Dairy Foods, Obesity, and Metabolic Health: The Role of the Food Matrix Compared with Single Nutrients (original) (raw)

ABSTRACT

In the 20th century, scientific and geopolitical events led to the concept of food as a delivery system for calories and specific isolated nutrients. As a result, conventional dietary guidelines have focused on individual nutrients to maintain health and prevent disease. For dairy foods, this has led to general dietary recommendations to consume 2–3 daily servings of reduced-fat dairy foods, without regard to type (e.g., yogurt, cheese, milk), largely based on theorized benefits of isolated nutrients for bone health (e.g., calcium, vitamin D) and theorized harms of isolated nutrients for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and obesity (e.g., total fat, saturated fat, total calories). However, advances in nutrition science have demonstrated that foods represent complex matrices of nutrients, minerals, bioactives, food structures, and other factors (e.g., phoshopholipids, prebiotics, probiotics) with correspondingly complex effects on health and disease. The present evidence suggests that whole-fat dairy foods do not cause weight gain, that overall dairy consumption increases lean body mass and reduces body fat, that yogurt consumption and probiotics reduce weight gain, that fermented dairy consumption including cheese is linked to lower CVD risk, and that yogurt, cheese, and even dairy fat may protect against type 2 diabetes. Based on the current science, dairy consumption is part of a healthy diet, without strong evidence to favor reduced-fat products; while intakes of probiotic-containing unsweetened and fermented dairy products such as yogurt and cheese appear especially beneficial.

Keywords: dietary guidelines, dairy, calories, vitamins, weight loss, probiotics, microbiome

Introduction

Conventional dietary guidelines from around the globe have focused on individual nutrients to maintain and improve health and prevent disease. This is due to the historical focus, developed in the last century, on single nutrients in relation to clinical nutrient deficiency diseases. However, this reductionist approach is inappropriate for translation to chronic diseases.

A look back at the history of modern nutrition science provides important perspectives on the origins of the reductionist approach to nutrition (1). In 1747, the British sailor and physician James Lind tested whether citrus fruits prevented scurvy, but it was not until 1932 that vitamin C was actually isolated, synthesized, and proven to be the relevant ingredient. The period of the 1930s to 1950s was a golden era of vitamin discovery, when all the major vitamins were identified, isolated, and synthesized, and shown to be the active constituents of foods relevant for nutrient deficiency diseases such as pellagra (niacin), beriberi (thiamine), rickets (vitamin D), and night blindness (vitamin A). This scientific focus on nutrient deficiencies coincided with global geopolitics, in particular the Great Depression and World War II, which accentuated concerns about insufficient food and nutrients. For example, the birth of RDAs was at the National Nutrition Conference on Defense in 1941, which focused on identifying the individual nutrients needed to prevent nutrient deficiencies in order to have a population ready for war. Together, these scientific and historical events led to the concept of food as a delivery system for calories and specific isolated nutrients (Figure 1).

