Psychometric Evaluation of the TIC Grade, a Self-Report Measure to Assess Youth Perceptions of the Quality of Trauma-Informed Care They Received (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2023 Jul 1.

Published in final edited form as: J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2020 Sep 10;28(4):319–325. doi: 10.1177/1078390320953896

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Agencies and clinical practices are beginning to provide trauma-informed care (TIC) to their clients. However, there are no measures to assess clients’ perceptions of and satisfaction with the TIC care they have received. A 20-item questionnaire, the TIC Grade, was developed, based on the National Center for Trauma-Informed Care principles of TIC, to assess the patient or client perception of the TIC provided in settings that serve adolescents and emerging adults.

OBJECTIVE:

The goal of this project was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the TIC Grade instrument and to make recommendations for use of the full measure and its short form—an overall letter grade.

STUDY DESIGN:

The TIC Grade questionnaire was administered to youth over the age of 18 years from four community partners providing care to vulnerable young adults. Potential participants were offered questionnaires at the end of their visit. Those interested in participating left their completed anonymous questionnaire in a locked box to maintain confidentiality. Questionnaires were collected from 100 respondents; 95 were complete enough to include in analyses for psychometric evaluation.

RESULTS:

The findings of this project support the reliability and usability of the 20-item TIC Grade measure to assess youth’s perceptions of the quality of TIC they received.

CONCLUSIONS:

This TIC-specific, behaviorally worded client report measure can assist service delivery organizations to assess their success at implementing TIC and to identify areas where further staff training and support are needed.

Keywords: abuse, partner, child

Background

The association between Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) or toxic stress during childhood and poor physical and emotional health outcomes later in life is well documented (Anda et al., 2008; Felitti et al., 1998; Kalmakis & Chandler, 2015). Research has shown that life expectancies have been cut short by up to 20 years due to childhood toxic stress (Brown et al., 2009). In addition to poor physical health outcomes, trauma often leads to mental health issues (Afifi et al., 2008). It is estimated that between 25% and 61% of people have experienced at least one adverse childhood experience (Gerson & Rappaport, 2013). Because of all this, ACEs are now considered a major public health concern (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019; Hughes et al., 2017).

While social agencies and health care practices are encouraged to start to implementing trauma-informed care (TIC; American Academy of Pediatrics, 2020; Harris & Fallot, 2001; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014), research supporting this approach is still evolving, and evaluation of these practices are limited. For example, the primary focus of research has been on evaluating staff awareness of the impact of trauma and staff’s response to training about TIC (Green et al., 2016; Purtle, 2018). Instruments like the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care tool have been developed and validated to measure staff attitudes related to TIC (Baker et al., 2015). Research has also focused on the importance of developing tools such as the Pediatric ACEs and Related Life-event Screener (Koita et al., 2018) to assess and screen for ACEs in their clients and to address the impact of early-life adversity in their practice setting (Burke Harris et al., 2017). While these tools are important, it is also essential to understand how the youth perceive TIC as it is being delivered and if they feel this care is addressing their needs. Recently, an instrument, the TIC Grade questionnaire, was developed (Sinko et al., 2020) to obtain youth perceptions to perceive the TIC they received. This will allow service delivery organizations and providers to assess the degree of their success with implementing TIC with their clients based on their clients’ perceptions.

Objective

The overall objective of this study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the TIC Grade questionnaire as a measure of youth (also known as young adults) satisfaction with the TIC received. The population of focus was youth older than age 18.

