Placental cord drainage after vaginal delivery as part of the management of the third stage of labour (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

Cord drainage in the third stage of labour involves unclamping the previously clamped and divided umbilical cord and allowing the blood from the placenta to drain freely into an appropriate receptacle.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the specific effects of placental cord drainage on the third stage of labour following vaginal birth, with or without prophylactic use of uterotonics in the management of the third stage of labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (February 2010).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing placental cord draining with no placental cord drainage as part of the management of the third stage of labour.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the quality of trials and extracted data. This was then verified by the third review author who then entered the agreed outcomes to the review.

Main results

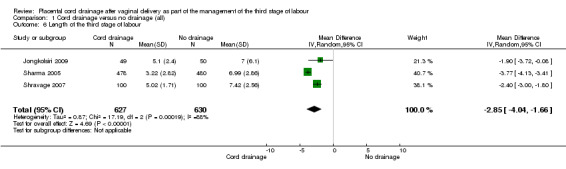

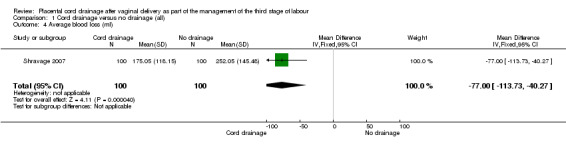

Three studies involving 1257 women met our inclusion criteria. Cord drainage reduced the length of the third stage of labour (mean difference (MD) ‐2.85 minutes, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐4.04 to ‐1.66; three trials, 1257 women (heterogeneity: T² = 0.87; Chi²P=17.19, I² = 88%)) and reduced the average amount of blood loss (MD ‐77.00 ml, 95% CI ‐113.73 to ‐40.27; one trial, 200 women).

No incidence of retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth was observed in the included studies, therefore, it was not possible to compare this outcome. The differences between the cord drainage and the control group were not statistically significant for postpartum haemorrhage or manual removal of the placenta. None of the included studies reported fetomaternal transfusion outcomes and there were no data relating to maternal pain or discomfort during the third stage of labour.

Authors' conclusions

There was a small reduction in the length of the third stage of labour and also in the amount of blood loss when cord drainage was applied compared with no cord drainage. The clinical importance of such observed statistically significant reductions, is open to debate. There is no clear difference in the need for manual removal of placenta, blood transfusion or the risk of postpartum haemorrhage. Due to small trials with medium risk of bias, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Plain language summary

Placental cord drainage after vaginal delivery as part of the management of the third stage of labour

The third stage of labour begins immediately after the birth of the baby and ends with the expulsion of the placenta and fetal membranes. It is preceded by contraction and retraction of the uterus to reduce uterine size and expel the placenta with minimal haemorrhage. The third stage of labour can be managed actively or by expectant management, where the umbilical cord remains attached to the baby until after delivery of the placenta; blood within the placental compartment drains into the baby. Placental cord drainage involves clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord after the birth of a baby and then, immediately unclamping the maternal side of the cord so the blood can drain freely into a container. This may or may not, be used together with other interventions such as routine administration of an oxytocic drug (to contract the womb), controlled cord traction (applying traction to the cord with counter‐pressure on the womb to deliver the placenta) or maternal effort.

This review included three studies involving 1257 birthing women. The findings showed that placental cord drainage in the management of third stage of labour reduced the length of third stage of labour by a mean of about three minutes and reduced blood loss by average of 77 ml. There was no clear difference in the manual removal of placenta or the risk of postpartum haemorrhage or incidence of blood transfusion. The trials did not report on maternal pain or discomfort during the third stage of labour. Some of the outcomes were not reported in the same way in all trials, limiting the amount of information available for analysis. Other desired outcomes were either not reported or were not reported in an appropriate way for statistical analysis (e.g. placenta not delivered within 30 minutes after birth, maternal haemoglobin changes). Further investigation of the effect of placental cord drainage on maternal outcomes would be useful although it is not a priority area for maternity research.

Background

The third stage of labour begins immediately after the birth of the baby and ends with the expulsion of the placenta and fetal membranes. It is preceded by contraction and retraction of the uterus and reduction of uterine size. Reduction of the internal surface of the uterus and limited placental elasticity, leads to separation from the uterus. A study of ultrasonographic imaging on the third stage of labour showed that the thickening and shortening of the placental site of the uterine wall is the major driving force in the process of placental detachment (Herman 1993). These investigators did not notice any haematoma (blood clot) formation between the placenta and the uterine wall as described in the traditional Duncan‐Schultze theory of placental separation. A haematoma is sometimes formed between the separating placenta and the remaining decidua, which is believed to be the result rather than the cause of separation. It may, however, accelerate the process of separation (Cunningham 2010; Fraser 2009). In the absence of a clear understanding of the physiology of placental separation, in order to optimise outcomes, trials tend to focus on different management techniques.

The third stage of labour is generally managed using two different approaches: 'active management' and 'physiological or expectant management'. The former method involves administration of an oxytocic drug, clamping and cutting the cord as well as controlled cord traction. The type and timing of the oxytocic drugs, route of administration, and timing of the cord clamping may vary considerably between practitioners. The latter form of management mainly involves maternal effort assisted by gravity and/or putting the baby to the breast without using artificial oxytocics or early clamping or controlled cord traction (Gyte 1994). In this type of management, if clamping was required due to maternal request or any other reason, it is usually done after cord pulsation is stopped.

In the UK, it is currently common practice to clamp both sides of the cord and cut it immediately after the birth of the baby. However, originally, the two main underpinning reasons for clamping the maternal end of the cord are suggested to be (a) to avoid soiling of the bedclothes with blood, and (b) maternal ligature, as a means of knowing if the cord has been lengthened, signifying placental separation (Botha 1968). Some practitioners may consider applying a clamp on the cord as necessary for effective controlled cord traction.

Placental cord drainage has been suggested as a way of minimising the impact of cord clamping on the third stage of labour for mothers. It involves the clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord after delivery of the baby but, afterwards, immediately unclamping the maternal side of the cord and allowing the blood from the placenta to drain freely into a container. It has been suggested that draining blood from the placenta would reduce its bulkiness, allowing the uterus to contract and retract, thus aiding delivery (Wood 1997). There are anecdotal beliefs among some practitioners that allowing placental cord drainage enhances delivery of the placenta and reduces third stage complications. Fetomaternal haemorrhage (Sharma 1995; Soltani 20005a) and discomfort or pain during the third stage can also be affected by the amount of residual blood in the placenta.

