The Jarisch–Herxheimer Reaction After Antibiotic Treatment of Spirochetal Infections: A Review of Recent Cases and Our Understanding of Pathogenesis (original) (raw)

Abstract

Within 24 hours after antibiotic treatment of the spirochetal infections syphilis, Lyme disease, leptospirosis, and relapsing fever (RF), patients experience shaking chills, a rise in temperature, and intensification of skin rashes known as the Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction (JHR) with symptoms resolving a few hours later. Case reports indicate that the JHR can also include uterine contractions in pregnancy, worsening liver and renal function, acute respiratory distress syndrome, myocardial injury, hypotension, meningitis, alterations in consciousness, seizures, and strokes. Experimental evidence indicates it is caused by nonendotoxin pyrogen and spirochetal lipoproteins. Mediation of the JHR in RF by the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-8 has been proposed, consistent with measurements in patients' blood and inhibition by anti-TNF antibodies. Accelerated phagocytosis of spirochetes by polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes before rise in cytokines is responsible for removal of organisms from the blood, suggesting an early inflammatory signal from PMNs. Rarely fatal, except in neonates and in pregnancy for African women whose babies showed high perinatal mortality because of low birth weight, the JHR can be regarded as an adverse effect of antibiotics, necessary for achieving a cure of spirochetal infections.

Introduction

The Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction (JHR) was named after European dermatologists who described in 1895 and 1902 patients with syphilis who developed exacerbations of their skin lesions after treatment with mercurial compounds.1–3 After penicillin became the drug of choice for syphilis in the 1940s, the JHR occurred during the first 24 hours of treatment in primary and secondary disease as well in general paresis of the insane manifesting as fever, chills, headache, myalgias, and intensification of skin rashes.

In other spirochetal infections, including Lyme disease (LD), leptospirosis, and relapsing fever (RF), a similar reaction was reported after treatments with penicillins, tetracyclines, and erythromycin. In addition, newer antimicrobials such as cephalosporins, meropenem, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin can provoke the JHR.4–10 The purpose of this review is to update reports of the JHR in the past 25 years and to examine our understanding of its pathogenesis. Case reports were included if listed in PubMed during 1990–2015 under JHR, Treponema, Leptospira, or Borrelia. Studies of pathogenesis included older publications assembled by cross-referencing of papers about mechanisms of the JHR.

Frequency and Severity of the JHR

Syphilis.

Syphilis persists as the leading spirochetal infection that gives rise to a JHR. The common signs of JHR were fever and exacerbation of skin rashes. Frequency of JHR occurrences in syphilis and other spirochetal infections shown in Table 1 varied from 1 to 100% in observations about antimicrobial therapy,11–33 indicating large variations in patients' susceptibilities as well as varying criteria used by observers of the reaction.

Table 1.

Frequency of JHR in spirochetal infections in prospective studies, randomized trials of antimicrobial drugs, surveys, and meta-analyses

| Clinical condition | Frequency as percent of treated patients who developed a JHR | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Syphilis | ||

| Primary, secondary, and early latent treated with penicillin | ||

| RPR titer ≥ 1:32 | 41 | 11 |

| RPR titer < 1:32 | 16 | 11 |

| HIV positive | 35 | 11 |

| HIV negative | 25 | 11 |

| Penicillin | 56 | 10 |

| Azithromycin | 14 | 10 |

| Secondary syphilis treated with penicillin | 9 | 12 |

| Syphilis in pregnancy | 40–45 | 13,14 |

| Neurosyphilis | 8–75 | 15–17 |

| Lyme disease, early with erythema migrans | ||

| Azithromycin | 7 | 18 |

| Amoxicillin | 15 | 18 |

| Amoxicillin | 8 | 19 |

| Cefuroxime axetil | 8 | 19 |

| Amoxicillin | 10 | 9 |

| Clarithromycin | 11 | 9 |

| Cefuroxime axetil | 12 | 20 |

| Doxycycline | 12 | 20 |

| Cefuroxime axetil | 29 | 21 |

| Doxycycline | 8 | 21 |

| Erythromycin, penicillin, tetracycline | 14 overall, more with penicillin and tetracycline than with erythromycin | 22 |

| Azithromycin | 13 | 23 |

| Doxycycline | 12 | 23 |

| Azithromycin | 5 | 24 |

| Doxycycline | 10 | 24 |

| Azithromycin | 30 | 25 |

| Doxycycline | 30 | 25 |

| Penicillin | 19 | 25 |

| Leptospirosis | ||

| Meta-analysis of 976 cases in trials | 9, mostly treated with penicillin or ampicillin | 26 |

| Family of four persons | 50, those treated with ceftriaxone or meropenem and doxycycline | 6 |

