Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance in Microbial Ecosystems through Horizontal Gene Transfer (original) (raw)

Abstract

The emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance among pathogenic bacteria has been a rising problem for public health in recent decades. It is becoming increasingly recognized that not only antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) encountered in clinical pathogens are of relevance, but rather, all pathogenic, commensal as well as environmental bacteria—and also mobile genetic elements and bacteriophages—form a reservoir of ARGs (the resistome) from which pathogenic bacteria can acquire resistance via horizontal gene transfer (HGT). HGT has caused antibiotic resistance to spread from commensal and environmental species to pathogenic ones, as has been shown for some clinically important ARGs. Of the three canonical mechanisms of HGT, conjugation is thought to have the greatest influence on the dissemination of ARGs. While transformation and transduction are deemed less important, recent discoveries suggest their role may be larger than previously thought. Understanding the extent of the resistome and how its mobilization to pathogenic bacteria takes place is essential for efforts to control the dissemination of these genes. Here, we will discuss the concept of the resistome, provide examples of HGT of clinically relevant ARGs and present an overview of the current knowledge of the contributions the various HGT mechanisms make to the spread of antibiotic resistance.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, resistome, transformation, conjugation, transduction, gene transfer agents, GTA, lateral gene transfer

Introduction

The ever-increasing magnitude of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) encountered in human pathogens is a huge concern for public health worldwide, limiting treatment options for bacterial infections and thereby reducing clinical efficacy while increasing treatment costs and mortality. With a lack of development of new antibiotics, and increasing resistance even to last-resort antibiotics (Nordmann et al., 2012), there is a need to conserve the ones available.

Natural antibiotics have existed for billions of years (Barlow and Hall, 2002; Hall and Barlow, 2004; Bhullar et al., 2012; Wright and Poinar, 2012), providing a selective benefit for the producing strains by inhibiting or eliminating other bacteria competing for resources (Martinez, 2008; Aminov, 2009). Additionally, their function as cell-cell signaling molecules has been described (Davies, 2006; Linares et al., 2006). Just as antibiotics are ancient, so are antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), as evidenced by studies identifying various ARGs in ancient permafrost samples (D'Costa et al., 2011; Perron et al., 2015) and isolated cave microbiomes (Bhullar et al., 2012). Resistance to antibiotics can occur either by mutations or by acquisition of resistance conferring genes via horizontal gene transfer (HGT), of which the latter is considered to be the most important factor in the current pandemic of AMR.

The HGT of ARGs also far predates the production and use of antibiotics by humans. For example, OXA-type β-lactamases were found to be plasmid-borne and able to transfer between bacterial species millions of years ago (Barlow and Hall, 2002). However, while antibiotic resistance and its spread by HGT are ancient mechanisms, the rate at which these processes occur and the number of resistant strains has increased tremendously over the past few decades because of selective pressure through human antibiotic use.

The global antibiotic selection pressure

While the discovery of antibiotics revolutionized the field of medicine, their increasingly large-scale production and consumption has had widespread effects on the microbial biosphere. In their analysis, Van Boeckel et al. showed that global human antibiotic consumption amounted to 54,083,964,813 standard units (pills, capsules, or ampoules) in 2000 and had increased by 36% to 73,620,748,816 standard units by 2010 (Van Boeckel et al., 2014). The same authors estimated that antibiotic consumption in food animals, which is assumed to be larger than that of humans, was over 63 million kg in 2010 and will also drastically increase in the coming years (Van Boeckel et al., 2015) despite recent initiatives to reduce antibiotic use in animals. Such high and continuously increasing amounts of antibiotics overwhelm the natural production, causing a constantly increasing selection pressure on bacterial populations in all exposed environments.

The use and misuse of antibiotics in medicine, agriculture, and aquaculture has been linked to the emergence of resistant bacteria in these settings (Cabello, 2006; Penders and Stobberingh, 2008; Economou and Gousia, 2015). However, the impact of antibiotic usage extends further, as antibiotic residues, resistant bacteria, and genetic resistance elements subsequently spread to adjacent environments. The majority of consumed antibiotics are excreted unchanged (Sarmah et al., 2006) and are then introduced into the environment directly or through waste streams. Such waste streams, as well as wastewater treatment plants, are considered to be hotspots for the dissemination of AMR, since resistance genes, mobile genetic elements (MGEs), and (sub-inhibitory) antibiotic selection pressure from various sources are introduced to commensals and pathogens (Tennstedt et al., 2003; Martinez, 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Graham et al., 2011). Moreover, the antibiotic compounds are often not completely removed in treatment plants (Watkinson et al., 2007; Le-Minh et al., 2010), from where they then disseminate further. A study by Larsson et al. showed that a treatment plant in India, receiving water from drug manufacturing sites, exposes its direct environment to very high levels of antibiotics, discharging ~45 kg of ciprofloxacin per day (Larsson et al., 2007), contaminating surface, ground, and drinking water in the area (Fick et al., 2009). As a result, not only were highly multiresistant bacteria found to be common within the treatment plant (Marathe et al., 2013), but high levels of ARGs and MGEs were also detected in nearby river sediments (Kristiansson et al., 2011).

How environmental exposure to antibiotics contributes to the selection of resistant strains and the increase of resistome elements is illustrated by a study comparing soil samples taken between 1940 and 2008, which shows that ARGs from all classes of antibiotics tested (β-lactams, tetracyclines, erythromycins, and glycopeptides) significantly increased since 1940, with a tetracycline ARG being over 15 times more abundant than in the 1970s (Knapp et al., 2010). Moreover, the increasing selection pressure has altered bacterial HGT processes, increasing the number of resistome elements which reside on mobile DNA compared to the pre-antibiotic era (Datta and Hughes, 1983).

Reservoirs of resistance

In order to understand the dissemination of antibiotic resistance, it is necessary to map the resistome of various environments, and to unravel to what extend these environments can act as a reservoir for the dissemination of ARGs to bacterial pathogens. In recent years there has been increasing interest in this matter, as many studies have used various techniques to sample the resistome of environments such as, but not limited to, soil, wastewater, and human and animal gut microbiota (Pehrsson et al., 2013; Penders et al., 2013; Rizzo et al., 2013; von Wintersdorff et al., 2014). It has since become clear that ARGs, including clinically relevant ones, are widespread in such environments (Wright, 2010). Studies applying a metagenomic approach directly recover DNA from all micro-organisms in a biological sample, thereby avoiding the bias that is introduced when selecting certain organisms, and allowing for the investigation of the resistome of microbial ecosystems. The sequencing of metagenomes from various environments has led to a wealth of data which is often publicly available in databases. Such databases can be mined for the presence of resistance genes, even when the initial studies did not focus specifically on ARG content in these metagenomes. For example, mining such metagenomic databases for the plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-1, which has recently been discovered in clinical and commensal isolates (Arcilla et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015), has revealed that this gene had already spread to the human gut microbiome of Chinese subjects several years ago (Hu et al., 2015). While sequence based studies provide huge amounts of data, they are limited to either identifying genes that are already known, or to predicting novel sequence functions based on high homology to known sequences. Annotation by sequence-based studies will keep increasing however, as studies using functional metagenomics keep identifying novel ARGs. An increasing number of such studies have revealed a huge number of previously unknown ARGs present in environments such as soil (Riesenfeld et al., 2004; D'Costa et al., 2006; Allen et al., 2009; Donato et al., 2010; Torres-Cortes et al., 2011; Perron et al., 2015) or activated sludge (Mori et al., 2008; Parsley et al., 2010), as well as in the microbiota of animals (Kazimierczak et al., 2009; Wichmann et al., 2014) and humans (Sommer et al., 2009; Cheng et al., 2012; Moore et al., 2013, 2015; Card et al., 2014; Fouhy et al., 2014; Clemente et al., 2015).

