A prospective cohort study of self-reported computerised medical history taking for acute chest pain: protocol of the CLEOS-Chest Pain Danderyd Study (CLEOS-CPDS) (original) (raw)

Abstract

Introduction

Management of acute chest pain focuses on diagnosis or safe rule-out of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). We aim to determine the additional value of self-reported computerised history taking (CHT).

Methods and analysis

Prospective cohort study design with self-reported, medical histories collected by a CHT programme (Clinical Expert Operating System, CLEOS) using a tablet. Women and men presenting with acute chest pain to the emergency department at Danderyd University Hospital (Stockholm, Sweden) are eligible. CHT will be compared with standard history taking for completeness of data required to calculate ACS risk scores such as History, ECG, Age, Risk factors and Troponin (HEART), Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE), and Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI). Clinical outcomes will be extracted from hospital electronic health records and national registries. The CLEOS-Chest Pain Danderyd Study project includes (1) a feasibility study of CHT, (2) a validation study of CHT as compared with standard history taking, (3) a paired diagnostic accuracy study using data from CHT and established risk scores, (4) a clinical utility study to evaluate the impact of CHT on the management of chest pain and the use of resources, and (5) data mining, aiming to generate an improved risk score for ACS. Primary outcomes will be analysed after 1000 patients, but to allow for subgroup analysis, the study intends to recruit 2000 or more patients. This ongoing project may lead to new and more effective ways for collecting thorough, accurate medical histories with important implications for clinical practice.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been reviewed and approved by the Stockholm Regional Ethical Committee (now Swedish Ethical Review Authority). Results will be published, regardless of the outcome, in peer-reviewed international scientific journals.

Trial registration number

This study is registered at https://www.clinicaltrials.gov (unique identifier: NCT03439449).

Keywords: coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, medical history, health informatics, information management, risk management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

- One strength of this study is the focus on accurate risk prediction for a life-threatening condition among the large group of patients presenting to the emergency department with a common problem.

- Another strength is the prospective, cohort study design, and a large study population with reliable outcomes, for which there are well-established, strict criteria.

- The academic, investigator-initiated and investigator-driven study without any commercial interests adds further strength.

- Potential limitations include selection bias, as some patients may not be able to carry through a computerised interview; there may also be a risk of recall bias caused by giving a medical history twice.

- Furthermore, the generalisability of the study results may be limited with different structure and organisation of emergency departments.

Introduction

Chest pain is one of the most frequent presenting problems in emergency departments (EDs), accounting for as many as 30% of all visits.1 Causes of chest pain range from benign conditions to life-threatening emergencies such as an acute coronary syndrome (ACS; ie, unstable angina pectoris and acute myocardial infarction), which is the acute presentation of ischaemic heart disease, the most common cause of death worldwide.2 A major challenge for physicians is to rule in or rule out ACS accurately because objective evidence for ACS, for example, ECG and circulating biomarkers indicating acute myocardial injury such as troponin usually are imponderable in the early course of evaluation. According to an overview based on both European and US data, disease prevalence in unselected patients presenting to the ED with acute chest pain may be as high as 5%–10% for ST-elevation myocardial infarction, 15%–20% for non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction and 10% for unstable angina pectoris,3 which is consistent with Swedish data.4

Current guidelines emphasise the importance of medical history taking for evaluating chest pain.3 5 However, it has been argued that signs and symptoms of ACS are so variable that careful history taking by a physician is an imperfect tool and sometimes of little help for safely excluding ACS.6 It is argued too that history taking is time consuming and can delay what are regarded as more precise examination methods such as coronary CT angiography.6 7 However, the majority of patients with chest pain in the ED do not have ACS or another emergent issue, so aggressive use of objective methods for finding lesions of the coronary arteries puts many patients at risk for undergoing unnecessary, potentially harmful and costly examinations. Therefore, contemporary guidelines indicate that risk scores should be used to stratify risk for ACS on a patient-by-patient basis. Recommended scoring systems include the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) score and Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score.3 5 More recently, utilisation of the History, ECG, Age, Risk factors and Troponin (HEART) score has been recommended as an effective tool for risk stratification in the ED setting.8 Typically, these scores include information on age, risk factors for coronary artery disease (family history, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes, current smoker), heart failure, renal function, history suspicious for angina, current use of aspirin or diuretics, ST segment deviation on the ECG and elevated serum cardiac biomarkers.9 10

