Bioactive Components in Moringa Oleifera Leaves Protect against Chronic Disease (original) (raw)

Abstract

Moringa Oleifera (MO), a plant from the family Moringacea is a major crop in Asia and Africa. MO has been studied for its health properties, attributed to the numerous bioactive components, including vitamins, phenolic acids, flavonoids, isothiocyanates, tannins and saponins, which are present in significant amounts in various components of the plant. Moringa Oleifera leaves are the most widely studied and they have shown to be beneficial in several chronic conditions, including hypercholesterolemia, high blood pressure, diabetes, insulin resistance, non-alcoholic liver disease, cancer and overall inflammation. In this review, we present information on the beneficial results that have been reported on the prevention and alleviation of these chronic conditions in various animal models and in cell studies. The existing limited information on human studies and Moringa Oleifera leaves is also presented. Overall, it has been well documented that Moringa Oleifera leaves are a good strategic for various conditions associated with heart disease, diabetes, cancer and fatty liver.

Keywords: Moringa Oleifera, bioactive components, hepatic steatosis, heart disease, diabetes, cancer

1. Introduction

Moringa, a native plant from Africa and Asia, and the most widely cultivated species in Northwestern India, is the sole genus in the family Moringaceae [1]. It comprises 13 species from tropical and subtropical climates, ranging in size from tiny herbs to massive trees. The most widely cultivated species is Moringa Oleifera (MO) [1]. MO is grown for its nutritious pods, edible leaves and flowers and can be utilized as food, medicine, cosmetic oil or forage for livestock. Its height ranges from 5 to 10 m [1].

Several studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects in humans [2]. MO has been recognized as containing a great number of bioactive compounds [3,4] The most used parts of the plant are the leaves, which are rich in vitamins, carotenoids, polyphenols, phenolic acids, flavonoids, alkaloids, glucosinolates, isothiocyanates, tannins and saponins [5]. The high number of bioactive compounds might explain the pharmacological properties of MO leaves. Many studies, in vitro and in vivo, have confirmed these pharmacological properties [5].

The leaves of MO are mostly used for medicinal purposes as well as for human nutrition, since they are rich in antioxidants and other nutrients, which are commonly deficient in people living in undeveloped countries [6]. MO leaves have been used for the treatment of various diseases from malaria and typhoid fever to hypertension and diabetes [7].

The roots, bark, gum, leaf, fruit (pods), flowers, seed, and seed oil of MO are reported to have various biological activities, including protection against gastric ulcers [8], antidiabetic [9], hypotensive [10] and anti-inflammatory effects [11]. It has also been shown to improve hepatic and renal functions [12] and the regulation of thyroid hormone status [13]. MO leaves also protect against oxidative stress [14], inflammation [15], hepatic fibrosis [16], liver damage [17], hypercholesterolemia [18,19], bacterial activity [20], cancer [14] and liver injury [21].

2. Bioactive Components in Moringa Oleifera

2.1. Vitamins

Fresh leaves from MO are a good source of vitamin A [22]. It is well established that vitamin A has important functions in vision, reproduction, embryonic growth and development, immune competence and cell differentiation [23]. MO leaves are a good source of carotenoids with pro-vitamin A potential [24].

MO leaves also contain 200 mg/100 g of vitamin C, a concentration greater than what is found in oranges [22,25]. MO leaves also protect the body from various deleterious effects of free radicals, pollutants and toxins and act as antioxidants [26]. MO fresh leaves are a good source of vitamin E, with concentrations similar to those found in nuts [21]. This is important because vitamin E not only acts as an antioxidant, but it has been shown to inhibit cell proliferation [27].

2.2. Polyphenols

The dried leaves of MO are a great source of polyphenol compounds, such as flavonoids and phenolic acids.

Flavonoids, which are synthesized in the plant as a response to microbial infections, have a benzo-γ-pyrone ring as a common structure [28,29]. Intake of flavonoids has been shown to protect against chronic diseases associated with oxidative stress, including cardiovascular disease and cancer. MO leaves are a good source of flavonoids [30].

The main flavonoids found in MO leaves are myrecytin, quercetin and kaempferol, in concentrations of 5.8, 0.207 and 7.57 mg/g, respectively [31,32].

Quercetin is found in dried MO leaves, at concentrations of 100 mg/100 g, as quercetin-3-_O_-β-d-glucoside (iso-quercetin or isotrifolin) [33,34]. Quercetin is a strong antioxidant, with multiple therapeutic properties [35]. It has hypolipidemic, hypotensive, and anti-diabetic properties in obese Zucker rats with metabolic syndrome [36]. It can reduce hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis in high cholesterol or high-fat fed rabbits [37,38]. It can protect insulin-producing pancreatic β cells from Streptozotocin (STZ) induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in rats [39].

Phenolic acids are a sub-group of phenolic compounds, derived from hydroxybenzoic acid and hydroxycinnamic acid, naturally present in plants, and these compounds have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic and anticancer properties [40,41]. In dried leaves, Gallic acid is the most abundant, with a concentration of 1.034 mg/g of dry weight. The concentration of chlorogenic and caffeic acids range from 0.018 to 0.489 mg/g of dry weight and 0.409 mg/g of dry weight, respectively [42,43].

Chlorogenic acid (CGA) is an ester of dihydrocinnamic acid and a major phenolic acid in MO [44]. CGA has a role in glucose metabolism. It inhibits glucose-6-phosphate translocase in rat liver, reducing hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis [45]. CGA has also been found to lower post-prandial blood glucose in obese Zucker rats [46] and to reduce the glycemic response in rodents [47]. CGA has anti-dyslipidemic properties, as it reduces plasma total cholesterol and triglycerides (TG) in obese Zucker rats or mice fed a high fat diet [48] and reverses STZ-induced dyslipidemia in diabetic rats [41].