Questionnaire Development

Details of the action research project used to engage community youth in questionnaire development is described in a separate companion paper (Sinko et al., 2020). A brief summary is provided here. A 20-item questionnaire was created through the use of the deductive process of substructing the construct of TIC proposed by the National Center for Trauma-Informed Care’s principles and practices (SAMHSA, 2014). Youth were recruited using the principles of community-based participatory research to create a community youth advisory board (CYAB). The youth group met weekly to receive training on cognitive interviewing, trauma, and TIC. The initial draft questionnaire created through substruction (Dulock & Holzemer, 1991) was then modified and edited inductively with input from the CYAB based on mutual goals they created with our study team. Additionally, the CYAB worked to ensure that the questionnaire would be easy for youth to fill out, that it would not trigger a traumatic stress response for the participant, and that it was at an appropriate literacy level. Last, the advisory board youth conducted cognitive interviews with other adolescents to further refine the questionnaire prior to psychometric analysis.

Procedures

Prior to starting data collection, the study was classified as exempt by the university institutional review board. After approval, study coordinators met with the community partner to explain the study and answer all questions. After an orientation to the study, the individual sites determined if they were willing to participate in data collection. Four community partners were asked to participate, and all four community partners agreed to participate in the study. All four community partners are located in Southeastern Michigan and provide a variety of services to homeless youth and their families. These organizations provided a range of health and social care services, from primary care to adolescents and emerging adults, to shelter and transitional housing, to social support and counseling, to sexual and reproductive health services. Lock boxes with a slot to submit the forms and paper questionnaires were delivered to each data collection site to maintain confidentiality. The only identifying data on the questionnaire was a code number identifying the community partner data collection site.

Description of the TIC Grade Questionnaire

The TIC Grade Questionnaire consists of a total of 20 items divided into three sections and is a self-report measure. At the beginning of the survey, there is an introductory paragraph that defines trauma, assures the user of anonymity, and asks the user to rate the staff on “how well they pay attention to trauma.” The first section consists of five items asking about how staff “seem to keep trauma in mind.” Each item reflects the “4 R practices” of a trauma-informed approach (SAMHSA, 2014; _R_ealizes the impact or trauma; _R_ecognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma; _R_esponds by integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and seeks to actively _R_esist retraumatization).

The second section of the measure consists of 11 items, highlighting elements of the six key principles of a trauma-informed approach (SAMHSA, 2014). These include (a) safety; (b) trustworthiness and transparency; (c) peer support; (d) collaboration and mutuality; (e) empowerment, voice, and choice; and (f) cultural, historical, and gender issues. The questionnaire items related to trauma-informed practices (TIPs) and principles were rated as not at all (−2), somewhat (−1), you can’t tell (0), a little bit (+1), and very much so (+2). There is a final item in this section that asks the respondent to assign an overall letter grade (ranging from A = excellent to F = failing, unacceptable) as a global appraisal of how well the agency/provider is providing TIC. Last, there is a space asking the respondents to provide comments to help the organization improve their TIC.

The third section of the measure consists of three items asking about the respondents’ experience of trauma in their life. This provides information about survivor status in relation to the three Es of the trauma definition (SAMHSA, 2014): _E_vent(s), _E_xperience of the events, and _E_ffects, including whether trauma was affecting the visit. These items are not part of the total score. Their purpose in the tool is to allow organizations to obtain a clear picture of whether the respondents have experienced trauma, are experiencing lasting effects, and whether trauma was a factor in the services they sought on that day.

Scoring of the TIC Survey

The first and second sections of the TIC Grade consist of 16 questions graded on a Likert-type scale ranging from not at all to very much so. These responses are scored with not at all (−2), somewhat (−1), you can’t tell (0), a little bit (1), and very much so (2). The 17th question is a global rating. It is scored similarly to an academic letter grade scale: A (4), B (3), C (2), D (1), E (0), and F (0).

Ratings from the third section provide a picture of the respondents’ trauma experience. These items are not part of the total score. Their purpose is to allow the organization to know whether the respondents have experienced trauma, whether they are experiencing lasting effects, and whether trauma was a factor in the services they sought on that day.

