (_m_0,n) = ||_v_0||V.

(_m_0,n) = ||_v_0||V.

The metric being right-invariant implies that (i) the metric on the orbit of forms satisfies the triangle inequality in spite of there being many diffeomorphisms which are indistinguishable seen through their action24, and (ii) computation of geodesics reduces to shooting from the identity.

It also gives us a consistency property when manipulating the forms. We would prefer our metric to have the property that it obtains consistent measurements across different scales, parameterizations, or extent of inclusion of subparts. For this we define the notion of the extension of one form from another. We say  is an extension of

is an extension of  if there exists an onto mapping π:

if there exists an onto mapping π: → M that is consistent with the group action: π(φ · _m_′) = φ · π(_m_′), φ ∈ G.

→ M that is consistent with the group action: π(φ · _m_′) = φ · π(_m_′), φ ∈ G.

The right invariance of the metric is necessary and sufficient for metric consistency to hold.

Statement 2

- The metric

on forms m,n ∈

on forms m,n ∈  shoots from identity, satisfying triangle inequality24:

shoots from identity, satisfying triangle inequality24: ρM(m,n)=infg:g·m=nρ(id,g). (6a) - The metric

on forms is consistent, for any extension π(φ · _m_′) = φ · π(_m_′), then

on forms is consistent, for any extension π(φ · _m_′) = φ · π(_m_′), then ρM(m,n)=infm′:π(m′)=m,n′:π(n′)=nρM′(m′,n′). (6b)

Importantly this provides a straightforward mechanism for a purely geometric comparison or shape registration of manifolds, independent of parametrization by implicit or explicit optimization over all possible reparametrizations, finding the most favorable one for the distance25.

Geodesic coordinates and positioning

We compute geodesics as variational minimizers along the integrated Lagrangian or kinetic energy L(φ,φ.)=12‖v‖V2; computation of geodesics corresponds to a least-action principle:

| ρ(g,h)2=infv:φ.t=vt∘φtφ0=g,φ1=h(2∫01L(φt,φ.t)dt=∫01‖vt‖V2dt). | (7) |

|---|

For computing geodesics we use a matrix differential operator L (powers of the Laplacian) to rewrite the norm in V giving ‖v‖V2=(Lv∣v) and inner-product for v,w ∈ V, taken componentwise (Lv∣w)≐∑i=13∫R3Lvi(x)wi(x)dx. We call μ = Lv the Eulerian momentum; sometimes it is a measure.

The Euler equation dictates the temporal evolution of the momentum of the geodesics. The right-invariant metric implies conservation of Eulerian momentum so that the geodesics are encoded by their initial condition, the basis for shooting. In Eulerian coordinates, in passing from t ↦ t + ε, the particles are at different positions, so for conservation the function being acted upon must be transformed by the adjoint w↦((dφt)w)∘φt-1.

Statement 3

The geodesics minimizing the action of (7) with ‖v‖V2=(Lv∣v) have Euler momentum satisfying force evolution and conservation on smooth functions w ∈ V:

| (dLvtdt|w)+(Lvt∣(dvt)w-(dw)vt)=0, | (8a) |

|---|

| (Lvt∣((dφt)w)∘φt-1)=(Lv0∣w). | (8b) |

|---|

Moreover, geodesics have constant speed ||_v_0||V and Lagrangian L(φ,φ.)=12‖v0‖V2 (proven in10).

The operations consisting in finding an optimizing geodesic in Equations (7) and solving (8) with initial condition _Lv_0 are inverse. Under suitable conditions, solutions of the latter are minimizers of the former and conversely. This “inverse” relationship is referred to as the Riemannian exponential and logarithm, with the logarithm only well defined when there are unique solutions to the geodesic equation.

Statement 4

We term geodesic positioning as the Riemannian exponential at the identity Expid(·):V → G given by the geodesic satisfying Equation (8) with initial condition _vt_=0 = _v_0; geodesic coordinates are the Riemannian logarithm at the identity Logid(·) G → V (assuming uniqueness) given by _vt_=0 of the field satisfying geodesic connection:

| Expid(v0)=g,withLogid(g)=v0. | (9) |

|---|

Extending to the entire group gives

| Expg(v0∘g)≐Expid(v0)∘gwithLogg(h)≐Logid(h∘g-1)∘g. | (10) |

|---|

When the logarithm exists we have Expid(Logid(g)) = g, but the converse equation Logid(Expid(_v_0)) = _v_0 may fail to be true, although it holds if _v_0 is “small enough”.

As depicted in Fig. 1, the top panel shows diffeomorphic actions which are rich enough that any form can generate the full orbit (homogeneity of the space). The bottom panel shows each form can act as the center of a chart creating a local coordinate system with geodesic coordinates. In this infinite dimensional setting, any one could be selected, analogous to selection of the North pole in finite dimensional spherical representations. The collection of geodesic maps covers the morphological space and defines the geodesic atlas. The metric flattens to the tangent providing exact distances to the origin radially of the great circles stemming from the template given by  (m,n) = ||_v_0||V. The fact that our forms are defined by group actions implies this is true for all of the actions defined, including imagery and manifolds.

(m,n) = ||_v_0||V. The fact that our forms are defined by group actions implies this is true for all of the actions defined, including imagery and manifolds.