Recent metagenomic studies have also uncovered that ARGs predominantly cluster by ecology, implying that the resistome in soils, and wastewater treatment plants differ significantly from that of human pathogens (Gibson et al., 2015; Munck et al., 2015). Nonetheless, the authors of these works note that parts of these resistomes are shared (Forsberg et al., 2012) and stress the importance of continuing the exploration of the resistome of such environments.

That commensals and the environment are important reservoirs for resistance is supported by several examples of ARGs on MGEs in human pathogens that appear to have originated from those reservoirs. A well-known example is that of the _bla_CTX−M genes, which have become the most prevalent cause of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in Enterobacteriaceae worldwide and a major cause of clinical treatment problems (Hawkey and Jones, 2009). The potential origin of these genes was identified as the chromosomal DNA of various environmental Kluyvera species, from where they spread very successfully to different bacterial species (Canton and Coque, 2006). Shewanella algae, a marine and freshwater species, was found to be the origin of plasmid-encoded qnrA genes, conferring quinolone resistance (Poirel et al., 2005a), and different Vibrionaceae species might be the reservoir for other plasmid-encoded qnr genes (Poirel et al., 2005b), which have disseminated globally in various Enterobacteriaceae species, with exceptionally high prevalence rates in some areas (Vien le et al., 2012). The OXA-48-type carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase genes, which are increasingly reported in enterobacterial species worldwide, were also found to originate from the chromosomes of waterborne, environmental Shewanella species (Poirel et al., 2012). As with these few examples, many clinically relevant resistance genes are believed to have originated from non-pathogenic bacteria, highlighting the immense potential of HGT for these pathogens in overcoming human use of antibiotics.

Contribution of the various HGT mechanisms to the spread of ARGs

Conjugation

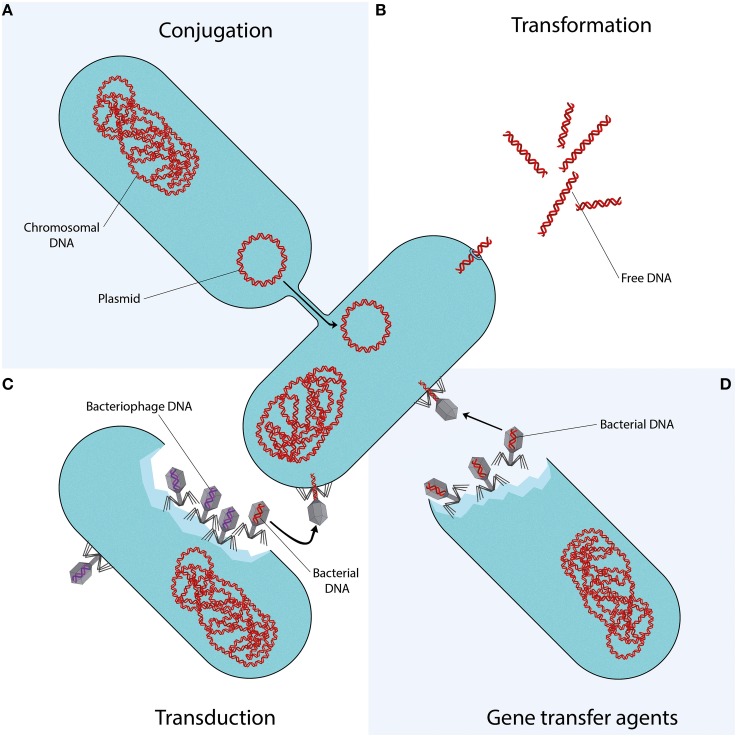

Conjugation is the transfer of DNA through a multi-step process requiring cell to cell contact via cell surface pili or adhesins. It is facilitated by the conjugative machinery which is encoded either by genes on autonomously replicating plasmids or by integrative conjugative elements in the chromosome (Smillie et al., 2010; Wozniak and Waldor, 2010). Additionally, this conjugative machinery may enable the mobilization of plasmids that are non-conjugative, as observed for e.g., the exceptionally broad host range IncQ plasmids (Meyer, 2009). Of the various mechanisms that may facilitate HGT (Figure 1), conjugation is certainly the most commonly studied (Norman et al., 2009; Guglielmini et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of horizontal gene transfer. Each quadrant represents one different method of gene transfer. (A) Conjugation is a process requiring cell to cell contact via cell surface pili or adhesins, through which DNA is transferred from the donor cell to the recipient cell. (B) Transformation is the uptake, integration, and functional expression of naked fragments of extracellular DNA. (C) Through specialized or generalized transduction, bacteriophages may transfer bacterial DNA from a previously infected donor cell to the recipient cell. During generalized transduction, bacterial DNA may be accidentally loaded into the phage head (shown as a phage with a red DNA strand). During specialized transduction, genomic DNA neighboring the prophage DNA is co-excised and loaded into a new phage (not shown). (D) Gene transfer agents (GTAs) are bacteriophage-like particles that carry random pieces of the producing cell's genome. GTA particles may be released through cell lysis and spread to a recipient cell.

ARGs are in many cases associated with conjugative elements such as plasmids or transposons. While the transfer of these elements may also occur through transformation or transduction, conjugation is often considered as the most likely responsible mechanism. This is due to the fact that it provides better protection from the surrounding environment and a more efficient means of entering the host cell than transformation, while often having a broader host range than bacteriophage transduction. Moreover, while conjugation is a process directed toward the transfer of bacterial genes, transfer of bacterial DNA by transduction is a side-effect of erroneous bacteriophage replication (Norman et al., 2009).

The conjugation of MGEs conferring AMR has been observed in many types of ecosystems, ranging from transfer between bacteria in insects, soil, and water environments to various food and healthcare associated pathogens (Davison, 1999). Importantly, transfer of plasmids and conjugative transposons, such as those of the Tn916 family, between unrelated bacteria over large taxonomic distances has been described (Shoemaker et al., 2001; Musovic et al., 2006; Roberts and Mullany, 2009; Tamminen et al., 2012), indicating that this mechanism contributes significantly to the dissemination of ARGs between different reservoirs via such broad host range MGEs.

The spread of antibiotic resistance plasmids in human pathogens is especially well studied, and shows that once resistance genes have become established on successful plasmids, they may rapidly spread across different strains, species, or even genera. This is well demonstrated by the _bla_CTX−M ESBL genes, which have disseminated to various narrow and broad host range plasmids within Enterobacteriaceae, as well as to other opportunistic human pathogens (Canton et al., 2012). These genes are now ubiquitous in humans (Woerther et al., 2013), animals, and the environment (Hartmann et al., 2012). Furthermore, the transfer of plasmids in pathogens has led to the worldwide spread of numerous ARGs encoding resistance to β-lactams, quinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and many other drug classes (Huddleston, 2014). Of particular concern is the increasingly reported spread of plasmids harboring carbapenem resistance (Carattoli, 2013) and the recent discovery of plasmid-encoded colistin resistance in China (Liu et al., 2015), which has now already been identified at multiple continents (Arcilla et al., 2015) and may cause Enterobacteriaceae to truly become pan-drug resistant. Moreover, multiple ARGs are often co-localized on the same plasmid, which allows for the relatively easy spread of multidrug resistance.

