Eukaryogenesis, a syntrophy affair (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2020 Jan 1.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Microbiol. 2019 Jul 1;4(7):1068–1070. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0495-5

Standfirst

Eukaryotes evolved from a symbiosis involving alphaproteobacteria and archaea phylogenetically nested within the Asgard clade. Two recent studies explore the metabolic capabilities of Asgard lineages, supporting refined symbiotic metabolic interactions that might have operated at the dawn of eukaryogenesis.

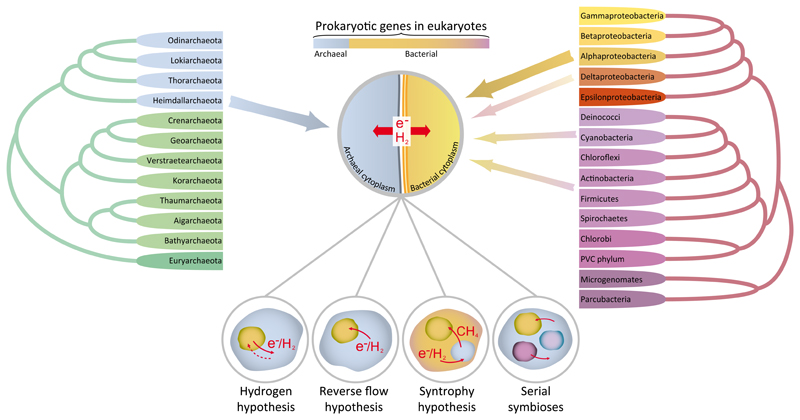

Eukaryogenesis, the evolutionary process leading to the origin of the eukaryotic cell, has remained elusive for a long time. The endosymbiotic origin of mitochondria and chloroplasts from, respectively, alphaproteobacteria and cyanobacteria became established forty years ago. However, models proposing the symbiotic origin of eukaryotes directly from bacterial and archaeal ancestors, such as Lynn Margulis’ serial endosymbiosis theory or the hydrogen and the syntrophy hypotheses, were considered heretical face to the prevailing orthodox view, that of a proto-eukaryotic lineage sister to archaea that had evolved all typical eukaryotic traits (e.g. phagocytosis, nucleus) except the mitochondrion1–3. In recent years, methodological advances and the exploration of microbial diversity in natural environments have allowed to reconstruct genomes of uncultured microbes from metagenomes and brought new light into eukaryogenesis by allowing the discovery of the Asgard archaea. These deep-branching archaea share more genes with eukaryotes than other archaea and phylogenomic analyses place eukaryotes within this clade4,5. This provides support for the occurrence of only two primary domains, bacteria and archaea, and for the symbiogenetic origin of eukaryotes6. According to this view, eukaryotes are mergers; they constitute a third, but secondary, domain of life. If the symbiogenetic origin of eukaryotes is now making its way to mainstream science, most existing models fail to propose plausible detailed evolutionary process and leave many questions unexplained2, starting by the specific nature of the symbiotic interaction at the origin of eukaryotes. The most detailed models in this sense were the hydrogen and the syntrophy hypotheses which, twenty years ago, converged in proposing a metabolic interaction based on interspecies hydrogen transfer from a bacterial fermenter to an archaeal methanogen7 (Figure 1). In the hydrogen hypothesis, that bacterium was the endosymbiotic ancestor of mitochondria; in the syntrophy model, that bacterium was the host that incorporated an archaeon (future nucleus) and a second endosymbiont (future mitochondrion). At that time, although the occurrence of metabolic symbioses (syntrophies) between methanogenic archaea and deltaproteobacteria was well known in oxygen-deprived systems, our knowledge about archaeal diversity and metabolism was extremely fragmentary. However, a plethora of archaeal phyla has been discovered since then. Although members of these lineages remain mostly uncultured, we can start unveiling their metabolic potential from genomes assembled from metagenomes of natural communities and proposing more plausible metabolic interactions at the onset of eukaryogenesis.

Figure 1. Metabolic symbiosis at the origin of eukaryotes.

