Hemichordate genomes and deuterostome origins (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2016 Jan 27.

Published in final edited form as: Nature. 2015 Nov 18;527(7579):459–465. doi: 10.1038/nature16150

Abstract

Acorn worms, also known as enteropneust (literally, ‘gut-breathing’) hemichordates, are marine invertebrates that share features with echinoderms and chordates. Together, these three phyla comprise the deuterostomes. Here we report the draft genome sequences of two acorn worms, Saccoglossus kowalevskii and Ptychodera flava. By comparing them with diverse bilaterian genomes, we identify shared traits that were probably inherited from the last common deuterostome ancestor, and then explore evolutionary trajectories leading from this ancestor to hemichordates, echinoderms and chordates. The hemichordate genomes exhibit extensive conserved synteny with amphioxus and other bilaterians, and deeply conserved non-coding sequences that are candidates for conserved gene-regulatory elements. Notably, hemichordates possess a deuterostome-specific genomic cluster of four ordered transcription factor genes, the expression of which is associated with the development of pharyngeal ‘gill’ slits, the foremost morphological innovation of early deuterostomes, and is probably central to their filter-feeding lifestyle. Comparative analysis reveals numerous deuterostome-specific gene novelties, including genes found in deuterostomes and marine microbes, but not other animals. The putative functions of these genes can be linked to physiological, metabolic and developmental specializations of the filter-feeding ancestor.

The prominent pharyngeal gill slits, rigid stomochord, and midline nerve cords of acorn worms led 19th century zoologists to designate them as ‘hemichordates’ and group them with vertebrates and other chordates1–4, but their early embryos and larvae also linked them to echinoderms5,6. Current molecular phylogenies strongly support the affinities of hemichordates and echinoderms as sister phyla, together called ambulacrarians7, and unite ambulacrarians and chordates within the deuterostomes (see glossary in Supplementary Note 1). Of all the shared derived morphological characters proposed between hemichordates and chordates, the pharyngeal gill slits have emerged with unambiguous morphological and molecular support, notably the shared expression of the pax1/9 gene8–10. These structures were ancestral deuterostome characters elaborated upon the bilaterian ancestral body plan, but the gill slits were subsequently lost in extant echinoderms and amniotes11. Since extant invertebrate deuterostomes use this apparatus for efficient suspension and/or deposit feeding, the early Cambrian or Precambrian deuterostome ancestor probably also shared this lifestyle. This perspective on the last common deuterostome ancestor informs our understanding of the subsequent evolution of hemichordates, echinoderms and chordates10,12–16.

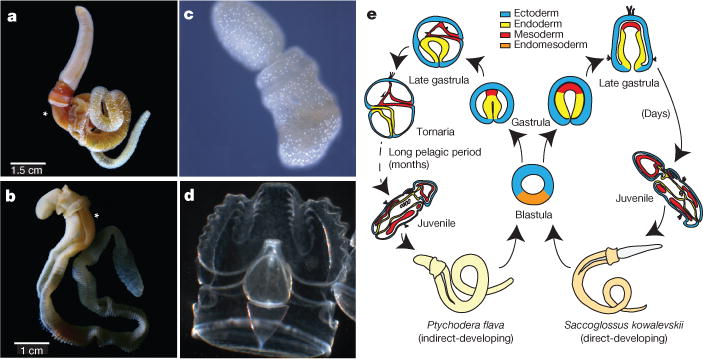

Hemichordates share bilateral symmetry, gill slits, soft bodies and early axial patterning with chordates, making them key comparators for inferring the ancestral genomic features of deuterostomes. To this end, we sequenced and analysed the genomes of acorn worms belonging to the two main lineages of enteropneust hemichordates (Supplementary Note 1): Saccoglossus kowalevskii (Harrimaniidae; Atlantic, North America, Fig. 1a) and Ptychodera flava (Ptychoderidae; Pacific, pantropical, Fig. 1b). Both have characteristic three-part bodies comprising proboscis, collar and trunk, the last with tens to hundreds of pairs of gill slits. While S. kowalevskii develops directly to a juvenile worm with these traits within days (Fig. 1c, e), P. flava develops indirectly through a feeding larva that metamorphoses to a juvenile worm after months in the plankton (Fig. 1d, e). Our analyses begin to integrate macroscopic information about morphology, organismal physiology, and descriptive embryology of these deuterostomes with genomic information about gene homologies, gene arrangements, gene novelties and non-coding elements.

Figure 1. Hemichordate model systems and their embryonic development.

The hemichordate phylum includes the enteropneusts (acorn worms) and pterobranchs (minute, colonial, tube-dwelling; not shown). a, c, Saccoglossus kowalevskii (Harrimaniid (direct developing) enteropneust) adult (a) and juvenile (c) with gill slits. b, d, Ptychodera flava (Ptychoderid (indirect developing) enteropneust) adult (b) and the tornaria stage larva (d). Gill slits labelled with an asterisk in a and b. e, Comparison of the direct and indirect modes of development of the two hemichordates, indicating the long pelagic larval period in Ptychodera until the settlement and metamorphosis as a juvenile.

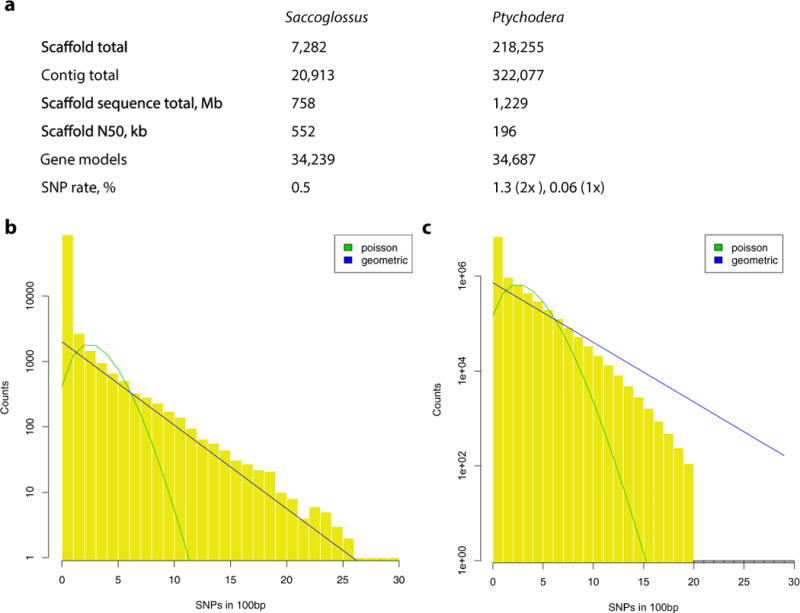

Genomes

We sequenced the two acorn worm genomes by random shotgun methods with a variety of read types (Methods; Supplementary Note 2), each starting from sperm from a single outbred diploid individual. The haploid lengths of the two genomes are both about 1 Gbp (Extended Data Fig. 1), but differ in nucleotide heterozygosity. Both acorn worm genomes were annotated using extensive transcriptome data as well as standard homology-based and de novo methods (Supplementary Note 3). Counting gene models with at least one detectable orthologue in another sequenced metazoan species, we find that Ptychodera and Saccoglossus encode at least 18,556 and 19,270 genes, respectively (Methods). Additional de novo gene predictions include divergent and/or novel genes (Extended Data Fig. 1). Despite the ancient divergence of the Saccoglossus and Ptychodera lineages (more than 370 million years ago, see below) and their different modes of development, the two acorn worm genomes have similar bulk gene content, as discussed later (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 4), and similar repetitive landscapes (Supplementary Note 5).

