Clotiapine for acute psychotic illnesses (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

Acute psychotic illnesses, especially when associated with agitated or violent behaviour, require urgent pharmacological tranquillisation or sedation. Clotiapine, a dibenzothiazepine neuroleptic, is being used for this purpose in several countries.

Objectives

To estimate the effects of clotiapine when compared to other 'standard' or 'non‐standard' treatments for acute psychotic illnesses in controlling disturbed behaviour and reducing psychotic symptoms.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Register (April 2004).

We updated this search in July 2012 and added the results to the awaiting classification section of the review.

Selection criteria

The review included randomised clinical trials comparing clotiapine with any other treatment for people with acute psychotic illnesses.

Data collection and analysis

Relevant studies were selected for inclusion, their quality was assessed and data extracted. Data were excluded where more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow up. For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous outcomes, endpoint data were preferred to change data. Non‐skewed data from valid scales were summated using a weighted mean difference (WMD).

Main results

We identified five relevant trials. None compared clotiapine with placebo, but control drugs were either antipsychotics (chlorpromazine, perphenazine, trifluoperazine and zuclopenthixol acetate) or benzodiazepines (lorazepam).Versus the antipsychotics, the results for 'no important global improvement' did not suggest clotiapine to be superior, or inferior, to chlorpromazine, perphenazine, or trifluoperazine (n = 83, 3 RCTs, RR 0.82 CI 0.22 to 3.05, I‐squared 58%). Use of clotiapine when compared with chlorpromazine did change the proportion of people ready for hospital discharge by the end of the study (n = 49, 1 RCT, RR 1.04 95%CI 0.96 to 2.12). Overall, attrition rates were low. No significant difference was found for those allocated to clotiapine compared with people randomised to other antipsychotics (n = 121, RR 2.26 95%CI 0.40 to 13). Weak data suggests that clotiapine may result in less need for antiparkinsonian treatment compared with zuclopenthixol acetate (n = 38, RR 0.43 95%CI 0.02 to 0.98). Compared with lorazepam, clotiapine, when used to control aggressive/violent outbursts for people already treated with haloperidol, did not significantly improve mental state (WMD ‐3.36 95%CI ‐8.09 to 1.37). We could not pool much data due to skew or inadequate presentation of results. Economic outcomes and satisfaction with care were not addressed.

Authors' conclusions

We found no evidence to support the use of clotiapine in preference to other 'standard' or 'non‐standard' treatments for management of people with acute psychotic illness. All trials in this review have important methodological problems. We do not wish to discourage clinicians from using clotiapine in the psychiatric emergency, but well‐designed, conducted and reported trials are needed to properly determine the efficacy of this drug.

[Note: the three citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Keywords: Humans, Acute Disease, Antipsychotic Agents, Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use, Dibenzothiazepines, Dibenzothiazepines/therapeutic use, Psychotic Disorders, Psychotic Disorders/drug therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Clotiapine for acute psychotic illnesses

Clotiapine is an antipsychotic drug and is currently used in the management of acute psychotic symptoms in Argentina, Belgium, Israel, Italy, Luxemburg, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland and Taiwan. This review highlights limited evidence for the effects of clotiapine compared with other drugs also used in this emergency situation.

Background

People suffering from psychotic illnesses such as schizophrenia, mania or brief psychotic episodes may interpret and perceive the world in a way that others do not comprehend. At times, unusual beliefs and experiences can cause severe anxiety and lead people to harm themselves (Hu 1991; Axelsson 1992) or others (Krakowski 1999; Taylor 1985; Taylor 1998). These events, though rare, are of major concern to carers. A French survey in the Emergency Department of a general hospital showed agitated incidents to be 0.56% of total admissions (Moritz 1999), although these were mostly due to substance misuse. A Finnish cohort study (Tiihonen 1997) also underlined the fact that criminal offences are positively related with substance‐induced psychosis and schizophrenia. Both studies underline that psychosis alone plays only a small role in the generation of agitated or violent behaviour, but it is a risk factor, especially when 'acute' symptoms are present.

Acute psychosis requires psychological and pharmacological treatment. When agitation or aggression is present, the need for treatment becomes urgent and various drug regimens are used in emergency situations. Clinical practice varies. A combination of lorazepam and haloperidol, or lorazepam alone (Hughes 1999), haloperidol alone (Chouinard 1993) and flunitrazepam (Dorevitch 1999) are a few examples. One survey from the USA (Binder 1999) questioned the Medical Directors of 20 Emergency Rooms and found their preferred drug management of aggressive people to be a haloperidol‐lorazepam mixture (Table 1). In 1993, a similar UK survey of clinicians' preferences found chlorpromazine to be the most common choice (Cunnane 1994). A survey of emergency prescribing in a General Psychiatric Hospital in South London showed that rapid medical tranquillisation had to be used 102 times over a period of 160 days (Pilowsky 1992). Eight different drugs were used (Table 2), amongst which diazepam, haloperidol and droperidol were the most favoured. An unpublished survey of the Emergency Rooms in Rio de Janeiro (Huf 2002a) found that 70‐100 people per week were given emergency intramuscular sedation for severe agitation/aggression due to suspected psychotic illnesses (catchment population estimated to be 3.5m). In this case the favoured treatment was a haloperidol‐promethazine mixture (Table 3). Although these studies do focus mostly on violent behaviour, they illustrate the many different pharmacological ways of handling such episodes. It is likely that there are an equal number of methods used in the urgent management of non‐violent agitation associated with positive psychotic symptoms.

1. Survey of Medical Directors of 20 Emergency rooms in the USA.

| Favoured drug regime | Number |

|---|---|

| haloperidol + lorazepam +/‐ benztropine | 11 |

| droperidol | 4 |

| benzodiazepine (unspecified) alone | 3 |

| droperidol + lorazepam + diphenhydramine | 1 |

| haloperidol + benztropine | 1 |

2. Drugs for rapid tranquillisation in London survey.

| Drug of choice | Mean dose (range) |

|---|---|

| diazepam* | 27 (10‐80) |

| haloperidol | 22 (10‐60) |

| chlorpromazine | 162 (50‐400) |

| droperidol | 14 (10‐20) |

| paraldehyde | U/K |

| amytal | U/K |

| lorazepam | U/K |

| nitrazepam** | U/K |

| * most frequent ** least frequent |

3. Preferred medication for rapid tranquillisation in Rio de Janeiro.

| Drug of choice | Mean dose (range) | Frequency of use |

|---|---|---|

| haloperidol + promethazine | 5 (2.5‐10) + 50 (25‐100) | 61% |

| haloperidol + promethazine + diazepam | 5 (2.5‐10) + 50 (25‐100) + 10 | 15% |

| diazepam | 10 | 9% |

| haloperidol + promethazine + chlorpromazine | 5 + 50 + 25 | 7% |

| chlorpromazine + diazepam + promethazine | 25 + 10 + 50 | 1% |

| chlorpromazine + promethazine | 25 + 50 | 1% |

| chlorpromazine | 25 | 1% |

| diazepam + promethazine | 10 + 50 | 1% |

| haloperidol + diazepam | 5 + 10 | 1% |

| promethazine | 50 | 1% |

Ideally, drugs used in urgent treatment of acute psychosis should have the following properties: a swift onset of effect, good tranquillizing or sedative properties, antipsychotic effect, and minimal or no adverse effects. Clotiapine (Clothiapine, Clotiapina, Entumin(e), Etumine, Etomina, Etomin) has been used in acute psychiatric emergencies since the late 1960s when it was first marketed by Wander Laboratories (now Novartis Pharma). Clotiapine is an antipsychotic with a rapid onset of action and a strong sedative effect, comparable to that of zuclopenthixol acetate, but with fewer extrapyramidal side effects (Uys 1996). It is used in Argentina, Belgium, Israel, Italy, Luxemburg, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland and Taiwan. Novartis Pharma state that it is indicated for management of acute or exacerbations of chronic schizophrenia, bipolar disorder especially mania, other forms of acute psychotic illnesses, agitation of endogenous or exogenous (drugs, alcohol) cause, panic, inner uneasiness, drug withdrawal symptoms, states of depersonalisation, hyperactivity and sleep disorder. Unfortunately we have not managed to find data on the extent of its use in these situations.

