Role of SeqA and Dam in Escherichia coli gene expression: A global/microarray analysis (original) (raw)

Abstract

High-density oligonucleotide arrays were used to monitor global transcription patterns in Escherichia coli with various levels of Dam and SeqA proteins. Cells lacking Dam methyltransferase showed a modest increase in transcription of the genes belonging to the SOS regulon. Bacteria devoid of the SeqA protein, which preferentially binds hemimethylated DNA, were found to have a transcriptional profile almost identical to WT bacteria overexpressing Dam methyltransferase. The latter two strains differed from WT in two ways. First, the origin proximal genes were transcribed with increased frequency due to increased gene dosage. Second, chromosomal domains of high transcriptional activity alternate with regions of low activity, and our results indicate that the activity in each domain is modulated in the same way by SeqA deficiency or Dam overproduction. We suggest that the methylation status of the cell is an important factor in forming and/or maintaining chromosome structure.

The Escherichia coli dam gene encodes a DNA adenine methyltransferase that recognizes GATC sequences in double-stranded DNA and methylates the adenine residue at the N6 position (1). Methylation is a postreplicative process, and the time lag between replication and remethylation of the majority of GATCs has been estimated to be a few seconds for those in plasmids (2) and a few minutes for those on the chromosome (3). Newly replicated DNA is therefore methylated on one strand only; that is, it is hemimethylated and distinct from the rest of the chromosomal DNA.

The hemimethylated status of newly synthesized DNA provides a time window during which cellular processes such as repair of mismatched bases (4), regulation of gene expression (4), and suppression of initiation of chromosome replication (5) are activated or suppressed, thus linking these processes to the cell cycle (6).

The E. coli minimal origin of replication (oriC) contains 11 GATC sequences (7). After initiation of replication, the hemimethylated origin is inert to further initiation for a period of ≈30 min, or ≈1/3 doubling time (8). This eclipse period depends on the presence of the SeqA protein (9) and its length determined by the level of Dam methyltransferase (8). Lack of SeqA protein or overproduction of Dam methyltransferase leads to reinitiation at the same origin more than once per cell cycle, yielding a higher-than-normal origin concentration (10, 11).

The SeqA protein requires at least two hemimethylated GATC sites on the same face of DNA, separated by no more than one to three turns of the helix, for high-affinity binding (12). Fully methylated DNA is also bound but much less efficiently (12, 13). High-affinity sequences occur not only in oriC but also in hemimethylated DNA trailing replication forks, suggesting that SeqA may act as a nucleoid organizing protein (8, 12, 14, 15). Such a role is consistent with the observation that, in the absence of SeqA, the overall supercoiling of DNA increases and the nucleoid condenses (16). Proteins involved in establishing and maintaining chromosome structure also frequently affect the expression of numerous genes (global regulators). These include proteins H-NS, Fis, IHF, HU, etc. (17), but a similar connection has never been postulated for the SeqA protein.

We have applied high-density oligonucleotide arrays to analyze global gene expression in WT cells and in cells containing various levels of Dam and SeqA proteins. The results are discussed in relation to gene dosage and DNA structure.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains.

All strains are derived from E. coli K-12 MG1655 (18) and are as follows: KS9921(Δ_seqA_); ALO1738 (_dam13_∷Tn9); ALO1739(aroK17_∷_cat/pMS2); ALO1740(pTP166); ALO1832(pMAK7); and ALO1834(pFH539). Plasmids pMS2 (aroK, aroB; ref. 19), pTP166 (pTAC-dam; ref. 20), pMAK7 (pTAC-seqA; ref. 8), and pFHC539 (dnaA; ref. 21) have been described.

Media.

Cells were grown in AB minimal medium (22) supplemented with 1 μg/ml thiamine/0.2% glucose/0.5% casamino acids. When necessary, ampicillin and tetracycline were added to media at final concentrations of 100 and 10 μg/ml, respectively.

Data Collection and Analysis.

