Depression in Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease: Similarities and Differences in Diagnosis, Epidemiology, and Management (original) (raw)

Abstract

Depression is highly prevalent and is associated with poor quality of life and increased mortality among adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD), including those with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). However, there are several important differences in the diagnosis, epidemiology, and management of depression between patients with non−dialysis-dependent CKD and ESRD. Understanding these differences may lead to a better understanding of depression in these 2 distinct populations. First, diagnosing depression using self-reported questionnaires may be less accurate in patients with ESRD compared with CKD. Second, although the prevalence of interview-based depression is approximately 20% in both groups, the risk factors for depression may vary. Third, potential mechanisms of depression might also differ in CKD versus ESRD. Finally, considerations regarding the type and dose of antidepressant medications vary between CKD and ESRD. Future studies should further examine the mechanisms of depression in both groups, and test interventions to prevent and treat depression in these populations.

Keywords: depression, diagnosis, epidemiology, kidney disease, outcomes, treatment

Depression is well known to affect adults with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), in part attributed to psychosocial and biologic changes that accompany dialysis.1, 2 Recent studies have shown that patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who are not on dialysis have rates of depression up to 3 times higher than those in the general population.3 Furthermore, depression has been associated with poor quality of life and adverse medical outcomes in patients with CKD or ESRD.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 In this narrative Review, we will examine existing data and explore the similarities and differences in the diagnosis, epidemiology, and management of depression in patients with CKD and those with ESRD treated with maintenance dialysis (renal transplant recipients and patients who chose conservative management over dialysis or transplantation were excluded from this Review). In addition, we will suggest areas for future research aimed at furthering our understanding of the causal pathways of depression in CKD and ESRD, and evaluating interventions to prevent and/or treat depression in these populations.

Diagnosis

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), published by the American Psychiatric Association, is the standard set of criteria used to diagnose mental disorders in the United States.9 The majority of studies examining the prevalence of unipolar depression (without mania or psychosis) in CKD and ESRD through clinical interview have used the DSM to define depressive disorders.3 These studies have often used a broad definition of depression that encompasses several different depressive disorders from the DSM, including persistent depressive disorder (PDD), depressive disorder not otherwise specified (NOS), and major depressive disorder (MDD). These depressive disorders are briefly defined in Table 1.

Table 1.

DSM-V classification of depressive disorders9

| - Major depressive disorder (MDD): a clinical syndrome lasting at least 2 weeks, where patients experience either depressed mood or anhedonia, and at least 4 other symptoms of depression.a Symptoms need to cause significant distress and impairment in one’s life, and cannot be caused by substance abuse or another psychological or medical condition including mania. |

|---|

| - Persistent depressive disorder (PDD): depressed mood that occurs most days for at least 2 years, and the presence of at least 2 of the following 6 symptoms: change in appetite, insomnia or hypersomnia, fatigue, low energy, poor concentration or difficulty making decisions, and feelings of hopelessness. These symptoms may not be caused by substance abuse or a general medical condition, and must cause significant distress or impairment in one’s life. Previously known as dysthymia. |

| - Depressive disorder NOS: any depressive disorder that does not meet criteria for a specific depressive disorder like PDD or MDD. Depressive disorder NOS was previously broken up into distinct depressive disorders including minor depressive disorder. |

| - Minor depression: no longer a diagnostic classification and now classified as depressive disorder NOS in DSM-V. Previously defined as a clinical syndrome of depressed mood that lasted at least 2 weeks with at least 2 but fewer than 5 of the symptoms required to diagnose MDD |

The gold standard to diagnose depression is the clinical interview, including the following: (1) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID)10; (2) the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)11; and (3) the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).12 However, self-reported questionnaires are often used in clinical and research settings for screening of depressive symptoms. The most commonly used depression screening questionnaires that have been validated for use in patients with CKD and ESRD are as follows: Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)13; Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)13, 14; Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD)14; and Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (QIDS-SR).15

Several studies have validated depression-screening questionnaires in patients with ESRD.13, 14, 16 In a study of 98 patients with ESRD on hemodialysis by Hedayati et al., the BDI and CESD scales were validated against the SCID for diagnosing a depressive disorder (MDD, dysthymia, or minor depression).14 A BDI cutoff of 14 had a sensitivity of 62% and a specificity of 81% for identifying a depressive disorder. The corresponding sensitivity and specificity for a CESD cutoff of 18 were 69% and 83%, respectively. Both cutoff scores were higher than cutoffs set for the general population (10 for the BDI and 16 for the CESD). In a similar study by Watnick et al., the BDI and PHQ-9 were validated against the SCID for the diagnosis of a depressive disorder (MDD, dysthymia or minor depression).13 A BDI score of 16 and a PHQ-9 cutoff of 10 had sensitivity of 91% and 92%, respectively, and specificity of 86% and 92%, respectively. As in the study by Hedayati et al., the most accurate cutoff score for diagnosing a depressive disorder using the BDI was higher than in the general population. This was attributed to the overlap between somatic symptoms of depression and symptoms related to ESRD, including anemia, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, difficulty sleeping, and poor appetite. Thus, patients with uremic symptoms may screen positive for depression with a self-reported questionnaire. However, these uremic symptoms can be distinguished from depressive symptoms during a clinical interview. For this reason, the clinical interview remains the gold standard for diagnosing depression in patients with ESRD.

Only 1 study has validated questionnaires to screen for depression in patients with CKD.15 In this study of 272 patients with stage 2 to 5 CKD, Hedayati et al. validated the BDI, and QIDS-SR(16) against the MINI.15 The authors found that the optimal cutoffs for diagnosing a major depressive episode using the BDI and QIDS-SR(16) were the same as the general population, ≥11 and ≥10, respectively. However, the inclusion of patients with CKD stages 2 and 3, who are less likely to experience symptoms related to kidney disease, could have influenced the results. Future studies to validate depression-screening questionnaires in patients with advanced CKD (stages 4 and 5) for depressive disorders are needed.

Screening Strategies

Two potential strategies for screening depression in patients with CKD and ESRD are generally used.17, 18 The first, a conservative approach, is to screen only patients with signs of depression. These signs may include social isolation (withdrawal from family, friends, and social gatherings), changes in mood or physical functioning, and/or increasing physical complaints (sleep disturbance, decreased self-care, including poorer compliance with medical follow-up and dialysis). The second, a more aggressive strategy, is to screen all new CKD or ESRD patients periodically (every 6 months to 1 year) for depression with screening questionnaires (either the PHQ-9 or BDI).