Based on our recent psychometric evaluation of the TIC Grade survey, it is recommended that the two subscales be used as separate indicators of important components of TIC. Factor analysis showed that these were two distinct scales reflecting assessment of (a) trauma practices and (b) trauma principles. Both scales demon-strated high reliability scores. The 5-item “4 R practices” subscale had a coefficient alpha of .965, and the 11-item “6 P principles” subscale had a similarly high coefficient alpha of .933.

To best assess TIC services, we recommend using all 16 items to collect evaluation data whenever possible. This will provide a clearer picture of TIC received. Our analyses found that the global TIC showed a reasonable correlation between the “grade given” and the subscales. If time is too short or service users are unwilling to reflect and rate their TIC in detail, obtaining a global TIC Grade may provide valid feedback.

Subscale scores can be obtained by computing a mean score for any subject answering a minimum of four of the five questions on the “4 R practices” scale and 10 of the 11 questions on the “6 P principles” scale. A total score can be obtained by computing the mean of the Likert-type scale of 17 items. An overall average score of a −2 or a −1 reflects that the clients/patients who participated in the survey did not feel that the organization provides care that is trauma informed. An overall average score of 0 reflects that the clients/patients do not agree or disagree that the organization provides TIC. An average score of 1 or 2 indicates that participants feel that the organization provides TIC.

Method

For this research project, the questionnaire packet begins with an introductory letter explaining the study. Participants were told that their name would not be on the questionnaire nor would their providers be identified. The participants were informed that their responses would not affect their provider’s evaluation or job. Participants were informed that filling out the questionnaire was voluntary and their care at the site would not be affected. Last, they were informed that by filling out the questionnaire, the participants were consenting to participate in the study.

Questionnaires were delivered to each of the data collection sites along with a locked box for collecting the completed questionnaires. Data were collected over 4 months at the four community locations. Each of these community partners provides services to homeless youth and their families. Some of the services provided include (a) drop in for a meal or shower, (b) job counseling, (c) health services, (d) counseling services, (e) LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and, queer) support services, (f) alcohol and drug abuse counseling, and (g) working with the community school district to keep homeless youth in school. Staff members of the agency handed a questionnaire to the potential participants at the end of each visit with the community partner. Potential participants were asked to read the cover letter attached to the questionnaire. The cover letter explained the study and the option to participate or not participate. Participants then either left the questionnaire uncompleted or completed the questionnaire and placed it in a locked box. Every 2 weeks during data collection, the research assistant collected the questionnaires, and the responses were entered into REDCap, a secure electronic data capture system and analyzed in SPSS Version 25.

Plan for Psychometric Analysis

To conduct psychometric analysis, questionnaires that had substantial missing data because the client did not finish the form were excluded from the factor analysis. For other statistical tests, missing ratings were imputed by a means that a community organization could easily use—by substituting the respondent’s mean rating. On some items, clients circled two numbers or put a mark between two ratings; these ambiguities were resolved by means a community organization could use—by a coin toss—with heads resulting in the higher number being recorded. Internal consistency/reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. Content validity was assessed using principal axis factoring, applying rotations to optimize the scale. Correlations were also conducted between the single-item appraisal, the letter grade from which this measure gets the “TIC Grade” name, and subscales where all elements of the TIPs and principles are appraised. The purpose of the correlation was to assess how well the “grade” could potentially substitute for a score derived from using the full questionnaire in situations where the full scale is too long or where a verbal option is needed. We also explored correlation of the subscales with the trauma history variables to assess if ratings differed by history.

Results

Description of Sample

Forms were collected from 100 respondents. Eight respondents had missing ratings for one or more questionnaire items. These eight questionnaires were excluded from the factor analysis. The respondent’s scale mean for the missing rating was substituted for the reliability and correlation analyses. Trauma history or TIC Grade responses with missing data were left missing.

The sample was fairly evenly distributed across youth seeking services to meet housing, drop-in support, and sexual health needs. Just over half were trauma survivors; 87% of those reported lasting trauma effects. Of these, 37% stated that trauma-related issues affected their visit.