Technical background of clotiapine Clotiapine, 2‐chloro‐11‐(4‐methyl‐1‐piperazinyl)dibenzo[b,f][1,4]thiazepine, is a dibenzothiazepine neuroleptic which has general properties similar to those of the phenothiazines, i.e. chlorpromazine. Lately, there has also been some interest in possible clozapine‐like properties (Lokshin 1998). Clotiapine down‐regulates cortical 5HT2‐receptors, blocks 5HT3‐receptors and has been shown to have high affinity for 5‐HT6 and 5‐HT7 receptors. Its ratio of D2 to 5HT2 blockade is similar to that of clozapine and, in the rat retinal model clotiapine seems to act as an antagonist of the D4‐receptor (Lokshin 1998). There is an oral form (40 mg) and an injectable form (10mg) of clotiapine for intramuscular (IM) or intravenous (IV) use. Dose for acute psychosis is usually between 120 mg and 200 mg/day, but can be as high as 360 mg/day. Currently, the cost of medication with clotiapine in Switzerland is 0.55 Swiss Francs (˜ £0.20) for one oral dose (40 mg) and 3.40 Swiss Francs (˜ £1.30) for one parenteral dose (10 mg).

Objectives

To estimate the effects of clotiapine, including its cost‐effectiveness, when compared to other 'standard' or 'non‐standard' treatments of acute psychotic illness in controlling acutely disturbed behaviour and reducing psychotic symptoms in those with schizophrenia like illnesses.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials were included. Trials that were described as 'double‐blind', but that did not mention whether the study was randomised, were included in a sensitivity analysis. If there was no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see 'Types of outcome measures') when these studies were added, then they were included in the final analysis. If there was a substantive difference, only clearly randomised trials were utilised and the results of the sensitivity analysis described in the text. Quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week, were excluded.

Types of participants

This includes any people with acute psychotic illnesses such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, affective disorders such as the manic phase of bipolar disorder or a brief psychotic episode, irrespective of age and sex. We also included those whose agitation was linked to drug or alcohol misuse ‐ but this was a post hoc decision. After seeing the studies we decided to include this participant group as data were available for mixed groups of people with psychosis due to functional mental illness or substance misuse, or both (see Discussion). We excluded studies focusing solely on those with agitation or aggression due to substance misuse and not psychosis. For the purposes of this review, we defined 'acute' as where authors of trials refer to the majority of participants as experiencing an 'acute illness/relapse/exacerbation' or phrases that imply that positive symptoms of the illness (such as delusions, hallucinations, formal thought disorders, motor over activity) have recently appeared or shown exacerbation.

Types of interventions

1. Clotiapine: any dose, given orally, or by intramuscular injection against one or more of the following:

2. Standard medication: drug treatments that fit with normal 'custom and practice'. This may involve increasing the dose of standard medication or the addition of another 'standard' psychotropic drug, such as an antipsychotic, an anxiolytic (benzodiazepine or other) or a mood stabiliser.

3. Non‐standard medication: drug treatments which are being trialed as a new type of intervention.

4. Placebo.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes were classified in seven categories detailed below and were categorised as.

1. Behaviour 1.1 Tranquillisation (feeling of calmness and/or calm, non‐sedated behaviour)* 1.2 Aggression* 1.3 Self‐harm, including suicide 1.4 Injury to others* 1.5 Use of further doses of medication 1.6 Clinically important improvement in self care, or degree of improvement in self care 1.7 Compulsory administrations of treatment**

2. Sedation (sleepiness and drowsiness)*

3. Symptoms 3.1 Clinically important reduction of symptoms as defined by each study** 3.2 Any reduction in severity of symptoms 3.3 Increase in symptoms 3.4 Degree of change in severity of symptoms

4. Adverse effects 4.1 Incidence of adverse effects, general or specific 4.2 Leaving the study early 4.3 Measured acceptance of treatment** 4.4 Use of antiparkinsonian treatment 4.5 Sudden and unexpected death

5. Hospital and service outcome 5.1 Hospitalisation of people in the community 5.2 Duration of hospital stay** 5.3 Severity of symptoms when dismissed from hospital (was readmission needed in the month after?) 5.4 Changes in hospital status (for example, changes from informal care to formal detention in care, changes of level of observation by ward staff and use of secluded nursing environment)** 5.5 Changes in services provided by community teams

6. Satisfaction with care 6.1 Recipient of care** 6.2 Informal care givers* 6.3 Professional carers

7. Economic outcomes

We divided outcomes into immediate (within two hours), short term (>2 hours ‐ 24 hours) and medium term (>24 hours ‐ two weeks).

* Primary outcomes for immediate and short term. ** Primary outcomes for medium term.

Search methods for identification of studies

1. 2004 Search 1.1. We searched The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's study based register (April 2004) using the phrase:

[((*clotiapin* OR *clothiapin* OR *etumin* OR *etomin *OR *2159*) in REFERENCE) and (clot* in STUDY)]

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

2. 2012 Search: Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (July 2012)

The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register using the phrase

*clotiapin* OR *clothiapin* OR *etumin* OR *etomin *OR *2159*

The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group’s Trials Register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, handsearches and conference proceedings (see Group Module). Incoming trials are assigned to relevant existing or new review titles.

3. For previous searches see Appendix 1

Data collection and analysis

1. Study selection Simone Carpenter and Michael Berk independently inspected citations identified in the search. For the update, John Rathbone independently inspected and selected papers. Potentially relevant abstracts were identified and full papers ordered and reassessed for inclusion and methodological quality. Once we had obtained the full reports, we resolved disputes over whether studies met the inclusion criteria by discussion.

2. Assessment of quality We allocated trials to three quality categories, as described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Clarke 2003), by all reviewers working independently.. When disputes arose as to which category a trial was allocated, we attempted to resolve them by discussion. When this was not possible and further information was necessary to clarify into which category to allocate the trial, data were not entered and the trial was allocated to the list of those awaiting assessment. We included trials only in Categories A or B in the review.

3. Data management 3.1 Data extraction We extracted data independently and where further clarification was needed we contacted the authors of trials to provide us with the missing data.

3.2 Intention to treat analysis We excluded data from studies where more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow up (this does not include the outcome of 'leaving the study early'). In studies with less than 50% dropout rate, people leaving early were considered to have had the negative outcome, except for the event of death. Regarding the outcomes of 'aggression', 'self harm' and 'harm to others', as they are major risks of non‐treated acute psychotic illness, we considered 5% of the people leaving the study early to have had a negative outcome.

We analysed the impact of including studies with high attrition rates (25‐50%) in a sensitivity analysis. If inclusion of data from this latter group did result in a substantive change in the estimate of effect, we did not add their data to trials with less attrition, but presented them separately.

4. Data analysis 4.1 Binary data For binary outcomes we calculated a standard estimation of the random effects risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). We also calculated the weighted number needed to treat statistic (NNT), and its 95% confidence interval (CI). If heterogeneity was found (see section 5) we used a random effects model.

4.2 Continuous data 4.2.1 Skewed data: continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, the following standards are applied to all data before inclusion: (a) standard deviations and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable from the authors; (b) when a scale started from the finite number zero, the standard deviation, when multiplied by two, was less than the mean (as otherwise the mean was unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution, Altman 1996); (c) if a scale started from a positive value (such as PANSS which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above was modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and end point and these rules can be applied to them. When continuous data are presented on a scale which includes a possibility of negative values (such as change on a scale), there is no way of telling whether data are non‐normally distributed (skewed) or not. It is thus preferable to use scale end point data, which typically cannot have negative values. If end point data were not available, the reviewers used change data, but they were not subject to a meta‐analysis, and were reported in the 'Additional data' tables.

4.2.2 Summary statistic: for continuous outcomes a weighted mean difference (WMD) between groups was estimated. Again, if heterogeneity was found (see section 5) we used a random effects model.