Specific health care providers, namely, a nurse, social worker or physician, should be trained on a protocol for administering depression screening questionnaires, including how to appropriately triage patients. Questionnaires, particularly items evaluating suicidal ideation, should be reviewed prior to patients leaving the clinic or dialysis center. Patients who screen positive for depression should be referred to a qualified professional to confirm the diagnosis with a clinical interview. Patients who require immediate referral to a mental health professional or emergency psychiatric services include those with suicidal ideation, plan, or intent and those with depression complicated by psychosis or mania.18

Epidemiology

Prevalence of Depression in CKD and ESRD

Depression is highly prevalent in patients with CKD and ESRD. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Palmer et al. examined the prevalence of depression in these populations.3 The authors identified 216 studies of 55,982 patients with CKD or ESRD. Among patients with ESRD receiving dialysis, the summary prevalence of depression was 39.3% when evaluated by screening questionnaires, and 22.8% when evaluated by clinical interview. In patients with CKD, the summary prevalence of depression was 26.5% when evaluated by screening questionnaires, and 21.4% when evaluated by clinical interview. Prevalence rates were higher in ESRD than in CKD when questionnaires were used to diagnose depression (39.3% vs. 26.5%), but were similar when depression was diagnosed by clinical interview (22.8% vs. 21.4%). This difference is likely related to uremic symptoms (fatigue, insomnia, poor appetite) in ESRD populations that could overlap with somatic symptoms of depression when measured using questionnaires.18 Since the publication of this meta-analysis, several studies evaluating the prevalence of depressive symptoms in CKD using screening questionnaires have been published (Table 2).4, 5, 6, 7, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The largest study to date, by Fischer et al., reported a prevalence of depressive symptoms of 27.4% using a BDI cutoff of 11 among 3853 individuals with mild-to-moderate CKD enrolled in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) and Hispanic CRIC (HCRIC) studies.20

Table 2.

Recent studies evaluating prevalence and outcomes of depression in CKD

| First author, year, ref | Sample characteristics | Measurement tool for depression | Depression prevalence | Follow-up | Outcomes of depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedayati, 201022 | 267 Patients with stage 2–5 CKD | DSM-IV interview(MDE diagnosis) | 21% | 1 yr | -Composite of death, hospitalization, or ESRD: HR = 1.86 -Hospitalization: HR = 1.90 -ESRD: HR 3.51 |

| Fischer, 20117 | 628 Patients with stage 2–4 CKD | BDI-II score > 14 or ≥11 | 26 or 42% | 5 yr | -Composite of CV death or hospitalization |

| Kop, 201119 | 5785 Patients, average GFR 78 | CES-D ≥ 8 | 21.2% | 14 yr | -AKI |

| Cukor, 20124 | 70 Patients with stage 1–4 CKD | BDI-II score ≥14 | 30% | 6 mo | -Worse QOL, social support, community integration -Greater decline in GFR |

| Fischer, 201220 | 3853 Patients with stage 2–4 CKD | BDI-II score ≥ 11 | 27.4% | None | |

| Tsai, 20126 | 428 Patients with stage 3–5 CKD | BDI-II score ≥ 11 | 37% | 4 yr | -Composite of ESRD or death: HR = 1.66 -First hospitalization: HR = 1.59 -Faster GFR decline -Initial dialysis at a higher GFR |

| Lee, 20135 | 208 Patients with stage 3–5 CKD | HADS-D ≥ 8 | 47.1% | None | -Worse QOL |

| Chiang, 201523 | 262 Patients (60.3% stage 4 and above) | Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire | 21% | 3 yr | -Composite of dialysis or death: HR = 2.95 -ESRD: HR = 2.25 -Mortality: HR 3.08 |

Prevalence of Depression in Minorities

People who belong to a minority racial/ethnic group (e.g., black, Hispanic) have been shown to have higher incident rates of CKD and ESRD compared with non-Hispanic white individuals.24, 25 Unfortunately, few studies have evaluated the prevalence of depressive symptoms in minority patients with CKD or ESRD.7, 19, 20, 26, 27, 28 In their analysis of 1600 black and 490 Hispanic patients from the CRIC and HCRIC studies, Fischer et al. found that Hispanics had a 1.65 times higher odds of depression, and that blacks had a 1.43 times higher odds of depression compared with non-Hispanic white participants.20 Furthermore, both black and Hispanic individuals were significantly less likely to use antidepressant medications compared with non-Hispanic whites. Similarly, an analysis of 628 black individuals with CKD and HTN from the African-American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) cohort found a 42% depression prevalence, much higher than that observed in other mixed race/ethnicity CKD populations.3, 7 A higher risk of depression has been seen in other studies examining minorities with CKD19 but has not been seen in ESRD populations. Studies of patients with ESRD examining the effects of race/ethnicity have yielded conflicting results, either showing higher rates of depression among whites or revealing no effect of race/ethnicity on depression.26, 29 In an analysis of 5256 persons with ESRD on hemodialysis from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS), black participants were significantly less likely than white participants to have physician-diagnosed depression.26 Epidemiology and clinical studies thus far have revealed differing effects of race/ethnicity on depression in patients with CKD versus ESRD. Further studies examining this unexpected finding, especially studies examining the effects of race/ethnicity on depression in patients with ESRD, are needed.

Comparison to Other Populations

The prevalence of depression is 3 to 4 times higher in patients with CKD and ESRD compared with the general population and 2 to 3 times higher compared to individuals with other chronic illnesses. In the general population, the lifetime risk of depression is estimated to be between 5% and 10%.30, 31, 32 Rates of depression with a comorbid medical illness are even higher. For patients with diabetes, prevalence rates are between 12% and 18%; for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), rates are between 15% and 23%, and for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the estimated prevalence of depression is around 25%.32, 33

Depression and Outcomes

End-Stage Renal Disease

The majority of studies in patients with ESRD have reported an association between depression and poor psychosocial and medical outcomes, with only a minority reporting no association. In a recent systematic review, Farrokhi et al. identified 31 studies of 67,075 patients examining the association between depression and mortality in patients with ESRD receiving long-term dialysis.34 Eighteen studies were limited to hemodialysis patients; 4 included only peritoneal dialysis patients; and 9 included both modalities. The authors found that the mortality risk in patients on dialysis was 1.5 times higher in the presence of depressive symptoms independent of other confounding factors. They also found that this relationship was dose dependent, that is, the more severe the depression, the higher the risk of mortality.

A study by Hedayati et al., which was not included in the systematic review because it reported a composite outcome, is the only study that evaluated the association of depression diagnosed by a clinical interview and clinical outcomes in patients with ESRD.35 In this study, 98 patients with ESRD undergoing chronic hemodialysis underwent a SCID, and 26 were classified as depressed (MDD, dysthymia, or minor depression). Patients were followed up for 1 year, and 52 reached the primary outcome (a composite of death or first hospitalization). The adjusted hazard ratio for the primary outcome was 2.07 in patients with depression.

