T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type-1 inflammation (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2009 Dec 1.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Immunol. 2009 May 3;10(6):595–602. doi: 10.1038/ni.1731

Abstract

Several subsets of Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells work in concert to maintain immune homeostasis. However, the molecular bases underlying the phenotypic and functional diversity of Treg cells remain obscure. We show that in response to interferon-γ, Foxp3+ Treg cells upregulated the T helper 1 (TH1)-specifying transcription factor T-bet. T-bet promoted expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 on Treg cells, and T-bet+ Treg cells accumulated at sites of TH1-mediated inflammation. Furthermore, T-bet expression was required for the homeostasis and function of Treg cells during type-1 inflammation. Thus, within a subset of CD4+ T cells, the activities of Foxp3 and T-bet are overlaid, resulting in Treg cells with unique homeostatic and migratory properties optimized for suppression of TH1 responses in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

CD4+ T cells adopt one of several functional fates defined by their cytokine production and/or suppressive activity. This functional specialization is due to differential expression of transcription factors that initiate distinct programs of gene expression controlling cytokine production and migration1. For instance, interferon (IFN)-γ ( http://www.signaling-gateway.org/molecule/query?afcsid=A001238)-producing CD4+ T helper type-1 (TH1) cells are required for the elimination or control of many intracellular pathogens2, and the transcription factor T-bet is thought to be both necessary and sufficient for TH1 cell differentiation3. Accordingly, T-bet directly activates transcription of a set of genes important for TH1 cell function, including those encoding IFN-γ and the chemokine receptor CXCR3 (http://www.signaling-gateway.org/molecule/query?afcsid=A000635)3, 4. Conversely, the transcription factor Foxp3 (http://www.signaling-gateway.org/molecule/query?afcsid=A002750) is required for the development of CD4+ regulatory T (Treg) cells5. Within cells, Foxp3 coordinates a transcriptional program resulting in the expression of genes important for their regulatory activity, while preventing production of pro-inflammatory cytokines6, 7. The importance of Foxp3+ Treg cells in maintaining immune tolerance is highlighted by the rapid and fatal autoimmunity that develops in Foxp3-deficient mice and humans8-11.

Although beneficial during infection, strong TH1 responses must be counterbalanced to prevent unwanted tissue destruction and immunopathology. In addition, many autoimmune diseases are thought to result from dysregulated TH1 responses to self-antigens. The mechanisms used to dampen TH1 immune responses in vivo are complex and involve multiple cell types. For example, ‘self-regulation’ via interleukin (IL)-10 produced by highly activated TH1 cells is required for limiting immunopathology during several persistent parasitic infections12, 13. However, Foxp3+ Treg cells are also essential for the proper regulation of TH1 responses in vivo, and can modulate TH1-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity responses14, inhibit TH1 responses during autoimmunity15, and prevent pathogen clearance during persistent intracellular infection16, 17. In addition, loss of Treg cells results in uncontrolled TH1 responses, further demonstrating the important and non-redundant function of Treg cells in dampening type-1 inflammation18, 19.

Treg cells can be divided into several subsets based on their differential expression of surface homing receptors, and can be readily identified in both lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues20, 21. Accordingly, blocking their migration to specific anatomical locales results in development of immunopathology in the contexts of autoimmunity, infection and transplantation21-25. Treg cells can also be partitioned into distinct subsets based on their use of a variety of immunosuppressive mechanisms5. For example, IL-10 produced by Treg cells is required for the control of inflammatory responses at mucosal surfaces, but is dispensable for suppression of deleterious immune responses in other tissues26. Although these findings highlight the phenotypic and functional diversity of Treg cells, the contributions made by the various Treg cell subsets to the control of different types of immune responses remain poorly understood. Additionally, little is known about the external cues and intracellular factors responsible for the differentiation and function of distinct Treg cell populations.

Our data demonstrate that the TH1-specifying transcription factor T-bet controls Treg cell migration, homeostasis and function during type-1 inflammatory responses, and that the IFN-γ-receptor (IFN-γR) plays a key role in the induction of T-bet expression by Treg cells. These results provide new insights into the molecular bases for the phenotypic and functional diversity of Treg cells, and demonstrate that like conventional CD4+ effector T cells, Foxp3+ Treg cells undergo peripheral differentiation in response to the cytokine environment by altering their homeostatic and migratory properties, thereby enabling them to effectively function during strong TH1 responses.

RESULTS

A subset of CD4+Foxp3+ T cells expresses T-bet

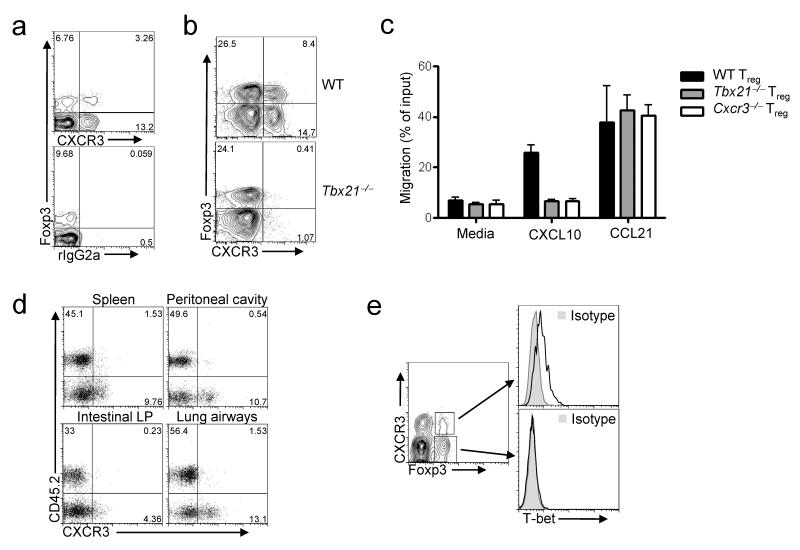

In addition to being expressed by TH1 cells, the chemokine receptor CXCR3 is also found on a subset of Foxp3+CD4+ cells (Fig. 1a)20. The CXCR3 ligands CXCL9, 10 and 11 are all induced by IFN-γ and enable the efficient recruitment of CXCR3+ cells to sites of type-1 inflammation27-29. Based on this migratory potential, we hypothesized that CXCR3+ Treg cells may be molecularly specialized to effectively inhibit TH1 responses. CXCR3 expression in TH1 cells generated in vitro is T-bet dependent, and T-bet directly binds to and transactivates the Cxcr3 promoter in transfected cells4, 30. Therefore, to determine if expression of CXCR3 in Treg cells is also T-bet-dependent, we examined T-bet-deficient (_Tbx21_-/-) mice. There was a near complete absence of CXCR3+CD4+Foxp3+ cells in these animals, whereas expression of other homing receptors, including P- selectin ligands, CD103 and CCR6, was similar in wild-type and T-bet-deficient Treg cells (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1 online). Accordingly, T-bet-deficient Treg cells failed to migrate toward the CXCR3 ligand CXCL10 in vitro, whereas their responses to the CCR7 ligand CCL21 and the CXCR4 ligand CXCL12 were unaltered (Fig.1c and data not shown).

Figure 1. CXCR3 expression on Treg cells is T-bet-dependent.