Computation of Geodesic Positioning System (GPS) via optimal control and Hamiltonian reduction

We solve for geodesic position and coordinates for Log and Exp as an inexact matching of coordinate systems using classical methods in optimal control. In CA, vector fields are used as control that push the forms (submanifolds or images) within the anatomical morphological space. We take as the dynamical system the flow of coordinates t ↦ qt ≐ φt · _q_0 ∈ Q modelled as embedded in some linear state space Q ⊃ M, and the control the vector field t ↦ vt ∈ V related to the state via the infinitesimal action of the flow q̇t = vt · qt,_qt_=0 = _q_0. The optimal control takes the running cost the kinetic energy (Lvt∣vt)=‖vt‖V2, with an assumed target or endpoint condition E.

Control Problem 1

| minv:φ.t=vt∘φt,φ0=idC(v)≐12∫‖vt‖V2dt+E(φ1·q0) | (11a) |

|---|

| minv0C(v0)≐12∫‖v0‖V2+E(Expid(v0)·q0). | (11b) |

|---|

The control indexed to initial _v_0 is shooting and has been examined in various forms4,10,25–32. Various endpoint conditions have been examined, including for dense image and tensor matching E=12‖φ·I-J‖22, for point matching with correspondence E=12∑i∣yi-φ(xi)∣2, as well as other for point-sets, curves and surfaces without correspondence.

Forms in the orbit being positioned can be of reduced dimension to the diffeomorphisms in the group. Manifolds represented by multiple organs or fiducial points are singular in the background space indexing the vector fields. The GPS computation exploits this by switching to a Hamiltonian formalism in which the momentum is reparameterized in terms of a co-state variable p indexed to the lower complexity state space of the forms. Introduce a Lagrange multiplier pt dual to the state space for constraining q̇t = vt · qt added to the negative Lagrangian, giving control-dependent Hamiltonian

| Hv(q,p)=(p∣v·q)-12(Lv∣v). | (12) |

|---|

The Pontryagin Maximum principle yields the optimized geodesic control v̂, and the Hamiltonian H(q, p) = max_vHv_(q, p) with dynamics

| (q.p.)=(∂H(q,p)/∂p-∂H(q,p)/∂q)≐F(q,p),q0=fixed. | (13) |

|---|

Our shooting problem for qt = φt · _q_0, q̇t = vt · qt has been reduced to the geodesic control v̂ with momentum Lv̂ satisfying Euler Equation (8) with Hamiltonian constant equalling the Lagrangian:

H(q,p)=H(q0,p0)=12‖v^0‖V2.

The reduced control problem becomes as follows.

Control Problem 2

Hamiltonian Reduction

| minp0C(p0)=H(q0,p0)+E(q1)subjectto(q.p.)=F(q,p),q0=fixed. | (14) |

|---|

For manifolds M = q(U), q : U → _R_3, qt = φt ∘ _q_0, the infinitesimal action is v · q ≐ v ∘ q with Lagrange multiplier co-state constraint

| v·q≐v∘q,(p∣v∘q)≐∫U〈p(u),v∘q(u)〉du. | (15) |

|---|

Maximizing Hv(p,q) of (12) in v with K = _L_−1 gives Dirac geodesic momentum and optimizing vector field satisfying Equation (8):

| Lv^=∫Uδq(u)⊗p(u)du,v^(·)=∫UK(·,q(u))p(u)du. | (16) |

|---|

The manifold dynamical system becomes

| (q.p.)=(v^∘q-(dv^)∗∘qp)=F(q,p), | (17a) |

|---|

| H(q,p)=12∫U2p∗(u)K(q(u),q(u′))p(u′)du′du=H(q0,p0)≐12(p0∣Kq0q0p0)=12‖v^0‖V2, | (17b) |

|---|

where we use (·)* to denote matrix transpose.

For dense imagery, qt=I∘φt-1_,q_0 = I, the infinitesimal action is v · q = −〈∇q, _v_〉 with Lagrange multiplier co-state constraint

| (p∣-〈∇q,v〉)=-∫R3p(x)〈∇q(x),v(x)〉dx. | (18) |

|---|

Maximizing Hv(p, q) of (12) in v gives geodesic momentum and vector field satisfying Equation (8):

| Lv^=-p∇q,v^(·)=-∫R3K(·,x)∇q(x)p(x)dx. | (19) |

|---|

The dense image dynamical system becomes

| (q.p.)=(-〈∇q,v^〉∇·(pv^))=F(q,p); | (20a) |

|---|

| H(q,p)=12∫R3×R3(p∇q)∗(x)K(x,y)(p∇q)(y)dxdy=H(q0,p0)≐12(p0∣Kq0q0p0)=12‖v^0‖V2. | (20b) |

|---|

The Extended Methods does the case of atlases as collection of multiple manifolds.

Adjoint method of solution

For solving control problem 2 we use gradient based adjoint methods27,33–35 transporting the endpoint condition backwards, reoptimizing with respect to _p_0 with Hamiltonian dynamics F(q, p).

The adjoint method arises by introducing the functional determining our gradient method

| ∫01(λ|(q.p.)-F(q,p))dt+H(q0,p0)+E(q1), | (21) |

|---|

where λ_t_ is the Lagrange multipler with

(λt|(fg))=∫U(λt,q(u)f(u)+λt,p(u)g(u))du.

The gradient variation under a perturbation (q, p) → (q, p) + δ(q, p) gives equations for λ:

| (λ.+dF∗(q,p)λ∣δ(q,p))=0 | (22a) |

|---|

| (dH(q0,p0)-λ0∣δ(q0,p0))=0 | (22b) |

|---|

| λ1,p=0,(∂E(q1)∂q+λ1,q∣δq1)=0, | (22c) |

|---|

where dH is the differential with respect to (q, p).