In a hectic ED setting, important information may be missed by medical history taking obtained by the physician (standard history taking). Other approaches have been suggested to ensure collection of more complete and accurate information.11 One way to address this issue is to collect self-reported medical histories via computerised history taking (CHT) programme. Herrick et al conducted a cross-sectional study in an ED setting; 841 patients independently and easily engaged with CHT programme to input data with high accuracy.12 Other studies have shown that CHT performed well in evaluating risk for post-traumatic stress,13 stratifying cardiovascular risk in patients with hypercholesterolaemia14 and for generating a present illness in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms to improve clinic visit efficiency.15 However, in a recent review of the literature for CHT versus oral-and-written history taking for prevention and management of cardiovascular disease, only one other study16 was identified. The authors concluded that there is a need to develop an evidence base to support the use of CHT programme for cardiovascular disease.

Data from CHT together with computer-based decision support systems have demonstrated improved physician performance and better patient outcomes in some cases.17–20 An important prerequisite for useful computer-based decision support, however, is complete, accurate and standardised medical history data.11 21 To date, the data in electronic health records (EHR) in Swedish EDs do not meet the standards required as a basis for computer-based decision support.22 Accordingly, this study aims to determine the additional value of CHT for the management of patients presenting at the ED with chest pain. More specifically, we aim to determine whether self-reported CHT as compared with standard history taking1 improves data quality,2 adds to the accuracy of risk stratification to exclude ACS in patients with chest pain, and3 saves time and resources.

Methods and analysis

Study design

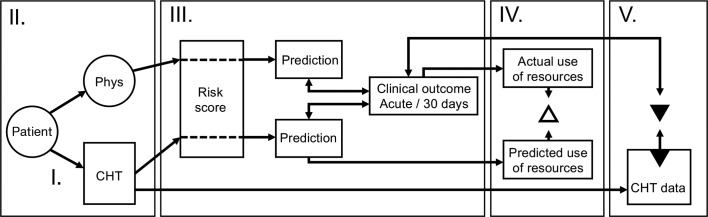

The Clinical Expert Operating System-Chest Pain Danderyd Study (CLEOS-CPDS) is a prospective cohort study designed to determine the value of CHT in the management of acute chest pain (Study protocol version 1.7, dated 16 May 2019). This study follows the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials reporting guidelines.23 The project includes a feasibility study for CHT in the acute setting (study I); a validation study of CHT as compared with standard history taking (study II); a paired diagnostic accuracy study using data from CHT and established risk scores (study III); a clinical utility study to evaluate the impact of CHT on chest pain management and use of resources (study IV); and use of data mining to generate an improved risk score for ACS (study V). A summary of the planned studies is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of planned studies. CHT, computerised history taking; Phys, history taking by physicians.

Study population

Women and men, presenting consecutively at the ED at Danderyd University Hospital (Stockholm, Sweden) from 1 October 2017 until 31 December 2023 (preliminary date), with a chief problem of chest pain are eligible if they meet the criteria in box 1.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

- Women and men, aged 18 years and above

- Chest pain recorded by a triage nurse or registrar

- Fluency in Swedish

- Non-diagnostic first ECG and non-diagnostic serum markers of an acute disease requiring immediate care

- Clinically stable patients (Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System (RETTS) level orange, yellow, green and blue indicating clinical stability)

- Informed consent

Exclusion criteria

- Inability to carry out computerised history taking on the dedicated device (eg, confusion, agitation or inadequate eyesight)

Standard blood biomarkers for an acute disease are haemoglobin, leucocytes, thrombocytes, high-sensitive C reactive protein, sodium, potassium, creatinine, glucose, high-sensitive troponin T and d-dimer.