Current phylogenomic evidence supports symbiotic models for the origin of the eukaryotic cell. Eukaryotic genomes are mosaics containing a substantial number of genes (~1,000) of archaeal and bacterial ancestry that can now be traced to specific lineages4,5,11. This information supports the idea that eukaryotes evolved from a symbiosis between a member of the recently described Asgard archaea more closely related (so far) to the Heimdallarchaeota and, at least, the facultatively aerobic alphaproteobacterium that gave rise to the mitochondrion. Comparative analyses of the Asgard archaeal metabolic potential allow Spang et al.8 and Bulzu et al.9 to conclude that Asgard archaea were primarily organoheterotrophic organisms that can produce and consume hydrogen. Some Heimdallarchaeota also gained the capability to use oxygen and nitrate as final electron acceptors by horizontal gene transfer in a later stage. Based on Asgard archaeal metabolic reconstruction and ecological considerations, Spang et al.8 propose the ‘reverse flow model’. This refined symbiogenetic model for the origin of eukaryotes invokes a metabolic symbiosis, or syntrophy, mediated by hydrogen or electron transfer between archaea and bacteria. However, unlike the original hydrogen and syntrophy hypotheses, which proposed interspecies hydrogen transfer from the bacterial to the archaeal symbiont, the ‘reverse flow model’ involves electron or hydrogen flow from the archaeal to the bacterial symbiont. This eukaryogenetic syntrophy likely established in anoxic or microoxic environments8,9. Although the model specifically involves one archaeon and one bacterium, Spang et al.8 leave open the possibility that symbiotic interactions with other prokaryotes might have intervened, in consonance with recent proposals for serial symbioses11.

This is exactly what Spang et al.8 and Bulzu et al.9 have done by reconstructing the metabolism of various Asgard archaeal lineages from metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) mostly from sediments. Asgard archaea exhibit high metabolic versatility. Loki- and Thorarchaeota likely fix carbon using the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (WLP) and can derive electrons from diverse organic substrates, including complex carbohydrates, fatty acids, amino acids, peptides and alcohols. Lokiarchaeota also seem to have a reverse tricarboxylic acid cycle9. Although they might be able to grow lithoautotrophically on H2, Loki- and Thorarchaeota likely use it to reduce CO2. They can also use formate as carbon or energy source. Loki- and Thorarchaeaota can link the oxidation of organics to the generation of membrane potential and produce hydrogen from fermentation. Thus, depending on environmental conditions, they can either consume or produce hydrogen and, if strong electron acceptors are lacking, as very often in anoxic sediments, they might engage in syntrophic interactions with hydrogen or formate scavengers. The presence of reductive dehalogenases additionally suggest that they can also shuttle electrons to organohalide compounds. However, whereas Lokiarchaeota use WLP in reverse to oxidize organics, Thorarchaeota possess a canonical respiratory chain complex I coupling the respiration of organics to the generation of an electrochemical gradient8. The thermophilic Odinarchaeota are able to ferment organics and can couple ferredoxin oxidation to respiratory H+ reduction.

While Loki-, Thor- and Odinarchaeota possess metabolisms typically associated with anoxic environments, Heimdallarchaeota, which seem so far the closest known archaeal lineage to eukaryotes, are somewhat different. They have also flexible metabolism and, like Odinarchaeota, some Heimdallarchaeota can ferment and couple ferredoxin oxidation to a respiratory chain for H+ reduction. Likewise, some can use organohalides as electron acceptors. Others use hydrocarbons as substrate. However, unlike the rest of their known Asgard relatives, some Heimdallarchaeota show a more oxygen-dependent metabolism, likely oxidizing organics using nitrate or oxygen as terminal electron acceptors. Furthermore, they contain the oxygen-dependent kynurenine pathway for NAD+ biosynthesis that is widespread in eukaryotes, which they likely imported horizontally from bacteria9. In addition, Bulzu et al.9 identify the presence of several rhodopsins in Heimdallarchaeota, including putative type-1 proton pumps, the functionally enigmatic heliorhodopsins and a new family of rhodopsins discovered also in Loki- and Thorarchaeota, the schizorhodopsins. This suggests exposure to light and habitat linked to sediment surface.