In a normal physiological third stage of labour, the umbilical cord is not clamped until after delivery of the placenta, permitting placental transfusion. The placental transfusion has been shown to be complete by two to five minutes after the birth, in most infants (Farrar 2011). This allows the 'drainage' of blood within the placental compartment into the baby. Clamping the cord at birth followed quickly by unclamping and drainage is close to the physiological process from the mother's viewpoint. Although it can still be considered as an intervention, it is much less so than maintaining the clamp until after delivery of the placenta.

Placental cord drainage may, or may not, be in conjunction with other interventions such as routine administration of oxytocic, controlled cord traction (CCT) or maternal effort. Variation in associated interventions such as timing of cord clamping (McDonald 2008; Rabe 2004), application of CCT and timing of administration of uterotonic drugs (Soltani 2010) as well as mode of birth (e.g. instrumental birth) should be borne in mind when evaluating the effects of placental cord drainage on the management of the third stage of labour. Instrumental birth is identified as a risk factor for postpartum haemorrhage (Combs 1991) partly due to the associated complications and longer length of labour and delivery period.

Finally, anecdotal evidence suggests that cord drainage is not usually practised in association with delayed cord clamping. However, it could be argued that delayed cord clamping may reduce the residual blood volume but it seems likely that some blood still remains in the placenta. The extent to which cord drainage affects the management of the third stage of labour needs to be systematically investigated.

Objectives

To assess the specific effect of placental cord drainage on the third stage of labour following vaginal birth, with or without the prophylactic use of oxytocics.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials comparing placental cord drainage with no cord drainage after cord clamping during vaginal birth, in the management of the third stage of labour. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies.

Types of participants

All women who had a vaginal delivery.

Types of interventions

Unclamping the previously clamped and divided umbilical cord and allowing the blood from the placenta to drain freely, compared with no cord drainage. We excluded studies in which CCT was practiced differently between the two arms.

Types of outcome measures

- Incidence of retained placenta

- Manual removal of placenta

- Postpartum haemorrhage

- Postpartum blood loss

- Changes in maternal haemoglobin (Hb) after birth

- Use of blood transfusion

- Maternal pain during third stage

- Length of the third stage of labour

- Fetomaternal haemorrhage

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (February 2010).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

- quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

- weekly searches of MEDLINE;

- weekly searches of EMBASE;

- handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

- weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

For details of additional searching carried out in the previous version of the review, see:Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We attempted to contact authors of published and unpublished articles for more information. We did not apply any language restrictions.

We also considered abstracts for inclusion, if sufficient information was provided.

Data collection and analysis

For the methods used when assessing the trials identified in the previous version of this review, seeAppendix 2.

Additional trials which we considered for this update included Gulati 2001; Jongkolsiri 2009; Navaneethakrishnan 2007; Sharma 2005; Shravage 2007. We used the following methods when assessing the trials identified by the updated search.

Selection of studies

All the review authors independently assessed for inclusion, all the potential studies that were identified as a result of the search strategy.We resolved any disagreement through discussion among the authors.

Data extraction and management

We used a standard form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data independently, using the agreed form. The third review author checked for accuracy and entered the data into Review Manager (RevMan) software (RevMan 2011).

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion.

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

- low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

- high risk of bias (any non random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number); or

- unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determine whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

- low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

- high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

- unclear risk of bias.

(3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We judged studies to be at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding could not have affected the results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

- low risk, high risk or unclear risk of bias for participants;

- low risk, high risk or unclear risk of bias for personnel;

- low risk, high risk or unclear risk of bias for outcome assessors.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. It was planned, where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook. We assessed methods as:

- low risk of bias: where the missing data were less than 20%;

- high risk of bias;

- unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

- low risk of bias (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review had been reported);

- high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes had been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

- unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other sources of bias

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

- low risk of other bias;

- high risk of other bias;

- unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2009). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. We explored the impact of the level of bias by undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion in this update. In future updates, if we identify any cluster‐randomised trials, we will include them in the analyses along with individually randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Dealing with missing data

We intended that the outcome analyses would be treated, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis, i.e. we intended to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial would have been the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect using sensitivity analysis. The attrition rates in all the included studies were well below 20%, the pre‐determined cut‐off point for inclusion. Therefore, no further sensitivity analysis on this basis was required.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. Where there was a substantial heterogeneity (I² statistic greater than 50%), we applied a random‐effects analysis model and we explored the source of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias (see ‘Selective reporting bias’ above), we attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by a sensitivity analysis**.**

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the RevMan software (RevMan 2011). We intended to use fixed‐effect inverse variance meta‐analysis for combining data where trials were examining the same intervention, and where we judged that the trials’ populations and methods were sufficiently similar. Due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity between included studies sufficient to suggest that treatment effects may differ between trials, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

- Cord drainage compared with the non‐cord drainage, in women who had a normal vaginal birth, those who had a vaginal assisted birth, and where the mode of birth was mixed/unknown’.

- Cord drainage compared with the non‐cord drainage in women who had administration of a uterotonic agent, or controlled cord traction (CCT),or both before and those who had it after the sign of separation of the placenta.

- Cord drainage compared with non‐cord drainage in women with and without CCT.

- Cord drainage compared with non‐cord drainage in women who had an early cord clamping and those who had a delayed cord clamping.

We planned to use the following outcomes in subgroup analysis.

- Incidence of retained placenta.

- Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage.

- Postpartum blood loss.

- Use of blood transfusion.

- Length of the third stage of labour.

For fixed‐effect meta‐analyses, we intended to conduct subgroup analyses classifying whole trials by an interaction test. Due to clinical heterogeneity among included studies, we performed random effects meta‐analyses.

For the subgroup analyses, only a limited number of studies were available. We assessed differences between the subgroups by inspection of the subgroups’ CIs; non‐overlapping CIs indicate a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses for aspects of the review that might affect the results, for example, where there was a risk of bias associated with the quality of some of the included trials. We excluded studies with a high risk of bias specially those within the "unclear" or "no" allocation concealment categories for the purpose of the sensitivity analysis.

Results

Description of studies

We identified 12 relevant studies, 11 directly from a search of the above mentioned databases and one through discussion with other investigators who expressed an interest in this area (Razmkhah 1999). We excluded eight studies, some on the basis of lack of appropriate randomisation (Botha 1968; Gulati 2001; Navaneethakrishnan 2007) and inadequate reporting of study despite efforts to obtain further information (Moncrieff 1986) or clinical variation in the application of CCT between the control and intervention groups (Giacalone 2000). The other four were excluded based on further quality assessment and inadequate sequence generation such as the use of alternate birth dates for randomisation (Johansen 1971), alternating allocation (Razmkhah 1999; Terry 1970) and for reporting bias (Thomas 1990) (seeCharacteristics of excluded studies).

