Cordyceps militaris improves tolerance to high intensity exercise after acute and chronic supplementation (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2018 Jan 13.

Abstract

To determine the effects of a mushroom blend containing cordyceps militaris on high intensity exercise after 1- and 3-weeks of supplementation. Twenty-eight individuals (Mean ± SD; Age=22.7 ± 4.1 yrs; Height=175.4 ± 8.7 cm; Weight=71.6 ± 12.0 kg) participated in this randomized, repeated measures, double-blind, placebo-controlled design. Maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), time to exhaustion (TTE), and ventilatory threshold (VT) were measured during a maximal graded exercise test on a cycle ergometer. Relative peak power output (RPP), average power output (AvgP), and percent drop (%drop) were recorded during a 3-minute maximal cycle test with resistance at 4.5% body weight. Subjects consumed 4 g·d−1 mushroom blend (MR) or maltodextrin (PL) for 1 week. Ten volunteers supplemented for an additional 2 weeks. Exercise tests were separated by at least 48-hours and repeated following supplementation periods. One week of supplementation elicited no significant time × treatment interaction for VO2max (p=0.364), VT (p=0.514), TTE (p=0.540), RPP (p=0.134), AvgP (p=0.398), or %drop (p=0.823). After 3-weeks, VO2max significantly improved (p=0.042) in MR (+4.8 ml·kg−1·min−1), but not PL (+0.9 ml·kg−1·min−1). Analysis of 95% confidence intervals revealed significant improvements in TTE after 1- (+28.1 s) and 3-weeks (+69.8 s) in MR, but not PL, with additional improvements in VO2max (+4.8 ml·kg−1·min−1) and VT (+0.7 l·min−1) after 3-weeks. Acute supplementation with a cordyceps militaris containing mushroom blend may improve tolerance to high intensity exercise; greater benefits may be elicited with consistent chronic supplementation.

Keywords: Ergogenic aid, endurance performance, maximal oxygen consumption

Introduction

Cordyceps, a genus of fungus, has been used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat an assortment of conditions including fatigue, respiratory and kidney diseases, renal dysfunction, and cardiac dysfunction (Zhu, Halpern, & Jones, 1998b). More recently, the benefits of cordyceps for athletic performance have been evaluated. Cordyceps first gained attention in 1993, when world record-breaking performances of Chinese female athletes were attributed to a vigorous training and nutrition regimen that involved cordyceps supplementation (Hersh, 1995). Though the performance of these athletes was surrounded with skepticism, interest in potential ergogenic effects of cordyceps has remained. In nature, cordyceps grows as a parasitic fungi on caterpillars (Zhu, Halpern, & Jones, 1998a; Zhu, et al., 1998b), making it rare and expensive. As a result, synthetic cultivation techniques have been more recently utilized for mass production. Cordyceps sinensis, the most commonly supplemented species of cordyceps, has been mass-produced and marketed as Cs-4. Found to have similar components as sinensis, synthetically cultivated cordyceps militaris may yield larger quantities of the active constituents (Kim & Yun, 2005) making it an effective counterpart to sinensis.

Described as a natural exercise mimetic (Kumar et al., 2011), cordyceps is thought to improve performance by increasing blood flow, enhancing oxygen utilization, and acting as an antioxidant (Ko & Leung, 2007; Zhu, et al., 1998a, 1998b). Related to these benefits, a majority of the effects of cordyceps sinensis supplementation have been seen in aerobic performance, showing improvements in maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) and ventilatory threshold (VT) (Chen et al., 2010; Nicodemus, Hagan, Zhu, & Baker, 2001; Yi, Xi-zhen, & Jia-shi, 2004). Indirectly, there may also be potential effects of cordyceps supplementation on high intensity performance. Enhanced oxygen utilization and blood flow, especially to the liver and non-exercising skeletal muscle, may enhance lactate clearance. This may allow athletes to maintain a higher intensity of exercise, while the reduction of oxidative stress from high intensity exercise may delay fatigue (Adams & Welch, 1980; Brooks, 1985; Mizuno et al., 2008; Rowell et al., 1966). When combined with three weeks of high intensity interval training, a pre-workout blend containing cordyceps sinensis had positive effects on critical velocity, an aerobic performance measure (Smith, Fukuda, Kendall, & Stout, 2010). Despite potential benefits, a number of studies have found no benefits of cordyceps supplementation on aerobic and anaerobic performance (Colson et al., 2005; Earnest et al., 2004; Parcell, Smith, Schulthies, Myrer, & Fellingham, 2004). To date, research on the ergogenic effects of cordyceps is limited and inconclusive as to its benefits to exercise.

