Dynamic properties of the Sulfolobus CRISPR/Cas and CRISPR/Cmr systems when challenged with vector-borne viral and plasmid genes and protospacers (original) (raw)

Abstract

The adaptive immune CRISPR/Cas and CRISPR/Cmr systems of the crenarchaeal thermoacidophile Sulfolobus were challenged by a variety of viral and plasmid genes, and protospacers preceded by different dinucleotide motifs. The genes and protospacers were constructed to carry sequences matching individual spacers of CRISPR loci, and a range of mismatches were introduced. Constructs were cloned into vectors carrying pyrE/pyrF genes and transformed into uracil auxotrophic hosts derived from Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 or Sulfolobus islandicus REY15A. Most constructs, including those carrying different protospacer mismatches, yielded few viable transformants. These were shown to carry either partial deletions of CRISPR loci, covering a broad spectrum of sizes and including the matching spacer, or deletions of whole CRISPR/Cas modules. The deletions occurred independently of whether genes or protospacers were transcribed. For family I CRISPR loci, the presence of the protospacer CC motif was shown to be important for the occurrence of deletions. The results are consistent with a low level of random dynamic recombination occurring spontaneously, either inter-genomically or intra-genomically, at the repeat regions of Sulfolobus CRISPR loci. Moreover, the relatively high incidence of single-spacer deletions observed for S. islandicus suggests that an additional more directed mechanism operates in this organism.

Introduction

CRISPR adaptive immune systems of archaea and bacteria consist of clusters of identical repeats separated by unique spacer sequences of constant length adjoining a low complexity leader sequence carrying consensus sequence motifs, and physically linked to groups of cas genes (Jansen et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2002). Less frequently they are linked, at least functionally, with cassettes of cmr genes (Hale et al., 2009). They occur in the sequenced chromosomes of almost all archaea and about 40% of bacteria, as well as in some plasmids (reviewed in Lillestøl et al., 2006; Makarova et al., 2006; Grissa et al., 2008; Karginov and Hannon, 2010). The spacer regions constitute functionally active units which derive from extrachromosomal DNA of viruses and plasmids (Bolotin et al., 2005; Mojica et al., 2005; Pourcel et al., 2005; Lillestøl et al., 2006). For crenarchaea many spacers have been shown to match viral genomes or plasmids, despite the former often coexisting in a stable relationship with their hosts (Prangishvili et al., 2006a; Lillestøl et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2009). Whole CRISPR loci are transcribed from promoters within the leader regions and transcripts are then processed to yield smallest products in the range 35–45 nt containing most of the spacer sequence (Tang et al., 2002; 2005; Lillestøl et al., 2006; 2009; Brouns et al., 2008; Hale et al., 2009). Transcript processing is executed specifically within the repeat regions by Cas or Cmr proteins and the small crRNAs corresponding to the spacer and an adjoining part of the repeat are then transported to the invading genetic element (Brouns et al., 2008; Hale et al., 2008; 2009;). crRNAs, of different sizes, target either DNA (Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2008; Shah et al., 2009) or RNA (Hale et al., 2009) facilitated by groups of Cas and Cmr proteins respectively. Annealing of a crRNA–Cas protein complex to a complementary protospacer DNA sequence is presumed to facilitate inactivation, probably via degradation of the genetic element (Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2008; Shah et al., 2009).