Included studies

Three studies involving 1257 women met our inclusion criteria (Jongkolsiri 2009; Sharma 2005; Shravage 2007). They compared women at low risk of postpartum haemorrhage either with or without immediate cord drainage. Two studies included instrumental deliveries however, there were no significant differences in the two groups of intervention and control with regard to the rate of instrumental birth (Jongkolsiri 2009) and induction of labour (Sharma 2005). In the latter study, intravenous Methergine was administered at delivery of the anterior shoulder and CCT was applied in both groups. This was the only study that administered a uterotonic agent before the separation of the placenta. In the other two studies the uterotonic drugs and CCT were applied after signs of placental separation in the third stage of labour. In all studies, the cord was clamped immediately in both groups and in their experimental groups the cord was also immediately unclamped and drained. Sharma 2005 reported the outcomes separately for primigravida and multigravida women but we added them together for the purpose of this meta‐analysis. SeeCharacteristics of included studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

We made efforts to contact the authors of the included studies to obtain further information, but these were unsuccessful except for Jongkolsiri 2009 who confirmed adequacy of randomisation and allocation concealment. Jongkolsiri 2009 appears to be of an adequate quality with a low risk of bias. In the Sharma 2005 and Shravage 2007 studies, we categorised allocation concealments as unclear which can be a source of bias. Due to the nature of studies, none of the studies were blinded. From the published data, there appears to be no major attrition rates of participants.This may be due to the timing of participant recruitment and the interventions being carried out.

Effects of interventions

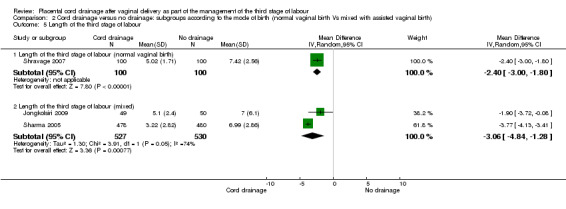

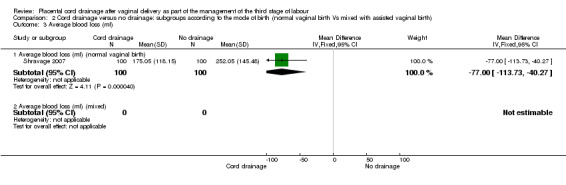

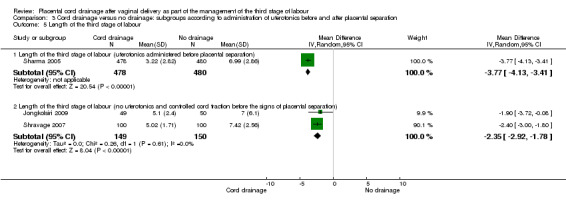

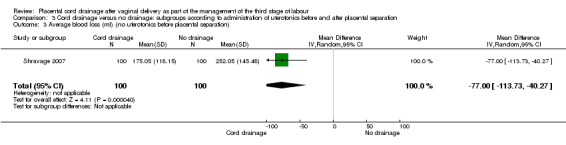

The length of third stage of labour was significantly shorter in the group who had cord drainage (mean difference (MD) ‐2.85 minutes, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐4.04 to ‐1.66; three trials, 1257 women (heterogeneity: T² = 0.87; Chi² P = 17.19, I² = 88%); Analysis 1.6). The average amount of blood loss was also significantly lower in the placental cord drainage group compared with the controls (MD ‐77.00 ml, 95% CI ‐113.73 to ‐40.27; one trial, 200 women; Analysis 1.4).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cord drainage versus no drainage (all), Outcome 6 Length of the third stage of labour.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cord drainage versus no drainage (all), Outcome 4 Average blood loss (ml).

