Kids these days: Why the youth of today seem lacking (original) (raw)

We view kids these days unfavorably, especially on traits at which we excel, partly because we have a biased view of the past.

Abstract

In five preregistered studies, we assess people’s tendency to believe “kids these days” are deficient relative to those of previous generations. Across three traits, American adults (_N_=3,458; _M_age = 33-51 years) believe today’s youth are in decline; however, these perceptions are associated with people’s standing on those traits. Authoritarian people especially think youth are less respectful of their elders, intelligent people especially think youth are less intelligent, well-read people especially think youth enjoy reading less. These beliefs are not predicted by irrelevant traits. Two mechanisms contribute to humanity’s perennial tendency to denigrate kids: (1) a person-specific tendency to notice the limitations of others where one excels, (ii) a memory bias projecting one’s current qualities onto the youth of the past. When observing current children, we compare our biased memory to the present and a decline appears. This may explain why the kids these days effect has been happening for millennia.

INTRODUCTION

Youth were never more sawcie… the ancient are scorned, the honourable are contemned, the magistrate is not dreaded.—Thomas Barnes, the minister of St. Margaret’s Church on New Fish Street in London, 1624 (1)

Since at least 624 BCE, people have lamented the decline of the present generation of youth relative to earlier generations (2–5). The pervasiveness of complaints about “kids these days” across millennia suggests that these criticisms are neither accurate nor due to the idiosyncrasies of a particular culture or time—but rather represent a pervasive illusion of humanity. Given its potential ubiquity, surprisingly little research has investigated the extent or source of peoples’ disparaging the youth of the day. Nevertheless, various strands of investigations suggest mechanisms for this seeming illusion and make distinct predictions regarding how it may generalize across individuals and traits.

Some accounts predict that perceptions of the decline of youth should be person general, largely independent of an individual’s own qualities. People tend to view themselves as superior to others across domains (6, 7) and often independently of their actual qualities (8). Accordingly, people’s disparaging the youth may result from viewing an aspect of themselves (and their generation) as superior to others (the present generation of youths). Given the generality of illusory superiority across individuals and traits, people should view their own generation as superior to that of the present across domains and independent of their own abilities.

Other accounts suggest that the tendency to disparage today’s youth may be person specific, critically depending on the evaluator’s own standing on the trait in question. Individuals who excel in a particular trait are likely to notice disparities between themselves and the youth of the present. Various factors, however, might bias their recollections of the way the youth of the past actually were, including memory biases (9, 10) and/or exposure to a more similar population of youth growing up (11). People’s perception of differences between themselves and the youth of the day (but not youth of the past) on qualities on which they excel may lead them to believe that children today are in decline. This view predicts that these perceptions should be particularly pronounced for dimensions on which people themselves excel.

Five studies were designed to examine the occurrence of and mechanisms underpinning people denigrating the youth of the present (herein termed the kids these days effect). Studies 1 to 3 examined the prevalence of the kids these days effect across three different traits and the degree to which it is pronounced for people who excel on that trait. Study 1 examined whether the belief that children are less respectful of their elders is magnified for people who are high in authoritarianism. Study 2 investigated whether people who are more intelligent are particularly predisposed to believe that children are becoming less intelligent. Study 3 explored whether well-read people are especially likely to think that today’s children no longer like to read. Then, study 4 investigated the mechanisms leading people to perceive kids these days as particularly lacking on those traits on which they themselves excel in a mediation model. Study 5 manipulated people’s beliefs in their standing in one of these domains and showed resulting indirect decreases in the kids these days effect through our proposed mechanisms. All studies were Institutional Review Board approved.

RESULTS

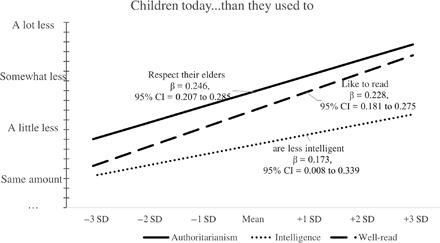

In study 1, we administered to 1824 Americans drawn to match the U.S. adult demographics from an online panel (CriticalMix) a measure of authoritarianism (12) and asked how much participants believed that children today respect their elders compared to when they were children. Average ratings were significantly above the mean, showing that, on average, people believed that children of today are less respectful of their elders than they used to be (intercept/summary mean: b = 0.503, SE = 0.112, P < 0.001). Furthermore, people who held a higher degree of respect for authority believed that children today respect their elders less [β = 0.265, _P_ < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.304 to 0.227]. In an exploratory analysis, we also found that older participants believed that kids these days are becoming less respectful of their elders (β = 0.161, _P_ < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.206 to 0.115), but no interaction between authoritarianism and age (_P_ > 0.56). Furthermore, conditioning on age, the authoritarianism effect still held (β = 0.246, P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.285 to 0.207). Last, modeling authoritarianism as a single latent factor (instead of the preregistered summary score) showed the same relationship where the more authoritarian someone is, the more they believe that children today no longer respect their elders (β = 0.293, P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.337 to 0.248).