4.2.3 Valid scales: we included continuous data from rating scales only if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal and the instrument was either a self report or completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist).

4.2.4 Endpoint versus change data: where possible we presented endpoint data. If both endpoint and change data were available for the same outcomes we reported only the former.

4.2.5 Cluster trials: studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997;Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra class correlation co‐efficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intra‐class correlation co‐efficient (ICC) Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC (Donner 2002).If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account intra‐class correlation co‐efficients and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would have been possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

5. Investigation for heterogeneity

Firstly, we considered all the included studies within any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity. Then we visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity. This was supplemented, primarily, by employing the I‐squared statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance. Where the I‐squared estimate was greater than or equal to 75%, this was interpreted as evidence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). Data were then re‐analysed using a random effects model to see if this made a substantial difference. If it did, and results became more consistent, i.e. falling below 75% in the estimate, the studies were added to the main body of trials. If using the random effects model did not make a difference and inconsistency remained high, data were not summated, but were presented separately and reasons for heterogeneity investigated.

6. Addressing publication bias We entered data from all included studies into a funnel graph (trial effect against trial size) in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias (Egger 1997).

7. Sensitivity analyses We analysed the effect of including studies with high attrition rates in a sensitivity analysis Where a trial was described as 'double‐blind' but implied that the study was randomised, it was also included in a sensitivity analysis.

8. General Where possible, we entered data in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for clotiapine.

Results

Description of studies

1. Excluded studies We excluded twenty eight studies. These were mostly uncontrolled clinical trials where outcomes in the same people were compared before and after the use of clotiapine. Block 1974 was a randomised controlled trial, but did not include any participants suffering from acute psychosis. Kammerer 1967 fitted all the inclusion criteria, being a randomised controlled trial comparing clotiapine to 'standard medication' for treatment of 'psychotic' or 'pre‐psychotic' people but not all participants were in an acute condition and it was impossible to extract data for these people alone. We therefore had to exclude this study. Rodova 1971 was randomised ‐ according to the scheme A‐B‐A‐B... ‐ using clotiapine versus perphenazine for people with schizophrenia, some of whom were acutely ill. We excluded this study because it was a cross‐over trial and data were not available for acutely ill people before the cross‐over. Kaneko 1969 compared clotiapine with chlorpromazine using matched pairs with treatment allocated by 'the double‐blind technique'; randomisation was not mentioned. Moreover, not all participants were acutely ill and it was impossible to ascertain exact numbers of those who were acutely ill from the data presented. Van Wyk 1971 fitted all inclusion criteria, but more than 50% of participants were discharged from hospital before the end of the trial, without follow up, so there was not any outcome data for these people. Reported information did not allow calculation of exactly how many participants were discharged and therefore did not address the issue of 'hospital and service outcome'. For this reason, we also excluded this study.

2. Awaiting assessment Two studies are currently awaiting assessment. One has proved unobtainable and the other requires translation.

Three more studies have been added to awaiting classification as a result of additional searching in 2012.

The total number of studies in awaiting assessment is now five.

3. Included studies We identified no new studies for inclusion in the update search of 2004.

3.1 Duration We included five trials, each lasting between six and sixty days. Only two studies, both of which lasted one week (Subramaney 1998; Uys 1996), measured outcomes at 24 hours or less, thus presenting some data regarding the speed of action of clotiapine. Other studies reported outcomes every few days or weekly (Itoh 1969).

3.2 Trial size The number of people in the included studies ranged from 30 to 80. We could not always use data from all participants as some did not fit the inclusion criteria. Due to this fact, we were only able to include four participants from the largest trial (Itoh 1969) and the total number of people randomised in relevant studies is currently only 185.

3.3 Participants All studies included people with schizophrenia. Jacobsson 1974 described how participants in their study suffered from 'psychotic syndromes of a schizophrenic type'. Perales 1974 included only people with 'paranoid schizophrenia'. In Subramaney 1998, people with 'organic' (substance induced) psychosis and bipolar disorder were also included. Uys 1996 also included those with bipolar disorder and people with 'acute paranoid reaction', 'other and unspecific reactive psychosis' and 'unspecific psychosis'. Every article contained the word 'acute' or 'acutely' in the description of the participants' condition, except Itoh 1969, which used the phrase 'in a state of intense excitement'. No definition of 'acute' was given. All trials were conducted on adults. Only Uys 1996 and Jacobsson 1974 gave their reasons for excluding participants from their studies.

3.4 Settings All trials were conducted on people of both sexes, except Uys 1996, whose participants were all men. All were hospital patients and it seems that no person over the age of 65 was included in any of the trials. We cannot be certain of this last fact as Itoh 1969 only reported the mean age and standard deviation of its participants.

3.5 Interventions 3.5.1 Experimental drug Clotiapine was given by intramuscular injection (40‐160 mg/day) in Subramaney 1998; Uys 1996 and during the five first days in Perales 1974, after which it was administered orally. This treatment routine was also used in Itoh 1969 and Jacobsson 1974, in daily doses ranging from 40‐290 mg.

3.5.2 Comparison drugs Itoh 1969 used perphenazine orally, between 12 mg and 64 mg/day. Jacobsson 1974 used oral chlorpromazine as the control treatment, with doses ranging from 100 mg to 600 mg/day. Perales 1974 compared trifluoperazine to clotiapine. The drug was given IM ‐ 2‐8 mg/day ‐ on days one to five and then orally ‐ 10‐40 mg/day ‐ on the remaining 40 days. Lorazepam IM, up to 16 mg/day, was compared to clotiapine in Subramaney 1998. Uys 1996 used zuclopenthixol acetate with participants receiving 150 mg of this drug every 72 hours.

In Itoh 1969; Jacobsson 1974 and Perales 1974, clotiapine was compared to 'standard drug treatment', whereas in Uys 1996 it was considered as 'standard' medication when compared to zuclopenthixol acetate. In Subramaney 1998 clotiapine and lorazepam were of equal preference.

3.6 Outcome measures For clinical outcomes, data were mostly continuous, presented as mean values commonly without standard deviations (SD). Uys 1996 presented data in graphical form only. All trials used some published rating scales (see below), but Subramaney 1998 was the only study to use exclusively published, validated rating scales. Other outcome measurements that were used included categorical scales measuring degrees of clinical improvement as defined by the study (Perales 1974). Jacobsson 1974 measured the number of people needing antiparkinsonian drugs, whereas Perales 1974 was interested in the quantity of such drugs used. Jacobsson 1974 addressed hospital and service outcomes by presenting the number of people substantially improved and discharged before the end of the trial.

3.6.1 Scales used 3.6.1.1 Behaviour Overt Aggression Scale ‐ OAS (Yudofsky 1986) This is a scale designed to measure the level of verbal and physical aggression. Sixteen items, all aggressive incidents, are classified according to the degree of aggressiveness implicated. Rating also depends on the duration of each incident as well as the intervention required to control it. High scores indicate a higher level of aggression.

3.6.1.2 Mental state Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) The BPRS is an 18‐item scale measuring positive symptoms, general psychopathology and affective symptoms. The original scale has sixteen items, but a revised eighteen‐item scale is commonly used. Scores can range from 0‐126. Each item is rated on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', with high scores indicating more severe symptoms.

3.6.1.3 Adverse effects Simpson‐Angus Scale ‐ SAS (Simpson 1970) The SAS is a 10‐item scale that is used to evaluate the presence and severity of drug‐induced parkinsonian symptomatology. The ten items focus on rigidity rather than bradykinesia (slow or retarded movement), and do not assess subjective rigidity or slowness. Items are rated for severity on a 0‐4 scale, with a scoring system of 0‐4 for each item. A low score indicates low levels of parkinsonism. 4. Missing outcomes Economic outcomes and satisfaction with care were not addressed in any of the trials.

5. Pharmaceutical industry support At least two studies (Itoh 1969; Uys 1996) were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company.