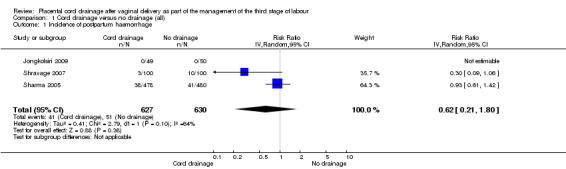

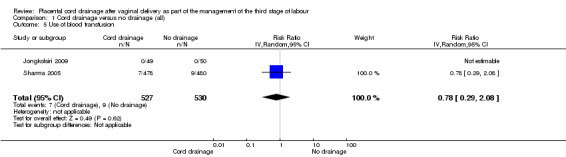

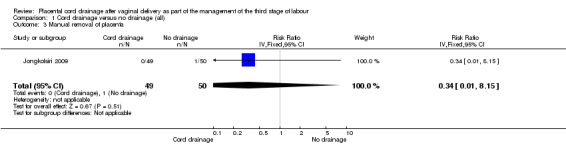

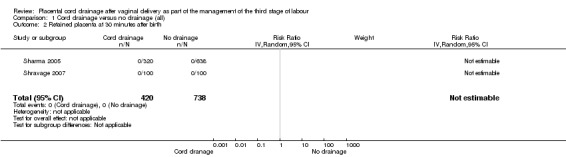

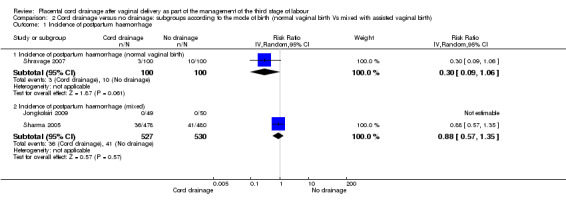

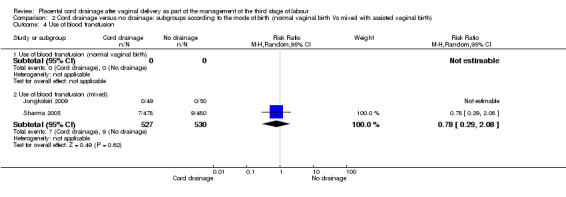

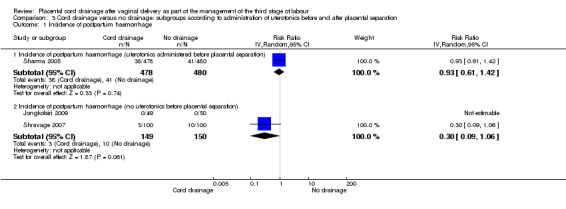

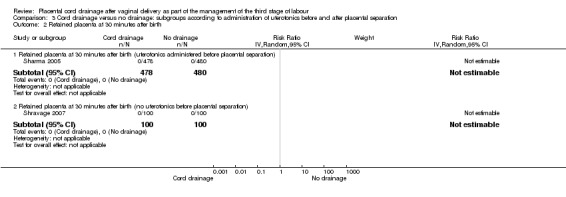

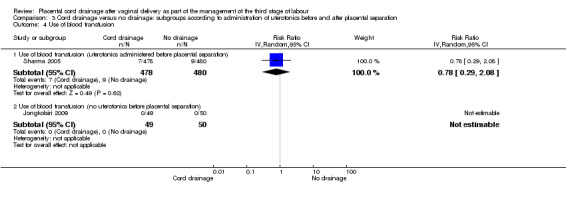

There were no significant differences between the cord drainage and the control groups in the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage greater than 500 ml (average risk ratio (RR) 0.62, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.80; three trials, 1257 women; random‐effects (heterogeneity: T²= 0.42; Chi² P = 0.09; I² = 64%); Analysis 1.1); incidence of blood transfusion (average RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.08; two trials, 1057 women; (heterogeneity not applicable since events were observed only in one study) Analysis 1.5); and manual removal of the placenta (average RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.15; one trial, 99 women; Analysis 1.3). Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth was not observed in any of the included studies, therefore, it was not possible to compare the events; Analysis 1.2. None of the included studies reported fetomaternal transfusion outcome or maternal haemoglobin changes. There were no data relating to maternal pain or discomfort during the third stage of labour.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cord drainage versus no drainage (all), Outcome 1 Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cord drainage versus no drainage (all), Outcome 5 Use of blood transfusion.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cord drainage versus no drainage (all), Outcome 3 Manual removal of placenta.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cord drainage versus no drainage (all), Outcome 2 Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth.

Subgroup analysis

We carried out the following subgroup analyses for the identified outcomes. We did not carry out any interaction tests due to the heterogeneity of the studies and because we used random‐effects tests.

1. Cord drainage compared with non‐cord drainage according to the mode of birth: this included studies in which women had normal vaginal birth and those who reported a mixed mode of birth (assisted and normal vaginal birth)

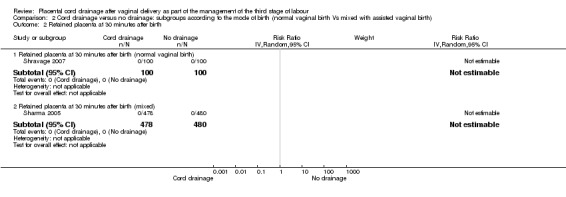

Out of the three included studies, only one (Shravage 2007), exclusively reported on women who had normal vaginal births. Therefore, we analysed the pre‐specified outcomes available for this study to eliminate the potential confounding effects of the instrumental birth on the findings. The overlapping CIs for subgroups with available data showed there were no significant differences between the subgroups in the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage Analysis 2.1 and the length of the third stage of labour Analysis 2.5. For other outcomes there were no sufficient data available to allow comparison between the subgroups (Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to the mode of birth (normal vaginal birth Vs mixed with assisted vaginal birth), Outcome 1 Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to the mode of birth (normal vaginal birth Vs mixed with assisted vaginal birth), Outcome 5 Length of the third stage of labour.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to the mode of birth (normal vaginal birth Vs mixed with assisted vaginal birth), Outcome 2 Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to the mode of birth (normal vaginal birth Vs mixed with assisted vaginal birth), Outcome 3 Average blood loss (ml).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to the mode of birth (normal vaginal birth Vs mixed with assisted vaginal birth), Outcome 4 Use of blood transfusion.

2. Cord drainage compared with non‐cord drainage in women who had administration of an uterotonic agent or CCT, or both, before versus those who had them after the signs of placental separation

Sharma 2005 was the only study that administered a uterotonic drug (methyl‐ergomethrine, intramuscularly) at the birth of the anterior shoulder and applied CCT (it is not fully clear whether CCT was before or after the signs of separation). There were no significant differences in the subgroups with regard to the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage Analysis 3.1 and the length of the third stage of labour Analysis 3.5. For other outcomes, there were not sufficient data to compare the subgroups (Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to administration of uterotonics before and after placental separation, Outcome 1 Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to administration of uterotonics before and after placental separation, Outcome 5 Length of the third stage of labour.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to administration of uterotonics before and after placental separation, Outcome 2 Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to administration of uterotonics before and after placental separation, Outcome 3 Average blood loss (ml) (no uterotonics before placental separation).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to administration of uterotonics before and after placental separation, Outcome 4 Use of blood transfusion.

3. Cord drainage compared with non‐cord drainage in women with and without CCT

All the included studies applied CCT, therefore, it was not possible to carry out this subgroup analysis.

4. Cord drainage compared to non‐cord drainage in women who had an early cord clamping and those who had a delayed cord clamping

All the included studies applied early cord clamping, therefore, it was not possible to carry out this subgroup analysis.

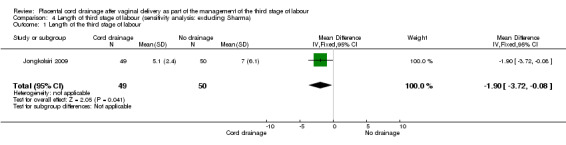

Sensitivity analysis

The outcome for which we performed a sensitivity analysis based on quality assessment, was the length of the third stage of labour. The only study for this outcome which met the criteria (all quality indicators were adequate including allocation concealment) was Jongkolsiri 2009 and it showed a similar result in that the cord drainage reduced the length of the third stage of labour (RR ‐1.90, 95% CI ‐3.72 to ‐0.08; n = 99, one study). It was not possible to carry out a sensitivity analysis for other outcomes due to lack of sufficient data.

Discussion

We identified a small number of studies with a reasonable level of quality for this review. From these, there appears to be a statistically significant reduction in the length of the third stage of labour and a lower blood loss in the cord drainage group compared with the control group.

The length of the third stage of labour remained shorter in women who had cord drainage compared with the controls in the sensitivity analysis (Analysis 4.1) and in the subgroup analyses (Analysis 3.5; Analysis 2.5). The latter may indicate that this effect is independent of the timing of the administration of the uterotonics and of the mode of delivery.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Length of third stage of labour (sensitivity analysis: excluding Sharma), Outcome 1 Length of the third stage of labour.

The reduced length of the third stage of labour and the observed reduction in the amount of blood loss by cord drainage were not translated into a reduction in the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage which is the major concern for the care of mothers during the third stage of labour. This may be due to the small size of available data in this review. In the subgroup analyses separating Sharma 2005 (which included instrumental birth and early administration of uterotonics), an insignificant trend in favour of cord drainage was evident (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 3.1). Due to the limited number of available studies reporting this outcome, further studies with focused designs may be beneficial.