Genome comparisons have indicated that new spacer-repeat units are inserted at the junction of the leader region and the first repeat for both archaea and bacteria (Pourcel et al., 2005; Lillestøl et al., 2006; 2009;) and this has been demonstrated experimentally for the bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus where a new spacer deriving from a phage genome was inserted into a CRISPR locus in response to phage infection, which in turn led to phage resistance (Barrangou et al., 2007). Moreover, it was demonstrated for this bacterium that perfectly matching spacer and protospacer sequences are essential to produce effective immunity via the CRISPR/Cas system (Barrangou et al., 2007; Deveau et al., 2008; Horvath et al., 2008). Thus, repeatedly invading genetic elements lead, potentially, to the addition of new spacer-repeat units at the leader end of a CRISPR locus and to a continual increase in its length. Many archaeal CRISPR loci carry 100 or more spacer-repeat units, but mechanisms exist to limit their sizes (Lillestøl et al., 2006). Although no direct evidence has been obtained for systematic fragmentation and subsequent loss of CRISPR loci fragments, a comparison of partially overlapping CRISPR loci of Sulfolobus solfataricus strains P2, P1 and 98/2 revealed that large indels, probably deletions, had occurred within some loci. Furthermore, two apparently inactive CRISPR loci E and F were found that were identical in sequence in strains P1 and P2, and the latter was deleted in strain 98/2, suggesting that loss or inactivation of linked Cas genes or mutation of the leader region had occurred (Lillestøl et al., 2006; 2009; Shah and Garrett, 2010).

Here we investigate the fidelity of crRNA–protospacer interactions for the CRISPR/Cas system of the crenarchaeal thermoacidophile Sulfolobus, and the stability of the CRISPR/Cas modules, when challenged by recently developed vector constructs (Deng et al., 2009) carrying viral or plasmid genes or protospacers, maintained under selection, which show varying degrees of sequence complementarity to host CRISPR spacers.

Results

Viral genes carrying spacer matches under selection can produce CRISPR loci deletions

Initial experiments were performed on the auxotrophic mutant S. solfataricus InF1, carrying an inactivated pyrF gene and using the expression vector pEXA2 modified from a Sulfolobus_–_Escherichia coli shuttle vector pZC1 (Peng et al., 2009) and containing an arabinose-inducible araS promoter (P1) as illustrated (Fig. 1). Three genes from the Acidianus two-tailed bicaudavirus (ATV) (Prangishvili et al., 2006b) were cloned into the multiple cloning site and were modified to generate perfect matches to single spacers in CRISPR loci A or D of S. solfataricus P2 (Fig. 2A). The genes correspond to: ATV618 encoding an AAA+ ATPase matching spacer 29 of CRISPR locus D; ATV145 encoding a putative DNA-binding protein matching spacer 28 of CRISPR locus D, and ATV892 encoding a Von Willebrand Factor A domain protein matching spacer 28 in CRISPR locus A. The protospacers of these viral genes showed perfect sequence matches to the CRISPR spacers and conserved CC or CT Protospacer Associated Motifs (PAM) located 5′ to the DNA strand, corresponding to the crRNA transcribed from spacers of family I and II CRISPR loci D and A, respectively, were also present (Lillestøl et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2009). Whereas the mRNAs of ATV618 and ATV892 carried protospacers complementary to crRNAs from the matching spacers, the crRNA matched the reverse transcript for ATV145.

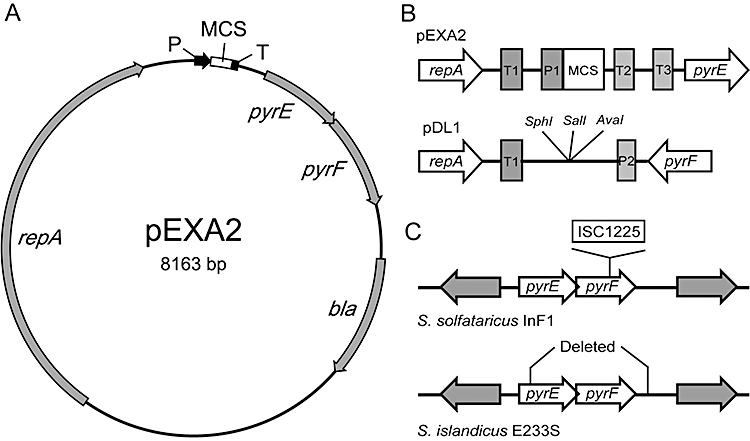

Fig. 1.

Scheme showing the vector–host constructs.