In addition to mortality, depression in patients with ESRD has been significantly associated with other adverse medical outcomes, including emergency department visits,28 hospitalizations,28, 36 cumulative hospital days,36 cardiovascular events,37 peritonitis,38 and withdrawal from dialysis and suicide.39 In an evaluation of 162 patients on peritoneal dialysis assessed with BDI at 6-month intervals, Troidle et al. found that a BDI score ≥11 was significantly associated with Gram-positive peritonitis.38 Moreover, in an analysis of data from the US Renal Data System (USRDS), Kurella et al. reported that suicide rates among patients with ESRD on long-term dialysis were significantly higher compared with those in the general population, and hospitalization due to a mental illness in the preceding 12 months was significantly associated with withdrawal from dialysis and suicide.39

Depression has also been associated with poor psychosocial outcomes in patients with ESRD. In a study of the AASK cohort, higher depressive symptoms were independently and significantly associated with lower quality of life.27 Furthermore, depressive symptoms have been significantly associated with fatigue,40 pain,41 pruritus,42 sleep disturbances,43, 44 and sexual dysfunction.45

Chronic Kidney Disease

Recent studies of patients with CKD who are not on dialysis have reported an association between depression and adverse medical outcomes, including hospitalization,22 acute kidney injury,19 kidney function decline,6 ESRD,23 and mortality.6, 7, 22, 23 These studies are summarized in Table 2. Hedayati et al. performed 1 of the most rigorous studies of medical outcomes in patients with major depression and CKD.22 In this study, 267 consecutively recruited patients with stage 2 to 5 CKD underwent a MINI interview, and 56 had a current major depressive episode. All participants were followed up for 1 year to monitor for the development of the composite primary outcome (death, dialysis, or hospitalization). At the end of 1 year, the adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval [CI]) for the primary outcome was 1.86 (1.23–2.84) in patients with a major depressive episode. In another prospective study of 628 AASK cohort participants with CKD (42% with elevated depressive symptoms), baseline, time-varying, and cumulative elevated depressive symptoms were significantly associated with the composite outcome of cardiovascular death or cardiovascular hospitalization, but not with a composite kidney outcome or all-cause mortality.7

Studies have reported an association of depression with kidney function decline.6, 9 A prospective study by Tsai et al. evaluated the effect of depressive symptoms on renal outcomes in 568 patients with CKD,6 of whom 160 had depressive symptoms (BDI ≥ 11). Over a mean follow-up of 2 years, individuals with depressive symptoms were 1.7 times more likely to experience the primary outcome (progression to ESRD or death) compared with those without depressive symptoms. In addition, the presence of depressive symptoms was associated with a faster rate of decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate.

A few recent studies have found an association between CKD and adverse psychosocial outcomes including quality of life,4, 5, 46, 47 poor social support,4 and sexual dysfunction.45 In a study by Cukor et al. of 70 patients with CKD, including 21 patients with depressive symptoms (BDI ≥14),4 patients with depression had significantly less integration into the community, less social support, and lower quality of life than patients without depression.4 More studies of the effects of mild-to-moderate CKD on psychosocial outcomes are needed at this time.

Etiology of Depression In CKD and ESRD

Potential explanations for the high burden of depression observed in patients with CKD and ESRD can be divided into those related to primary (unrelated to medical illness), and secondary (related to medical illness) forms of depression. The underlying mechanisms of primary depression in patients with kidney disease are beyond the scope of this Review, and are probably similar to those described in the general population.48 Unfortunately, few studies have directly examined the mechanisms of secondary depression in patients with CKD and ESRD. However, potential mechanisms can be gleaned from studies examining risk factors for depression in these populations, and from studies examining mechanisms of depression in other chronic illnesses.

Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Clinical Risk Factors for Depression

In patients with ESRD, factors that have been associated with depression include younger age, female gender, white race, longer duration of dialysis, and comorbid conditions such as diabetes, CAD, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease.36, 49 In patients with CKD, similar risk factors are associated with depression, including younger age, female gender, black race, Hispanic ethnicity, lower education, lower family income, unemployment, hypertension, smoking status, diabetes, and CAD.6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 50 In the general population, lower socioeconomic status and comorbid conditions have also been associated with higher prevalence of depression51; however, because these risk factors occur more frequently in patients with kidney disease compared with the general population, it is likely that they in part explain the higher prevalence of depression seen in patients with kidney disease compared with the general population.52, 53

Mechanisms of Depression

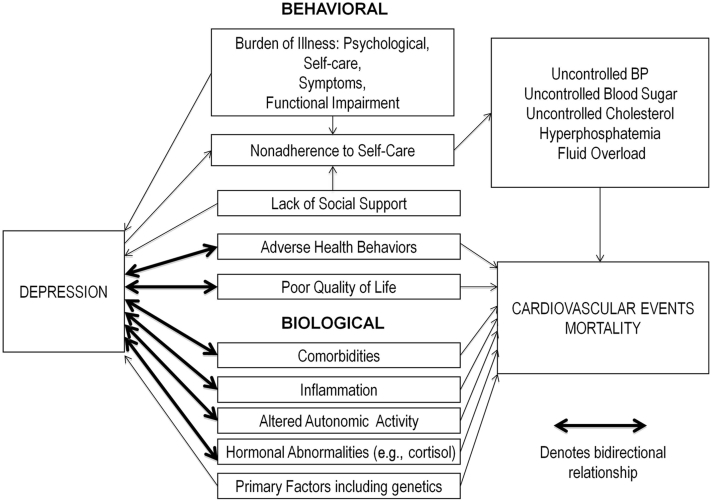

In patients with diabetes and CAD, a bidirectional association with depression has been found.32 For example, depressive symptoms have been associated with incident diabetes, and patients with clinically identified diabetes have higher odds of developing depressive symptoms than patients without diabetes.54 The directionality of the relationship between depressive symptoms and CKD is unknown but is likely bidirectional as well. Prior reviews suggest that several of the underlying mechanisms of depression in CKD are similar to those seen in other chronic illnesses and can be divided into behavioral and biological mechanisms.17, 32, 55 Figure 1 depicts behavioral and biological mechanisms explaining the association between depression and CKD and between depression and adverse outcomes in this population.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of depression and adverse medical outcomes.

Behavioral

The increased burden of self-care related to CKD and ESRD, including frequent clinic and hospital visits, dietary restrictions, increased pill burden, and home monitoring of glucose, blood pressure, and weight, may lead to depression.48, 56 This is added to the challenges associated with dialysis, such as traveling to the dialysis clinic 3 times weekly for hemodialysis, or performing daily home hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. These challenges can be particularly overwhelming for adults for whom dialysis has recently been initiated. In an analysis of 160 incident dialysis patients, depressive symptoms soon after dialysis initiation were independently associated with mortality.57

Functional impairment,46 and physical symptoms caused by chronic illness, may also contribute to the development of depression.48 For patients with CKD and ESRD, comorbid conditions such as dementia, prior stroke, or heart failure can limit daily activities. For patients with ESRD, orthostasis, headache, and fatigue after hemodialysis can prevent patients from performing routine tasks. As described above, physical symptoms related to uremia, dialysis treatment, and/or medications (e.g., gastrointestinal distress from phosphate binders) are frequently experienced by these patients, and have been associated with depression. It remains unclear whether these symptoms cause depression or whether depression causes somatic symptoms.