Risk of bias in included studies

1. Randomisation Itoh 1969 and Perales 1974 stated that random sequences were generated according to a table of random numbers, whereas Jacobsson 1974 used a pre‐established code, but did not explain the process of 'pre‐establishment'. The two remaining studies merely stated that treatment allocation was randomised but gave no further details on the procedure. We contacted the authors who informed us that randomisation had been generated by tossing coins. Concerning allocation concealment, Itoh 1969 used identical‐looking medication and coded bottles whereas, in Jacobsson 1974, the medication assignment was concealed in coded envelopes. It was not specified whether these envelopes were opaque or sealed. Uys 1996 and Perales 1974 did not conceal treatment assignment to the person responsible for administering the medication, only to the raters. Subramaney 1998 did not mention allocation concealment.

2. Blinding at outcome All reports specified blindness at outcome, but none tested the quality of this blinding.

3. Description of losses to follow‐up Perales 1974 had no people leaving the study early and included all participants in the analysis. In Itoh 1969, two people were not included in the presentation of results but there was no explanation for this. Jacobsson 1974 reported that five participants in the chlorpromazine group (19%) and six in the clotiapine group (26%) left the study early. Detailed reasons for their exclusion were given and they were included in the analysis when possible. One participant in each treatment group (3%) dropped out from Subramaney 1998 on the last day of the study. They were included in all the data analysis except the last rating using the Overt Aggression Scale. Uys 1996 actively excluded four participants from the clotiapine group for 'protocol violation'. These people were not included in the data analysis.

4. Data reporting Most results were continuous and presented as mean values or in some cases in graphical form (Jacobsson 1974, Uys 1996). Only one study (Subramaney 1998) presented standard deviations. Itoh 1969 reported the exact numbers of people experiencing each outcome. This was also the case for some of the results in Jacobsson 1974, Perales 1974 and Uys 1996. Perales 1974 compared some items of the BPRS, presenting results solely as inexact p‐values, and therefore rendering data of no further value for re‐analysis within this review.

Effects of interventions

Using our search strategy, we found 470 citations including those supplied by Novartis (clotiapine was produced by Sandoz Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis currently holds Sandoz records). Thirty‐five citations referred to trials using clotiapine. We found all but four of the trials on the list given to us by Novartis; the remaining citations came from Embase, Medline and PsycLIT. The use of Pascal revealed few citations, adding no data to our previous search. We are still unable to locate one article. In the remaining studies, most were open clinical trials, but we found 10 controlled clinical trials, eight of which specified they were randomised. We found no randomised trials comparing clotiapine with placebo. The update search of 2004 identified no further studies.

1. COMPARISON 1. CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS

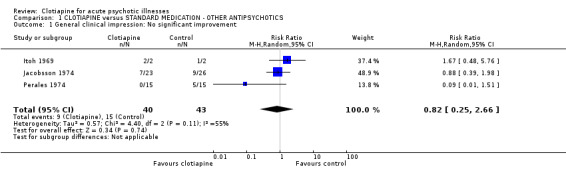

1.1 General improvement All older trials (Itoh 1969; Jacobsson 1974; Perales 1974) rated the degree of global improvement/deterioration, using clinicians' impressions. Pooled results were quite heterogeneous (I‐squared 58%), even when a random effects model was employed. We found that neither a single study nor the combined trials were in favour of clotiapine or the control drugs (n = 83, 3 RCTs, RR 0.82 CI 0.22 to 3.05).

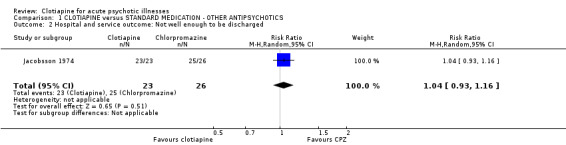

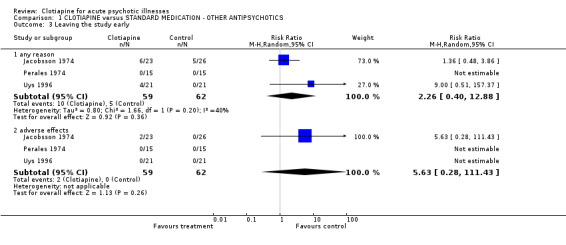

1.2 Hospital and service outcomes Only Jacobsson 1974 gave a detailed account of the number of people who left the study early because they felt significantly better ("cured"). The result was similar for clotiapine and chlorpromazine (n = 49, RR not well enough to be discharged 1.04 CI 0.96 to 1.12). 1.3 Leaving the study early Overall, there was no discernable difference in the numbers of people leaving the studies early from each group (n = 121, 17% vs. 8%, RR 2.3 CI 0.4 to 13). In Jacobsson 1974, two people were excluded from the trial because of severe adverse effects; one person left early as he was "cured" and the condition of eight people deteriorated and they had to be given alternative medication. In Uys 1996 four participants were excluded from data analysis for 'protocol violation'.

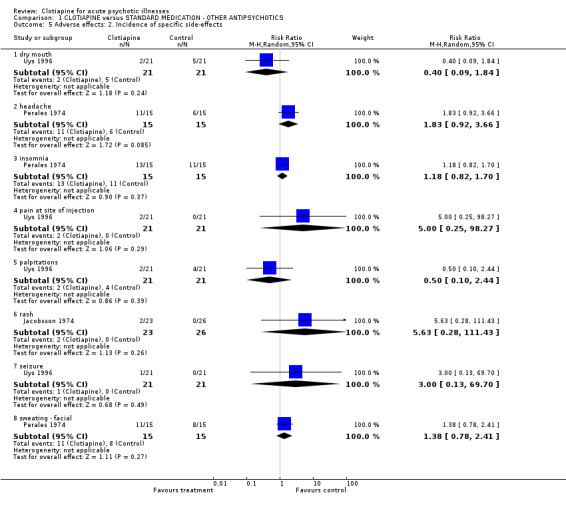

1.4 Adverse effects Itoh 1969 did not report any specific information on adverse effects.

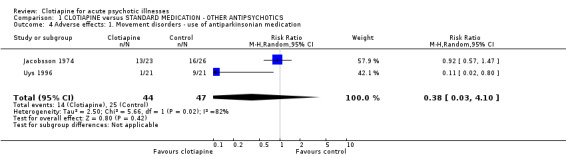

1.4.1 Movement disorders Jacobsson 1974 used their own scale for rating side effects and reported the use of antiparkinsonian drugs, finding no significant difference between clotiapine and chlorpromazine. Uys 1996 found that those allocated clotiapine had considerably less need of drugs than those given zuclopenthixol acetate, although the data were not statistically significant. The pooled results should be discounted because of significant heterogeneity (I‐squared 82%). Perales 1974 rated adverse effects according to Bordelau's Extrapyramidal Symptom Scale and quantity of antiparkinsonian treatment needed. These results favoured clotiapine, but the continuous data that were presented were useless for analysis as no variances around means were available.

1.4.2 Other adverse effects Jacobsson 1974 found both clotiapine and chlorpromazine caused significant initial tiredness and constipation, although this data was not reported. Two participants from the clotiapine group had to be excluded from the trial due to rashes. The most frequent adverse effects were noted; insomnia, headache and facial sweating, and they all appeared more often in those administered clotiapine. Uys 1996 employed the reduced UKU Side Effect Rating Scale and quantification of antiparkinsonian medication used. Both favoured clotiapine. These researchers also recorded pain at injection site which was only experienced by those in the clotiapine group.

1.5 Additional outcomes presented in the trials but with no useful data for analysis 1.5.1 Behaviour Jacobsson 1974 measured behaviour using the Wing rating scale for ward behaviour and concluded that both drugs produced a significant improvement in participants' behaviour and hence the effect of clotiapine could be compared to that of chlorpromazine. Data were presented in mean values with no standard deviation.

1.5.2 Sedation Uys 1996 assessed the level of sedation of participants on a Likert scale and found that with both treatments sedation appeared rapidly and peaked at eight hours. No data were presented to support this evidence.