A. pEXA2 was produced by modifying the Sulfolobus_–_E. coli shuttle vector pZC1 (Peng et al., 2009).

B. The cloning region of the two vectors showing positions of promoters P1 and P2, where P1 is arabinose-inducible, the terminators T1 to T3, and cloning sites for viral genes and protospacers including a multiple cloning site (MCS) in pEXA2.

C. Mutations in the pyrE/pyrF genes of the uracil auxotrophic hosts S. solfataricus LnF1 (Z. Chen et al., unpublished) and S. islandicus E233S (Deng et al., 2009) are indicated.

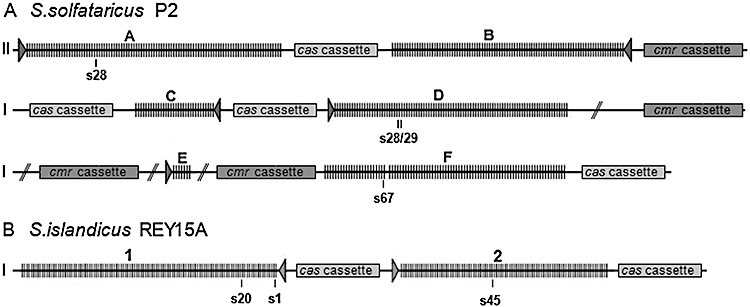

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of (A) the six CRISPR loci A to F of S. solfataricus P2 and (B) CRISPR loci 1 and 2 of S. islandicus REY15A, drawn to scale (extending from genomic positions 725 000 to 742 500), together with the cassettes of cas genes and cmr genes. CRISPR loci A to D (genomic positions 1 233 400–1 311 600) and CRISPR loci E and F (positions 1 744 000–1 815 500) are clustered within the S. solfataricus P2 genome. The positions of spacers matching protospacers within the vector constructs are indicated where ‘s’ denotes spacer followed by the number of the spacer measured from the leader region, indicated by an arrowhead. Sulfolobales family types of CRISPR/Cas modules are indicated by I and II.

ATV618 and ATV892 expression resulted in a slightly slower growth rate but after 50 generations mRNAs were still expressed and the vector was unchanged. ATV145 production led to slower cell growth, indicative of some toxicity, and little mRNA was expressed after 50 generations. Analysis of the vector revealed that mutations had occurred including an IS element insertion into the arabinose-regulatory site upstream from the promoter, thereby reducing transcription, and point mutations within the promoter and ORF but no mutations were observed in the protospacer or its adjacent PAM motif (data not shown).

Although transformation efficiencies could only be estimated approximately (see Experimental procedures), each construct yielded very few viable transformants. These were grown in liquid medium lacking uracil and the DNA was examined first by PCR for the presence and size of the CRISPR loci A or D which carried the matching spacer. The results revealed that most viable transformants carried a major deletion. Examples of PCR products derived from the deletion mutants are presented in Fig. 3A and all of the results are summarized in Table 1 where the estimated sizes of the deletions are given. For ATV618, the CRISPR/Cas modules A to D were absent while for ATV145, CRISPR/Cas modules A to D or C to D (Fig. 2) were absent from different transformants. In addition, large internal deletions, which included the matching spacer, were observed within CRISPR locus D for ATV145 and locus A for ATV892 (Fig. 3A; Table 1). We conclude that challenging the CRISPR systems with viral genes which are under selection, and carry perfectly matching protospacers with family-specific PAM motifs, yields primarily transformants carrying each specific spacer deletion which can grow under selection.

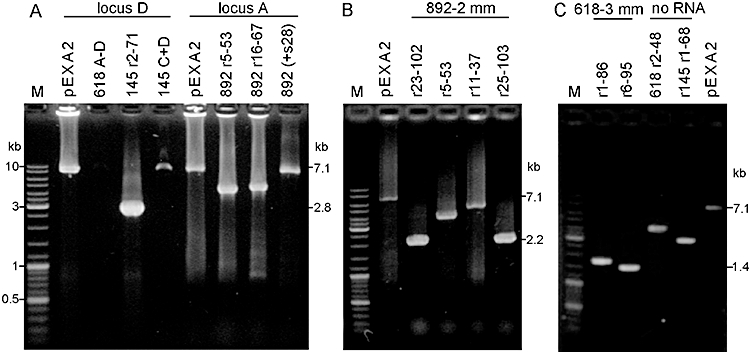

Fig. 3.