2.3. Alkaloids, Glucosinolates and Isothiocyonates

Alkaloids are a group of chemical compounds, which contain mostly basic nitrogen atoms. Several of these compounds, including N,α-l-rhamnopyranosyl vincosamide, phenylacetonitrile pyrrolemarumine,4′-hydroxyphenylethanamide-α-l-rhamnopyranoside and its glucopyranosyl derivative, have been isolated from Moringa Oleifera leaves [49,50].

Glucosinolates are a group of secondary metabolites in plants [51]. Both glucosinolates and isothiocyanates have been found to have important health-promoting properties [52].

2.4. Tannins

Tannins are water-soluble phenolic compounds that precipitate alkaloids, gelatin and other proteins. Their concentrations in dried leaves range between 13.2 and 20.6 g tannin/kg [53] being a little higher in freeze-dried leaves [54]. Tannins have been reported to have anti-cancer, antiatherosclerotic, anti-inflammatory and anti-hepatoxic properties [55].

2.5. Saponins

MO leaves are also a good source of saponins, natural compounds made of an isoprenoidal-derived aglycone, covalently linked to one or more sugar moieties [56]. The concentrations of saponins in MO freeze-dried leaves range between 64 and 81 g/kg of dry weight [57]. Saponins have anti-cancer properties [58].

3. Effects of Moringa Oleifera on the Prevention of Chronic Disease

3.1. Hypolipidemic Effects

Many bioactive compounds found in MO leaves may influence lipid homeostasis. Phenolic compounds, as well as flavonoids, have important roles in lipid regulation [59]. They are involved in the inhibition of pancreatic cholesterol esterase activity, thereby reducing and delaying cholesterol absorption, and binding bile acids, by forming insoluble complexes and increasing their fecal excretion, thereby decreasing plasma cholesterol concentrations [60]. The extracts of MO have shown hypolipidemic activity, due to inhibition of both lipase and cholesterol esterase, thus showing its potential for the prevention and treatment of hyperlipidemia [61].

MO has a strong effect on lipid profile through cholesterol reducing effects. Cholesterol homeostasis is maintained by two processes: cholesterol biosynthesis, in which 3-hydroxymethyl glutaryl CoA (HMG-Co-A) reductase catalyzes the rate limiting process and cholesterol absorption of both dietary cholesterol and cholesterol cleared from the liver through biliary secretion. The activity of HMG-CoA reductase was depressed by the ethanolic extract of MO, further supporting its hypolipidemic action [62]. Moringa Oleifera (MO) leaves also contain the bioactive β-sitosterol, with documented cholesterol lowering effects, which might have been responsible for the cholesterol lowering action in plasma of high fat fed rats [18].

Saponins, found in MO leaves, prevented the absorption of cholesterol, by binding to this molecule and to bile acids, causing a reduction in the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids and increasing their fecal excretion [9]. The increased bile acid excretion is offset by enhanced bile acid synthesis from cholesterol in the liver, leading to the lowering of plasma cholesterol [9].

3.2. Antioxidant Effects

Due to the high concentrations of antioxidants present in MO leaves [14,63,64], they can be used in patients with inflammatory conditions, including cancer, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases [17,65]. The β carotene found in MO leaves has been shown to act as an antioxidant. The antioxidants have the maximum effect on the damage caused by free radicals only when they are ingested in combination. A combination of antioxidants found in MO leaves was proven to be more effective than a single antioxidant, possibly due to synergistic mechanisms and increased antioxidant cascade mechanisms [22,66,67]. A recent study in children demonstrated that MO leaves could be an important source of vitamin A [68].

The extract of MO leaves also contains tannins, saponins, flavonoids, terpenoids and glycosides, which have medicinal properties. These compounds have been shown to be effective antioxidants, antimicrobial and anti-carcinogenic agents [69,70]. Phenolic compounds are known to act as primary antioxidants [71], due to their properties for the inactivation of lipid free radicals or prevention of the decomposition of hydroperoxides into free radicals, due to their redox properties. These properties play a key role in neutralizing free radicals, quenching singlet or triplet oxygen, or decomposing peroxides [72,73].

The radical scavenging and antioxidant activities of the aqueous and aqueous ethanol extracts of freeze-dried leaves of MO, from different agro-climatic regions, were investigated by Siddhuraju and Becker [74]. They found that different leaf extracts inhibited 89.7–92.0% of peroxidation of linoleic acid and had scavenging activities on superoxide radicals in a dose-dependent manner in the β-carotene-linoleic acid system. Iqbal and Bhanger [75] showed that the environmental temperature and soil properties have significant effects on antioxidant activity of MO leaves.

3.3. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effect

The extract of MO leaves inhibited human macrophage cytokine production (tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8), which were induced by cigarette smoke and by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [76]. Further, Waterman et al. [77] reported that both MO concentrate and isothiocyanates decreased the gene expression and production of inflammatory markers in RAW macrophages.

The extracts of MO leaves stimulated both cellular and humoral immune responses in cyclophosphamide-induced immunodeficient mice, through increases in white blood cells, percent of neutrophils and serum immunoglobulins [78,79]. In addition, quercetin may have been involved in the reduction of the inflammatory process by inhibiting the action of neutral factor kappa-beta (NF-kβ) and subsequent NF-kB-dependent downstream events and inflammation [80]. Further, fermentation of MO appears to enhance the anti-inflammatory properties of MO [81]. C57BL/6 mice, fed for 10 weeks with distilled water, fermented and non-fermented MO [81]. Investigators reported decreases in the mRNA levels of inflammatory cytokines and reductions in endoplasmic reticulum stress in those animals fed the fermented product.

3.4. Hepato-Protective Effects

The methanol extract of MO leaves has a hepatoprotective effect, which might be due to the presence of quercetin [14,67]. MO leaves had substantial effects on the levels of aspartate amino transferase (AST), alanine amino transferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), in addition to reductions in lipids and lipid peroxidation levels in the liver of rats [18].