RNA was isolated from cells and processed as described (23). Affymetrix E. coli (MG1655) chips were hybridized with equal amounts of fluorescence-labeled RNA from the E. coli MG1655 derivatives, scanned exactly as described in the Affymetrix User Guide (www.affymetrix.com), and analyzed by using genechip analysis suite software. Raw data were exported as text files and imported into Microsoft excel (OFFICE 2000), in which further sorting was accomplished. We compared the 4,242 genes encoding proteins but not intergenic regions or RNA genes. In the comparison, we required that the actual numbers be above a (more or less arbitrarily chosen) threshold of 400 scanning units. Using this value, we typically obtained “present calls” for between 3,200 and 4,000 genes. The average expression for all genes (including those with an absence call or negative value) was 4,600 scanning units, and the highest expressed genes (encoding components of the protein synthesis apparatus) were ≈50,000–65,000 scanning units. Trendlines were obtained as fifth-order polynomials from Microsoft excel.

For the comparison analyses shown in Tables 1–3, we required that the gene expression in one of the strains of the comparison exceed 2,000 scanning units, and that the difference in expression level be 2-fold or more. Genes with unknown functions were not included.

Table 1.

Internal controls for gene expression data

| Gene | Probe set | seqA/wt | p_seqA_/wt | dam/wt | p_dam_/wt | aroK_∷_cat/wt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seqA | b0687 | 0.06* | 48 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.66 |

| pgm | b0688 | 0.36 | 1.3 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.76 |

| aroK | b3390 | 1.1 | 0.90 | 1.1 | 0.94 | 2.4† |

| aroB | b3389 | 1.1 | 0.98 | 1.1 | 0.87 | 4.6† |

| damX | b3388 | 1.1 | 0.83 | 1.0 | 0.99 | 0.53 |

| dam | b3387 | 1.1 | 0.93 | 0.37 | 10 | 0.51 |

| rpe | b3386 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.32 | 0.89 | 0.42 |

| gph | b3385 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.43 | 0.81 | 0.46 |

| trpS | b3384 | 0.99 | 1.3 | 0.42 | 0.92 | 0.38 |

Table 3.

Genes with a 2-fold change in expression in either the seqA mutant or a strain overproducing Dam compared to MG1655

| Gene | Probe set | seqA/wt | p_dam_/wt | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | Corrected | Raw | Corrected | ||

| cydC* | b0886 | 0.13A | 0.19 | 0.61 | 0.68 |

| gapC | b1417 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.44 |

| rmf* | b0953 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.34 |

| gltD | b3213 | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.46 |

| rpsV | b1480 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| gltB | b3212 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.44 |

| thrB* | b0003 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.44 |

| cirA | b2155 | 0.32 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.43 |

| trpD | b1263 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.52 |

| trpE | b1264 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.59 |

| cspI* | b1552 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.49 |

| dps* | b0812 | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.37 |

| amn | b1982 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.52 |

| hdeB* | b3509 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.32 |

| uraA* | b2497 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.76 | 0.76 |

| ddg* | b2378 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.54 |

| dld* | b2133 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.63 | 0.67 |

| hdeA* | b3510 | 0.65 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.31 |

| trpC | b1262 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.49 |

| tpr* | b1229 | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.48 |

| osmC | b1482 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.43 |

| osmE* | b1739 | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.49 |

| osmY | b4376 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.36 |

| elaB* | b2266 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

| hisI | b2026 | 0.53† | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.42 |

| wbbI* | b2034 | 0.56 | 0.72 | 0.41 | 0.45 |

| sgbH* | b3581 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 2.1 |

| ascF* | b2715 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| recN* | b2616 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| ilvN* | b3670 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| malK | b4035 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| cysU* | b2424 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| stpA | b2669 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| proA | b0243 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.4 |

| lamB | b4036 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| malE | b4034 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| cysA | b2422 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| hcaC* | b2540 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| cysD* | b2752 | 2.5† | 2.4 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| oraA* | b2698 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| cysP* | b2425 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| dinI* | b1061 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| sulA | b0958 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

| umuD | b1183 | 2.7 | 4.0 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| intE* | b1140 | 2.9† | 4.3 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| cysN* | b2751 | 6.7‡ | 6.5 | 6.3‡ | 6.0 |

| gltS* | b3653 | 9.3‡ | 6.8 | 6.8‡ | 5.6 |

All data from the microarray analysis can be found at http://users.umassmed.edu/martin.marinus/arrays.