Agarose gels showing examples of PCR products obtained from CRISPR loci of transformants of S. solfataricus P2-InF1 carrying genes for ATV618, ATV145 and ATV892 cloned into pEXA2.

A. PCR products obtained from CRISPR loci after challenging with constructs carrying perfect matches to spacers in locus D (ATV618 and ATV145) and locus A (ATV892). The bracketed spacer number denotes the presence of the matching spacer 28.

B. PCR products amplified from locus A of transformants with ATV892 carrying two mismatches in the protospacer sequence.

C. PCR products from locus D when challenged by ATV618 containing three mismatches in the protospacer, and two samples showing perfect matching protospacers with no transcription.

M indicates DNA size markers. The illustrated PCR products yielded the results for estimating the deletion sizes marked with asterisks in Table 1.

Table 1.

Challenging the CRISPR systems of S. solfataricus P2 with modified bicaudavirus ATV gene inserts carrying matching protospacers and corresponding PAM motifs inserted into pEXA2 (Fig. 1).

| CRISPR loci deletions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATV gene insert | PAM motif | CRISPR locus/spacer | Transcript complementary to crRNA | Protospacer mismatches (position) | PCR estimate (kb) | Sequencing result |

| ATV618 | CC | D/29 | mRNA | 0 | > 90* | Loci A,B,C,D* |

| ATV618 | CC | D/29 | None | 0 | 3.3 | r5–r46 |

| 3.4* | r2–r48* | |||||

| ATV618 | CC | D/29 | mRNA | 1 (24) | > 90 (×2) | Loci A,B,C,D (×2) |

| > 30 | Loci C,D | |||||

| 1.5 | r10–r31 | |||||

| 0 (×2) | Spacer present (×2) | |||||

| ATV618 | CC | D/29 | mRNA | 2 (18, 24) | 0 (×2) | Spacer present (×2) |

| ATV618 | CC | D/29 | mRNA | 3 (18, 21, 24) | 5.4* | r1–r86* |

| 6.1* | r6–r95* | |||||

| ATV145 | CC | D/28 | Reverse | 0 | > 90 | Loci A,B,C,D |

| > 30* | Loci C,D* | |||||

| 4.4* | r2–r71* | |||||

| 3.5 | r6–r59 | |||||

| ATV145 | CC | D/28 | None | 0 | 4.4* | r1–r68* |

| 4.6 | r2–r73 | |||||

| ATV892 | TC | A/28 | mRNA | 0 | 3*(×2) | r5–r53*(×2) |

| 3.3* | r16–r67* | |||||

| 0* | Spacer present* | |||||

| ATV892 | TC | A/28 | mRNA | 2 (10, 19) | 4.9* | r23–r102* |

| 4.8* | r25–r103* | |||||

| 3.1* | r5–r53* | |||||

| 1.5* | r11–r37* | |||||

| pNOB8-315 | CG | F/67 | mRNA | 0 | 0 (×2) | Spacer present (×2) |

| pNOB8-315 | CC | F/67 | mRNA | 0 | 0 (×2) | Spacer present (×2) |

Northern blotting experiments were performed to test for the presence of crRNAs produced by the host cells. An example is shown (Fig. 4A) for cells transformed with the vector carrying the ATV618 gene which produced a large deletion, encompassing CRISPR loci A, B, C and D (Fig. 3A; Table 1). The total cellular RNA extract was probed with an oligonucleotide complementary to the crRNA of the matching spacer 29 of locus D (Fig. 2). In the presence or absence of arabinose, no crRNA was detected for spacer 29 of transformant samples harvested at different times, whereas a typical range of processed products, including the smallest crRNAs (Lillestøl et al., 2006; 2009;), were observed in the control sample carrying empty pEXA2 (Fig. 4A).