(a,b) Representative flow cytometric analysis of CXCR3 and Foxp3 expression by splenocytes isolated from wild-type (WT) mice, (a) or age-matched WT and _Tbx21_–/- mice (b). Plots are gated on CD4+ splenocytes. rIgG2a, isotype control. Numbers display the frequency of cells expressing the indicated markers. Data are representative of greater than six mice analyzed in this fashion. (c) Migration of CD4+Foxp3+ splenocytes isolated from the indicated mice in response to media alone, 100nM CXCL10 or 100nM CCL21 in a transwell chemotaxis assay. Data are mean and s.d. of triplicate measurements. (d) CD45.2 and CXCR3 expression on CD4+Foxp3+ cells recovered from the indicated tissues of recipients of a mixture of CD45.1+ WT and CD45.2+ _Tbx21_–/– BM. Numbers depict the percent of cells positive for the indicated markers. Data are representative of three independent experiments with four mice analyzed per experiment. (e) T-bet expression (open histograms) in CD4+Foxp3+CXCR3+ or CD4+Foxp3+CXCR3- splenocytes. Histograms (right) correspond to indicated gates (left). Data are representative of greater than ten mice analyzed in this fashion.

The lack of CXCR3+ Treg cells in T-bet-deficient mice suggests that T-bet directly induces CXCR3 expression in these cells. Alternatively, Treg cells may upregulate CXCR3 in a T-bet-independent manner during TH1 responses, and the absence of CXCR3+ Treg cells in T-bet-deficient mice may be a consequence of the impaired TH1 cell development in these animals. To distinguish between these possibilities, we generated mixed bone marrow (BM) chimeras by transplanting a 1:1 ratio of BM cells from wild-type (CD45.1+) and T-bet-deficient (CD45.2+) donors into irradiated _Rag1_-/- recipients. In the resulting mixed chimeric animals, CXCR3+ Treg cells were derived almost entirely from the CD45.1+ wild-type donor, demonstrating that T-bet is required in a cell-intrinsic manner for Treg cell expression of CXCR3 (Fig. 1d). Accordingly, T-bet mRNA was enriched in CXCR3+ Treg cells, and T-bet protein was detected exclusively within the CXCR3+ Treg cell subset by flow cytometry (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 2 online).

Treg cells upregulate T-bet during type-1 inflammation

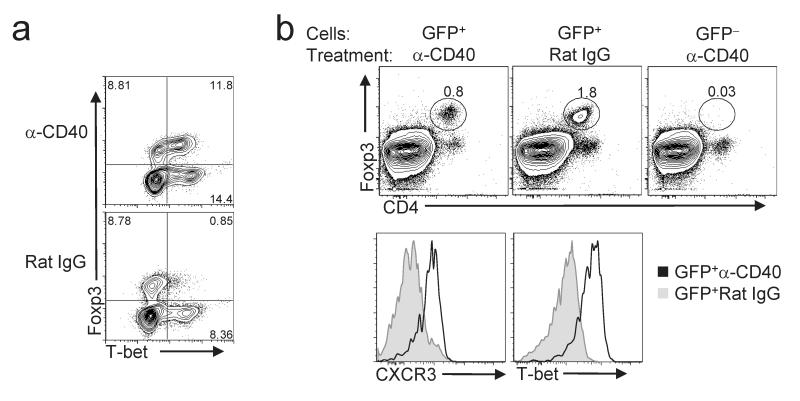

The frequency of CXCR3+ Treg cells was significantly lower in the thymus than in the spleen, and the percentage of splenic Treg cells expressing CXCR3 increased with age (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). This suggests that Treg cells upregulate T-bet in response to specific peripheral cues, likely associated with induction of type-1 inflammation. To determine if T-bet+ Treg cells differentiate and/or expand during strong TH1-promoting conditions in vivo, we injected wild-type mice with an agonistic CD40-specific antibody. This treatment induces strong TH1 responses in vivo, and protects Balb/c mice infected with Leishmania major by converting their characteristic TH2 response to a protective TH1 response31. Indeed, both the frequency and absolute number of T-bet+CXCR3+ Treg cells in spleen and lymph nodes were markedly increased in anti-CD40-treated mice compared with control mice given rat IgG (Fig. 2a and data not shown). The increase in T-bet+ Treg cells in anti-CD40 treated animals was not simply a byproduct of enhanced proliferation, as robust proliferation induced by IL-2 immune complexes (IL-2C) did not increase the proportion of CXCR3+ Treg cells (Supplementary Fig. 4 online)32. To determine if T-bet+ Treg cells are derived from T-bet-Foxp3+ precursors, we sorted CD4+Foxp3+CXCR3-CD62L+ cells from the spleen and peripheral lymph nodes of reporter mice with a GFP cassette knocked in to the Foxp3 locus (Foxp3_gfp_ mice) and then transferred these cells into mice lacking endogenous T cells (TCRβδ-KO mice) (Fig. 2b). Unlike rat IgG treatment, anti-CD40 treatment resulted in upregulation of T-bet and CXCR3 expression in the majority of transferred Treg cells (Fig. 2c). Notably, anti-CD40 treatment did not induce Foxp3 expression in transferred CD4+Foxp3-CXCR3-CD62L+ T cells. Thus, TH1-inducing conditions promote de novo induction of T-bet expression within Foxp3+T-bet- Treg cells, and in this experimental system T-bet+ Treg cells were not peripherally induced from naïve CD4+Foxp3- cells.

Figure 2. T-bet+ Treg cells upregulate T-bet in vivo following anti-CD40 treatment.

(a) Analysis of T-bet and Foxp3 expression in splenocytes from mice treated with anti-CD40 (top) or rat IgG (bottom). Plots are gated on CD4+ cells. Numbers in plots represent the percentage of cells positive for the indicated markers. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (b) (Top) Splenocytes from TCRβδ-KO recipients of the indicated cells and subjected to the indicated treatment were analyzed by flow cytometry. Dot plots are gated on lymphocytes. Histograms display CXCR3 and T-bet expression in CD4+Foxp3+ cells isolated from anti-CD40- (open histograms) or rat IgG- (shaded histograms) treated mice as indicated. Numbers in dot plots indicate the percentage of Foxp3+CD4+ cells of total lymphocytes. Data are representative of two independent experiments with three mice per group.