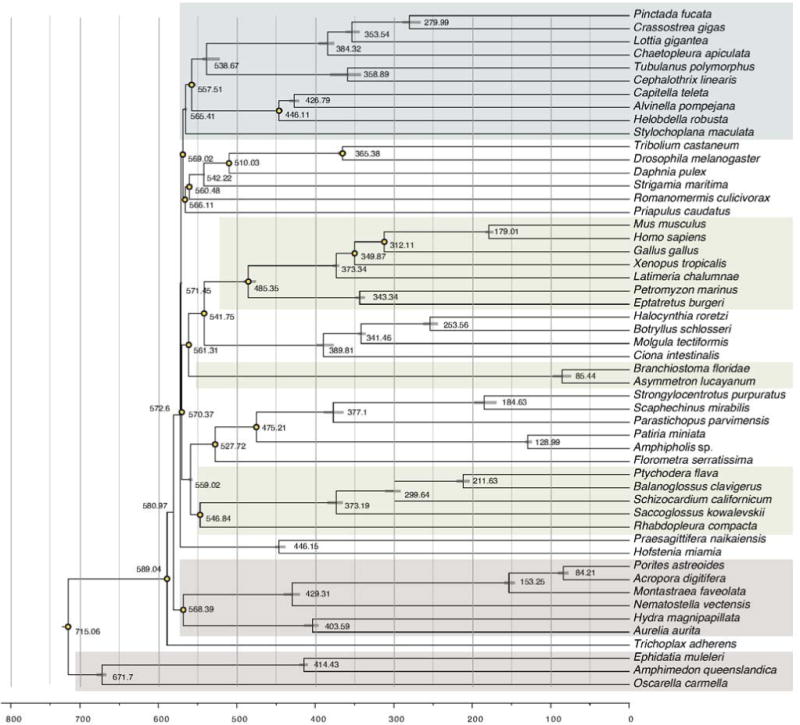

Deuterostome phylogeny

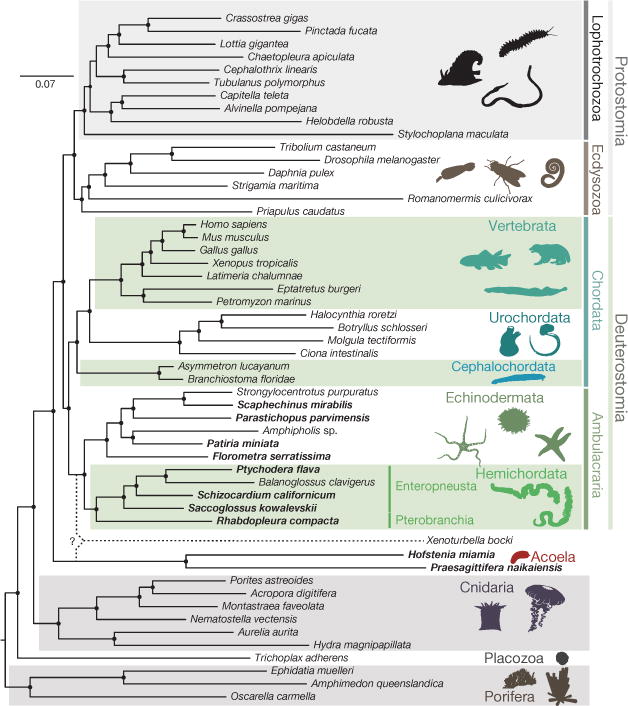

Deuterostome relationships were originally inferred from developmental and morphological characters2,5,17 and these hypotheses were later tested and refined with molecular data6,7. Aspects of deuterostome phylogeny continue to be controversial, however, notably the position of the sessile pterobranchs among hemichordates, and the surprising association of Xenoturbella18 and acoelomorph flatworms with ambulacrarians19 proposed by some studies. We explored these issues using genome-wide analyses of the newly sequenced hemichordate genomes augmented with extensive new RNAseq from five echinoderms, three additional hemichordates (including a rhabdopleurid pterobranch) and two acoels (Fig. 2, Extended Data Fig. 3, Methods and Supplementary Note 6). We recovered the monophyly of hemichordates, echinoderms, ambulacrarians and deuterostomes, using not only amino acid characters but also presence–absence characters for introns and coding indels (Supplementary Note 4). Our analyses also placed pterobranch hemichordates as the sister-group to enteropneusts7 rather than within them12. These phylogenetic analyses imply that genomic traits shared by chordates and ambulacrarians can be attributed to the last common deuterostome ancestor (see below). Using a relaxed molecular clock, we estimate a Cambrian origin of hemichordates (Methods, Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 6).

Figure 2. Phylogenetic placement of deuterostome taxa within the metazoan tree.

Maximum-likelihood tree obtained with a super-matrix of 506,428 amino-acid residues gathered from 1,564 orthologous genes in 52 species (65.1% occupancy) and using a LG+Γ model partitioned for each gene. Filled circles at nodes denote maximal bootstrap support. Taxa highlighted in bold are newly sequenced genomes and transcriptomes introduced in this study. Bar indicates the number of substitutions per site.

We also performed several analyses to assess the controversial relationships between Xenoturbella, acoelomorphs and deuterostomes (Supplementary Note 6). With conventional site-homogeneous models, acoels remain outside deuterostomes20–23 (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figs 6.1 and 6.2). Alternative models24, however, show equivocal branching of acoels depending on the inclusion of the current sparse data for Xenoturbella (Supplementary Note 6). Notably, without Xenoturbella, acoels are positioned as a bilaterian sister group (Supplementary Fig. 6.3)20–23. Although we cannot rule out a deuterostome placement for Xenoturbella, our analyses generally do not support a grouping of acoels with deuterostomes19.

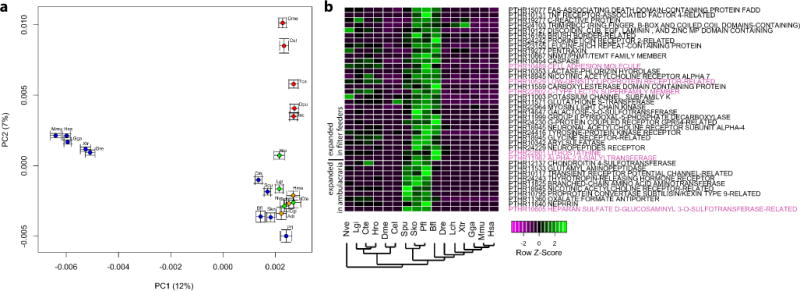

The gene set of the deuterostome ancestor

By comparative analysis, we identified 8,716 families of homologous genes whose distributions in sequenced extant genomes imply their presence in the deuterostome ancestor (Methods; Supplementary Note 4). Owing to gene duplication and other processes the descendants of these ancestral genes account for ~14,000 genes in extant deuterostome genomes including human (Supplementary Table 4.1.2). The distributions of gene functions, domain compositions, and gene family sizes of hemichordates resemble those of amphioxus, sea urchin, and sequenced lophotrochozoans more than those of ecdysozoans; vertebrates also form a distinct group (Extended Data Fig. 2, Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4.2).

Exon–intron structures of genes are generally well conserved among hemichordates, chordates, and many non-deuterostome metazoans, allowing us to infer 2,061 ancestral deuterostome splice sites (Supplementary Note 4). Among orthologous bilaterian genes we found 23 introns and 4 coding sequence indels present only in deuterostomes (shared between at least one ambulacrarian and chordate), suggesting that these shared derived characters may be useful to diagnose clade membership of new candidate organisms (Supplementary Note 4).

Based on whole-genome alignments, we identified 6,533 conserved non-coding elements (CNE) longer than 50 bp that are found in all of the five deuterostomes Saccoglossus, Ptychodera, amphioxus, sea urchin, and human (Methods; Supplementary Note 8). The identified CNEs overlap extensively with human long non-coding RNAs (3,611 CNE loci; 55%, Fisher’s exact test P value < 2.2 × 10−16). Those alignments usually do not exceed 250 bp (as has been reported among vertebrates25) and occur in clusters (Supplementary Note 8). Among these conserved sequences is a previously identified vertebrate brain and neural tube specific enhancer, located close to the sox14/21 orthologue in all five species26.

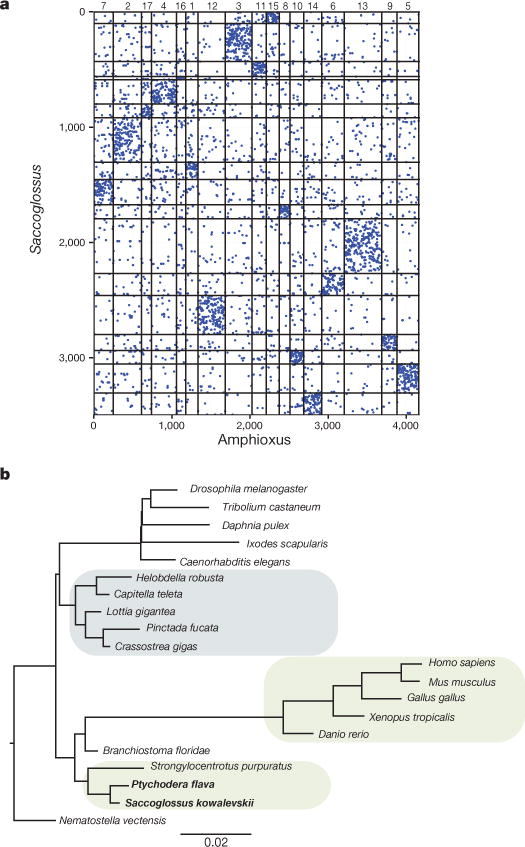

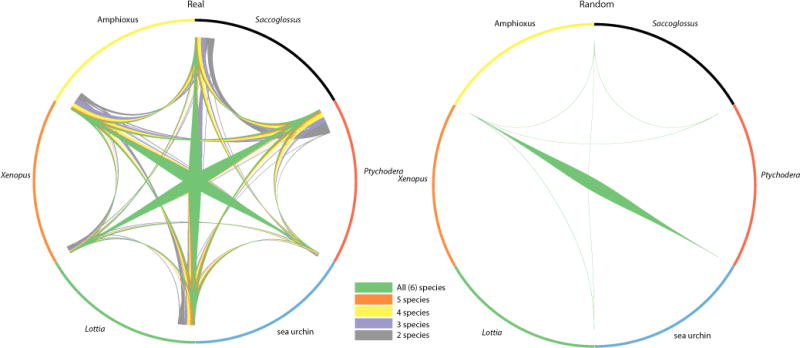

Conserved gene linkage

Ancient gene linkages (‘macro-synteny’27) are often preserved in extant bilaterian genomes27,28. Comparative analysis revealed 17 ancestral linkage groups across chordates, including amphioxus and Ciona27. While the contiguity of the draft of the sea urchin genome assembly29 is too limited to determine whether it shares this chromosome-scale organization, we find that the Saccoglossus genome clearly shares these chordate-defined linkage groups (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Note 7), implying that these chromosome-scale linkages were also present in the ancestral deuterostome.

Figure 3. High level of linkage conservation in Saccoglossus.

a, Macro-synteny dot plot between Saccoglossus and amphioxus; each dot represents two orthologous genes linked in the two species, and ordered according to their macro-syntenic linkage. Amphioxus scaffolds are organized according to the 17 ancestral linkage groups (ALGs) inferred by comparison of the amphioxus and vertebrate genomes27. Intersection areas of highest dot density are marked by numbers along the top of the plot, identifying each of the 17 putative ALGs. Axes represent orthologous gene group index along the genome. b, Branch-length estimation for loss and gain of synteny blocks with MrBayes, see Supplementary Note 7 for details. Short branches in hemichordates (in bold) indicate a high level of micro-syntenic retention in their genomes.