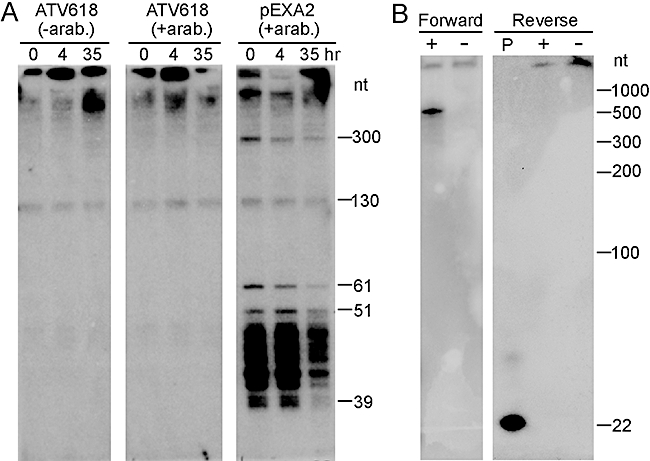

Fig. 4.

A. Northern blot probing for crRNAs transcribed from spacer 29 of locus D of S. solfataricus P2. The transformant which apparently lacks CRISPR loci A to D (Table 1) was probed. The vector construct carried the ATV618 gene with a matching protospacer and CC motif. Samples were tested without and with arabinose stimulation of ATV618 mRNA transcription to test whether there was any effect of the mRNA. pEXA2 denotes transformants carrying the empty vector with no insert. Normally processed crRNAs are only visible for transformants carrying the empty vector.

B. Northern blot probing for the protospacer region of ATV145 transcripts from forward and reverse strands. + denotes the total RNA isolated from the pEXA2-ATV145 transformant and − indicates the total RNA isolated from the transformant of the construct pEXA2-ATV145 for which the araS promoter had been exchanged with an archaeal transcriptional terminator (see main text). ‘P’ represents a positive control where a 10 pmol 22-nt-long DNA oligonucleotide is employed that is complementary to the probe. Sequences of oligonucleotide probes are given in Experimental procedures.

The effects of ATV618 gene inserts carrying single-, double- and triple-spacer mismatches were also examined and vector constructs were made with base-pair changes within the protospacer region of the gene as indicated (Table 2). For one, two or three base-pair mismatches again a low number of viable transformants was obtained and they were analysed for deletions in the CRISPR loci. For the single mismatch, six transformants were analysed four of which showed major deletions (Table 1). Two lacked the region carrying CRISPR/Cas modules A to D, another lacked modules C and D, and a fourth carried a large internal deletion in locus D (r10 to r31) including matching spacer 29. No changes in CRISPR locus D were detected for the remaining two transformants (Table 1). The construct with two mismatches yielded only two transformants which produced PCR products of unaltered size from locus D each with an intact spacer 29 and the host genome changes were not identified. In a parallel experiment with two mismatches introduced into the ATV892 protospacer (Table 2), four transformants were obtained. PCR products obtained across the deletions, illustrated in Fig. 3B, were analysed and for each one large deletions within locus A were identified (Table 1). Three mismatches in the ATV618 protospacer yielded two transformants showing different large deletions (r1–r86, r6–r95) including spacer 29 (Fig. 3C; Table 1).

Table 2.