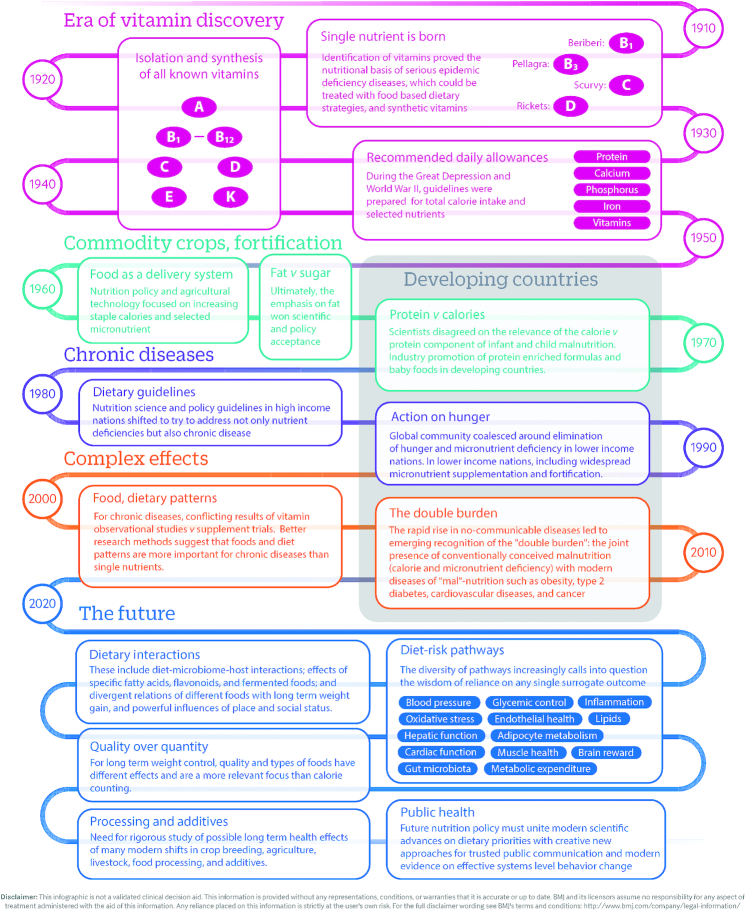

FIGURE 1.

Why our infatuation with single nutrients? Although food and nutrition have been studied for centuries, modern nutritional science is surprisingly young. This timeline shows how scientific and geopolitical developments in the early 20th century together helped shape our understanding and led to a reductionist notion of food as a delivery vehicle for total calories and isolated nutrients. Adapted from reference 1 with permission (open access).

It was not until the 1980s that modern nutrition science began to meaningfully consider nutrition in association with chronic diseases, such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and cancer. Intuitively, the reductionist paradigm that had been so successful in reducing the prevalence of nutrient deficiency diseases was extended to chronic diseases. Thus, saturated fat became “the” cause of heart disease, whereas now, excess calories and fat are “the” causes of obesity.

What recent advances in nutrition science have demonstrated, however, is that although a single-nutrient focus works well for prevention of deficiency diseases, such as scurvy or beriberi, this approach generally fails for chronic diseases such as coronary artery disease (CAD), stroke, type 2 diabetes, or obesity. For such complex conditions, the focus should be on foods.

Calories in/Calories out

The US obesity epidemic is a recent phenomenon, starting in the mid-1980s, and the rise of obesity globally is even more recent. The strategies to address this epidemic have not yet caught up with advances in nutrition science. Most current dietary recommendations and policies across the globe remain calorie and fat focused, recommending foods based on these reductionist metrics rather than their complex, empirically determined effects on health. For example, nearly all guidelines recommend low-fat or nonfat dairy foods to reduce calories, total fat, and saturated fat in the diet, based on the theory that this will help maintain a healthy weight and reduce the risk of CVD. This is seen, for example, in the 2015–2020 US Dietary Guidelines (2, 3); National School Lunch Program, NIH Dietary Guidelines for Kids (4); and CDC Diabetes Prevention Program (5).

However, foods are not simply a collection of individual components, such as fat and calories, but complex matrices that have correspondingly complex effects on health and disease. Recommendations based on calorie or fat contents fail to consider the complex effects of different foods, independent of their calories, on the body's multiple, redundant mechanisms for weight control, from the brain to the liver, the microbiome, and hormonal and metabolic responses. This growing evidence indicates that different foods, calorie-for-calorie, have different effects on the risk of long-term weight gain and success of weight maintenance (6–12).

Dairy Foods and Weight

Although dairy products contribute ∼10% of all calories in the US diet, until recently, little direct research had evaluated the health effects of different dairy foods. The complex ingredients and matrices of different dairy foods, from milk to yogurt to cheese, appear to have varying effects on weight.

Although considerable research has focused on optimal diets for weight loss among obese individuals (secondary prevention), fewer studies have evaluated determinants of gradual weight gain (primary prevention). Among nonobese US adults, the average weight gain is ∼1 lb (0.45 kg) per year. This represents a very slow, modest increment, but when sustained over many years, this small annual weight gain drives the obesity epidemic. This gradual pace also makes it difficult, if not impossible, for individuals to identify specific causes or remedies.