1.5.3 Mental state Itoh 1969 used a rating scale and found clotiapine to be as effective as perphenazine in the treatment of schizophrenia. We were not able to extract data for the acute condition. Jacobsson 1974 rated the mental state of participants according to their specific modification of Martens & Jonsson's Symptom Scale and concluded that both drugs produced a significant reduction in the severity of symptoms, clotiapine being comparable to chlorpromazine. We could not report data as means were presented without the variance. Perales 1974 and Uys 1996 applied the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Perales 1974 concluded that clotiapine produced significantly more improvement than trifluoperazine with p<0.05 and no other data were presented to support this finding. Uys 1996, using the Bech Rafaelsen Mania Rating Scale to evaluate manic symptoms, found no significant difference between the two treatment groups, presenting results in mean values without variances.

1.6 Missing outcomes No study rated satisfaction with care or reported from an economic perspective.

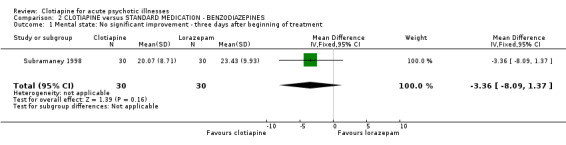

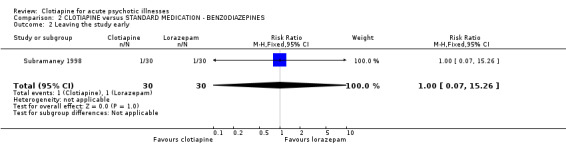

2. COMPARISON 2. CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ BENZODIAZEPINES Only Subramaney 1998 used a benzodiazepine lorazepam as the drug of comparison.

2.1 Mental state Mental state was measured according to the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Results were only slightly in favour of clotiapine (n = 60, MD ‐3.4 CI ‐8.1 to 1.4).

2.2 Leaving the study early One participant in each treatment group dropped out before the end of the trial (n = 60, RR 1.00 CI 0.07 to 15.26).

2.3 Behaviour The trialists applied the Overt Aggression Scale (OAS) to measure aggression levels in participants. Behaviour improved with both treatments, but there was no significant difference between the two groups. The results were skewed so they are presented in tables.

2.4 Adverse effects Subramaney 1998 used the Simpson‐Angus Scale finding significantly fewer side effects with lorazepam (p = 0.0007). Again data were skewed, so could not be included in statistical analysis, but were presented separately in tables.

3. Sensitivity analyses Only one trial (Jacobsson 1974) had an attrition rate over 25% in one of its treatment groups. As precise reasons were given for every participant leaving the study early, we chose not to do a sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

1. Few studies Acute psychosis is difficult to study and co‐operation from the study population is rare. This may be one of the reasons for the scarcity of controlled clinical trials using clotiapine solely for this indication. Few relevant studies have taken place since the mid 1970s, which probably correlates with its disappearance from the market in many countries around this time (USA, United Kingdom and France amongst others). Novartis states that the main reason for its disappearance was financial, as it was not economically feasible to market an off‐patent compound. More recently, despite some interest in its use for chronic treatment‐resistant schizophrenia (Lokshin 1998), clotiapine has mostly been associated with management of alcoholism and drug abuse. More studies are needed for proper analysis of clotiapines efficacy.

2. Methodological quality 2.1 Randomisation Selection bias can be minimised through good quality blinding at allocation. Improper allocation concealment can affect estimation of treatment effects (Chalmers 1983). Only Itoh 1969 and Perales 1974 reported adequate methods of random sequence generation. Allocation concealment was also well described in Itoh 1969, but was not mentioned in any other study. No trial included in this review would have rated highly with respect to the CONSORT statement (Moher 2001). 2.2 Blinding Rigorous blinding procedures are considered important to minimise performance and attrition bias in controlled trials (Jadad 1996). In psychopharmacological studies, it could be assumed that blinding is particularly important, as outcome measures may be subjectively‐rated items. If outcomes are more concrete, such as death, hospital discharge and leaving the study early, blinding may not be quite so important. An adequate blinding mechanism (identical‐looking medication) was described in Itoh 1969 and Jacobsson 1974. Such a description was absent in Subramaney 1998. Perales 1974 and Uys 1996 could not be considered double‐blind trials as the compared treatments differed (two tablets versus one tablet, no placebo injections to match the number of injections in both groups), and were administered by an un‐blinded nurse. Moreover, no trial tested the blindness (by asking participants and research personnel which drug they thought was being administered) although there has been evidence that physicians can, more often than would be allowed by chance, differentiate a new drug from the older one used as a control (Fisher 1993). This can affect estimated efficacy of the tested drugs. Indeed, in a meta‐analysis of 22 'double‐blind' studies, the effect sizes of older drugs were only one‐half to one‐quarter the size of those reported in earlier studies in which the old drugs were the only agent appraised (Greenberg 1992). This bias is difficult to eliminate since what is measured in a controlled trial is precisely the difference in efficacy and safety between several tested treatments, and this difference is often what allows participants or raters to guess which medication is being administered.

2.3 Description of losses to follow up Attrition rates were low in all studies which is a common factor in short trials conducted in hospital. The highest number of drop‐outs was in Jacobsson 1974. This was the only trial to mention drop‐outs apart from Uys 1996, who listed 'protocol violation' as a reason for leaving the study early.

2.4 Data reporting Overall, data reporting was poor. Results were most often presented in mean values with no SD, making it impossible to re‐analyse. Unlike the other studies, Subramaney 1998 did present variances with its results and Uys 1996 might have included this information if it been a fully published trial.

3. Publication bias The data included in this review were insufficient to enter into a funnel plot so we could not address the possibility of publication bias.

4. Generalisability of findings 4.1 Setting All trials were set in hospital. Many people suffering from acute psychosis do require hospital admission so the results are relevant to everyday practice. Nevertheless, it would be of interest to assess the use of clotiapine for acute psychosis on an outpatient basis, thereby preventing the need for hospitalisation.

4.2 Duration The difference in duration between trials ‐ six days to 60 days ‐ influences the outcomes measured. Rapid tranquillisation is the first outcome of interest when dealing with acute psychotic people and should be assessed by measuring change in behaviour less than 24 hours after onset of medication. Only the shorter studies (Subramaney 1998; Uys 1996) addressed this time period, but we could not use their data. The longer studies had the potential to address the outcome of antipsychotic effect (Itoh 1969; Jacobsson 1974; Perales 1974), but again, very few data are presented.

4.3 Participants We modified the Inclusion criteria in the protocol during the reviewing process to include people suffering from acute psychosis due to substance abuse. This change was made because we felt there was no reason to exclude this category of participants as, in an emergency situation, it is not always possible to distinguish between drug‐induced and functional psychosis ‐ and there is a substantial co‐morbidity ‐ so the same treatment is applicable in both cases. This modification allowed us to include Subramaney 1998.

Groups of participants differed among the various included trials. Itoh 1969 included only people with schizophrenia, Jacobsson 1974 included those suffering from 'psychotic syndromes of a schizophrenic type', Perales 1974 limited inclusion criteria to paranoid schizophrenia and Uys 1996 specifically excluded people with organic psychosis. Only two trials, Subramaney 1998; Uys 1996 mentioned which diagnostic criteria they used to include people in their trial (DSM‐III‐R in the former, ICD 9 in the latter). It seems reasonable to suppose, with a few exceptions, that participants in Itoh 1969; Jacobsson 1974 and Perales 1974 were all 'psychotic', as in our current definition of the concept. No clear definition of 'acute' was reported, although all trials used this concept. We are unsure as to the exact meaning of 'acute' in these trials, but again, think it reasonable to assume that such a pragmatic use of this term would not limit the applicability of the results.

4.4 Control drug A different control drug was used in each included trial, making results difficult to compare, although this is somewhat obviated by each of the antipsychotic controls being a phenothiazine (Itoh 1969 ‐ perphenazine, Jacobsson 1974 ‐ chlorpromazine, Perales 1974 ‐ trifluoperazine). In Uys 1996 (comparison drug ‐ zuclopenthixol acetate), clotiapine was not the experimental drug but the control. This could have reduced its measured effect if the blinding was not rigorous (Greenberg 1992).