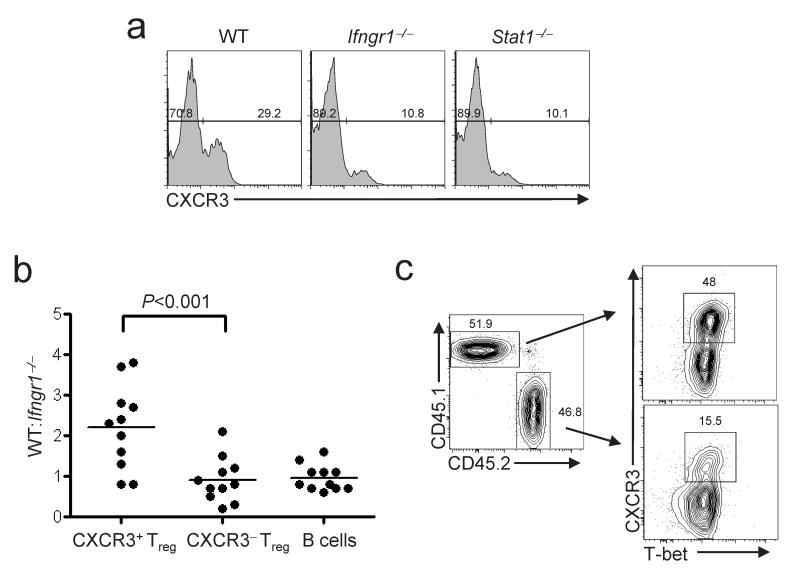

T-bet is first expressed in developing TH1 cells following T cell receptor ligation coupled with signaling through the IFN-γ receptor (IFN-γR) via its associated signaling adaptor STAT133. Additionally, stable T-bet expression and full commitment to the TH1 lineage depends on IL-12 signaling through its cognate receptor34. To determine if T-bet induction in Treg cells occurs through a similar mechanism, we analyzed CD4+Foxp3+ cells isolated from mice lacking IFN-γR1, STAT1 and IL-12p40. Interestingly, there was a substantial reduction in the frequency of CXCR3+T-bet+ Treg cells in mice lacking either STAT1 or IFN-γR1 (Fig 3a). In contrast, relative to age-matched controls, there was no decrease in the fraction of CXCR3+ Treg cells in IL-12p40-deficient mice (data not shown). In addition, mice lacking either IL-4 or STAT6--two molecules critical for TH2 cell differentiation--also contained normal frequencies of CXCR3+ Treg cells (Supplementary Fig. 5 online). Together, these findings indicate that T-bet expression in Treg cells is induced during TH1 responses by an IFN-γ-dependent, IL-12-independent signaling pathway. To determine if IFN-γR expression in Treg cells is required for optimal expression of T-bet and CXCR3, we constructed mixed BM chimeras using wild-type and _Ifngr1_-/- donors, and determined the contribution of each donor to various lymphocyte populations. Whereas wild-type and _Ifngr1_–/– BM contributed equally to the generation of B cells and CXCR3- Treg cells, CXCR3+ Treg cells were derived predominantly from the wild-type donor (Fig 3b,c), demonstrating that IFN-γ responsiveness is required for optimal expression of T-bet and CXCR3 by Treg cells. Together, these data provide a molecular link between IFN-γ produced during strong type-1 inflammatory responses and expression of T-bet by Treg cells, and support the hypothesis that T-bet is selectively induced in Treg cells during TH1-mediated inflammation.

Figure 3. IFN-γR and STAT1 are promote expression of T-bet and CXCR3 by Treg cells.

(a) CXCR3 expression on splenocytes from WT, _Ifngr1_–/–, or _Stat1_–/– mice as indicated (n≥ three per genotype). Histograms are gated on CD4+Foxp3+ cells. Numbers indicate the percent of CXCR3+ cells among total CD4+Foxp3+. (b) Graph depicts the ratio of WT:_Ifngr1_–/–-derived lymphocytes among CXCR3+CD4+Foxp3+, CXCR3-CD4+Foxp3+ or CD4-B220+ peripheral blood lymphocytes of 11 mixed BM chimeras. Each point represents an individual mouse. Statistical significance was determined using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA. A Bonferroni post-test was used to obtain the _P_-value for the indicated pairwise comparison. (c) CXCR3 and T-bet expression on splenocytes isolated from a WT:_Ifngr1_–/– BM chimera. Plots are gated on CD4+Foxp3+ cells from WT-derived (CD45.1+) or _Ifngr1_–/– -derived (CD45.2+) BM as indicated. Numbers in dot plots indicate the percent of cells positive for CXCR3. Data are representative of four mice analyzed in this fashion.

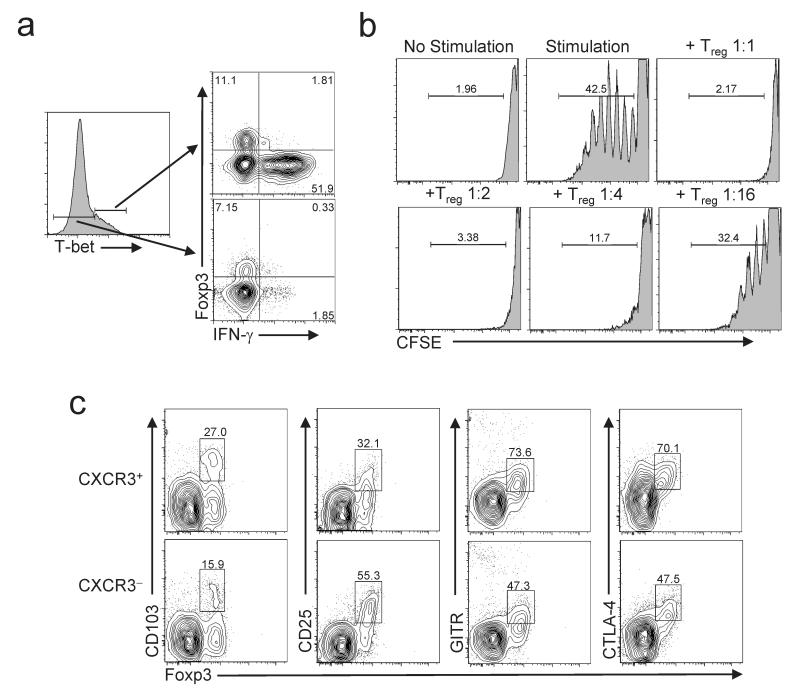

Functional characterization of T-bet+ Treg cells

Within CD4+ T cells, T-bet and Foxp3 direct distinct transcriptional programs that can result in opposing functional outcomes. T-bet binds to and transactivates the Ifng locus, and is required for IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells35. However, Foxp3 can suppress IFN-γ expression, and Treg cells do not generally produce pro-inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, we examined IFN-γ production by splenocytes isolated from Foxp3_gfp_ mice following in vitro stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (Fig 4a). As expected, IFN-γ production among Foxp3- cells was largely restricted to the T-bet+ population. However, very few Foxp3+T-bet+ cells produced IFN-γ. Additionally, CXCR3+ Treg cells sorted from anti-CD40-treated Foxp3_gfp_ mice efficiently suppressed the proliferation of CD4+CD25- T cells in vitro, demonstrating their suppressive capacity (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. Functional characterization of T-bet+ Foxp3+ Treg cells.

(a) IFN-γ and Foxp3 expression by T-bet+CD4+ (top right) and T-bet-CD4+ (bottom right) lymphocytes isolated from WT mice following stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. Left histogram is gated on total CD4+ cells, and indicates gates used to define the populations depicted in the dot plots. Numbers in plot indicate the percent of cells positive for the indicated markers. Data are representative of greater than five mice analyzed in this fashion. (b) Proliferation of CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25- T cells incubated with irradiated splenocytes, anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, with or without varying concentrations of CXCR3+ Treg cells. Numbers above histograms indicate Treg:Teff cell ratio in each culture. No stimulation, control without irradiated splenocytes and stimulatory antibodies. Numbers indicate the percent of Teff cells that are CFSE-. (c) Expression of the indicated markers on gated CD4+CXCR3+ (top) or CD4+CXCR3- (bottom) splenocytes from WT mice. Numbers represent the frequency of cells positive for each marker as a fraction of total CD4+Foxp3+ cells. Data are representative of three mice analyzed in this fashion.

