Heritable and non-heritable pathways to early callous-unemotional behaviors (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2017 Sep 1.

Abstract

Objective

Callous-unemotional behaviors in early childhood identify children at high risk for severe trajectories of antisocial behavior and callous-unemotional traits that culminate in later diagnoses of conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and psychopathy. Studies have demonstrated high heritability of callous-unemotional traits, but little research has examined specific heritable pathways to earlier callous-unemotional behaviors. Additionally, studies indicate that positive parenting protects against the development of callous-unemotional traits, but genetically informed designs have not been used to confirm that these relationships are not the product of gene-environment correlations.

Method

Using an adoption cohort of 561 families, biological mothers reported their history of severe antisocial behavior. Observations of adoptive mother positive reinforcement at 18 months were examined as predictors of callous-unemotional behaviors when children were 27 months old.

Results

Biological mother antisocial behavior predicted early callous-unemotional behaviors despite having no or limited contact with offspring. Adoptive mother positive reinforcement protected against early callous-unemotional behaviors in children not genetically related to the parent. High levels of adoptive mother positive reinforcement buffered the effects of heritable risk for callous-unemotional behaviors posed by biological mother antisocial behavior.

Conclusions

The findings elucidate heritable and non-heritable pathways to early callous-unemotional behaviors. The results provide a specific heritable pathway to callous-unemotional behaviors and compelling evidence that parenting is an important non-heritable factor in the development of callous-unemotional behaviors. As positive reinforcement buffered heritable risk for callous-unemotional behaviors, these findings have important translational implications for the prevention of trajectories to serious antisocial behavior.

Introduction

Serious antisocial behavior is a key feature of the psychiatric diagnoses of Conduct Disorder in youth and Antisocial Personality Disorder in adults. Based on their high cost, serious antisocial behaviors, such as aggression, violence, and rule breaking, are a major public health concern. For example, a recent study found that each adolescent diagnosed with Conduct Disorder cost society $14,000 more per year than other high-risk adolescents (1). When considering a lifetime prevalence of 10% for Conduct Disorder (2), the financial implications of antisocial behavior are staggering. Additionally, these behaviors have broader, immeasurable occupational, health, social, and emotional costs for perpetrators, victims, and their families. Decades of research have shown that the most severe trajectories of antisocial behavior start in early childhood (3-5). Thus, prevention programs have begun to target younger children when behavior may be more malleable and life course trajectories can be more easily modified (6). However, the effectiveness of interventions continue to be limited and the marked heterogeneity of those with antisocial behavior may contribute to this problem (7). If the etiologies of specific forms of antisocial behavior can be established, then more effective targeted, personalized interventions can be developed.

Callous Unemotional Traits and Behaviors

To address heterogeneity within early-starting antisocial behavior, a specifier was added to the diagnosis of Conduct Disorder in the DSM-5, which assesses the presence of callous-unemotional traits (“limited prosocial emotions” in the DSM-5). Callous-unemotional traits, characterized by low empathy, callousness, and low interpersonal emotions, identify youth with severe, chronic, and stable antisocial behavior (8). Studies demonstrating distinct neural correlates and higher heritability of antisocial behavior in the presence of callous-unemotional traits suggest different etiological pathways to antisocial behavior with, versus without, callous-unemotional traits (9-11). However, as most research on callous-unemotional traits has focused on late childhood and adolescence, we know little about the developmental origins of callous-unemotional traits.

To address this gap, researchers have begun studying callous-unemotional-like behaviors (e.g., lack of guilt, low fear) in the toddler and preschool periods and found these behaviors to identify children with a more severe and homogenous trajectory of early behavior problems (12). Similar to callous-unemotional traits measured in adolescence, early callous-unemotional behaviors are associated with lower guilt, empathy, and moral regulation, and higher proactive aggression (13). These behaviors, measured as early as age 3, predict more severe antisocial behavior and callous-unemotional traits at age 10, over and above other preschool antisocial behaviors (14). Thus, early callous-unemotional behaviors predict more severe antisocial behavior trajectories, the development of callous-unemotional traits in later childhood, and may help identify those in most need for early intervention (15). However, we know little about the etiology of these early emerging behaviors.