Transformation

In 1928, Griffith became the first to demonstrate direct genetic exchange between different strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae (Griffith, 1928). Certain bacteria appeared to be capable of uptake, integration, and functional expression of naked fragments of extracellular DNA, a process called (natural) transformation. It soon became clear that bacteria could use transformation to evade antibiotics, by exchanging ARGs. In 1951, Hotchkiss induced penicillin and streptomycin resistance in previously sensitive strains of S. pneumoniae by exposing them to DNA from resistant strains (Hotchkiss, 1951). Alexander et al. furthered this work by demonstrating intra- and inter-species transfer of streptomycin resistance between H. influenzae, H. parainfluenzae, and H. suis (Alexander and Leidy, 1953; Alexander et al., 1956).

In order for transformation to take place, several conditions have to be met. There must be DNA present in the extracellular environment; the recipient bacteria must be in a state of competence; and the translocated DNA must be stabilized, either by integration into the recipient genome, or by recircularisation (in the case of plasmid DNA) (Thomas and Nielsen, 2005). Whereas Neisseria spp. are considered to be constitutively competent (Sparling, 1966; Johnston et al., 2014), other bacterial species capable of natural transformation may develop competence only under certain conditions, such as the presence of peptides or autoinducers, nutritional status, or other stressful conditions, as reviewed in more detail by Johnston et al. (2014). Importantly, studies have shown that exposure to antibiotics can induce competence in many species of bacteria, meaning that antibiotics would not only select for resistant strains, but also stimulate transformation of their ARGs (Prudhomme et al., 2006; Charpentier et al., 2011, 2012).

In vitro experiments have done much to elucidate transformation of ARGs. Early work proved that ARGs could be transformed; to this end, streptomycin, rifampicin, erythromycin, nalidixic acid, and kanamycin resistance have variously been transformed into Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Sparling, 1966), Bacillus spp. (Harford and Mergeay, 1973), Gallibacterium anatis (Kristensen et al., 2012), and S. pneumoniae (Prudhomme et al., 2006). The introduction of molecular techniques allowed for the identification of the ARGs being transformed. In vitro studies have shown that the genes parC and gyrA are involved in the transformation of fluoroquinolone resistance between S. pneumoniae (Ferrandiz et al., 2000) and several viridans streptococci (Gonzalez et al., 1998; Janoir et al., 1999), and that transformation of penA confers penicillin resistance in commensal Neisseria species (N. flavescens and N. cinerea) and N. meningitidis (Bowler et al., 1994).

Molecular techniques have also made it possible to look for evidence of transformation outside of the laboratory. Spratt et al. identified the penA variant responsible for penicillin resistance in clinical isolates of N. gonorrhoeae (Spratt, 1988); sequence analysis revealed a mosaic structure, with blocks homologous to susceptible-type penA and blocks that diverge significantly (Spratt et al., 1992). These “resistant blocks” could be traced back to a strain of N. flavescens that had been isolated in the pre-antibiotic era, suggesting that such commensal species could have been the original source for the now ubiquitous resistance to penicillin (Spratt et al., 1989; Lujan et al., 1991). Mosaic genes are formed when sections of foreign DNA are incorporated into a recipient genome, as is the case in transformation. Their presence implies that HGT has taken place (Hakenbeck, 1998). In streptococci, the mosaic penicillin-binding protein (PBP) genes that encode PBPs with decreased affinity for β-lactam antibiotics are believed to be the result of gene transfer from related penicillin-resistant species (Sibold et al., 1994) and have disseminated penicillin resistance between various streptococci species (Dowson et al., 1990). Studies of fluoroquinolone resistance have demonstrated that mosaic variants of the genes parC, parE, and gyrA are readily transformed between S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus oralis (Balsalobre et al., 2003), and between Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus dysgalactiae (Pletz et al., 2006).

Mao et al. developed a technique to extract intra- and extracellular DNA separately from environmental samples, and applied it to samples from a river basin in China. The result—a greater abundance of DNA outside of cells than inside—implies that in certain environments, extracellular DNA is a large reservoir for genes which may be accessible via transformation (Mao et al., 2014). Furthermore, Domingues et al. demonstrated that MGEs such as transposons, integrons and gene cassettes can be disseminated efficiently between species, regardless of their level of genetic relatedness (Domingues et al., 2012). Similarly, streptococcal species have been shown to exchange conjugative transposons via transformation in addition to conjugation (Chancey et al., 2015). All of this indicates that transformation provides a broad capacity for the horizontal spread of resistance elements between divergent species.

Transduction

Bacteriophages play an important role in shaping the bacterial microbiome in any environment. Through specialized or generalized transduction, bacteriophages can transfer genes that are advantageous to their microbial hosts, in turn promoting their own survival and dissemination (Modi et al., 2013). The transferable DNA sequences range from chromosomal DNA to MGEs such as plasmids, transposons and genomic islands (Brown-Jaque et al., 2015).

The mobilization or transfer of ARGs by bacteriophages has been documented for various bacterial species: the transduction of erythromycin (Hyder and Streitfeld, 1978), tetracycline or multiple resistances between strains of S. pyogenes (Ubukata et al., 1975); the transfer of tetracycline and gentamicin resistance between enterococci (Mazaheri Nezhad Fard et al., 2011); the carriage of β-lactamase genes by bacteriophages in Escherichia coli (Billard-Pomares et al., 2014) and Salmonella (Schmieger and Schicklmaier, 1999); or the transfer of antibiotic resistance plasmids in MRSA (Varga et al., 2012).

Recent studies applying metagenomic approaches to samples from various environments have suggested that bacteriophages may play a bigger part in the spread of ARGs than previously recognized. Colomer-Lluch et al. used qPCR to show that the β-lactam ARGs _bla_TEM, _bla_CTX−M and mecA were present in bacteriophages from river and urban sewage water samples. Additionally, cloning of the phage DNA into ampicillin susceptible E. coli hosts resulted in resistant transformants, harboring either the _bla_TEM, _bla_CTX−M, or undetermined ARGs (Colomer-Lluch et al., 2011a). In another study, the presence of ARGs in bacteriophages was detected in respiratory tract DNA of cystic fibrosis patients (Rolain et al., 2011). Modi et al. demonstrated that treatment with antibiotics increased the number of ARGs in the intestinal phageome of mice and expanded the interactions between phage and bacterial species (Modi et al., 2013), which is an important observation considering the increased environmental exposure to antibiotics discussed earlier. Furthermore, several studies have used qPCR to detect ARGs in bacteriophages from wastewater samples (Colomer-Lluch et al., 2014a,b), animal and human fecal samples (Colomer-Lluch et al., 2011b; Quiros et al., 2014), wastewater and sludge derived from wastewater treatment plants (Calero-Caceres et al., 2014), and hospital and wastewater treatment plant effluents (Marti et al., 2014), indicating that bacteriophages are significant reservoirs of ARGs. Shousha et al. investigated bacteriophages isolated from chicken meat and found that about a quarter of the randomly isolated bacteriophages were able to transduce resistance to one or more antibiotics into an E. coli host. Moreover, they found a significant relationship between the presence of bacteriophages transducing kanamycin ARGs, and E. coli isolates resistant to kanamycin, implying a possible role of this mechanism in the spread of AMR (Shousha et al., 2015).