| Penicillin | 83 | 27 |

| Relapsing fever | ||

| Tick-borne | ||

| Surveys of cases in United States and Canada | 39 | 28 |

| Surveys in Iran | 1 | 29 |

| Louse-borne | ||

| Meta-analysis of 438 patients in six randomized trials | ||

| Penicillin | 37 | 30 |

| Tetracycline | 48 | 30 |

| Erythromycin | 80 | 31 |

| Penicillin | 67 | 31 |

| Tetracycline | 96 | 31 |

| Slow-release penicillin* | 100 | 32 |

| Tetracycline* | 100 | 32 |

| Tetracycline | 47 | 33 |

| Procaine penicillin 400,000 units | 31 | 33 |

| Procaine penicillin 200,000 units | 28 | 33 |

| Procaine penicillin 100,000 units | 5 | 33 |

In a prospective study of 33 pregnant women in Texas with syphilis, who were treated with benzathine penicillin, 15 (45%) developed a JHR that was more common in primary and secondary infections than in latent infections; it started 2–8 hours after therapy, peaked at 6–12 hours, and resulted in fever and uterine contractions in most women, resulting in delivery of three infants with congenital syphilis.13 In 13 pregnant women in Chicago with syphilis who developed a JHR, uterine contractions were noted that resolved within 24 hours.14 A woman in Texas with preterm labor given penicillin for prophylaxis of Streptococcus agalactiae vaginal carriage developed chills and tachycardia, only to be found seropositive for syphilis with papulosquamous skin lesions after delivery of her baby with congenital infection.34 A woman in Japan presented in labor, received ampicillin prophylaxis for S. agalactiae and delivered 6 hours later a baby with a diffuse skin rash including blisters that suggested a JHR along with signs of congenital syphilis; after delivery, the baby received ampicillin, followed an hour later by fever and tachypnea, suggesting another JHR.35

Case reports revealed the JHR in syphilis to be multifaceted in organs affected. A characteristic patient in New York, a 45-year-old human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive man with rash, was treated with penicillin intravenously. An hour later, he developed a chill with a pulse rate of 140 and respirations of 28 per minute. This JHR was initially attributed to penicillin allergy.36 In a 45-year-old man in Ottawa with secondary syphilis as well as coinfection with HIV and hepatitis C virus, penicillin caused a JHR along with worsening liver function.37 From six case reports of neurosyphilis, additional neurological dysfunctions during the JHR occurred.15,38–42 Hallucinations or changes in consciousness or orientation were noted in three cases, seizures in three, abnormal magnetic resonance imaging or electroencephalograph in three, hemiparesis in two, and one each of facial nerve weakness and diplopia. In a Japanese man with dementia, treatment of neurosyphilis with penicillin provoked a JHR, from which he recovered, but his dementia persisted.43

Lyme disease.

In trials shown in Table 1, the range of JHR frequency was 7–30%, indicating a trend toward lower frequency than for syphilis. Furthermore, the reactions in LD were clinically milder than in the other diseases, without organ dysfunction or need for hospitalization. A severe case was a 31-year-old woman in Connecticut with a tick bite followed by erythema migrans, who received amoxicillin, which an hour later provoked chills, a temperature of 40°C, and hypotension that resolved over 3 hours while getting 3 L of intravenous saline.44

Leptospirosis.

A review of 976 cases of leptospirosis treated with antibiotics revealed detection of JHR in 92 patients, for an incidence of 9%.26 Only one of the patients died. He was a 20-year-old man in Ireland with jaundice and renal failure, who deteriorated after receiving penicillin, expiring the next day.45 Most of the cases of JHR were from one study in Malaya in 1957 that reported a JHR in 70 of 84 (83%) patients who received intramuscular penicillin injections.27

A 29-year-old woman in France, who acquired leptospirosis 10 days after falling into a river while canoeing, experienced a JHR 4 hours after receiving amoxicillin when nuchal rigidity also developed; her spinal fluid showed elevated polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells and high protein concentration.46 A 59-year-old man in Japan, 2 weeks after drinking swamp water in Okinawa, presented with fever and jaundice leading to a diagnosis of leptospirosis; 2 hours after treatment with ceftriaxone, he became more febrile with shock requiring vasopressors and intubation before recovering.4 Two hours after treatment with ceftriaxone for leptospirosis, a 49-year-old man in United Kingdom manifested a JHR with rising temperature, tachycardia, and elevation of creatinine necessitating intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring and hemodialysis before recovering.5 A 42-year-old man in Japan with leptospirosis treated with ceftriaxone developed on the next day multi-organ failure, hemoptysis, and radiographic signs of pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage with recovery 6 days later.47 Two of four family members in Switzerland after a white-water rafting trip to Thailand acquired leptospirosis and developed a JHR after treatment with ceftriaxone, meropenem, and doxycycline with serious consequences of hypotension, requiring adrenergic therapy in one case, as well as impaired liver and renal function.6 A 60-year-old farmer in Australia with fever, confusion, and thrombocytopenia developed a JHR 2 hours after receiving penicillin and ceftriaxone followed by uncomplicated recovery.48 A 51-year-old man in United Kingdom with fever, jaundice, and renal failure developed a JHR 5 hours after penicillin therapy and required hemodialysis before recovering.49 A 21-year-old man in United Kingdom after falling into a river from his canoe became febrile with vomiting and diarrhea; a JHR occurred 4 hours after penicillin treatment followed by an uneventful recovery.49

Relapsing fever.