Available studies utilizing cordyceps vary considerably in dosing and supplementation duration. Higher doses of cordyceps sinensis (3 g·d−1) have resulted in significant benefits on VO2max and VT (Nicodemus, et al., 2001; Yi, et al., 2004); doses of 4.5 g·d−1 also significantly augmented VO2max, VT, in addition to delaying lactate production and enhancing metabolic efficiency (Nicodemus, et al., 2001). Lower doses (1 g·d−1) have been less likely to result in significant effects, except for situations of prolonged supplementation (12 weeks) (Chen, et al., 2010; Colson, et al., 2005; Earnest, et al., 2004). Based on available data, higher dosages (3 – 4.5 g·d−1) in combination with longer interventions (5 – 6 weeks) seem to produce the best results, but the acute effects of a higher dosage are currently unclear. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to determine the acute (1-week) effects of a cordyceps militaris (4 g·d−1) containing mushroom blend on aerobic performance, including oxygen kinetics (VO2max, VT), and time to exhaustion (TTE). A secondary purpose was to explore the ergogenic potential on anaerobic performance (relative peak power [RPP], average power [AvgP], and percent power drop [%drop]). Lastly, an exploratory aim was to evaluate a longer duration (3-weeks) of cordyceps militaris supplementation.

Methods

Experimental Design

Prior to testing, all participants signed a written informed consent approved by the University's Institutional Review Board and underwent a 12-lead electrocardiogram and physical examination. Once cleared for participation, baseline testing consisted of a maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) test and a three-minute maximal cycle test, separated by a minimum of 48 hours and no more than one week. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design, participants were randomly assigned, using Random Allocation Software (Version 1.0.0; Isfahan, Iran), into one of two treatment groups: mushroom (MR) or placebo (PL). Subjects ingested either 1.3 grams of a mushroom blend (PeakO2, Compound Solutions, Inc., USA; Table 3) or 1.3 grams of maltodextrin (PL) in the form to two capsules, taken orally three times per day (4 grams daily) for one week (Phase I). Capsules were identical in color and taste and packaged in white opaque bottles, randomized and coded by the manufacturer. Participants were randomized using block randomization with codes de-identified from separate white envelopes. Following the one-week supplementation period, baseline exercise tests were repeated. A sub-set of participants volunteered to complete an additional two weeks of supplementation (Phase II), for a total of three weeks of supplementation, followed by exercise testing.

Table 3.

PeakO2 Mushroom Blend and Placebo Ingredient List.

| PeakO2 Mushroom Blend | Placebo |

|---|---|

| Cordyceps militaris (Northern Cordyceps) | Maltodextrin Hemp Protein Powder |

| Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi) | |

| Pleurotus eryngii (King Trumpet) | |

| Lentinula edodes (Shiitake) | |

| Hericium erinaceus (Lion's Mane) | |

| Trametes versicolor (Turkey Tail) |

Subjects

A total of 35 subjects were recruited and contacted for participation in the study. Five potential subjects were excluded after failing to meet inclusion criteria as outlined below. A total of 30 subjects were randomized to one of two treatment groups (MR or PL). Two subjects did not complete the entire study protocol due to injuries unrelated to the current study.

Therefore, 28 adults (16 males; 12 females), between the ages of 18-35 years completed phase I of this study (Table 1). Ten subjects (4 males; 6 females) volunteered to complete phase II and receive supplementation for an additional two weeks (Table 2). A medical history form and physical screening were used to assess subjects for inclusion. All subjects were recreationally active, defined by an average of five hours per week of structured exercise, had been involved in an exercise program (≥ 3 days/week) for a minimum of one year, and had no reported musculoskeletal injuries. Subjects agreed to abstain from caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, and exercise 24 hours prior to testing days, but otherwise maintain their normal diet and exercise routine for the duration of the study. Subjects were excluded from participation if they had a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 28 kg·m−2, had consumed beta-alanine, creatine, beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate (HMB), carnosine, or taurine supplements within 12 weeks prior to enrollment, or were allergic to mushrooms. This project was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02075892).

Table 1.

Phase I supplementation subject characteristics. (Mean ± standard deviation [SD])

| Treatment | Age (yrs) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | BMI (kg·m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mushroom (n=13) | 22.2 ± 3.9 | 176.0 ± 8.7 | 71.2 ± 9.6 | 23.1 ± 2.1 |

| Placebo (n=15) | 23.1 ± 4.3 | 174.9 ± 9.0 | 71.7 ± 14.0 | 23.3 ± 3.2 |

Table 2.