CXCR3+ Treg cells expressed high amounts of GITR, CTLA-4 and CD103, and low amounts of CD25, consistent with the phenotype of ‘effector/memory-like’ Treg cells (Fig. 4c)20. Accordingly, CXCR3+ Treg cells contained abundant mRNA for the Treg cell-associated effector molecules IL-10, TGF-β and granzyme B (Supplementary Fig. 6 online). Furthermore, sorted Foxp3+CXCR3+ cells maintained expression of both CXCR3 and T-bet for at least two weeks following adoptive transfer into lympho-replete hosts, indicating that T-bet expression is a stable characteristic of this Treg cell subset (Supplementary Fig. 7 online and data not shown).

T-bet regulates Treg cell homeostasis

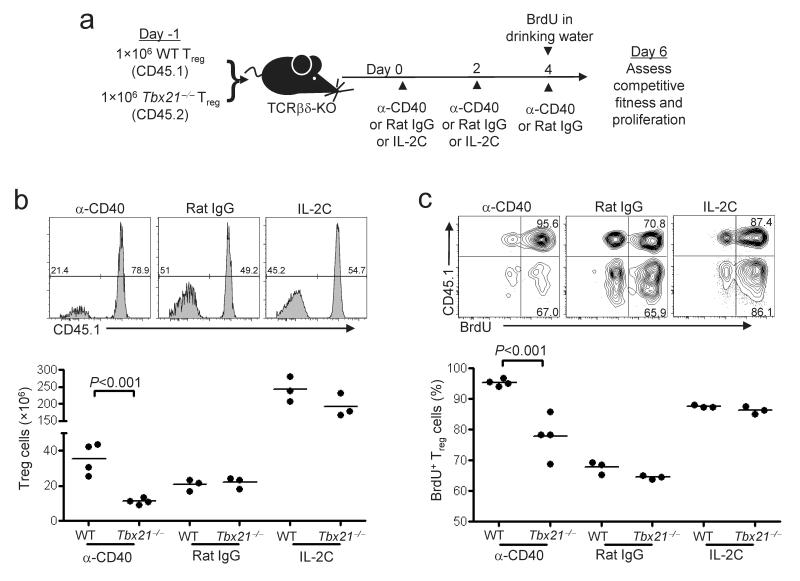

T-bet controls the proliferation and selection of developing TH1 cells in vivo1, 34. As such, we hypothesized that T-bet may be important for Treg cell proliferation and/or survival in the TH1-promoting conditions induced by anti-CD40 treatment. To test this, we co-injected purified CD45.2+ T-bet-deficient and CD45.1+ wild-type Treg cells into TCRβδ-KO mice, treated the recipient animals with anti-CD40, IL-2C, or rat IgG and examined the frequency and absolute number of each population in the spleen of recipient animals one week later (Fig 5a). Consistent with a role for T-bet in regulating Treg cell homeostasis, T-bet-deficient Treg cells were outcompeted by wild-type cells following anti-CD40 treatment (Fig. 5b). Indeed, the absolute number of T-bet-deficient Treg cells recovered from anti-CD40-treated mice was lower than in rat IgG-treated controls, suggesting that T-bet promotes the survival and/or proliferation of Treg cells in type-1 inflammatory conditions (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, both wild-type and T-bet-deficient Treg cells underwent robust expansion in animals given IL-2C, demonstrating that the failure of T-bet-deficient Treg cells to expand in anti-CD40-treated mice was not due to a general inability to survive and proliferate in vivo.

Figure 5. Decreased proliferation of T-bet-deficient Treg cells following anti-CD40 treatment.

(a) Experimental design showing cell transfer and treatment schedule. Briefly, a mixture of CD45.1+ WT and CD45.2+ _Tbx21_–/– Treg cells were injected into TCRβδ-KO mice, followed by treatment with the indicated antibodies. BrdU was added to the drinking water when indicated. (b) CD45.1 expression on splenocytes of recipient mice was analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms are gated on Foxp3+CD4+TCRβ+B220- cells, and numbers indicate the percent of cells positive and negative for CD45.1. Graphs show absolute numbers of WT- and _Tbx21_–/–-derived Treg cells recovered from the spleens of recipient mice. Each point represents an individual treated mouse. (c) BrdU incorporation by splenocytes of recipient mice was analyzed by flow cytometry. Dot plots are gated on Foxp3+CD4+TCRβ+B220- splenocytes. Numbers in plots indicate percentage of BrdU+ cells among total WT- (CD45.1+) or _Tbx21_–/–-derived (CD45.1-) Treg cells. Graphs depict the frequency of BrdU+ cells among WT and _Tbx21_–/–-derived Treg cell populations. For b and c, statistical significance was determined using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA. Bonferroni post-tests were used to obtain the _P_-values for the indicated pairwise comparisons. Data are representative of three independent experiments with three or greater mice per group

To directly compare the proliferation of wild-type and T-bet-deficient Treg cells, we administered the nucleotide analogue 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) in the drinking water of recipient mice during the final 48 hours of anti-CD40, IL-2C or rat IgG treatment (Fig. 5c). Due to the lymphopenic environment present in the TCRβδ-KO animals, the majority of both wild-type and T-bet-deficient Treg cells incorporated BrdU in rat IgG-treated mice. Treatment with IL-2C further enhanced proliferation of both populations, consistent with their similar accumulation under these conditions. In contrast, the proliferative response of T-bet-deficient Treg cells following anti-CD40 treatment was significantly attenuated. The T-bet target genes CXCR3 and IL-12Rβ2 have been implicated in TH1 cell differentiation and selection34, 36, 37. However, proliferation of both CXCR3- and IL-12Rβ2-deficient Treg cells was equivalent to wild-type following anti-CD40 treatment (Supplementary Fig. 8 online).

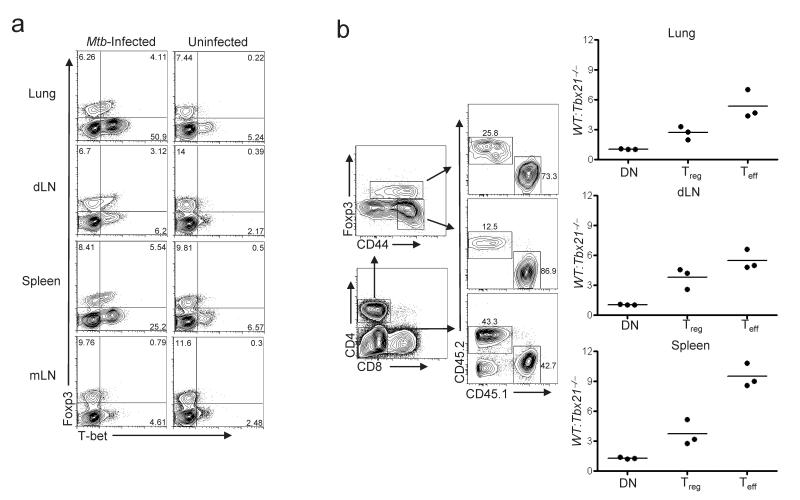

Because T-bet is induced in Treg cells and controls their proliferation following anti-CD40 treatment, we reasoned that T-bet may also be important for Treg cell fitness during persistent infections dominated by TH1 immune responses. Following aerosol infection with Mtb, both TH1 effector cells and Treg cells proliferate in the draining mediastinal lymph node (dLN) and traffic in parallel to granulomas in the lungs, a nidus of IFN-γ-mediated inflammation17, 38. The “balanced” responses of TH1 cells and Treg cells established within pulmonary granulomas leads to the control, but not the eradication, of tuberculous bacilli. In _Mtb_-infected mice, T-bet+ Treg cells were highly enriched in three principle sites of microbial replication: the lungs, the dLN and the spleen (Fig. 6a). In contrast, few T-bet+ Treg cells were found in the uninvolved mesenteric lymph nodes (mLN), nor did they accumulate in the lungs of mice with chronic TH2-mediated pulmonary inflammation caused by overexpression of the pro-allergic cytokine thymic stromal lymphopoietin (SPC-Tslp mice, Supplementary Fig. 9 online)39.