MO leaves have been shown to reduce plasma ALT, AST, ALP and creatinine [82,83] and to ameliorate hepatic and kidney damage induced by drugs. In rats, co-treated with MO leaves and NiSO4, in order to induce nephrotoxicity, similar findings were observed [84]. Also, Das et al. [75] observed the same reductions in hepatic enzymes in rats fed a high fat diet, in combination with MO leaves. Also, the administration of the extract of MO leaves in mice was followed by decreases in serum ALT, AST, ALP, and creatinine [85,86]. In guinea pigs, treatment of MO leaves prevented non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in a model of hepatic steatosis, as measured by lower concentrations of hepatic cholesterol and triglycerides in animals treated with MO compared to controls [87]. This lowering of hepatic lipids was associated with lower inflammation and expression of genes involved in lipid uptake and inflammation [87]. Further, the MO treated guinea pigs had lower concentrations of plasma ASP. In contrast, MO leaves did not reduce the inflammation of lipid accumulation in the adipose tissue of guinea pigs [88].

3.5. Anti-Hyperglycemic (Antidiabetic) Effect

Many compounds found in MO leaves might be involved in glucose homeostasis. For example, isothiocyanates have been reported to reduce insulin resistance as well as hepatic gluconeogenesis [89,90]. Phenolic acids and flavonoids affect glucose homeostasis, influencing β-cell mass and function, and increasing insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues [91,92]. Phenolic compounds, flavonoids and tannins also inhibit intestinal sucrase and to a certain extent, pancreatic α-amylase activities [56].

The beneficial activities of MO leaves on carbohydrate metabolism have been shown by different mechanisms, including preventing and restoring the integrity and function of β-cells, increasing insulin activity, improving glucose uptake and utilization [57]. Hypoglycemic and antihyperglycemic activity of the leaves of MO might be due to the presence of terpenoids, which are involved in the stimulation of β-cells and the subsequent secretion of insulin. Also, flavonoids have been shown to play an important role in the hypoglycemic action [93]. In another study, where diabetes was induced peritoneally by injection with streptozotocin, rats were fed the equivalent of 250 mg/kg of MO for 6 weeks, using control and diabetic animals [94]. The groups consuming MO extract had significant decreases in malonaldehyde and improvements in the inflammatory cytokines—TNF-α and IL-6—when compared to control animals [94].

3.6. Hypotensive Effects

MO leaves contain several bioactive compounds, which have been used for stabilizing blood pressure, including nitrile, mustard oil glycosides and thiocarbamate glycosides. The isolated four pure compounds, niazinin A, niazinin B, niazimicin and niazinin A + B—from ethanol extract of MO leaves showed a blood pressure lowering effect in rats, mediated possibly through a calcium antagonist effect [14,95]. A recent study reported that MO reduced vascular oxidation in spontaneously hypertensive rats [96].

3.7. Effects on Ocular Diseases

The major cause of blindness, which ranges from impaired dark adaptation to night blindness, is vitamin A deficiency. MO leaves, pods and leaf powder contain high concentrations of vitamin A, which can help to prevent night blindness and eye problems. Also, consumption of leaves with oils improved vitamin A nutrition and delayed the development of cataracts [14].

3.8. Anticancer Effects

MO has been studied for its chemopreventive properties and has been shown to inhibit the growth of several human cancer cells [97]. The capacity of MO leaves to protect organisms and cells from oxidative DNA damage, associated with cancer and degenerative diseases, has been reported in several studies [98]. Khalafalla et al. [99] found that the extract of MO leaves inhibited the viability of acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia and hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Several bioactive compounds, including 4-(α-l-rhamnosyloxy) benzyl isothiocyanate, niazimicin and β-sitosterol-3-_O_-β-d-glucopyranoside present in MO, may be responsible for its anti-cancer properties [100]. MO leaf extract has also been proven to be efficient in pancreatic and breast cancer cells [98,99].

In pancreatic cells, MO was shown to contain the growth of pancreatic cancer cells, by inhibiting NF-ĸB signaling as well as increasing the efficacy of chemotherapy, by enhancing the effect of the drug in these cells [101]. In breast cancer cells, the antiproliferative effects of MO were also demonstrated [102]. A recent study by Abd-Rabou et al. [103] evaluated the effects of various extracts from Moringa Oleifera, including leaves and roots, and preparations of nanocomposites of these compounds against HepG, breast MCF7 and colorectal HCT116/Caco2 cells. All these preparations were effective on their cytotoxic impact, as measured by apoptosis [103]. Several animal studies have also confirmed the efficacy of Moringa Oleifera leaves in preventing cancer in rats with hepatic carcinomas induced by diethyl nitrosamine [104] and in suppressing azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in mice [105]. A list of some bioactive components present in MO leaves, their postulated actions in the animal model used, their protection against a specific disease and the corresponding reference are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bioactive Components in Moringa Oleifera and their Positive Effects on Chronic Disease.

| Compounds | Postulated Function | Model Used | Disease Protection | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids: Quercitin | Hypolipidemic and anti-diabetic properties | Zucker rat | Diabetes | [36] |

| Lower hyperlipidemia | Rabbits | Atherosclerosis | [37,38] | |

| Decrease expression of DGAT | Guinea Pigs | NAFLD | [80] | |

| Inhibition of cholesterol esterase and α-glucosidase | In vitro study | Cardiovascular disease and Diabetes | [60] | |

| Inhibits activation of NF-kB | High fat fed Mice | Cardiovascular disease | [74] | |

| Chlorogenic Acid | Glucose lowering effect | Diabetic rats | Diabetes | [45] |

| Cholesterol lowering in plasma and liver | Zucker rat | Cardiovascular disease | [46] | |

| Decrease expression of CD68, SERBP1c | Guinea pigs | NAFLD | [87] | |

| Anti-obesity properties | High-fat induced obesity rats | Obesity | [49] | |

| Inhibit enzymes linked to T2D | Diabetes | [90] | ||

| Alkaloids | Cardioprotection | Cardiotoxic-induced rats | Cardiovascular disease | [49] |

| Tannins | Anti-inflammatory | Rats | Cardiovascular/Cancer | [54] |

| Isothiocyanates | Decreased expression of inflammatory markers | RAW Macrophages | Cardiovascular disease | [76] |

| Reduction in insulin resistance | Mice | Diabetes | [88] | |

| Inhibition of NF-kB signaling | Cancer breast cells | Cancer | [99] | |

| Β-Sitosterol | Decrease cholesterol absorption | High-fat fed rats | Cardiovascular disease | [18] |