On a more local scale, we find hundreds of tightly linked conserved gene clusters of three or more genes (‘micro-synteny’; Methods; Supplementary Note 7) including Hox30 and ParaHox31 clusters in both acorn worms (Extended Data Fig. 4), as also found in echinoderms32,33. Saccoglossus and amphioxus share more micro-syntenic linkages with each other than either does with sea urchin, vertebrates, or available protostome genomes (Methods, Fig. 3b and Extended Data Figs 5 and 6). Conservation of micro-syntenic linkages can occur due to low rates of genomic rearrangement or, more interestingly, as a result of selection to retain linkages between genes and their regulatory elements located in neighbouring genes28.

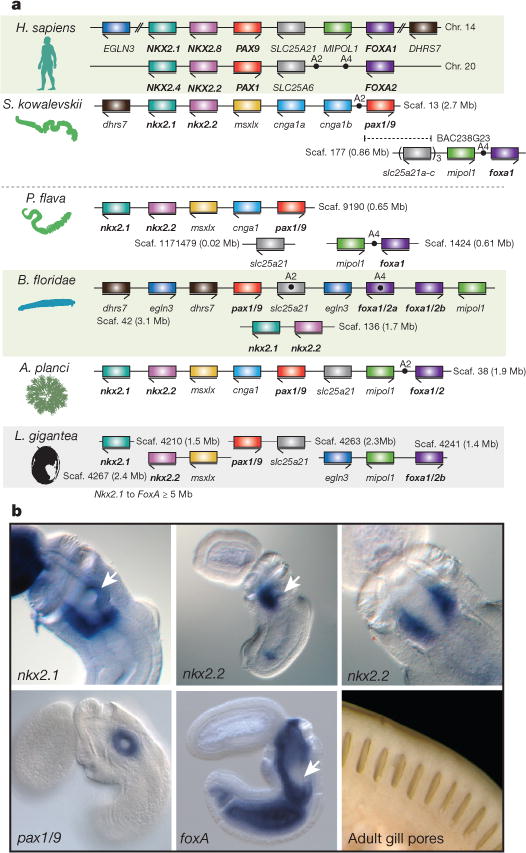

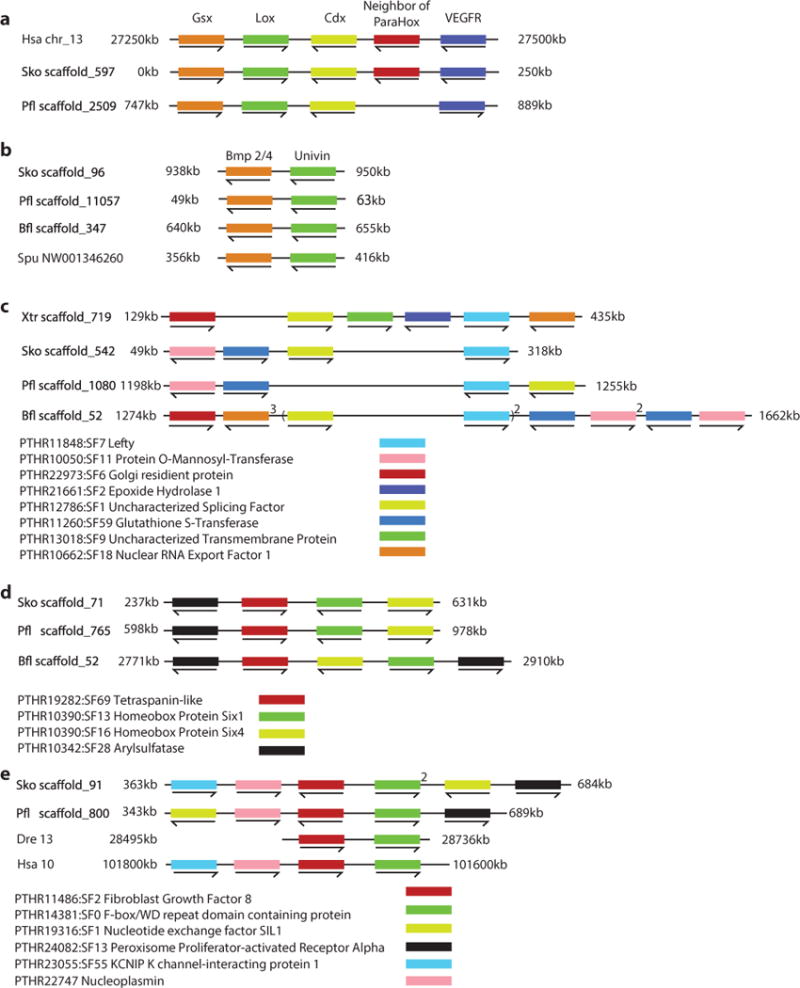

A deuterostome pharyngeal gene cluster

One conserved deuterostome-specific micro-syntenic cluster with functional implications for deuterostome biology is a cluster of genes expressed in the pharyngeal slits and surrounding pharyngeal endoderm (Fig. 4; Supplementary Note 9). This six-gene cluster contains four transcription factor genes in the order nkx2.1, nkx2.2, pax1/9 and foxA, along with two non-transcription-factor genes slc25A21 and mipol1, whose introns harbour regulatory elements for pax1/9 and foxA, respectively34–36. The cluster was first found conserved across vertebrates including humans (see chromosome 14; 1.1 Mb length from nkx2.1 to foxA1)34,37. In S. kowalevskii, it is intact with the same gene order as in vertebrates (0.5 Mb length from nkx2.1 to foxA), implying that it was present in the deuterostome and ambulacrarian ancestors. The full ordered gene cluster also exists on a single scaffold in the crown-of-thorns sea star Acanthaster planci. Since these genes are not clustered in available protostome genomes, there is no evidence for deeper bilaterian ancestry. Two non-coding elements that are conserved across vertebrates and amphioxus38 are found in the hemichordate and A. planci clusters at similar locations (A2 and A4, in Fig. 4a).

Figure 4. Conservation of a pharyngeal gene cluster across deuterostomes.

a, Linkage and order of six genes including the four genes encoding transcription factors Nkx2.1, Nkx2.2, Pax1/9 and FoxA, and two genes encoding non-transcription factors Slc25A21 (solute transporter) and Mipol1 (mirror-image polydactyly 1 protein), which are putative ‘bystander’ genes containing regulatory elements of pax1/9 and foxA, respectively. The pairings of slc25A21 with pax1/9 and of mipol1 with foxA occur also in protostomes, indicating bilaterian ancestry. The cluster is not present in protostomes such as Lottia (Lophotrochozoa), Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans (Ecdysozoa), or in the cnidarian, Nematostella. SLC25A6 (the slc25A21 paralogue on human chromosome 20) is a potential pseudogene. The dots marking A2 and A4 indicate two conserved non-coding sequences first recognized in vertebrates and amphioxus36, also present in S. kowalevskii and, partially, in P. flava and A. planci. b, The four transcription factor genes of the cluster are expressed in the pharyngeal/foregut endoderm of the Saccoglossus juvenile: nkx2.1 is expressed in a band of endoderm at the level of the forming gill pore, especially ventral and posterior to it (arrow), and in a separate ectodermal domain in the proboscis. It is also known as thyroid transcription factor 1 due to its expression in the pharyngeal thyroid rudiment in vertebrates. The nkx2.2 gene is expressed in pharyngeal endoderm just ventral to the forming gill pore, shown in side view (arrow indicates gill pore) and ventral view; and pax1/9 is expressed in the gill pore rudiment itself. In S. kowalevskii, this is its only expression domain, whereas in vertebrates it is also expressed in axial mesoderm. The foxA gene is expressed widely in endoderm but is repressed at the site of gill pore formation (arrow). An external view of gill pores is shown; up to 100 bilateral pairs are present in adults, indicative of the large size of the pharynx.

The pax1/9 gene, at the centre of the cluster, is expressed in the pharyngeal endodermal primordium of the gill slit in hemichordates, tunicates, amphioxus, fish, and amphibians8,9, and in the branchial pouch endoderm of amniotes (which do not complete the last steps of gill slit formation), as well as other locations in vertebrates. The nkx2.1 (thyroid transcription factor 1) gene is also expressed in the hemichordate pharyngeal endoderm in a band passing through the gill slit, but not localized to a thyroid-like organ39. Here we also examined the expression of nkx2.2 and foxA in S. kowalevskii. We find that nkx2.2, which is expressed in the ventral hindbrain in vertebrates, is expressed in pharyngeal ventral endoderm in S. kowalevskii, close to the gill slit (Fig. 4b), and that foxA is expressed throughout endoderm but repressed in the gill slit region (Fig. 4b). The co-expression of this ordered cluster of the four transcription factors during pharyngeal development strongly supports the functional importance of their genomic clustering.

The presence of this cluster in the crown-of-thorns sea star, an echinoderm that lacks gill pores, and in amniote vertebrates that lack gill slits, suggests that the cluster’s ancestral role was in pharyngeal apparatus patterning as a whole, of which overt slits (perforations of apposed endoderm and ectoderm) were but one part, and the cluster is retained in these cases because of its continuing contribution to pharynx development. Genomic regions of the pharyngeal cluster have been implicated in long-range promoter–enhancer interactions, supporting the regulatory importance of this gene linkage (see Supplementary Note 9)40. Alternatively, genome rearrangement in these lineages may be too slow to disrupt the cluster even without functional constraint. Here we propose that the clustering of the four ordered transcription factors, and their bystander genes, on the deuterostome stem served a regulatory role in the evolution of the pharyngeal apparatus, the foremost morphological innovation of deuterostomes.