Heritable pathways

Twin studies suggest that callous-unemotional traits in middle childhood are highly heritable (estimates range from .45-.67) (9). However, twin studies of callous-unemotional traits have not identified specific heritable parental traits that put children at greater risk for callous-unemotional behaviors (although see 16). An important parental behavior that may signal genetic risk for callous-unemotional behaviors is biological parents' antisocial behavior. Specifically, history of severe antisocial behavior may be indicative of heritable pathways to callous-unemotional behaviors because of the overlap between later callous-unemotional traits, psychopathy, and severe antisocial behavior (8). Though establishing these heritable pathways to callous-unemotional behaviors is critical for understanding the development of callous-unemotional behaviors and severe antisocial behavior more broadly, children typically receive both genes and rearing environments (e.g., parenting) from their parents. Such gene-environment correlations, present in most observational study designs, make it difficult to differentiate genetic from environmental contributions. An adoption design, particularly one in which children are adopted soon after birth, allows for an examination of heritable and non-heritable pathways because biological parents do not provide the rearing environment. Thus, the first goal of the present study was to use an adoption design to examine inherited pathways from biological mothers' antisocial behavior to early child callous-unemotional behaviors.

Non-heritable parenting pathways

Whereas much research on callous-unemotional traits in youth has focused on biological correlates of callous-unemotional traits (10), a growing literature has shown that dimensions of parenting, including harshness and warmth, are important in the development of callous-unemotional traits (17), and even callous-unemotional behaviors as early as age 2 (18). Recent studies suggest that specifics aspects of positive parenting including warmth and positive reinforcement are particularly important for protecting against the development of callous-unemotional behaviors (19) by contingently reinforcing positive child behavior and nurturing a warm parent-child relationship (17, 20). Studies that examine how positive parenting behaviors are related to the development of callous-unemotional behaviors are critical to translational work, because these aspects of parenting are a major malleable target for interventions for antisocial behavior.

However, most typical studies of biological parents rearing their own children cannot rule out the possibility that associations between parenting and child behavior are attributable to genes that influence both parenting and child behavior (16, 21); a notion supported by a monozygotic twin differences study finding little evidence for harsh parenting as a non-shared environmental predictor of callous-unemotional behaviors (16). Thus, genetically informed research is needed to examine if positive parenting directly contributes to the development of callous-unemotional behaviors beyond shared genes. Recently, we showed the first evidence for a non-heritable parenting pathway in the current sample by demonstrating a negative correlation between adoptive parents' positive parenting and children's callous-unemotional behaviors when children were 27 months old. Although this adoption design eliminated passive gene-environment correlation, the findings were cross-sectional. Thus, these results could reflect the impact of evocative gene-environment correlation in which child callous-unemotional behaviors evoke lower parental warmth. Therefore, research is needed to test if dimensions of positive parenting predict lower callous-unemotional behaviors prospectively while controlling for earlier callous-unemotional behaviors and their potential evocative effects, as well as heritable pathways from birth parents. Thus, our second aim was to examine prospective links between positive parenting and callous-unemotional behaviors in early childhood within an adoption study.

Finally, because parenting-focused interventions often aim to reroute the trajectory of children with early forms of antisocial behavior by increasing positive parenting (22, 23), an important question is whether positive parenting can protect against the emergence of callous-unemotional behaviors in the context of high genetic risk for these behaviors. From the perspective of translational research, it is not sufficient to show that positive parenting predicts lower callous-unemotional behaviors over time, but that positive parenting protects youth with the highest genetic risk from developing or maintaining high levels of callous-unemotional behaviors (21). Thus, our third aim was to examine whether the heritable risk posed by antisocial biological mothers could be reduced by adoptive mother positive parenting behaviors.