Considering certain bacteriophages have been reported to have a wide host range that crosses between different species (Mazaheri Nezhad Fard et al., 2011) or even different taxonomic classes (Jensen et al., 1998), the observation of the plethora of ARGs carried by bacteriophages in various bacterial communities and environments provides renewed insights into the role of transduction in the dissemination of ARGs in microbial ecosystems.

Gene transfer agents

Gene transfer agents (GTAs), first identified in Rhodobacter capsulatus (RcGTA) in 1974 (Marrs, 1974), are host-cell produced particles that resemble bacteriophage structures, capable of transferring genetic content. GTAs have several characteristic features: (i) rather than carrying DNA encoding their own machinery (as with self-propagating bacteriophages), GTAs carry random pieces of the producing cell's genome (Marrs, 1974; Humphrey et al., 1997; Stanton, 2007; Hynes et al., 2012); (ii) the amount of DNA packaged by the GTAs is insufficient to encode all of their protein components, making them unable to self-propagate (Lang and Beatty, 2000, 2001, 2007); (iii) GTA production is controlled by cell regulatory mechanisms (Lang and Beatty, 2000; Leung et al., 2012; Mercer et al., 2012; Brimacombe et al., 2014); (iv) GTA particles are released through cell lysis (Hynes et al., 2012; Westbye et al., 2013) although cultures do not display observable lysis (Marrs, 1974) as only a small subpopulation of GTA-producing cultures (~3%) is responsible for ~95% of GTA release (Fogg et al., 2012; Hynes et al., 2012); (v) recently, it has been proposed that GTAs combine key aspects of transduction and transformation for cell entry, requiring proteins involved in natural transformation (Brimacombe et al., 2015).

Although GTA particles do not necessarily carry any GTA-encoding genes (Lang et al., 2012), RcGTA-like gene clusters are widespread in alphaproteobacteria, especially in the Rhodobacterales: a complete set of RcGTA-like structural genes has been demonstrated in nearly every sequenced member of the Rhodobacterales (Lang and Beatty, 2007; Lang et al., 2012). Moreover, two species in the order of Rhodobacterales, Roseovarius nubinhibens and Ruegeria mobilis, are known to produce GTAs, and there is evidence of GTA production in Ruegeria pomeroyi (Biers et al., 2008; McDaniel et al., 2010; Lang et al., 2012). Other known GTAs are VSH-1 in the spirochaete Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, Dd1 in the deltaproteobacterium Desulfovibrio desulfuricans, and VTA in the archaeon Methanococcus voltae (Lang and Beatty, 2007; Lang et al., 2012). The genes required for GTA-production are contained within the host genome and appear to have been propagated through vertical transmission (Lang and Beatty, 2007).

It has been suggested that GTAs have several advantages over the previously described mechanisms of HGT (Stanton, 2007): GTA particles afford DNA protection from damaging environmental factors, as opposed to the naked DNA involved in natural transformation; compared to conjugation, the transfer ability of GTAs is likely maintained after conditions killing the host cell, and is moreover not constrained by cell-to-cell contact; lastly, compared to transduction, GTA particles predominantly carry random pieces of host genome, rather than mostly bacteriophage DNA. In the marine environment, GTA-mediated transfer events have been reported to be remarkably high; up to several million times higher than previous estimates of HGT in marine environments, exceeding previously described transformation and transduction frequencies (McDaniel et al., 2010). Moreover, genes can be exchanged between bacterial phyla (McDaniel et al., 2010; Lang et al., 2012), suggesting the possible widespread contribution of GTAs in shaping and driving adaptation of the natural environment.

In culture, GTA mediated transfer of antibiotic resistance markers has been readily demonstrated in R. capsulatus (Marrs, 1974; Solioz et al., 1975; Wall et al., 1975) and the spirochaete Brachyspira hyodesenteriae (Stanton et al., 2001, 2008). Moreover, GTAs have been used to transfer traits from plasmids (Scolnik and Haselkorn, 1984). In addition, the B. hyodesenteriae GTA VSH-1 can be induced by certain antibiotics (Stanton et al., 2008), which points out its possible impact in its natural environment, the swine intestinal tract. Other Brachyspira spp. occur in the intestinal tract of other species, including humans and chickens (Hampson and Ahmed, 2009), in which VSH-1 genes have been described (Motro et al., 2009). However, interspecies GTA-mediated transfer remains to be demonstrated (Motro et al., 2009).

The impact of GTAs on human health has yet to be established, but given the high frequency of transfer events in certain environments, and their ability to exchange genes between phyla, their potential to act as vehicles of resistance traits in the environment, and within the microbiota of humans and farmed animals is an area worthy of further study.

Conclusion

The increase in environmental levels of antibiotics, driven by medical and agricultural demand, is unprecedented and has disrupted the natural balance between microbes and antimicrobials. The effects this has on microbial communities are wide-ranging, and the result is an increasingly tangible threat to healthcare, as resistance to all known antibiotics disseminates rapidly around the globe. Our knowledge of the interactions between antimicrobials and resistance against it, observed not only in the clinic but across different ecosystems around the world, is rapidly increasing and has provided valuable insights. However, it is vital that we continue to unravel the extent of, and dissemination between resistomes of these microbial ecosystems, as any attempt at coming to terms with the AMR problem will have to account for these vast reservoirs of ARGs.