Phase II supplementation subject characteristics (Mean ± SD).

| Treatment | Age (yrs) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | BMI (kg·m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mushroom (n=6) | 21.7 ± 2.7 | 176.3 ± 9.7 | 75.3 ± 10.2 | 24.2 ± 2.0 |

| Placebo (n=4) | 21.0 ± 2.0 | 175.1 ± 4.9 | 74.5 ± 12.7 | 24.2 ± 3.3 |

Procedures

Maximal Oxygen Consumption (VO2max) Test

Subjects performed a VO2max test on an electronically-braked cycle ergometer (Lode, Gronigen, The Netherlands) in order to determine VO2max, TTE, and VT. Upon arrival, subjects were fitted with a heart rate monitor (Polar Electro Inc., Lake Success, NY). Subjects were then fitted to the cycle ergometer. The handlebars were adjusted to a comfortable position with seat height adjusted so that there was no more than an approximate 15-degree bend in the knee on full extension. Once positioned, subjects were fitted with headgear and mouthpiece to collect respiratory gases throughout the test. The protocol included a two-minute warm-up at a self-selected pace (between 60-80 rpm) with an initial power output of 20 watts (W), after which the workload automatically increased 1 watt (W) every 3 seconds. Subjects were instructed to maintain a pedal cadence between 60-80 rpm until they reached volitional fatigue. Respiratory gases were analyzed breath-by-breath via open-circuit spirometry (Parvo Medics TrueMax 2400®, Salt Lake City, UT) and VO2 values were averaged every 15 seconds with the highest value recorded as the VO2max. The test was considered a VO2max if two of the following criteria were met: 1) a plateau in the heart rate (HR) or a HR within 10% of the age-predicted maximum HR, 2) a plateau in VO2 (an increase of no more than 150 ml/min−1), 3) a respiratory exchange ratio (RER) value greater than 1.15 (Medicine, 2013). Test-retest reliability for the VO2peak protocol demonstrated reliable between-day testing with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.98 and standard error of the measurement (SEM) of 1.74 ml·kg−1·min−1.

Three-Minute Maximal Cycle Test

At least 24 hours after the VO2max test, participants returned to the laboratory to complete the three-minute cycle test. After being fitted with a HR monitor, subjects were fitted to a Monark friction-braked cycle ergometer (Ergomedic 894 E; Monark, Vansbro, Sweden). Following a three-minute self-paced warm-up with 0.5 kg load, the load was removed from the flywheel. Subjects were instructed to increase pedal cadence to as hard and fast as possible with an unloaded flywheel. Once a steady speed of at least 120 rpm was reached, a load of 4.5% of body weight was applied, while subjects continued to pedal as hard as possible for three minutes (Bergstrom et al., 2012). Subjects were not given time updates throughout the test, but were verbally encouraged to pedal as hard and fast as possible for the entirety of the test. Peak power output, AvgP, and %drop were recorded throughout the test using default software (Monark Anaerobic Test Software Version 3.2.7.0; Monark, Vansbro, Sweden). Data was processed by applying a one second filer to the peak power values. Relative peak power output was calculated as the maximum output achieved during the test after the filter was applied divided by body weight (W∙kg−1). Percent power drop was calculated from the resulting maximum and minimum values (%drop=((maximum-minimum)/maximum)*100).

Supplementation

Following baseline testing, subjects were randomized to either mushroom blend (MR) or placebo (PL) treatment groups. Subjects were given capsules containing either mushroom blend (PeakO2, Compound Solutions, Inc., USA; Table 3), containing dehydrated, finely milled, cordyceps mycelial biomass powder cultured from organic oats, and a variety of other mushroom species that have potential anti-oxidant/anti-inflammatory properties , or a placebo (PL) containing maltodextrin and hemp protein. Subjects were instructed to consume two capsules (1.3 grams), three times per day for one week to achieve a 4 gram daily dosage of cordyceps militaris. Individuals completed supplementation within 24-hours of post-testing. After completing all post-testing, subjects who volunteered to complete phase II were given a second supply to continue their respective supplementation for an additional two weeks. Compliance was monitored by the return of supplement bottles at the end of each supplemental phase. Thirty-one out of 35 subjects in phase I and eight out of ten subjects in phase II had 100% compliance. No individual subject had less than 90% compliance for either phase. Treatments remained blinded until both phases reached full completion and remained blinded until all statistical analyses were performed.