In RF, the frequency, severity, and timing of the JHR are more predictable than in other infections. RF differs from other infections by having large numbers of organisms visible in blood plasma, convenient for rapid diagnosis in blood smears as well as following clearance of spirochetes after treatment. During the JHR, which occurs in most patients 1–2 hours after antibiotic treatment, spirochetes disappear from the blood within about 5 hours. Except in Ethiopia, where louse-borne relapsing fever (LBRF) is prevalent, all cases reported in recent years from other African countries, North America, the Middle East, and Spain are tick-borne relapsing fever (TBRF).28,29,50 An exception was two young male migrants from Eritrea in Netherlands in 2015, who had traveled through Ethiopia, had LBRF, and developed severe JHRs 2 hours after treatment, and recovered after care in the ICU.51 In the United States and Canada between 1977 and 2000, 450 patients with TBRF were recorded.28 Only one death occurred, in a neonate, whose mother was also infected. In 129 patients with clinical information about treatment available, 50 of them (39%) showed a JHR (Table 1). Most had reactions within 2 hours after treatment, consisting usually of chills, sweating, tachycardia, and hypotension without cutaneous manifestations. In one patient, the JHR started 30 minutes after an intravenous dose of doxycycline. In a meta-analysis of six studies in Ethiopia of patients with RF, a JHR occurred in 89 of 239 patients (37%) treated with penicillin and in 96 of 199 patients (48%) treated with tetracycline.30 Only four deaths were reported in each group for a case-fatality rate of 8/438, or 2%. A 59-year-old woman in the United States on steroids for thrombocytopenia with a heavy infection was treated with doxycycline and ceftriaxone.52 She did not show a JHR initially, perhaps because of steroid treatment before antibiotics, but was hospitalized 3 days later with acute respiratory distress syndrome and pulmonary edema, requiring mechanical ventilation with eventual recovery. A 75-year-old woman in United States developed a JHR 4 hours after receiving levofloxacin that was followed by chest pain and low back pain as well as a rise in troponin I before recovering.8 Two hours after intravenous doxycycline for TBRF, a 12-year-old girl in Spain developed vomiting, diminished consciousness, a blood pressure of 60/30 mmHg, and cardiac dysfunction shown by decreased ventricular ejection fraction and a rise in blood level of troponin I requiring mechanical ventilation and positive end-expiratory pressure for recovery.50 After returning from travel in Senegal, a 47-year-old Belgian woman developed RF and experienced a JHR after treatment with doxycycline.53

Among 137 pregnant women in Tanzania with treated RF, 80 went into labor with the sad result that 38 infants died (47.5%), mostly because of low birthweight; however, only 1.5% of the women were noted to have a JHR and 1.5% of the women died. In these 80 women, it was unclear whether their premature labor was caused by their RF infections mainly or by the antibiotic treatment.54 A 19-year-old woman in Tanzania with RF delivered her baby, after which she was treated with penicillin, only to die the same day during a JHR.55 Neonatal infections, likely acquired from maternal infections during birth or across the placenta before birth, are rare but often fatal. In a report of five cases of neonatal RF in Tanzania, three died within a few hours after penicillin treatment.56 Heavy spirochetemia was blamed for their deaths, but JHR cannot be excluded in case reports without information about changes in vital signs after treatment.

Pathogenesis of JHR

Inflammatory substances in spirochetes.

Clinical observations of patients with the JHR suggested a role for endotoxin,57–59 but experimental studies showed that spirochetes do not have biologically active endotoxin as defined by the limulus test.60–63 Substances other than endotoxin as well as mechanisms were described.64–71 In Treponema pallidum, lipoproteins were identified as likely responsible for inflammatory signs because they stimulate macrophages to produce tumor necrosis factor (TNF).64 In Borrelia Burgdorferi, the outer surface protein A lipoprotein stimulates cells in culture to produce transcription factors for cytokines.65 Borrelia recurrentis from human plasma was also negative for endotoxin by the limulus test but was pyrogenic in rabbits.66 The nonendotoxin pyrogen could be the same as the lipoprotein. Lipoprotein of the outer membrane proteins of leptospires caused inflammation in mouse kidney cells.67

Cytokines.

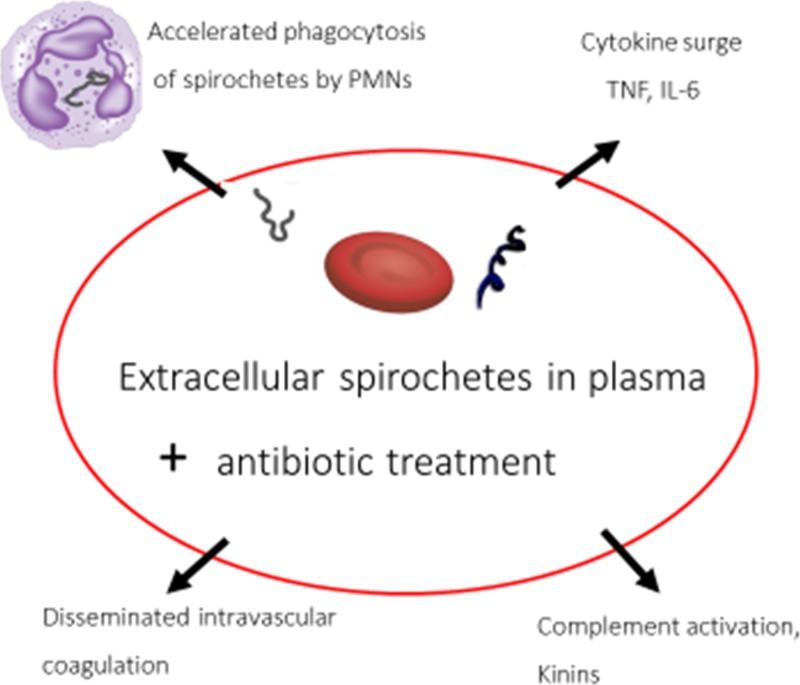

In patients with RF, plasma concentrations of the cytokines TNF, interleukin IL-6, and IL-8 were measured as sharply increasing at 2–4 hours after penicillin treatment when patients were experiencing a JHR, with a return toward baseline levels 12 hours after therapy (Figure 1).68 Anti-TNF antibodies administered before antibiotic treatment prevented or attenuated the JHR, while also reducing levels of IL-6 and IL-8 during the reactions.72,73 The cytokine response to Borrelia spirochetes requires recognition by Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) or TLR1/TLR2 heterodimers on the surfaces of phagocytes.74,75 The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was very elevated in LBRF patients, but treatment of patients with recombinant IL-10 did not prevent JHR and did not inhibit rises of TNF, IL-6, or IL-8 during the JHR.76

Figure 1.