Author contributions

CW, JN, SM wrote the article. CW, JN made the Figure. JP, LA, PS, PW provided feedback and discussion on the article.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander H. E., Hahn E., Leidy G. (1956). On the specificity of the desoxyribonucleic acid which induces streptomycin resistance in Hemophilus. J. Exp. Med. 104, 305–320. 10.1084/jem.104.3.305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander H. E., Leidy G. (1953). Induction of streptomycin resistance in sensitive Hemophilus influenzae by extracts containing desoxyribonucleic acid from resistant Hemophilus influenzae. J. Exp. Med. 97, 17–31. 10.1084/jem.97.1.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen H. K., Moe L. A., Rodbumrer J., Gaarder A., Handelsman J. (2009). Functional metagenomics reveals diverse β-lactamases in a remote Alaskan soil. ISME J. 3, 243–251. 10.1038/ismej.2008.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminov R. I. (2009). The role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2970–2988. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01972.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcilla M. S., van Hattem J. M., Matamoros S., Melles D. C., Penders J., de Jong M. D., et al. (2015). Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 147–149. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00541-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsalobre L., Ferrandiz M. J., Linares J., Tubau F., de la Campa A. G. (2003). Viridans group streptococci are donors in horizontal transfer of topoisomerase IV genes to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 2072–2081. 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2072-2081.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow M., Hall B. G. (2002). Phylogenetic analysis shows that the OXA β-lactamase genes have been on plasmids for millions of years. J. Mol. Evol. 55, 314–321. 10.1007/s00239-002-2328-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhullar K., Waglechner N., Pawlowski A., Koteva K., Banks E. D., Johnston M. D., et al. (2012). Antibiotic resistance is prevalent in an isolated cave microbiome. PLoS ONE 7:e34953. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biers E. J., Wang K., Pennington C., Belas R., Chen F., Moran M. A. (2008). Occurrence and expression of gene transfer agent genes in marine bacterioplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2933–2939. 10.1128/AEM.02129-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billard-Pomares T., Fouteau S., Jacquet M. E., Roche D., Barbe V., Castellanos M., et al. (2014). Characterization of a P1-like bacteriophage carrying an SHV-2 extended-spectrum β-lactamase from an Escherichia coli strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 6550–6557. 10.1128/AAC.03183-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler L. D., Zhang Q. Y., Riou J. Y., Spratt B. G. (1994). Interspecies recombination between the penA genes of Neisseria meningitidis and commensal Neisseria species during the emergence of penicillin resistance in N. meningitidis: natural events and laboratory simulation. J. Bacteriol. 176, 333–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimacombe C. A., Ding H., Beatty J. T. (2014). Rhodobacter capsulatus DprA is essential for RecA-mediated gene transfer agent (RcGTA) recipient capability regulated by quorum-sensing and the CtrA response regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 92, 1260–1278. 10.1111/mmi.12628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimacombe C. A., Ding H., Johnson J. A., Beatty J. T. (2015). Homologues of genetic transformation DNA import genes are required for Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent recipient capability regulated by the response regulator CtrA. J. Bacteriol. 197, 2653–2663. 10.1128/JB.00332-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Jaque M., Calero-Caceres W., Muniesa M. (2015). Transfer of antibiotic-resistance genes via phage-related mobile elements. Plasmid 79, 1–7. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello F. C. (2006). Heavy use of prophylactic antibiotics in aquaculture: a growing problem for human and animal health and for the environment. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 1137–1144. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calero-Caceres W., Melgarejo A., Colomer-Lluch M., Stoll C., Lucena F., Jofre J., et al. (2014). Sludge as a potential important source of antibiotic resistance genes in both the bacterial and bacteriophage fractions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 7602–7611. 10.1021/es501851s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton R., Coque T. M. (2006). The CTX-M β-lactamase pandemic. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 466–475. 10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canton R., Gonzalez-Alba J. M., Galan J. C. (2012). CTX-M enzymes: origin and diffusion. Front. Microbiol. 3:110. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A. (2013). Plasmids and the spread of resistance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 303, 298–304. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card R. M., Warburton P. J., MacLaren N., Mullany P., Allan E., Anjum M. F. (2014). Application of microarray and functional-based screening methods for the detection of antimicrobial resistance genes in the microbiomes of healthy humans. PLoS ONE 9:e86428. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chancey S. T., Agrawal S., Schroeder M. R., Farley M. M., Tettelin H., Stephens D. S. (2015). Composite mobile genetic elements disseminating macrolide resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 6:26. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier X., Kay E., Schneider D., Shuman H. A. (2011). Antibiotics and UV radiation induce competence for natural transformation in Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 193, 1114–1121. 10.1128/JB.01146-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier X., Polard P., Claverys J. P. (2012). Induction of competence for genetic transformation by antibiotics: convergent evolution of stress responses in distant bacterial species lacking SOS? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15, 570–576. 10.1016/j.mib.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G., Hu Y., Yin Y., Yang X., Xiang C., Wang B., et al. (2012). Functional screening of antibiotic resistance genes from human gut microbiota reveals a novel gene fusion. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 336, 11–16. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02647.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente J. C., Pehrsson E. C., Blaser M. J., Sandhu K., Gao Z., Wang B., et al. (2015). The microbiome of uncontacted Amerindians. Sci. Adv. 1:e1500183. 10.1126/sciadv.1500183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer-Lluch M., Calero-Caceres W., Jebri S., Hmaied F., Muniesa M., Jofre J. (2014a). Antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial and bacteriophage fractions of Tunisian and Spanish wastewaters as markers to compare the antibiotic resistance patterns in each population. Environ. Int. 73, 167–175. 10.1016/j.envint.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer-Lluch M., Imamovic L., Jofre J., Muniesa M. (2011b). Bacteriophages carrying antibiotic resistance genes in fecal waste from cattle, pigs, and poultry. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 4908–4911. 10.1128/AAC.00535-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer-Lluch M., Jofre J., Muniesa M. (2011a). Antibiotic resistance genes in the bacteriophage DNA fraction of environmental samples. PLoS ONE 6:e17549. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer-Lluch M., Jofre J., Muniesa M. (2014b). Quinolone resistance genes (qnrA and qnrS) in bacteriophage particles from wastewater samples and the effect of inducing agents on packaged antibiotic resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 1265–1274. 10.1093/jac/dkt528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta N., Hughes V. M. (1983). Plasmids of the same Inc groups in Enterobacteria before and after the medical use of antibiotics. Nature. 306, 616–617. 10.1038/306616a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J. (2006). Are antibiotics naturally antibiotics? J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33, 496–499. 10.1007/s10295-006-0112-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison J. (1999). Genetic exchange between bacteria in the environment. Plasmid 42, 73–91. 10.1006/plas.1999.1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Costa V. M., King C. E., Kalan L., Morar M., Sung W. W., Schwarz C., et al. (2011). Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature 477, 457–461. 10.1038/nature10388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Costa V. M., McGrann K. M., Hughes D. W., Wright G. D. (2006). Sampling the antibiotic resistome. Science 311, 374–377. 10.1126/science.1120800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingues S., Harms K., Fricke W. F., Johnsen P. J., da Silva G. J., Nielsen K. M. (2012). Natural transformation facilitates transfer of transposons, integrons and gene cassettes between bacterial species. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002837. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato J. J., Moe L. A., Converse B. J., Smart K. D., Berklein F. C., McManus P. S., et al. (2010). Metagenomic analysis of apple orchard soil reveals antibiotic resistance genes encoding predicted bifunctional proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 4396–4401. 