Deuterostome novelties

We found > 30 deuterostome genes with sequences that differ markedly from those of other metazoans, related to functional innovation in deuterostomes. Some plausibly arose from accelerated sequence change on the deuterostome stem from distant but identifiable bilaterian homologues, others represent new protein domain combinations in deuterostomes, while others lack identifiable sequence and domain homologues in other animals. In the latter group, we found over a dozen deuterostome genes that have readily identified relatives in marine microbes, often cyanobacteria or eukaryotic micro-algae, but are not known in other metazoans (Extended Data Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 7; Supplementary Notes 10.4 and 10.5). Such genes include two of the novel deuterostome sequences associated with sialic acid metabolism (found in many microbes41, see below), enzymes that modify proteins (for example, protein arginine deiminase) and RNA (for example, FATSO methyladenosine demethylase) as well as others that provide specialized reactions of secondary metabolism (Extended Data Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 7; Supplementary Note 10.5). Possible explanations for the unusual phylogenetic distribution of these genes include horizontal transfer on the deuterostome stem from early marine microbes (which were plausibly commensals, pathogens, or food sources of stem deuterostomes), or convergent gene loss and/or extensive sequence divergence along five or more opisthokont lineages (Supplementary Note 10.2).

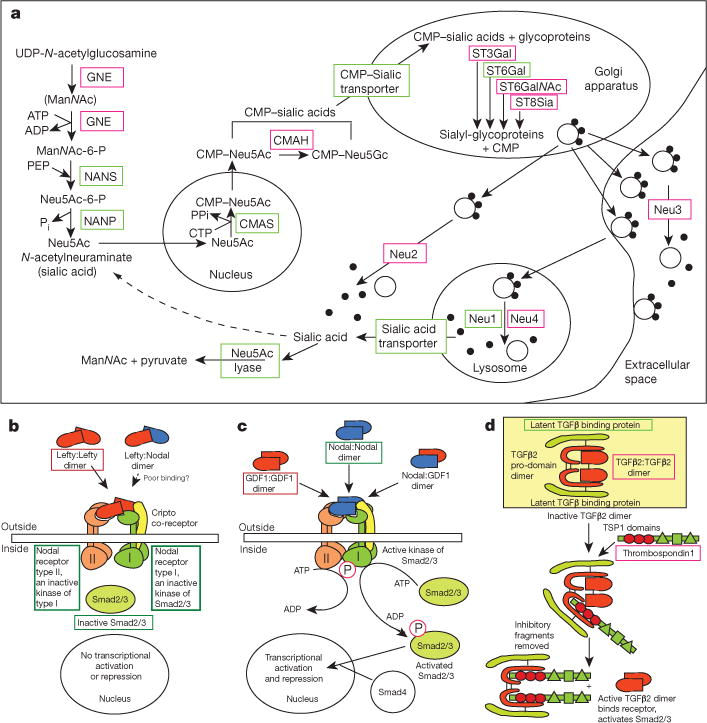

Regardless of their mechanism of origination, the various deuterostome novelties and gene family expansions of sialic acid metabolism are noteworthy. Deuterostomes are unique among metazoans in their high level and diverse linkage of addition of sialic acid (also known as neuraminic acid), a nine carbon negatively charged sugar, to the terminal sugars of glycoproteins, mucins and glycolipids42. We find expanded families of enzymes for several of these reactions in hemichordates (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Table 1). Based on the presence/absence of relevant enzymes we infer that 5 of the 11 steps of the pathways of sialic acid formation, addition to termini, and removal are not found in protostomes or other metazoans, and are deuterostome novelties (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Note 10), whereas the other steps use enzymes similar to those of the more limited pathway of some protostomes (for example, insects such as Drosophila)43.

Figure 5. Examples of deuterostome gene novelties.

a, Steps of biosynthesis of sialic acid and its addition to and removal from glycoproteins. b–d, Novel genes in TGFβ signalling pathways. The encoded proteins are shown and include Lefty (b), an antagonist of Nodal signalling, which activates Smad2/3-dependent transcription when not antagonized; Univin (c), an agonist of Nodal signalling, also called Vg1, DVR1, and GDF1; and TGFβ 2 (d), a ligand that act ivates Smad2/3-dependent transcription by binding to a deuterostome-specific TGFβ receptor type II, which contains a novel ectodomain (not shown). Also shown in d is the novel protein thrombospondin 1 that activates TGFβ 2 by releasing it from an inactive complex, by way of its TSP1 domains. Red boxes around protein names indicate their deuterostome novelty. Green boxes around the names indicate genes with pan-metazoan/bilaterian ancestry and without accelerated sequence change in the deuterostome lineage.

The importance of glycoproteins for muco-ciliary feeding and other hemichordate activities is further supported by novel and expanded families of genes encoding the polypeptide backbones of glycoproteins, those with von Willebrand type-D and/or cysteine-rich domains (PTHR11339 classifier), including mucins, present in hemichordates and amphioxus as large tandemly duplicated clusters (with varied expression patterns as shown in Extended Data Fig. 8), but not in sea urchin, which has a different mode of feeding (Supplementary Note 10). As in amphioxus, the pharynx of Saccoglossus is heavily ciliated44,45, and cells of the pharyngeal walls in hemichordates and the ventral endostyle in amphioxus secrete abundant mucins and glycoproteins46. Similarly, in the deuterostome ancestor these glycoproteins probably enhanced the muco-ciliary filter-feeding capture of food particles from the microbe-rich marine environment and protected its inner and outer tissue surfaces.

Novelty in the TGFβ signalling pathway

The signalling ligands Lefty (a Nodal antagonist) and Univin/Vg1/GDF147 (a Nodal agonist) are deuterostome innovations that modulate Nodal signalling during the major developmental events of endomesoderm induction and axial patterning in vertebrates, axial patterning in hemichordates and echinoderms, and left–right patterning in all deuterostomes48 (see Fig. 5b–d and Extended Data Fig. 9a, b). Univin is tightly linked to the related bilaterian bmp2/4 in the sea urchin genome49 and also, we now report, in hemichordates and amphioxus, supporting its origin by tandem duplication and divergence from an ancestral _bmp2/4_-type gene, as suggested previously49.

TGFβ 2 signalling (TGFβ 1, 2 and 3 in vertebrates) is a deuterostome innovation that controls cell growth, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis at later developmental stages. Accompanying the novel TGFβ 2 ligand, the type II receptor has a novel ectodomain. The extracellular matrix protein thrombosp ondin 1, which activates TGFβ 2 in vertebrates, contains a deuterostome-unique combination of domains including three thrombospondin type 1 (TSP1) domains that bind the TGFβ 2 pro-domain region. While these signalling novelties have clear sequence similarity to pan-bilaterian components, they form long stem branch clades on the phylogenetic trees, indicating extensive sequence divergence on the deuterostome stem (Supplementary Note 10). Together, these innovations appear to contribute to the increased amount and complex patterning of Smad2/3-mediated signalling in deuterostomes compared with protostomes and other metazoans.

Conclusion

The two acorn worms whose genomes are described here represent the two main enteropneust lineages, separated by at least 370 million years and differing in their developmental modes. These analyses reveal (1) extensive conserved macro-synteny among deuterostomes; (2) a widely conserved deuterostome-specific cluster of six ordered genes, including four transcription factor genes that are expressed during the development of pharyngeal gill slits and the branchial apparatus, the most prominent morphological innovation of the deuterostome ancestor; and (3) numerous gene novelties shared among deuterostomes, many expanded into large families, with putative protein functions that imply physiological, metabolic and developmental specializations of the filter-feeding deuterostome ancestor. Some of these genes lack identifiable orthologues in other metazoans but do resemble microbial sequences and domain types. In addition to their contributions towards defining the deuterostome ancestor and illuminating chordate origins, the two genomes should inform hypotheses of larval evolution by providing a basis for future comparisons of direct-developing and indirect-developing acorn worms, which achieve remarkably similar adult forms by distinct embryological routes (Fig. 1).

METHODS

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Sequencing

Sperm DNA from adult males was extracted for sequencing as described in Supplementary Note 2. A single male was used for each species to minimize the impact of heterozygosity on assembly. For Saccoglossus, approximately eightfold redundant random shotgun coverage (totalling 8.1 Gb) was obtained with Sanger dideoxy sequencing at the Baylor College of Medicine Genome Center, including 34,279 BAC ends and 459,052 fosmid ends. For Ptychodera, 1.3 Gb in Sanger shotgun sequences, 15.3 Gb in Roche 454 pyrosequence reads, and 52-Gb paired-end sequences with Illumina MiSeq, along with mate-pairs, were generated at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University. More sequencing details are available in Supplementary Note 2.

Genome assemblies

We assembled the Saccoglossus genome with Arachne50, combined with BAC/fosmid pair information to produce the final assembly. This Saccoglossus assembly includes 7,282 total scaffold sequences spanning a total length of 758 Mb. The relatively modest nucleotide heterozygosity (0.5%) of S. kowalevskii, coupled with longer read lengths, enabled assembly of a single composite reference sequence. Half of the assembly is in scaffolds longer than 552 kb (the N50 scaffold length), and 82% of the assembled sequence is found in 1,602 scaffolds longer than 100 kb. For Ptychodera we used the Platanus51 assembler. The resulting total scaffold length was 1,229 Mb, with half the assembly in scaffolds longer than 196 kb (N50 scaffold length). P. flava exhibited a notably higher heterozygosity (1.3% single nucleotide heterozygosity with frequent indels) than S. kowalevskii, presumably related to its pelagic dispersal and larger effective population size52. We therefore initially produced stringent separate assemblies of the two divergent haplotypes, and found that many scaffolds had a closely related second scaffold with ~94% BLASTN identity (over longer stretches, including indels). To avoid reporting both haplotypes at these loci, scaffolds with less than 6% divergence over at least 75% of their length were merged into a single haploid reference for comparative analysis. To further classify regions with ‘double’ depth and single haplotype regions we implemented a Hidden Markov Model classifier. We find that at least 63% of the initial Platanus assembly constitutes merged haplotypes. The inferred SNP rate for those regions is 1.3%, while for the remaining haplotype regions it is below 0.1%. Further details of assemblies are described in Supplementary Note 2.