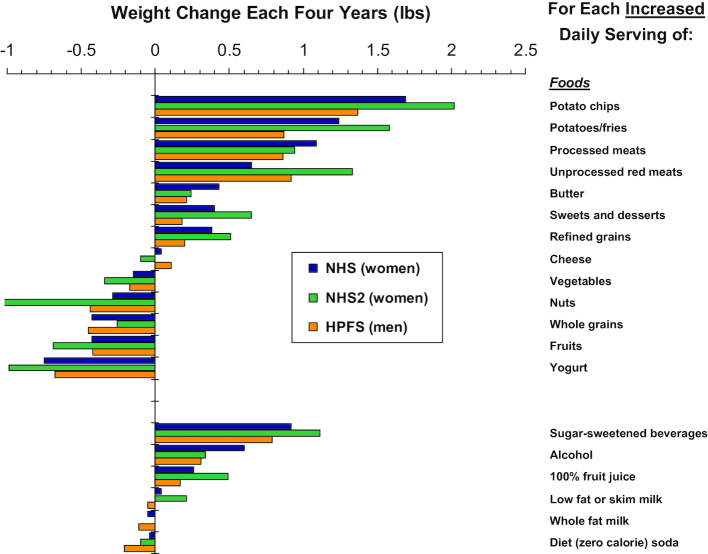

To identify specific dietary factors associated with long-term weight gain, we performed prospective investigations among 3 separate cohorts that included 120,877 US men and women who were free of chronic disease and not obese at baseline (Figure 2) (13). We examined weight gain every 4 y, for up to 24 y of follow-up, and its association with the increased intake of individual foods. Within each 4-y period, participants gained an average of 3.35 lb. On the basis of increased daily servings of different foods, those strongly linked to weight gain were generally carbohydrate-rich, including potato chips (per daily serving, 1.69 lb greater weight gain every 4 y), other potatoes/fries (1.28 lb), sugar-sweetened beverages (1.00 lb), sweets (0.65 lb), and refined grains (0.56 lb). Other foods were not linked to weight gain, even when their intake was increased, including cheese, low-fat milk, and whole milk. Other foods were actually related to less weight gain: the more they were consumed, the less weight was gained. This included vegetables (−0.22 lb), whole grains (−0.37 lb), fruits (−0.49 lb), nuts (−0.57 lb), and yogurt (−0.82 lb). When sweetened vs. plain yogurt were evaluated, each was associated with relative weight loss, although when sweetened, about half the benefit was lost.

FIGURE 2.

Association of different foods and beverages with long-term weight gain or loss. Among 120,877 US adults in 3 separate cohorts followed for up to 24 y, with time-varying multivariable adjustment for age, sex, baseline BMI, sleep duration, smoking, physical activity, television watching, and all dietary factors jointly. HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-Up Study; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; NHS2, Nurses’ Health Study 2. Adapted from reference 13 with permission.

What could explain these findings? We hypothesize that different foods have varying effects on multiple redundant mechanisms for weight gain, including effects on hunger and fullness; glucose, insulin and other hormonal responses; de novo fat synthesis by the liver; gut microbiome responses; and the body's metabolic rate.

Based on these findings, certain foods, when consumed over the long term can have relatively neutral effects on weight, others promote weight gain, whereas still others promote weight loss.

Interestingly, although we found that cheese, low-fat milk, and whole-fat milk were each unassociated with weight change, there is evidence that dairy foods may promote healthier body composition. Consistent with our findings, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 37 randomized clinical trials with 184,802 participants, which assessed the effect of dairy consumption on weight and body composition, found that overall, dairy consumption had little effect on BMI. Body composition, however, changed significantly (14). Dairy consumption led to a reduction in fat mass (0.23 kg) and an increase in lean body mass (0.37 kg). Overall, high-dairy intervention increased body weight (0.01, 95% CI: −0.25, 0.26) and lean mass (0.37, 95% CI: 0.11, 0.62); decreased body fat (−0.23, 95% CI: −0.48, 0.02) and waist circumference (−1.37, 95% CI: −2.28, −0.46).

In subgroup analyses, such effects appeared larger in trials also having energy restriction, but such subgroup findings should be interpreted cautiously. The types and frequency of dairy products consumed varied among these trials, making it difficult to make distinctions in this meta-analysis about the effects of different types of dairy products such as low-fat or whole fat, or milk, yogurt, or cheese. When viewed in combination with our long-term observational findings, the joint results suggest that dairy foods do not promote weight gain, that dairy consumption may reduce body fat and augment muscle mass, and that the type of dairy product (milk compared with cheese compared with yogurt) may be more important for preventing long-term weight gain than the dairy fat content.

Dairy Foods, Probiotics, and the Microbiome

Many pathways appear relevant to the concept that foods cannot be judged on calorie content alone for risk of obesity. Among these, the gut microbiome is particularly interesting. Substantial evidence demonstrates that the quality of the diet strongly influences the gut microbiome (15). Among different factors, probiotics have been studied for their effect on the microbiome; as well as potential benefits of fermented foods; which may be greater than the sum of their individual microbial, nutritive, or bioactive components (15–17).