In study 2, we examined whether the kids these days effect generalizes to perceptions about intelligence. This metric of attitudes toward children is especially noteworthy because, given the rising intelligence across the decades (13, 14), children today are more intelligent than children of the past, a trend continuing in the United States (15). We recruited a new sample of 134 participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk. We administered both the authoritarianism measure and an eight-item vocabulary measure constructed using Rasch modeling from the full 40-item vocabulary subscale of the Completion, Arithmetic, Vocabulary, and Directions (CAVD) intelligence test (16, 17). Unlike in the case of authoritarianism, the summary mean was no different from the belief of “no change in intelligence” (P > 0.81). More intelligent people, however, believed that children today were becoming less intelligent (β = 0.173, P = 0.036, 95% CI = 0.339 to 0.008). Adding authoritarianism to the model showed that authoritarianism was unrelated to these beliefs about children (β = −0.054, P > 0.49). This means that the results from study 1 were not simply the relationship of authoritarian beliefs predicting complaints about children or society in general [cf. (18)]. Instead, per our trait-specific hypothesis, the kids these days effect occurs in another domain and is stronger for only those who are higher in that domain.

In study 3, we examined the kids these days effect regarding beliefs about children’s enjoyment of reading. According to the trait-specific hypothesis, people who are more well read will be especially inclined to believe that “children of today don’t like to read.” To test this hypothesis, we recruited a new sample of 1500 adults drawn to match the national demographics as in study 1. Participants were asked to what extent they believe that children today enjoy reading compared to when they were a child. As an objective measure of how well-read participants were, we administered the Author Recognition Test (19, 20). We also measured participants’ political orientation for a more robust test of the domain specificity of our hypothesis—refuting the idea that only the politically conservative believe in the downfall of civilization. As with respect for elders, people believed that kids these days enjoyed reading less than they used to (intercept/summary mean: b = 1.189, SE = 0.114, P < 0.001). Furthermore, the more well-read people were, the more they believed that children today no longer like to read (β = 0.227, _P_ < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.274 to 0.179). Political conservativeness showed no relationship to beliefs that children do not like to read anymore (_P_ > 0.25). The relationship between how well-read people were and their beliefs in declining children remained significant, conditioning on conservativeness (β = 0.228, P < 0.001) and conservativeness and age (β = 0.201, P < 0.001).

In general, people endorsed the view that kids these days are in decline for two of the three traits (Fig. 1). That this was not, on average, present for intelligence suggests that the kids these days effect is not simply illusory superiority. Furthermore, what is particularly notable is the degree to which people’s belief that children are in decline was larger for people who excelled on the trait in question. This latter finding suggests the involvement of a person-specific self-comparison process whereby individuals compare themselves to today’s youth and find them especially lacking on those domains on which they themselves excel. This account, however, leaves open the question of why people fail to similarly denigrate the youth of the past. One possibility is biased memory; people routinely project their current selves onto their past selves (7)—such a memory bias may generalize to children of one’s own generation. Another possibility involves a biased sampling of the past youth that people consider in formulating their judgments. People may be accurately remembering the attributes of children in their past but the sample on which this judgment is based is biased toward a sample of peers who were similar to themselves.

Fig. 1. Results from studies 1 to 3 on Americans’ beliefs in the decline of children.

Straight line represents authoritarians believing that children no longer respect their elders. Dotted line represents more intelligent people believing that children are becoming less intelligent. Dashed line represents more well-read people believing that children no longer enjoy reading.