Danderyd University Hospital, one of four major hospitals in the greater Stockholm region, serves a population of approximately 550 000. The ED has 90 000 annual visits and dedicated units for internal medicine, cardiology, general surgery, orthopaedics and obstetrics/gynaecology. The cardiology unit manages about 20% of acute visits. It is staffed by two (nights) to five (afternoons) junior doctors, who are supervised by a more senior physician, for example, a cardiology consultant or senior resident in cardiology, day and night. As in most Swedish EDs, the triage protocol Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System (RETTS) is used to assess the urgency of each patient's condition, to decide what workup is needed and how the patient should be monitored. Based on vital signs and symptoms collected by a nurse and an assistant nurse, patients are divided into five priority levels depending on their need of urgent medical attention: red (immediate), orange (within 20 min), yellow (within 120 min), green (not in need of immediate care) and blue (not in need of emergency care or hospital facilities).24

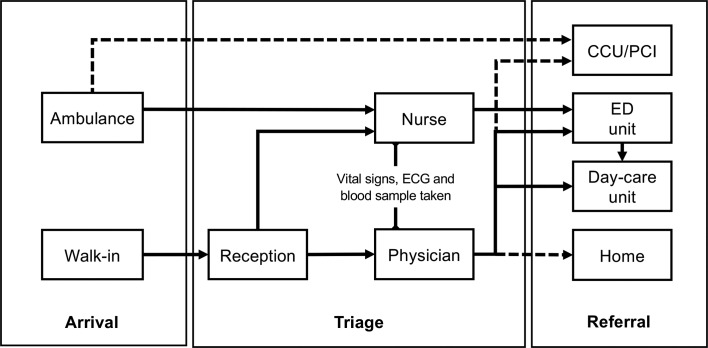

Data collection

When presenting to the ED with chest pain, walk-in patients first report their problem to the reception nurse, who will direct them to the cardiology ED. During weekdays, 10:00–16:00, these patients are triaged promptly by a physician, who is either a cardiology consultant or senior resident in cardiology. The triage includes a decision on the indicated workup, which is based on a targeted medical history, a brief examination, vital signs and ECG. These data are used to determine whether a patient should be admitted to the cardiology ED, the day-care unit or sent home. During out-of-office hours, all patients are triaged by a nurse. According to the RETTS protocol, ECG and biomarkers are acquired before the patient is transported to the cardiology ED. All patients then undergo a more thorough examination and standard history taking by a physician, who also decide whether further investigations are needed. Regional guidelines recommend risk stratification according to HEART score including high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays and the validated 0 h/1 hour rule-in and rule-out algorithm.3 Patients with signs of ST-elevation myocardial infarction on ECG or clinically unstable patients (RETTS level red) are evaluated immediately and admitted to the coronary care unit or brought to the coronary intervention laboratory for acute intervention, when indicated. Thus, critically ill patients are excluded in the present study. See figure 2 for an overview of the ED flow from arrival to referral.

Figure 2.

Overview of the emergency department (ED) flow from arrival to referral. Broken lines indicate patients who will not be eligible. CCU, cardiac care unit; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Patients are asked by a member of the research staff to participate in the current study at the cardiology ED or day-care unit (figure 2). After informed consent has been obtained, histories are collected with a CHT programme during waiting times. CHT histories may occur before or after a patient is seen by a physician. Routine care takes precedence over CHT so that patients interact with the CHT programme only during waiting times. CHT thus will not interfere with workflow or patient care in the ED. During the study period, CHT data will not be available to the care providers.

All answers to CHT-posed questions are time stamped. The time at which the physician first meets the patient also is recorded. This will enable control for possible second-history effects. Patients are asked about technical, semantic and other problems they might have encountered after completing a CHT interview. This will be done as a basis for future corrections and improvements to the CHT programme.

Self-reported medical history data, demographics and other baseline characteristics will be collected from CHT data.

Data from standard history, demographic and baseline characteristics, vital signs and lab data will be extracted from the EHR. To generate the cost associated with routine care, patient-by-patient data on use of resources will be extracted from the hospital EHR. Cost will be correlated with different clinical outcomes by linking the diagnosis at the ED visit or when discharged with their diagnosis-related group (DRG) code, which is an estimate of costs associated with a specific diagnosis provided by the National Board of Health and Welfare and Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions.

The use of unique personal identity doument (ID) number to all Swedish citizens allows linkage to national and regional registries for research purposes. Thus, clinical outcomes in the acute setting (ie, within 7 days) will be extracted from the EHR of the hospital. Discharge diagnoses, at 30 days, and at 1 year, will be collected from the National Patient Register, which includes information on all hospital discharges in Sweden since 1964.25 Mortality status and causes of death will be extracted from the Cause of Death Register which provides official statistics, according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, in Sweden since 1961.26

For the validation and future development of CHT, a questionnaire to assess overall patient experience in a larger sample of patients (n=500) will be developed through interviews with a subset of patients. Approximately, 30 patients will be asked to participate in three to four focus group interviews for the evaluation of ease of use and usefulness of the CHT programme. These interviews will take place 1 to 3 months after the ED visit.