Statistical Analysis

Separate mixed factorial (treatment × time) ANOVAs with Bonferroni post hoc comparisons were used to analyze differences in primary variables (VO2max, VT, TTE, RPP, AvgP, %drop). Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI; Mean ± 1.96 × SEM) were also completed to assess change from pre to post. If the 95% CI included zero, the mean change score was considered as not different from zero, which was interpreted as no statistically significant change. If the 95% CI interval did not include zero, the mean change score was considered statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). An initial intent to treat analysis was performed on all 30 subjects. Results did not differ from the explanatory analyses, therefore only the explanatory analysis on 28 subjects is included. Data was analyzed using SPSS (Version 21, IBM, Armonk, NY); Microsoft Excel 2013 (Version 15.0.4753.1003, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) was used to calculate and analyze 95% CI.

For powering of the current study, a repeated measures within-between interaction factor was used to identify a necessary sample of 25, with an effect size of 0.55, power of 0.95, for two groups, with a correlation of 0.2 (reported from (Kolkhorst, Rezende, Levy, & Buono, 2004; Nagata, Tajima, & Uchida, 2006; Smith, et al., 2010)). Calculations were performed using G-Power statistical software (G*Power Version 3.1.9.2).

Results

Maximum Oxygen Consumption

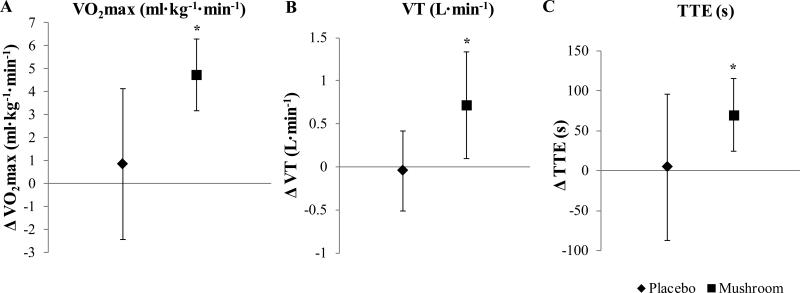

After one week of supplementation with a cordyceps containing mushroom blend (Phase I), there was no significant time × treatment interaction for VO2max (p=0.364). There was a main effect for time for VO2max (p=0.011), with significant increases observed in in both MR (47.7 ± 9.4 to 49.0 ±8.6 ml·kg−1·min−1) and PL (46.4 ± 7.9 to 48.9 ± 8.1 ml·kg−1·min−1). There was no main effect for treatment (p=0.822). Analysis of 95% CI showed a significant increase in VO2max for PL, but not for MR. After three weeks of supplementation (Phase II), there was a significant time × treatment interaction (p=0.042). Post-hoc pairwise comparison demonstrated a significant increase in VO2max from pre to post for MR (44.0 ± 10.5 to 48.8 ± 11.2 ml·kg−1·min−1); there was no significant change for placebo (45.0 ± 12.5 to 45.9 ± 9.9 ml·kg−1·min−1). Analysis of 95% CI showed a significant increase in VO2max for MR, but not for PL (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Phase II changes in performance measures (A) maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), (B) ventilatory threshold (VT), and (C) time to exhaustion (TTE) presented as 95% confidence intervals (Mean ± (1.96 × SEM)).

*indicates a significant improvement, as determined by 95% CI

Ventilatory Threshold

After one week of supplementation, there was no significant time × treatment interaction for VT (p=0.514). There was no main effect for time (p=0.052) or treatment (p=0.868). Analysis of 95% CI showed no significant changes for either treatment group. After three weeks of supplementation, there was no time × treatment interaction (p=0.301), and no main effect for time (p=0.071) or treatment (p=0.407). Analysis of 95% CI showed a significant increase in VT for MR (1.7 ± 0.3 to 2.4 ± 1.0 l·min−1), but not for PL (2.4 ± 0.9 to 2.4 ± 0.7 l·min−1) (Figure 1B).

Time to Exhaustion

After one week of supplementation, there was no significant time × treatment interaction for TTE (p=0.540). There was a significant main effect for time (p=0.046) with both groups increasing form pre to post. There was no main effect for treatment (p=0.721). Analysis of 95% CI revealed a significant increase in TTE in MR (855.1 ± 135.9 to 883.2 ± 132.7 s), but not PL (818.2 ± 250.0 to 876.1 ± 169.7 s). After three weeks of supplementation, there was no time × treatment interaction (p=0.261), no main effect for time (p=0.192) or treatment (p=0.945). Analysis of 95% CI revealed a significant increase in TTE for MR (851.7 ± 192.2 to 921.5 ± 184.2 s), but not PL (880.0 ± 204.7 to 884.6 ± 147.5 s) (Figure 1C).