The other issue was the subjectivity of the outcome measurements. Blood loss was mainly objectively measured in the included studies but not all reported the outcome in a standard way to allow a reliable evaluation of effect size. In none of the studies was it possible to blind the involved health professional, to the subject allocation or outcome measurements. This might have an impact on their estimations of factors such as blood loss and whether a manual removal was necessary.

A major confounding factor in such studies could be the variation in practice of the use of uterotonic drugs both in relation to the type of drug used (McDonald 2004) and the timing of its administration (Soltani 2010). These issues might have a significant effect on the duration and successful completion of the third stage of labour. Although in this instance, oxytocin was the only uterotonic drug being used in all the included studies and two out of the three included studies, were clear about not using it as part of the management of the third stage of labour before the signs of placental separation (e.g. lengthening of the placental cord, a gush of blood and increased height of the fundus). The results remained significant when Sharma 2005 (in which uterotonics were used before the placental separation), was excluded from the sensitivity analysis or analysed separately in the subgroup analysis.

Instrumental birth can also be a confounding factor in the management of the third stage of labour due to its potential association with complicated birth or birth canal trauma. Although in our review subgroup analysis of women with normal vaginal birth and those with a mixed model of birth (including assisted vaginal birth), did not change the result in that the cord drainage reduced the length of the third stage of labour.

The timing of cord clamping is also an important factor in the management of third stage of labour, which has been reviewed by McDonald 2008. Delayed cord clamping from the mother's viewpoint is similar to cord drainage and our results are similar in the lack of significant differences in the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage, manual removal of placenta and the need for blood transfusion between the intervention and control groups. However, unlike McDonald 2008, we did observe a significantly shorter length of the third stage of labour and a lower amount of blood loss in the intervention group. Whether these differences are due to the clinical heterogeneity of the interventions and complexity of the interacting effects of the associated components in the available studies in which the third stage of labour is examined, remains unclear. This may indicate that comparison of homogeneous packages of care may be a more appropriate way in evaluating effectiveness than focusing on each component of the care during the third stage of labour, in isolation.

Another important issue to address is the impact of the timing of cord clamping and cutting on the well‐being of the newborn babies. Only one included study, administered a uterotonic drug (Methergine, given intravenously) at delivery of anterior shoulder, the others administered a uterotonic agent after observing the signs of separation of the placenta. Most studies applied CCT mainly after separation of the placenta. In delayed clamping, especially when oxytocic drugs had been administered, there are some concerns about the risk of over‐perfusion of blood to the baby and increased risk of jaundice or hyperbilirubinaemia (McDonald 2008; Saigal 1972). Early clamping may deprive babies of a natural source of extra blood volume, from which they could otherwise benefit. The Hinchingbrooke trial (Rogers 1998) showed a higher mean birthweight of babies in the expectant management group compared with the active management group, which they suggest is probably due to the extra blood received prior to delayed cord clamping.

Finally, it may be argued that the clinical significance of a small statistical reduction in blood loss (about 77 ml) or the reduced length of the third stage of labour (about three minutes) from cord drainage, is open to discussion. Nevertheless, simplicity of this practice and lack of evidence of harm or invasiveness adds to its small benefits observed in this review.

Summary of main results

We identified three studies with an acceptable quality for this review. There appears to be a consistent result in the use of placental cord drainage in terms of a small reduction in the length of the third stage of labour. Although few studies were available, the length of the third stage of labour in the cord drainage group compared with the control group remained consistently lower in the sensitivity analysis where we excluded studies of lower quality or in the subgroup analysis where the only study in which a uterotonic drug was used before the separation of the placenta, was separately analysed.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There are limitations in the nature of the identified studies. One of the major problems encountered in carrying out this review was the variation in methods of reporting the findings; some studies reported mean and standard deviation, some median and range and others proportions. There was also the issue of poor reporting and lack of clarity on how the study was conducted or the nature of the intervention. This made it harder to compare or combine similar outcome measures. Attempts to contact the authors to obtain raw data or an alternative data format for the outcome measures were not always successful, probably due in most cases to the age of the publications.

No retained placenta was reported in the included studies and the incidence of manual removal of the placenta was not significantly different between the intervention and the control groups. The relative rarity of these events may indicate the need for larger study populations for a meaningful comparison.

Although a limited number of studies were available, we observed some statistically positive effects from cord drainage in reducing the length of the third stage of labour, irrespective of the other interventions (e.g. use of uterotonic drugs). This seems to be a good alternative method where delayed cord clamping in which the blood is naturally drained into the neonatal circulation is of concern.

Quality of the evidence

Out of the three included studies, one is of low risk in all the identified sources of bias (Jongkolsiri 2009) while the other two studies were of low risk in sequence generation but unclear about allocation concealment and blinding (Sharma 2005; Shravage 2007). Shravage 2007 also was unclear about attrition bias. In addition, there is a high level of clinical and statistical heterogeneity in the included studies impacting on the quality of evidence.

Potential biases in the review process

In the nature of the study it was not possible to blind the attendants to the intervention and outcomes. Measurement of postpartum haemorrhage is not very accurate and can be biased by the observers. The decision to proceed to manual removal of the placenta is similarly likely to be very subjective. The accepted global definition of the level of postpartum haemorrhage is also debatable. Compared to estimated blood loss, the length of the third stage is likely to be a less biased outcome. Outcomes such as maternal haemoglobin level may be a more reliable measure although practically restricting, therefore not many studies reported this outcome.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There have been no other reviews of this subject. However, delayed cord clamping has a similar result in reducing the volume of blood retained within the placenta before it is expelled from the uterus. The Cochrane review by McDonald 2008 showed no significant differences between early and late cord clamping for postpartum haemorrhage or severe postpartum haemorrhage in any of the five trials (2236 women) which measured this outcome (RR for postpartum haemorrhage 500 ml or more 1.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.96 to 1.55). This indicates that a more physiological approach to the management of the third stage of labour has, at the least, no adverse effect on postpartum haemorrhage.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of this study show small positive effects from cord drainage in reducing the length of the third stage of labour by a few minutes and in reducing the amount of blood loss when compared with those without cord drainage. The observed changes may be of little clinical significance particularly in light of the limited availability of high quality studies.

Implications for research.