3.9. Protection Against Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

It is recognized that the monoaminegistic system has a modulatory role in memory processing and that this system is disturbed by AD [106]. Some plants, including MO, have been demonstrated to enhance memory by nootropics activity and protect against the oxidative stress present in AD [107] Ganguly et al. [108] have an established model for AD involving the infusion of colchicine into the brain of rats and they demonstrated that MO led to the alteration of brain monoamines and electrical patterns. A recent study was conducted to evaluate the effects of an isothiocynate isolated from MO, both in a mouse model of PD and in RAW 264.7 macrophages stimulated with LPS [109]. Results demonstrated great efficacy of a bioactive compound in MO, which results from myrosinase hydrolysis in favorably modulating the inflammatory and apoptotic pathways as well as oxidative stress [109].

4. Conclusions

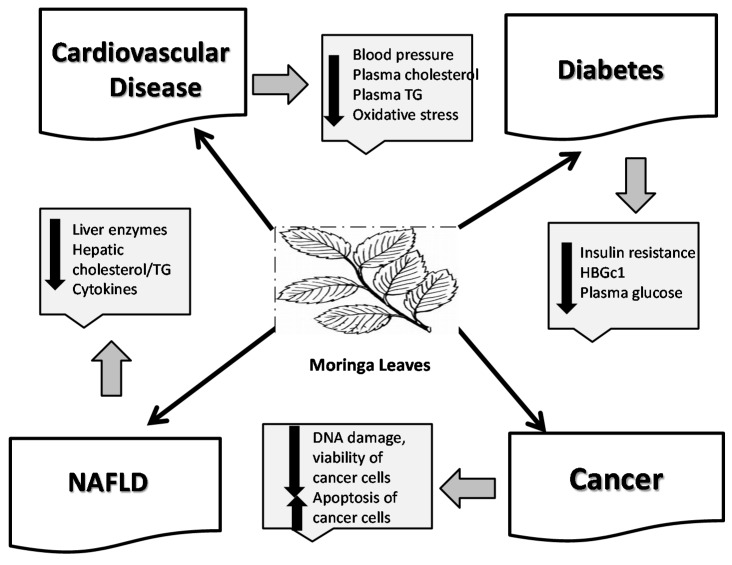

In summary, there are a number of animal studies documenting the effects of MO leaves in protecting against cardiovascular disease, diabetes, NAFLD, Alzheimer’s, hypertension and others, due the actions of the bioactive components in preventing lipid accumulation, reducing insulin resistance and inflammation. Additional studies in humans, including clinical trials are needed to confirm these effects of MO on chronic diseases. In addition, some studies have found that the compounds in MO may also protect against Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. A summary of the effects of the bioactive component of MO leaves in protecting against these conditions is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Protective effects of MO leaves against chronic diseases: cardiovascular disease, by lowering plasma lipids including triglycerides (TG) [45,60] decreasing blood pressure [92] and reducing oxidative stress [73]; diabetes, by lowering plasma glucose [61], reducing insulin resistance [89] and increasing β cell function [90]; NAFLD, by reducing hepatic lipids [82,87], reducing liver enzymes [82,83,88] and decreasing hepatic inflammation [88] and cancer, by reducing DNA damage [97], viability of cancer cells [99,100] and increasing apoptosis [104,105].