In patients with both CKD and ESRD, the psychological burden of having an illness that affects future morbidity and mortality may lead to depression. This may be even more relevant for patients with CKD who have to cope with thoughts of impending dialysis or transplantation.32, 58

Depression may contribute to the development of CKD through higher rates of adverse health risk behaviors such as smoking, sedentarism, and obesity.32 These behaviors are common in patients with CKD, and may worsen pre-existing diabetes, hypertension, or CAD, leading to CKD or CKD progression.59, 60, 61, 62 Interestingly, there appears to be a protective association of alcohol consumption, which is highly prevalent among patients with depression,63 with the risk of developing CKD.64

Finally, patients with ESRD have been shown to withdraw from family and social support and to have economic difficulties,52 both of which have been associated with depression in this population.51, 52 In a study of 210 dialysis patients, of whom 100 had at least 1 prior episode of elevated depressive symptoms, 12.8% reported family or other personal issues, and 10.7% reported financial difficulties as contributing factors to depression.56

Biological

Several studies have supported a bidirectional association between inflammation and depression in chronic illness.32 This association is particularly relevant for patients with CKD and ESRD, in whom inflammatory levels are high,65 and for whom inflammation appears to predict poor health outcomes such as CKD progression and mortality.65, 66

Another potential biological mechanism that may lead to depression in patients with CKD and ESRD is the direct effect of comorbid cerebrovascular disease, which is highly prevalent in patients with kidney disease,67 on the mood regulatory functions of the brain.68 For example, specific poststroke lesions in the left anterior and left basal ganglia, and those close to the frontal pole, have been associated with depression.68 Cerebrovascular disease may also indirectly affect mood by increasing inflammation.48, 68

Mechanisms by Which Depression Associates With Adverse Outcomes

There are several potential biologic mechanisms that can explain the association between depression and poorer medical outcomes in patients with CKD and ESRD. As described, depression can increase inflammation, which in turn can accelerate atherosclerosis and potentially lead to cardiovascular events.55 Depression is also implicated in the modulation of vascular tone by altering serotonin levels and autonomic nervous system function, increasing platelet aggregation, altering cortisol and norepinephrine production, all of which can lead to cardiovascular events and stroke.55

There are also behavioral consequences of depression, which may adversely affect medical outcomes. In patients with ESRD, depression has been associated with medication noncompliance,69 dietary indiscretion,55 interdialytic weight gain,55 and missed dialysis.28, 70 In a study of 65 hemodialysis patients and 94 kidney transplant patients, Cukor et al. evaluated the association between psychological measures and self-reported medication adherence,69 and found that depressive symptoms were a significant independent predictor of lower medication adherence. Furthermore, in a study of 295 hemodialysis patients by Kimmel et al., worsening depressive symptoms were correlated with worse compliance with total dialysis time.70 Noncompliance with self-care behaviors could worsen blood pressure, blood glucose, cholesterol, bone metabolism, anemia, phosphorus, and volume status in patients with CKD and ESRD, and ultimately lead to adverse health outcomes.

Treatment

Depression is undertreated in both patients with CKD and those with ESRD. In an analysis of 1099 adults with CKD stage 3 to 4 and elevated depressive symptoms who were enrolled in the CRIC and HCRIC studies, only 31% reported receipt of antidepressant medication.20 In another study of 928 adults with ESRD on long-term hemodialysis and physician-diagnosed depression, only 34.9% were receiving antidepressant medication.49

Depression Treatment in Chronic Illness

In the general population and in patients with chronic illness, treatment with antidepressants or psychotherapy significantly improves depressive symptoms and psychosocial outcomes,71, 72, 73 and treating with a combination of both has been shown to be more effective than either alone.74 The impact of depression treatment on other medical outcomes has been evaluated in several studies, with mixed results.75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80 Interestingly, studies of collaborative care models (psychiatric treatment, delivered by a mental health specialist and a case manager, combined with medical care), have shown consistent improvements in medical outcomes.75, 81, 82

The safety and efficacy of depression treatment in patients with CKD or ESRD cannot be extrapolated from prior studies of patients with other chronic illnesses because elevated serum creatinine is often an exclusion criterion in such studies,80 and because the pharmacokinetics of antidepressant medications vary depending on the level of kidney function.83 Unfortunately, few studies have examined the safety and efficacy of treating depression in patients with CKD or ESRD, and these studies are limited by small sample sizes, lack of control groups, and selection and drop-out bias.84 A recent systematic review by Palmer et al. concluded that data on the benefits and harms of antidepressant therapy in patients with ESRD are sparse and currently inconclusive.85

Pharmacokinetics of Antidepressant Medications in Kidney Disease

In general, antidepressant medications are protein bound, have large volumes of distribution, and are metabolized by the liver.18 These characteristics make them unlikely to be removed by dialysis.18 There are, however, important ways in which impaired kidney function modifies the pharmacokinetics of antidepressant medications.83 Gastric alkalinization caused by elevated urea levels and changes in gastrin, as well as the use of phosphate binders or antacids, can decrease the oral bioavailability of antidepressants. Volume overload often observed in patients with CKD and ESRD can alter the volume of distribution of antidepressants. Retention of uremic solutes can change the albumin-binding characteristics of antidepressants and increase their free fraction. Kidney disease may slow their chemical degradation. Finally, for antidepressants with any degree of renal clearance, excretion may be impaired. Unfortunately, few studies have evaluated the optimal dosing of antidepressants in patients with abnormal kidney function.84 In general, providers should monitor closely for side effects and drug interactions whenever they are administered to patients with kidney disease.

In a systematic review by Nagler et al., 28 studies evaluating pharmacokinetics of antidepressants in CKD or ESRD were identified.84 The authors reported that drug clearance was markedly reduced for selegiline, amitriptylinoxide (metabolite of amitriptyline), venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine (metabolite of venlafaxine), milnacipran, bupropion, reboxetine, and tianeptine. The review also found that no studied antidepressants were substantially removed by dialysis. A brief review of the pharmacokinetics of selected antidepressant classes is provided below, and dosing guidelines are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Antidepressant medication safety, dosing, and efficacy in CKD and ESRD

| Drug class, generic | Dose in CKD1–484 | Dose in CKD 5 and ESRD84 | Efficacy studies | Class adverse effects84, 85, 86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI): | _Common:_Insomnia, restlessness, nausea, headache, GI upset, sexual dysfunction, activation (mainly with fluoxetine and sertraline)_Rare:_SIADH, increased bleeding risk, extrapyramidal symptoms, serotonin syndrome (in combination with other serotonergic drugs), and QT prolongation (seen with doses >40 mg of citalopram) | |||

| Sertraline | No dosage adjustment required:50–200 mg/d | Similar to CKD 1–4. Start at 25 mg/d and consider decreasing maximum dose | Three prospective efficacy studies: -50 Patients with depression on HD were randomized to sertraline or placebo. At the end of 12 wk, sertraline significantly improved BDI-II scores (47.5% reduction)108 -In a study by Wuerth et al., 22 patients on PD with interview-based depression were included, and 11 patients completed a 12-week course of therapy with an antidepressant medication (7 sertraline, 2 bupropion, and 2 nefazodone). BDI scores decreased significantly from a mean of 17.1 to 8.6109 -25 Patients with interview-defined depression on PD received sertraline 50 mg/d for 12 wk. BDI scores significantly improved from 22.4 to 15.7110 | |