4.5 Outcomes Among the seven groups of pre‐defined outcomes, only five were addressed. We found no information regarding important outcomes such as tranquillisation, injury to others, compulsory administration of treatment, measured acceptance of treatment, change in hospital status, economic outcomes and satisfaction with care. Except for measurements of global improvement/deterioration, outcomes were always assessed using published rating scales. Where scales were employed, however, no criteria for response were defined and degree of improvement was proportional to the change in number of points recorded on each scale. This does not necessarily reflect a satisfactory degree of improvement as would be defined by carers, patients or their families. Along with the poor reporting of data, the limited outcomes recorded greatly lessens not so much the applicability, but the value of this review.

5. COMPARISON 1. CLOTIAPINE versus OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS 5.1 General improvement Four studies addressed this outcome (Itoh 1969; Jacobsson 1974; Perales 1974; Uys 1996), but Uys 1996 did not report usable data. Data are quite heterogeneous (I‐squared 58%). Itoh 1969 and Jacobsson 1974 were administering drugs orally and used a low potency neuroleptic as a comparison, whereas Perales 1974 compared clotiapine IM to trifluoperazine IM ‐ a high‐potency neuroleptic. For this general outcome there is no trial‐based evidence that clotiapine is either better or worse than other drugs.

5.2 Hospital and service outcomes Only one small (n = 49) trial addressed the issue of hospital discharge due to substantial improvement (Jacobsson 1974). The results were equivocal but it is problematic to draw conclusions from such limited data. 5.3 Leaving the study early Few people left these studies early and clotiapine was no different to the other control drugs.

5.4 Adverse effects Again data are limited. Two studies reported on the use of antiparkinsonian medication to control neuroleptic‐induced movement disorders, and there was significant heterogeneity between their results. Jacobsson 1974 used approximately the same amount of anticholinergic drugs in both treatment groups. This was probably because clotiapine was being compared to chlorpromazine, a similar drug as regards propensity to cause parkinsonism, whereas when clotiapine was compared with zuclopenthixol (Uys 1996), the latter group needed anticholinergic drugs more frequently than their counterparts receiving clotiapine.

Overall, the number of people suffering adverse effects was very small so it is impossible to determine the side effect profile of clotiapine. If new trials were to be conducted, however, the incidences of rashes and seizures resulting from use of clotiapine would be of particular interest.

5.5 Additional outcomes presented in the trials but with no useful data for analysis 5.5.1 Behaviour No definitive conclusion can be drawn regarding clotiapines effectiveness in the management of behavioural problems. Data are poorly reported, although Jacobsson 1974 seemed to indicate that clotiapine has a positive effect on behaviour, comparable to that of chlorpromazine ‐ a low‐potency neuroleptic with strong sedative properties. Behaviour may have been evaluated in the general improvement ratings. If so, separate information should have been given regarding this very relevant outcome.

5.5.2 Sedation Surprisingly, only one study, Uys 1996, addressed this outcome, when in many cases sedation proves the only way to manage acutely psychotic people with severely disturbed behaviour. Unfortunately, the finding that clotiapine has rapid sedative properties equal to those of zuclopenthixol acetate, was not supported by data. If this study had been fully published it would have been of great interest.

5.5.3 Mental state There is little evidence to support the superiority (or inferiority) of clotiapine's psychotropic properties when compared to other compounds. Globally, clotiapine was shown to be as good as other 'standard' and 'non‐standard' treatments of acute psychosis. Perales 1974 found the drug superior to trifluoperazine but presented only inexact 'p' values. As presentation of results on psychopathological measurements was generally poor, most data could not be used. However, although mental state as an outcome is of interest in the very short‐term follow up of these studies, it is not usually as important as immediate tranquillisation or sedation.

5.6 Outcomes absent from these studies Satisfaction with care and economic outcomes were not reported. This may be because these have only recently been recognised as important outcomes.

6. COMPARISON 2. CLOTIAPINE versus BENZODIAZEPINES Only one small study (Subramaney 1998) used a benzodiazepine, lorazepam, as the drug of comparison. If clotiapine is still a drug of choice in the emergency situation, as it appears to be in some countries, further comparative trials are needed.

6.1 Mental state No substantial difference in improvement between clotiapine and lorazepam was reported, although the latter is not known for its antipsychotic properties. This is not particularly surprising, as all participants were also receiving haloperidol as baseline therapy, with clotiapine and lorazepam being administered only for aggressive/violent outbursts.

6.2 Leaving the study early Only one participant in each treatment group dropped out before the end of the trial. It is not possible to draw conclusions except that study attrition was appropriately low.

6.3 Behaviour Data from the use of the Overt Aggression Scale (OAS) were skewed and are therefore presented in tables. Behaviour improved with both treatments. It is possible that each drug is equally potent at quelling aggression, or is equally useless, and that other methods used together with time, settled the situation.

6.4 Adverse effects Subramaney 1998 found fewer movement disorder adverse effects with lorazepam. This is an important advantage for this drug. However, in the absence of good data on tranquillisation (such as time from administering to tranquillisation), the primary reason for drug use in this trial, it is difficult to know how to consider the adverse effect profile. Should clotiapine be more tranquilising than lorazepam then its ability to quell the dangerous situation may outweigh the problem of clotiapines association with movement disorders.

6.5 [Note: the three citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the results and conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

1. For people with psychotic illness The use of clotiapine in preference to other methods of managing acute psychotic illness is not supported by research. There is no evidence supporting claims made by open clinical trials that it has a faster onset of action and stronger sedative properties than other compounds. There is, however, no evidence refuting its efficacy. Clotiapine may cause fewer movement disorders than zuclopenthixol acetate but does cause more than lorazepam.

2. For clinicians Recommendations on the use of clotiapine for people suffering from acute psychosis, rather than other 'standard' or 'non‐standard' treatments, is to be viewed with caution. This review found only a few, poorly reported controlled trials. Wide confidence intervals on all findings preclude statistically significant findings. Taking clotiapine results in less need for anticholinergic medication for extrapyramidal side effects compared to 150 mg zuclopenthixol acetate IM. Orally, clotiapine seems to produce a degree of clinical improvement and quantity of movement disorders comparable to that of chlorpromazine. No trial addressed the major clinical issue of 'rapid tranquillisation'. Clinical practice is often based on clinicians' judgement in the light of their experience. Nevertheless, this judgement is sometimes not up‐to‐date, or is based on a few isolated cases and not on objective issues. We strongly recommend that clinicians who value the use of clotiapine for acutely psychotic people should consider undertaking a randomised controlled trial of this drug, including a large study population and focusing on outcomes such as tranquillisation, aggression, sedation and satisfaction with care.

3. For managers/policy makers People who include clotiapine in their protocols for the management of acute psychosis should be aware that they could be criticised for this choice and would have no good evidence to support their preference for this drug.

4. For funders There is a need for funders to sponsor well designed, conducted and reported controlled trials on clotiapine for the management of acute psychotic people.

Implications for research.

1. General As with all similar studies, public registration of a study before anyone is randomised would ensure that participants could be confident that people would know that the study had at least taken place. Unique study numbers would help researchers to identify single studies from multiple publications and reduce the risk of duplicating the reporting of data. Compliance with CONSORT (Moher 2001), both on the part of authors and editors, would help to clarify methodology and many outcomes.

Intention‐to‐treat analysis should be performed on all outcomes and all trial data should be made easily accessible. A minimal requirement should be that all data should, at least, be presented as numbers. In addition, continuous data should be presented with means, standard deviations (or standard errors) and the number of participants. Data from graphs, 'p' values of differences and statements of significant or non‐significant differences are of limited value. Unfortunately, in spite of the large numbers of participants randomised, we were unable to use most of the data in the trials included in this review due to the high drop‐out rates observed and poor data reporting. 2. Specific 2.1 More studies This review highlighted the need for good quality controlled trials to assess the efficacy of clotiapine for the management of acute psychosis, in particular addressing outcomes of major importance such as tranquillisation, aggression, sedation and satisfaction of carers. There should also be controlled trials undertaken in the community to assess the drug's efficacy and safety in preventing hospitalisation.