Author Contributions

Marcela Vergara-Jimenez searched the literature, provided a number of references and the input in the final version of the paper; Manal Mused Almatrafi contributed substantially to the writing of the paper; Maria Luz Fernandez reviewed all articles, did a summary of the most relevant literature, put together all the information, produced the final version of this manuscript and created the Table and the Figure.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Padayachee B., Baijnath H. An overview of the medicinal importance of Moringaceae. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012;6:5831–5839. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stohs S., Hartman M.J. Review of the Safety and Efficacy of Moringa oleífera. Phytother. Res. 2015;29:796–804. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saini R.K., Sivanesan I., Keum Y.S. Phytochemicals of Moringa oleifera: A review of their nutritional, therapeutic and industrial significance. 3 Biotech. 2016;6 doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0526-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin C., Martin G., Garcia A., Fernández T., Hernández E., Puls L. Potential applications of Moringa oleifera. A critical review. Pastosy Forrajes. 2013;36:150–158. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leone A., Spada A., Battezzati A., Schiraldi A., Aristil J., Bertoli S. Cultivation, genetic, ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Moringa oleifera Leaves: An overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:12791–12835. doi: 10.3390/ijms160612791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popoola J.O., Obembe O.O. Local knowledge, use pattern and geographical distribution of Moringa oleifera Lam. (Moringaceae) in Nigeria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;150:682–691. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sivasankari B., Anandharaj M., Gunasekaran P. An ethnobotanical study of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants used by the village peoples of Thoppampatti, Dindigul district, Tamilnadu, India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;153:408–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pal S.K., Mukherjee P.K., Saha B.P. Studies on the antiulcer activity of Moringa oleifera leaf extract on gastric ulcer models in rats. Phytother. Res. 1995;9:463–465. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2650090618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oyedepo T.A., Babarinde S.O., Ajayeoba T.A. Evaluation of the antihyperlipidemic effect of aqueous leaves extract of Moringa oleifera in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Int. J. Biochem. Res. Rev. 2013;3:162–170. doi: 10.9734/IJBCRR/2013/3639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faizi S., Siddiqui B., Saleem R., Aftab K., Shaheen F., Gilani A. Hypotensive constituents from the pods of Moringa oleifera. Planta Med. 1998;64:225–228. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao K.S., Mishra S.H. Anti-inflammatory and antihepatoxic activities of the roots of Moringa pterygosperma Gaertn. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 1998;60:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett R.N., Mellon F.A., Foidl N., Pratt J.H., Dupont M.S., Perkins L., Kroon P.A. Profiling glucosinolates and phenolics in vegetative and reproductive tissues of the multi-purpose trees Moringa oleifera L. (horseradish tree) and Moringa stenopetala L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:3546–3553. doi: 10.1021/jf0211480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tahiliani P., Kar A. Role of Moringa oleifera leaf extract in the regulation of thyroid hormone status in adult male and female rats. Pharmacol. Res. 2000;41:319–323. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anwar F., Latif S., Ashraf M., Gilani A.H. Moringa oleifera: A food plant with multiple medicinal uses. Phytother. Res. 2007;21:17–25. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahajan S., Banerjee A., Chauhan B., Padh H., Nivsarkar M., Mehta A. Inhibitory effect of N-butanol fraction of Moringa oleifera Lam seeds on ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation in a guinea pig model of asthma. Int. J. Toxicol. 2009;28:519–527. doi: 10.1177/1091581809345165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamza A.A. Ameliorative effects of Moringa oleifera Lam seed extract on liver fibrosis in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010;48:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pari L., Kumar N.A. Hepatoprotective activity of Moringa oleifera on antitubercular drug-induced liver damage in rats. J. Med. Food. 2002;5:171–177. doi: 10.1089/10966200260398206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halaby M.S., Metwally E.M., Omar A.A. Effect of Moringa oleifera on serum lipids and kidney function of hyperlipidemic rats. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2013;9:5189–5198. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okwari O., Dasofunjo K., Asuk A., Alagwu E., Mokwe C. Anti-hypercholesterolemic and hepatoprotective effect of aqueous leaf extract of Moringa oleifera in rats fed with thermoxidized palm oil diet. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2013;8:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter A., Samuel W., Peter A., Joseph O. Antibacterial activity of Moringa oleifera and Moringa stenopetala methanol and N-hexane seed extracts on bacteria implicated in water borne diseases. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2011;5:153–157. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Efiong E.E., Igile G.O., Mgbeje B.I.A., Out E.A., Ebong P.E. Hepatoprotective and anti-diabetic effect of combined extracts of Moringa oleifera and Vernoniaamygdalina in streptozotocin-induced diabetic albino Wistar rats. J. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;4:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferreira P.M.P., Farias D.F., Oliveira J.T.D.A., Carvalho A.D.F.U. Moringa oleifera: Bioactive compounds and nutritional potential. Rev. Nutr. 2008;21:431–437. doi: 10.1590/S1415-52732008000400007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alvarez R., Vaz B., Gronemeyer H., de Lera A.R. Functions, therapeutic applications, and synthesis of retinoids and carotenoids. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:1–125. doi: 10.1021/cr400126u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slimani N., Deharveng G., Unwin I., Southgate D.A., Vignat J., Skeie G., Salvini S., Parpinel M., Møller A., Ireland J., et al. The EPIC nutrient database project (ENDB): A first attempt to standardize nutrient databases across the 10 European countries participating in the EPIC study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;61:1037–1056. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramachandran C., Peter K.V., Gopalakrishnan P.K. Drumstick (Moringa oleifera): A multipurpose Indian vegetable. Econ. Bot. 1980;34:276–283. doi: 10.1007/BF02858648. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chambial S., Dwivedi S., Shukla K.K., John P.J., Sharma P. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: An overview. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2013;28:314–328. doi: 10.1007/s12291-013-0375-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borel P., Preveraud D., Desmarchelier C. Bioavailability of vitamin E in humans: An update. Nutr. Rev. 2013;71:319–331. doi: 10.1111/nure.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S., Pandey A.K. Chemistry and biological activities of flavonoids: An overview. Sci. World J. 2013;2013:162750. doi: 10.1155/2013/162750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bovicelli P., Bernini R., Antonioletti R., Mincione E. Selective halogenation of flavanones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:5563–5567. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)01117-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pandey K.B., Rizvi S.I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2009;2:270–278. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sultana B., Anwar F. Flavonols (kaempeferol, quercetin, myricetin) contents of selected fruits, vegetables and medicinal plants. Food Chem. 2008;108:879–884. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coppin J.P., Xu Y., Chen H., Pan M.H., Ho C.T., Juliani R., Simon J.E., Wu Q. Determination of flavonoids by LC/MS and anti-inflammatory activity in Moringa oleifera. J. Funct. Foods. 2013;5:1892–1899. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lako J., Trenerry V.C., Wahlqvist M., Wattanapenpaiboon N., Sotheeswaran S., Premier R. Phytochemical flavonols, carotenoids and the antioxidant properties of a wide selection of Fijian fruit, vegetables and other readily available foods. Food Chem. 2007;101:1727–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.01.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atawodi S.E., Atawodi J.C., Idakwo G.A., Pfundstein B., Haubner R., Wurtele G., Bartsch H., Owen R.W. Evaluation of the polyphenol content and antioxidant properties of methanol extracts of the leaves, stem, and root barks of Moringa oleifera Lam. J. Med. Food. 2010;13:710–716. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2009.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bischoff S.C. Quercetin: Potentials in the prevention and therapy of disease. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2008;11:733–740. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32831394b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rivera L., Moron R., Sanchez M., Zarzuelo A., Galisteo M. Quercetin ameliorates metabolic syndrome and improves the inflammatory status in obese Zucker rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2081–2087. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juzwiak S., Wojcicki J., Mokrzycki K., Marchlewicz M., Bialecka M., Wenda-Rozewicka L., Gawrońska-Szklarz B., Droździk M. Effect of quercetin on experimental hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis in rabbits. Pharmacol. Rep. 2005;57:604–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamada C., da Silva E.L., Ohnishi-Kameyama M., Moon J.H., Terao J. Attenuation of lipid peroxidation and hyperlipidemia by quercetin glucoside in the aorta of high cholesterol-fed rabbit. Free Radic. Res. 2005;39:185–194. doi: 10.1080/10715760400019638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coskun O., Kanter M., Korkmaz A., Oter S. Quercetin, a flavonoid antioxidant, prevents and protects streptozotocin-induced oxidative stress and beta-cell damage in rat pancreas. Pharmacol. Res. 2005;51:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El-Seedi H.R., El-Said A.M., Khalifa S.A., Göransson U., Bohlin L., Borg-Karlson A.K., Verpoorte R. Biosynthesis, natural sources, dietary intake, pharmacokinetic properties, and biological activities of hydroxycinnamic acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:10877–10895. doi: 10.1021/jf301807g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verma S., Singh A., Mishra A. Gallic acid: Molecular rival of cancer. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2013;35:473–485. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prakash D., Suri S., Upadhyay G., Singh B.N. Total phenol, antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of some medicinal plants. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007;58:18–28. doi: 10.1080/09637480601093269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh B.N., Singh B.R., Singh R.L., Prakash D., Dhakarey R., Upadhyay G., Singh H.B. Oxidative DNA damage protective activity, antioxidant and anti-quorum sensing potentials of Moringa oleifera. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009;47:1109–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amaglo N.K., Bennett R.N., LoCurto R.B., Rosa E.A.S., LoTurco V., Giuffrid A., LoCurto A., Crea F., Timpo G.M. Profiling selected phytochemicals and nutrients in different tissues of the multipurpose tree Moringa oleifera L., grown in Ghana. Food Chem. 2010;122:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.03.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karthikesan K., Pari L., Menon V.P. Combined treatment of tetrahydrocurcumin and chlorogenic acid exerts potential antihyperglycemic effect on streptozotocin-nicotinamide-induced diabetic rats. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2010;29:23–30. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2010_01_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Sotillo Rodriguez D.V., Hadley M. Chlorogenic acid modifies plasma and liver concentrations of: Cholesterol, triacylglycerol, and minerals in (fa/fa) Zucker rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002;13:717–726. doi: 10.1016/S0955-2863(02)00231-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tunnicliffe J.M., Eller L.K., Reimer R.A., Hittel D.S., Shearer J. Chlorogenic acid differentially affects postprandial glucose and glucose-dependent insulin otropic polypeptide response in rats. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011;36:650–659. doi: 10.1139/h11-072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho A.S., Jeon S.M., Kim M.J., Yeo J., Seo K.I., Choi M.S., Lee M.K. Chlorogenic acid exhibits anti-obesity property and improves lipid metabolism in high-fat diet-induced-obese mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010;48:937–943. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panda S., Kar A., Sharma P., Sharma A. Cardioprotective potential of N, α-l-rhamnopyranosyl vincosamide, an indole alkaloid, isolated from the leaves of Moringa oleifera in isoproterenol induced cardiotoxic rats: In vivo and in vitro studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:959–962. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sahakitpichan P., Mahidol C., Disadee W., Ruchirawat S., Kanchanapoom T. Unusual glycosides of pyrrole alkaloid and 4′-hydroxyphenylethanamide from leaves of Moringa oleifera. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:791–795. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forster N., Ulrichs C., Schreiner M., Muller C.T., Mewis I. Development of a reliable extraction and quantification method for glucosinolates in Moringa oleifera. Food Chem. 2015;166:456–464. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dinkova-Kostova A.T., Kostov R.V. Glucosinolates and isothiocyanates in health and disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2012;18:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teixeira E.M.B., Carvalho M.R.B., Neves V.A., Silva M.A., Arantes-Pereira L. Chemical characteristics and fractionation of proteins from Moringa oleifera Lam. leaves. Food Chem. 2014;147:51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richter N., Siddhuraju P., Becker K. Evaluation of nutritional quality of moringa (Moringa oleifera Lam.) leaves as an alternative protein source for Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) Aquaculture. 2003;217:599–611. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(02)00497-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adedapo A.A., Falayi O.O., Oyagvemi A.A., Kancheva V.D., Kasaikina O.T. Evaluation of the analgesic, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, phytochemical and toxicological properties of the methanolic leaf extract of commercially processed Moringa oleifera in some laboratory animals. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015;26:491–499. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2014-0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Augustin J.M., Kuzina V., Andersen S.B., Bak S. Molecular activities, biosynthesis and evolution of triterpenoid saponins. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:435–457. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Makkar H.P.S., Becker K. Nutritional value and anti-nutritional components of whole and ethanol extracted Moringa oleifera Leaves. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 1996;63:211–228. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(96)01023-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tian X., Tang H., Lin H., Cheng G., Wang S., Zhang X. Saponins: The potential chemotherapeutic agents in pursuing new anti-glioblastoma drugs. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2013;13:1709–1724. doi: 10.2174/13895575113136660083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siasos G., Tousoulis D., Tsigkou V., Kokkou E., Oikonomou E., Vavuranakis M., Basdra E.K., Papavassiliou A.G., Stefanadis C. Flavonoids in atherosclerosis: An overview of their mechanisms of action. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013;20:2641–2660. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320210003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adisakwattana S., Chanathong B. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity and lipid-lowering mechanisms of Moringa oleifera Leaf extract. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011;15:803–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toma A., Makonnen E., Debella A., Tesfaye B. Antihyperglycemic Effect on Chronic Administration of Butanol Fraction of Ethanol Extract of Moringa stenopetala Leaves in Alloxan Induced Diabetic Mice. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012;2:S1606–S1610. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60461-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hassarajani S., Souza T.D., Mengi S.A. Efficacy study of the bioactive fraction (F-3) of Acorus calamus in hyperlipidemia. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2007;39:196–200. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mensah J.K., Ikhajiagbe B., Edema N.E., Emokhor J. Phytochemical, nutritional and antibacterial properties of dried leaf powder of Moringa oleifera (Lam.) from Edo Central Province, Nigeria. J. Nat. Prod. Plant Resour. 2012;2:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bamishaiye E.I., Olayemi F.F., Awagu E.F., Bamshaiye O.M. Proximate and phytochemical composition of Moringa oleifera leaves at three stages of maturation. Adv. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2011;3:233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Posmontie B. The medicinal qualities of Moringa oleifera. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2011;25:80–87. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0b013e31820dbb27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mishra G., Singh P., Verma R., Kumar R.S., Srivastava S., Khosla R.L. Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological properties of Moringa oleifera plant: An overview. Der Pharmacia Lettre. 2011;3:141–164. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tejas G.H., Umang J.H., Payal B.N., Tusharbinu D.R., Pravin T.R. A panoramic view on pharmacognostic, pharmacological, nutritional, therapeutic and prophylactic values of Moringa olifera Lam. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2012;3:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lopez-Teros V., Ford J.L., Green M.H., Tang G., Grusak M.A., Quihui-Cota L., Muzhingi T., Paz-Cassini M., Astiazaran-Garcia H. Use of a “Super-child” Approach to Assess the Vitamin A Equivalence of Moringa oleifera Leaves, Develop a Compartmental Model for Vitamin A Kinetics, and Estimate Vitamin A Total Body Stores in Young Mexican Children. J. Nutr. 2017 doi: 10.3945/jn.117.256974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ayoola G.A., Coker H.A.B., Adesegun S.A., Adepoju-Bello A.A., Obaweya K., Ezennia E.C. Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activities of some selected medicinal plants used for malaria therapy in southwestern Nigeria. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2008;7:1019–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Davinelli S., Bertoglio J.C., Zarrelli A., Pina R., Scapagnini G. A randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of an anthocyanin-maqui berry extract (Delphinol®) on oxidative stress biomarkers. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2015;34(Suppl. 1):28–33. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2015.1080108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murillo A.G., Fernandez M.L. The relevance of dietary polyphenols in cardiovascular protection. Curr. Pharmacol. Rev. 2017;23:2444–2452. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170329144307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pokorny J. Introduction. In: Pokorny J., Yanishlieva N., Gordon N.H., editors. Antioxidant in Foods: Practical Applications. Woodhead Publishing Limited; Cambridge, UK: 2001. pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zheng W., Wang S.Y. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in selected herbs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:5165–5170. doi: 10.1021/jf010697n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Siddhuraju P., Becker K. Antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of total phenolic constituents from three different agroclimatic origins of drumstick tree (Moringa oleifera Lam.) leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:2144–2155. doi: 10.1021/jf020444+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iqbal S., Bhanger M.I. Effect of season and production location on antioxidant activity of Moringa oleifera leaves grown in Pakistan. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006;19:544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2005.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kooltheat N., Sranujit R.P., Chumark P., Potup P., Laytragoon-Lewin N., Usuwanthim K. An ethyl acetate fraction of Moringa oleifera Lam. Inhibits human macrophage cytokine production induced by cigarette smoke. Nutrients. 2014;6:697–710. doi: 10.3390/nu6020697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Waterman C., Cheng D.M., Rojas-Silva P., Poulev A., Dreifus J., Lila M.A., Raskin I. Stable, water extractable isothiocyanates from Moringa oleifera leaves attenuate inflammation in vitro. Phytochemistry. 2014;103:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sudha P., Asdaq S.M., Dhamingi S.S., Chandrakala G.K. Immunomodulatory activity of methanolic leaf extract of Moringa oleifera in animals. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010;54:133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gupta A., Gautam M.K., Singh R.K., Kumar M.V., Rao C.H.V., Goel R.K., Anupurba S. Immunomodulatory effect of Moringa oleifera Lam. extract on cyclophosphamide induced toxicity in mice. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2010;48:1157–1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Das N., Sikder K., Ghosh S., Fromenty B., Dey S. Moringa oleifera Lam. leaf extract prevents early liver injury and restores antioxidant status in mice fed with high-fat diet. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2012;50:404–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Joung H., Kim B., Park H., Lee K., Kim H.H., Sim H.C., Do H.J., Hyun C.K., Do M.S. Fermented Moringa oleifera Decreases Hepatic Adiposity and Ameliorates Glucose Intolerance in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. J. Med. Food. 2017;20:439–447. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2016.3860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharifudin S.A., Fakurazi S., Hidayat M.T., Hairuszah I., Moklas M.A., Arulselvan P. Therapeutic potential of Moringa oleifera extracts against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Pharm. Biol. 2013;51:279–288. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2012.720993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ouedraogo M., Lamien-Sanou A., Ramde N., Ouédraogo A.S., Ouédraogo M., Zongo S.P., Goumbri O., Duez P., Guissou P.I. Protective effect of Moringa oleifera Leaves against gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rabbits. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2013;65:335–339. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adeyemi O.S., Elebiyo T.C. Moringa oleifera supplemented diets prevented nickel-induced nephrotoxicity in Wistar rats. J. Nutr. Metab. 2014;2014:958621. doi: 10.1155/2014/958621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oyagbemi A.A., Omobowale T.O., Azeez I.O., Abiola J.O., Adedokun R.A., Nottidge H.O. Toxicological evaluations of methanolic extract of Moringa oleifera Leaves in liver and kidney of male Wistar rats. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013;24:307–312. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2012-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Asiedu-Gyekye I.J., Frimpong-Manso S., Awortwe C., Antwi D.A., Nyarko A.K. Micro- and macroelemental composition and safety evaluation of the nutraceutical Moringa oleifera Leaves. J. Toxicol. 2014;2014:786979. doi: 10.1155/2014/786979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Almatrafi M.M., Vergara-Jimenez M., Murillo A.G., Norris G.H., Blesso C.N., Fernandez M.L. Moringa leaves prevent hepatic lipid accumulation and inflammation in guinea pigs by reducing the expression of genes involved in lipid Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1330. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Almatrafi M.M., Vergara-Jimenez M., Smyth J.A., Medina-Vera I., Fernandez M.L. Moringa olifeira leaves do not alter adipose tissue colesterol accumulation or inflammation in guinea pigs fed a hypercholesterolemic diet. EC Nutr. 2017;18:1330. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Waterman C., Rojas-Silva P., Tumer T., Kuhn P., Richard A.J., Wicks S., Stephens J.M., Wang Z., Mynatt R., Cefalu W., et al. Isothiocyanate-rich Moringa oleifera extract reduces weight gain, insulin resistance and hepatic gluconeogenesis in mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015;59:1013–1024. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fabio G.D., Romanucci V., De Marco A., Zarrelli A. Triterpenoids from Gymnema sylvestre and their pharmacological activities. Molecules. 2014;19:10956–10981. doi: 10.3390/molecules190810956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Oh Y.S., Jun H.S. Role of bioactive food components in diabetes prevention: Effects on Beta-cell function and preservation. Nutr. Metab. Insights. 2014;7:51–59. doi: 10.4137/NMI.S13589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oboh G., Agunloye O.M., Adefegha S.A., Akinyemi A.J., Ademiluyi A.O. Caffeic and chlorogenic acids inhibit key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes (in vitro): A comparative study. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015;26:165–170. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2013-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Manohar V.S., Jayasree T., Kishore K.K., Rupa L.M., Dixit R., Chandrasekhar N. Evaluation of hypoglycemic and antihyperglycemic effect of freshly prepared aqueous extract of Moringa oleifera leaves in normal and diabetic rabbits. J. Chem. Pharmacol. Res. 2012;4:249–253. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Omodanisi E.I., Aboua Y.G., Oguntibeju O.O. Assessment of the Anti-Hyperglycaemic, Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activities of the Methanol Extract of Moringa oleifera in Diabetes-Induced Nephrotoxic Male Wistar Rats. Molecules. 2017;22:439. doi: 10.3390/molecules22040439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dubey D.K., Dora J., Kumar A., Gulsan R.K. A Multipurpose Tree-Moringa oleifera. Int. J. Pharm. Chem. Sci. 2013;2:415–423. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Randriamboavonjy J.I., Rio M., Pacaud P., Loirand G., Tesse A. Moringa oleifera seeds attenuate vascular oxidative and nitrosative stresses in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017;2017:4129459. doi: 10.1155/2017/4129459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Karim N.A., Ibrahim M.D., Kntayya S.B., Rukayadi Y., Hamid H.A., Razis A.F. Moringa oleifera Lam: Targeting Chemoprevention. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016;17:3675–3686. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sidker K., Sinha M., Das N., Das D.K., Datta S., Dey S. Moringa oleifera Leaf extract prevents in vitro oxidative DNA damage. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2013;6:159–163. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Khalafalla M.M., Abdellatef E., Dafalla H.M., Nassrallah A., Aboul-Enein K.M., Lightfoot D.A., El-Deeb F.E., El-Shemyet H.A. Active principle from Moringa oleifera Lam leaves effective against two leukemias and a hepatocarcinoma. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010;9:8467–8471. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Abdull Razis A.F., Ibrahim M.D., Kantayya S.B. Health benefits of Moringa oleifera. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8571–8576. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.20.8571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Berkovich L., Earon G., Ron I., Rimmon A., Vexler A., Lev-Ari S. Moringa oleifera aqueous leaf extract down-regulates nuclear factor-ĸB and increases cytotoxic effect of chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Adebayo I.A., Arsad H., Samian M.R. Antiproliferative effect on breast cancer (MCF7) of Moringa oleifera seed extracts. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2017;14:282–287. doi: 10.21010/ajtcam.v14i2.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Abd-Rabou A.A., Abdalla A.M., Ali N.A., Zoheir K.M. Moringa oleifera root induces cancer apoptosis more effectively than leave nanocomposites and its free counterpart. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017;18:2141–2149. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.8.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sadek K.M., Abouzed T.K., Abouelkhair R., Nasr S. The chemo-prophylactic efficacy of an ethanol Moringa oleifera leaf extract against hepatocellular carcinoma in rats. Pharm. Biol. 2017;55:1458–1466. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2017.1306713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Budda S., Butryee C., Tuntipopipat S., Rungsipipat A., Wangnaithum S., Lee J.S., Kupradinun P. Suppressive effects of Moringa oleifera Lam pod against mouse colon carcinogenesis induced by azoxymethane and dextran sodium sulfate. Asian Pac. J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:3221–3228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Obulesu M., Rao D.M. Effect of plant extracts on Alzheimer’s disease: An insight into therapeutic avenues. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 2011;2:56–61. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.80102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ganguly R., Hazra R., Ray K., Guha D. Effect of Moringa oleifera in experimental model of Alzheimer’s disease: Role of antioxidants. Ann. Neurosci. 2005;12:36–39. doi: 10.5214/ans.0972.7531.2005.120301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ganguly R., Guha D. Alteration of brain monoamines and EEG wave pattern in rat model of Alzheimer’s disease and protection by Moringa oleifera. Indian J. Med. Res. 2008;128:744–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Giacoipo S., Rajan T.S., De Nicola G.R., Iori R., Rollin P., Bramanti P., Mazzon E. The Isothiocyanate Isolated from Moringa oleifera Shows Potent Anti-Inflammatory Activity in the Treatment of Murine Subacute Parkinson’s Disease. Rejuvenation Res. 2017;20:50–63. doi: 10.1089/rej.2016.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]