Proposed pathogenesis of Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction in relapsing fever. PMNs = polymorphonuclear leukocytes; TNF = tumor necrosis factor; IL-6 = interleukin-6.

Phagocytosis.

At the onset of the JHR of LBRF, about 2 hours after antibiotic treatment, phagocytosis of spirochetes by blood PMNs had increased from a mean of 5% of cells that contained spirochetes before treatment to 23%, and addition of antibiotic to blood obtained before treatment caused a sharp rise in numbers of PMNs containing spirochetes during 0.5–2 hours of incubation.69 Spirochetes were demonstrated in PMNs with the Dieterle silver stain and in phagocytic vacuoles by electron microscopy.

In vitro studies of phagocytosis by monocytes showed that live, whole B. burgdorferi spirochetes stimulated ingesting monocytes to produce cytokines better than heat-killed or lysates of organisms.77 Apoptosis or programmed cell death of monocytes after phagocytosis of Borrelia could also be a factor driving the JHR.77 After phagocytosis, B. burgdorferi uses TLR2 signaling to give a pro-inflammatory cytokine response via the adapter molecule MyD88.78–80

Disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Biopsy of the petechiae was performed in patients with RF and resulted in thrombocytopenia due to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) but not vasculitis or endothelial damage.66 Conjunctival hemorrhages in a patient in Spain was also associated with thrombocytopenia.81

Complement activation, kinins, and histamine.

Serum levels of hemolytic complement and properdin were reduced in patients with RF before and after antibiotic treatment, suggesting consumption of complement in the alternative complement pathway due to phagocytosis of Borrelia.70 Other studies of RF, however, indicated that complement was not activated.32 Elevated blood levels of histamine and kinins were measured in patients with syphilis and RF before and after the JHR, suggesting roles for these mediators of inflammation.70,71

Discussion

The JHR often goes unrecognized and is underreported. Its symptoms of chills, fever, myalgia, and skin rash are often present before antibiotic treatment, so the worsening of these symptoms after antibiotic treatment can be overlooked as signs of the underlying infection. Another reason for underdiagnosis is confusing the JHR with antibiotic allergy. Physicians need to anticipate a JHR when treating spirochetal diseases to provide supportive care of monitoring vital signs and administering fluids. Clinical acumen to detect a JHR when using antibiotics for other purposes than treating spirochetal infections, like prophylaxis of S. agalactiae during pregnancy, can uncover a diagnosis of syphilis.34

Warnings about severe reactions or fatal outcomes are exaggerated and inappropriate in most situations because fatalities are rare.26,30,82 No deaths due to JHR in syphilis or LD were evident in this review. The small number of fatalities during the JHR could suggest that these patients were so severely affected by their leptospirosis or RF before treatment that they would have died without antibiotic treatment. Clinical descriptions of the JHR indicate that its definition should be broadened from chills, rising temperature, and intensification of skin rash to include sometimes meningitis, pulmonary failure, liver and renal dysfunction, myocardial injury, premature uterine contractions in pregnant patients, and worsening cerebral function as well as strokes and seizures.

In pathogenesis, not all JHRs are alike. The timing of the reaction after treatment in syphilis is to start at 4 hours, peak at 8 hours, and subside by 16 hours,1 whereas in RF it starts at 1–2 hours, peaks at 4 hours, and subsides by 8 hours. In addition, blood white cell counts in syphilis show leukocytosis and lymphopenia but show leukopenia with neutropenia in RF.32,83 Intensification of skin rashes occurs in syphilis and LD but not in leptospirosis and RF because spirochetes in syphilis and LD are plentiful in skin but localized more to blood and other body fluids in leptospirosis and RF.84

The JHR has been variously attributed by authors for more than a century to release of toxins by dying spirochetes, hypersensitivity to spirochetes, removal of dead spirochetes by phagocytic cells, complement activation, DIC, and mediators of inflammation including cytokines and histamine. However, many of these mechanisms are unsupported and probably wrong. Spirochetes of LD need 48–72 hours of exposure to antibiotics before they die,85 ruling out a rapid lethal antibiotic effect. Besides, destruction of spirochetes followed by release of toxins is not compatible with findings of intact spirochetes in phagocytic vacuoles hours after treatment.69 Although hypersensitivity reactions have been proposed,86 studies of leukocyte counts in patients as well as inconsistent results from injections of leukocytes and serum into skin of patients proved that allergic or other hypersensitivity reactions were unlikely.83 The earliest event in the JHR demonstrated to date in the JHR of RF, which is a likely trigger, is the rapid uptake of antibiotic-altered spirochetes by blood PMNs, resulting in removal of spirochetes from the blood. Before the JHR, most spirochetes in the body are in extracellular spaces of the skin or in blood plasma,84 where they usually elicit only mild or moderately severe inflammation. After antibiotic treatment, spirochetes are rendered more susceptible to PMN phagocytosis likely caused by an alteration of the microbial surface to expose antigens and molecular patterns that allow antibody and complement to bind more effectively for phagocytic uptake. Once inside, PMN spirochetes probably provoke more severe inflammation. Studies of phagocytosis of spirochetes by mononuclear cells in vitro suggest roles for mononuclear phagocytes in pathogenesis of the JHR.64,77