Figure 6. Impaired homeostasis of T-bet-deficient Treg cells during persistent Mtb infection.

(a) T-bet and Foxp3 expression on cells isolated from the indicated tissues of an _Mtb_-infected mouse (left) or an uninfected age-matched control (right). Plots are gated on CD4+ T cells. Numbers display the percent of cells in each of the indicated quadrants. Data are representative of five independent experiments. (b) (Left) Recipients of a mixture of WT (CD45.1+) and _Tbx21_–/– (CD45.2+) BM were infected with Mtb for 105 days. Cells isolated from the indicated organs were analyzed by flow cytometry. Contour plots depict gating strategy, with numbers indicating the percent of cells positive for the indicated markers. Graphs depict the ratio of WT and _Tbx21_–/–-derived cells among gated CD4-CD8- DN, CD4+Foxp3+ Treg and CD4+Foxp3-CD44hi Teff populations. Each point represents a value from an individual infected BM chimera. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n=3 per experiment).

To determine if T-bet expression by Treg cells is important for their competitive fitness during persistent infection, we constructed mixed BM chimeras using wild-type and T-bet-deficient donors, and calculated the ratio of wild-type:T-bet-deficient Treg cells present in the lungs, dLN and spleen following Mtb infection (Fig. 6b). As control populations, we examined the ratio of wild-type:T-bet-deficient CD4+CD44hiFoxp3- effector T cells (Teff), and CD4-CD8- (DN) cells, which are predominantly B cells. There was a 3-5 fold enrichment of wild-type compared to T-bet-deficient Treg cells in the tissues of infected animals, indicating that T-bet-deficient Treg cells were outcompeted by wild-type cells during Mtb infection (Fig 6b). T-bet-deficient CD4+Foxp3-CD44hi effector T cells were also outcompeted by wild-type effector T cells, consistent with the obligate role of T-bet in directing TH1 cell differentiation and accumulation34. In contrast, wild-type and T-bet-deficient DN cells were present in a 1:1 ratio in each tissue, demonstrating equal engraftment of hematopoietic precursors. These data corroborate our results in anti-CD40-treated mice and demonstrate that T-bet regulates the homeostasis of Treg cells during the strong TH1 responses elicited by Mtb infection.

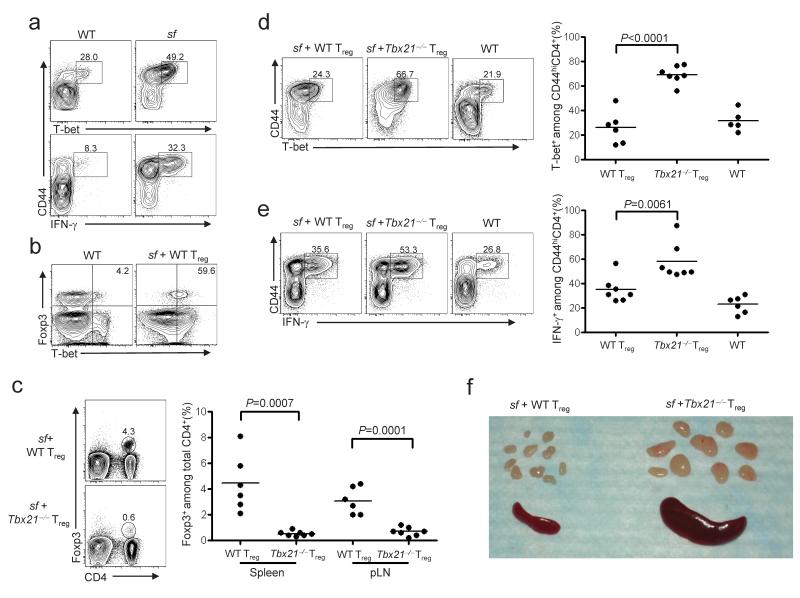

Functional impairment of T-bet-deficient Treg cells

T-bet deficient Treg cells can block T cell proliferation in vitro40, and function in vivo in experimental models of asthma and colitis41-43. However, their ability to specifically regulate TH1 responses has not been directly examined. Therefore, we compared the ability of wild-type and T-bet-deficient Treg cells to control TH1 responses following transfer into Foxp3-deficient scurfy (sf) mice. Due to a spontaneous mutation in Foxp3, these animals lack functional Treg cells and succumb to severe multi-organ autoimmunity associated with an accumulation of CD4+T-bet+ TH1 cells that produce IFN-γ (Fig. 7a)44. Transfer of purified Treg cells into neonatal sf mice prevents disease; thus, this is a sensitive experimental system to examine the homeostasis and function of Treg cells in vivo21. Consistent with the strong TH1 responses observed in sf mice, we found that most wild-type Treg cells recovered from the spleens of recipient sf animals expressed T-bet (Fig. 7b). However, compared to mice given wild-type cells, the frequency of CD4+Foxp3+ cells recovered from recipients of T-bet-deficient Treg cells was significantly reduced (Fig. 7c). Additionally, there was an increase in the fraction of CD4+CD44hi effector T cells expressing T-bet and producing IFN-γ in recipients of T-bet-deficient Treg cells (Fig. 7d,e). In contrast, the frequency of IL-4 and IL-17 producing CD4+ T cells did not differ between sf recipients of wild-type or T-bet-deficient Treg cells (Supplemental Fig. 10 online). Moreover, whereas all animals receiving wild-type Treg cells remained healthy throughout the 60 day experiment, 7 out of 10 sf mice given T-bet-deficient Treg cells failed to thrive, appeared runted, and displayed other symptoms of inflammatory disease such as lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly (Fig. 7f, Supplemental Fig. 11, and Supplemental Table 1 online). Together, these data demonstrate that T-bet is essential for Treg cell homeostasis and control of TH1 responses in sf mice.

Figure 7. T-bet expression in Treg cells is critical for control of TH1-mediated inflammatory responses.

(a) CD44 and T-bet expression (top) or IFN-γ production (bottom) by splenocytes isolated from age-matched WT or scurfy (sf) mice, as measured by flow cytometry. Plots are gated on CD4+Foxp3- cells. Numbers in plots indicate the percent of T-bet+ (top) or IFN-γ+ (bottom) cells among total CD44hi CD4+Foxp3-cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (b) T-bet and Foxp3 expression by splenocytes isolated from age-matched WT mice or sf mice given WT Treg cells. Plots are gated on CD4+CD8- lymphocytes. Numbers in plots indicate the percentage of CD4+Foxp3+ cells expressing T-bet. Data are representative of six independent experiments. (c) Cells isolated from the spleen and peripheral lymph nodes (pLN) of sf neonate recipients of WT or _Tbx21_-/- Treg cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Numbers in plots indicate fraction of Foxp3+ T cells among total CD4+ reg splenocytes. (d, e) Flow cytometric and quantitative analysis of splenocytes isolated from sf mice given WT or _Tbx21_–/– Treg cells, or from age-matched WT mice. Splenocytes in e were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin prior to analysis. Plots are gated on CD4+Foxp3- cells. Numbers in plots display percentage of T-bet+ (d) and IFN-γ+ (e) cells among total CD4+Foxp3-CD44hi cells. (f) Photograph of representative spleen and peripheral LNs isolated from 6 week old sf mice given WT (left) or _Tbx21_–/– (right) Treg cells as neonates. Representative of six independent experiments. For c, d and e, each point represents an individual mouse, and significance was measured using two-tailed, unpaired student’s t tests.