The current study

In the present study, we tested novel heritable and non-heritable pathways to preschool callous-unemotional behaviors in a sample of 561 children and their families from the Early Growth and Development Study (EGDS), a landmark prospective adoption study with multi-informant measures of biological and adoptive parents, as well as longitudinal measures of early child behavior. The present study builds on a recent paper in which we established the factor structure of a measure of early callous-unemotional behaviors in the EGDS, demonstrated that parent reports of callous-unemotional behaviors at 27 months predicted teacher-reported antisocial behavior at age 7 over and above other dimensions of early antisocial behavior (i.e., oppositional and attention-deficit behaviors), and found a negative cross-sectional correlation between children's callous-unemotional behaviors and adoptive parents' positive parenting when children were 27 months old (15). To further this work and examine heritable, non-heritable, and gene-environment interaction pathways prospectively, we examined whether biological mothers' self-reports of severe antisocial behavior predicted greater adoptive parent reports of child callous-unemotional behaviors at 27 months of age after accounting for other forms of early behavior problems (oppositional and attention-deficit behaviors). Moreover, we incorporated a longitudinal component by testing if observations of adoptive mothers' positive reinforcement when children were 18 months old predicted lower callous-unemotional behaviors at 27 months. Finally, we tested if parenting moderated inherited influences on callous-unemotional behaviors by examining whether the link between biological parent antisocial behavior and child callous-unemotional behaviors was significantly attenuated for children whose adoptive mothers demonstrated high levels of positive reinforcement.

Methods

Sample

The current study used data from the EGDS, a linked set of participants including 561 adopted children (42.8% female), their adoptive parents (567 adoptive mothers, 552 adoptive fathers, including 41 same sex parent families), and their biological mothers (_n_=554) and fathers (_n_=208). Children were adopted within a few days of birth (median=2 days; range=0–91 days), limiting the extent to which biological parents influenced their child via postnatal environmental effects (24). Children of the sample are relatively racially and ethnically diverse (55.6% Caucasian, 19.3% multi-racial, 13% African-American, 10.9% Latino). The sample was recruited in two cohorts. Further information regarding recruitment, consent, procedures, and sample is available elsewhere (24, 25).

Measures

Dimensions of Early Externalizing

We assessed dimensions of early externalizing behaviors at 27 months using adoptive mother report on items from the preschool Child Behavior Checklist (26). Specifically, we used a three-factor model with 17 items that form separable callous-unemotional , oppositional, and attention-deficit behavior scales. This factor structure has been replicated in five independent samples and was the focus of our previous work in EGDS (15) (see Supplemental Methods).

Biological Mother Antisocial Behavior

We assessed biological mother antisocial behavior when adoptive children were 3-6 months old using 47 items from the self-reported computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule (D-DIS) (27, 28). To assess a phenotype closely related to callous-unemotional traits, we also created a measure of “severe antisocial behavior” using the 10 most severe antisocial/illegal items in this measure (see Supplemental Methods).

Adoptive Mother Observed Positive Reinforcement

Adoptive mothers' use of positive reinforcement was observed in the home when children were 18 months old via microsocial coding of a 3-minute clean-up task. Videos of this interaction were coded using the Child Free Play and Compliance Task Coding Manual (K. Pears and M. Ayers, unpublished coding manual, 2005). Mothers' utterances containing positive reinforcement (e.g., “good job”, “thanks for picking that up”) were summed leading to a proportion of positive reinforcement based on the length of the task. Fifteen percent of the tapes were coded by two independent coders; average inter-coder agreement was 88% (overall κ=0.71). This variable was only coded for Cohort 1 (_n_=334) and treated as planned “missing” in all models. Results were identical when only examining Cohort 1 (see Supplemental Table 1).

Covariates

Consistent with previous publications from EGDS, we included child gender, adoption openness (level of contact between biological and adoptive families) (29), and an index of perinatal risk (30) as covariates in all models.