See the Extended Methods gradient algorithm Equations (32) for solving the maximizer conditions.

RESULTS

Geodesic positioning in high field MRI

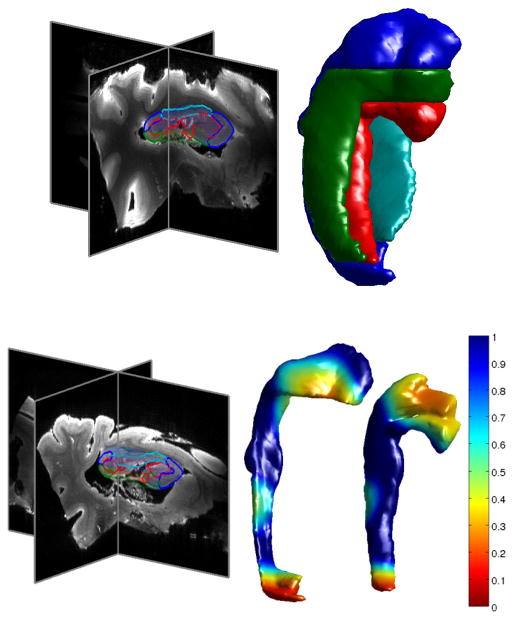

Figure 2 illustrates geodesic positioning for segmentation via deformable templates36,37. The top row shows a high field 11.7T MRI reconstructed hippocampus38 from a normal control which has been partitioned into four substructures, with dense subvolumes and bounding surfaces: _M_0 equal to CA1 (blue), CA2 (green), CA3/Dentate gyrus (red), and subiculum (cyan). Taking this as the template _M_0 is used to parcellate or segment the target in the lower panel by positioning it onto the target coordinates φ · _M_0 = Expid(_v̂_0) · _M_0 with _v̂_0 = Logid (φ). The target has been selected manifesting temporal lobe atrophy. The left part of the bottom panel shows the cross sections of the mapped template in the MRI. The right of the bottom panel shows the mapped template with two of the substructures CA1 and CA3/Dentate shown in the atrophied coordinates of the target. These two substructures illustrate the greatest atrophy, with CA3/Dentate gyrus showing the greatest amount of atrophy as much as 25 percent in target coordinates as measured by the determinant of the Jacobian. The geodesic positioning encoded by φ = Expid(_v̂_0) was determined by associating landmarks to each of the _M_0, _M_1 structures and solving the optimal Control Prob. 3 via landmark matching10.

Figure 2.

Showing mapping in high field 11.7T hippocampus depicting the partition into CA1 (blue), CA2 (green), CA3/Dentate (red) and Subiculum (cyan) of target structures exhibiting temporal lobe atrophy. Top shows four structures in section from the template corresponding to an age controlled normal showing reconstructions of CA1, CA2, CA3/ Dentate, subiculum. Bottom shows template mapped to the target an individual suffering from temporal lobe atrophy; right structures are CA1, CA3/Dentate colored with Jacobian determinant. Data collected is three-dimensional diffusion tensor imaging and was performed using a horizontal-bore 11.7 T NMR scanner (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA). DTI data were acquired with a 3D diffusion-weighted EPI sequence (TE = 27 ms, TR = 500 ms). The imaging field-of-view was 42 mm × 45 mm × 64 mm. Two b0 images and 30 diffusion directions were acquired within a scan time of 13.5 hours for DTI mapping.

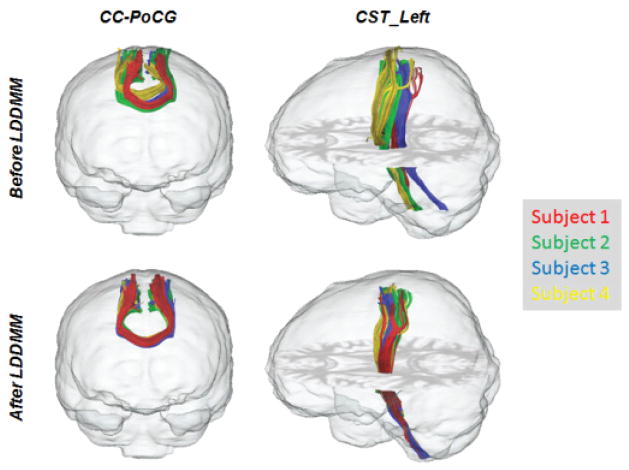

Geodesic positioning of brain DTI tracts

Shown in Fig. 3 is geodesic positioning used by many groups in Computational Anatomy registering information in diffusion tensor MRI (DT-MRI). Top row of Fig. 3 shows submanifold curves generated via FACT tract tracing39 from twenty brains following rigid alignment to MNI space. The commissural fiber connecting the postcentral gyri (CC-PoCG, Fig. 3 left column) and the left cortical-spinal tract (CST-Left, Fig. 3 right column) are shown for demonstration. Following40, the MRI coordinates were repositioned aligning the brains to a common template coordinate system I0↔φ(i)Ii solving control problem 1 based on the fractional anisotropy and B0 contrasts in the DWI imagery using Multi-channel LDDMM41. The bottom row shows the fiber tracts regenerated after aligning the brains to the common template coordinate system.

Figure 3.