To explore these mechanisms underlying the kids these days effect, we replicated study 3—including subjective measures of how much people currently enjoy reading, how much they recall enjoying reading as a child, how much they recall their childhood friends enjoying reading, and how much they think adults today enjoy reading compared to adults of the past. These additional measures enabled us to build a mediation model to explore the direct and indirect effects of various factors contributing to the kids these days effect. If, as hypothesized, individuals with objectively elevated traits are especially prone to see others as lacking in that trait, then objective measures of being well read would predict people’s disparaging the reading inclinations of both kids and adult these days, while subjective measures, after conditioning on objective ability, would not. If, as the biased memory account predicts, the kids these days effect is a product of people’s memories of their own qualities as youth, then it should be mediated by self-reports of their recollections of how much they and their peers liked to read, remaining even when their attitudes about adults these days are accounted for. If, as the biased sampling account predicts, the kids these days effect results from a reliance on biased sampling from a peer set who were similar to themselves on the trait in question, there should be a positive relationship between their own objective abilities and their recollections of the ability of their peers.

The results replicated study 3’s finding that people who are well read are more likely to disparage today’s youth’s enjoyment of reading. The well read also disparaged other adults’ current enjoyment of reading. Notably, even when attitudes about the self and others growing up were concurrently partialed out, we still observed a relationship between objective measures of how well read someone is and beliefs that “adults these days” (β = 0.144, P < 0.001) and kids these days (β = 0.16, P < 0.001) no longer like to read. This finding supports the conjecture that people who are objectively elevated in a trait are particularly predisposed to notice others (both youth and adults) as lacking in that trait. Even when views about adults were accounted for, we still observed the predicted effect with youth, indicating that the kids these days effect is not just a general belief in societal decline [cf. (18)]. While people may believe in a general decline, they also believe that children are especially deficient on the traits in which they happen to excel.

Furthermore, participants overall believed that adults these days enjoy reading just as much as adults used to when they were a child. Responses of “the same amount” were coded as 4 in the adults these days scale, and the intercept is centered around that value (_b_intercept = 4.115, 95% CI = 4.384 to 3.837). This suggests that participants are not sensing a constant generational decline (e.g., we as kids were worse than our parents’ generation, who were worse than their parents’ generation, etc.) but instead believe that it is uniquely children today who are deficient. Yet again, the more well-read someone is, the more they believe that adults these days do not like to read as much as adults of the past.

The relationship between how well-read someone objectively is and their belief that children today no longer like to read was also mediated by how much they “remember” liking to read as a child (βobjective = 0.016, P < 0.002, 95% CI = 0.026 to 0.007). In support of the biased memory account, the relationship of subjective measures of how much one enjoys reading to one’s belief that children today no longer like to read was also mediated through one’s recollection of how much one enjoyed reading as a child (βsubjective = 0.097, P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.129 to 0.066). These analyses were run concurrently, accounting for the objective and subjective relationships simultaneously. Thus, we found evidence for our proposed mechanism that the domain-local kids these days effect is mediated by memories of the past.

Last, we found evidence against the biased sampling hypothesis—that the results are driven by participants’ accurate recollections of a similar nonrepresentative youth peer set. Specifically, the more objectively well-read someone was, partialing out subjective beliefs, the less they “recalled” their friends enjoying reading (β = −0.12, P < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.17 to −0.07). Instead, consistent with the biased-memory mechanism, partialing out objective measures of how well-read they were, the more someone says they enjoy reading now, the more they remember their childhood friends enjoyed reading (β = 0.289, P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.339 to 0.238). Thus, the peer “memories” do not track objective status but instead only subjective beliefs.