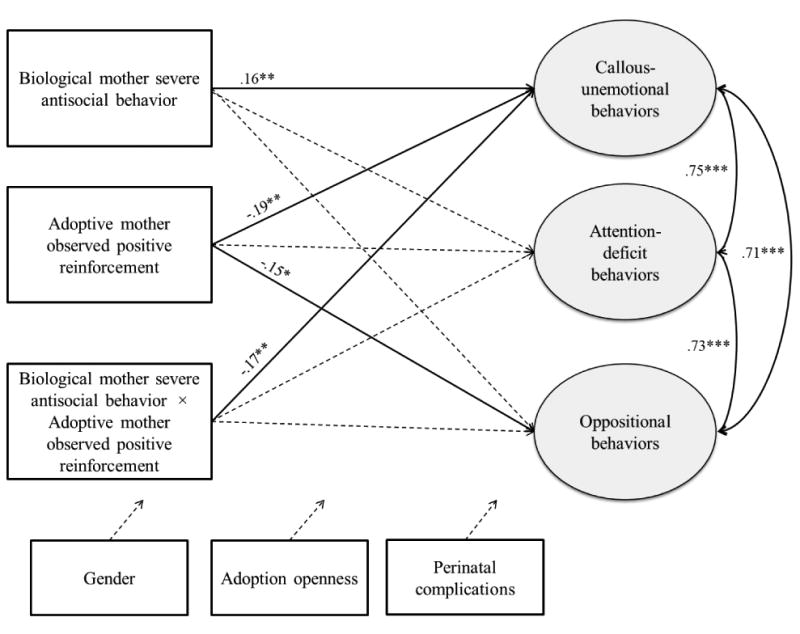

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were carried out in Mplus 7.2 using mean and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation (31) (see Supplemental Methods). We modeled callous-unemotional behaviors within a three factor framework that accounted for the overlap of callous-unemotional with attention-deficit and oppositional behaviors (15). For our first aim, we used structural equation modeling to assess the unique effect of biological mother antisocial behavior on callous-unemotional, oppositional, and attention-deficit behaviors, while controlling for gender, adoption openness, and perinatal complications. For our second aim, we examined whether adoptive mother positive reinforcement predicted callous-unemotional behaviors by adding this variable to the previous model. By testing this stringent model, we examined whether positive reinforcement contributed to callous-unemotional behaviors over and above biological mother's inherited contributions. In a second step, we included callous-unemotional behaviors at 18 months to ensure that any effects were not the result of evocative effects of children's higher earlier callous-unemotional behaviors on parenting. For our third aim, we tested an interaction in which an interaction term (biological mother antisocial behavior × adoptive mother positive reinforcement) was added to the model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Heritable and non-heritable pathways to callous-unemotional behaviors in the toddler years: Biological mother severe antisocial behavior predicts adoptive child callous-unemotional behaviors, but is buffered by adoptive parent positive reinforcement.

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01.

Results

Does biological mother antisocial behavior predict early child callous-unemotional behaviors?

Evidence was found for heritable risk in a main effect of biological mother severe antisocial behavior on child callous-unemotional behaviors at age 27 months (_B_=.13, _SE_=.04, _β_=.16, p<.01). This effect took into account overlap with attention-deficit and oppositional behaviors, as well as the effects of child gender, adoption openness, and perinatal complications. Effects were unique to callous-unemotional behaviors: biological mother antisocial behavior did not predict attention-deficit or oppositional behavior.

Does adoptive mother positive reinforcement predict early child callous-unemotional behaviors?

When observed adoptive mother positive reinforcement was added into the previous model, biological mother antisocial behavior continued to predict child callous-unemotional behaviors, while higher levels of observed adoptive mother positive reinforcement at 18 months uniquely predicted lower child callous-unemotional behaviors at 27 months (_B_=-2.38, _SE_=.94, _β_=-.19, p<.001). This adoptive mother parenting effect remained when controlling for evocative effect of callous-unemotional behaviors at 18 months (_B_=-3.00, _SE_=1.2, _β_=-.19, p<.01).

Does adoptive mother positive reinforcement buffer heritable risk for callous-unemotional behaviors?