For example, in an experimental model (9), mice genetically predisposed to obesity were provided control diets or a “fast-food” chow with and without probiotic-containing yogurt or a single probiotic (Lactobacillus reuteri) in water. Without probiotics, mice on the fast-food chow gained significant weight. However, the addition of either probiotic-containing yogurt or water prevented this weight gain. Crucially, the probiotics did not appear to reduce the amount of calories consumed; rather, the benefits appeared related to changes in microbiome function and inflammatory pathways. The results support weight benefits of probiotics and, more importantly, provide empiric evidence that challenges the widely accepted conventional wisdom that the effects of different foods on obesity depend largely on their calories.

Consistent with this animal experiment, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials examined the effects of probiotics, either in foods or as supplements, on body weight and composition in overweight and obese subjects (18). Administration of probiotics significantly reduced body weight (−0.60 kg), BMI (−0.27 kg/m2), and fat percentage (0.60%), compared with placebo. A separate meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials demonstrated that consumption of probiotics in foods or supplements significantly improves blood glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance (19). The trials in these two meta-analyses were neither long-term nor large—in all, a total of about 1,000 subjects were included in each meta-analysis, with trial durations ranging from 3 to 24 wk and with varying designs in terms of controls, disease conditions, and composition of probiotic preparations evaluated. Nonetheless, together with observational and experimental evidence, these studies provide compelling evidence to support weight and metabolic benefits of foods rich in probiotics.

Dairy Foods, CVD, and Diabetes

Although an important risk factor for type 2 diabetes and CVD, growing research suggests that specific foods may also directly alter disease risk. In a meta-analysis of 29 prospective cohort studies including 938,465 participants who experienced 93,158 deaths, 28,419 incident CAD events, and 25,416 incident CVD events, neither total dairy nor milk consumption was significantly associated with total mortality, CAD, or CVD (20). Notably, findings were similar when total whole-fat dairy, or low-fat dairy were separately evaluated. In contrast, the intake of fermented dairy products (predominantly cheese, plus yogurt and fermented milk) was associated with modestly lower risk of total mortality and CVD, with about 5% lower risk of each per 50 g daily serving. In addition, the consumption of cheese alone, the dairy product with the highest amount of dairy fat, was associated with a significantly lower risk of both CAD and stroke (20).

In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis cohort, including 5209US adults with Caucasian, Asian, black, and Hispanic backgrounds, different food sources of saturated fat were analyzed for their relation with subsequent CVD risk, adjusted for sociodemographics, medical history, and other dietary and lifestyle factors (21). A higher intake of saturated fat from dairy sources was associated with significantly lower CVD risk (per each 5 g/d, RR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.68, 0.92), whereas a higher intake of saturated fat from meat sources was associated with higher CVD risk (per each 5 g/d, RR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.54). Intakes of saturated fat from other sources, such as butter and plant oils/foods, were too low to identify any associations.

These findings suggest that saturated fat from different food sources may have varying effects on CVD risk. This may partly relate, for example, to differences in the types of saturated fatty acids in meat compared with dairy. Compared with meat, dairy has a greater proportion of short-chain and medium-chain saturated fatty acids, with correspondingly less palmitic and stearic acids (22). Compared with their longer chain fatty acids, growing evidence suggests that shorter and medium-chain triglycerides have different physiology, including potential benefits on metabolic risk, weight gain, obesity, and the gut microbiome (23, 24).

In addition, cardiometabolic effects of different dairy foods appear to vary depending on other characteristics, such as fermentation or the presence of probiotics. The large European Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort across 8 European countries evaluated the consumption of different dairy foods and risk of diabetes among 340,234 participants with 12,403 new cases of diabetes during follow-up. In the fully adjusted model including adjustment for estimated dietary calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D, the consumption of milk (low-fat and whole-fat) was not significantly associated with type 2 diabetes. Individuals who consumed more yogurt or thick fermented milk experienced a nonsignificant trend toward lower risk (across quintiles: RR = 0.89, 95% CI = 0.77, 1.03; _P_-trend = 0.11), whereas individuals who consumed more cheese had significantly lower risk of diabetes (RR = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.70, 0.98; _P_-trend = 0.003) (25). A higher combined intake of fermented dairy products (cheese, yogurt, and thick fermented milk) was also associated with a lower risk of diabetes (RR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.73, 0.99; _P_-trend = 0.02).