Gene predictions

Transcriptome data for both species were used, along with homology-guided and ab initio methods, to predict protein-coding genes (Supplementary Note 3). For Saccoglossus, 8.6 million RNAseq reads were generated from 7 adult tissues and 15 developmental stages using Roche 454 sequencing, along with previously deposited ESTs in GenBank. For Ptychodera, extensive EST data from egg, blastulae, gastrulae, larvae, juveniles, adult proboscis, stomochord, and gills defining 34,159 cDNA clones53, and 879,000 Roche/454 RNAseq reads from a mixed library of developmental stages54 were used. The Saccoglossus genome was annotated using JGI gene prediction pipeline55, while Augustus56 was used to produce gene models for Ptychodera. We find a total of 34,239 gene predictions for Saccoglossus (68% with transcript evidence) and 34,687 for Ptychodera (43% with transcript evidence), although these are overestimates of the true gene number due to fragmented gene predictions, mis-annotated repetitive sequences, and spurious predictions. As described in the main text, 18–19,000 gene models in each species have known annotations and/or orthologues in other species.

Gene family analysis

Gene family clustering was done using a progressive (leaf to root) BLASTP-based clustering algorithm, where at a given phylogenetic node the gene families are constructed taking into account protein similarities among ingroups and outgroups57. For the inference of deuterostome gene families we use the bilaterian node of the clustering. To call gene families present in the deuterostome ancestor, we required (1) at least two ambulacrarian orthologues out of the three available ambulacrarian genomes and at least two chordate orthologues, or (2) at least two deuterostomes (chordates and/or ambulacrarians) and two outgroups in the bilaterian level clusters.

Transposable elements

Repetitive sequences were identified using RepeatScout58, followed by manual curation and annotation using both a Repbase release (version 20140131)59 and BLASTX-based search against a custom collection of transposons, using a previously described repeat identification and annotation pipeline57 (Supplementary Note 5). The assemblies were then masked with RepeatMasker version open-4.0.560. The repetitive complements of the two hemichordate genomes are summarized in Supplementary Table 5.1.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analyses were done using metazoan-level gene family clusters based on whole-genome sequences (Supplementary Note 4), selecting a single orthologue per genome with the best cumulative BLASTP to other species, and best reciprocal BLASTP hits to species with transcriptome-only information (Supplementary Note 6). Single gene alignments were built using Muscle61 and filtered using Trimal62 for each orthologue, and were concatenated, yielding a supermatrix of 506,428 positions with 34.9% missing data. This super-matrix was analysed with ExaML assuming a site-homogenous LG+Γ 4 model partitioned for each gene63. A slow-fast analysis was conducted to stratify marker genes based on the length of the branch leading to acoels in individual trees. A subset of the slowest 10% of genes was analysed with the site-heterogenous CAT+ GTR+Γ4 model using Phylobayes24. Molecular dating was carried out using Phylobayes24 using the log-normal relaxed clock model and the calibrations described in Supplementary Table 6.2.

Synteny analysis

Macro- and micro-syntenic linkages were calculated as described in Supplementary Note 7. For Fig. 3a, we merged the amphioxus scaffolds into 17 pre-defined scaffold groups as suggested in ref. 27. These 17 merged scaffold groups represent the 17 ancestral linkage groups (ALGs) shared in chordates. Then we calculated the orthologous gene groups shared by each amphioxus ALG-Saccoglossus scaffold pair and generated the dot plot as described in Supplementary Note 7. For micro-synteny we required at least three genes (separated by a maximum of ten genes) to be present in pairwise comparisons. Under random reshuffling of the genome, this yields 10% false positives in pairwise genome comparisons, that is, we observe approximately one-tenth as many micro-syntenic blocks between the two genomes when gene orders are shuffled. This false-positive rate, however, falls to 1% when considering more than two species. For our inference of deuterostome ancestral and novel synteny we therefore focus on blocks present in at least three species (and both ingroup representatives, that is, ambulacrarians and chordates). This yields 698 blocks that can be traced back to the deuterostome ancestor, including 71 blocks found exclusively in deuterostome species (shared among ambulacrarians and chordates), including the pharyngeal cluster discussed in Fig. 4.

Whole-genome alignment

Whole-genome alignments were conducted with MEGABLAST64 using parameters previously reported65. We assessed the distribution of the resulting 12,722 aligned loci across known gene annotations in ENSEMBL66, previously identified conserved pan-vertebrate elements65, as well as known enhancers in human according to LBL database67.

Gene novelties

Deuterostome gene novelties were assessed initially through bilaterian gene clusters (Supplementary Note 10) by requiring at least two species on both ambulacrarian and chordate side to be present. The novelties were further automatically subdivided into four categories: G1 (gain type I), with no BLASTP hit outside of deuterostomes; G2 (gain type II), with a novel PFAM domain present only in deuterostomes; G3 (gain type III) having a novel PFAM combination unique to deuterostomes; and G4 (gain type IV), those that do not fall under any of the G1-3 categories and define novelties due to acceleration in the substitution rate on the deuterostome stem. To confirm the novel nature, especially for G4 novelties, we have constructed phylogenies for the members and non-deuterostome BLASTP hits (up to an _e_-value of 1 × 10−20) using MAFFT-alignment-based FastTree calculations. The trees were assessed for the accelerated rate of evolution at the deuterostome stem (Supplementary Fig. 9.1.1). The final result is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Curation of candidates for horizontal gene transfer on the deuterostome stem

We examined in detail gene families found broadly in deuterostomes whose encoded peptides were readily alignable to microbial sequences but had no detectable similarity in non-deuterostome animals. Criteria for evaluation included: (1) the hemichordate gene matches microbial genes at least ten orders of magnitude in the _e_-value better than it matches sequences of non-deuterostome metazoans (most of the putative HGTs we describe have no non-deuterostome metazoan hit at all); (2) it has a defined genomic locus among bona fide metazoan genes; (3) it shares an exon-intron structure with genes of chordates and other ambulacraria; and (4) when a low bitscore match is found to a non-deuterostome metazoan sequence, that sequence is identified as containing different domains (domain structure according to CDD68) and/or different exon-intron structure, implying dubious relatedness. When phylogenetic trees are constructed for these HGT-candidate proteins, the trees contain numerous branches for microbial sequences and none for non-deuterostome metazoan sequences, or only very long branches for dubiously relatives, and hence the trees differ greatly from the metazoan species tree, except within the deuterostome clade.

Code availability

Original data and code can be accessed at https://groups.oist.jp/molgenu.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Summary of genome assemblies and heterozygosity distributions for Saccoglossus and Ptychodera.

a, Genome statistics summary. b, c, The single nucleotide polymorphism distribution across 100-bp windows for Saccoglossus (b) and the corresponding distribution for Ptychodera (c). The distributions in b and c are fitted with a geometric (expected when high recombination rate is present) and a Poisson distribution (expected with low recombination rate). The distribution for Saccoglossus is fitted to windows with one or more SNPs only, as there is an excess of zero SNP windows (approximately 84% of total 94,324 selected windows). For methods refer to Supplementary Note 2.

Extended Data Figure 2. Ambulacrarians approximate the ancestral metazoan gene repertoire.

a, Principal component analysis of Panther gene family sizes. Variances of the first two components are plotted in parentheses. Blue indicates deuterostomes; green indicates lophotrochozoans; red, ecdysozoans; yellow/orange, non-bilaterian metazoans. Note the clustering of the ambulacrarians Sko, Pfl and Spu with the non-vertebrate deuterostomes Bfl and Cin in the lower right corner, also with the lophotrochozoans Cgi, Lgi, Hro, Cte and the non-bilaterians Hma, Nve and Adi. b, Heat map of gene family counts showing significant (Fisher’s exact test P value <0.01 after Bonferroni multiple testing correction) expansion in ambulacrarians as well as in Saccoglossus/Ptychodera/amphioxus. The cases discussed in the main text are highlighted in red. See Supplementary Note 4 for details. Species abbreviations are defined in Supplementary Note 4.1.

Extended Data Figure 3. Molecular dating of deuterostome and metazoan radiations using PhyloBayes assuming a log-normal relaxed clock model.

Yellow circles on particular nodes indicate the calibration dates applied from the fossil record, as indicated in Supplementary Note 6.2. Bars are 95% credibility intervals derived from posterior distributions. Note the estimated times of divergence of chordates and ambulacraria (the deuterostome ancestor) at 570 million years ago (Ma; mid-Ediacaran), hemichordates and echinoderms at 559 Ma, enteropneusts and pterobranchs at 547 Ma, and Harrimaniid and Ptychoderid enteropneusts at 373 Ma.