| Paroxetine | IR:10–40 mg/d111CR:12.5–50 mg/d112 | Similar to CKD 1–4 | -34 Patients with MDD received paroxetine and psychotherapy for 8 wk. Intervention significantly improved depressive symptoms (HRSD 16.6 to 15.1 pre−post treatment) and nutritional markers113 | |

| Citalopram | No dosage adjustment required: 10–40 mg/d | Use with caution: no recommendation available | -44 Patients on hemodialysis with a HADS score ≥8 were randomly assigned to citalopram 20 mg/d for 3 mo or psychological training. Both citalopram and psychological training significantly reduced HADS scores at the end of 3 mo114 | |

| Fluoxetine | No dosage adjustment required: 20–60 mg/d | Similar to CKD 1–4 | Two prospective efficacy studies: -6 Depressed patients on hemodialysis completed 8 wk of treatment with 20 mg fluoxetine. Fluoxetine improved depressive symptoms by more than 25%115 -14 Patients with major depression and on dialysis were randomly assigned to treatment with fluoxetine or placebo for 8 wk. Improvement in depression was statistically significant at 4 wk but not 8 wk89 | |

| Escitalopram | No dosage adjustment required: 10–20 mg/d116 | Use with caution: no dosage recommendation available | -58 ESRD patients were randomized to escitalopram or placebo. Escitalopram significantly improved HRDS scores compared to placebo117 | |

| Tricyclics (TCA) | Anticholinergic effects, orthostasis, sedation, cardiotoxicity | |||

| Imipramine | No dosage adjustment required: 100–300 mg/day | Similar to CKD 1–4 | No efficacy data | |

| Nortriptyline | No dosage adjustment required: 75–150 mg/d | Similar to CKD 1-4 | No efficacy data | |

| Desipramine | No dosage adjustment required: 100–300 mg/d | Use with caution—effects of metabolite accumulation | -8 Patients with ESRD on dialysis with major depression treated with desipramine for 7 wk. Recovery of major depression in 5 of 8 patients118 | |

| Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) | Similar to SSRIs plus increased BP. Liver toxicity seen with duloxetine | |||

| Venlafaxine | Normal dosage: 75–225 mg/deGFR 10–70: consider reducing total daily dose 25%–50%: 150–225 mg/d119 | Reduce total daily dose by 50% | No efficacy data | |

| Duloxetine | No adjustment required if eGFR > 30: 40–120 mg/d | Use not recommended with eGFR < 30 | No efficacy data | |

| Miscellaneous | Appetite stimulation, weight gain, sedation | |||

| Mirtazapine | No dosage adjustment recommended: 15–45 mg/d | Consider dose reduction;clearance reduced by 50% | No efficacy data | |

| Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors | Increased risk of seizures, insomnia, anxiety, decreased appetite | |||

| Bupropion | Consider reduced dose and/or frequency: 150–450 mg/d120 | Same as CKD 1–4 | Wuerth et al. described above; 2 patients were treated with bupropion109 |

Most of the data on pharmacokinetics of antidepressant medications in CKD or ESRD comes from studies of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which have shown that ESRD has no effect on the pharmacokinetics of fluoxetine, its active metabolite norfluoxetine, or citalopram.86 However, exposure to paroxetine is significantly prolonged when the creatinine clearance is <30 ml/min compared to >60 ml/min.86, 87

Selective serotononin−norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as venlafaxine, have been used to treat depression and neuropathic pain in patients with CKD and ESRD.86 The clearance of these medications is reduced in patients with ESRD, and therefore it is recommended that their dose be reduced by 50%.86 A pharmacokinetics study of 12 individuals with ESRD and 12 healthy controls found that the clearance of duloxetine was more than 2 times longer in patients with ESRD compared with controls.88 The product insert for duloxetine in the United States currently recommends not using this medication when the creatinine clearance is <30 ml/min, due to decreased clearance by the kidneys.86 However, regulatory agencies outside the United States have suggested that it can be used at lower doses with careful titration.88

Bupropion is a norepinephrine−dopamine reuptake inhibitor and a nicotinic antagonist used to treat depression and aid with smoking cessation. Pharmacokinetics studies of bupropion in CKD and ESRD patients are limited, but metabolites appear to accumulate in patients with ESRD, and dose reduction is likely necessary.86

Mirtazapine is a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant medication that has been used to treat depression and anxiety. It is also reported to have hypnotic effects and appetite stimulant effects. Although pharmacokinetic data are limited, it is likely that mirtazapine accumulates in individuals with CKD and ESRD and that dose reduction is therefore necessary.86

Although pharmacokinetic data and efficacy data exist for tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), both classes of medications and their metabolites can accumulate with impaired kidney function and cause serious side effects (Table 3).86 In addition, several severe drug−drug interactions, including use with other antidepressant medications, limit the utility of MAOI.18 For these reasons, both TCA and MAOI should not be considered first-line treatment for depression in patients with kidney disease.18

Efficacy Studies

In their systematic review, Nagler et al. identified 11 studies (1 randomized controlled trial [RCT], 1 abstract of an RCT, and 9 nonrandomized trials) evaluating the efficacy of antidepressants in patients with ESRD.84 The trials were small (ranging from 7 to 62 participants) and possibly confounded by selection and drop-out bias. None of these trials evaluated the efficacy of antidepressants in patients with CKD who were not treated with dialysis. The majority evaluated SSRIs. The sole published RCT, which enrolled 14 patients on hemodialysis, showed no difference in efficacy or safety measures between fluoxetine and placebo.89 All 9 noncontrolled, nonrandomized trial studies reported a benefit of antidepressants. The authors concluded that evidence of effectiveness of antidepressants in patients with stage 3 to 5 CKD (including ESRD) was insufficient. Since the publication of the above review, Palmer et al. published a systematic review of RCTs comparing the efficacy of antidepressant medication versus placebo or psychological training in patients with ESRD.85 This review included 3 additional RCTs not included in the review by Nagler et al. In all 3 RCTs, SSRIs significantly improved depressive symptoms. Trials evaluating the efficacy of antidepressants in kidney disease are summarized in Table 3.

More data are needed prior to making definitive recommendations on the efficacy of antidepressants in patients with kidney disease. We identified 4 ongoing clinical trials (3 enrolling patients with ESRD, and 1 enrolling patients with CKD not on dialysis) examining their effectiveness (Table 4).90, 91 Hopefully, more efficacy data will emerge soon. Based on current data, we agree with recommendations by Hedayati et al. and Kimmel et al. that SSRIs should be considered the first line of treatment for depression in patients with kidney disease.17, 18

Table 4.