2.2 Protocol adherence Acutely psychotic people are a difficult study population. Nevertheless, adherence to a simple, pragmatic trial protocol will avoid many problems and there are examples of such studies (Huf 2002b; TREC 2003).

2.3 Randomisation To reassure readers that selection bias has been properly addressed, explicit description of treatment allocation must be reported. Trialists should not only use, but also describe an adequate method by which they generated a random sequence and the methods used to conceal treatment allocation until the beginning of the trial.

2.4 Blinding Blinding participants, carers, outcome evaluators and possibly sponsors to the treatment is important to eliminate performance and detection bias. Blinding should, when possible, not only be attempted but tested.

2.5 Withdrawals Authors should avoid withdrawing people from analysis after randomisation as a consequence of protocol non‐compliance. Researchers should perform an intention‐to‐treat analysis and describe from which group withdrawals came, in order to evaluate exclusion bias.

2.6 Setting The effectiveness of clotiapine in reducing acute psychotic symptomatology should be evaluated in the community as well as in a hospital setting.

2.7 Outcome measures Primary outcomes of interest for the measurement of a drug's efficacy in handling acute psychosis, such as tranquillisation, sedation, level of aggression and injury to others, should be assessed within minutes or hours after the administration of the studied medication. Indeed, a treatment cannot be recommended for this indication if it has no immediate or short term clinical effect. Thereafter, outcomes such as 'compulsory administration of treatment', 'mental state' and 'acceptance of treatment' are also of relevant interest to mentally ill people and their carers, as are economic outcomes and satisfaction with care.

2.8 Presentation of data Authors should present measures of association between intervention and outcome, for example, relative risks, odds‐ratios, risk or mean difference, and the raw numbers. Binary outcomes should be reported as well as, or in preference to, continuous results as they are easier to interpret. It is strongly recommended that authors report confidence intervals and statistical power for comparisons presented in the papers. If p‐values are used, the exact value should be reported.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 July 2012 | Amended | Update search of Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Trial Register (see Search methods for identification of studies), three studies added to awaiting classification. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2000 Review first published: Issue 1, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 24 June 2004 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Clive Adams, Drew Davey, Nicola Howson, Nancy Owens and Tessa Grant from the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group for all their assistance with this review.

We would also like to thank Dr Toshiaki Furukawa of The Evidence‐Based Psychiatry Centre, Department of Psychiatry, Nagoya City University Medical School, for his help with translation. With thanks also to Mr Werner Hoffmann of Novartis Pharma, Berne, Switzerland, who readily provided information for this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Previous searches

2. Electronic searching for the original version 2.1 The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CENTRAL, Issue 2, 2000) was searched May 2000, using the phrase: [clotiapine or clothiapine or entumin]

2.2 We searched The Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Register (updated May 2000) using the phrase: [clotiapine or clothiapine or clotiapina or etumine or entumine or entumin or etumina or etomine or "HF 2159" or "LW 2159"]

2.3 We searched EMBASE (1980‐2000, May 2000) using the phrase: [clotiapine or clothiapine or clotiapina or etumine or entumine or entumin or etumina or etomine or "HF 2159" or "LW 2159"]

2.4 We searched MEDLINE (1966‐2000, May 2000) using the phrase: [clotiapine or clothiapine or clotiapina or etumine or entumine or entumin or etumina or etomine or "HF 2159" or "LW 2159"]

2.5 We searched PASCAL (http://services.inist.fr/public/fre/conslt2.htm, 1973‐2000, May 2000) through the Internet using the phrase: [clotiapine or clothiapine or clotiapina or etumine or entumine or entumin or etumina or etomine or "HF 2159" or "LW 2159"]

2.6 We searched PsycLIT (1970‐2000, May 2000) using the phrase: [clotiapine or clothiapine or clotiapina or etumine or entumine or entumin or etumina or etomine or "HF 2159" or "LW 2159"]

3. Hand searching We searched reference lists of included and excluded studies for additional relevant studies.

4. Requests for additional data 4.1 We contacted the Medical Information Centre of NOVARTIS, the company who markets clotiapine, for published and unpublished data on the drug. They sent us a search they had done in their database in April 2000, using the term 'Entumin'.

4.2 We contacted authors of relevant studies to inquire about other sources of relevant information.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 General clinical impression: No significant improvement | 3 | 83 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.25, 2.66] |

| 2 Hospital and service outcome: Not well enough to be discharged | 1 | 49 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.04 [0.93, 1.16] |

| 3 Leaving the study early | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 any reason | 3 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.26 [0.40, 12.88] |

| 3.2 adverse effects | 3 | 121 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.63 [0.28, 111.43] |

| 4 Adverse effects: 1. Movement disorders ‐ use of antiparkinsonian medication | 2 | 91 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.03, 4.10] |

| 5 Adverse effects: 2. Incidence of specific side‐effects | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 dry mouth | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.4 [0.09, 1.84] |

| 5.2 headache | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.83 [0.92, 3.66] |

| 5.3 insomnia | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.82, 1.70] |

| 5.4 pain at site of injection | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.25, 98.27] |

| 5.5 palpitations | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.10, 2.44] |

| 5.6 rash | 1 | 49 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.63 [0.28, 111.43] |

| 5.7 seizure | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.70] |

| 5.8 sweating ‐ facial | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.78, 2.41] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 1 General clinical impression: No significant improvement.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 2 Hospital and service outcome: Not well enough to be discharged.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 3 Leaving the study early.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 4 Adverse effects: 1. Movement disorders ‐ use of antiparkinsonian medication.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ OTHER ANTIPSYCHOTICS, Outcome 5 Adverse effects: 2. Incidence of specific side‐effects.

Comparison 2. CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ BENZODIAZEPINES.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mental state: No significant improvement ‐ three days after beginning of treatment | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.36 [‐8.09, 1.37] |

| 2 Leaving the study early | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.26] |

| 3 Behaviour: Aggression (Overt Aggression Scale, skewed data, high=poor) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.1 on admission | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.2 by 24 hours | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.3 by 72 hours | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.4 by 1 week | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4 Adverse effects: Movement disorders (Simpson‐Angus Scale, skewed data, high=poor) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.1 by 24 hours | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.2 by 72 hours | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.3 by 1 week | Other data | No numeric data |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 1 Mental state: No significant improvement ‐ three days after beginning of treatment.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 2 Leaving the study early.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 3 Behaviour: Aggression (Overt Aggression Scale, skewed data, high=poor).

| Behaviour: Aggression (Overt Aggression Scale, skewed data, high=poor) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Clotiapine N | Clotiapine mean (SD) | Lorazepam N | Lorazepam Mean (SD) |

| on admission | ||||

| Subramaney 1998 | 30 | 6.43 (4.07) | 30 | 5.87 (3.27) |

| by 24 hours | ||||

| Subramaney 1998 | 30 | 1.33 (2.78) | 30 | 1.83 (3.14) |

| by 72 hours | ||||

| Subramaney 1998 | 30 | 1.30 (2.85) | 30 | 1.17 (2.15) |

| by 1 week | ||||

| Subramaney 1998 | 29 | 1.41(4.14) | 29 | 1.03 (2.26) |

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 CLOTIAPINE versus STANDARD MEDICATION ‐ BENZODIAZEPINES, Outcome 4 Adverse effects: Movement disorders (Simpson‐Angus Scale, skewed data, high=poor).