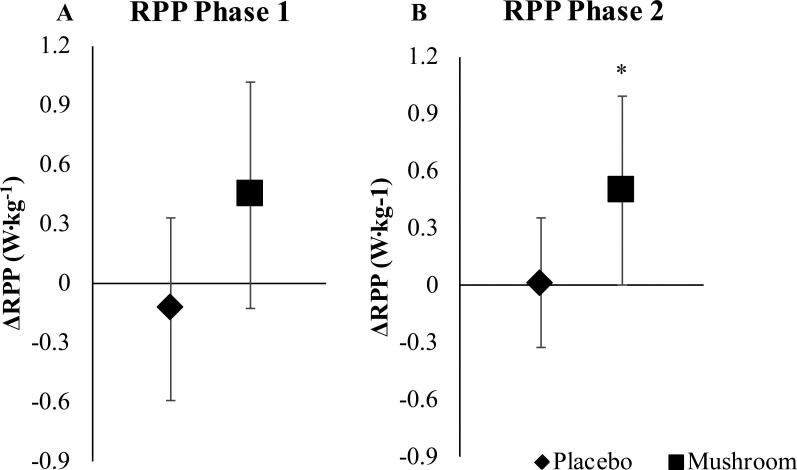

Relative Peak Power

After one week of supplementation, there was no significant time × treatment interaction (p=0.134), and no main effect for time (p=0.392) or treatment (p=0.774) for RPP. Analysis of 95% CI revealed no significant changes for either group, though RPP did increase in MR (5.9 ± 1.0 to 6.3 ± 1.8 W·kg−1) and decreased in PL (6.0 ± 0.8 to 5.9 ± 1.0 W·kg−1) (Figure 2A). After three weeks of supplementation, there was no time × treatment interaction (p=0.380), main effect for time (p=0.356), or treatment (p=0.599). Analysis of 95% CI revealed a significant increase in RPP for MR (5.9 ± 1.1 to 6.4 ± 1.8 W·kg−1), but not for PL (5.7 ± 0.9 to 5.7 ± 0.5 W·kg−1) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Change in RPP for Phase I (A) and Phase II (B) presented as 95% CI (Mean ± (1.96 × SEM)).

*indicates a significant improvement, as determined by 95% CI

Average Power

After one week of supplementation, there was no time × treatment interaction (p=0.398), and no main effect for time (p=0.667) or treatment (p=0.851) for AvgP. Analysis of 95% CI revealed no significant changes in AvgP pre to post for MR or PL. After three weeks of supplementation, there was no time × treatment interaction (p=0.627), no main effect for time (p=0.199), or treatment (p=0.647). Analysis of 95% CI revealed no significant changes in AvgP pre to post for MR or PL.

Percent Power Drop

After one week of supplementation, there was no time × treatment interaction (p=0.832), main effect for time (p=0.212), or treatment (p=0.829) for %drop. Analysis of 95% CI revealed no significant changes in %drop pre to post for MR or PL. After three weeks of supplementation, there was no time × treatment interaction (p=0.212) and no main effect for treatment (p=0.590) for %drop. There was a significant main effect for time (p=0.046), with decreases in %drop for both MR (72.0 ± 6.3 to 70.7 ± 8.1 %) and PL (76.1 ± 3.9 to 71.3 ± 6.7 %). Analysis of 95% CI revealed a significant decrease in %drop pre to post for PL, but not for MR.

Discussion

To date, minimal research evaluating the use of cordyceps militaris on human performance exists, especially for an acute time-period. Results of the current study demonstrate that one week of supplementation with a cordyceps militaris containing mushroom blend at 4 g·d−1 did not significantly improve performance compared to a placebo. However, an exploratory three week supplementation period resulted in significant improvements in maximal oxygen consumption, with potential improvements in ventilatory threshold and time to exhaustion, suggesting the potential for greater benefits with chronic supplementation. On average, there were no significant observed increases in RPP after one week of supplementation, but after three weeks of supplementation, there was a significant increase in RPP suggesting that investigations of the benefits of cordyceps militaris on anaerobic performance should be explored. Although minimal benefits were observed with acute supplementation of a cordyceps militaris containing mushroom blend, consistent supplementation at 4 g·d−1 may benefit tolerance to high intensity exercise, potentially eliciting performance gains through increases in training intensity and delaying fatigue.