These observations lead Bulzu et al.9 to propose the ‘aerobic protoeukaryote’ model, stating that both symbiotic partners at the origin of eukaryotes, the bacterium and the archaeon, used oxygen for respiration in a microoxic niche without nonetheless advancing any specific metabolic (or other) interaction underlying the eukaryogenetic symbiosis. Inferring a fully aerobic metabolism for the archaeal partner may be premature. Not all Heimdallarchaeota are aerobic, oxygen and nitrate respiration having been imported from bacteria at a relatively later stage difficult to date8,9. In addition, our knowledge of archaeal diversity remains partial, as reveals the recent identification of a new Asgard lineage, the Helarchaeota, which anaerobically oxidize short-chain hydrocarbons10. It is therefore possible that other archaeal lineages even more closely related to eukaryotes exist. Indeed, one should always bear in mind the limits of actualism when trying to infer past metabolisms from modern organisms occupying a few terminal branches in phylogenetic trees. From this perspective, the inference of ancestral metabolism by a relaxed common denominator approach combined with phylogenetic information seems safer. Spang et al.8 thus conclude that the last Asgard common ancestor thrived in anoxic environments, possessed the WLP, had the ability to use various organics, likely including fatty acids, and lacked terminal reductases for exogenous electron acceptors. It also had the capacity to either produce or consume hydrogen depending on the environmental conditions.

Based on this primeval metabolic potential and on the fact that syntrophic interactions are widespread in anoxic environments3, Spang et al. propose the ‘reverse flow model’8, stating that the eukaryogenetic symbiosis involved the transfer of electrons or hydrogen from one Asgard archaeon to the alphaproteobacterial ancestor of mitochondria. Although these authors invoke only one bacterium, they also leave open the possible involvement of additional symbiotic partners8, as in recent suggestions of serial prokaryotic symbioses predating the mitochondrial acquisition11. Likewise, although Spang et al. favour an archaeon-to-bacterium flow of reducing equivalents, they do not discard the opposite flow, as proposed by the original hydrogen and syntrophy hypotheses, since Asgard archaea can be hydrogenogenic or hydrogenotrophic. The specific involvement of methanogens made the hydrogen and syntrophy hypotheses less supported when Asgard archaea were discovered, since methanogens were only known within Euryarchaeota. The hydrogen hypothesis was updated to suggest that the archaeon might have been a non-methanogenic hydrogen-dependent autotroph12. However, although Asgard archaeal methanogens are not known, hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis has been discovered in other deeply branching archaeal phyla13, suggesting that methanogenesis and possibly short-alkane-based metabolism14 might have been ancestral in archaea. Whatever the directionality, the chances for eukaryotes to derive from a metabolic symbiosis involving electron or hydrogen transfer, as suggested long ago7, are becoming increasingly high. From this perspective, the reverse flow model adds fresh air to the field of eukaryogenesis. Future studies providing more informed comparative genomic evidence for early archaeal metabolism, as well as archaeal functional characterization and ecological interactions in anoxic and microoxic settings should help to constrain evolutionary models for the origin of eukaryotes.

References

- 1.Martin WF, Garg S, Zimorski V. Endosymbiotic theories for eukaryote origin. Phil Trans Royal Soc London B. 2015;370 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0330. 20140330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez-Garcia P, Moreira D. Open questions on the origin of eukaryotes. Trends Ecol Evol. 2015;30:697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez-Garcia P, Eme L, Moreira D. Symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution. J Theor Biol. 2017;434:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spang A, et al. Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nature. 2015;521:173–179. doi: 10.1038/nature14447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, et al. Asgard archaea illuminate the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity. Nature. 2017;541:353–358. doi: 10.1038/nature21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eme L, Spang A, Lombard J, Stairs CW, Ettema TJG. Archaea and the origin of eukaryotes. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2017;15:711–723. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.López-García P, Moreira D. Metabolic symbiosis at the origin of eukaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:88–93. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spang A, et al. Proposal of the reverse flow model for the origin of the eukaryotic cell based on comparative analyses of Asgard archaeal metabolism. Nat Microbiol. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0404-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulzu PA, et al. Casting light on Asgardarchaeota metabolism in a sunlit microoxic niche. Nat Microbiol. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0404-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seitz KW, et al. Asgard archaea capable of anaerobic hydrocarbon cycling. Nature communications. 2019;10:1822. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09364-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pittis AA, Gabaldon T. Late acquisition of mitochondria by a host with chimaeric prokaryotic ancestry. Nature. 2016;531:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature16941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sousa FL, Neukirchen S, Allen JF, Lane N, Martin WF. Lokiarchaeon is hydrogen dependent. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.34. 16034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berghuis BA, et al. Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis in archaeal phylum Verstraetearchaeota reveals the shared ancestry of all methanogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:5037–5044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815631116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans PN, et al. An evolving view of methane metabolism in the Archaea. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2019;17:219–232. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]