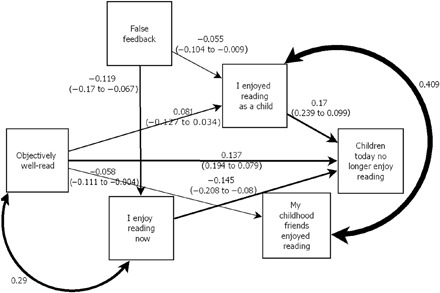

Study 5 put the mediation model to a causal test by experimentally influencing people’s perceptions of how well read they are. A new sample of 1500 American adults drawn to match the demographics of the U.S. were given a false feedback manipulation (21). After filling out the Author Recognition Test, participants were randomly told that they did very well (top 15% of the population) or very poorly (bottom 15% of the population). Afterward, they completed the same procedure as used in study 4 with the exclusion of the adults these days measure, as it was not part of the tested causal chain. The manipulation successfully changed participants’ subjective belief in how well read they are (β = −0.119, P < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.17 to −0.067), how much they recalled enjoying reading as a child (β = −0.055, _P =_ 0.022, 95% CI = −0.104 to −0.009), but not how much they recalled their peers enjoying reading (β = −0.023, _P_ > 0.39). Crucially, we observed the predicted indirect effect of reduced subjective beliefs in how well-read someone believes they are, causing a reduction in the kids these days effect through “memory” of how much one “recalls” enjoying reading as a child (β = −0.009, P = 0.04, 95% CI = −0.02 to −0.002). These results, conditioning on objective status, show that manipulating subjective beliefs causes an indirect reduction in the kids these days effect. Furthermore, there was no direct effect of the feedback manipulation on the kids these days effect not passing through a mediator (β = −0.023, P > 0.4). The absence of a direct effect of the false feedback manipulation on the kids these days effect argues against the possibility that it occurs because people subjectively high in a trait set higher standards (22–24). Instead, the fact that experimentally influencing people’s self-perceptions indirectly affects the kids these days effect through people’s altered recollections indicates that the effect is driven (at least in part) by people’s biased memory of themselves as children (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Mediation model from 1500 American adults drawn to match the demographics of the U.S. showing false feedback altering the kids these days effect indirectly through both subjective belief in reading ability (“I enjoy reading now”) and memory for how much one enjoyed reading as a child.

The crucial indirect pathway is manipulated beliefs in current ability altering the kids these days effect through reconstructed memory of how much one enjoyed reading as a child (β = −0.009, P = 0.04, 95% CI = −0.02 to −0.002).

DISCUSSION

In five studies, we found evidence of a general tendency to disparage the present youth across traits (respect for elders and enjoying reading) and a trait-specific tendency to see today’s youth as especially lacking on those traits on which one particularly excels (respect for elders, intelligence, and enjoying reading). Although the trait specificity of the kids these days effect was observed across three domains, there was no impact of excelling on a trait other than the one in question. Someone who has a high respect for authority is especially likely to believe that kids these days no longer respect their elders, but not necessarily that kids these days are in decline in other ways (e.g., becoming less intelligent). We also found indirect evidence for at least two mechanisms underpinning this effect. First, people who objectively excel in a dimension are more likely to notice others’ failings on that dimension, for both the youth and adults of the day. In addition, excelling on a dimension also leads people to project back to both themselves and their peers in the past, believing, for example, “because I like to read now everyone liked to read when I was a child.” Manipulating this subjective belief, partialing out objective standing, causes a reduction in the kids these days effect through this proposed mechanism. Apparently, when observing current children, we compare our biased memory of the past to a more objective assessment of the present, and a natural decline seems to appear. This can explain why the kids these days effect has been happening for millennia.

This backward projection from the self to kids likely occurs because people have fewer details available when recalling past peers than when assessing present adult peers. People use their present self as a proxy for their past self as well as projecting onto past others. When judging present others, we have readily available information and do not need to rely so much on self-projections. The causal effects shown in study 5, however, were small, suggesting additional mechanisms of the kids these days effect to those explored here.

The present findings suggest that denigrating today’s youth is a fundamental illusion grounded in several distinct cognitive mechanisms, including a specific bias to see others as lacking in those domains on which one excels and a memory bias projecting one’s current traits to past generations. It may be the case that, in some domains, children really have been in decline; in which case, our findings also highlight how accurate perceptions of declines relate to individuals’ standing on those traits. Although we cannot rule out actual declines, it is likely that part of the kids these days effect is illusory. In some domains (e.g., intelligence), children are increasing (13), and there is no objective reason more intelligent people would falsely believe the opposite. Although increases in intelligence have stalled in some countries, even reversing in some Nordic countries, in the United States, where these participants are from, intelligence continues to rise (15). Furthermore, in other domains (e.g., reading and respect for elders), the same complaints have been leveled against youth of the day for the past 2500 years; this would imply a steady deterioration over millennia, which seems highly unlikely. We find that perceptions of a decline in today’s youth can be experimentally manipulated by altering people’s memories of themselves as children. Although the cognitive mechanisms that unfairly impugn children today are likely to persist for millennia to come, knowledge of their sources may minimize unwarranted gloom about future generations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study 1

Participants were assigned to answer the “Kids These Days: Respect” scale and the authoritarianism scale in random order. The Kids These Days: Respect scale reads: “We would like to know your thoughts about how children of today respect their elders. Compared to when you were a child: Do you think children these days respect their elders more than they used to, less than they used to, or the same amount as they used to when you were a child?” Then, participants were asked their age. Using robust maximum likelihood estimation, we predicted a relationship between authoritarianism and belief that kids these days no longer respect their elders.