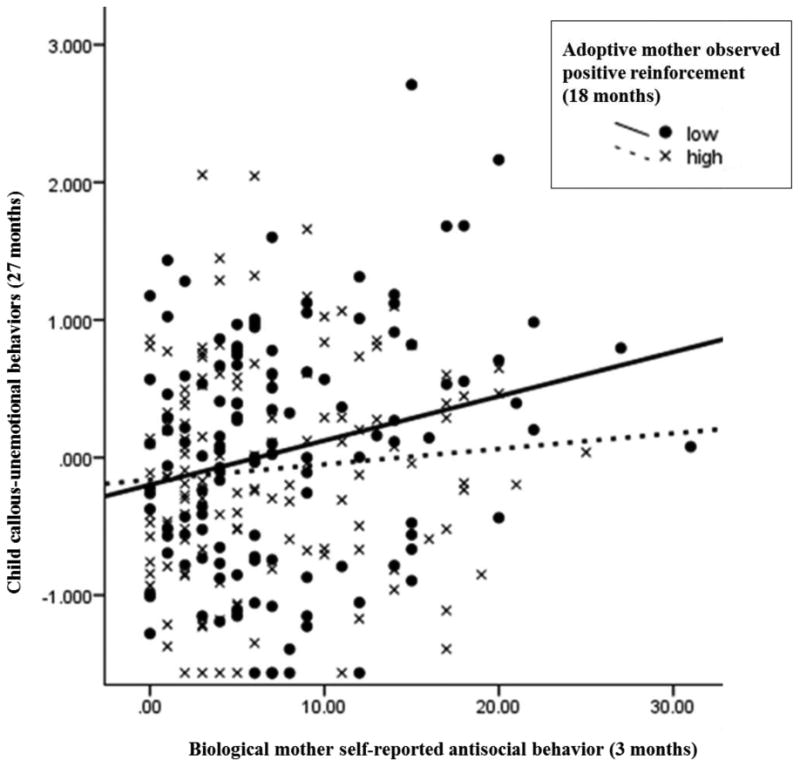

Finally, an interaction was evident between adoptive mother observed positive reinforcement and biological mother antisocial behavior (see Table 1; Figure 1). This interaction (Figure 2), showed that at low, but not high, levels of observed positive reinforcement of adoptive mothers, biological mother antisocial behavior predicted child callous-unemotional behaviors (Low: _B_=.17, _SE_=.08, _β_=.24, p<.05; High: _B_=.01, _SE_=.01, _β_=.01, _p_>.90).

Table 1. Biological mother severe antisocial behavior, adoptive mother positive reinforcement, and their interaction predict callous-unemotional, attention-deficit, and oppositional behavior factor scores when the child is 27 months old.

| Callous-unemotional behaviors 27 months | Attention-deficit behaviors 27 months | Oppositional behaviors27 months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

| Biological mother severe antisocial behavior | .13 | .05 | .16** | .07 | .04 | .09 | .06 | .04 | .08 |

| Adoptive mother observed positive reinforcement | -2.48 | .93 | -.19** | -.84 | .75 | -.07 | -1.92 | .81 | -.15* |

| Interaction term | -1.38 | .52 | -.17** | -.08 | .38 | -.01 | -.37 | .55 | -.05 |

Figure 2.

High levels of adoptive mother positive reinforcement at age 18 months buffer the heritable effects of biological mother antisocial behavior on child callous-unemotional behaviors at age 27 months.

Note. Extracted callous-unemotional behavior factor scores account for covariance with attention-deficit and oppositional behaviors plotted against biological mother self-reported antisocial behavior at high versus low levels of adoptive mother observed positive reinforcement using a median split. Note that to show the full variability in this interaction, the full version (47 items) of biological parent antisocial behavior measure was used for display purposes.

Discussion

We report the first evidence of a specific gene-environment interaction that shapes heritable and non-heritable pathways to early callous-unemotional behaviors with a novel genetically-informed design that allows for stronger conclusions than past studies. We found a specific heritable pathway to callous-unemotional behaviors, as biological mother antisocial behavior predicted child callous-unemotional behaviors in the late toddler period. Our results also demonstrated that parenting prospectively predicts early callous-unemotional behaviors even when parents are not genetically related to the child. Additionally, we found an important gene-environment interaction, whereby more positively reinforcing mothers buffered inherited risk for early callous-unemotional behaviors. In contrast, the combination of both heritable risk and non-heritable risk was related to the highest levels of callous-unemotional behaviors. These findings emphasize both heritable and non-heritable pathways to callous-unemotional behaviors, but that ultimately callous-unemotional behaviors are the product of an interaction between pathways. Evidence for the importance of parenting in the face of inherited risk is critical for parenting-focused intervention efforts, as the results emphasize that positive reinforcement from parents can help to buffer existing genetic risk even in children at high risk for persistent antisocial behavior. This message is incredibly important when discussing a “highly heritable” set of behaviors, because these findings emphasize that heritability is not destiny. Even children with risk for later callous-unemotional behaviors can have their behavior sculpted by high levels of positive reinforcement.