Real-time PCR analysis of sorted Foxp3+ cells showed only modest (∼2-fold) reductions in expression of the immunosuppressive cytokines TGF-β and IL-10 in T-bet-deficient compared to wild-type Treg cells (data not shown). Thus, impaired expression of these genes is unlikely to account for the inability of T-bet-deficient Treg cells to control TH1 responses in sf mice. Instead, our data indicate that T-bet functions largely to endow Treg cells with the homeostatic and migratory properties required for the suppression of strong TH1 responses in vivo.

Discussion

We identified the TH1-associated transcription factor T-bet as a key regulator of the migration, proliferation and survival of Treg cells during TH1-mediated immune responses in vivo. These data have several important implications for understanding Treg cell-mediated immunoregulation and the functional differentiation of CD4+ T cells. First, they demonstrate that like conventional naïve CD4+ T cells, Treg cells undergo molecular differentiation in response to the cytokine environment, resulting in their phenotypic and functional specialization. In addition, they show T-bet is important not only for the differentiation of TH1 cells, but also for the control and regulation of TH1 responses; thus the role of T-bet in coordinating type-1 inflammation in vivo is more complicated than previously appreciated. Finally, by demonstrating that Foxp3 and T-bet operate within the same cell to produce a unique functional outcome, our data challenge current models which posit that the functional specialization of CD4+ T cells is due to differential and exclusive expression of a limited set of ‘master’ transcription factors.

T-bet appears to control multiple aspects of Treg cell biology during type 1-inflammatory responses. By inducing expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR3, T-bet can help promote Treg cell migration to sites of TH1-mediated inflammatory responses. CXCR3 is expressed by TH1 cells, by nearly all activated CD8+ T cells, and by the majority of natural killer (NK) and NKT cells. During TH1 responses, CXCR3 expression facilitates efficient recruitment of these effector populations in response to the IFN-γ-inducible CXCR3 ligands. Indeed, we found that CXCR3+T-bet+ Treg cells accumulate at sites of TH1-mediated inflammation during persistent Mtb infection. Although the importance of CXCR3 in inflammatory cell migration depends on the model used and the tissue examined, two recent reports have demonstrated a critical role for CXCR3-mediated trafficking of Treg cells to the central nervous system and liver, highlighting the importance of T-bet-induced CXCR3 expression in the localization and function of Treg cells45, 46.

The molecular mechanisms by which T-bet controls the homeostasis of Treg cells during TH1 inflammation are not clear. Early in TH1 cell differentiation, STAT1-induced T-bet confers responsiveness to the cytokine IL-1234. Acting via STAT4, IL-12 then induces growth and survival of developing TH1 cells. However, we found normal numbers of T-bet+CXCR3+ Treg cells in IL-12p40-deficient mice, and Treg cells lacking IL-12Rβ2 showed no homeostatic defect in anti-CD40 treated mice. T-bet also regulates the development and homeostasis of both NK and NKT cells, largely through induction of CD122, which allows these cells to respond to the cytokine IL-1547. CD122 is also a component of the high-affinity IL-2 receptor, and is required for the differentiation and homeostasis of Treg cells48. However, T-bet-deficient Treg cells proliferated and expanded normally following IL-2C treatment, and thus it is unlikely that impaired IL-2 responsiveness underlies their altered homeostasis. Instead, T-bet likely controls the homeostasis of TH1 cells, NK and NKT cells, and Treg cells by distinct mechanisms. T-bet may act in Treg cells by directly controlling expression of cell cycle or anti-apoptotic genes4, or by conferring sensitivity to undefined growth and survival factors that regulate Treg cell homeostasis primarily during type-1 inflammation.

Recently, the transcription factor interferon-regulatory factor-4 (IRF-4), which functions in TH2 cell differentiation, was shown to be required for Treg cell-mediated control of TH2 responses in vivo18. Together with our results, these findings indicate that as a general strategy, Treg cells may utilize selective aspects of effector T cell differentiation programs to tune their migratory, homeostatic and functional properties without acquiring pro-inflammatory effector functions. However, whereas IRF-4 appears to be expressed uniformly by nearly all peripheral Treg cells, T-bet is only expressed by a subset of Treg cells defined by surface expression of CXCR3. Additionally, our data suggest a molecular pathway by which Treg cells upregulate T-bet in response to STAT1-mediated IFN-γR signaling. Indeed, recent genome-wide histone methylation analyses indicate that Tbx21 exists in a poised epigenetic state in Treg cells, and can readily be upregulated under TH1-polarizing conditions in vitro49. Collectively, these results demonstrate that Treg cells can sense and respond to the local cytokine environment by undergoing molecular specialization that enables them to function in specific inflammatory settings.

T-bet coordinates TH1 cell development and function by directly inducing expression of genes such as Ifng, Il12rb2, Spp1, Runx3, Hlx and Cxcr3, and by silencing Il4 to block TH2 differentiation1. Interestingly, we noted that CXCR3+ Treg cells express ∼10-20-fold lower amounts of T-bet when compared with fully differentiated CD4+Foxp3-CXCR3+ TH1 cells. The ability of T-bet to bind to particular target loci and promote gene expression may be concentration-dependent4. In addition, Foxp3 can directly repress Ifng expression, and chromatin immunoprecipitation studies detected Foxp3 bound to the Spp1 locus, which encodes the type-1 cytokine osteopontin6, 50. Therefore, we propose that coupled with the direct repressive functions of Foxp3, the low concentration of T-bet in CXCR3+ Treg cells prevents the production of pro-inflammatory TH1 cytokines, while permitting expression of T-bet target genes that influence localization and homeostasis of Treg cells during TH1-mediated inflammatory responses. Consistent with this model, Treg cells that lost Foxp3 expression upregulated T-bet and acquired the ability to produce IFN-γ, suggesting an active role for Foxp3 in preventing full TH1 cell differentiation in Treg cells19.

Our results provide a new framework for understanding how Treg cells sense and respond to strong TH1 responses, and how this leads to their phenotypic differentiation and specialization. Further defining the molecular mechanisms by which T-bet and Foxp3, when present in combination, control the homeostasis, migration and function of Treg cells is essential for determining how Treg cells maintain normal immune homeostasis during TH1 responses in vivo, and for understanding how the activities of two so-called ‘master regulators’ of CD4+ T cell differentiation can be overlaid in the same cell to produce a unique functional outcome.

Supplementary Material

1

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Thompson and K. Smigiel for technical assistance, G. Debes (University of Pennsylvannia), K. Konowski (University of Georgia), and J. Hamerman for comments on the manuscript, and M. Warren for administrative assistance. This work was funded by grants to D.J.C. from the NIH (DK072295, AI067750, and AI069889) and from the Department of Defense (USAMRAA W81XWH-07-0246), and to K.B.U. by a Burroughs-Wellcome Fund Career Award in the Biological Sciences. M.A.K. is the recipient of a training grant from the Department of Immunology at the University of Washington medical school (T32-CA009537).