Geodesic positioning of the DT-MRI and alignment of fiber tracts. Three-dimensional diffusion tensor imaging of 20 subjects were performed on a 1.5T Siemens MR unit using single-shot echo-planar imaging sequences with sensitivity encoding (SENSE EPI) with parallel imaging factor of 2.0 (imaging matrix: 96 × 96, field-of-view: 240 mm × 240 mm, and slice thickness 2.5 mm). B0 images and DWIs of 30 diffusion directions were acquired and co-registered to remove eddy current and motion. The scanning time was 4 min per dataset. Tensor calculation was performed, followed by rigid alignment of all subjects. Fiber reconstructions were performed in each subject’s space using FACT tract tracing algorithm 39. CC-PoCG fiber: the starting and ending points of tract tracing were selected as the post-central gyri (PoCG) of the two hemispheres, and the fiber path was constraint to penetrate the corpus callosum (CC). CST_left fiber: the starting and ending points were the cerebral peduncle (CP) and the pre-central gyrus (PrCG); the fiber path was constrained by the posterior limb of internal capsule (PLIC) and the superior corona radiata (SCR). Top row shows the tracts in native brain (4 subjects were shown for demonstration); bottom row shows tracts after geodesic positioning via LDDMM solution of control problem 1.

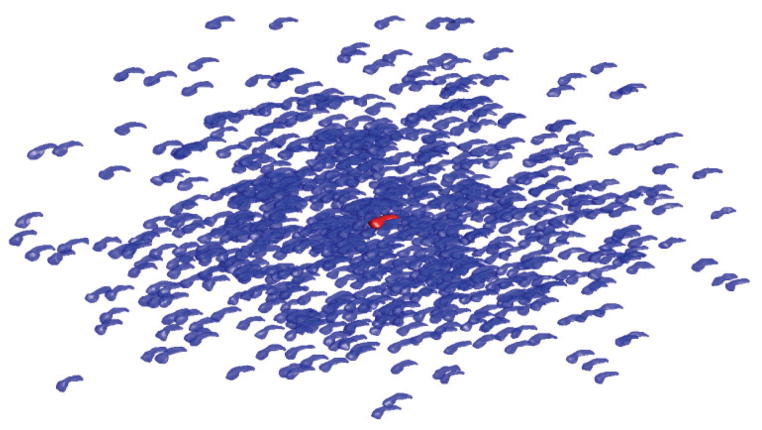

Exponential geodesic coordinates in brain and machine learning

Figure 4 depicts the use of geodesic coordinates to visualize populations of structures around the templates. Shown is the geodesic positioning of the single hippocampus subcortical structure from a population in the BIOCARD study. For the graph the population was mapped solving control problem 2 to a common template form using template estimation as in35,42. For each structure Mi the diffeomorphism was calculated M0↔φ(i)Mi, solving Control Prob. 2 for surface matching 27, from which exponential coordinates were calculated Logid(φ(i)) = v(i). Figure 4 shows the two-dimensional PCA representation of the exponential vector field coordinates of the mapped structures. Shown at the center is the template.

Figure 4.

Panel shows structures indexed by two highest variance dimensions from PCA on Riemannian exponential coordinates representing hippocampus structures from the BIOCARD study. Each structure is placed on the 2D plane with the template (red) at (0,0) in the center, left/right corresponding to the first dimension, and up/down corresponding to the second.

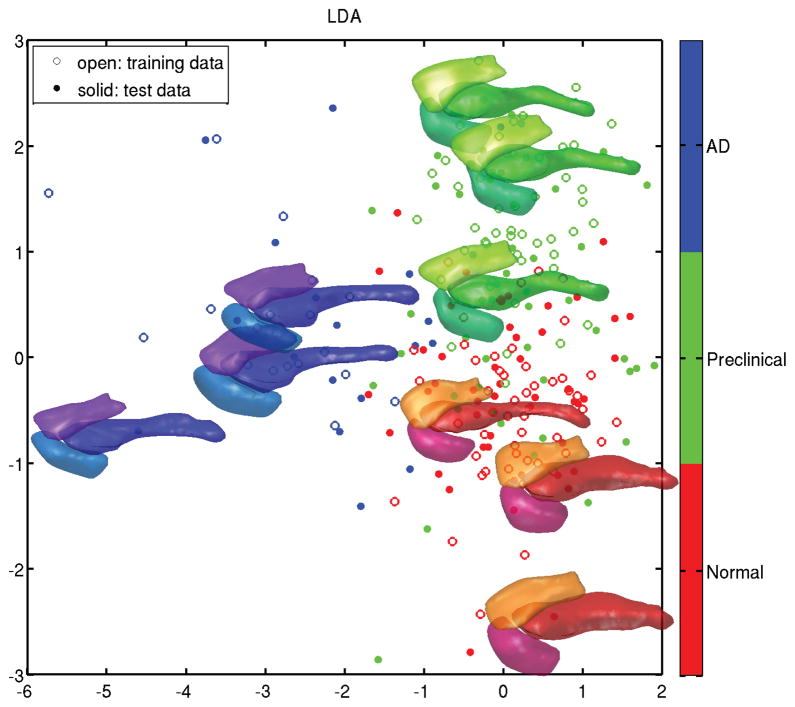

Figure 5 is an illustration of using these exponential coordinates for machine learning of temporal lobe structures, amygdala-entorhinal cortex-hippocampus in the BIOCARD study. Shown in the Figure are results of machine learning using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) on the exponential coordinates, with 50% of the data witheld for training. The population was mapped solving control problem 2 to a common template as above and for each structure Mi the diffeomorphism was calculated, from which exponential coordinates were calculated. A finite dimensional basis was generated from the coordinates for each mapping {v(i)}, expanding in a PCA basis based on the empirical covariance. Up to 50 anatomies are shown placed in the first two LDA coordinates for each group showing red for normal, green for clinical Alzheimer’s disease, and blue for those diagnosed subsequent to their last scan and termed pre-clinical. Three of the 50 examples from each group are plotted showing the surface temporal lobe structures.