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptions of participants’ reason for using services, trauma history, and TIC Grade distribution, and distributions of ratings on the subscales and total scale are presented in Table 1. The distribution of the global “TIC Grade” (the letter grade) assigned was skewed toward high marks, with 65% assigning an A grade and only one person assigning an F or failing grade. The full range of negative to positive scores were used on both subscales.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Services used (N = 95) | ||

| Housing-related needs | 31 | 32.6 |

| Drop-in support | 28 | 29.5 |

| Sexual health | 36 | 37.9 |

| Trauma answer positivea (N = 94) | ||

| Did something happen to you that harmed your body or mind or was a threat to your life? (Was it an event, series of events, or a set of circumstances?) = Yes | 52 | 55.3 |

| If so, is it having a lasting effect on you? (Does it get in the way of your school, work, family roles, or lower your mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being now?) = Yes | 45 | 47.9 |

| Did trauma-related issues affect your visit today? = Yes | 19 | 20.2 |

| Trauma-Informed Care Grade (N = 92) | ||

| A (excellent) | 60 | 65.2 |

| B (good) | 21 | 22.8 |

| C (fair) | 10 | 10.9 |

| D (poor) | 0 | 0 |

| F (failing) | 1 | 1.1 |

| Ratings (n = 95) | M | Mdn | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 R practice | 5.9 | 8 | 10.0 |