Study 2

Participants took the vocabulary test and the “Kids These Days: Intelligence” scales in random order. The Kids These Days: Intelligence scale reads: “We would like to know your thoughts about children’s intelligence. Compared to when you were a child: Do you think children today are more intelligent, less intelligent, or equally intelligent than they used to be?” For the vocabulary test, we chose an eight-item vocabulary measure constructed using item response theory (IRT) modeling from the full 40-item vocabulary subscale of the CAVD intelligence test. Matching the time-per-question rate on the full 40-item subtest, participants were given a total of 2 min to solve the eight items. Afterward, participants were given the authoritarianism scale. On the final page, participants were asked: “Have you ever heard of the Flynn effect?” and “Did you look up any of the words during the word definition part?” We predicted a relationship between intelligence and beliefs that kids these days are less intelligent than they used to be, with a residual relationship occurring with authoritarianism. As part of our preregistration, we removed any participant who had heard of the Flynn effect or admitted to looking up the answers.

Study 3

Participants filled out the Author Recognition Test and the “Kids These Days: Reading” scales in random order. The Author Recognition Test asked participants to indicate the number of authors that they recognize from a list of 20. Sixteen of these were real authors, and 4 were foils. The Kids These Days: Reading scale read: “We would like to know your thoughts about how children of today enjoy reading. Compared to when you were a child: Do you think children these days enjoy reading more than they used to, less than they used to, or the same amount as they used to when you were a child?” Participants were then asked to indicate their political orientation on an unnumbered scale (Very Conservative = 7, Conservative = 6, Somewhat Conservative = 5, Middle of the Road = 4, Somewhat Liberal = 3, Liberal = 2, Very Liberal = 1). The addition of ideology into the model was exploratory to test additional explanations.

Study 4

In this study, participants filled out the Author Recognition Test. Then, participants were asked three questions to assess our proposed mediators: “Now as an adult, how much do you enjoy reading?” “How much did you enjoy reading as a child?” “How much did your childhood friends enjoy reading when they were children?” Afterward, participants were asked a revised version of the Kids These Days: Reading scale: “We would like to know your thoughts about how children of today enjoy reading. Do you think children today enjoy reading more than they used to, less than they used to, or the same amount as they used to when you were a child?” Participants then filled out the Adults These Days: Reading scale, asking whether adults today enjoy reading more or less than they did in the participant’s birth year. Last, we asked participants their political orientation.

Study 5

First, participants provided their age and sex and indicated that they were ready to participate in the study. Next, participants filled out the Need for Achievement Scale for use as a potential moderator of the false feedback. Participants then filled out the Author Recognition Test. Afterward, participants read “Calculating test results - please wait.” on the screen for 8 s. Then, the next page automatically moved on to “Test Results: Click Next.” Here, participants were randomly assigned to the good or bad feedback groups. Participants in the good feedback group read: “Your performance on the author recognition test was measured as 35% above average. Thus, as an initial estimate, how well-read you are is ranked in the top 15% of the population.” Participants in the poor feedback group read: “Your performance on the author recognition test was measured as 35% below average. Thus, as an initial estimate, how well-read you are is ranked in the bottom 15% of the population.” All participants saw one of two graphics corresponding to either a good or poor performance, depending on their group. On the next page, participants were given the Kids These Days: Reading scale from study 4. They then answered “How much did you enjoy reading as a child?” “How much did your childhood friends enjoy reading when they were children?” “Now as an adult, how much do you enjoy reading?”

Supplementary Material

http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/10/eaav5916/DC1

Download PDF

Kids these days: Why the youth of today seem lacking

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank D. Gilbert, T. Gilovich, and T. Wilson for their comments on this project; two anonymous reviewers for their help and clarifications; and C. Zedelius for her help with the manuscript. We would also like to thank Dr. Hallgeir Sjåstad for sharing the materials used in Study 5. Funding: We acknowledge the support of grant no. 44069-59380 from the Fetzer Franklin Fund to J.W.S. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Author contributions: Both authors contributed to the manuscript and studies. Data and materials availability: Data and preregistration and supplementary materials for study 1 is at https://osf.io/akeqc/; for study 2 at https://osf.io/a7e5n/; for study 3 at https://osf.io/kx35p/; for study 4 at https://osf.io/5escq/; and for study 5 at https://osf.io/yznwr/.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/10/eaav5916/DC1

Study 1

Study 2

Study 3

Study 4

Study 5

Fig. S1. Preregistered mechanism model of the kids these days effect.