Causes of inflammation in the JHR are multifactorial. Spirochetal inflammatory substances include lipoproteins and nonendotoxin pyrogens that cause rises in cytokines.64–67 Studies in patients with RF indicate that in the first 2 hours after antibiotic treatment, when spirochetes are cleared from blood, rises in concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines occur.68,82 It is unlikely, however, that rising blood levels of the cytokines TNF, IL-6, and IL-8 initiate the JHR because the chill and temperature rise start as early as 30 minutes to 1 hour after antibiotic treatment,28,68,73 when blood levels of these cytokines, already elevated before antibiotic treatment, stay about the same for 30 minutes to 1 hour after treatment.68,70,82 Rises of cytokines are evident only 2–4 hours after antibiotic when the JHR is already fully expressed. Thus, the rises of cytokines appear to be the result of the JHR rather than its cause, while contributing to the intensity of the reaction as shown by the amelioration by anti-TNF antibodies.72

With the discovery that plasma cytokines rise in the JHR, it was inevitable that an analogy was drawn between the JHR and septic shock caused by other bacteria. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome of sepsis is similar in both conditions. However, the JHR is short lived over several hours, after which patients are improved, rarely die, and cytokines return to pre-JHR levels.68 Only two patients in this review, both with leptospirosis, required vasopressors for severe hypotension,4,6 whereas in septic shock the inflammatory response is more sustained with high case-fatality rates despite the use of vasopressors. Sustained shock in sepsis can be correlated with endothelial cell damage leading to failure of the microcirculation, which does not occur in JHR.66 Favorable prognosis in the JHR can be explained in part by spirochetes having a nonendotoxin pyrogen that is much less potent and less lethal than endotoxin.66

Efforts to prevent the JHR have been tried and are currently used by some physicians who give corticosteroids before penicillin in neurosyphilis or early syphilis to prevent or to blunt the severity of a JHR,41,87–89 but it is not clear whether this therapy is effective enough to be indicated.3 A possible disadvantage of corticosteroids would be inhibition of phagocytosis that is useful for clearing spirochetes during the JHR and for preventing relapses.90 Use of acetaminophen or hydrocortisone 2 hours before and 2 hours after erythromycin for RF did not prevent the JHR but ameliorated it by lessening the reduction of systolic blood pressure.31 The opioid antagonist meptazinol given with and 30 minutes after tetracycline to patients with RF in Ethiopia delayed the onset of the JHR and diminished its severity.91 Side effects, including vomiting in half the patients, would limit the usefulness of this drug. Lower frequencies of JHR with azithromycin in syphilis and LD could favor use of macrolides,10,18 but this trend was not consistent across all studies. Low doses and slow-release forms of antibiotics were tried,32,33 but are not recommended because they allowed prolonged symptoms with potential for relapses. With the demonstration that anti-TNF antibody therapy could prevent and ameliorate the JHR in RF,72 it was hopeful that an effective therapy could be applied to patient care. Another anti-cytokine drug, pentoxifylline, failed to prevent the JHR and cytokine rises in RF.92 The prognosis is so favorable for full recovery in a few hours in most patients given supportive care and adequate fluids, however, that anti-cytokine treatment is probably not justified.

Footnotes

Author's address: Thomas Butler, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Ross University School of Medicine, Portsmouth, Dominica, West Indies, E-mail: tbutler@rossu.edu.