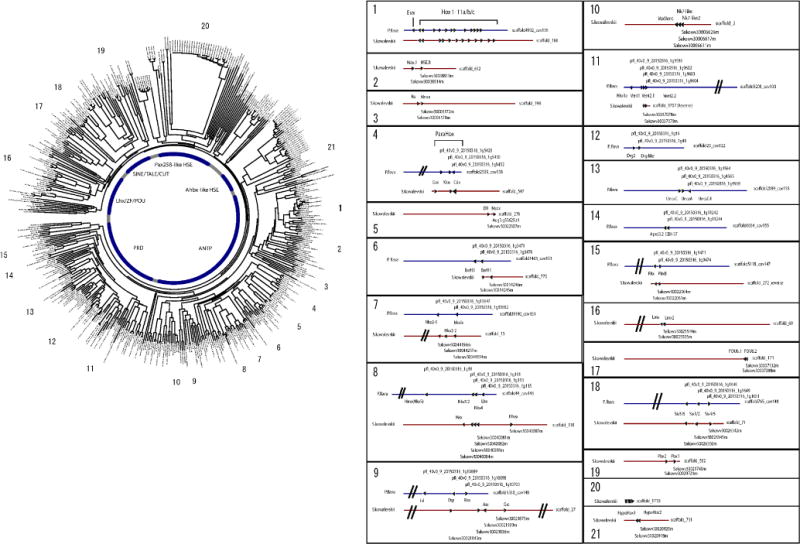

Extended Data Figure 4. Homeobox gene complement of the two hemichordates in comparison to that of amphioxus. The numbers of homeobox-containing gene models are 170 in Saccoglossus and 139 in Ptychodera.

These homeobox domains were aligned with 128 homeobox genes of Branchiostoma floridae using ClustalW2, then gaps and unaligned regions were manually removed. Since some genes have more than one homeobox domain, we kept all domains or chose the longest one according to the state of domain conservation. In total, 448 homeobox sequences were aligned. See Supplementary Information for details. The clusters of homeobox genes on scaffolds in Saccoglossus and Ptychodera were identified and drawn at positions around the tree. Conserved clusters between the two species were aligned. In addition to the well-known Hox and ParaHox cluster, 17 clusters were found in at least one of the hemichordates or some in both. Sixteen genes of the Nkx class are distributed over four clusters: (i) _nkx1a_-_vent1_-_vent2.1_-vent2.2; (ii) _nkx2.1_-_nkx2.2_-msxlx; (iii) _nkx5_-_msx_-_nkx3.2_-_nkx4_-_lbx_-hex; and (iv) _voxvent_-_nk7like_-nk7like2. The second cluster (ii) of these is part of the pharyngeal cluster (Fig. 4). Another five-gene cluster consists of one Lim class homeobox gene and four PRD class homeobox genes; _isl_-_otp_-_rax_-_arx_-gsc. A cluster of _six3/6_-_six1/2_-six4/5 was found in both species, and a cluster of three unx genes was found only in P. flava. Ten more clusters were found containing two homeobox genes each. Notably, we found species-specific homeobox clusters in both species. Three remarkable clusters were found in S. kowalevskii in which 10, 12 and 5 homeobox-containing genes are tandem duplicated in scaffold_1710, _52 and _4796, respectively. We also found such clusters in P.flava in which 7, 4, 8 and 10 genes are aligned on scaffold 19451, scaffold 1398, scaffold 12422 and scaffold 154657, respectively. All homeobox genes identified in the genomes of the two hemichordates and amphioxus are listed in the Supplementary Table for Extended Data Fig. 4. This list includes some genes not containing a homeobox (for example, pax1/9) in cases where other family members do (for example, pax2).

Extended Data Figure 5. High retention rate of micro-synteny in Saccoglossus.

Circos plot showing micro-syntenic conservation in blocks of genes (_n_max = 10 and _n_min = 2) for six metazoan species for observed (left) and simulated (right) linkages. The width of connecting segments is proportional to the number of genes participating in the syntenic linkages (normalized by the total gene count). In this representation scaffolds are placed end-to-end, and adjacent scaffolds need not be from the same chromosome. While simulated data yields some blocks shared between pairs of species, few or no synteny blocks can be recovered among three or more species (Methods). Saccoglossus shows one of the highest retentions among the selected species (and the highest among the sequenced ambulacrarians). Xenopus (and vertebrates in general) have lost some micro-synteny due to whole-genome duplications and differential loss of paralogues. The matching between the hemichordate S. kowalevskii and the chordate amphioxus is highest, consistent with the fact that neither genome has undergone extensive gene loss (as have tunicates) or pseudo-tetraploidization with extensive loss of paralogues (as have vertebrates).

Extended Data Figure 6. Deuterostome specific micro-syntenic linkages.

a, b, Very tight linkages with no intervening genes. a, ParaHox cluster shown in S. kowalevskii, P. flava, and human. b, bmp2/4 and univin cluster in the hemichordates S. kowalevskii and P. flava, the sea urchin S. purpuratus, and the cephalochordate B. floridae. c–e, Loose micro-syntenic linkages with a maximum of five intervening genes: lefty (c), six1_–_six4 (d), and fgf8_–_fbxw (e)69 clusters. For c to e all species with micro-synteny are shown. Numbers above the genes indicate the copy number in the locus.

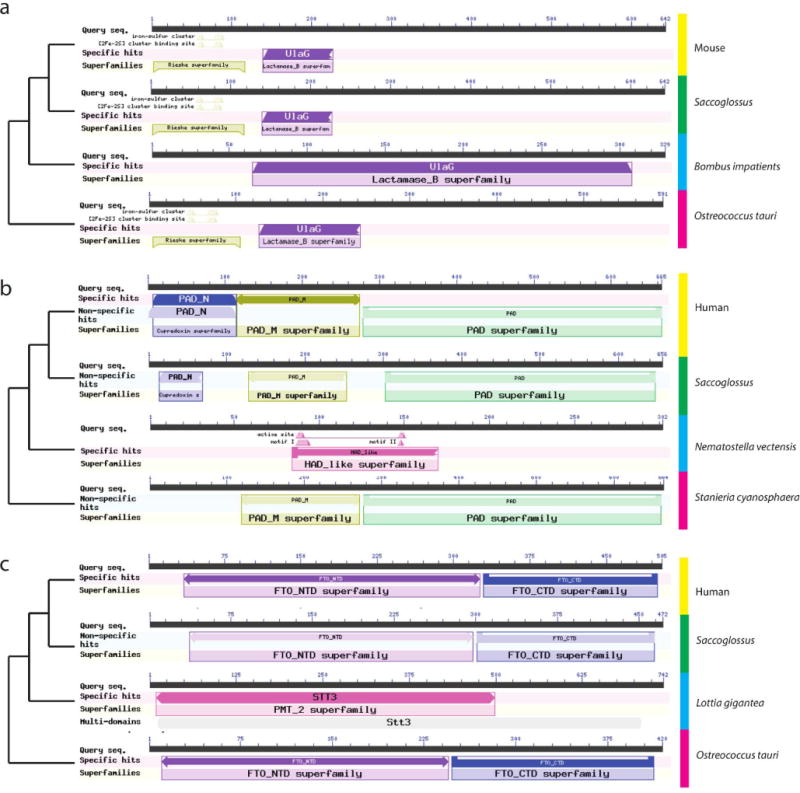

Extended Data Figure 7. Three examples showing the domain structures of some proteins encoded by genes found in deuterostomes and marine microbes but not non-deuterostome animals.

Best BLASTP hits of the Saccoglossus sequence in human/mouse, as well as in non-deuterostome metazoans and in non-metazoans (such as the cyanobacterium Staniera cyanosphaera, or the eukaryotic micro-alga Ostreococcus tauri) are shown. a, Cytidine monophosphate-_N_-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH), an enzyme of sialic acid modification; b, peptidyl arginyl deiminase (PAD), an enzyme of post-translational modification of proteins; c, FATSO-like, also called α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase FTO, an enzyme that de-methylates _N_6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA. Other analyses of these and other genes with the unusual phylogenetic distributions can be found in Supplementary Note 10.

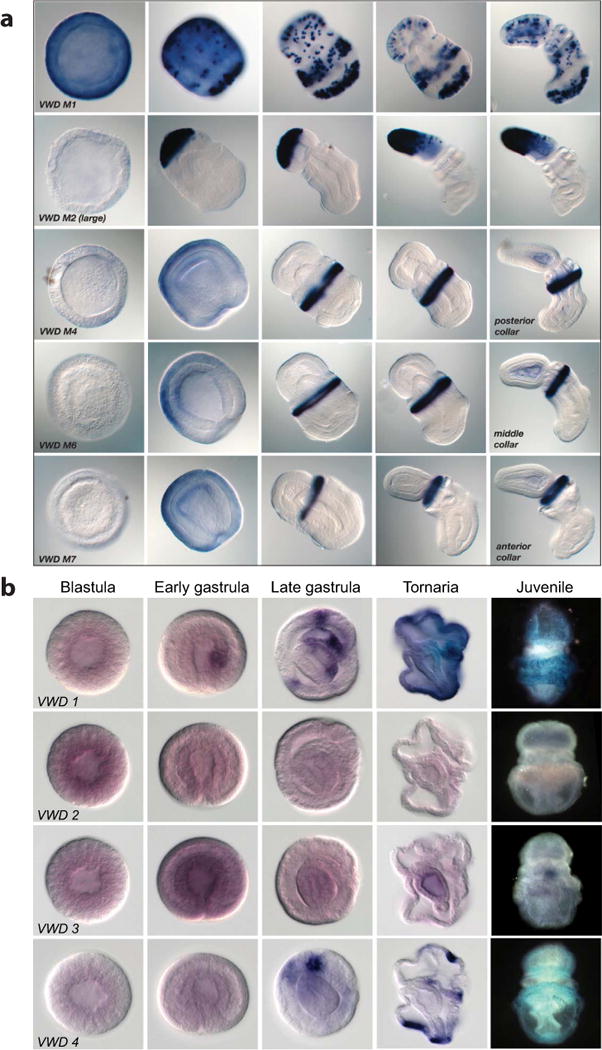

Extended Data Figure 8. In situ hybridization demonstration of the expression of von Willebrand type D (vWD) domain-encoding genes (putative glycoproteins/mucins) in Saccoglossus and Ptychodera.

a, In Saccoglossus the genes are specifically expressed in different subregions of the ectoderm of the proboscis or collar at these pre-feeding stages. b, In Ptychodera, several of the genes are expressed in endoderm as well as ectoderm of the developing tornaria larva. The sequence IDs for the genes are provided in Supplementary Note S10.4.