Similarly, in the Malmö Diet and Cancer Cohort following 26,930 participants over 14 y, different food sources of fat and saturated fat had very different associations with incidence of diabetes (26). Overall, low-fat dairy consumption was associated with a higher risk of diabetes (across quintiles: RR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.28; _P_-trend = 0.01), whereas whole-fat dairy consumption was associated with a substantially lower risk RR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.68, 0.87; _P_-trend < 0.001). However, relations varied further by subtype. For example, nonfermented, low-fat milk was associated with higher risk; nonfermented, whole-fat milk was not associated with risk; and fermented, whole-fat milk was associated with lower risk. Cheese intake showed a nonsignificant trend toward lower risk (RR = 0.92, 95% CI = 0.81, 1.04; _P_-trend = 0.21), whereas red meat intake was associated with significantly higher risk (RR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.20, 1.55; _P_-trend < 0.001). When estimated intakes of individual fatty acids were evaluated, intakes of saturated fatty acids with 4–10 carbons, lauric acid (12:0), and myristic acid (14:0) were associated with decreased risk (_P_-trend = 0.01).

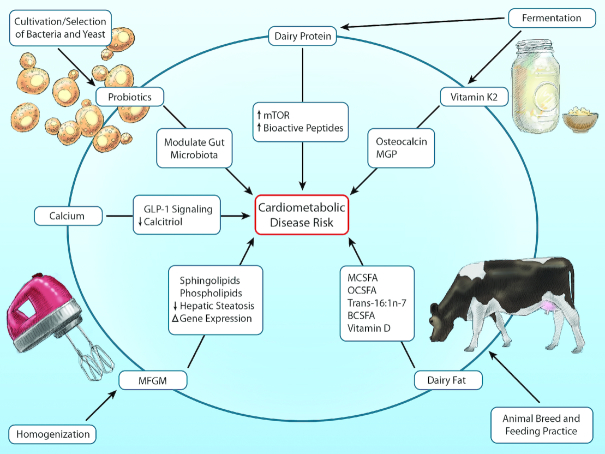

In addition to the consumption of whole foods such as milk, cheese, or yogurt, significant amounts of dairy fat can be consumed as relatively “hidden” ingredients in creams, sauces, cooking fats, bakery desserts, and mixed dishes such as casseroles containing butter, milk, or cheese. Self-reported questionnaires may miss many of these sources, leading to inaccurate measurement of true dairy fat consumption in individuals. Biomarkers can partly reduce this mismeasurement. In a global consortium combining de novo individual-level analyses across 63,602 participants in 16 separate cohort studies, higher blood concentrations of odd-chain saturated fatty acids (15:0, 17:0) and a natural ruminant trans fatty acid (_trans_-16:1n–7), objective circulating biomarkers of dairy fat consumption, were evaluated in relation to onset of diabetes (27). Each fatty acid was associated with lower incidence of diabetes, with ∼20–35% lower risk across the interquintile range of blood concentrations. It is unclear whether such lower risk is related to direct health benefits of specific dairy fatty acids, or to other aspects of foods rich in dairy fat. For example, the major source of dairy fat in most diets is cheese, a fermented food rich in vitamin K2 (menoquinone) which is converted from vitamin K by the action of bacteria. Menoquinone, which cannot be separately synthesized by humans, is linked to lower risk of type 2 diabetes in prospective observational studies, with supportive experimental evidence for potential benefits on glucose control and insulin sensitivity (28). The biologic mechanisms that could explain metabolic and diabetes benefits of dairy foods and dairy fat have been recently reviewed (27) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Relevant characteristics of dairy foods and selected molecular pathways potentially linked to cardiometabolic disease. Dairy foods are characterized by a complex variety of nutrients and processing methods that may influence cardiovascular and metabolic pathways. Examples of relevant constituents include specific fatty acids, calcium, and probiotics. Relevant processing methods may include animal breeding and feeding, fermentation, selection and cultivation of bacterial and yeast strains (e.g., as fermentation starters), and homogenization. Such modifications can alter the composition of the food (e.g., fermentation leads to production of vitamin K2 from vitamin K1) and its lipid structures (e.g., homogenization damages milk fat globule membrane), each of which can affect downstream molecular and signaling pathways. BCSFA, branched-chain saturated fats; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; MCSFA, medium-chain saturated fats; MFGM, milk fat globule membrane; MGP, matrix glutamate protein; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; OCSFA, odd-chain saturated fats. Reproduced from reference 27 with permission.