Figure 5.

Panel shows results of machine learning (LDA) on the geodesic coordinates for sets of temporal lobe structures, amygdala-entorhinal cortex-hippocampus, with 50% witheld for training. Up to 50 points are placed for each group, with three examples from each group shown as surfaces. Red: normal elderly subjects, green: subjects diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at time of their last scan, blue: subjects diagnosed subsequent to their last scan and termed pre-clinical.

Geodesic coordinates for heart shape

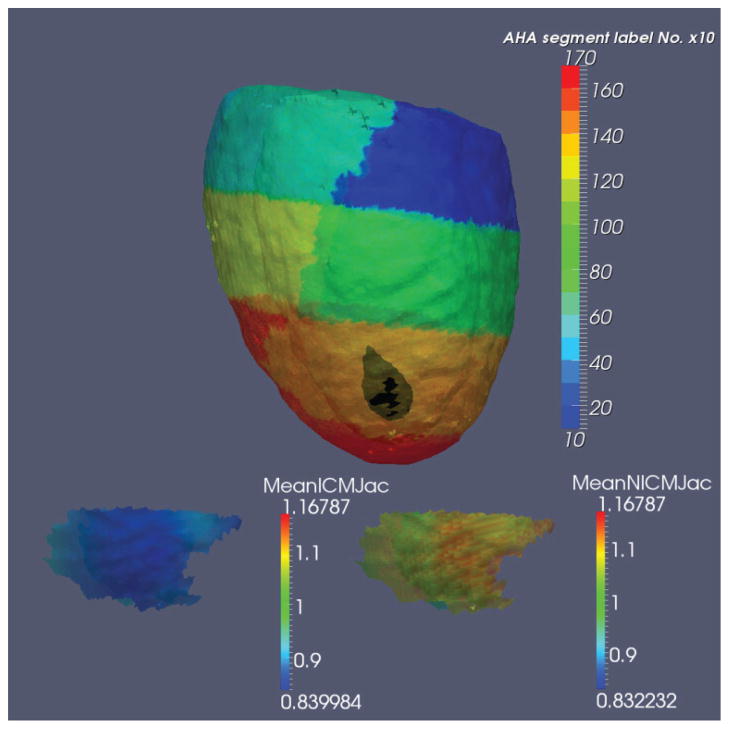

The geodesic exponential coordinates are the basis for many machine learning and statistical methods for discrimination and indexing of shapes. Figure 6 shows results in hearts. The top shows a reconstruction of a high resolution computed tomography left ventricular template (1 mm isotropic) generated from a population of 25 subjects. Shown in color is the 17 AHA partition43 with each segment represented by one color and using the ontology definitions44. The population of 25 heart geometries were positioned solving control problem 2 using LD-DMM45 for the dense imagery. Figure 6 depicts the use of Riemannian coordinates for statistical encoding of the shape phenotype. For this the population was mapped solving control problem 1 generating coordinates v̂(i) = Logid(φ(i)) defined by template to target maps I0↔φ(i)Ii representing the shape phenotype positioned relative the template heart coordinate system. Shown depicted via the black area is the indicated region that was statistically significant between the two different populations of ischemic versus non-ischemic cardiomyopathy at end-systole46. The region is AHA segment 13 (anterior apical) where the majority of ischemic patients had their infarction. Bottom panel illustrates the spatial distribution of average determinant of Jacobian for the ischemic (left) and non-ischemic (right) populations within AHA segment 13. Ischemic patients have smaller Jacobian determinant indicating wall thinning due to scar formation.

Figure 6.

Top section: A high resolution computed tomography left ventricular template (1 mm isotropic) constructed from 25 subjects in AHA segmentation represented by one color per segment; black area within AHA anterior apical segment 13, showing statistical significance between two different populations of cardiac disease, ischemic (n = 13, 10 men, mean age 56) and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy (n = 12, 8 men, mean age 52) at end-systole. Each subject was studied either in a 32 (n = 8) or 64-detector (n = 17) multi-detector computed tomography scanner (Aquilion 32(64), Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Otawara, Japan). Plane resolution varied from 0.36 × 0.36 mm to 0.45 × 0.45 mm, thickness = 0.5 mm. Bottom section shows average Jacobian for ischemic (left) and non-ischemic (right) groups within segment 13 highlighting that on average non-ischemic group had significantly larger tissue (myocardial) volume relative to ischemic group at end-systole. This indicates smaller wall thickening during maximum contraction at the location of infarction in ischemic population46.

DISCUSSION

The fact that the right-invariant diffeomorphometry metric is consistent provides a straightforward mechanism for a purely geometric comparison of manifolds, independent of the parametrization. This can be contrasted with other methods in CA that equip shapes with a predefined parametrization such as Euclidean or spherical coordinates47–49. In the extended methods we illustrate via various reparameterization examples.