ONLINE METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6J, Balb/c, B6.129P2-CXCR3_tm1Dgen_/J (_Cxcr3_-/-), B6.129P2-Tcrb tm1Mom Tcrd tm1Mom/J (TCRβδ-KO), B6.129S7-Ifngr1tm1Agt/J (_Ifngr1_-/-) and B6.Cg-Foxp3sf/J (sf) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. B6.SJL-Ptprca/BoyAiTac (CD45.1) mice were purchased from Taconic Farms. Tbx21_-/- and Foxp3_gfp mice (on C57BL/6 background) were generously provided by A. Weinmann and A. Rudensky, respectively (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). _SPC-Tslp, Il4_-/- and _Stat6_-/- mice (on Balb/c background) were provided by S. Ziegler (Benaroya Research Institute, Seattle, WA). Splenocytes from _Stat1_-/- mice were provided by M. Krishna-Kaja. All animals were housed and bred at the Benaroya Research Institute (Seattle, WA) and all experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Benaroya Research Institute Animal Care and Use Committee.

BM chimeras and neonatal transfers

BM cells from the femurs of WT, _Tbx21_-/- and _Ifngr1_-/- mice were obtained and depleted of CD4+ cells using anti-CD4 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). 8×106 cells of a 1:1 mixture of WT (CD45.1) and _Tbx21_-/- (CD45.2) or _Ifngr1_-/- (CD45.2) BM were injected retro-orbitally into RAG1-/- mice following lethal irradiation of 1000 Rad. For neonatal adoptive transfers, CD4+CD25+ cells were isolated from the spleens and LNs of WT or _Tbx21_-/- mice by magnetic separation using a CD4 T cell isolation kit (Invitrogen), followed by CD25 positive isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech). 1×106 CD4+CD25+ cells (>90% purity) were resuspended in 25ul PBS, and injected i.p. into 1-2 day old sf neonates. Mice were monitored for external signs of disease and killed after 25-60 days for analysis.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Cell isolation was performed as described21. For flow cytometry, cells were surface stained with the following directly conjugated antibodies specific for murine proteins: anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD62L (MEL-14), anti-CD44 (IM7), anti-CD45.1 (A20), anti-CD45.2 (104), anti-CD103 (2E7), anti-CD25 (PC61.5), anti-CD8 (53-6.7), anti CTLA-4 (UC10-4B9), anti-GITR (YGL-386), RatIgG2a (eBR2a) were from eBioscience, and anti-CXCR3 (220803), and anti-CCR6 (140706) were from R&D systems. To assess expression of functional P-selectin ligands, cells were first incubated with P- selectin-human IgM fusion proteins, followed by biotinylated goat-anti-human IgM (Jackson Immunoresearch) and streptavidin-PE (eBioscience). Data were acquired on FACsCalibur or LSRII flow cytometers (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar). For cell sorting experiments, CD4+ cells were enriched using Dynal CD4 T cell negative isolation kit (Invitrogen), stained for desired cell surface markers, and isolated using a FACS Vantage (BD Biosciences).

Intracellular staining

For intracellular staining of IFN-γIL-4, IL-17, Foxp3 and/or T-bet, lymphocytes were surface stained, then permeabilized with the eBioscience FixPerm buffer. Cells were then washed and stained with anti-IFN-γ (XMG1, eBioscience), anti-IL-4 (11B11, eBioscience), anti-IL-17 (TC11-18H10.1, Biolegend), anti-Foxp3 (FKJ-16s; eBioscience) and/or purified anti-T-bet (4B10; Santa Cruz Biotech) or mIgG1 isotype (P3, eBioscience) in staining media containing HBSS, 1%BSA, 10mM Hepes and 0.5% saponin for 30min. To detect T-bet, secondary staining was done with anti-mIgG1-APC or -PE (A85-1; BD Pharmingen). For BrdU incorporation, BrdU was continuously administered in drinking water at a concentration of 0.8mg/mL for 2 days before sacrifice. For intracellular Foxp3 and BrdU staining, a modified BrdU staining protocol was used. Lymphocytes were isolated and surface stained, followed by fixation in eBioscience FixPerm for 30 min. Cells were then stained for BrdU following the BrdU Flow Kit manufacturer’s instructions (BD Pharmingen).

In vitro suppression assay

Lymphocytes were isolated from the spleens of anti-CD40 treated Foxp3_gfp_ mice, enriched for CD4+ cells using a Dynal CD4 T cell-negative isolation kit (Invitrogen), and Foxp3+CXCR3+ cells were FACs sorted. CD4+CD25- effector lymphocytes were isolated from spleens and LNs of congenically marked B6.SJL mice using Dynal CD4 T cell-negative isolation kit. CD25- cells were isolated by staining with anti-CD25-PE followed by magnetic separation using anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). Final suspensions of CD4+CXCR3+GFP+ cells and CD4+CD25- cells were >95% pure. CD4+CD25- cells were incubated with 0.8μM carboxyfluorescein cuccinimidyl ester (CFSE) in PBS for 9 min in a 37°C water bath, washed with 100% bovine calf serum and resuspended in complete medium. In each culture well, CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25- T cells were incubated with T cell depleted, irradiated (2500 Rad) splenocytes with or without addition of sorted Treg cells. All stimulated cultures received 5μg/mL anti-CD3 (2C11) and 2μg/mL anti-CD28 (37.51). Proliferation of CD45.1+CD4+CD25- T cells during co-incubation with varying ratios of Treg cells was measured by assessing relative CFSE dilution after 110 hours of culture.

Chemotaxis assay

All recombinant murine chemokines were purchased from Peprotech. Red blood cell-depleted splenocytes isolated from WT, _Tbx21_-/- and _Cxcr3_-/- mice were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 in complete media for 1 h at 2×106/mL. Cells were then washed and resuspended at 10×106/mL and 1×106 cells were added to the top chamber of a 5-μM pore transwell (Costar). Chemokines were diluted in complete medium and added to the bottom of culture chambers to a final concentration of 100nM. Complete medium alone was added to the bottom of control chambers. Chemotaxis toward each chemokine or media control was measured in triplicate. After 90min of incubation at 37°C, 5%C02, 100μl was harvested from the bottom of each well and added to a fixed number of 15μm latex beads (Polysciences, Inc) to calculate the overall migration toward each chemokine or media. Replicate wells were then combined and stained for CD4 and Foxp3. The % specific migration was calculated by normalizing the frequency of migrated CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells to the input population.

In vitro T cell stimulation and cytokine analysis

6×106 red blood cell-depleted wild-type splenocytes were stimulated with 50ng/mL PMA and 1μg/mL ionomycin in the presence of 10μg/mL monensin in 1ml of complete media for 4 h at 37°C, 5%CO2. Following stimulation, cells were harvested, surface stained, permeabilized with eBioscience FixPerm and stained with antibodies against cytokines and transcription factors.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

Mice were infected with sonicated Mtb strain H37Rv using an aerosol infection chamber (Glas Col). A set of wild-type mice were sacrificed 1 day post infection to determine the infectious dose. In each experiment, 50-100 colony forming units (CFUs) were deposited in the lungs of each mouse.