Previous studies investigating the performance benefits of cordyceps have primarily utilized a synthetically cultivated version of cordyceps sinensis, known as Cs-4. Cordyceps militaris is another synthetically cultivated species that has been found to exhibit similar functions as sinensis, potentially making them interchangeable in their use (Shrestha, Han, Sung, & Sung, 2012; Zhou, Gong, Su, Lin, & Tang, 2009). However, militaris has been shown to yield greater amounts of active constituents (Kim & Yun, 2005), which may lead to more pronounced performance benefits. Benefits to aerobic performance with cordyceps supplementation may be attributed to enhanced blood flow and oxygen utilization, by increasing vasodilation and metabolic efficiency (Chiou, Chang, Chou, & Chen, 2000; Feng, Zhou, Feng, & Shuai, 1987; Lou, Liao, & Lu, 1986; Zhu, et al., 1998a, 1998b). Enhanced oxygen delivery and utilization may increase exercise tolerance, raising the anaerobic threshold and delaying the onset of fatigue. In the current study, one week of supplementation with a higher dosage (4 grams) of cordyceps militaris had no significant effect on performance outcomes compared to a control. While there was no difference between groups after one week, there was a significant improvement in TTE in the supplement group (3.2%) pre to post, potentially indicating an increase in exercise tolerance and delay in fatigue. There was a significant main effect for time for VO2max and TTE, with both groups increasing pre to post. Yet, despite a greater increase on average (6.6%), there was not a significant improvement in TTE in the control group, related to high variability within the group. Other studies in elite cyclists have shown no effects of cordyceps sinensis on aerobic performance after acute intervention periods (13 – 15 days) (Colson, et al., 2005; Earnest, et al., 2004). Compared to the lower dosages (1 – 2 g) in these previous studies, potential benefits observed after one week of supplementation in the current study may be related to the higher dosage.

In older adults, cordyceps supplementation improved ventilatory threshold (8.5%) and metabolic threshold (10.5%), after 1 g·d−1 for twelve weeks (Chen, et al., 2010), and improved VO2max (6.7%) and anaerobic threshold (12.6%) at 3 g·d−1 for six weeks (Yi, et al., 2004) suggesting potential benefits with chronic supplementation. After three weeks of supplementation in the current study, there were significant increases in VO2max (10.9%) compared to a control and a significant increase in VT (41.2%) and TTE (8.2%) pre to post. Improvements in VO2max and VT are consistent with a similar study in male endurance athletes, where VO2max and VT increased after cordyceps sinensis supplementation at a similar dosage (4.5 g·d−1) (Nicodemus, et al., 2001). In the same study, respiratory exchange ratio was lower throughout submaximal exercise with supplementation, indicating cordyceps sinensis may potentially enhance fat oxidation. In rats, cordyceps sinensis upregulated skeletal muscle metabolic regulators, promoted angiogenesis, and increased glucose uptake, improving endurance capacity and delaying fatigue (Kumar, et al., 2011). Mitochondrial biogenesis was increased in the rat model, which may have a subsequent influence on fatty acid oxidation and glycogen turnover, increasing ATP availability and improving performance. Cordyceps has also been shown to act as an antioxidant, potentially reducing exercise induced oxidative stress (Ko & Leung, 2007), and improving the ability to withstand high intensity exercise. While a cordyceps militaris containing mushroom blend did improve the ability to withstand high intensity exercise to a moderate degree, it should be noted that the MR group had a lower, but not significantly different (p>0.05), baseline VT (1.7 l·min−1) compared to PL (2.4 l·min−1) and post-test values between groups were identical (2.4 min−1). In the current study, evaluation of three weeks of a cordyceps militaris containing mushroom blend was an exploratory aim. Despite the limited sample size, based on the duration and amount of cordyceps reported from previous studies, and with respect to the present study, an ergogenic response is likely dose dependent with 3 - 4 g·d−1, with a more chronic consumption resulting in a greater ergogenic benefits. These results should be further verified in a larger sample size.