Fig. S2. False feedback figures presented in study 5.

Fig. S3. Causal mediation model tested in study 5.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.H. J. Rose, A New General Biographical Dictionary Projected and Partly Arranged by the Late Rev. Hugh James Rose (B. Fellowes, 1848), vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.K. J. Freeman, Schools of Hellas: An Essay on the Practice and Theory of Ancient Greek Education from 600 to 300 B.C. (Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1907). [Google Scholar]

- 3.C. Smart, The Works of Horace, Translated Literally into English Prose; For the Use of Those who are Desirous of Acquiring or Recovering a Competent Knowledge of the Latin Language (Joseph Whetham, 1836).

- 4.J. Kitt, Kids These Days: An Analysis of the Rhetoric Against Youth Across Five Generations (2013); http://writingandrhetoric.cah.ucf.edu/stylus/files/kws2/KWS2_Kitt.pdf.

- 5.A. Ruggeri, People have always whinged about young adults. Here’s proof (2017); http://www.bbc.com/capital/story/20171003-proof-that-people-have-always-complained-about-young-adults.

- 6.Kanten A. B., Teigen K. H., Better than average and better with time: Relative evaluations of self and others in the past, present, and future. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 38, 343–353 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 7.J. J. Cameron, A. E. Wilson, M. Ross, Autobiographical memory and self-assessment, in Studies in Self and Indenitity. The Self and Memory (Psychology Press, 2004), pp. 207–226. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruger J., Dunning D., Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77, 1121–1134 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross M., Relation of implicit theories to the construction of personal histories. Psychol. Rev. 96, 341–357 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eibach R. P., Libby L. K., Gilovich T. D., When change in the self is mistaken for change in the world. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 917–931 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin C. L., Kornienko O., Schaefer D. R., Hanish L. D., Fabes R. A., Goble P., The role of sex of peers and gender-typed activities in young children’s peer affiliative networks: A longitudinal analysis of selection and influence. Child Dev. 84, 921–937 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zakrisson I., Construction of a short version of the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 39, 863–872 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flynn J. R., The mean IQ of Americans: Massive gains 1932 to 1978. Psychol. Bull. 95, 29–51 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pietschnig J., Voracek M., One century of global IQ gains: A formal meta-analysis of the Flynn effect (1909–2013). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 282–306 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutton E., van der Linden D., Lynn R., The negative Flynn effect: A systematic literature review. Dermatol. Int. 59, 163–169 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 16.E. L. Thorndike, E. O. Bregman, M. V. Cobb, E. Woodyard, Inst of Educational Research Div of Psychology, Teachers Coll, Columbia U, The measurement of intelligence (Teachers College Bureau of Publications, 1926).

- 17.Thorndike R. L., Gallup G. H., Verbal intelligence of the American adult. J. Gen. Psychol. 30, 75–85 (1944). [Google Scholar]

- 18.R. P. Eibach, L. K. Libby, Ideology of the good old days: Exaggerated perceptions of moral decline and conservative politics, in Series in Political Psychology. Social and Psychological Bases of Ideology and System Justification, J. T. Jost, A. C. Kay, H. Thorisdottir, Eds. (Oxford Univ. Press, 2009), pp. 402–423. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sticht T. G., Hofstetter C. R., Hofstetter C. H., Assessing adult literacy by telephone. J. Literacy Res. 28, 525–559 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 20.West R. F., Stanovich K. E., The incidental acquisition of information from reading. Psychol. Sci. 2, 325–330 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 21.H. Sjåstad, R. F. Baumeister, M. Ent, Greener grass or sour grapes? How people value future goals after initial failure (2018); https://osf.io/ak2xy/?action=download.

- 22.Klar Y., Way beyond compare: Nonselective superiority and inferiority biases in judging randomly assigned group members relative to their peers. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 331–351 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giladi E. E., Klar Y., When standards are wide of the mark: Nonselective superiority and inferiority biases in comparative judgments of objects and concepts. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 131, 538–551 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chambers J. R., Why the parts are better (or worse) than the whole: The unique-attributes hypothesis. Psychol. Sci. 21, 268–275 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/10/eaav5916/DC1

Download PDF

Kids these days: Why the youth of today seem lacking

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/10/eaav5916/DC1

Study 1

Study 2

Study 3

Study 4

Study 5

Fig. S1. Preregistered mechanism model of the kids these days effect.

Fig. S2. False feedback figures presented in study 5.

Fig. S3. Causal mediation model tested in study 5.