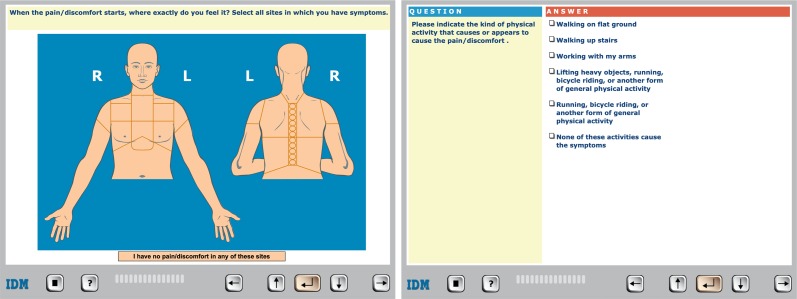

Interventions

Computerised, self-reported medical histories will be collected with the software programme CLEOS running on tablets (iPad, Apple, Cupertino, California, USA). CLEOS is developed by Zakim and colleagues and is owned by Karolinska Institutet, a public university. Details and validation of the CLEOS programme have been described previously.14 27 In brief, the participant answers questions by clicking on a variety of question types, for example, yes/no answers, multiple-choice answers with one allowed answer and multiple-choice answers with more than one allowed answer. Most questions are in a text format but many are images as presented in figure 3. The programme determines dynamically the next most appropriate question. This is done on the basis of the answer to a single prior question and rules that interpret the clinical significance of all prior answers. Each patient is guided through an individually tailored, comprehensive medical interview that includes demographics, present illness, organ systems review, medical history, prescription and over the counter medications, socioeconomic issues, life-style risks and family history. The programme also searches for previous adverse drug reactions. Questions concerning established markers for cardiovascular risk are asked early in the interview for patients with a chief problem of chest pain. Box 2 shows the consecutive order of the major medical blocks of the interview. The occurrence of any block or subsection within a block in the pathway for a specific interview is determined, however, by a patient’s chief problem and answers to questions within specific blocks.

Figure 3.

Example of the presentations of questions in Clinical Expert Operating System on the tablet.

Box 2. Consecutive order of medical blocks in the interview.

- Chief complaint

- Cardiovascular

- Respiratory

- Immunology/rheumatology

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology/gastrointestinal surgery

- Hepatology

- Nephrology and urology

- Obstetrics and gynaecology

- Neurology

- Haematology/oncology

- Mental health

- History medical/surgical events

- Family history

The CLEOS interview is directed by >17 000 decision nodes and can collect >40 000 clinical data elements. The interview can be paused at any question as many times as necessary and resumed automatically at the last unanswered question. The duration of interviews depends on the individual’s pathway, but is approximately 45 min when pauses >2 min are excluded, with the assumption that this indicated the patient being interrupted by other activities such as blood testing, radiology, interview by physician or other staff. Previous studies concerning CHT programme have shown that self-reported, CHT with CLEOS is superior to standard history taking in terms of completeness of data collected.14 27

In previous studies with CLEOS, the interviews were conducted in English or German.14 27 We have adapted the programme to Swedish conditions. A professional translation agency with medical qualifications (Verbal i Nacka AB, Östersund, Sweden) processed all ~35 000 questions and answer sets in the programme. This translation was tested for comprehensibility and cultural adaption in a random sample of 18 persons living in the Stockholm region including both women and men aged between 18 and 80 years. Age, gender, level of education, previous tablet use, issues during the interview and overall comments were tabulated for all these patients. All phrases were re-examined by a trained medical student and also, to get a non-medical perspective, an economics student. The language of all questions and answers was edited to account for country-specific differences (eg, drug use, tobacco use and abuse) among Sweden, Germany and the USA. The penultimate version was verified by a competent physician and then tested by 12 hospitalised patients before a pilot study was started in 400 patients. Additional errors in translation and poor use of language in the original English were resolved continuously in this phase of the work. No additional changes to language were made after the start of the present study.