Results

Internal Controls for Gene Expression Data.

To identify genes that are regulated positively or negatively by dam methylation or by SeqA, we measured global gene transcription in the WT strain MG1655 and various derivatives of it, including strains with null mutations (dam-13_∷Tn_9, seqA), an aroK17_∷_cat derivative with only 30% the level of Dam methyltransferase relative to WT (24), and Dam and SeqA plasmid overproducers.

Global gene transcription in different bacterial strains was analyzed by using Affymetrix high-density oligonucleotide arrays (23). Three separate data sets were collected in two different laboratories [University of Massachusetts Medical School (Worcester, MA) and Technical University of Denmark (Copenhagen)]. As internal controls, we found that there was reduced transcription (due to polar effects) of genes downstream of the insertion/deletion mutations in dam or seqA operons and increased transcription of dam and seqA in overproducing strains (Table 1). These data are consistent with the expected results of each strain analyzed and show that the data sets obtained from the genome arrays are reliable and can be used to quantify transcription of individual genes within the cell.

Gene Expression in the Absence of dam Methylation.

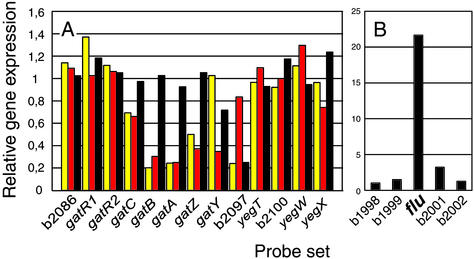

Transcription of only a few genes was reduced >2-fold in the absence of Dam methylation (Table 2). The dnaA gene showed a moderate decrease, confirming previous data that dnaA transcription is reduced in the eclipse period (25) and in the absence of methylation (26). The expression of the entire gat (galactitol) operon was also reduced (Fig. 1A). Genes that were significantly increased in the absence of methylation were also infrequent, and the increase in most cases was modest (Table 2). The majority of these genes were part of the SOS regulon, e.g., recA, oraA (recX regulatory protein), recN, sulA, dinI, and umuDC. This is in agreement with previous observations that dam cells have a higher basal level of SOS gene expression (27).

Table 2.

Gene expression in Dam-deficient cells

| Gene | Probe set | Relative expression | lacZ |

|---|---|---|---|

| sulA | b0958 | 1.8 (2.1) | 5.9 (ref. 27) |

| glnS | b0680 | 1.9 (3.0) | 2.7 (ref. 41) |

| lexA* | b4043 | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.7 (ref. 27) |

| oraA | b2698 | 1.8 (3.0) | |

| recA | b2699 | 1.3 (2.8) | 3.0 (ref. 27) |

| uvrA* | b4058 | 1.3 (2.3) | 2.2 (ref. 27) |

| uvrB* | b0779 | 1.0 (1.3) | 2.3 (ref. 27) |

| dinF* | b4044 | 1.2 (0.9) | 3.3 (ref. 27) |

| trpR* | b4393 | 1.2 | 2.3 (ref. 42) |

| dinI | b1061 | 2.0 | |

| proA | b0243 | 2.6 | |

| marR | b1530 | 0.4 | |

| rbsD | b3748 | 0.4 | |

| csgG | b1037 | 0.4 | |

| dld | b2133 | 0.5 | |

| mtlA | b3599 | 0.5 | |

| dnaA* | b3702 | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.25–0.5 (ref. 26) |

Figure 1.

Gene expression of the gat operon and the flu gene. (A) Gene expression data from the gat operon region are comparisons between MG1655 seqA (yellow), MG1655 dam-13_∷Tn_9 (red), or MG1655 carrying plasmid pTP166 (Dam overproducer, black) and WT MG1655. The genes are listed in order of location on the chromosome, from b2086 to yegX. (B) Gene expression data for the flu and neighboring genes in MG1655 containing plasmid pTP166 compared with WT. Gene expression data were corrected for gene dosage as described in the legend to Table 3.