| 6 Principles | 15.6 | 20 | 10.0 |

| Combined total | 21.4 | 28 | 14.0 |

| Grade | 4.5 | 5 | 0.8 |

Psychometric Analyses

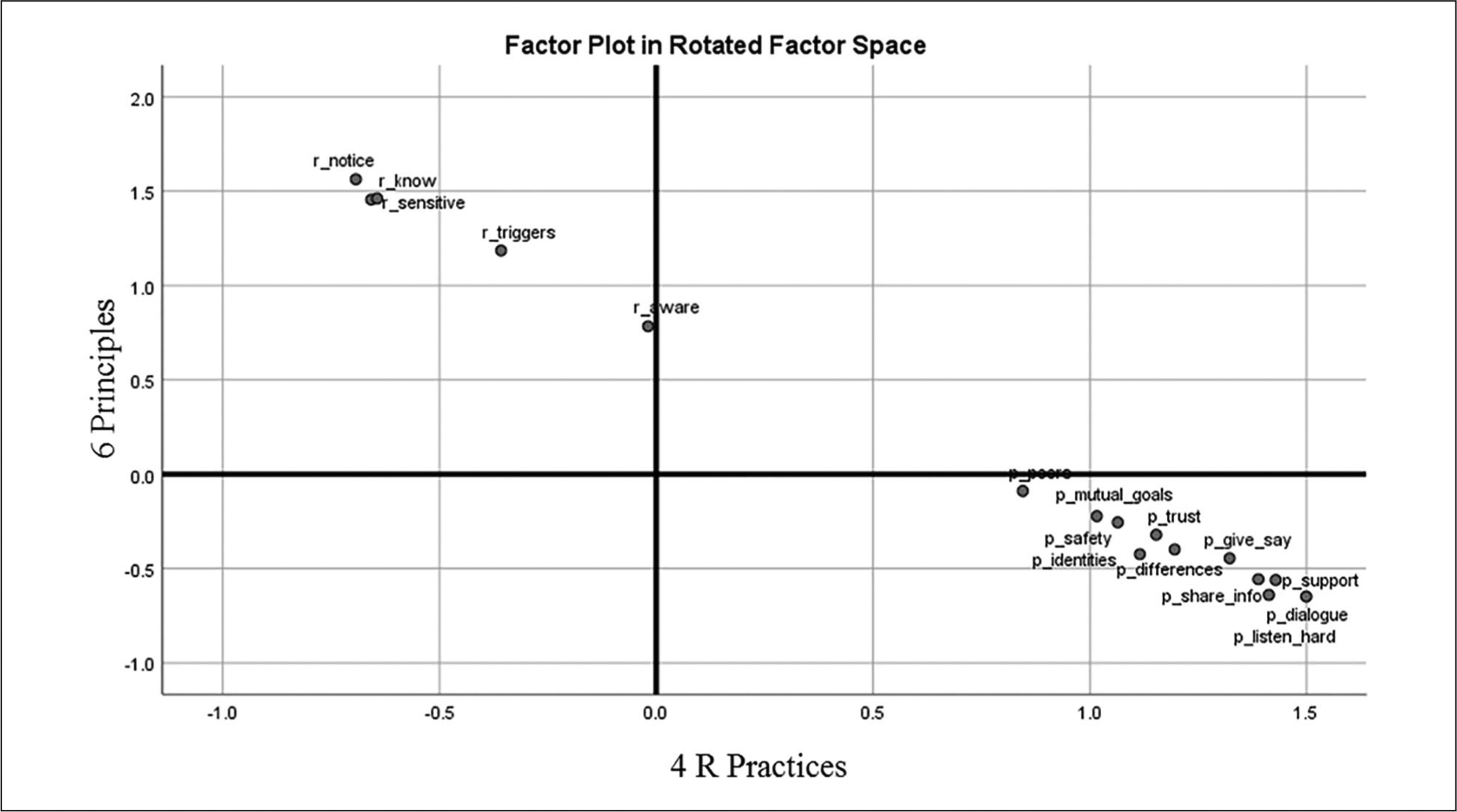

Principal axis factoring resulted in a two-factor solution based on eigenvalue and scree plot. With a one-factor solution, variance explained was 64.87. The second factor added 8.58 additional explained variance for a total of 73.46. Examination of the factor loadings without rotation indicated that the loadings aligned with the 4 R practices and the 6 P principles, reflecting the theory from which the items were substructed. Three rotations—varimax, oblimin, with delta set at .8 were applied. All three placed the same items in the two subscales. The oblimin rotation with delta set at .8 and the plot of the items are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Plot of oblimin rotation with delta set at 0.8.

Interitem correlations were strong but not to the point of redundancy, ranging from .597 to .861. The five-item, 4 R practices subscale mean was 5.9 (SD = 10.0) and α was .933 and would not have been improved by deleting any items. The 11-item, 6 P principles subscale internal consistency analysis was very similar. The mean was 15.6 (SD = 10.0). Interitem correlations ranged from .518 to .881. The 6 P principles subscale α was .965 and would not have been improved by deleting any items. These subscales were correlated with one another at r = .708, p < .05. Although an α > .9 may suggest redundant items that could be deleted for parsimony, this scale was substructed from an established, widely used framework, and thus we opted to retain the items to keep tight congru-ence with the framework.

The single-item global rating framed as the “TIC Grade” was moderately correlated with the 4 R practices subscale (r = .529, p < .05) and the 6 P principles subscale (r = .600, p < .01). There was a weak but statistically significant negative correlation of lasting effect of trauma with the 6 Ps subscale (ρ = −.209, p < .05). This suggests that adolescent clients with lasting effects of trauma may judge organizations more harshly than their peers experiencing fewer lasting effects, but otherwise perceptions did not differ by client history or current effects of trauma on the client.

Discussion

The results of this study support the use of the TIC Grade questionnaire as a simple but effective measure to assess youths’ perspectives on the quality of TIC provided to them. The TIC Grade fills an important need as professionals and organizations seek to implement TIC and need feedback. This can be useful for agencies and providers who are planning to implement TIPs in their organizations to collect baseline data and subsequent assessment after staff trainings and TIC program implementation. This could also be useful as a way for those currently providing TIC to assess how their approach is perceived by the individuals they serve. This instrument also responds to a need for an intervention research measure of the extent to which clients perceive (and thus receive) TIC (Bellg et al., 2004). A review of available measures examining TIC service delivery is presented in a companion paper describing the development of the TIC Grade (Sinko et al., 2020) and are cited here (Baker et al., 2015; Bassuk et al., 2017; Crandal et al., 2019; Goodman et al., 2016; Richardson et al., 2012). Of these, only the TIP scales, a measure created specifically to assess TIC in domestic violence shelters, assess TIC from the client perspective (Goodman et al., 2016). The other measures cited assess from the practitioner or organization perspective.