10.1128/AEM.01763-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowson C. G., Hutchison A., Woodford N., Johnson A. P., George R. C., Spratt B. G. (1990). Penicillin-resistant viridans streptococci have obtained altered penicillin-binding protein genes from penicillin-resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 5858–5862. 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economou V., Gousia P. (2015). Agriculture and food animals as a source of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. Infect. Drug Resist. 8, 49–61. 10.2147/IDR.S55778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandiz M. J., Fenoll A., Linares J., De La Campa A. G. (2000). Horizontal transfer of parC and gyrA in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 840–847. 10.1128/AAC.44.4.840-847.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick J., Soderstrom H., Lindberg R. H., Phan C., Tysklind M., Larsson D. G. (2009). Contamination of surface, ground, and drinking water from pharmaceutical production. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 28, 2522–2527. 10.1897/09-073.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogg P. C., Westbye A. B., Beatty J. T. (2012). One for all or all for one: heterogeneous expression and host cell lysis are key to gene transfer agent activity in Rhodobacter capsulatus. PLoS ONE 7:e43772. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg K. J., Reyes A., Wang B., Selleck E. M., Sommer M. O., Dantas G. (2012). The shared antibiotic resistome of soil bacteria and human pathogens. Science 337, 1107–1111. 10.1126/science.1220761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouhy F., Ogilvie L. A., Jones B. V., Ross R. P., Ryan A. C., Dempsey E. M., et al. (2014). Identification of aminoglycoside and β-lactam resistance genes from within an infant gut functional metagenomic library. PLoS ONE 9:e108016. 10.1371/journal.pone.0108016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson M. K., Forsberg K. J., Dantas G. (2015). Improved annotation of antibiotic resistance determinants reveals microbial resistomes cluster by ecology. ISME J. 9, 207–216. 10.1038/ismej.2014.106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez I., Georgiou M., Alcaide F., Balas D., Linares J., de la Campa A. G. (1998). Fluoroquinolone resistance mutations in the parC, parE, and gyrA genes of clinical isolates of viridans group streptococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 2792–2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham D. W., Olivares-Rieumont S., Knapp C. W., Lima L., Werner D., Bowen E. (2011). Antibiotic resistance gene abundances associated with waste discharges to the Almendares River near Havana, Cuba. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 418–424. 10.1021/es102473z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith F. (1928). The significance of pneumococcal types. J. Hyg. (Lond.) 27, 113–159. 10.1017/S0022172400031879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmini J., de la Cruz F., Rocha E. P. (2013). Evolution of conjugation and type IV secretion systems. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 315–331. 10.1093/molbev/mss221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakenbeck R. (1998). Mosaic genes and their role in penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Electrophoresis 19, 597–601. 10.1002/elps.1150190423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall B. G., Barlow M. (2004). Evolution of the serine β-lactamases: past, present and future. Drug Resist. Updat. 7, 111–123. 10.1016/j.drup.2004.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson D. J., Ahmed N. (2009). Spirochaetes as intestinal pathogens: lessons from a Brachyspira genome. Gut Pathog. 1:10. 10.1186/1757-4749-1-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford N., Mergeay M. (1973). Interspecific transformation of rifampicin resistance in the genus Bacillus. Mol. Gen. Genet. 120, 151–155. 10.1007/BF00267243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A., Locatelli A., Amoureux L., Depret G., Jolivet C., Gueneau E., et al. (2012). Occurrence of CTX-M Producing Escherichia coli in Soils, Cattle, and Farm Environment in France (Burgundy Region). Front. Microbiol. 3:83. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkey P. M., Jones A. M. (2009). The changing epidemiology of resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64(Suppl. 1), i3–i10. 10.1093/jac/dkp256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss R. D. (1951). Transfer of penicillin resistance in pneumococci by the desoxyribonucleate derived from resistant cultures. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 16, 457–461. 10.1101/SQB.1951.016.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Liu F., Lin I. Y., Gao G. F., Zhu B. (2015). Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 146–147. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00533-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston J. R. (2014). Horizontal gene transfer in the human gastrointestinal tract: potential spread of antibiotic resistance genes. Infect. Drug Resist. 7, 167–176. 10.2147/IDR.S48820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey S. B., Stanton T. B., Jensen N. S., Zuerner R. L. (1997). Purification and characterization of VSH-1, a generalized transducing bacteriophage of Serpulina hyodysenteriae. J. Bacteriol. 179, 323–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyder S. L., Streitfeld M. M. (1978). Transfer of erythromycin resistance from clinically isolated lysogenic strains of Streptococcus pyogenes via their endogenous phage. J. Infect. Dis. 138, 281–286. 10.1093/infdis/138.3.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes A. P., Mercer R. G., Watton D. E., Buckley C. B., Lang A. S. (2012). DNA packaging bias and differential expression of gene transfer agent genes within a population during production and release of the Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent, RcGTA. Mol. Microbiol. 85, 314–325. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janoir C., Podglajen I., Kitzis M. D., Poyart C., Gutmann L. (1999). In vitro exchange of fluoroquinolone resistance determinants between Streptococcus pneumoniae and viridans streptococci and genomic organization of the parE-parC region in S. mitis. J. Infect. Dis. 180, 555–558. 10.1086/314888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen E. C., Schrader H. S., Rieland B., Thompson T. L., Lee K. W., Nickerson K. W., et al. (1998). Prevalence of broad-host-range lytic bacteriophages of Sphaerotilus natans, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 575–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C., Martin B., Fichant G., Polard P., Claverys J. P. (2014). Bacterial transformation: distribution, shared mechanisms and divergent control. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 181–196. 10.1038/nrmicro3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazimierczak K. A., Scott K. P., Kelly D., Aminov R. I. (2009). Tetracycline resistome of the organic pig gut. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 1717–1722. 10.1128/AEM.02206-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp C. W., Dolfing J., Ehlert P. A., Graham D. W. (2010). Evidence of increasing antibiotic resistance gene abundances in archived soils since 1940. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 580–587. 10.1021/es901221x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen B. M., Sinha S., Boyce J. D., Bojesen A. M., Mell J. C., Redfield R. J. (2012). Natural transformation of Gallibacterium anatis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 4914–4922. 10.1128/AEM.00412-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansson E., Fick J., Janzon A., Grabic R., Rutgersson C., Weijdegard B., et al. (2011). Pyrosequencing of antibiotic-contaminated river sediments reveals high levels of resistance and gene transfer elements. PLoS ONE 6:e17038. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. S., Beatty J. T. (2000). Genetic analysis of a bacterial genetic exchange element: the gene transfer agent of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 859–864. 10.1073/pnas.97.2.859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. S., Beatty J. T. (2001). The gene transfer agent of Rhodobacter capsulatus and “constitutive transduction” in prokaryotes. Arch. Microbiol. 175, 241–249. 10.1007/s002030100260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. S., Beatty J. T. (2007). Importance of widespread gene transfer agent genes in alpha-proteobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 15, 54–62. 10.1016/j.tim.2006.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. S., Zhaxybayeva O., Beatty J. T. (2012). Gene transfer agents: phage-like elements of genetic exchange. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 472–482. 10.1038/nrmicro2802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson D. G., de Pedro C., Paxeus N. (2007). Effluent from drug manufactures contains extremely high levels of pharmaceuticals. J. Hazard. Mater. 148, 751–755. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le-Minh N., Khan S. J., Drewes J. E., Stuetz R. M. (2010). Fate of antibiotics during municipal water recycling treatment processes. Water Res. 44, 4295–4323. 10.1016/j.watres.2010.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung M. M., Brimacombe C. A., Spiegelman G. B., Beatty J. T. (2012). The GtaR protein negatively regulates transcription of the gtaRI operon and modulates gene transfer agent (RcGTA) expression in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol. Microbiol. 83, 759–774. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07963.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares J. F., Gustafsson I., Baquero F., Martinez J. L. (2006). Antibiotics as intermicrobial signaling agents instead of weapons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19484–19489. 