This may not be considered a maternity research priority area due to the urgency and importance of other aspects of maternal care with a higher impact on health and well‐being of mothers and babies. However, further large‐scale well designed randomised studies reporting separately for different clinical groups (e.g. vaginal normal birth and assisted birth) may be helpful in relation to the impact of cord drainage on the management of the third stage of labour. The impact of cord drainage at caesarean section is also of interest. Important outcomes should include maternal haemoglobin and indicators of maternal satisfaction.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 August 2011 | New search has been performed | Five studies previously awaiting classification have now been evaluated: three new studies have been included (Jongkolsiri 2009; Sharma 2005; Shravage 2007) and two have been excluded (Gulati 2001; Navaneethakrishnan 2007). Search updated further on 3 August 2011 and one new report added to Studies awaiting classification for assessment and inclusion in the next update.On further scrutiny, the authors decided that two previously included studies (Giacalone 2000; Razmkhah 1999) do not meet the criteria for inclusion and have therefore excluded them from this update ‐ seeDifferences between protocol and review and Characteristics of excluded studies. The conclusions have not changed.A new (additional) reference was added to the background (Farrar 2011). |

| 3 August 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Two new authors helped to prepare this update. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2004 Review first published: Issue 4, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 July 2009 | Amended | Search updated. Four reports added to Studies awaiting classification (Jongkolsiri 2009; Navaneethakrishnan 2007; Sharma 2005; Shravage 2007).The term "spontaneous" was excluded from the titleAll types of vaginal deliveries are now included in the review (e.g. studies including instrumental birth) |

| 20 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Fiona Dickinson's contribution to the development of the protocol and the first version of this review. We are also grateful to Ian Symonds for his comments on the first review.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by four peers (an editor and three referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

Authors searched the Cumulative Index in Nursing and Allied Health Library (CINAHL) (1982 to December 2004) using the search strategy:

- exp Labor Stage, Third/

- (third adj4 stage).mp.

- ("3" adj4 stage).mp.

- (3rd adj4 stage).mp.

- exp Postpartum Hemorrhage/pc [Prevention and Control]

- (postpartum hemorrhage or postpartum haemorrhage).ti,ab.

- (post‐partum haemorrhage or post‐partum hemorrhage).ti,ab.

- exp Placenta, retained/pc [Prevention and Control]

- (cord adj4 drain$).mp.

- exp Drainage/

- (placenta$ adj4 drain$).mp.

- or/1‐8

- or/9‐11

- 12 and 13

Authors also used a similar strategy to search the National Research Register in December 2004.

Appendix 2. Methods used to assess trials included in previous versions of this review

The quality of the studies was assessed by two individual review authors and discussed and agreed within the review team.

We collected the data using a preformatted extraction sheet. The tabulated information included quality of studies and characteristics such as authors, years, methods, participants, interventions and outcome results. We attempted to minimise the sources of systematic bias including selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias and detection bias. Quality scores for concealment of allocation were assigned using the criteria described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Clarke 2003). As a criterion to assess validity, we allocated a grade to each trial on the basis of allocation concealment: A = adequate, B = unclear, C = inadequate, and D = not used. Trials graded as A or B were included in the analysis.

While it is not possible to blind participants or professionals to cord drainage, we assessed studies in terms of whether outcome assessments were blind to researchers who analysed the study. Given that the approach to handling losses of participants (e.g. withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations) has the potential to bias results, and that losses are often inadequately reported, we were cautious about implicit accounts of such details.

For all data analyses in this review, we entered data based on the principle of intention to treat. To be included in comparisons, outcome data had to be available for at least 80% of those who were randomised. Statistical analysis was performed using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2003). The results were presented as relative risks for binary outcomes, or weighted mean difference for continuous outcome measures, with 95% confidence intervals. Where the data were available from two or more studies, we assessed the heterogeneity of the trials using the I² statistic. If the trials were sufficiently similar, we performed a fixed‐effext meta‐analysis. If there were differences between the trials (values more than 50% indicate substantial heterogeneity), we investigated the causes of heterogeneity and if they were likely to lead to differences in their treatment effects, we used a random‐effects meta‐analysis(Higgins 2003).

Originally we intended to do analyse sensitivity by including:

- allocation concealment other than A (adequate) and B (unclear);

- studies with follow‐up rate of less than 80%;

- quasi‐randomised studies.

RESULTS:There were no data for changes in maternal haemoglobin, other than one study giving the proportion of women with a change of 3 g/dl,

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Cord drainage versus no drainage (all).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage | 3 | 1257 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.21, 1.80] |

| 2 Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth | 2 | 1158 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Manual removal of placenta | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.01, 8.15] |

| 4 Average blood loss (ml) | 1 | 200 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐77.0 [‐113.73, ‐40.27] |

| 5 Use of blood transfusion | 2 | 1057 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.29, 2.08] |

| 6 Length of the third stage of labour | 3 | 1257 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.85 [‐4.04, ‐1.66] |

Comparison 2. Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to the mode of birth (normal vaginal birth Vs mixed with assisted vaginal birth).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage | 3 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage (normal vaginal birth) | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.09, 1.06] |

| 1.2 Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage (mixed) | 2 | 1057 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.57, 1.35] |

| 2 Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth | 2 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth (normal vaginal birth) | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth (mixed) | 1 | 958 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Average blood loss (ml) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Average blood loss (ml) (normal vaginal birth) | 1 | 200 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐77.0 [‐113.73, ‐40.27] |

| 3.2 Average blood loss (ml) (mixed) | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Use of blood transfusion | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Use of blood transfusion (normal vaginal birth) | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.2 Use of blood transfusion (mixed) | 2 | 1057 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.29, 2.08] |

| 5 Length of the third stage of labour | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Length of the third stage of labour (normal vaginal birth) | 1 | 200 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.40 [‐3.00, ‐1.80] |

| 5.2 Length of the third stage of labour (mixed) | 2 | 1057 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.06 [‐4.84, ‐1.28] |

Comparison 3. Cord drainage versus no drainage: subgroups according to administration of uterotonics before and after placental separation.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage | 3 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage (uterotonics administered before placental separation) | 1 | 958 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.61, 1.42] |

| 1.2 Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage (no uterotonics before placental separation) | 2 | 299 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.09, 1.06] |

| 2 Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth | 2 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth (uterotonics administered before placental separation) | 1 | 958 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Retained placenta at 30 minutes after birth (no uterotonics before placental separation) | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Average blood loss (ml) (no uterotonics before placental separation) | 1 | 200 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐77.0 [‐113.73, ‐40.27] |

| 4 Use of blood transfusion | 2 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Use of blood transfusion (uterotonics administered before placental separation) | 1 | 958 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.29, 2.08] |

| 4.2 Use of blood transfusion (no uterotonics before placental separation) | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Length of the third stage of labour | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Length of the third stage of labour (uterotonics administered before placental separation) | 1 | 958 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.77 [‐4.13, ‐3.41] |

| 5.2 Length of the third stage of labour (no uterotonics and controlled cord traction before the signs of placental separation) | 2 | 299 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.35 [‐2.92, ‐1.78] |