Ongoing trials of depression treatment interventions from ClinicalTrials.gov90, 91,a

| Authors | Sample characteristics | Intervention | Follow-up | Primary outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedayati et al.91 | 180 Patients with MDE and stage 3–5 CKD not on dialysis | RCT of sertraline versus placebo | 12 wk | Depressive symptom severity as measured by the QIDS-C-16 |

| Delgado et al.90 | 40 HD patients with MDE | RCT of fluoxetine versus bupropion | 12 wk | Depression severity as measured by the 25-item HDRS |

| Jassal et al.90 | 60 Incident dialysis patients (within 12 wk of first dialysis treatment) | RCT of escitalopram versus placebo | 26 wk | Recruitment rates and protocol complianceSecondary outcomes: adverse events, hospitalization days, mortality, and changes in depression and QOL |

| Mehrotra et al.90 | 400 HD patients with MDE or dysthymiaunderwent an engagement interview180 HD patients with MDE or dysthymiarandomized to intervention | Individual CBT versus sertraline | 12 wk | Percentage of patients who initiate treatmentDepressive symptom severity as measured by the QIDS-C-16 |

Nonpharmacological Interventions

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a structured psychotherapy intervention designed to treat dysfunctional cognitions, negative emotions, and maladaptive behaviors that are present in patients with depression. Several studies of CBT in patients with ESRD (none in CKD) have shown an improvement of depressive symptoms with its use.92, 93, 94 In a randomized, crossover trial of 65 patients on hemodialysis, Cukor et al. evaluated the effects of 10 individual CBT sessions in participants with elevated depressive affect (BDI-II > 10), delivered by a psychologist over 3 months.94 At the end of treatment, only 11% of patients in the treatment-first group were depressed, compared with 62% in the waitlist group. These results are consistent with a 9-month RCT of 85 dialysis patients in which CBT significantly improved depressive symptoms and quality of life compared to control.93 In addition to treating depression, CBT has successfully improved quality of life, sleep quality, inflammation, and adherence to fluid restrictions in patients with ESRD.93, 94, 95

Several trials have evaluated the effect of exercise therapy and increased dialysis frequency on depressive symptoms in patients with ESRD, with mixed results.96, 97, 98, 99 A recent review of exercise interventions in patients with ESRD found 4 RCT in which depressive symptoms were measured.96 In 3 of 4 of these interventions, exercise improved depressive symptoms. With regard to increasing dialysis frequency, the largest study to date evaluated depressive symptoms and mental health in 245 hemodialysis patients from the Frequent Hemodialysis Network trials and 83 patients from the Nocturnal Trials. Frequent (6 times weekly) hemodialysis was found to improve self-reported mental health but not depressive symptoms at 12 months.97 However, in a recent systematic review by Slinin et al., 7 studies (2 RCT) evaluating the effect of more frequent hemodialysis on depression were identified.99 The authors concluded that increasing dialysis frequency did not improve clinical outcomes including depression. For all studies evaluating the effect of exercise or more frequent dialysis on depression, a diagnosis of depression was not required for study entry. It remains unclear whether patients with pre-existing depression would benefit from these interventions, as these individuals may lack the motivation to engage in exercise or more frequent dialysis.

Barriers to Treatment

There are several barriers to treatment in patients with depression and CKD or ESRD. Perhaps in part because of the already high medication burden in these patients, at least 40% of patients may not want treatment for their depression.91, 100, 101 Furthermore, those who accept behavioral treatment may not be willing to follow certain recommendations, such as home exercises, for the treatment to be successful.91 In addition, nephrologists often do not start therapy for depression in their patients with CKD or ESRD because they believe that this is the responsibility of the primary care provider.101, 102 In a cross-sectional survey study of hemodialysis providers by Green et al., less than 20% of providers reported treating known sexual dysfunction or depression “most” or “all” of the time, and 82% believed that it was the responsibility of the primary care provider to manage depression.102 This is particularly problematic for the 65% to 80% of hemodialysis patients who do not have primary care providers.101, 103, 104 Finally, combined behavioral and medical interventions often require resources that are not readily available at a CKD clinic or dialysis center, including psychologists able to deliver behavioral therapy in multiple languages. Ultimately, novel treatment strategies that incorporate behavioral techniques into routine medical care such as cognitive-behavioral strategies integrated with CKD education are needed. This model has been successfully used in patients with diabetes and other chronic illnesses.81, 105

Future Studies

There are many gaps that remain in our understanding of depression in patients with CKD and ESRD. We find that the most pressing areas of research involve understanding the mechanisms of depression and preventing and treating depression in these populations. With regard to the mechanisms of depression, current research has not elucidated causative factors for depression or the direction of the relationship between CKD and depression. Understanding these mechanisms could help to both prevent and treat depression. With regard to treatment, no large, well-designed studies have evaluated depression prevention and treatment interventions in patients with CKD or ESRD. This paucity of data may be due, in part, to prioritization of medical outcomes, such as progression to ESRD, over patient-centered outcomes such as quality of life or mood disorders, by the nephrology community.106 There is reason for optimism, however. Recently, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) has funded several clinically focused trials in patients with kidney disease that are designed to engage patients in clinical kidney research.107 We hope that this new focus on patient-centered outcomes in clinical kidney research will lead to a greater understanding of how depression affects patients with kidney disease, and whether depression treatment will improve their mood, quality of life, and medical outcomes.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgment

ACR is funded by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K23DK094829 Award.