Table 2 also lists lacZ transcriptional fusion data previously compiled for genes showing altered expression in the absence of dam methylation. Genes with increased expression in lacZ fusion analyses also had increased expression in our array analysis, albeit to a lesser extent.

We conclude that few genes were subject to either decreased or increased expression in the absence of Dam methylation. The majority of genes that showed an increase in expression belonged to the SOS regulon (28). A number of genes including carAB, pspA, rspA, and proP containing GATC sequences in their promoter regions (29) did not show altered expression in dam mutant cells.

Hemimethylation Has Little Effect on Gene Expression.

Transient turn-on or shut-off of genes by hemimethylation is frequently suggested as a way of coupling gene expression to cell cycle progression, i.e., by the passage of a replication fork (30). We therefore constructed a strain with an altered duration of hemimethylation by introducing the aroK17_∷_cat mutation into strain MG1655. Global gene expression in the aroK17∷cat mutant was indistinguishable from WT, except for distal genes in the dam operon (Table 1). These were reduced due to the polar effects of the aroK17∷cat mutation that terminates transcription from the dam P1 and P2 promoters (19, 24). These data argue that no genes in the cell are specifically induced by hemimethylation.

A 10-fold increase in dam transcription from plasmid pTP166 (Table 1), however, led to an altered expression pattern of numerous genes, most of which were also regulated by the SeqA protein (see below). Among the genes independent of SeqA action was flu, encoding antigen 43, for which we observed an almost 20-fold increase in expression at high Dam expression (Fig. 1B).

Genes Regulated by the SeqA Protein.

To determine whether there was an overlap in genes regulated by methylation or SeqA protein, we analyzed global gene expression in the seqA mutant. There was little overlap between the dam and seqA mutant transcriptional profiles (compare Tables 2 and 3). Expression of the gat operon depended on methylation as well as on the SeqA protein (Fig. 1A). Transcription of the umuDC, sulA, and dinI genes, belonging to the SOS regulon, was also increased in both strains, suggesting that seqA deficiency also leads to SOS induction (9).

SeqA mutants and cells overexpressing the Dam protein had remarkably similar gene expression patterns. Genes showing increased or decreased expression in _seqA-_deficient cells did the same in Dam-overproducing cells (Table 3). That is, overproduction of Dam methyltransferase in the WT interferes with the normal action of SeqA. Because both these proteins have a high affinity for hemimethylated DNA and because Dam acts at the replication fork, its interference of SeqA action implies that SeqA also acts on hemimethylated DNA at the replication fork. We note that genes regulated by SeqA deficiency or Dam overproduction share no common features such as GATC motifs (Table 3) in their promoter sequences, other than those involved in interaction with RNA polymerase, excluding the possibility that SeqA acts directly at promoter sequences to modulate transcription.

We conclude that deletion of the seqA gene or Dam overproduction leads to the same effects on global gene expression but was clearly different from Dam deficiency.

Overinitiation in SeqA-Deficient and Dam-Overproducing Cells.