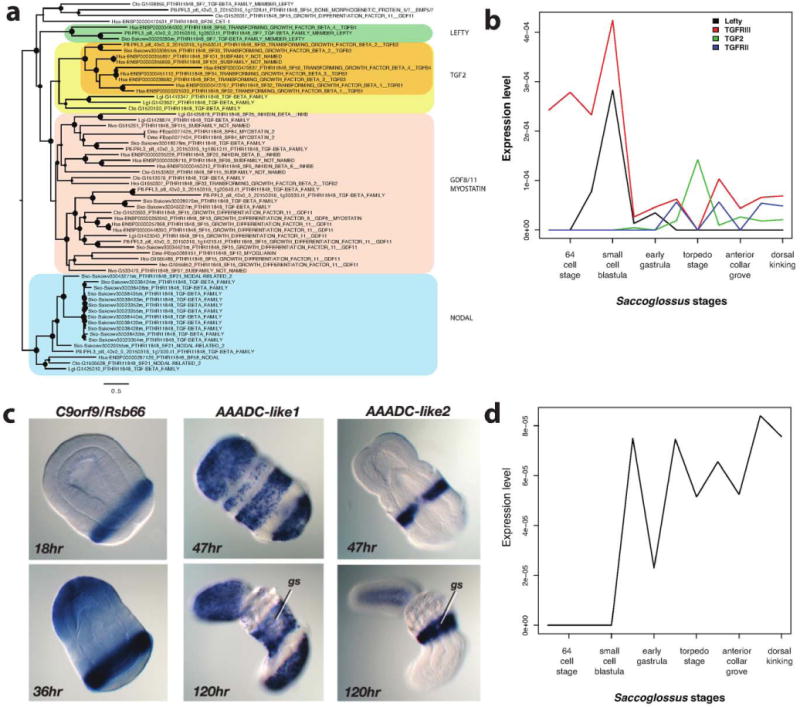

Extended Data Figure 9. Gene innovation in deuterostomes.

a, FastTree phylogenetic tree of the TGFβ family members Lefty, TGFβ 2, GDF8/11 and Nodal ligands (using GTR model). Bootstrap support is plotted as filled circles (size proportional to the support value) on each node. While Lefty shows deuterostome unique sequence composition, TGFβ 2 has an acceleration of sequence change at the deuterostome stem branch, compared to the GDF8/11 or Nodal groups. b, Temporal co-expression of Lefty and TGFβ receptor type III in Saccoglossus at pre-gastrulation developmental stages and of TGFβ 2 and TGFβ receptor type II at post-gastrulation stages. c, In situ hybridization demonstration of the expression in S. kowalevskii of one of the putative type I novelty genes (c9orf9, also known as rsb66) and of two of AAADC genes (aromatic amino acid decarboxylases of the microbial type) of S. kowalevskii (also in P. flava and B. floridae), which closely resemble sequences from bacteria rather than from non-deuterostome metazoans. gs, gill slits. d, The temporal expression profile for c9orf9 during S. kowalevskii development, taken from transcriptome data.

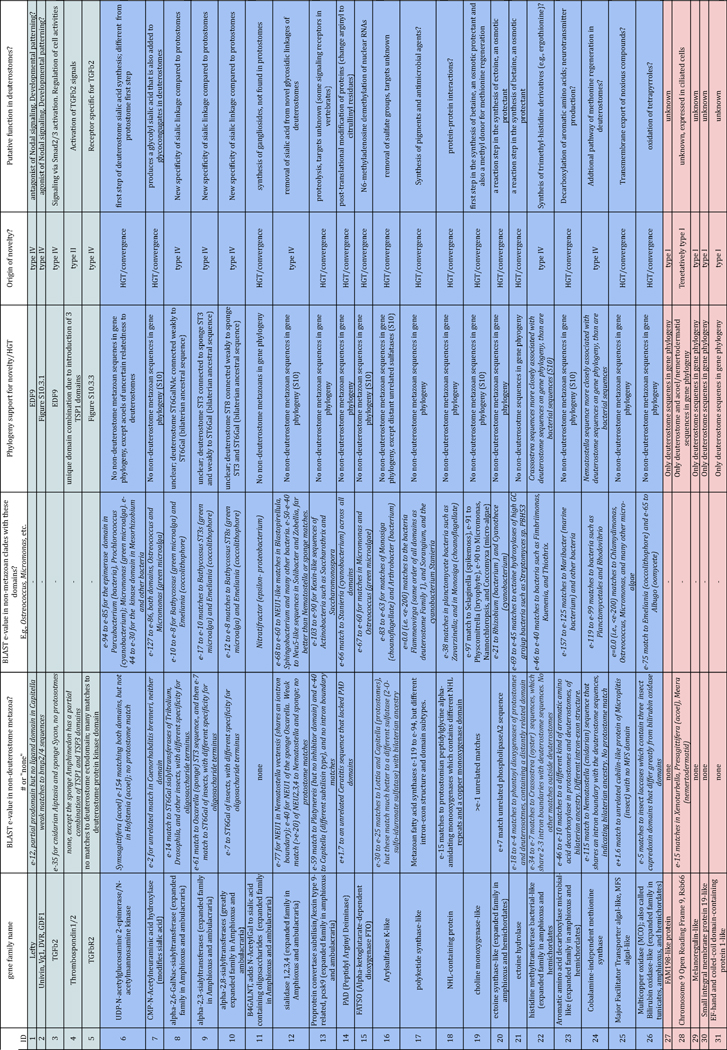

Extended data table 1.

Examples of deuterostome gene novelties and their genomic features

Supplementary Material

Information

data

data1

data2

Acknowledgments

The Ptychodera flava genome project was supported by MEXT and OIST, Japan. This research was supported by USPHS grant HD42724 and NASA grant FDNAG2–1605 to J.G.; USPHS grant HD37277 to M.W.K.; NASA – NNX13AI68G to C.L. F.M. was funded by FP7/ERC grant [268513]. O.S. and D.S.R, and T.K. and N.S. were supported by the Molecular Genetics Unit and Marine Genomics Unit of the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, respectively. Y.-H.S. and J.-K.Y. are supported by Academia Sinica and Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. L.P. was supported by NIH grant R01HD073104. The Saccoglossus kowalevskii genome project was supported by a grant from the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health (U54 HG003273) to R.A.G.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.Q., K.C.W. assembled the initial S. kowalevskii genomic assembly and performed quality assessments of the genome assemblies. Ptychodera collection, genome sequencing, and assembly: T.K., K.T., A.S., R.K., H.G., M.F., M.I.K., N.A., S.Y., A.F., T.H. Rhabdopleura collection: A.S. Saccoglossus RNA sequencing and analysis: R.M.F., M.W.K., R.C., C.L.K., S.L.L., M.H., S.R., D.M.M., K.C.W. Genome sequence production: A.C., Y.D., H.H.D., S.D., M.H., S.N.J., C.L.K., S.L.L., L.R.L., D.M., L.V.N., G.O., J.Sa., S.R., K.C.W., D.M.M., L.P., B.F., M.W.K. Saccoglossus sequence finishing: S.D., Y.D., D.M.M. Final Saccoglossus assembly: J.J., J.Sc. Saccoglossus gene modelling and validation: T.M., J.B., J.H.F., A.M.P., M.W. Ptychodera gene modelling and analyses: T.K., R.K., K.H., E.S., F.G., K.W.B., K.T., O.S., J.G., N.S. Gene family analyses: O.S., T.K., F.M., L.P., R.M.F., C.L., J.G. Synteny: N.H.P., O.S., J.-X.Y. Repeats: O.S. Saccoglossus sequencing and assembly project management: S.R., D.M.M., K.C.W., R.A.G. Ptychodera expression analysis: Y.-C.C., Y.-H.S., J.-K.Y. Phylogenetic analyses: F.M. Additional EST collections: T.H.-K., K.T., A.S., A.T.S., J.P., P.G., C.C., C.L. HGT and novelties: J.G., O.S. Pharyngeal cluster analysis and expression: J.G., O.S., N.S., K.B., A.G. Project coordination, manuscript writing: O.S., T.K., F.M., K.T., N.S., J.G., C.L., D.S.R.

Online Content Methods, along with any additional Extended Data display items and Source Data, are available in the online version of the paper; references unique to these sections appear only in the online paper.

Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper.