References

- 1.Kimmel P.L. Psychosocial factors in dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1599–1613. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590041599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonikian M., Metaxaki P., Papavasileiou D. Effects of interleukin-6 on depression risk in dialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31:303–308. doi: 10.1159/000285110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer S., Vecchio M., Craig J.C. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int. 2013;84:179–191. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cukor D., Fruchter Y., Ver Halen N. A preliminary investigation of depression and kidney functioning in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;122:139–145. doi: 10.1159/000349940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee Y.J., Kim M.S., Cho S. Association of depression and anxiety with reduced quality of life in patients with predialysis chronic kidney disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:363–368. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai Y.C., Chiu Y.W., Hung C.C. Association of symptoms of depression with progression of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:54–61. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.02.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer M.J., Kimmel P.L., Greene T. Elevated depressive affect is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes among African Americans with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;80:670–678. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belayev L.Y., Mor M.K., Sevick M.A. Longitudinal associations of depressive symptoms and pain with quality of life in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2015;19:216–224. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- 10.Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B., Gibbon M. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittchen H.U. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO−Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K.H. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33. [quiz: 34–57] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watnick S., Wang P.L., Demadura T. Validation of 2 depression screening tools in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:919–924. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedayati S.S., Bosworth H.B., Kuchibhatla M. The predictive value of self-report scales compared with physician diagnosis of depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1662–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedayati S.S., Minhajuddin A.T., Toto R.D. Validation of depression screening scales in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:433–439. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craven J.L., Rodin G.M., Littlefield C. The Beck Depression Inventory as a screening device for major depression in renal dialysis patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1988;18:365–374. doi: 10.2190/m1tx-v1ej-e43l-rklf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen S.D., Norris L., Acquaviva K. Screening, diagnosis, and treatment of depression in patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:1332–1342. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03951106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedayati S.S., Yalamanchili V., Finkelstein F.O. A practical approach to the treatment of depression in patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2012;81:247–255. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kop W.J., Seliger S.L., Fink J.C. Longitudinal association of depressive symptoms with rapid kidney function decline and adverse clinical renal disease outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:834–844. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03840510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer M.J., Xie D., Jordan N. Factors associated with depressive symptoms and use of antidepressant medications among participants in the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) and Hispanic-CRIC Studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:27–38. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu M.K., Katon W., Young B.A. Diabetes self-care, major depression, and chronic kidney disease in an outpatient diabetic population. Nephron Clin Pract. 2013;124:106–112. doi: 10.1159/000355551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedayati S.S., Minhajuddin A.T., Afshar M. Association between major depressive episodes in patients with chronic kidney disease and initiation of dialysis, hospitalization, or death. JAMA. 2010;303:1946–1953. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiang H.H., Guo H.R., Livneh H. Increased risk of progression to dialysis or death in CKD patients with depressive symptoms: a prospective 3-year follow-up cohort study. J Psychosom Res. 2015;79:228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith S.R., Svetkey L.P., Dennis V.W. Racial differences in the incidence and progression of renal diseases. Kidney Int. 1991;40:815–822. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowie C.C., Port F.K., Wolfe R.A. Disparities in incidence of diabetic end-stage renal disease according to race and type of diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1074–1079. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910193211603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopes A.A., Bragg J., Young E. Depression as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney Int. 2002;62:199–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer M.J., Kimmel P.L., Greene T. Sociodemographic factors contribute to the depressive affect among African Americans with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2010;77:1010–1019. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weisbord S.D., Mor M.K., Sevick M.A. Associations of depressive symptoms and pain with dialysis adherence, health resource utilization, and mortality in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:1594–1602. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00220114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weisbord S.D., Fried L.F., Unruh M.L. Associations of race with depression and symptoms in patients on maintenance haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:203–208. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waraich P., Goldner E.M., Somers J.M. Prevalence and incidence studies of mood disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:124–138. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pratt L.A., Brody D.J. Depression in the U.S. household population, 2009-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2014:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katon W.J. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:7–23. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/wkaton. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M.W., Ho R.C., Cheung M.W. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farrokhi F., Abedi N., Beyene J. Association between depression and mortality in patients receiving long-term dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63:623–635. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hedayati S.S., Bosworth H.B., Briley L.P. Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int. 2008;74:930–936. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hedayati S.S., Grambow S.C., Szczech L.A. Physician-diagnosed depression as a correlate of hospitalizations in patients receiving long-term hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:642–649. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulware L.E., Liu Y., Fink N.E. Temporal relation among depression symptoms, cardiovascular disease events, and mortality in end-stage renal disease: contribution of reverse causality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:496–504. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00030505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Troidle L., Watnick S., Wuerth D.B. Depression and its association with peritonitis in long-term peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:350–354. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00661-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurella M., Kimmel P.L., Young B.S. Suicide in the United States end-stage renal disease program. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:774–781. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Artom M., Moss-Morris R., Caskey F. Fatigue in advanced kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2014;86:497–505. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leinau L., Murphy T.E., Bradley E. Relationship between conditions addressed by hemodialysis guidelines and non-ESRD-specific conditions affecting quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:572–578. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03370708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pisoni R.L., Wikstrom B., Elder S.J. Pruritus in haemodialysis patients: international results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3495–3505. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szentkiralyi A., Molnar M.Z., Czira M.E. Association between restless legs syndrome and depression in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bornivelli C., Aperis G., Giannikouris I. Relationship between depression, clinical and biochemical parameters in patients undergoing haemodialysis. J Ren Care. 2012;38:93–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2012.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Navaneethan S.D., Vecchio M., Johnson D.W. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported sexual dysfunction in CKD: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:670–685. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seidel U.K., Gronewold J., Volsek M. Physical, cognitive and emotional factors contributing to quality of life, functional health and participation in community dwelling in chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Porter A.C., Lash J.P., Xie D. Predictors and outcomes of health-related quality of life in adults with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1154–1162. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09990915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katon W.J. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:216–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopes A.A., Albert J.M., Young E.W. Screening for depression in hemodialysis patients: associations with diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2047–2053. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hedayati S.S., Minhajuddin A.T., Toto R.D. Prevalence of major depressive episode in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:424–432. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cole M.G., Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1147–1156. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicholas S.B., Kalantar-Zadeh K., Norris K.C. Socioeconomic disparities in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22:6–15. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kiberd B. The chronic kidney disease epidemic: stepping back and looking forward. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2967–2973. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006020123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Golden S.H., Lazo M., Carnethon M. Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. JAMA. 2008;299:2751–2759. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hedayati S.S., Finkelstein F.O. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of depression in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:741–752. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song M.K., Ward S.E., Hladik G.A. Depressive symptom severity, contributing factors, and self-management among chronic dialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2016;20:286–292. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chilcot J., Davenport A., Wellsted D. An association between depressive symptoms and survival in incident dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1628–1634. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shirazian S., Diep R., Jacobson A.M. Awareness of chronic kidney disease and depressive symptoms: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2005-2010. Am J Nephrol. 2016;44:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000446929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beddhu S., Baird B.C., Zitterkoph J. Physical activity and mortality in chronic kidney disease (NHANES III) Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1901–1906. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01970309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friedman A.N. Obesity in patients undergoing dialysis and kidney transplantation. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20:128–134. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silverwood R.J., Pierce M., Thomas C. Association between younger age when first overweight and increased risk for CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:813–821. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Orth S.R., Hallan S.I. Smoking: a risk factor for progression of chronic kidney disease and for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in renal patients—absence of evidence or evidence of absence? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:226–236. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03740907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kessler R.C., Crum R.M., Warner L.A. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koning S.H., Gansevoort R.T., Mukamal K.J. Alcohol consumption is inversely associated with the risk of developing chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015;87:1009–1016. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Di Lullo L., Rivera R., Barbera V. Sudden cardiac death and chronic kidney disease: from pathophysiology to treatment strategies. Int J Cardiol. 2016;217:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cachofeiro V., Goicochea M., de Vinuesa S.G. Oxidative stress and inflammation, a link between chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2008;111:S4–S9. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bugnicourt J.M., Godefroy O., Chillon J.M. Cognitive disorders and dementia in CKD: the neglected kidney-brain axis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:353–363. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012050536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Whyte E.M., Mulsant B.H. Post stroke depression: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and biological treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:253–264. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cukor D., Rosenthal D.S., Jindal R.M. Depression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1223–1229. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kimmel P.L., Peterson R.A., Weihs K.L. Psychosocial factors, behavioral compliance and survival in urban hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1998;54:245–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kupfer D.J., Frank E., Phillips M.L. Major depressive disorder: new clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Lancet. 2012;379:1045–1055. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60602-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baumeister H., Hutter N., Bengel J. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for depression in patients with diabetes mellitus and depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD008381. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008381.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rayner L., Price A., Evans A. Antidepressants for depression in physically ill people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD007503. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007503.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cuijpers P., Dekker J., Hollon S.D. Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:1219–1229. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09r05021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Katon W.J., Von Korff M., Lin E.H. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams J.W., Jr., Katon W., Lin E.H. The effectiveness of depression care management on diabetes-related outcomes in older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:1015–1024. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-12-200406150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lustman P.J., Anderson R.J., Freedland K.E. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:934–942. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jorge R.E., Robinson R.G., Arndt S. Mortality and poststroke depression: a placebo-controlled trial of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1823–1829. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berkman L.F., Blumenthal J., Burg M. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3106–3116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Glassman A.H., O'Connor C.M., Califf R.M. Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA. 2002;288:701–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Katon W.J., Lin E.H., Von Korff M. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Atlantis E., Fahey P., Foster J. Collaborative care for comorbid depression and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004706. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cohen L.M., Tessier E.G., Germain M.J. Update on psychotropic medication use in renal disease. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:34–48. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nagler E.V., Webster A.C., Vanholder R. Antidepressants for depression in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety with recommendations by European Renal Best Practice (ERBP) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:3736–3745. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palmer S.C., Natale P., Ruospo M. Antidepressants for treating depression in adults with end-stage kidney disease treated with dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016:CD004541. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004541.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eyler R.F., Unruh M.L., Quinn D.K. Psychotherapeutic agents in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2015;28:417–426. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Doyle G.D., Laher M., Kelly J.G. The pharmacokinetics of paroxetine in renal impairment. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1989;350:89–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb07181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lobo E.D., Heathman M., Kuan H.Y. Effects of varying degrees of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of duloxetine: analysis of a single-dose phase I study and pooled steady-state data from phase II/III trials. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:311–321. doi: 10.2165/11319330-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Blumenfield M., Levy N.B., Spinowitz B. Fluoxetine in depressed patients on dialysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27:71–80. doi: 10.2190/WQ33-M54T-XN7L-V8MX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.ClinicalTrials.gov. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=depression+kidney&Search=Search. Accessed September 5, 2016.