Based on all the evidence, the relation of dairy foods to obesity, CVD, and diabetes does not consistently differ by fat content, but rather appears to be more specific to food type. In particular, neither low-fat nor whole milk appear strongly related to either risks or benefits, whereas cheese and yogurt (as well as other fermented dairy such as fermented milk) may each be beneficial. These findings suggest that health effects of dairy may depend on multiple complex characteristics, such as probiotics, fermentation, and processing, including homogenization and the presence or absence of milk fat globule membrane (29).

Holistic Dietary Recommendations

Conventional dietary guidelines generally recommend 2–3 daily servings of low-fat or nonfat dairy foods, without regard of type (yogurt, cheese, milk); largely based on theorized benefits of isolated nutrients for bone health (e.g., calcium, vitamin D) and theorized harms of isolated nutrients for obesity and CAD (e.g., total fat, saturated fat, total calories). Advances in science indicate that updated dietary guidelines must incorporate the empirical evidence on health effects of different dairy products on weight, body composition, CVDs, and diabetes. These findings suggest that recommendations for milk, cheese, and yogurt should be considered separately, based on their differing relations with clinical outcomes. These findings further suggest that whole-fat dairy foods do not cause weight gain; that overall dairy consumption increases lean body mass and reduces body fat; that yogurt consumption and probiotics reduce weight gain; that fermented dairy consumption including cheese is linked to lower CVD risk; and that yogurt, cheese, and even dairy fat may protect against type 2 diabetes.

Based on the current science, dairy consumption is part of a healthy diet, and intakes of probiotic-containing yogurt and fermented dairy products such as cheese should be especially encouraged. Based on little empiric evidence that low-fat dairy products are better for health, and at least emerging research suggesting potential benefits of foods rich in dairy fat, the choice between low-fat compared with whole-fat dairy should be left to personal preference, pending further research. Such recommendations are consistent with a growing focus on and understanding of the importance of foods and overall diet patterns, rather than single isolated nutrients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author has read and approved the final manuscript. A freelance writer, Denise Webb, PhD, prepared an initial draft of this manuscript for DM based on a recording of his talk and slides at the 6th annual Yogurt in Nutrition Summit in Boston, MA.

Notes

This article appears as part of the supplement "Yogurt, more than the sum of its parts—6th Global Summit on the Health Effects of Yogurt Proceedings" sponsored by Danone Institute International. The guest editor of the supplement has the following conflict of interest: Sharon Donovan co-chairs the Yogurt in Nutrition Initiative. She received reimbursement for travel expenses and an honorarium from Danone Institute International for chairing the 6th International Yogurt in Nutrition Summit at the Nutrition 2018 meeting in June 2018 in Boston, MA. Publication costs for this supplement were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and are not attributable to the sponsors or the publisher, Editor, or Editorial Board of Advances in Nutrition.

This manuscript is based upon an invited scientific talk presented at the American Society of Nutrition 2018 Congress, Boston, MA.

DM received an honorarium from the American Society of Nutrition for the preparation of this manuscript. A freelance science writer, Denise Webb, was supported by Danone Institute International to prepare an initial draft of this manuscript for DM based on a recording of his talk and slides at the American Society of Nutrition 2018 Congress. The final manuscript was edited in detail and approved by DM. The funders had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, review, or final approval of the manuscript for publication.

Author disclosures: DM reports research funding from the NIH and the Gates Foundation; personal fees from GOED, Nutrition Impact, Pollock Communications, Bunge, Indigo Agriculture, Amarin, Acasti Pharma, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, and America's Test Kitchen; scientific advisory board, Elysium Health (with stock options), Omada Health, and DayTwo; and chapter royalties from UpToDate; all outside the submitted work.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Rosenberg I, Uauy R. History of modern nutrition science—implications for current research, dietary guidelines, and food policy. BMJ. 2018;361:k2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th ed., December2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nutrition Standards in the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs. Vol. 77 Fed Reg. 7 CFR Parts 210 and 220 (final rule 26 January 2012). [PubMed]