| Adverse effects: Movement disorders (Simpson‐Angus Scale, skewed data, high=poor) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Clotiapine N | Clotiapine mean (SD) | Lorazepam N | Lorazepam mean (SD) |

| by 24 hours | ||||

| Subramaney 1998 | 30 | 2.67 (2.43) | 30 | 1.2 (1.81) |

| by 72 hours | ||||

| Subramaney 1998 | 30 | 2.83 (2.15) | 30 | 1.67 (2.47) |

| by 1 week | ||||

| Subramaney 1998 | 30 | 2.07 (1.86) | 30 | 1.37 (2.22) |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Itoh 1969.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, matched pairs, table of random numbers. Blinding: double. Duration: 60 days (preceded by 1 week washout). | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia. History: 4 in 'state of intense excitement' ‐ possible to extract data on only these people. N = 80 (4 included). Sex: 62 M, 18 F. Age: mean ˜34 years. Setting: hospital. Exclusion criteria: not mentioned. | |

| Interventions | 1. Clotiapine: dose 45 to 90 mg/day orally by day 7, as needed thereafter, range 90‐290 mg/day. N = 2. 2. Perphenazine: dose 12‐24 mg/day orally by day 7, as needed thereafter, range 24‐64 mg/day. N = 2. Antiparkinsonian drugs and hypnotics permitted. No mention of non‐pharmacological interventions. | |

| Outcomes | General improvement: overall clinical response.Unable to use ‐ Mental state: (BPRS ‐ data not extractable for 'acute' participants only). Adverse effects: (data not extractable for 'acute' participants only). Leaving the study early: (data not extractable for 'acute' participants only). | |

| Notes | Trial sponsored by drug company. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Jacobsson 1974.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, pre‐established code. Blinding: double. Duration: one month (preceded by 'a few days' washout). | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Diagnosis: 'psychotic syndromes of a schizophrenic type'. History: acute, first episode or relapse. N = 49. Sex: 23 M, 26 F. Age: range 18‐60 years. Setting: hospital. Exclusion criteria: neurological or somatic disorders, substance misuse as principal reason for hospital admission; history of spontaneous remission shortly after admission. | |

| Interventions | 1. Clotiapine: dose 40‐240 mg/day orally. N = 23. 2. Chlorpromazine: dose 100‐600 mg/day orally. N =2 6. Antiparkinsonian drugs and hypnotics permitted. No mention of non‐pharmacological interventions. | |

| Outcomes | General improvement: overall clinical response. Adverse effects: needing antiparkinsonian treatment. Leaving study early.Unable to use ‐ Behaviour: (Wing Rating Scale for Ward Behaviour ‐ no SD, inexact p values). Mental state: (Authors' modification of the 'Martens & Jonsson' Symptom Scale ‐ no SD, inexact p values). Adverse effects: (Scale for Rating of Side‐Effects ‐ no SD, inexact p values). | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Perales 1974.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised, table of random numbers. Blinding: double (but likely that oral doses of drugs caused unblinding). Duration: 45 days. | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Diagnosis: paranoid schizophrenia. History: acute. N = 30. Sex: 26 M, 4 F. Age: range 19‐43 years. Setting: hospital. Exclusion criteria: other psychiatric diagnosis. | |

| Interventions | 1. Clotiapine: dose 40‐160 mg/day IM from day 1‐5, then 40‐160 mg/day orally until the end of trial. N =1 5. 2. Trifluoperazine: dose 2‐8 mg/day IM from day one to day five, then 10‐40 mg/day orally until the end of trial. N = 15. Antiparkinsonian drugs were permitted. No mention of non‐pharmacological interventions. | |

| Outcomes | Global improvement: (degree of improvement on categorical scale). Adverse effects: (list of adverse effects). Leaving study early.Unable to use ‐ Mental state: (BPRS ‐ no SD, inexact p values). Adverse effects: (Bordelau's Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale, use of antiparkinsonian drugs ‐ no SD). | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Subramaney 1998.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised ‐ by toss of a coin. Blinding: double. Duration: one week. | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Diagnosis: organic (psycho‐active substance) hallucinations, organic delusional disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (DSM III). History: acutely behaviourally disturbed with aggressive, disorganised behaviour. N = 60. Sex: 46 M, 14 F. Age: range 18‐45 years. Setting: hospital. Exclusion criteria: physical illness, pregnancy, abnormal routine blood tests. | |

| Interventions | 1. Clotiapine: maximum dose 40 mg IM 6 hourly + haloperidol 10 mg/day orally. N = 30. 2. Lorazepam: maximum dose 4 mg IM 6 hourly + haloperidol 10 mg/day orally. N = 30. No mention of antiparkinsonian drugs or non‐pharmacological interventions. | |

| Outcomes | Mental state: (BPRS). Leaving study early.Unable to use ‐ Behaviour: Overt Aggression Scale (skewed data presented). Adverse effects: Simpson‐Angus Scale (skewed data presented). | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Uys 1996.

| Methods | Allocation: randomised ‐ by toss of a coin. Blinding: double. Duration: one week. | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Diagnosis: schizophrenia, acute paranoid reaction, other and unspecific reactive psychosis, unspecified psychosis, bipolar mood disorder‐manic phase (ICD 9). History: acute restless or aggresive behaviour. N = 42. Sex: 42 M. Age: range 18‐65 years. Setting: hospital. Exclusion criteria: oral neuroleptics within the last six hours or depot neuroleptics within the last two weeks, clinically relevant medical or neurological disease, known organic brain disorder, pregnancy or inadequate contraception, abnormal laboratory values or history of drug abuse. | |

| Interventions | 1. Clotiapine: dose 40 mg IM initially, then 80‐160 mg/day, in divided doses, orally or IM. N = 21. 2. Zuclopenthixol acetate: dose 150 mg IM initially, repeated once after 72 hours. N = 21. Antiparkinsonian drugs, lithium and benzodiazepines permitted. No mention of non‐pharmacological interventions. | |

| Outcomes | Adverse effects: (needing anticholinergic medication, frequent side‐effects, pain at site of injection). Leaving the study early.Unable to use ‐ General improvement: (CGI ‐ no data). Sedation: (Likert Scale ‐ no data). Mental state: (BPRS, Bech Rafaelsen Mania Rating Scale ‐ no SD). Adverse effects: (UKU ‐no usable data). | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bellomo 1973 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Bellomo 1975 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Bente 1966 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Block 1974 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: chronic alcoholics, suffering from 'anxiety, tension, irritability or depression', but 'not blunted so severely that they could not be expected to cooperate'. Clearly not acute psychosis. |

| Caldas 1971 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Cante 1971 | Allocation: not described. Participants: people with schizophrenia. Interventions: each group given same drug (clotiapine HF 2159). |

| Carra 1974 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Delay 1965 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Etienne 1976 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Gazzaniga 1972 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Gehring 1972 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Giordano 1973 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Kammerer 1967 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: 'psychotic' or 'prepsychotic' inpatients suffering from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder mostly melancholia, brief psychotic episodes, chronic delirium, 'prepsychotic states', depression associated with alcohol misuse. Not all participants were 'acutely' ill. Interventions: clotiapine versus 'standard medication'. Outcomes: impossible to extract data for relevant participants ‐ authors could not be located. |

| Kaneko 1969 | Allocation: by 'the double‐blind technique', matched pairs according to sex, age and clinical condition ‐ no mention of randomisation. Participants: people suffering from schizophrenia, some in a 'severe excited state' but could not be certain how many participants were in this condition, so data was not extractable for only these people. |

| Martin 1968 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Martins 1969 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Matsushita 1968 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Ohkuma 1970 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Oules 1973 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Rapidis 1975 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Rodova 1971 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia, most not in an 'acute' phase. Interventions: clotiapine versus perphenazine. Outcomes: no usable data; authors contacted and Professor Svestka kindly replied; initial randomisation confirmed but data not available for just acutely ill people before the first crossover. |

| Rosier 1974 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Savoldi 1967 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Toerien 1973 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Traldi 1969 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Van Wyk 1971 | Allocation: randomised. Participants: people with schizophrenia or 'toxic' psychosis (alcohol or drug abuse), acutely ill. Interventions: clotiapine versus chlorpromazine or thioridazine. Outcomes: attrition rate over 50%, no data on these participants and impossible to find out the exact number of dropouts; precise percentage of people cured and discharged from hospital before the end of the trial in each study group was presented. For two groups, these exact percentages amount to fractional numbers when applied to the number of participants in each group. We therefore supposed some data might be missing or have been modified. |

| Watanabe 1969 | Allocation: not randomised. |

| Zapletalek 1971 | Allocation: not randomised. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Ayuso‐Gutierrez 1973.

| Methods | |

|---|---|

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Belmaker 2009.

| Methods | |

|---|---|

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Geller 2005.

| Methods | |

|---|---|

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Notes | To be assessed. |

Nahunek 1981.