Sample size calculations

This is an exploratory study. The calculation of the sample size of the study population is based on the targeted precision of sensitivity and specificity. As the prevalence of ACS in the study population is unknown, we have based the calculation of the number of subjects based on the assumption that the prevalence is 0.5 (50 %) which maximises the estimated sample size. To obtain a precision of sensitivity and specificity of ±0.03 (3 %) (nQuery V.7.0, Statistical Solutions, Boston, Massachusetts, USA), 1000 patients are required. The more the extreme the result, that is, sensitivity or specificity approaching 0 or 1 (100 %), the higher the precision and subsequently lower number of subjects needed for this study. The models will be developed in the first 50% of the data acquired (training data set) and validated in the last 50% of the data acquired (validation data set). The primary outcome will be analysed after 1000 patients (with no planned interim analyses), which is expected to be reached by 31 December 2020. We also intend to make estimates in subgroups. To allow these analyses, the study programme intends to ultimately recruit data from at least 2000 patients in total.

Outcomes

The primary objective is to determine whether the use of CHT (index test 1) is better than standard history taking obtained by the physician (index test 2) in attendance (generally a specialist or resident in cardiology) for the prediction and safe exclusion of an ACS in the acute setting in patients with non-diagnostic ECG or serum markers. Thus, the primary outcome (reference test) is the comparison of the accuracy between the two methods for the safe exclusion of ACS or a diagnosis of ACS in the acute setting, that is, within 7 days from the ED visit. The diagnosis of ACS will be based on current European guidelines.3 28 The diagnosis will be validated by an experienced cardiologist. A cross tabulation of the index test results against the reference test will allow estimations for sensitivity, specificity and predictive values. CIs will be calculated. The results will be presented graphically with a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for each index test. Also, likelihood ratios will be calculated.

Secondary outcomes include (1) the ability of CHT, as compared with standard history taking obtained by the cardiologist in attendance to provide information required to calculate recommended risk scores for ACS; (2) a correct exclusion of an ACS up to 30 days and up to 1 year by use of CHT or standard history taking obtained by the cardiologist in attendance; (3) direct costs and resource utilisation for a patient with a diagnosis of an ACS when patient selection is based on CHT, as compared with standard history taking obtained by the cardiologist in attendance; and (4) patient experience with CHT regarding feasibility, acceptance, comprehensible and technical aspects. Finally, we aim to use the collected data to explore the possibility to generate an improved risk score for ACS.

Data management and data analysis plan

The CLEOS interview programme runs from a central server located at Karolinska Institutet, Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, Stockholm, Sweden. Data collected will be stored on this server in the form of codes (not text) representing answers to questions posed. Data transmission and storage fulfil the high standards of security of Karolinska Institutet.

Other data stored are time stamps for completion of each question in an interview, and the pathway by which each interview proceeded. Data collected during routine care, which may be used for algorithm development, for example, signs like heart rate, rhythm, body temperature, blood pressure, biochemistry and findings from ECG recordings will be extracted from the EHRs and added manually to coded data fields in the CLEOS programme.

Descriptive statistics will be used to describe demography and background characteristics (eg, mean values and SD or confidence values, median values and IQRs, or proportions, as appropriate). We will evaluate established risk scores, as populated with CLEOS data, and compare these results with data obtained during the concurrent ED visit and made available in the standard hospital EHR. Regression-based statistical analyses will be used, and appropriate tests for significant difference of completeness of the risk scores (eg, the χ2 test, Student’s t-test and McNemar’s test).

Second, to assess how data collected with CLEOS in combination with established risk scores can rule in and rule out a diagnosis of an ACS, we will calculate sensitivity, specificity and negative and positive predictive values. The results will be presented with ROC curves for each risk score and the Hanley and McNeil method to test for difference. Logistic regression will be used to describe the relationship with the predictions and actual outcomes (ie, ACS or not ACS).

The potential impact on costs by use of information achieved from CHT in managing patients with acute chest pain, compared with standard history taking, will be calculated. Standard health economic principles and methods based on DRG codes and current Swedish tariffs for outpatient care and investigations will be used.

Patient and public involvement

Patients participate at several stages of the study. The patient perspective has been incorporated into this study through interviews during the adaption of the CLEOS programme to Swedish conditions, by providing feedback during the pilot study phase and also during the ongoing study after completion of the interview. Furthermore, interviews with a subset of patients for the evaluation of patient experience regarding feasibility, acceptance, comprehensiveness and technical aspects of answering the CLEOS interview will take place as part to the study protocol (see above). All participating patients are informed about how they can access the registered protocol.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been reviewed and approved by the Stockholm Regional Ethical Committee (now Swedish Ethical Review Authority) (No 2015/1955-1). All participants will give their informed consent before taking part of the study. Results will be published, regardless of the results obtained, in peer-reviewed international scientific journals.