Comparison 4. Length of third stage of labour (sensitivity analysis: excluding Sharma).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Length of the third stage of labour | 1 | 99 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.90 [‐3.72, ‐0.08] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Jongkolsiri 2009.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation using code kept in a sealed envelope. More clarification on sequence generation and allocation concealment was provided by the authors. | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | 100 women (50 in each group) with normal vaginal delivery and instrumental delivery, vertex presentation, singleton term pregnancy. Exclusions: 1 case of placenta succenturiata, preterm delivery, maternal and medical complications, fetal compromise or abnormality, post‐term, premature rupture of membranes, APH, history of PPH, previous CS and fetal death.Mixed mode of delivery including normal vaginal and instrumental birth. | |

| Interventions | Cord unclamped and drained immediately after cutting in study group. Cord traction after signs of separation to deliver placenta by Brand‐Andrew manoeuvre and IV Methergine after delivery of placenta in both groups. | |

| Outcomes | Duration of the third stage. Retained placenta (> 30 minutes) and PPH (> 500 ml), the need for blood transfusion. | |

| Notes | There was no statistically significant difference between the control and intervention groups with regard to the mode of delivery (instrumental delivery and normal vaginal delivery).One of researchers was blinded, however, the obstetrician and women were not blinded.Blood drained from the placental cord in the intervention group was measured by scaled container. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Women were randomised to the study group or the control group according to the code kept in a sealed envelope. The author confirmed that sequence generation was by computer random number generator. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Author confirmed that "after randomization the code was kept in sequentially numbered envelopes, the envelopes were opaque and sealed". |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Partial blinding: 1 researcher who analysed the data, was blinded. However, the obstetrician and women were not blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 1 case of placenta succenturiata was excluded. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk |

Sharma 2005.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, using computer‐generated numbers. | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | 958 women (478 in the intervention and 480 in the control group) with normal vaginal delivery and instrumental delivery, vertex presentation, singleton pregnancy. Preterm births included. Exclusions not otherwise specified.Mixed mode of birth including normal vaginal and instrumental birth. | |

| Interventions | Cord unclamped and drained immediately after cutting in study group. IM Methyergometrine with anterior shoulder and cord traction for delivery of placenta in both groups. Blood loss from episiotomy excluded.In follow‐up correspondence, Sharma confirmed that CCT was carried out in both groups. | |

| Outcomes | Duration of the third stage of labour, PPH, blood transfusion. There were no cases of retained placenta in the groups. The results for all outcomes are separately reported for the primigravida and multigravida women. | |

| Notes | Most cases were spontaneous deliveries. The 2 groups were similar in the rate of spontaneous birth and instrumental deliveries. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomised using computer‐generated numbers. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | No explanation is provided to indicate allocation concealment. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No evidence of blinding. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The data appears to be complete with no withdrawal. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The data seem to be reported clearly and consistently. |

| Other bias | Low risk |

Shravage 2007.

| Methods | RCT. Randomisation was by computer‐generated table. | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | 200 women (100 in each group) with spontaneous normal vaginal delivery. Exclusions were preterm, multiples, anaemia (Hb < 7 g/dl), polyhydramnios, large baby, APH, induction, instrumental delivery and known coagulation disorders.Only vaginal normal birth. | |

| Interventions | Immediate clamping and division of the cord for both groups. Cord unclamped and drained immediately after cutting in study group. In the control group, the placental end of cut umbilical cord remained clamped. Controlled cord traction after signs of separation and IV Methergin after delivery of placenta in both groups. | |

| Outcomes | Mean duration of the third stage of labour (minutes). Average blood loss, excluding episiotomy loss. Incidence of PPH. Number of cases who required additional uterotonic drugs (oxytocin or Prostadin). Number of retained placenta (none in each group). Blood transfusion (none required). | |

| Notes | Blood loss was objectively measured. Blood loss from episiotomy excluded. Women were randomised after the second stage of labour. Poor reporting style, it is assumed that there were 100 women in each arm although the article does not specify the number of participants in each group and no withdrawal is reported. Table 1 is missing. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation by computer‐generated table. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | This is not explained in the text, probably not. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No indication of blinding the participants or the clinicians, more likely not blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | There does seem to be a full compliance. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Table 1 is missing, which may indicate limitation in quality standards. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Botha 1968 | This was not a randomised controlled trial. "A series of cases including 60 unselected, consecutive normal deliveries were divided to two groups.." |

| Giacalone 2000 | CCT was practiced differently between the two arms ‐ therefore this study does not meet the inclusion criteria. It appears that the intervention group had cord drainage along with CCT but the control group had spontaneous expulsion of placenta after observing the signs of separation. |

| Gulati 2001 | This was not indicated as being a randomised controlled trial. Although this study shows a reduced length of the third stage of labour and less amount of blood loss in the cord drainage group compared with the control group, there is no indication of a randomised allocation of participants to each group.The methods describe very briefly: "The study was carried out on 200 pregnant women...admitted in the labour ward..." |

| Johansen 1971 | This was a quasi‐randomised study, as methods describes: "200 women of comparable age, parity...were studied...the control group comprised 110 women born on odd dates and the study group comprised of 90 women born on even dates." |

| Moncrieff 1986 | Inadequate reporting; not enough details reported to evaluate the quality of the research and randomisation process/not possible to contact the authors for more details. |

| Navaneethakrishnan 2007 | The main reasons include inadequate reporting being an abstract and inclusion of caesarean section deliveries. In addition, the main objective of this study was to determine whether placental cord drainage reduces the size of fetomaternal transfusion in rhesus negative women, no other outcomes were reported. |

| Razmkhah 1999 | This was a quasi‐randomised study as it is described in the text: "This study is a semi‐experimental investigation in which 147 women in labor were placed randomly in two groups: experimental (placental end of umbilical cord open) and control (placental end of umbilical cord closed)". "[No more information about randomisation has been provided.]" |

| Terry 1970 | This was a quasi‐randomised study. Cases were allocated alternately. |

| Thomas 1990 | The main issue that undermines the reliability of this paper includes a series of reporting bias. The authors initially explain that all participants had early cord clamping, although data in table 1, indicate that almost half of all participants had cord clamping after cord pulsation ceased. The other confusing matter is how they have labelled the intervention group as "late cord clamping" and the control group as "early clamping" (table 1). The timing of cord clamping is a confounding factor. In addition, the cord drainage group has not exclusively had delayed cord clamping, there seems to be some confusion in defining the groups in the study. Also, the outcomes of interest have not reported (PPH) or defined (e.g. manual removal of placenta or retained placenta) in a standard way. |

Differences between protocol and review

We excluded studies in which controlled cord traction (CCT) were practiced differently between the two arms.