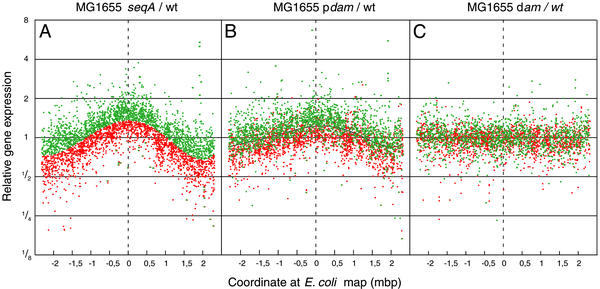

When we analyzed gene expression data for seqA deleted cells, we noticed subtle changes for a large number of genes relative to WT. We therefore plotted the relative expression values of all genes, relative to their position on the chromosome (Fig. 2A). It appears that the amount of mRNA from genes centered around the origin of replication (position 0 on the abscissa) was increased relative to WT. Similarly, the amount of mRNA from genes located close to the terminus of the chromosome was decreased. A similar gene expression pattern was observed for cells overproducing the Dam methyltransferase (Fig. 2B), although the relative differences were slightly less. For dam mutant cells (Fig. 2C), we could not detect any position-dependent variation relative to WT cells. Excessive initiation events at oriC have previously been observed in both seqA mutant cells (9, 10) and Dam-overproducing cells (31), leading to an increased origin/terminus ratio. It is likely that the altered pattern in mRNA abundance in seqA mutants and Dam overproducers reflects gene dosage, which in turn indicates that the majority of genes are expressed in proportion to their gene dosage.

Figure 2.

Expression of individual genes as a function of position on the chromosome. All genes for which a “present” call was obtained were plotted relative to WT as a function of position along the chromosome. The chromosome is linearized at a position directly opposite oriC. The replication origin has position 0 on the abscissa. (A) MG1655 seqA. (B) MG1655/pTP166 (Dam overproducer). (C) MG1655 dam-13_∷Tn_9. Trendlines for the gene expression data are presented in A and B. All points above the trendline in A, i.e., genes that were derepressed in the seqA mutant are plotted as green dots, and all genes that were repressed in the seqA mutant as red dots. Expression data from individual genes in B and C have the same color assignment as in A (red and green dots).

The lowest relative mRNA abundance was found in an area of the chromosome corresponding to a position 2 Mb from the origin (27 min on the genetic map), which is not directly opposite oriC. This suggests that in the seqA mutant and Dam overproducer, the rightward replication fork travels a shorter distance than the leftward and terminates in a region not diametrically opposite to oriC but close to the terA and terD sites. A similar asymmetry of termination has previously been observed in a dnaC(Ts) strain (32). The reason for the shorter migration for the rightward replication fork may be that it is slowed by five encounters with highly transcribed rRNA operons relative to the leftward fork that encounters only two rRNA operons (33).

In addition to gene-dosage-dependent changes, differences in expression of individual genes also exist between seqA and Dam overproducer cells and WT. To determine whether these changes were similar for seqA and Dam overproducer cells, we identified genes that were derepressed in the seqA mutant cells after correction for gene position, i.e., above the trendline. These genes are indicated by the green dots in Fig. 2A. Genes that were repressed relative to WT are indicated by the red dots. When the same color assignment was maintained for individual genes of the Dam overproducer cells (Fig. 2B), it was clear that the same genes, by and large, were derepressed and repressed in the two strains. In the dam mutant cells, no obvious pattern was observed in the two classes of genes (Fig. 2C).

We conclude that the absence of SeqA protein and high DNA methyltransferase levels affect global gene expression in a similar way, but that a different pattern is found in a dam mutant.

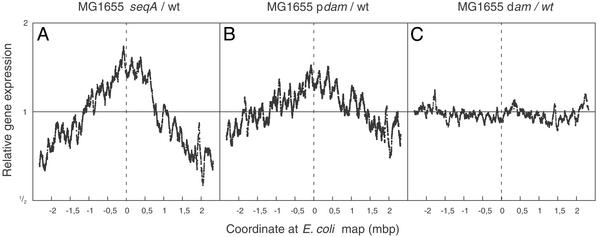

Transcription Domains in the E. coli Chromosome.