Author Information Sequencing data have been deposited in NCBI BioProject under accession number PRJNA12887 (Saccoglossus kowalevskii) and DDBJ under accession number PRJDB3182 (Ptychodera flava). Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Bateson W. The later stages in the development of Balanoglossus Kowalevskii, with a suggestion as to the affinities of the Enteropneusta. 2 parts. Q J Microsc Sci. 1885;25:81–122. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bateson W. Memoirs: the ancestry of the Chordata. Q J Microsc Sci. 1886;2:535–572. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovalevskij AO. Anatomie des Balanoglossus delle Chiaje (Mémoires de l’Académie Impériale des Sciences de. St. Pétersbourg: Imperatorskaja Akademija Nauk; 1866. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agassiz A. The history of Balanoglossus and tornaria. Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 1873;9:421–436. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metschnikof V. Über die systematische Stellung von Balanoglossus. Zool Anz. 1881;4:139–157. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halanych KM. The phylogenetic position of the pterobranch hemichordates based on 18S rDNA sequence data. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1995;4:72–76. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1995.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon JT, et al. Phylogenomic resolution of the hemichordate and echinoderm clade. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2827–2832. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogasawara M, Wada H, Peters H, Satoh N. Developmental expression of Pax1/9 genes in urochordate and hemichordate gills: insight into function and evolution of the pharyngeal epithelium. Development. 1999;126:2539–2550. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillis JA, Fritzenwanker JH, Lowe CJ. A stem-deuterostome origin of the vertebrate pharyngeal transcriptional network. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2012;279:237–246. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe CJ, Clarke DN, Medeiros DM, Rokhsar DS, Gerhart J. The deuterostome context of chordate origins. Nature. 2015;520:456–465. doi: 10.1038/nature14434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swalla BJ, Smith AB. Deciphering deuterostome phylogeny: molecular, morphological and palaeontological perspectives. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 2008;363:1557–1568. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron CB, Garey JR, Swalla BJ. Evolution of the chordate body plan: new insights from phylogenetic analyses of deuterostome phyla. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4469–4474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerhart J, Lowe C, Kirschner M. Hemichordates and the origin of chordates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez P, Cameron CB. The gill slits and pre-oral ciliary organ of Protoglossus (Hemichordata: Enteropneusta) are filter-feeding structures. Biol J Linn Soc. 2009;98:898–906. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown FD, Prendergast A, Swalla BJ. Man is but a worm: chordate origins. Genesis. 2008;46:605–613. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holland ND, Holland LZ, Holland PW. Scenarios for the making of vertebrates. Nature. 2015;520:450–455. doi: 10.1038/nature14433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyman LH. The invertebrates: smaller coelomate groups chaetognatha, hemichordata, pogonophora, phoronida, ectoprocta, brachipoda, sipunculida, the coelomate bilateria. Vol. 5. McGraw-Hill; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bourlat SJ, et al. Deuterostome phylogeny reveals monophyletic chordates and the new phylum Xenoturbellida. Nature. 2006;444:85–88. doi: 10.1038/nature05241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Philippe H, et al. Acoelomorph fatworms are deuterostomes related to Xenoturbella. Nature. 2011;470:255–258. doi: 10.1038/nature09676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruiz-Trillo I, Riutort M, Fourcade HM, Baguna J, Boore JL. Mitochondrial genome data support the basal position of Acoelomorpha and the polyphyly of the Platyhelminthes. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;33:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hejnol A, et al. Assessing the root of bilaterian animals with scalable phylogenomic methods. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2009;276:4261–4270. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edgecombe GD, et al. Higher-level metazoan relationships: recent progress and remaining questions. Org Divers Evol. 2011;11:151–172. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srivastava M, Mazza-Curll KL, van Wolfswinkel JC, Reddien PW. Whole-body acoel regeneration is controlled by Wnt and Bmp-Admp signaling. Curr Biol. 2014;24:1107–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lartillot N, Lepage T, Blanquart S. PhyloBayes 3: a Bayesian software package for phylogenetic reconstruction and molecular dating. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2286–2288. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ulitsky I, Shkumatava A, Jan CH, Sive H, Bartel DP. Conserved function of lincRNAs in vertebrate embryonic development despite rapid sequence evolution. Cell. 2011;147:1537–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royo JL, et al. Transphyletic conservation of developmental regulatory state in animal evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14186–14191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109037108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Putnam NH, et al. The amphioxus genome and the evolution of the chordate karyotype. Nature. 2008;453:1064–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature06967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irimia M, et al. Extensive conservation of ancient microsynteny across metazoans due to cis-regulatory constraints. Genome Res. 2012;22:2356–2367. doi: 10.1101/gr.139725.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sodergren E, et al. The genome of the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Science. 2006;314:941–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1133609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freeman R, et al. Identical genomic organization of two hemichordate hox clusters. Curr Biol. 2012;22:2053–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikuta T, et al. Identifcation of an intact ParaHox cluster with temporal colinearity but altered spatial colinearity in the hemichordate Ptychodera fava. BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cameron RA, et al. Unusual gene order and organization of the sea urchin hox cluster. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. 2006;306:45–58. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baughman KW, et al. Genomic organization of Hox and ParaHox clusters in the echinoderm, Acanthaster planci. Genesis. 2014;52:952–958. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santagati F, et al. Identifcation of cis-regulatory elements in the mouse Pax9/Nkx2–9 genomic region: implication for evolutionary conserved synteny. Genetics. 2003;165:235–242. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowe CJ, et al. Dorsoventral patterning in hemichordates: insights into early chordate evolution. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, Zhong J, Su B, Zhou Y, Wang YQ. Comparison of Pax1/9 locus reveals 500-Myr-old syntenic block and evolutionary conserved noncoding regions. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:784–791. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santagati F, et al. Comparative analysis of the genomic organization of Pax9 and its conserved physical association with Nkx2–9 in the human, mouse, and puferfsh genomes. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:232–237. doi: 10.1007/s003350010267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang S, Zhang S, Zhao B, Lun L. Up-regulation of C/EBP by thyroid hormones: a case demonstrating the vertebrate-like thyroid hormone signaling pathway in amphioxus. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;313:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowe CJ, et al. Anteroposterior patterning in hemichordates and the origins of the chordate nervous system. Cell. 2003;113:853–865. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00469-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kokubu C, et al. A transposon-based chromosomal engineering method to survey a large cis-regulatory landscape in mice. Nature Genet. 2009;41:946–952. doi: 10.1038/ng.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giacopuzzi E, Bresciani R, Schauer R, Monti E, Borsani G. New insights on the sialidase protein family revealed by a phylogenetic analysis in metazoa. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harduin-Lepers A, Mollicone R, Delannoy P, Oriol R. The animal sialyltransferases and sialyltransferase-related genes: a phylogenetic approach. Glycobiology. 2005;15:805–817. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwi063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harduin-Lepers A, et al. Evolutionary history of the alpha2,8-sialyltransferase (ST8Sia) gene family: tandem duplications in early deuterostomes explain most of the diversity found in the vertebrate ST8Sia genes. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:258. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pardos F. Fine structure and function of pharynx cilia in Glossobalanus minutus Kowalewsky (Enteropneusta) Acta Zoologica. 1988;69:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaul-Strehlow S, Stach T. A detailed description of the development of the hemichordate Saccoglossus kowalevskii using SEM, TEM, Histology and 3D-reconstructions. Front Zool. 2013;10:53. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-10-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruppert EE, Cameron CB, Frick JE. Endostyle-like features of the dorsal epibranchial ridge of an enteropneust and the hypothesis of dorsal-ventral axis inversion in chordates. Invertebr Biol. 1999;118:202–212. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Range R, Lepage T. Maternal Oct1/2 is required for Nodal and Vg1/Univin expression during dorsal-ventral axis specifcation in the sea urchin embryo. Dev Biol. 2011;357:440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Massagué J. TGFβ signalling in context. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:616–630. doi: 10.1038/nrm3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Range R, et al. Cis-regulatory analysis of nodal and maternal control of dorsal-ventral axis formation by Univin, a TGF-β related to Vg1. Development. 2007;134:3649–3664. doi: 10.1242/dev.007799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jafe DB, et al. Whole-genome sequence assembly for mammalian genomes: Arachne 2. Genome Res. 2003;13:91–96. doi: 10.1101/gr.828403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kajitani R, et al. Efficient de novo assembly of highly heterozygous genomes from whole-genome shotgun short reads. Genome Res. 2014;24:1384–1395. doi: 10.1101/gr.170720.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romiguier J, et al. Comparative population genomics in animals uncovers the determinants of genetic diversity. Nature. 2014;515:261–263. doi: 10.1038/nature13685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tagawa K, et al. A cDNA resource for gene expression studies of a hemichordate, Ptychodera fava. Zoolog Sci. 2014;31:414–420. doi: 10.2108/zs130262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen SH, et al. Sequencing and analysis of the transcriptome of the acorn worm Ptychodera fava, an indirect developing hemichordate. Mar Genomics. 2014;15:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.margen.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salamov AA, Solovyev VV. Ab initio gene fnding in Drosophila genomic DNA. Genome Res. 2000;10:516–522. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.4.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stanke M, Waack S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(Suppl. 2):ii215–ii225. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simakov O, et al. Insights into bilaterian evolution from three spiralian genomes. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature11696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identifcation of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl. 1):i351–i358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jurka J, et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smit A, Hubley R, Green P. RepeatMasker. 2007 http://www.repeatmasker.org.

- 61.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldon T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aberer A, Stamatakis A. ExaML: Exascale maximum likelihood: program and documentation. 2013 See http://sco.h-its.org/exelixis/web/software/examl/index.html.

- 64.Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee AP, Kerk SY, Tan YY, Brenner S, Venkatesh B. Ancient vertebrate conserved noncoding elements have been evolving rapidly in teleost fshes. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:1205–1215. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cunningham F, et al. Ensembl 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D662–D669. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Visel A, Minovitsky S, Dubchak I, Pennacchio LA. VISTA Enhancer Browser–a database of tissue-specifc human enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D88–D92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marchler-Bauer A, et al. CDD: NCBI’s conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D222–D226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marinić M, Aktas T, Ruf S, Spitz F. An integrated holo-enhancer unit defnes tissue and gene specifcity of the Fgf8 regulatory landscape. Dev Cell. 2013;24:530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Information

data

data1

data2