It is informative to compare control problem 2 for dense matching of I to J to LDDMM50 using Equation (19) relating Lv̂ = −p_∇_q with the state q = I ∘ _φ_−1. Dense image matching minimizes endpoint

with ||·||2 the squared-error norm over the image. In this case the Hamiltonian provides geodesic coordinates giving the reduction from _Lv̂_0 : _R_3→ _R_3 to _p_0: _R_3 → R, reducing the dimension of φ,φ̇ = v ∘ φ which are 3-vectors to the reduced dimension co-state scalar field. To calculate _p_0, we use conservation to transport the endpoint condition on _p_1 back to the origin giving _p_0. The endpoint for _p_1 maximizes control problem 2:

| p1=-∂E∂q(q1)=-(q1-J)=-(I∘φ1-1-J). | (24) |

|---|

For E(q_1) smooth, then Lv has vector density (Lvt |w) = ∫_R_3 〈 mt (x), w(x)〉_dx with conservation Equation (8b) obtaining the initial density,

| m0=∣dφ1∣(dφ1)∗m1∘φ1. | (25) |

|---|

Using _q_0 = _q_1 ∘ _φ_1, ∇_q_0 = (_dφ_1)* ∇_q_1 and Equations (19) and (24), gives maximizer conditions of LDDMM50:

| Lv^1=m1=-p1∇q1=-(I∘φ1-1-J)∇(I∘φ1-1).Lv^0=m0=∣dφ1∣(dφ1)∗m1∘φ1=∣dφ1∣(J∘φ1-I)∇I. | (26) |

|---|

The geodesic trajectory in the group is characterized by the initial Eulerian momentum from Equation (19) given by _Lv̂_0 = −_p_0∇_q_0, q_0 = ∇_I fixed for the template, with _p_0: _R_3→ R the reduced co-state,

For pointset correspondence matching {xi} to {yi}, then U = {xi} and state qi = φ(xi) with smooth endpoint and vector endpoint condition

| E=12∑t∣yi-φ(xi)∣2,p1=-∂E∂q(q1)=(q1-y). | (28) |

|---|

Then Equation (16) for Eulerian momentum is singular,

| Lv^t=∑iδqti⊗pti,v^t(·)=∑iK(·,qti)pti. | (29) |

|---|

The conservation Equation (8b) for pointsets gives p_0_i = (dq_1_i)* p_1_i, implying the reduction

p0i=(dq1i)∗(q1i-yi),Lv^0=∑iδq0i⊗(dq1i)∗(q1i-yi).

EXTENDED METHODS

Group actions

Here are several other group actions. For images represented by vector fields, _I : R_3 → _R_3, then

φ·I=((dφ)I)∘φ-1orφ·I=((dφ-1)∗I)∘φ-1,

where (_dφ_−1)* holds for (dφ*)−1.

When I = (_I_1, _I_2, _I_3) is a vector field of frames, specifically a positively oriented orthonormal basis of _R_3 denoting the tangent to some curves, and the two other normal vectors forming the Frenet frame, then

φ·I=((dφ)I1‖(dφ)I1‖,(dφ-1)∗I3×(dφ)I1‖(dφ-1)∗I3×(dφ)I1‖,(dφ-1)∗I3‖(dφ-1)∗I3‖)∘φ-1,

where we have denoted vector cross product as Ii × Ij. The interpretation is that _I_1 deforms as a fiber (a tangent to some curve), _I_3 deforms like a normal to the plane generated by _I_1, _I_2 and the deformation of _I_2 is uniquely constrained by the fact that the basis is positive and orthonormal.

For tensor images 3 × 3 non-negative symmetric matrices, Alexander and Gee51 used rotation of the eigenfunctions via the previous action on frames with eigenvalues unchanged; a second action becomes

Consistency of metric

To understand geometric comparison of manifolds, independent of the parametrization examine _q_′ _: U_′ → _R_3 ∈  as a parametrized surface with π(q) ∈

as a parametrized surface with π(q) ∈  the restriction of q to a finite set U ⊂ _U_′ of fiducial points. The statement 2 asserts that the construction that projects

the restriction of q to a finite set U ⊂ _U_′ of fiducial points. The statement 2 asserts that the construction that projects  onto

onto  via the right-hand side of (6) is equivalent to applying the construction in statement 2 directly on

via the right-hand side of (6) is equivalent to applying the construction in statement 2 directly on  . Another important consequence is that changing the parametrization from U → _R_3 to Ũ → _R_3 when U and Ũ are diffeomorphic does not affect the metric.

. Another important consequence is that changing the parametrization from U → _R_3 to Ũ → _R_3 when U and Ũ are diffeomorphic does not affect the metric.

This is again a purely geometric comparison of manifolds, independent of the parametrization. Take  to be the set of mappings q : U → _R_3 such that q(U) is a submanifold of _R_3 (i.e., the set of embeddings) and

to be the set of mappings q : U → _R_3 such that q(U) is a submanifold of _R_3 (i.e., the set of embeddings) and  the set of submanifolds of _R_3. Define π(q) = q(U) which associates to each mapping q the subset of _R_3 that it parametrizes. Then, φ ∘ π(q) = φ ∘ q(U) = π (φ ∘ U) and statement 2 implies a distance between submanifolds is obtained

the set of submanifolds of _R_3. Define π(q) = q(U) which associates to each mapping q the subset of _R_3 that it parametrizes. Then, φ ∘ π(q) = φ ∘ q(U) = π (φ ∘ U) and statement 2 implies a distance between submanifolds is obtained

ρM(m,n)=infq,q∼:q(U)=m,q∼(U)=nρM′(q,q∼).