The paper form deposited in a locked box was a convenient, low-tech process but resulted in some ambiguous markings. Ambiguous marking (e.g., circling two numbers next to each other) introduces a small amount of error that is acceptable in evaluation work. The preference for paper forms may outweigh the problem of a small amount of error in some settings. An electronic form, especially one that could be completed via phone at the client’s convenience, could decrease this rating problem that occurs on paper forms and might decrease the number of incomplete questionnaires. The evaluation form, cover letter template, and scoring instructions are available via our research group website at the University of Michigan School of Nursing website (https://nursing.umich.edu/research/cascaid).

The psychometric analyses support the reliability and validity of the TIC Grade Questionnaire as a measure of the TIPs and principles delineated by the National Center for Trauma-Informed Care (SAMHSA, 2014). Factor analyses were consistent in supporting the two subscales as indictors of separate aspects of TIC. This allows agencies or providers to assess both their TIPs as well as their application of the principles of TIC. Using all 16 items to collect evaluation data is encouraged whenever possible in order to get a more comprehensive view of care provided.

The results also showed a reasonable correlation between the single-item global “TIC Grade” and the two subscales, so if time is an issue or service users are unwilling to reflect and rate their care in detail, obtaining their response to the global TIC Grade question “What overall rating or grade would you give the staff for how well they’re doing Trauma-Informed Care?” may provide valid feedback useful to the agency. It is interesting to note that, in this study, respondents who indicated lasting effects from trauma rated the services received as less trauma informed. That said, the correlation with overall survivor status was weak; this suggests that the providers’ behaviors can be appraised regardless of client trauma history.

Youth in this study availed themselves of the entire range of rating options for each of the practices and principles subscales, suggesting that they are willing to indicate very negative experiences as well as very positive ones. The overall distribution of ratings was skewed to the positive, consistent with most ratings of satisfaction. An implication of this ceiling effect is that agencies may want to query the reasons for low ratings to obtain feedback, and they may want to use reduction in low ratings as an indication of improvement rather than change in the mean alone.

Further research is needed to validate the TIC Grade Questionnaire, in particular with a broader age range of youth and potentially with children or adults. The measure was created for use with adolescents and emerging adults in mind, but it could be useful for any population familiar with the U.S. letter grade system. The letter grade rating approach was selected by the CYAB over the alternative of a 5-star rating concept, which is now broadly used in online ratings and reviews. Grades on the A to E or F scale have been the dominant system in U.S. education for generations, applied in primary, secondary, and postsecondary schooling, making it entirely possible that the TIC Grade could be used with children and adults as reliably and validly as with the youth who co-created and used it in this project. Additional research to conduct confirmatory factor analyses is warranted. Other types of validity testing would strengthen the tool development. This could include evaluation of the extent to which the tool is able to discern improvements in service delivery (i.e., Is it sensitive to the practitioner or agency staff training in TIC?).