Anti-CD40 and IL-2C administration

Mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p) with 25μg anti-CD40 (Clone IC10, eBioscience) or 25μg Rat IgG (Sigma) in PBS on days 0, 2, and 4. For IL-2C treatment, 50μg anti-IL-2 (JES6) was incubated with 1.5μg recombinant mouse IL-2 (carrier free, eBioscience) in PBS overnight at 4°C. Mice were injected with IL-2C i.p. on days 0 and 2. All mice were sacrificed on day 6. For competition experiments, cells were adoptively transferred via retro-orbital injection on day -1.

Quantitative PCR

RNA extraction was performed using Qiagen RNeasy columns (Qiagen) and cDNA was generated using Omniscript RT Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Presynthesized Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) were used to amplify Tbx21 (Mm00450960_m1), Il10 (Mm99999052_m1), Gzmb (Mm00442834_m1), and Tgfb1 (Mm01178820_m1) mRNA transcripts. Actb was used as an internal control with the sense primer TGACAGGATGCAGAAGGAGAT, anti-sense primer GCGCTCAGGAGGAGCAAT, and probe FAM-ACTGCTCTGGCTCCTAGCACCATTAMRA. Target gene values are expressed relative to Actb.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by unpaired student’s two-way repeated measures ANOVA, or two-tailed Student’s t test as indicated in figure legends.

References

- 1.Wilson CB, Rowell E, Sekimata M. Epigenetic control of T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nri2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiner SL. Development in motion: helper T cells at work. Cell. 2007;129:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szabo SJ, et al. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–669. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beima KM, et al. T-bet binding to newly identified target gene promoters is cell type-independent but results in variable context-dependent functional effects. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:11992–12000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of Foxp3 target genes in developing and mature regulatory T cells. Nature. 2007;445:936–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marson A, et al. Foxp3 occupancy and regulation of key target genes during T-cell stimulation. Nature. 2007;445:931–935. doi: 10.1038/nature05478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett CL, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wildin RS, et al. X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:18–20. doi: 10.1038/83707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jankovic D, et al. Conventional T-bet(+)Foxp3(-) Th1 cells are the major source of host-protective regulatory IL-10 during intracellular protozoan infection. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:273–283. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson CF, Oukka M, Kuchroo VJ, Sacks D. CD4(+)CD25(-)Foxp3(-) Th1 cells are the source of IL-10-mediated immune suppression in chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:285–297. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegmund K, et al. Migration matters: regulatory T-cell compartmentalization determines suppressive activity in vivo. Blood. 2005;106:3097–3104. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarween N, et al. CD4+CD25+ cells controlling a pathogenic CD4 response inhibit cytokine differentiation, CXCR-3 expression, and tissue invasion. J. Immunol. 2004;173:2942–2951. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belkaid Y. Regulatory T cells and infection: a dangerous necessity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:875–888. doi: 10.1038/nri2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott-Browne JP, et al. Expansion and function of Foxp3-expressing T regulatory cells during tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:2159–2169. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng Y, et al. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature07674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams LM, Rudensky AY. Maintenance of the Foxp3-dependent developmental program in mature regulatory T cells requires continued expression of Foxp3. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:277–284. doi: 10.1038/ni1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huehn J, et al. Developmental Stage, Phenotype, and Migration Distinguish Naive- and Effector/Memory-like CD4+ Regulatory T Cells. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:303–313. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sather BD, et al. Altering the distribution of Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells results in tissue-specific inflammatory disease. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1335–1347. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dudda JC, Perdue N, Bachtanian E, Campbell DJ. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells maintain immune homeostasis in the skin. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:1559–1565. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee I, et al. Recruitment of Foxp3+ T regulatory cells mediating allograft tolerance depends on the CCR4 chemokine receptor. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1037–1044. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suffia I, Reckling SK, Salay G, Belkaid Y. A role for CD103 in the retention of CD4+CD25+ Treg and control of Leishmania major infection. J. Immunol. 2005;174:5444–5455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan Q, et al. CCR4-dependent regulatory T cell function in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1327–1334. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubtsov YP, et al. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cole KE, et al. Interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (I-TAC): a novel non-ELR CXC chemokine with potent activity on activated T cells through selective high affinity binding to CXCR3. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:2009–2021. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farber JM. A macrophage mRNA selectively induced by gamma-interferon encodes a member of the platelet factor 4 family of cytokines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87:5238–5242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luster AD, Unkeless JC, Ravetch JV. Gamma-interferon transcriptionally regulates an early-response gene containing homology to platelet proteins. Nature. 1985;315:672–676. doi: 10.1038/315672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lord GM, et al. T-bet is required for optimal proinflammatory CD4+ T-cell trafficking. Blood. 2005;106:3432–3439. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferlin WG, et al. The induction of a protective response in Leishmania major-infected BALB/c mice with anti-CD40 mAb. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998;28:525–531. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<525::AID-IMMU525>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyman O, Kovar M, Rubinstein MP, Surh CD, Sprent J. Selective stimulation of T cell subsets with antibody-cytokine immune complexes. Science. 2006;311:1924–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.1122927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Afkarian M, et al. T-bet is a STAT1-induced regulator of IL-12R expression in naive CD4+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:549–557. doi: 10.1038/ni794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullen AC, et al. Role of T-bet in commitment of TH1 cells before IL-12-dependent selection. Science. 2001;292:1907–1910. doi: 10.1126/science.1059835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szabo SJ, et al. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-gamma production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 2002;295:338–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hancock WW, et al. Requirement of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 for acute allograft rejection. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1515–1520. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.10.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoneyama H, et al. Pivotal role of dendritic cell-derived CXCL10 in the retention of T helper cell 1 lymphocytes in secondary lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:1257–1266. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kursar M, et al. Cutting Edge: Regulatory T cells prevent efficient clearance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2661–2665. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou B, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin as a key initiator of allergic airway inflammation in mice. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/ni1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bettelli E, et al. Loss of T-bet, but not STAT1, prevents the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:79–87. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neurath MF, et al. The transcription factor T-bet regulates mucosal T cell activation in experimental colitis and Crohn’s disease. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:1129–1143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrett WS, et al. Communicable ulcerative colitis induced by T-bet deficiency in the innate immune system. Cell. 2007;131:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finotto S, et al. Asthmatic changes in mice lacking T-bet are mediated by IL 13. Int. Immunol. 2005;17:993–1007. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Godfrey VL, Wilkinson JE, Russell LB. X-linked lymphoreticular disease in the scurfy (sf) mutant mouse. Am. J. Pathol. 1991;138:1379–1387. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muller M, et al. CXCR3 signaling reduces the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by controlling the parenchymal distribution of effector and regulatory T cells in the central nervous system. J. Immunol. 2007;179:2774–2786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santodomingo-Garzon T, Han J, Le T, Yang Y, Swain MG. Natural killer T cells regulate the homing of chemokine CXC receptor 3-positive regulatory T cells to the liver in mice. Hepatology. 2008 doi: 10.1002/hep.22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Townsend MJ, et al. T-bet regulates the terminal maturation and homeostasis of NK and Valpha14i NKT cells. Immunity. 2004;20:477–494. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burchill MA, Yang J, Vogtenhuber C, Blazar BR, Farrar MA. IL-2 receptor beta-dependent STAT5 activation is required for the development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2007;178:280–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei G, et al. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ono M, et al. Foxp3 controls regulatory T-cell function by interacting with AML1 Runx1. Nature. 2007;446:685–689. doi: 10.1038/nature05673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1