Atlases of multiple submanifolds

This generalizes for atlases collections of manifolds q = (_q_1, …, qn), qi : Ui → _R_3, with infinitesimal action v · q ≐ (v ∘ _q_1,…,v ∘ qn). Define p = (_p_1,…,pn) yielding (p∣v·q)=∑i=1n(pi∣v∘qi), optimal control

| v^(·)=∑i∫UiK(·,qi(u))pi(u)du. | (30) |

|---|

The dynamics and Hamiltonian becomes

| (q.ip.i)=(v^∘qi-(dv^)∗∘qipi)=Fi(q,p) | (31a) |

|---|

| H(q,p)=H(q0,p0)=12∑i,j(p0i∣Kq0iq0jp0j). | (31b) |

|---|

Adjoint gradient algorithm

The adjoint algorithm arises by implementing the gradient perturbation (q, p) → (q, p) + δ(q, p) of Equations (21) and (22) to satisfy the fixed point optimizer.

Algorithm 1

Generic Adjoint Initialize _p_0.

- Given _p_0 solve (q̇, ṗ)* = F(q, p), giving _p_1, _q_1.

- Given _q_1, solve boundary terms λ1,q=-∂E∂q(q1).

- Backsolve adjoint equation for λ of (22a):

- Compute gradient term (22b) with _q_0 fixed and H(q0,p0)=12(p0∣Kq0q0p0), giving update

p0new←p0old+ε(Kq0q0-1λ0,p-p0old) (32b) with ε = step − size and set p0=p0new and go to (i).

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this paper to Ulf Grenander the father of Metric Pattern Theory. We thank Drs. Truncoso, Aggarwal and Mori for the 11.7T hippocampus supported by NIH grant EB003543. The authors were supported by grants R01 MH056584, R24 HL085343, R01 EB000975, P50 MH071616, R01 EB001838, P41 EB015909, P41 EB015909, R01 EB008171, R01 MH084803, RR025053-01, U01 NS082085-01 and the ANR HMTC. Data used in Figures 4,5 were obtained from the Bio-markers of Cognitive Decline Among Normal Individuals (BIOCARD) study supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health U01-AG033655; a list of Cores can be found at http://www.biocard-se.org/public/Core%20Groups.html. The data in Figure 6 was obtained from the Donald W. Reynolds Cardiovascular Clinical Research Center at The Johns Hopkins Hospital supported in part by grants from Reynolds foundation.