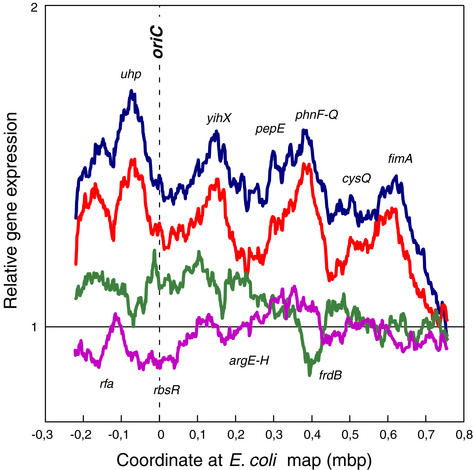

To define methylation-dependent domains in the chromosome, we plotted the relative expression level of a moving window of 50 adjacent genes as a function of their position on the chromosome (Fig. 3). In addition to the gene dosage effect of seqA deficiency or Dam overproduction, a detailed pattern of altered local gene expression was discernable. A high degree of fluctuation with distinct peaks and troughs was apparent (Fig. 3 A and B). The overall pattern was completely different from the dam mutant (Fig. 3C). The similarity between the transcription profiles of seqA and Dam-overproducing cells extended through the entire chromosome but was most obvious around the origin of replication (Fig. 4). Furthermore, it was not the result of overinitiation per se, because overproduction of DnaA protein, which also led to increased initiation at oriC, did not give the same pattern of peaks and troughs (Fig. 4). The pattern did not correlate with the occurrence of GATC sites, single or in clusters of two, three, or four along the chromosome (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Chromosomal domains. A moving window representing the average expression of 50 expressed genes (data from Fig. 2) is plotted as a function of gene position on the chromosome and relative to WT. The chromosome is linearized at a position directly opposite oriC. The replication origin has position 0 on the abscissa. (A) MG1655 seqA. (B) MG1655/pTP166 (Dam overproducer). (C) MG1655 dam-13_∷Tn_9. The flu gene and the plasmid-encoded dam gene were omitted from the analysis of the Dam overproducing strain presented in B.

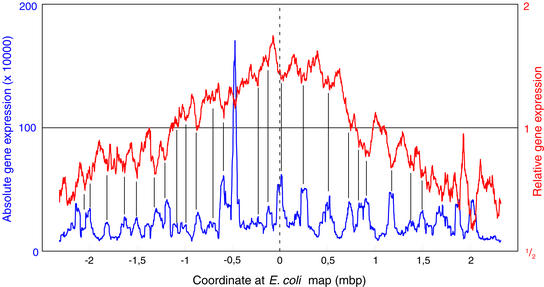

Figure 4.

Expression domains in the vicinity of oriC. A moving window representing the average expression of 50 expressed genes is plotted as a function of gene position on the chromosome and relative to WT. Blue, MG1655 seqA; orange, MG1655/pTP166 (Dam overproducer), red-violet, MG1655 dam-13_∷Tn_9; green, MG1655/pFHC539 (DnaA overproducer). Blue, orange, and red-violet curves are replotted from Fig. 3.

In Fig. 5, we correlate the changes in gene expression of seqA mutant cells relative to WT cells (red line) to the absolute transcriptional level in different regions of the chromosome of WT cells (blue line). It should be emphasized that the absolute expression profiles are very similar for the WT, the _seqA-_deficient, and the Dam-overproducing strains (data not shown). However, in every case, the peaks for regions with high transcriptional activity correlate with troughs in the seqA/WT (and the Dam overproducer/WT) profile and vice versa. This indicates that, on average, genes that are highly expressed in WT show decreased expression in seqA mutant cells (10–30% as an average of the 50 genes in the window), whereas genes with low expression in WT show increased expression in seqA cells.

Figure 5.

Peaks and troughs observed in the comparison of MG1655 seqA with WT are inversely correlated with the transcriptional intensity in regions of the MG1655 (WT) chromosome. The red curve represents the seqA/WT comparison from Fig. 3A. The blue curve is a moving window of the primary gene expression values of 50 genes (scanning units) on the MG1655 chromosome.

We conclude that SeqA deficiency and Dam overproduction lead to the same changes in gene expression in localized regions of the chromosome. These changes are not present in dam mutant cells and did not result from overinitiation of chromosome replication. Rather, they were correlated with the total transcriptional activity in the region.

Discussion

In the absence of Dam methylation, few genes displayed altered expression and the majority of these belonged to the SOS regulon. The basis for increased SOS regulon expression is an active MutHLS repair system that can make incisions on either strand of the DNA anywhere on the chromosome, producing single-strand nicks or gaps that can lead to the formation of double-strand breaks (34).