Upregulation of energy producing pathways, enhanced blood flow, and increased intracellular ATP may also increase the ability to reach and maintain exercise at higher intensities. Cordyceps use has previously been shown to delay lactate accumulation (Nicodemus, et al., 2001) and improve lactate transport (Kumar, et al., 2011), however, data supporting direct effects of cordyceps militaris on high intensity exercise performance is limited. Smith et al. (2010) previously investigated the effects of a pre-workout supplement containing cordyceps sinensis (2.5 g) on high intensity running performance, suggesting no significant benefit to anaerobic running capacity. Similarly, in trained cyclists, sinensis supplementation had no effects on peak power output achieved during a graded maximal exercise test (Earnest, et al., 2004). Previous results may be attributed to a lower dosage of cordyceps sinensis, as results of the current study allude to potential benefits of cordyceps militaris for high intensity performance, with an observed increase in RPP compared to a decrease in the control after one week, and a significant increase in RPP after three weeks. Despite potential, results of the current study do not support a strong benefit of cordyceps militaris supplementation on achieving a higher AvgP, RPP, or attenuating the loss of power. Longer supplementation or a higher dosage of cordyceps may be necessary to elicit more substantial improvements.

To date, minimal research exists on the use of cordyceps for athletic performance. Existing literature is highly variable with dosing strategies, ranging from small acute doses to longer loading phases. The present study addresses these gaps in the literature by evaluating effects of a larger acute dose (4 g·d−1 for 1 week) and a more chronic dose (4 g·d−1 for 3 weeks). Previous small acute doses, ranging from 1.0 – 2.5 grams, have failed to show an ergogenic effect. In contrast, larger doses (4.5 g·d−1) have shown benefits to maximal aerobic exercise (Nicodemus, et al., 2001). When implementing a loading phase of 2 g of cordyceps for 4 – 6 days, followed by a 1 g maintenance dose (7 – 11 days), there were no significant effects on performance (Colson, et al., 2005; Earnest, et al., 2004). Based on available data, a loading phase at a higher dosage (> 4 g) may enhance the acute effects of cordyceps. In animal models, cordyceps miltaris is considered to be non-toxic at doses of up to 4 g·kg−1 (Gong et al., 2003), while doses of up to 6 g·d−1 have led to positive results in clinical and diseased populations (Zhu, et al., 1998a), making a higher dosage potentially feasible. However, as the current study did not implement a loading period and the overall amount of cordyceps consumed was greater than previous studies, it is difficult to discern if a loading period is beneficial or necessary. More research is needed to identify optimal dosing strategies to improve exercise performance, especially at a higher dose.

In conclusion, one week of supplementation with a cordyceps militaris containing mushroom blend had minimal benefits to high intensity aerobic and anaerobic exercise. Greater benefits may be elicited with longer supplementation, with potential improvements in oxygen consumption, ventilatory threshold, time to exhaustion, and relative peak power output at a dosage of 4 g·d−1. Future studies should aim to establish dosage for maximal ergogenic benefits.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Disruptive Nutrition, Burlington, NC. The project described was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR001109. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. This study was designed by ASR. Testing and data collection was done by EJR, ETT, KRH, ASR, and MGM. Data analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation were undertaken by KRH and ASR. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams RP, Welch HG. Oxygen uptake, acid-base status, and performance with varied inspired oxygen fractions. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1980;49(5):863–868. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom HC, Housh TJ, Zuniga JM, Camic CL, Traylor DA, Schmidt RJ, Johnson GO. A new single work bout test to estimate critical power and anaerobic work capacity. J Strength Cond Res. 2012;26(3):656–663. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822b7304. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822b7304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks GA. Anaerobic threshold: review of the concept and directions for future research. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 1985;17(1):22–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Li Z, Krochmal R, Abrazado M, Kim W, Cooper CB. Effect of Cs-4®(Cordyceps sinensis) on exercise performance in healthy older subjects: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2010;16(5):585–590. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou W-F, Chang P-C, Chou C-J, Chen C-F. Protein constituent contributes to the hypotensive and vasorelaxant acttvtties of cordyceps sinensis. Life Sciences. 2000;66(14):1369–1376. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00445-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colson SN, Wyatt FB, Johnston DL, Autrey LD, FitzGerald YL, Earnest CP. Cordyceps sinensis-and Rhodiola rosea-based supplementation in male cyclists and its effect on muscle tissue oxygen saturation. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2005;19(2):358–363. doi: 10.1519/R-15844.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnest CP, Morss GM, Wyatt F, Jordan AN, Colson S, Church TS, Lucia A. Effects of a commercial herbal-based formula on exercise performance in cyclists. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2004;36(3):504–509. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000125157.49280.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng M, Zhou Q, Feng G, Shuai J. Vascular dilation by fermented mycelia of Cordyceps sinensis in anesthetized dogs. J. Chinese Materia Medica. 1987;12:745–749. [Google Scholar]

- Gong C, Xu C, Yang K, Chen G, Pan Z, Wu W. Studies on toxicities of silkworm Cordyceps militaris. Edible Fungi of China. 2003;23(1):46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hersh P. The Rise and Fall of Ma's Army: World Records, Questions will Last for Decades, Chicago Tribune. 1995 Aug 3; 1995 Retrieved from http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1995-08-03/sports/9508030118_1_chinese-women-world-records-blood-and-caterpillar-fungus.