This study is the first, to our knowledge, that specifies a specific heritable pathway for early callous-unemotional behaviors. This pathway was particularly strong when we focused on the most serious maternal antisocial behavior, implying that serious antisocial behavior is a more precise phenotype for understanding heritable risk for early callous-unemotional behaviors. Our findings provide a direct test of one possible heritable pathway suggested by recent findings from Dadds and colleagues (32), who found that paternal psychopathic fearlessness was related to low child eye contact in early childhood during an interaction task. As poor eye contact has been studied as an endophenotype for callous-unemotional traits, this research has been interpreted as supporting a possible genetic link from parental psychopathic traits to mechanisms involved in the development of child callous-unemotional traits (33). Our results add a direct test of a heritable pathway by showing that biological parents' (in this case mothers') severe antisocial behavior predicts early callous-unemotional behaviors, even when that parent is not rearing the child. Given theoretical links between later callous-unemotional traits and interpersonal deficits found in adult psychopathy, it would have been ideal to examine if biological parent psychopathic traits were related to early callous-unemotional behaviors. Unfortunately, this construct has not been measured in the EGDS. However, the more serious antisocial behavior items we did measure may tap a phenotype more closely related to callous-unemotional traits in the parent (8, 34). Future work could elucidate if specific traits associated with psychopathy (e.g., fearlessness) mediate heritable pathways between serious parental antisocial behavior and child callous-unemotional behaviors.

Beyond heritable pathways, our results provide convincing evidence that parenting is important in the development of callous-unemotional behaviors. Through an adoption design and prospective relationship between parental positive reinforcement and child callous-unemotional behaviors, we exclude some important gene-environment correlation confounds present in previous research (17). We measured these processes during a critical developmental period: Parenting during the toddler years becomes increasingly difficult as toddlers gain more mobility and autonomy without the requisite self-regulation skills. Thus, parenting during these years is critical to promoting positive behavior trajectories (6). Empathy, prosocial behavior, and guilt also develop during this period (35), making it an important time in the pathway towards the development of callous-unemotional traits and serious antisocial behavior (15). Moreover, as early callous-unemotional behaviors may also evoke harsher parenting (20), preventing callous-unemotional behaviors early in life may attenuate the development of transactional, cascading coercive cycles of behavior between parents and children that contribute to serious antisocial behavior (36).

Our findings are striking in demonstrating direct effects of positive reinforcement on callous-unemotional behaviors even in the absence of shared inherited vulnerability and evocative effects. Positive reinforcement may be particularly important for preventing callous-unemotional behaviors as a mutually warm relationship can set the foundation for the development of empathic concern (20, 37). Our findings augment studies in early childhood demonstrating that reduced quality of positive affective interactions between parent and child, including lower eye contact, lower observed dyadic warmth, and lower maternal sensitivity, appears to be a risk factor for callous-unemotional behaviors (17, 32, 38). Thus, not surprisingly, high levels of positive reinforcement by adoptive mothers were effective at buffering inherited risk, attenuating the effect of biological mother antisocial behavior on later callous-unemotional behaviors. This interaction emphasizes the malleability of early callous-unemotional behaviors and suggests that positive reinforcement should be emphasized in interventions for early callous-unemotional behaviors (19).