References

- 1.Younes L. Shapes and diffeomorphisms. Shapes and Diffeomorphisms. 2010;171:1–434. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen GE, Rabbitt RD, Miller MI. Deformable templates using large deformation kinematics. IEEE Trans Image Process. 1996;5:1435–1447. doi: 10.1109/83.536892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trouve A. Action de groupe de dimension intinie et reconnaissance de formes. C R Acad Sci Paris Ser 1 Math. 1995;321:1031–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dupuis P, Grenander U, Miller MI. Variational problems on flows of diffeomorphisms for image matching. Quart Appl Math. 1998;56:587–600. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avants BB, Schoenemann PT, Gee JC. Lagrangian frame diffeomorphic image registration: Morphometric comparison of human and chimpanzee cortex. Med Image Anal. 2006;10:397–412. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avants B, Gee JC. Geodesic estimation for large deformation anatomical shape averaging and interpolation. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson PM, Toga AW. A framework for computational anatomy. Comput Visual Sci. 2002;5:13–34. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toga AW, Thompson PM. Maps of the brain. Anat Rec. 2001;265:37–53. doi: 10.1002/ar.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller MI, Trouve A, Younes L. On the metrics and Euler-Lagrange equations of computational anatomy. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2002;4:375–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.092101.125733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller MI, Trouve A, Younes L. Geodesic shooting for computational anatomy. J Math Imaging Vis. 2006;24:209–228. doi: 10.1007/s10851-005-3624-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grenander U, Miller MI. Computational anatomy: An emerging discipline. Quart Appl Math. 1998;56:617–694. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grenander U, Miller MI. Pattern Theory: From Representation to Inference. Oxford University Press; Oxford, New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pennec X. Statistical computing on manifolds: From Riemannian geometry to computational anatomy. Emerg Trends Visual Comput. 2009;5416:347–386. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashburner J. Computational anatomy with the SPM software. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;27:1163–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi S, Davis B, Jomier M, Gerig G. Unbiased diffeomorphic atlas construction for computational anatomy. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson DAW. On Growth and Form. Cambridge University Press; England: 1917. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grenander U. General Pattern Theory: A Mathematical Study of Regular Structures. Clarendon University Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winslow RL, Trayanova N, Geman D, Miller MI. Computational medicine: Translating models to clinical care. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(158):158rv11. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller MI, Qiu AQ. The emerging discipline of computational functional anatomy. Neuroimage. 2009;45:S16–S39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haller JW, Banerjee A, Christensen GE, Gado M, Joshi S, Miller MI, Sheline Y, Vannier MW, Csernansky JG. Three-dimensional hippocampal MR morphometry with high-dimensional transformation of a neuroanatomic atlas. Radiology. 1997;202:504–510. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.2.9015081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiu AQ, Fennema-Notestine C, Dale AM, Miller MI. Neuroimaging AsD. Regional shape abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2009;45:656–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younes L, Ratnanather JT, Brown T, Aylward E, Nopoulos P, Johnson H, Magnotta VA, Paulsen JS, Margolis RL, Albin RL, Miller MI, Ross CA PREDICT-HD Investigators and Coordinators of the Huntington Study Group. Regionally selective atrophy of subcortical structures in prodromal HD as revealed by statistical shape analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012 doi: 10.1002/hbm.22214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Durrleman S, Pennec X, Trouve A, Ayache N. Statistical models of sets of curves and surfaces based on currents. Med Image Anal. 2009;13:793–808. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller MI, Younes L. Group actions, homeomorphisms, and matching: A general framework. Int J Comput Vis. 2001;41:61–84. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaillant M, Glaunes J. Surface matching via currents. Proc Inform Process Med Imaging. 2005;3565:381–392. doi: 10.1007/11505730_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trouve A, Vialard FX. Shape splines and stochastic shape evolutions: A second order point of view. Quart Appl Math. 2012;70:219–251. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tward DJ, Ma J, Miller MI, Younes L. Robust diffeomorphic mapping via geodesically controlled active shapes. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2013;2013:205494. doi: 10.1155/2013/205494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaillant M, Miller M, Younes L, Trouve A. Statistics on diffeomorphisms via tangent space representations. Neuroimage. 2004;23:S161–S169. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vialard FX, Risser L, Rueckert D, Cotter CJ. Diffeomorphic 3D image registration via geodesic shooting using an efficient adjoint calculation. Int J Comput Vis. 2012;97:229–241. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotter CJ, Holm DD. Continuous and discrete clebsch variational principles. Found Comput Math. 2009;9:221–242. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage. 2007;38:95–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allassonniere S, Trouve A, Younes L. Geodesic shooting and diffeomorphic matching via textured meshes. Lect Notes Comput Sci. 2005;3757:365–381. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niethammer M, Huang Y, Vialard FX. Geodesic regression for image time-series. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2011;14:655–662. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-23629-7_80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu A, Younes L, Miller MI. Principal component based diffeomorphic surface mapping. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2012;31:302–311. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2011.2168567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma J, Miller MI, Younes L. A Bayesian generative model for surface template estimation. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/974957. pii: 974957. Epub 2010 Sep 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christensen GE, Joshi SC, Miller MI. Volumetric transformation of brain anatomy. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1997;16:864–877. doi: 10.1109/42.650882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang X, Oishi K, Faria AV, Hillis AE, Albert MS, Mori S, Miller MI. Bayesian parameter estimation and segmentation in the multi-atlas random orbit model. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aggarwal M, Zhang JY, Pletnikova O, Crain B, Troncoso J, Mori S. Feasibility of creating a high-resolution 3D diffusion tensor imaging based atlas of the human brainstem: A case study at 11.7 t. Neuroimage. 2013;74:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mori S, Crain BJ, Chacko VP, van Zijl PCM. Three-dimensional tracking of axonal projections in the brain by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:265–269. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199902)45:2<265::aid-ana21>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Zhang J, Oishi K, Faria AV, Jiang H, Li X, Akhter K, Rosa-Neto P, Pike GB, Evans A, Toga AW, Woods R, Mazziotta JC, Miller MI, van Zijl PC, Mori S. Atlas-guided tract reconstruction for automated and comprehensive examination of the white matter anatomy. Neuroimage. 2010;52:1289–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ceritoglu C, Oishi K, Li X, Chou MC, Younes L, Albert M, Lyketsos C, van Zijl PCM, Miller MI, Mori S. Multi-contrast large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping for diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2009;47:618–627. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Durrleman S, Prastawa M, Korenberg JR, Joshi S, Trouve A, Gerig G. Topology preserving atlas construction from shape data without correspondence using sparse parameters. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2012;15:223–230. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-33454-2_28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, Pennell DJ, Rumberger JA, Ryan T, Verani MS American Heart Association Writing Group on Myocardial Segmentation and Registration for Cardiac Imaging. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105:539–542. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinert-Threlkeld S, Ardekani S, Mejino JLV, Detwiler LT, Brinkley JF, Halle M, Kikinis R, Winslow RL, Miller MI, Ratnanather JT. Ontological labels for automated location of anatomical shape differences. J Biomed Inform. 2012;45:522–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vadakkumpadan F, Arevalo H, Ceritoglu C, Miller M, Trayanova N. Image-based estimation of ventricular fiber orientations for personalized modeling of cardiac electrophysiology. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2012;31:1051–1060. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2012.2184799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ardekani S, Weiss RG, Lardo AC, George RT, Lima JAC, Wu KC, Miller MI, Winslow RL, Younes L. Computational method for identifying and quantifying shape features of human left ventricular remodeling. Ann Biomed Eng. 2009;37:1043–1054. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9677-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fischl B, Sereno MI, Tootell RB, Dale AM. High-resolution intersubject averaging and a coordinate system for the cortical surface. Hum Brain Mapp. 1999;8:272–284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:4<272::AID-HBM10>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nain D, Haker S, Bobick A, Tannenbaum A. Multiscale 3-D shape representation and segmentation using spherical wavelets. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26:598–618. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.893284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Essen DC, Drury HA. Structural and functional analyses of human cerebral cortex using a surface-based atlas. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7079–7102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-07079.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beg MF, Miller MI, Trouve A, Younes L. Computing large deformation metric mappings via geodesic flows of diffeomorphisms. Int J Comput Vis. 2005;61:139–157. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alexander DC, Gee JC, Bajcsy R. Strategies for data reorientation during non-rigid warps of diffusion tensor images. Proc Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv MICCAI’99. 1999;1679:463–472. [Google Scholar]