References

- 1.Aronson IK, Soltani K. The enigma of the pathogenesis of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. Br J Vener Dis. 1976;52:313–315. doi: 10.1136/sti.52.5.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belum GR, Belum VR, Arudra SKC, Reddy BSN. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction revisited. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013;11:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pound MW, May DB. Proposed mechanisms and preventative options of Jarisch-Herxheimer reactions. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30:291–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2005.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takamizawa S, Gomi H, Shimizu Y, Isono H, Shirokawa T, Kato M. Leptospirosis and Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. QJM. 2015;108:967–968. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcv077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pimenta D, Democratis J. Risky behaviour: a rare complication of an uncommon disease in a returning traveller. BMJ Case Rep. 20132013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201075. pii:bcr-2013-201075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallardo C, Williams-Smith J, Jaton K, Asner S, Cheseaux JJ, Troillet N, Manuel O, Berthod D. Leptospirosis in a family after whitewater rafting in Thailand. Rev Med Suisse. 2015;11:872–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster G, Schiffman JD, Dosanjh AS, Amieva MR, Gans HA, Sectish TC. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction associated with ciprofloxacin administration for tick-borne relapsing fever. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:571–573. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200206000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoekstra KA, Kelly MT. Elevated troponin and Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in tick-borne relapsing fever: a case report. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2011;2011:950314. doi: 10.1155/2011/950314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nizič T, Velikanje E, Ružić-Sabljić E, Arnež M. Solitary erythema migrans in children: comparison of treatment with clarithromycin and amoxicillin. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:427–433. doi: 10.1007/s00508-012-0194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai M-S, Yang C-J, Lee N-Y, Hsieh S-M, Lin Y-H, Sun H-Y, Sheng W-H, Lee K-Y, Yang S-P, Liu W-C, Wu P-Y, Ko W-C, Hung C-C. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction among HIV positive patients with early syphilis: azithromycin versus benzathine penicillin G therapy. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18993. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang C-J, Lee N-Y, Lin Y-H, Lee H-C, Ko W-C, Liao C-H, Wu C-H, Hsieh C-Y, Wu P-Y, Liu W-C, Chang Y-C, Hung C-C. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction after penicillin therapy among patients with syphilis in the era of the HIV infection epidemic: incidence and risk factors. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:976–979. doi: 10.1086/656419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller WM, Gorini F, Botelho G, Moreira C, Barbosa AP, Pinto ARSB, Dias MF, Sousa LM, Asensi MD, da Costa Nery JA. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction among syphilis patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21:806–809. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein VR, Cox SM, Mitchell MD, Wendel GD. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction complicating syphilotherapy in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:375–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myles TD, Elam G, Park-Hwang E, Nguyen T. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction and fetal monitoring changes in pregnant women treated for syphilis. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:859–864. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silberstein P, Lawrence R, Pryor D, Shnier R. A case of neurosyphilis with florid Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:689–690. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2002.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis LE, Oyer R, Beckham JD, Tyler KL. Elevated CSF cytokines in the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction of general paresis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1060–1064. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Punia V, Rayi A, Sivaraju A. Stroke after initiating IV penicillin for neurosyphilis: a possible Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. Case Rep Neuro Med. 2014;2014:548179. doi: 10.1155/2014/548179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnež M, Ružić-Sabljić E. Azithromycin is equally effective as amoxicillin in children with solitary erythema migrans. Pediatr Infect Dis. 2015;34:1045–1048. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eppes SC, Childs JA. Comparative study of cefuroxime axetil versus amoxicillin in children with early lyme disease. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1173–1177. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luger SW, Paparone P, Wormser GP, Nadelman RB, Grunwald E, Gomez G, Wisniewski M, Collins JJ. Comparison of cefuroxime axetil and doxycycline in treatment of patients with early lyme disease associated with erythema migrans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:661–667. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nadelman RB, Luger SW, Frank E, Wisniewski M, Collins JJ, Wormser GP. Comparison of cefuroxime axetil and doxycycline in the treatment of early lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:273–280. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-4-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steere AC, Hutchinson GJ, Rahn DW, Sigal LH, Craft JE, DeSanna ET, Malawista SE. Treatment of the early manifestations of lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:22–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strle F, Preac-Mursic V, Cimperman J, Ružić E, Maraspin V, Jereb M. Azithromycin versus doxycycline for treatment of erythema migrans: clinical and microbiological findings. Infection. 1993;21:83–88. doi: 10.1007/BF01710737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strle F, Maraspin V, Lotric-Furlan S, Ružić-Sabljić E, Cimperman J. Azithromycin and doxycycline for treatment of Borrelia culture-positive erythema migrans. Infection. 1996;24:66–70. doi: 10.1007/BF01780661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strle F, Ružić E, Cimperman J. Erythema migrans: comparison of treatment with azithromycin, doxycycline and phenoxymethylpenicillin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;30:543–550. doi: 10.1093/jac/30.4.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerrier G, D'Ortenzio E. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in leptospirosis: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacKay-Dick J, Robinson JF. Penicillin in the treatment of 84 cases of leptospirosis in Malaya. J R Army Med Corps. 1957;103:186–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dworkin MS, Shoemaker PC, Fritz CL, Dowell ME, Anderson DE. The epidemiology of tick-borne relapsing fever in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:753–758. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asi HM, Goya MM, Vatandoost H, Zahraei SM, Mafi M, Asmar M, Piazak N, Aghighi Z. The epidemiology of tick-borne relapsing fever in Iran during 1997–2006. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009;7:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guerrier G, Doherty T. Comparison of antibiotic regimens for treating louse-borne relapsing fever: a meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butler T, Jones PK, Wallace CK. Borrelia recurrentis infection: single-dose antibiotic regimens and management of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. J Infect Dis. 1978;137:573–577. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.5.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warrell DA, Perine PL, Krause DW, Bing DH, MacDougal SJ. Pathophysiology and immunology of the Jarisch-Herxheimer-like reaction in louse-borne relapsing fever: comparison of tetracycline and slow-release penicillin. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:898–909. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.5.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seboxa T, Rahlenbeck SI. Treatment of louse-borne relapsing fever with low dose penicillin or tetracycline: a clinical trial. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;27:29–31. doi: 10.3109/00365549509018969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rac MWF, Greer LG, Wendel GD. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction triggered by group B Streptococcus intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:552–556. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e7d065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hori H, Sato Y, Shitara T. Congenital syphilis presenting as Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction at birth. Pediatr Int. 2015;57:299–301. doi: 10.1111/ped.12417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.See S, Scott EK, Levin MW. Penicillin-induced Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:2128–2130. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooper C, MacPherson P, Angel JB. Liver toxicity resulting from syphilis and Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in cases of co-infection with HIV and hepatitis C virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1211–1212. doi: 10.1086/428848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berger EM, Galadari HI, Gottlieb AB. Case reports: unilateral facial paralysis after treatment of secondary syphilis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:583–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bucher JB, Golden MR, Heald AE, Marra CM. Stroke in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis treated with penicillin and antiretroviral therapy. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:442–444. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181ffa5d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kojan S, Van Ness PC, Diaz-Arrastia R. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus resulting from Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in a patient with neurosyphilis. Clin Electroencephalogr. 2000;31:138–140. doi: 10.1177/155005940003100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zifko U, Lindner K, Wimberger D, Volc B, Grisold W. Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in a patient with neurosyphilis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:865–867. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.7.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang S-Q, Wan B, Ma X-L, Zheng H-M. Worsened MRI findings during the early period of treatment with penicillin in a patient with general paresis. J Neuroimaging. 2008;18:360–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2007.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hagiya H, Deguchi K, Kawada K, Otsuka F. Neurosyphilis is a long-forgotten disease but still a possible etiology for dementia. Intern Med. 2015;54:2769–2773. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maloy AL, Black RD, Segurola RJ. Lyme disease complicated by the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:437–438. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(98)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaughn C, Cronin CC, Walsh EK, Whelton M. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in leptospirosis. Postgrad Med J. 1994;70:118–121. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.70.820.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tattevin P, Jaureguiberry S, Michelet C. Meningitis as a possible feature of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:449. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-0957-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hashimoto T, Akata S, Park J, Harada Y, Hirayama Y, Otaki J, Tokuuye K. High-resolution computed tomography findings in a case of severe leptospira infection (Weil disease) complicated with Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. J Thorac Imaging. 2012;27:W24–W26. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e318231535b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Markham R, Slack A, Gerrard J. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in a patient with leptospirosis: a foreseeable problem in managing spirochaete infections. Med J Aust. 2012;197:276–277. doi: 10.5694/mja11.11175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedland JS, Warrell DA. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in leptospirosis: possible pathogenesis and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:207–210. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garcia-Soler P, Nunez-Cuadros E, Milano-Manso G, Sanchez PR. Severe Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in tick-borne relapsing fever. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2011;29:710–711. doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilting KR, Stienstra Y, Sinha B, Braks M, Cornish D, Grundmann H. Louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis) in asylum seekers from Eritrea, The Netherlands, July 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.30.21196. 20.30.21196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Badger MS. Tick talk: unusually severe case of tick-borne relapsing fever with acute respiratory distress syndrome—case report and review of literature. Wild Env Med J. 2008;19:280–286. doi: 10.1580/07-WEME-CR-140.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Colebunders R, De Serrano P, Van Gompel A, Wynants H, Blot K, Van Den Enden E, Van Den Ende J. Imported relapsing fever in European tourists. Scand J Infect Dis. 1993;25:533–536. doi: 10.3109/00365549309008539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jongen VHWM, van Roosmalen J, Tiems J, Holten JV, Wetsteyn JCFM. Tick-borne relapsing fever and pregnancy outcome in rural Tanzania. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:834–838. doi: 10.3109/00016349709024361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rustenhoven-Spaan I, Melkert P, Nelissen E, van Roosmalen J. Maternal mortality in a rural Tanzanian hospital: fatal Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in a case of relapsing fever in pregnancy. Trop Doct. 2013;43:138–141. doi: 10.1177/0049475513497477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Melkert PWJ, Stel HV. Neonatal Borrelia infections (relapsing fever): report of 5 cases and review of the literature. East Afr Med J. 1991;68:999–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bryceson ADM, Cooper KE, Warrell DA, Perine PL, Parry EHO. Studies of the mechanism of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in louse-borne relapsing fever: evidence for the presence of circulating Borrelia endotoxin. Clin Sci. 1972;43:343–354. doi: 10.1042/cs0430343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bryceson ADM. Clinical pathology of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. J Infect Dis. 1976;133:696–704. doi: 10.1093/infdis/133.6.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gelfand JA, Elin RJ, Berry FW, Frank MM. Endotoxemia associated with the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:211–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197607222950409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takayama K, Rothenberg RJ, Barbour AG. Absence of lipopolysaccharide in the lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2311–2313. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2311-2313.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Young EJ, Weingarten NM, Baughn RE, Duncan WC. Studies on the pathogenesis of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction: development of an animal model and evidence against a role for classical endotoxin. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:606–615. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.5.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shenep JL, Feldman S, Thornton D. Evaluation for endotoxemia in patients receiving penicillin therapy for secondary syphilis. JAMA. 1986;256:388–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hardy PH, Levin J. Lack of endotoxin in Borrelia hispanica and Treponema pallidum. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1983;174:47–52. doi: 10.3181/00379727-174-41702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Akins DR, Purcell BK, Mitra MM, Norgard MV, Radolf JD. Lipid modification of the 17-kilodalton membrane immunogen of Treponema pallidum determines macrophage activation as well as amphiphilicity. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1202–1210. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1202-1210.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bulut Y, Faure E, Thomas L, Equils O, Arditi M. Cooperation of Toll-like receptor 2 and 6 for cellular activation by soluble tuberculosis factor and Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein A lipoprotein: role of toll-interacting protein and IL-1 receptor signaling molecules in Toll-like receptor 2 signaling. J Immunol. 2001;167:987–994. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Butler T, Hazen P, Wallace CK, Awoke S, Habte-Michael A. Borrelia recurrentis infection: pathogenesis of fever and petechiae. J Infect Dis. 1979;140:665–675. doi: 10.1093/infdis/140.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang C-W, Hung C-C, Wu M-S, Tian Y-C, Chang C-T, Pan M-J, Vandewalle A. Toll-like receptor 2 mediates early inflammation by leptospiral outer membrane proteins in proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int. 2006;69:815–822. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Negussie Y, Remick DG, DeForge LE, Kunkel SL, Eynon A, Griffin GE. Detection of plasma tumor necrosis factor, interleukins 6, and 8 during the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction of relapsing fever. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1207–1212. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Butler T, Aikawa M, Habte-Michael A, Wallace CK. Phagocytosis of Borrelia recurrentis by polymorphonuclear leukocytes is enhanced by antibiotic treatment. Infect Immun. 1980;28:1009–1013. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.3.1009-1013.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Galloway RE, Levin J, Butler T, Naff GB, Goldsmith GH, Saito H, Awoke S, Wallace CK. Activation of protein mediators on inflammation and evidence for endotoxemia in Borrelia recurrentis infection. Am J Med. 1977;63:933–938. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Loveday C, Bingham JS. Changes in intravascular complement, kininogen, and histamine during Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in secondary syphilis. Genitourin Med. 1985;61:27–32. doi: 10.1136/sti.61.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fekade D, Knox K, Hussein K, Melka A, Lalloo DG, Coxon RE, Warrell DA. Prevention of Jarisch-Herxheimer reactions by treatment with antibodies against tumor necrosis factor α. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:311–315. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608013350503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coxon RE, Fekade D, Knox K, Hussein K, Melka A, Daniel A, Griffin GG, Warrell DA. The effect of antibody against TNF alpha on cytokine response in Jarisch-Herxheimer reactions of louse-borne relapsing fever. QJM. 1997;90:213–221. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/90.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wooten RM, Ma Y, Yoder RA, Brown JP, Weis JH, Zachary JF, Kirschning CJ, Weis JJ. Toll-like receptor 2 is required for innate, but not acquired, host defense to Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol. 2002;168:348–355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oosting M, ter Hofstede H, Sturm P, Adema GJ, Kulberg B-J, van der Meer JWM, Netea MG, Joosten LAB. TLR1/TLR2 heterodimers play an important role in the recognition of Borrelia spirochetes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cooper PJ, Fekade D, Remick DG, Grint P, Wherry J, Griffin GE. Recombinant human interleukin-10 fails to alter proinflammatory production or physiogic changes associated with the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:203–209. doi: 10.1086/315183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cruz AR, Moore MW, La Vake CJ, Eggers CH, Salazar JC, Radolf JD. Phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi, the lyme disease spirochete, potentiates innate immune activation and induces apoptosis in human monocytes. Infect Immun. 2008;76:56–70. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01039-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petnicki-Ocwieja T, Chung E, Acosta DI, Ramos LT, Shin OS, Ghosh S, Kobzik L, Li X, Hu LT. TRIF mediates Toll-like receptor 2-dependent inflammatory responses to Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2013;81:402–410. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00890-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shin OS, Isberg RR, Akira S, Uematsu S, Behera AK, Hu LT. Distinct roles for MyD88 and toll-like receptors 2,5,and 9 in phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi and cytokine induction. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2341–2351. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01600-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dennis VA, Dixit S, O'Brien SM, Alvarez X, Pahar B, Philipp MT. Live Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes elicit inflammatory mediators from human monocytes via the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1238–1245. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01078-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Castilla-Guerra L, Alvarez-Suero J, Fernandez-Moreno MDC, Fontana ER. Tick-borne relapsing fever: conjunctival haemorrhages. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0114. pii:bcro6.2008.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cuevas LE, Borgnolo G, Hailu B, Smith G, Almaviva M, Hart CA. Tumour necrosis factor, interleukin-6, and C-reactive protein in patients with louse-borne relapsing fever in Ethiopia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1995;89:49–54. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1995.11812928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Skog E, Gudjonsson H. On the allergic origin of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. Acta Derm Venereol. 1966;46:136–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Koning J, Hoogkamp-Korstanje JAA. Diagnosis of lyme disease by demonstration of spirochetes in tissue biopsies. Zbl Bakt Hyg A. 1986;263:179–188. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(86)80121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Luft BJ, Gorevic PD, Halperin JJ, Volkman DJ, Dattwyler RJ. A perspective on the treatment of lyme borreliosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11((Suppl 6)):S1518–S1525. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_6.s1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kadam P, Gregory NA, Zelger B, Carlson JA. Delayed onset of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction in doxycycline-treated disease: a case report and review of its histopathology and implications for pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:e68–e74. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Luger A, Pavlik F. Der einfluss von korticosteroiden auf die Jarisch-Herxheimer-reacktion. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1971;83:208–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Muller G. Suppression of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction by means of prednisolone. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1983;169:232–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gudjonsson H, Skog E. The effect of prednisolone on the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. Acta Derm Venereol. 1968;48:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sheldon WH, Heyman A. Morphologic changes in syphilitic lesions during the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. Amer J Syphilis. 1949;33:213–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Teklu B, Habte-Michael A, Warrell DA, White NJ, Wright DJM. Meptazinol diminishes the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction of relapsing fever. Lancet. 1983;1:835–839. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Remick DG, Negussie Y, Fekade D, Griffin G. Pentoxifylline fails to prevent the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction or associated cytokine release. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:627–630. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]