Although our study had several strengths, including an innovative adoption design with a large number of children adopted soon after birth, observational measures of parenting, and assessment of callous-unemotional behaviors at a critical developmental period, it also has a few limitations. We did not have a measure of psychopathy or related constructs measured in biological parents. However, our measure of severe antisocial behavior uniquely predicted callous-unemotional behaviors, and not other dimensions of antisocial behavior, suggesting specificity in this heritable pathway. Second, although there was variability in early child callous-unemotional behaviors, this community sample contained few children already showing clinical levels of antisocial behavior. Third, this study focused on adopted children and participating biological families and adoptive families may not represent the general population: Adoptive families had higher resources (i.e., family income >$100,000 per year) and fewer risk factors, while biological families had lower resources and more risk factors, for antisocial behavior than families in the general population. In translating these findings to the clinic, it is important to consider the relatively high heritability estimates for callous-unemotional traits (39) and our findings of heritable associations between parent antisocial behavior and child callous-unemotional behaviors. Thus, in a “typical” family, children high on callous-unemotional behaviors, who are in the most need of positive parenting, are also more likely to have parents with greater genetic risk, more contextual risk factors for antisocial behavior (e.g., low income, high family stress), who may potentially engage in harsher forms of parenting (16). These parents also may be less likely to seek intervention services. Thus, our adoption findings show “what can be” in a natural experiment, but interventions must contend with the unique challenges of implementing parenting interventions in biological family contexts that may require more engagement and family support to implement sustained positive parenting change. Interventions that meet families in their communities, have regular contact with families, increase social support, and increase motivation for change may be more effective in engaging these families in which children have high heritable and non-heritable risk (22). Finally, our analyses focused on mothers only because we were missing substantial data for biological and adoptive fathers on our variables (only 33% and 37% data for each, respectively). Thus, we may be underestimating heritable effects by exclusively examining biological mothers' contributions and were unable probe the extent to which fathers contribute to pathways to callous-unemotional behaviors. Moreover, it should be noted that parenting was only coded within one EGDS cohort, albeit results were identical using only Cohort 1 data (Supplemental Table 2).

In sum, we found compelling evidence that severe maternal antisocial behavior increases risk for early callous-unemotional behaviors via genetic pathways. However, positive reinforcement from adoptive mothers was a non-heritable predictor of lower callous-unemotional behaviors, and buffered against heritable risk. These findings highlight a specific gene-environment interaction in the development of callous-unemotional behaviors and emphasize that positive parenting can reduce risk for early warning signs of future antisocial behavior. This conclusion emphasizes the importance of positive reinforcement in parenting-based interventions for callous-unemotional behaviors and provides a critical message for parents and others working with children with early antisocial behavior: Early callous-unemotional behaviors are heritable and can identify those at risk for continued antisocial behavior, however, these behaviors are malleable and positive reinforcement from parents can alter these risky pathways.

Supplementary Material

supplamenta

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the biological parents and adoptive families who participated in this study and the adoption agencies who helped with the recruitment of study participants. We also gratefully acknowledge Rand Conger, John Reid, Xiaojia Ge, and Laura Scaramella for their contributions to the larger project.