The oriC-dnaA region of the chromosome remains hemimethylated for extended periods of time (35), and in the aroK17_∷_cat mutant these are expected to be hemimethylated for most of the cell cycle. Some of the genes in this regions, i.e., dnaA, gidAB, and mioC, were previously shown to be affected by methylation and the eclipse in synchronized cultures (25, 35). In our nonsynchronized cultures, we observed no significant dam- or _seqA-_dependent variation in expression of the same genes. This suggests that a temporary shut-off after initiation is compensated for by increased transcription throughout the remainder of the cell cycle. Among the individual genes requiring methylation for full expression is flu, which encodes antigen 43. The level of expression was increased 20-fold by overproduction of Dam. This result is consistent with the requirement that methylation of an otherwise unmethylated GATC site in the promoter region is necessary for maximal transcription. This methylation prevents binding of the OxyR transcriptional repressor (36). The galactitol (gat) operon, consisting of gatYZABCD, required methylation for full transcription. Interestingly, the SeqA protein was also required for full activity of this operon and transcription could not be increased further by overmethylation. The gat promoter region contains one GATC site, which may have to be methylated for maximal promoter activity. However, the mechanism of SeqA action on this operon remains obscure.

A remarkable finding was that the transcription profiles of the seqA mutant and the Dam overproducer were almost identical. Because Dam overproduction did not result in down-regulation of seqA, we favor a model in which Dam and SeqA compete for binding hemimethylated DNA behind the replication fork. In SeqA-deficient and Dam-overproducing cells, less hemimethylated DNA would persist than in WT cells. Therefore, the overall methylation status of their chromosomes would be similar. This could explain why these cells behave similarly with respect to repression and derepression of a large number of unrelated genes. Because most of these genes do not contain GATC sequences in their promoter regions (Table 3), we favor a role for SeqA as a DNA structural protein as suggested from previous studies (14, 37, 38) that is related to the increased negative superhelicity of chromosomes in seqA cells (16). We assume that SeqA initiates the process on hemimethylated DNA and other proteins act on methylated DNA to continue organizing the nucleoid.

The chromosome in E. coli is organized in about 50 DNA loops attached to a central structure (39). This number is fairly close to the number of SeqA/Dam domains we observed (≈30; Fig. 5), and it is tempting to speculate that they are the same. This would imply that the SeqA protein normally serves to counteract excessive negative supercoiling within each of the anchored loops. Because the location of seqA/Dam domains correlated with the overall transcription profile along the chromosome (Fig. 5), it is conceivable that they are dictated by regions of the chromosome having intense transcriptional activity alternating with regions of low transcription.

Regions of high gene expression in WT cells showed decreased expression in SeqA-deficient or Dam-overproducing cells, whereas regions with low gene expression in WT cells had increased expression in SeqA-deficient or Dam-overproducing cells. For seqA cells, this may result from increased negative superhelicity of the chromosome (16). This is likely to facilitate open complex formation by RNA polymerase on promoters in general. Increased transcription initiation of genes that normally have a low basal expression would engage a large number of RNA polymerases in their transcription. This titration of RNA polymerases to poorly transcribed genes leads to a decrease in initiation of transcription of genes that are normally highly transcribed because the total number of RNA polymerases presumably does not change (40).

The similar transcription profiles in _seqA-_deficient and Dam-overproducing cells strongly supports the idea that in WT cells, SeqA exerts its function in nucleoid organization through interaction with hemimethylated DNA. On the other hand, because the SeqA protein does not interact with unmethylated DNA in vitro (13, 41), it was surprising that we found no resemblance between dam and seqA mutant cells. This may indicate that other protein(s) can carry out the function of SeqA in dam mutant cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erik Boye for critical reading of the manuscript, Feng He for help with the Affymetrix equipment, Tom Gingeras (Affymetrix) for suggestions about initial data analysis, and anonymous reviewers for suggestions. This work was supported by grants from the Danish National Sciences Research Foundation (to A.L.-O.) and the Novo Nordisk Foundation (to A.L.-O.), and by Grant GM63790 from the National Institutes of Health (to M.G.M.).