Discussion

Chest pain is a common chief problem in the ED and there are several health and resource benefits if ACS could be ruled in or ruled out more effectively. CHT may be a useful method, but has not been studied previously in an acute cardiology setting. The Swedish healthcare system offers a good opportunity to study this. There are high-quality, comprehensive national healthcare registries and consistent use of EHRs. This ongoing study aims to determine the additional value of CHT for the management of patients with acute chest pain. The pilot phase of the CLEOS-CPDS study was performed 1 May to 30 September 2017 and the recruitment in the main study started on 1 October 2017.

The main strengths of this study include the focus on accurate prediction of risk for a life-threatening condition among the large group of patients presenting to EDs with a common problem.1 Second, we use a prospective, cohort study design; include a large study population; and use reliable outcome measures for which there are well-established, strict criteria.29 Third, the implications of the results on resource utilisation could have a significant impact for healthcare providers. Fourth, the use of CHT does not require a specific EHR system, and CLEOS has a generic layout not specific for cardiology or the ED setting. Thus, the results could be potentially generalised to several other clinical issues and care settings. Finally, our research is academically initiated and driven. The artificial intelligence software in this study is owned by a public university. There are no commercial interests within this research project.

However, a number of possible limitations of this study should be considered. First, patients not able to accomplish CHT are excluded. This may limit the generalisability of the results to all people with chest pain. To address these issues, we will conduct a feasibility analysis on the first 500 patients to compare patient characteristics, their performance with the CHT and demographics and background characteristics with the entire ED population for the same time period. Why patients decline to participate in the study will be reported specifically. Second, given the large number of possible questions during the interview, we cannot dismiss the risk of vague or misleading questions, as they are not all validated. Also, the time for CHT is longer than for a traditional history taken by a physician, which may be a concern with time constraints in an ED setting. However, the results of the current study may help developing future CHT modules which are briefer but with equal or better performance. A risk of recall bias caused by giving a medical history twice (CHT and standard history taking) cannot be excluded. To allow for a sensitivity analysis for this possible bias, we will track the order of interview by physician and CLEOS. Third, there might be a difference in patients reading questions as opposed to answering them verbally. Also, CHT will capture every question asked, whereby the data for standard history taking will be collected from the EHR. Therefore, information captured during standard history taking might not be documented and more complete data from CHT will be expected. These two issues will be addressed when analysing the congruency between CHT and EHR data. Fourth, the effect of patient data collected prior to the history taking, for example, ECG or blood samples collected in the triage is another potential confounding factor as the physician will have access to these data before obtaining history, whereas the CHT will not. This potential confounding may warrant further study. Fifth, as we compare data from CHT with data acquired by the attending physician, the performance of the physician can affect our results. Furthermore, the ED in this study has a specific cardiology unit where the attending physician is a cardiologist. This may limit the application of the results to other settings with an ED with unsorted flow, and/or where ED physicians evaluate all patients.

Supplementary Material

Reviewer comments

Author's manuscript

Footnotes

Twitter: @Helge0

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study and to creating the study protocol. HB, TK and DZ drafted the manuscript. DZ is the designer of the CLEOS program’s method for making medical knowledge actionable and the developer of the program’s medical knowledge base. All authors revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final text. TK (chair), HB, JS, SK, CJS and DZ form the steering group of the CLEOS-CPDS study. CJS acts as the contact person for the trial sponsor (Karolinska Institutet). All steering group members will have full access to the final trial data set. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This work was funded by the Robert Bosch Stiftung (Stuttgart, Germany), grant number 11.5.1000.0258.0, Region Stockholm (ALF project; Stockholm, Sweden), grant number 20190593, Karolinska Institutet Research Foundation (Stockholm, Sweden) and Stiftelsen Hjärtat (Stockholm, Sweden).