Conclusion

The findings of this project support the reliability and usability of the TIC Grade Questionnaire to assess youth’s perceptions of the quality of TIC they received. This information will assist service delivery organizations to assess their success at implementing TIC and to identify areas where further staff training and support are needed. This will further support the partnership between patient or client and provider in promoting and improving the trauma-informed approach in clinical practice so greatly needed by this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank CAsCAid Research Group, University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was partially supported by generous grants from the Janet Gatherer Boyles Fund and the Child Adolescent Research Donations Fund.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Afifi TO, Enns MW, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJ, Stein MB, & Sareen J (2008). Population attributable fractions of psychiatric disorders and suicide ideation and attempts associated with adverse childhood experiences. American Journal of Public Health, 98(5), 946–952. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Becoming a trauma-informed practice. www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/resilience/Pages/Becoming-a-Trauma-Informed-Practice.aspx

- Anda RF, Brown DW, Dube SR, Bremner JD, Felitti VJ, & Giles WH (2008). Adverse childhood experiences and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 34(5), 397–403. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CN, Brown SM, Wilcox PW, Overstreet S, & Arora P (2015). Development and psychometric evaluation of the attitudes related to trauma-informed care (ARTIC) scale. School Mental Health, 8, 61–76. 10.1007/s12310-015-9161-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL, Unick GJ, Paquette K, & Richard MK (2017). Developing an instrument to measure organizational trauma informed care in human services: The TICOMETER. Psychology of Violence, 7(1), 150–157. 10.1037/vio0000030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, Ogedegbe G, Orwig D, Ernst D, & Czajkowski S (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology, 23(5), 443–451. 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DW, Anda RA, Tiemeier H, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB, & Giles WH (2009). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 37(5), 389–396. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke Harris N, Silvério Marques S, Oh D, Bucci M, & Cloutier M (2017). Prevent, screen, heal: Collective action to fight the toxic effects of early life adversity (Open Access). Academic Pediatrics, 17(7), S14–S15. https://doi.org10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Preventing adverse childhood experiences: Leveraging the best available evidence. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Crandal B, Martin J, Hazen A, & Reutz JR (2019). Measuring collaboration across children’s behavioral health and child welfare systems. Psychological Services, 16(1), 111–119. 10.1037/ser0000302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulock HL, & Holzemer WL (1991). Substruction: Improving the linkage from theory to method. Nursing Science Quarterly, 4(2), 83–87. 10.1177/089431849100400209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, & Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and house-hold dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerson R, & Rappaport N (2013). Traumatic stress and posttraumatic stress disorder in youth: Recent research findings on clinical impact, assessment, and treatment. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(2), 137–143. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Sullivan CM, Serrata J, Perilla J, Wilson J, Fauci J, & DiGiovanni CD (2016). Development and validation of the Trauma-Informed Practice Scales. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(6), 747–764. 10.1002/jcop.21799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Saunders PA, Power E, Dass-Brailsford P, Bhat Schelbert K, Giller E, Wissow L, Hurtado de Mendoza A, & Mete M (2016). Trauma-informed medical care: Patient response to a primary care provider communication training. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 21(2), 147–159. 10.1080/15325024.2015.1084854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M, & Fallot RD (Eds.). (2001). New directions for mental health services: Using trauma theory to design service systems. Jossey-Bass. 10.1002/yd.23320018903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, Jones L, & Dunne M (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmakis KA, & Chandler GE (2015). Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: A systematic review. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27(8), 457–465. 10.1002/2327-6924.12215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koita K, Long D, Hessler D, Benson M, Daley K, Bucci M, Thakur N, & Burke Harris N (2018). Development and implementation of a pediatric adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and other determinants of health questionnaire in the pediatric medical home: A pilot study. PLoS One, 13(12), e0208088. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purtle J (2018). Systematic review of evaluations of trauma-informed organizational interventions that include staff trainings. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(4), 725–740. 10.1177/1524838018791304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MM, Coryn LS, Henry J, Black-Pond C, & Unrau C (2012). Development and evaluation of the Trauma-Informed System Change Instrument: Factorial validity and implications for use. Journal of Child and Adolescent Social Work, 29, 167–184. 10.1007/s10560-012-0259-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinko L, Beck D, Seng J (2020) Developing the TIC Grade: A youth self-report of perceptions of trauma informed care. Journal of American Psychiatric Nurses Association. (revise and resubmit) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach (HHS Publication No. 14–4884). https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4884.pdf