The Early Growth and Development Study was supported by R01 HD042608 from NICHD, NIDA, and OBSSR, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI Years 1-5: David Reiss; PI Years 6-10: Leslie Leve) and R01 DA020585 from NIDA, NIMH and OBSSR, NIH, U.S. PHS (PI: Jenae Neiderhiser). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. Chris Trentacosta was supported in his efforts by K01 MH082926.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Foster EM, Jones DE. The high costs of aggression: Public expenditures resulting from conduct disorder. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1767–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.061424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Prevalence, subtypes, and correlates of DSM-IV conduct disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2006;36(5):699–710. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw DS, Gilliom M, Ingoldsby EM, Nagin DS. Trajectories leading to school-age conduct problems. Dev Psychol. 2003;39(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ. Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: follow-up at age 26 years. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14(1):179–207. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loeber R, Dishion TJ. Early predictors of male delinquency: A review. Psychol Bull. 1983;94(1):68–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw DS. Future directions for research on the development and prevention of early conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(3):418–28. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.777918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frick PJ, Morris AS. Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(1):54–68. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Kahn RE. Can Callous-Unemotional Traits Enhance the Understanding, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Serious Conduct Problems in Children and Adolescents? A Comprehensive Review. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:1–57. doi: 10.1037/a0033076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viding E, Fontaine NMG, McCrory EJ. Antisocial behaviour in children with and without callous-unemotional traits. J R Soc Med. 2012;105(5):195–200. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Hariri AR. Neuroscience, developmental psychopathology and youth antisocial behavior: Review, integration, and directions for research. Dev Rev. 2013;33:168–223. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blair RJR, Leibenluft E, Pine DS. Conduct Disorder and Callous–Unemotional Traits in Youth. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2207–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1315612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Cheong JW, Dishion TJ, Wilson M. Dimensions of callousness in early childhood: Links to problem behavior and family intervention effectiveness. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25:347–63. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waller R, Hyde LW, Grabell AS, Alves ML, Olson SL. Differential associations of early callous-unemotional, oppositional, and ADHD behaviors: multiple domains within early-starting conduct problems? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56(6):657–66. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waller R, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Wilson MN, Hyde LW. Does early childhood callous-unemotional behavior uniquely predict behavior problems or callous-unemotional behavior in late childhood? 2015 doi: 10.1037/dev0000165. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waller R, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, Ganiban JM, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D, et al. Towards an understanding of the role of the environment in the development of early callous behavior. J Pers. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jopy.12221. Epub ahead of print: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viding E, Fontaine NM, Oliver BR, Plomin R. Negative parental discipline, conduct problems and callous–unemotional traits: Monozygotic twin differences study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195(5):414–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.061192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde LW. What are the associations between parenting, callous-unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(4):593–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Do harsh and positive parenting predict parent reports of deceitful-callous behavior in early childhood? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(9):946–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasalich DS, Witkiewitz K, McMahon RJ, Pinderhughes EE, Group CPPR Indirect effects of the fast track intervention on conduct disorder symptoms and callous-unemotional traits: distinct pathways involving discipline and warmth. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0059-y. epub ahead of print: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waller R, Gardner F, Viding E, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, et al. Bidirectional associations between parental warmth, callous unemotional behavior, and behavior problems in high-risk preschoolers. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:1275–85. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9871-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leve LD, Harold GT, Ge X, Neiderhiser JM, Patterson G. Refining Intervention Targets in Family-Based Research Lessons From Quantitative Behavioral Genetics. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5(5):516–26. doi: 10.1177/1745691610383506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The Family Check-Up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents' positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Dev. 2008;79(5):1395–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazdin AE. Parent management training: Evidence, outcomes, and issues. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(10):1349–56. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199710000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ganiban J, Natsuaki MN, Reiss D. The Early Growth and Development Study: a prospective adoption study from birth through middle childhood. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2013;16(01):412–23. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Ge X, Scaramella LV, Conger RD, Reid JB, et al. The early growth and development study: A prospective adoption design. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10(01):84–95. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achenbach TM, Rescorla L. ASEBA preschool forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blouin AG, Perez EL, Blouin JH. Computerized administration of the diagnostic interview schedule. Psychiatry Res. 1988;23(3):335–44. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(88)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerr DC, Leve LD, Harold GT, Natsuaki MN, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, et al. Influences of biological and adoptive mothers' depression and antisocial behavior on adoptees' early behavior trajectories. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(5):723–34. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9711-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ge X, Natsuaki MN, Martin DM, Leve LD, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, et al. Bridging the divide: openness in adoption and postadoption psychosocial adjustment among birth and adoptive parents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(4):529–40. doi: 10.1037/a0012817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNeil TF, Cantor-Graae E, Sjöström K. Obstetric complications as antecedents of schizophrenia: empirical effects of using different obstetric complication scales. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28(6):519–30. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user's guide: Seventh edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dadds MR, Allen JL, Oliver BR, Faulkner N, Legge K, Moul C, et al. Love, eye contact and the developmental origins of empathy v. psychopathy. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;200(3):191–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyde LW, Waller R, Burt SA, et al. Commentary on Dadds. Improving treatment for youth with Callous-Unemotional traits through the intersection of basic and applied science. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:781–3. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12274. (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patrick CJ. Antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy. In: O'Donohue W, Fowler KA, Lilienfield SO, editors. Personality disorders: Toward the DSM-V. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zahn-Waxler C, Radke-Yarrow M. The origins of empathic concern. Motiv Emotion. 1990;14(2):107–30. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. Am Psychol. 1989;44(2):329–35. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacDonald K. Warmth as a developmental construct: An evolutionary analysis. Child Dev. 1992;63(4):753–73. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bedford R, Pickles A, Sharp H, Wright N, Hill J. Reduced Face Preference in Infancy: A Developmental Precursor to Callous-Unemotional Traits? Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(2):144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viding E, Blair RJR, Moffitt TE, Plomin R. Evidence for substantial genetic risk for psychopathy in 7-year-olds. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(6):592–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

supplamenta