- 91.Hedayati S.S., Daniel D.M., Cohen S. Rationale and design of A Trial of Sertraline vs. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for End-stage Renal Disease Patients with Depression (ASCEND) Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;47:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen H.Y., Chiang C.K., Wang H.H. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for sleep disturbance in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:314–323. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Duarte P.S., Miyazaki M.C., Blay S.L. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy is an effective treatment for major depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2009;76:414–421. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cukor D., Ver Halen N., Asher D.R. Psychosocial intervention improves depression, quality of life, and fluid adherence in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:196–206. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen H.Y., Cheng I.C., Pan Y.J. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for sleep disturbance decreases inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2011;80:415–422. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barcellos F.C., Santos I.S., Umpierre D. Effects of exercise in the whole spectrum of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8:753–765. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Unruh M.L., Larive B., Chertow G.M. Effects of 6-times-weekly versus 3-times-weekly hemodialysis on depressive symptoms and self-reported mental health: Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) Trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61:748–758. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jaber B.L., Lee Y., Collins A.J. Effect of daily hemodialysis on depressive symptoms and postdialysis recovery time: interim report from the FREEDOM (Following Rehabilitation, Economics and Everyday-Dialysis Outcome Measurements) Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:531–539. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Slinin Y., Greer N., Ishani A. Timing of dialysis initiation, duration and frequency of hemodialysis sessions, and membrane flux: a systematic review for a KDOQI clinical practice guideline. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:823–836. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chiu Y.W., Teitelbaum I., Misra M. Pill burden, adherence, hyperphosphatemia, and quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1089–1096. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00290109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Weisbord S.D., Mor M.K., Green J.A. Comparison of symptom management strategies for pain, erectile dysfunction, and depression in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis: a cluster randomized effectiveness trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:90–99. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04450512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Green J.A., Mor M.K., Shields A.M. Renal provider perceptions and practice patterns regarding the management of pain, sexual dysfunction, and depression in hemodialysis patients. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:163–167. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nespor S.L., Holley J.L. Patients on hemodialysis rely on nephrologists and dialysis units for maintenance health care. ASAIO J. 1992;38:M279–M281. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199207000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shah N., Dahl N.V., Kapoian T. The nephrologist as a primary care provider for the hemodialysis patient. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37:113–117. doi: 10.1007/s11255-004-0875-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Weinger K., Beverly E.A., Lee Y. The effect of a structured behavioral intervention on poorly controlled diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1990–1999. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Moss A.H., Davison S.N. How the ESRD quality incentive program could potentially improve quality of life for patients on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:888–893. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07410714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cukor D., Cohen L.M., Cope E.L. Patient and other stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research institute funded studies of patients with kidney diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:17031712. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09780915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Taraz M., Khatami M.R., Dashti-Khavidaki S. Sertraline decreases serum level of interleukin-6 (IL-6) in hemodialysis patients with depression: results of a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;17:917–923. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wuerth D., Finkelstein S.H., Ciarcia J. Identification and treatment of depression in a cohort of patients maintained on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(05)80018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Atalay H., Solak Y., Biyik M. Sertraline treatment is associated with an improvement in depression and health-related quality of life in chronic peritoneal dialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:527–536. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9686-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.GlaxoSmithKline. Product Information: PAXIL(R) oral tablets, suspension, paroxetine hydrochloride oral tablets, suspension. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2010

- 112.GlaxoSmithKline. Product Information: PAXIL CR(R) controlled-release oral tablets, paroxetine hydrochloride controlled-release oral tablets. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2010.

- 113.Koo J.R., Yoon J.Y., Joo M.H. Treatment of depression and effect of antidepression treatment on nutritional status in chronic hemodialysis patients. Am J Med Sci. 2005;329:1–5. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hosseini S.H., Espahbodi F., Mirzadeh Goudarzi S.M. Citalopram versus psychological training for depression and anxiety symptoms in hemodialysis patients. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2012;6:446–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Levy N.B., Blumenfield M., Beasley C.M., Jr. Fluoxetine in depressed patients with renal failure and in depressed patients with normal kidney function. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:8–13. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(95)00073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Forest Laboratories, Inc. Product Information: LEXAPRO(R) Oral solution, oral tablets, escitalopram oxalate oral solution, oral tablets. St Louis, MO: Forest Laboratories, Inc.; 2009.

- 117.Yazici A.E., Erdem P., Erdem A. Efficacy and tolerability of escitalopram in depressed patients with end stage renal disease: an open placebo-controlled study. Psikofarmakoloji Bulteni. 2012;22:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kennedy S.H., Craven J.L., Rodin G.M. Major depression in renal dialysis patients: an open trial of antidepressant therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50:60–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. Product Information: EFFEXOR XR(R) extended-release oral capsules, venlafaxine hydrochloride extended-release oral capsules. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2008.

- 120.GlaxoSmithKline. Product Information: WELLBUTRIN oral tablets, bupropion HCl oral tablets (per FDA). Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2013.