A subgroup according to the timing of cord clamping has been added.

Contributions of authors

Hora Soltani and Fiona Dickinson prepared the first drafts of the protocol and the review. It was then revised by Ian Symonds for his comments. The final versions were discussed and agreed within the team.

For this update, David Hutchon, Thomas Poulose and Hora Soltani independently evaluated the additional studies for inclusion and extracted the relevant data. Hora Soltani, updated the text and re‐analysed the data in light of the new additions. The updated version was then commented by the other two authors. The final version was discussed and agreed within the review team.

Sources of support

Internal sources

- Sheffield Hallam University, UK.

External sources

- No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

David Hutchon: I have written a number of published articles and letters explaining that cord clamping before cessation of the placental circulation is an intervention with some evidence of harm.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Jongkolsiri 2009 {published and unpublished data}

- Jongkolsiri P, Manotaya S. Placental cord drainage and the effect on the duration of third stage labour, a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 2009;92(4):457‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sharma 2005 {published data only}

- Sharma JB, Pundir P, Malhotra M, Arora R. Evaluation of placental drainage as a method of placental delivery in vaginal deliveries. Archives of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2005;271(4):343‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shravage 2007 {published data only}

- Shravage JC, Silpa P. Randomized controlled trial of placental blood drainage for the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India 2007;57(3):214‐6. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Botha 1968 {published data only}

- Botha MC. The management of the umbilical cord in labour. South African Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1968;6:30‐3. [Google Scholar]

Giacalone 2000 {published data only}

- Giacalone PL, Vignal J, Daures JP, Boulot P, Hedon B, Laffargue F. A randomised evaluation of two techniques of management of the third stage of labour in women at low risk of postpartum haemorrhage. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2000;107:396‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gulati 2001 {published data only}

- Gulati N, Chauhan MB, Mandeep R. Placental blood drainage in management of third stage of labour. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India 2001;51(6):46‐8. [Google Scholar]

Johansen 1971 {published data only}

- Johansen J, Schacke E, Sturup AG. Feto‐maternal transfusion and free bleeding from the umbilical cord. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1971;50:193‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moncrieff 1986 {published data only}

- Moncrieff D, Parker‐Williams J, Chamberlain GVP. Placental drainage and fetomaternal transfusion [letter]. Lancet 1986;2:453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Navaneethakrishnan 2007 {published data only}

- Navaneethakrishnan R, Anderson A, Holding S, Atkinson C, Lindow SW. A randomised controlled trial of placental drainage to reduce feto‐maternal transfusion [abstract]. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2007;27(Suppl 1):S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Razmkhah 1999 {published data only}

- Razmkhah N, Kordi M, Yousophi Z. The effects of cord drainage on the length of third stage of labour. Scientific Journal of Nursing and Midwifery of Mashad University 1999;1:10‐4. [Google Scholar]

Terry 1970 {published data only}

- Terry M. A management of the third stage to reduce feto‐maternal transfusion. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth 1970;77:129‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thomas 1990 {published data only}

- Thomas IL, Jeffers TM, Brazier JM, Burt CL, Barr KE. Does cord drainage of placental blood facilitate delivery of the placenta?. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1990;30:314‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Navaneethakrishnan 2010 {published data only}

- Navaneethakrishnan R, Anderson A, Holding S, Atkinson C, Lindow SW. A randomised controlled trial of placental cord drainage to reduce feto‐maternal transfusion. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2010;149:27‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Clarke 2003

- Clarke M, Oxman AD. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.2.0. The Cochrane Library 2003, issue 2.

Combs 1991

- Combs CA, Murphy EL, Laros RK Jr. Factors associated with postpartum hemorrhage with vaginal birth. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1991;77(1):69‐76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cunningham 2010

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, Spong CY. William's Obstetrics. 23rd Edition. London: McGraw Hill, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Farrar 2011

- Farrar D, Airey R, Law G, Tuffnell D, Cattle B, Duley L. Measuring placental transfusion for term births: weighing babies with cord intact. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 2011;118:70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fraser 2009

- Fraser DM, Cooper MA. Myles Textbook for Midwives. 15th Edition. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Gyte 1994

- Gyte GML. Evaluation of the meta‐analyses on the effects, on both mother and baby, of the various components of ‘active’ management of the third stage of labour. Midwifery 1994;10:183‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Herman 1993

- Herman A, Weinraub Z, Bukovsky I, Arieli S, Zabow P Caspi E, et al. Dynamic ultrasonographic imaging of the third stage of labor: new perspectives into third‐stage mechanisms. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1993;168(5):1496‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2009

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 [updated September 2009]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

McDonald 2004

- McDonald SJ, Abbott JM, Higgins SP. Prophylactic ergometrine‐oxytocin versus oxytocin for the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000201.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McDonald 2008

- McDonald SJ, Middleton P. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping at birth of term infants on mother and baby outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004074.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rabe 2004

- Rabe H, Reynolds GJ, Diaz‐Rosello JL. Early versus delayed umbilical cord clamping in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003248.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2011 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

Rogers 1998

- Rogers J, Wood J, McCandlish R, Ayers S, Truesdale A, Elbourne D. Active versus expectant management of third stage of labour: the Hinchingbrooke randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1998;351:693‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saigal 1972

- Saigal S, O'Neill A, Surainder Y. Chuna L, Usher R. Placental transfusion and hyperbilirubinemia in the premature. Pediatrics 1972;49:406‐19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sharma 1995

- Sharma JB, Sharma WA, Newman MRB, Smith RJ. Evaluation of placental drainage at caesarean section as method of placental delivery. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1995;15:237‐9. [Google Scholar]

Soltani 20005a

- Soltani H, Dickinson F, Leune TN. The effect of placental cord drainage in the third stage of labour on fetomaternal transfusion: A systematic review. Evidence Based Midwifery 2005;3(2):64‐8. [Google Scholar]

Soltani 2010

- Soltani H, Hutchon DR, Poulose TA. Timing of prophylactic uterotonics for the third stage of labour after vaginal birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006173.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wood 1997

- Wood J, Rogers J. The third stage of labour. In: Alexander J, Levy V, Roth C editor(s). Midwifery practice: core topics 2. London: MacMillan Press Ltd, 1997. [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Soltani 2005

- Soltani H, Dickinson F, Symonds I. Placental cord drainage after spontaneous vaginal delivery as part of the management of the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004665.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]