10.1073/pnas.0608949103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Y., Wang Y., Walsh T. R., Yi L. X., Zhang R., Spencer J., et al. (2015). Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 161–168. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujan R., Zhang Q. Y., Saez Nieto J. A., Jones D. M., Spratt B. G. (1991). Penicillin-resistant isolates of Neisseria lactamica produce altered forms of penicillin-binding protein 2 that arose by interspecies horizontal gene transfer. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35, 300–304. 10.1128/AAC.35.2.300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao D., Luo Y., Mathieu J., Wang Q., Feng L., Mu Q., et al. (2014). Persistence of extracellular DNA in river sediment facilitates antibiotic resistance gene propagation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 71–78. 10.1021/es404280v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marathe N. P., Regina V. R., Walujkar S. A., Charan S. S., Moore E. R., Larsson D. G., et al. (2013). A treatment plant receiving waste water from multiple bulk drug manufacturers is a reservoir for highly multi-drug resistant integron-bearing bacteria. PLoS ONE 8:e77310. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs B. (1974). Genetic recombination in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 71, 971–973. 10.1073/pnas.71.3.971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti E., Variatza E., Balcazar J. L. (2014). Bacteriophages as a reservoir of extended-spectrum β-lactamase and fluoroquinolone resistance genes in the environment. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, O456–O459. 10.1111/1469-0691.12446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. L. (2009). Environmental pollution by antibiotics and by antibiotic resistance determinants. Environ. Pollut. 157, 2893–2902. 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. L. (2008). Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Science 321, 365–367. 10.1126/science.1159483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazaheri Nezhad Fard R., Barton M. D., Heuzenroeder M. W. (2011). Bacteriophage-mediated transduction of antibiotic resistance in enterococci. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 52, 559–564. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel L. D., Young E., Delaney J., Ruhnau F., Ritchie K. B., Paul J. H. (2010). High frequency of horizontal gene transfer in the oceans. Science 330, 50. 10.1126/science.1192243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer R. G., Quinlan M., Rose A. R., Noll S., Beatty J. T., Lang A. S. (2012). Regulatory systems controlling motility and gene transfer agent production and release in Rhodobacter capsulatus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 331, 53–62. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02553.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R. (2009). Replication and conjugative mobilization of broad host-range IncQ plasmids. Plasmid 62, 57–70. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2009.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi S. R., Lee H. H., Spina C. S., Collins J. (2013). Antibiotic treatment expands the resistance reservoir and ecological network of the phage metagenome. Nature 499, 219–222. 10.1038/nature12212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. M., Ahmadi S., Patel S., Gibson M. K., Wang B., Ndao M. I., et al. (2015). Gut resistome development in healthy twin pairs in the first year of life. Microbiome 3:27. 10.1186/s40168-015-0090-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. M., Patel S., Forsberg K. J., Wang B., Bentley G., Razia Y., et al. (2013). Pediatric fecal microbiota harbor diverse and novel antibiotic resistance genes. PLoS ONE 8:e78822. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T., Mizuta S., Suenaga H., Miyazaki K. (2008). Metagenomic screening for bleomycin resistance genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 6803–6805. 10.1128/AEM.00873-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motro Y., La T., Bellgard M. I., Dunn D. S., Phillips N. D., Hampson D. (2009). Identification of genes associated with prophage-like gene transfer agents in the pathogenic intestinal spirochaetes Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, Brachyspira pilosicoli and Brachyspira intermedia. Vet. Microbiol. 134, 340–345. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.09.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munck C., Albertsen M., Telke A., Ellabaan M., Nielsen P. H., Sommer M. O. (2015). Limited dissemination of the wastewater treatment plant core resistome. Nat. Commun. 6, 8452. 10.1038/ncomms9452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musovic S., Oregaard G., Kroer N., Sorensen S. J. (2006). Cultivation-independent examination of horizontal transfer and host range of an IncP-1 plasmid among gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria indigenous to the barley rhizosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 6687–6692. 10.1128/AEM.00013-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann P., Dortet L., Poirel L. (2012). Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm! Trends Mol. Med. 18, 263–272. 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman A., Hansen L. H., Sorensen S. J. (2009). Conjugative plasmids: vessels of the communal gene pool. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364, 2275–2289. 10.1098/rstb.2009.0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsley L. C., Consuegra E. J., Kakirde K. S., Land A. M., Harper W. F., Jr., Liles M. R. (2010). Identification of diverse antimicrobial resistance determinants carried on bacterial, plasmid, or viral metagenomes from an activated sludge microbial assemblage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 3753–3757. 10.1128/AEM.03080-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pehrsson E. C., Forsberg K. J., Gibson M. K., Ahmadi S., Dantas G. (2013). Novel resistance functions uncovered using functional metagenomic investigations of resistance reservoirs. Front. Microbiol. 4:145. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penders J., Stobberingh E. E. (2008). Antibiotic resistance of motile aeromonads in indoor catfish and eel farms in the southern part of The Netherlands. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 31, 261–265. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penders J., Stobberingh E. E., Savelkoul P. H., Wolffs P. F. (2013). The human microbiome as a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Microbiol. 4:87. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron G. G., Whyte L., Turnbaugh P. J., Goordial J., Hanage W. P., Dantas G., et al. (2015). Functional characterization of bacteria isolated from ancient arctic soil exposes diverse resistance mechanisms to modern antibiotics. PLoS ONE 10:e0069533. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletz M. W., McGee L., Van Beneden C. A., Petit S., Bardsley M., Barlow M., et al. (2006). Fluoroquinolone resistance in invasive Streptococcus pyogenes isolates due to spontaneous mutation and horizontal gene transfer. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 943–948. 10.1128/AAC.50.3.943-948.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L., Liard A., Rodriguez-Martinez J. M., Nordmann P. (2005b). Vibrionaceae as a possible source of Qnr-like quinolone resistance determinants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56, 1118–1121. 10.1093/jac/dki371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L., Potron A., Nordmann P. (2012). OXA-48-like carbapenemases: the phantom menace. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 1597–1606. 10.1093/jac/dks121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirel L., Rodriguez-Martinez J. M., Mammeri H., Liard A., Nordmann P. (2005a). Origin of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinant QnrA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 3523–3525. 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3523-3525.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudhomme M., Attaiech L., Sanchez G., Martin B., Claverys J. P. (2006). Antibiotic stress induces genetic transformability in the human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 313, 89–92. 10.1126/science.1127912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiros P., Colomer-Lluch M., Martinez-Castillo A., Miro E., Argente M., Jofre J., et al. (2014). Antibiotic resistance genes in the bacteriophage DNA fraction of human fecal samples. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 606–609. 10.1128/AAC.01684-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesenfeld C. S., Goodman R. M., Handelsman J. (2004). Uncultured soil bacteria are a reservoir of new antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Microbiol. 6, 981–989. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00664.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo L., Manaia C., Merlin C., Schwartz T., Dagot C., Ploy M. C., et al. (2013). Urban wastewater treatment plants as hotspots for antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes spread into the environment: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 447, 345–360. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A. P., Mullany P. (2009). A modular master on the move: the Tn916 family of mobile genetic elements. Trends Microbiol. 17, 251–258. 10.1016/j.tim.2009.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolain J. M., Fancello L., Desnues C., Raoult D. (2011). Bacteriophages as vehicles of the resistome in cystic fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66, 2444–2447. 