References

- 1.Geier G E, Modrich P. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:1408–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stancheva I, Koller T, Sogo J M. EMBO J. 1999;18:6542–6551. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell J L, Kleckner N. Gene. 1988;74:189–190. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marinus M G. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Neidhardt F C, Curtiss R III, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Brooks Low K, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1996. pp. 782–791. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russell D W, Zinder N D. Cell. 1987;50:1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Messer W, Noyer-Weidner M. Cell. 1988;54:735–737. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)90911-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oka A, Sugimoto K, Takanami M, Hirota Y. Mol Gen Genet. 1980;178:9–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00267207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Freiesleben U, Krekling M A, Hansen F G, Løbner-Olesen A. EMBO J. 2000;19:6240–6248. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.6240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu M, Campbell J L, Boye E, Kleckner N. Cell. 1994;77:413–426. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boye E, Stokke T, Kleckner N, Skarstad K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12206–12211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Freiesleben U, Rasmussen K V, Schaechter M. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:763–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brendler T, Sawitzke J, Sergueev K, Austin S. EMBO J. 2000;19:6249–6258. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.22.6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slater S, Wold S, Lu M, Boye E, Skarstad K, Kleckner N. Cell. 1995;82:927–936. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiraga S, Ichinose C, Niki H, Yamazoe M. Mol Cell. 1998;1:381–387. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiraga S, Ichinose C, Onogi T, Niki H, Yamazoe M. Genes Cells. 2000;5:327–341. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weitao T, Nordström K, Dasgupta S. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:494–499. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLeod S M, Johnson R C. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:152–159. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyer M S, Reed R R, Steitz J A, Low K B. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1981;45:135–140. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1981.045.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Løbner-Olesen A, Marinus M G. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:525–529. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.525-529.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marinus M G, Pooteete A, Arraj J A. Gene. 1984;28:123–125. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Meyenburg K, Hansen F G, Atlung T, Boe L, Clausen I G, van Deurs B, Hansen E B, Jorgensen B B, Jorgensen F, Koppes L, et al. In: The Molecular Biology of Bacterial Growth. Schaechter M, Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J, Kjeldgaard N O, editors. Boston: Jones & Bartlett; 1985. pp. 260–281. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark D J, Maaløe O. J Mol Biol. 1967;23:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenow C, Saxena R M, Durst M, Gingeras T R. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:E112. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Løbner-Olesen A, Boye E, Marinus M G. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1841–1851. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bogan J A, Helmstetter C E. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:889–896. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6221989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun R E, O'Day K, Wright A. Cell. 1985;40:159–169. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson K R, Wertman K F, Mount D W, Marinus M G. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;201:14–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00397979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Courcelle J, Khodursky A, Peter B, Brown P O, Hanawalt P C. Genetics. 2001;158:41–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tavazoie S, Church G M. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:566–571. doi: 10.1038/nbt0698-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukhopadhyay S, Chattoraj D K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7142–7147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130189497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boye E, Løbner-Olesen A. Cell. 1990;62:981–989. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90272-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maisnier-Patin S, Nordstrom K, Dasgupta S. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:1371–1382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keener J, Nomura M. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Neidhardt F C, Curtiss R III, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Brooks Low K, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1996. pp. 1417–1431. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang T C, Smith K C. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:1023–1025. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.1023-1025.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell J L, Kleckner N. Cell. 1990;62:967–979. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90271-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haagmans W, van der Woude M. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:877–887. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawitzke J, Austin S. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:786–794. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weitao T, Nordström K, Dasgupta S. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:157–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Worcel A, Burgi E. J Mol Biol. 1972;71:127–147. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jensen K F, Pedersen S. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:89–100. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.2.89-100.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brendler T, Austin S. EMBO J. 1999;18:2304–2310. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plumbridge J, Soll D. Biochimie. 1987;69:539–541. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(87)90091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marinus M G. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;200:185–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00383334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]