- 4.US Department of Health & Human Services. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Choosing foods for your family 2013. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/wecan/eat-right/choosing-food.htm (Accessed 2018 Dec 3). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Participant guide to prevent T2. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/preventon/pdf/t2/Participant-Module-4_Eat-Well_to_Prevent_T2.pdf (Accessed 2018 Dec 3). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation. 2016;133(2):187–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Browning JD, Baker JA, Rogers T, Davis J, Satapati S, Burgess SC. Short-term weight loss and hepatic triglyceride reduction: evidence of a metabolic advantage with dietary carbohydrate restriction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(5):1048–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebbeling CB, Swain JF, Feldman HA, Wong WW, Hachey DL, Garcia-Lago E, Ludwig DS. Effects of dietary composition on energy expenditure during weight-loss maintenance. JAMA. 2012;307(24):2627–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poutahidis T, Kleinewietfeld M, Smillie C, Levkovich T, Perrotta A, Bhela S, Varian BJ, Ibrahim YM, Lakritz JR, Kearney SM et al.. Microbial reprogramming inhibits Western diet-associated obesity. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e68596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lennerz BS, Alsop DC, Holsen LM, Stern E, Rojas R, Ebbeling CB, Goldstein JM, Ludwig DS. Effects of dietary glycemic index on brain regions related to reward and craving in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:641–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludwig DS, Friedman MI. Increasing adiposity: consequence or cause of overeating?. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2167–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Klein GL, Wong JM, Bielak L, Steltz SK, Luoto PK, Wolfe RR, Wong WW, Ludwig DS. Effects of a low carbohydrate diet on energy expenditure during weight loss maintenance: randomized trial. BMJ. 2018;363:k4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geng T, Qi L, Huang T. Effects of dairy products consumption on body weight and body composition among adults: an updated meta-analysis of 37 randomized controlled trials. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018:62(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonnenburg JL, Backhed F.. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature. 2016;535:56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marco ML, Heeney D, Binda S, Cifelli CJ, Cotter PD, Foligne B, Ganzle M, Kort R, Pasin G, Pihlanto A et al.. Health benefits of fermented foods: microbiota and beyond. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2017;44:94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1027–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borgeraas H, Johnson LK, Skattebu J, Hertel JK, Hjelmesaeth J. Effects of probiotics on body weight, body mass index, fat mass and fat percentage in subjects with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2018;19(2):219–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruan Y, Sun J, He J, Chen F, Chen R, Chen H. Effect of probiotics on glycemic control: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo J, Astrup A, Lovegrove JA, Gijsbers L, Givens DL, Soedamah-Muthu SS. Milk and dairy consumption and risk of cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:269–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otto MC, Mozaffarian D, Kromhout D, Bertoni AG, Sibley CT, Jacobs DR Jr, Nettleton JA. Dietary intake of saturated fat by food source and incident cardiovascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28 (Slightly revised). Version Current: May2016. Internet: http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl 22. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rial SA, Karelis AD, Bergeron KF, Mounier C. Gut microbiota and metabolic health: the potential beneficial effects of a medium chain triglyceride diet in obese individuals. Nutrients. 2016;8:e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhavsar N, St-Onge MP.. The diverse nature of saturated fats and the case of medium-chain triglycerides: how one recommendation may not fit all. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19(2):81–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sluijs I, Forouhi NG, Beulens JWJ, van der Schouw YT, Agnoli C, Arriola L, Balkau B, Barricarte A, Boeing H, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB. The amount and type of dairy product intake and incident type 2 diabetes: results from the EPIC-Interact Study. 2012;96:382–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ericson U, Hellstrand S, Brunkwall L, Schulz CA, Sonestedt E, Wallstrom P, Gullberg B, Wirfalt E, Orho-Melander M. Food sources of fat may clarify the inconsistent role of dietary fat intake for incidence of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(5):1065–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mozaffarian D, Wu JHY. Flavonoids, dairy foods, and cardiovascular and metabolic health: a review of emerging biologic pathways. Circ Res. 2018;122(2):369–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Chen JP, Duan L, Li S. Effect of vitamin K2 on type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Diab Res Clin Prac. 2018;136:39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosqvist F, Smedman A, Lindmark-Mansson H, Paulsson M, Petrus P, Straniero S, Rudling M, Dahlman I, Riserus U. Potential role of milk fat globule membrane in modulating plasma lipoproteins, gene expression, and cholesterol metabolism in humans: a randomized study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(1):20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]