10.1093/jac/dkr318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmah A. K., Meyer M. T., Boxall A. B. (2006). A global perspective on the use, sales, exposure pathways, occurrence, fate and effects of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in the environment. Chemosphere 65, 725–759. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmieger H., Schicklmaier P. (1999). Transduction of multiple drug resistance of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium DT104. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 170, 251–256. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13381.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolnik P. A., Haselkorn R. (1984). Activation of extra copies of genes coding for nitrogenase in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Nature 307, 289–292. 10.1038/307289a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker N. B., Vlamakis H., Hayes K., Salyers A. A. (2001). Evidence for extensive resistance gene transfer among Bacteroides spp. and among Bacteroides and other genera in the human colon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 561–568. 10.1128/AEM.67.2.561-568.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shousha A., Awaiwanont N., Sofka D., Smulders F. J., Paulsen P., Szostak M. P., et al. (2015). Bacteriophages isolated from chicken meat and the horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 4600–4606. 10.1128/AEM.00872-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibold C., Henrichsen J., Konig A., Martin C., Chalkley L., Hakenbeck R. (1994). Mosaic pbpX genes of major clones of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae have evolved from pbpX genes of a penicillin-sensitive Streptococcus oralis. Mol. Microbiol. 12, 1013–1023. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smillie C., Garcillan-Barcia M. P., Francia M. V., Rocha E. P., de la Cruz F. (2010). Mobility of plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 434–452. 10.1128/MMBR.00020-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solioz M., Yen H. C., Marris B. (1975). Release and uptake of gene transfer agent by Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Bacteriol. 123, 651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer M. O., Dantas G., Church G. M. (2009). Functional characterization of the antibiotic resistance reservoir in the human microflora. Science 325, 1128–1131. 10.1126/science.1176950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparling P. F. (1966). Genetic transformation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to streptomycin resistance. J. Bacteriol. 92, 1364–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt B. G. (1988). Hybrid penicillin-binding proteins in penicillin-resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Nature 332, 173–176. 10.1038/332173a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt B. G., Bowler L. D., Zhang Q. Y., Zhou J., Smith J. M. (1992). Role of interspecies transfer of chromosomal genes in the evolution of penicillin resistance in pathogenic and commensal Neisseria species. J. Mol. Evol. 34, 115–125. 10.1007/BF00182388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt B. G., Zhang Q. Y., Jones D. M., Hutchison A., Brannigan J. A., Dowson C. G. (1989). Recruitment of a penicillin-binding protein gene from Neisseria flavescens during the emergence of penicillin resistance in Neisseria meningitidis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 8988–8992. 10.1073/pnas.86.22.8988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton T. B. (2007). Prophage-like gene transfer agents-novel mechanisms of gene exchange for Methanococcus, Desulfovibrio, Brachyspira, and Rhodobacter species. Anaerobe 13, 43–49. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton T. B., Humphrey S. B., Sharma V. K., Zuerner R. L. (2008). Collateral effects of antibiotics: carbadox and metronidazole induce VSH-1 and facilitate gene transfer among Brachyspira hyodysenteriae strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2950–2956. 10.1128/AEM.00189-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton T. B., Matson E. G., Humphrey S. B. (2001). Brachyspira (Serpulina) hyodysenteriae gyrB mutants and interstrain transfer of coumermycin A(1) resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 2037–2043. 10.1128/AEM.67.5.2037-2043.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminen M., Virta M., Fani R., Fondi M. (2012). Large-scale analysis of plasmid relationships through gene-sharing networks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1225–1240. 10.1093/molbev/msr292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennstedt T., Szczepanowski R., Braun S., Puhler A., Schluter A. (2003). Occurrence of integron-associated resistance gene cassettes located on antibiotic resistance plasmids isolated from a wastewater treatment plant. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 45, 239–252. 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00164-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. M., Nielsen K. M. (2005). Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 711–721. 10.1038/nrmicro1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Cortes G., Millan V., Ramirez-Saad H. C., Nisa-Martinez R., Toro N., Martinez-Abarca F. (2011). Characterization of novel antibiotic resistance genes identified by functional metagenomics on soil samples. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 1101–1114. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubukata K., Konno M., Fujii R. (1975). Transduction of drug resistance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol, macrolides, lincomycin and clindamycin with phages induced from Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Antibiot. 28, 681–688. 10.7164/antibiotics.28.681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boeckel T. P., Brower C., Gilbert M., Grenfell B. T., Levin S. A., Robinson T. P., et al. (2015). Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 5649–5654. 10.1073/pnas.1503141112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boeckel T. P., Gandra S., Ashok A., Caudron Q., Grenfell B. T., Levin S. A., et al. (2014). Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 742–750. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70780-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga M., Kuntova L., Pantucek R., Maslanova I., Ruzickova V., Doskar J. (2012). Efficient transfer of antibiotic resistance plasmids by transduction within methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 clone. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 332, 146–152. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02589.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vien le T. M., Minh N. N., Thuong T. C., Khuong H. D., Nga T. V., Thompson C., et al. (2012). The co-selection of fluoroquinolone resistance genes in the gut flora of Vietnamese children. PLoS ONE 7:e42919. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wintersdorff C. J., Penders J., Stobberingh E. E., Lashof A. M., Hoebe C. J., Savelkoul P. H., et al. (2014). High rates of antimicrobial drug resistance gene acquisition after international travel, the Netherlands. Emerging Infect. Dis. 20, 649–657. 10.3201/eid2004.131718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall J. D., Weaver P. F., Gest H. (1975). Gene transfer agents, bacteriophages, and bacteriocins of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Arch. Microbiol. 105, 217–224. 10.1007/BF00447140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkinson A. J., Murby E. J., Costanzo S. D. (2007). Removal of antibiotics in conventional and advanced wastewater treatment: implications for environmental discharge and wastewater recycling. Water Res. 41, 4164–4176. 10.1016/j.watres.2007.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westbye A. B., Leung M. M., Florizone S. M., Taylor T. A., Johnson J. A., Fogg P. C., et al. (2013). Phosphate concentration and the putative sensor kinase protein CckA modulate cell lysis and release of the Rhodobacter capsulatus gene transfer agent. J. Bacteriol. 195, 5025–5040. 10.1128/JB.00669-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann F., Udikovic-Kolic N., Andrew S., Handelsman J. (2014). Diverse antibiotic resistance genes in dairy cow manure. MBio. 5:e01017. 10.1128/mBio.01017-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woerther P. L., Burdet C., Chachaty E., Andremont A. (2013). Trends in human fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the community: toward the globalization of CTX-M. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 26, 744–758. 10.1128/CMR.00023-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak R. A., Waldor M. K. (2010). Integrative and conjugative elements: mosaic mobile genetic elements enabling dynamic lateral gene flow. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 552–563. 10.1038/nrmicro2382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright G. D. (2010). Antibiotic resistance in the environment: a link to the clinic? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 589–594. 10.1016/j.mib.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright G. D., Poinar H. (2012). Antibiotic resistance is ancient: implications for drug discovery. Trends Microbiol. 20, 157–159. 10.1016/j.tim.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. X., Zhang T., Zhang M., Fang H. H., Cheng S. P. (2009). Characterization and quantification of class 1 integrons and associated gene cassettes in sewage treatment plants. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 82, 1169–1177. 10.1007/s00253-009-1886-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]