Competing interests: DZ is the inventor on US patents for technology related to the CLEOS program. All patent rights and copyrights to technology, language, images and knowledge content are assigned without royalty rights by DZ to Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, which is a public university. Apart from Karolinska Institutet and its subsidiaries, no individuals or companies may be owners or receive royalties or other revenue from use of CLEOS technology, language, images, knowledge content or from clinical insights and/or computer algorithms generated from analysis of data acquired by the program. All CLEOS-CPDS steering group members (see above) will have full access to the final trial data set.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, et al. National Hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2006 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report 2008:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Global health Observatory (GHO) data. World Health Organization, 2019. http://origin.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/causes_death/top_10/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J-P, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2016;37:267–315. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekelund U, Nilsson H-J, Frigyesi A, et al. Patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome in a university hospital emergency department: an observational study. BMC Emerg Med 2002;2:1 10.1186/1471-227X-2-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: Executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American heart association Task force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2014;130:2354–94. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swap CJ, Nagurney JT. Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2005;294:2623–9. 10.1001/jama.294.20.2623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieman K, Hoffmann U. Cardiac computed tomography in patients with acute chest pain. Eur Heart J 2015;36:906–14. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Six AJ, Cullen L, Backus BE, et al. The heart score for the assessment of patients with chest pain in the emergency department: a multinational validation study. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2013;12:121–6. 10.1097/HPC.0b013e31828b327e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox KA, Dabbous OH, Goldberg RJ, et al. Prediction of risk of death and myocardial infarction in the six months after presentation with acute coronary syndrome: prospective multinational observational study (GRACE). BMJ 2006;333:1091 10.1136/bmj.38985.646481.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: a method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA 2000;284:835–42. 10.1001/jama.284.7.835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox JL, Zitner D, Courtney KD, et al. Undocumented patient information: an impediment to quality of care. Am J Med 2003;114:211–6. 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01481-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrick DB, Nakhasi A, Nelson B, et al. Usability characteristics of self-administered computer-assisted interviewing in the emergency department. Appl Clin Inform 2013;4:276–92. 10.4338/ACI-2012-09-RA-0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corrigan M, McWilliams R, Kelly KJ, et al. A computerized, self-administered questionnaire to evaluate posttraumatic stress among firefighters after the world Trade center collapse. Am J Public Health 2009;99(Suppl 3):S702–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zakim D, Fritz C, Braun N, et al. Computerized history-taking as a tool to manage dyslipidemia. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2010;6:1039–46. 10.2147/VHRM.S14302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almario CV, Chey W, Kaung A, et al. Computer-Generated vs. physician-documented history of present illness (HPI): results of a blinded comparison. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:170–9. 10.1038/ajg.2014.356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pappas Y, Všetečková J, Poduval S, et al. Computer-Assisted versus Oral-and-Written history taking for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of the literature. Acta Med 2017;60:97–107. 10.14712/18059694.2018.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunt DL, Haynes RB, Hanna SE, et al. Effects of computer-based clinical decision support systems on physician performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA 1998;280:1339–46. 10.1001/jama.280.15.1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garg AX, Adhikari NKJ, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;293:1223–38. 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raschke RA, Gollihare B, Wunderlich TA, et al. A computer alert system to prevent injury from adverse drug events: development and evaluation in a community teaching hospital. JAMA 1998;280:1317–20. 10.1001/jama.280.15.1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen R, Valladares C, Corbal I, et al. Early experiences from a guideline-based computerized clinical decision support for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Stud Health Technol Inform 2013;192:244–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berner ES, Kasiraman RK, Yu F, et al. Data quality in the outpatient setting: impact on clinical decision support systems. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2005:41–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skyttberg N, Chen R, Blomqvist H, et al. Exploring vital sign data quality in electronic health records with focus on emergency care warning scores. Appl Clin Inform 2017;8:880–92. 10.4338/ACI-2017-05-RA-0075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Widgren BR, Jourak M. Medical emergency triage and treatment system (METTS): a new protocol in primary triage and secondary priority decision in emergency medicine. J Emerg Med 2011;40:623–8. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooke HL, Talbäck M, Hörnblad J, et al. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:765–73. 10.1007/s10654-017-0316-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zakim D, Braun N, Fritz P, et al. Underutilization of information and knowledge in everyday medical practice: evaluation of a computer-based solution. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2008;8:50 10.1186/1472-6947-8-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018;39:119–77. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur Heart J 2019;40:237–69. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Reviewer comments

Author's manuscript