- Kim H, Yun J. A comparative study on the production of exopolysaccharides between two entomopathogenic fungi Cordyceps militaris and Cordyceps sinensis in submerged mycelial cultures. Journal of applied microbiology. 2005;99(4):728–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko KM, Leung HY. Enhancement of ATP generation capacity, antioxidant activity and immunomodulatory activities by Chinese Yang and Yin tonifying herbs. Chin Med. 2007;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-2-3. doi: 1749-8546-2-3 [pii]10.1186/1749-8546-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolkhorst FW, Rezende RS, Levy SS, Buono MJ. Effects of sodium bicarbonate on VO2 kinetics during heavy exercise. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2004;36(11):1895–1899. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000145440.55346.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Negi PS, Singh B, Ilavazhagan G, Bhargava K, Sethy NK. Cordyceps sinensis promotes exercise endurance capacity of rats by activating skeletal muscle metabolic regulators. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136(1):260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.040. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.040S0378-8741(11)00292-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y, Liao X, Lu Y. Cardiovascular pharmacological studies of ethanol extracts of Cordyceps mycelia and Cordyceps fermentation solution. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs. 1986;17(5):17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Medicine A. C. o. S. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K, Tanaka M, Nozaki S, Mizuma H, Ataka S, Tahara T, Kuratsune H. Antifatigue effects of coenzyme Q10 during physical fatigue. Nutrition. 2008;24(4):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata A, Tajima T, Uchida M. Supplemental anti-fatigue effects of Cordyceps sinensis (Tochu-Kaso) extract powder during three stepwise exercise of human. 2006;55(Supplement):S145–S152. 体力科学. [Google Scholar]

- Nicodemus K, Hagan R, Zhu J, Baker C. Supplementation with Cordyceps Cs-4 fermentation product promotes fat metabolism during prolonged exercise. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2001;33:164. [Google Scholar]

- Parcell AC, Smith JM, Schulthies SS, Myrer JW, Fellingham G. Cordyceps sinensis (CordyMax Cs-4) supplementation does not improve endurance exercise performance. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism. 2004;14(2):236–242. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.14.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, Kraning K, Evans T, Kennedy JW, Blackmon J, Kusumi F. Splanchnic removal of lactate and pyruvate during prolonged exercise in man. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1966;21(6):1773–1783. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1966.21.6.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha B, Han S-K, Sung J-M, Sung G-H. Fruiting body formation of Cordyceps militaris from multi-ascospore isolates and their single ascospore progeny strains. Mycobiology. 2012;40(2):100–106. doi: 10.5941/MYCO.2012.40.2.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AE, Fukuda DH, Kendall KL, Stout JR. The effects of a pre-workout supplement containing caffeine, creatine, and amino acids during three weeks of high-intensity exercise on aerobic and anaerobic performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2010;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-7-10. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-7-101550-2783-7-10 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi X, Xi-zhen H, Jia-shi Z. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial and assessment of fermentation product of Cordyceps sinensis (Cs-4) in enhancing aerobic capacity and respiratory function of the healthy elderly volunteers. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2004;10(3):187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Gong Z, Su Y, Lin J, Tang K. Cordyceps fungi: natural products, pharmacological functions and developmental products. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;61(3):279–291. doi: 10.1211/jpp/61.03.0002. doi: 10.1211/jpp/61.03.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JS, Halpern GM, Jones K. The scientific rediscovery of a precious ancient Chinese herbal regimen: Cordyceps sinensis: part II. J Altern Complement Med. 1998a;4(4):429–457. doi: 10.1089/acm.1998.4.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JS, Halpern GM, Jones K. The scientific rediscovery of an ancient Chinese herbal medicine: Cordyceps sinensis: part I. J Altern Complement Med. 1998b;4(3):289–303. doi: 10.1089/acm.1998.4.3-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]