DNA strands of cloned protospacers showing the sequence corresponding to crRNAs.

| Construct | Locus/spacer | Sequence | Mismatches | Positions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) S. solfataricus P2 | ||||

| ATV618 | D/29 | CCATTTTGATAACTAGATGTGGAACCGAAGTTTACTACTAGTT | 0 | |

| D/29 | CCATTTTGATAACTAGATGTGGAACCAAAGTTTACTACTAGTT | 1 | 24 | |

| D/29 | CCATTTTGATAACTAGATGTAGAACCAAAGTTTACTACTAGTT | 2 | 18, 24 | |

| D/29 | CCATTTTGATAACTAGATGTAGAGCCAAAGTTTACTACTAGTT | 3 | 18, 21, 24 | |

| ATV892 | A/28 | TCCCTCGCTAACGTTCAAATCTTTCAATAATTTTTGCACGT | 0 | |

| A/28 | TCCCTCGCTAACATTCAAATCCTTCAATAATTTTTGCACGT | 2 | 10, 19 | |

| ATV145 | D/28 | CCGAAAAGCCAATCCCAAGATACATCATCGCAGAAATATTCA | 0 | |

| Protospacer | A/28 | TCCCTCGCTAACGTTCAAATCTTTCAATAATTTTTGCACGT | 0 | |

| A/28 | TCCTTCGCTAACGTTCAAATCTTTCAATAATTTTTGCACGT | 1 | 1 | |

| A/28 | TCCCTCGCTAACGTTCAAATCCTTCAATAATTTTTGCACGT | 1 | 19 | |

| A/28 | TCCCTCGCTAACGTTCAAATCTTTCAATAATTTTTGCACGC | 1 | 38 | |

| A/28 | TCCTTCGCTAACGTTCAAATCTTTCAATAATTTTTGCACGC | 2 | 1, 38 | |

| A/28 | TCCCTCGCTAACGTTCAAATCTTTCAATAATTTTTGCGGCC | 4 | 35–38 | |

| A/28 | TCCCTCGCTAACGTTCAAATCTTTCAATAATCGGCCGCACA | 10 | 29–38 | |

| (B) S. islandicus REY15A | ||||

| Protospacer | 2/45 | CCATTAGGAGTCGTAGCACAGGGAGCTGTACAGTCACAGAA | 0 | |

| 2/45 | CCACTAGGAGTCGTAGCACAGGGAGCTGTACAGTCACAGAA | 1 | 1 | |

| 2/45 | CCATTAGGAGTCGTAGCACAGAGAGCTGTACAGTCACAGAA | 1 | 19 | |

| 2/45 | CCATTAGGAGTCGTAGCACAGGGAGCTGTACAGTCACAGAG | 1 | 38 | |

| 2/45 | CCATTAGGAGTCGTAGCACAGGGAGCTGTACAGTCAGTCGA | 4 | 34–37 | |

| 2/45 | CCATTAGGAGTCGTAGCACAGGGAGCTGTACGTCGACCTGC | 8 | 29–32, 35–38 |

CRISPR loci deletions are not dependent on protospacer transcription

Each of the above changes observed in the CRISPR loci will prevent both the CRISPR/Cas and CRISPR/Cmr systems from targeting the cloned viral genes or their transcripts respectively (Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2008; Hale et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2009). In order to inhibit transcription and remove the possibility of viral gene transcripts feeding back onto the CRISPR loci and inducing spacer deletions, vectors were constructed for the genes of ATV145 and ATV618 where no transcription occurred. Promoter regions were replaced by an elongated archaeal T-rich terminator region (see Experimental procedures). For both these constructs, again transformation efficiency was very low and two transformants were analysed from each construct. For the ATV145 construct, CRISPR locus D deletions of 4.4 and 4.6 kb were estimated from PCR reactions (Fig. 3C) and for the ATV618 constructs, CRISPR locus D deletions of 3.3 and 3.4 kb were detected. Subsequent sequencing showed that all four lacked matching spacers 28 or 29 respectively (Table 1). For ATV145, the crRNA is complementary to the reverse transcript and it was established by Northern blottings that there was no transcription on either strand across the protospacer (Fig. 4B). For ATV618, where the crRNA is complementary to the mRNA, using the same vector construct, no transcription was observed in Northern blots (data not shown). This result eliminates the possibility that the deletions occurring within the CRISPR loci resulted from a feedback mechanism involving transcripts from either strand of the gene.

Some CRISPR/Cas modules may be inactive

CRISPR locus F has been shown, exceptionally, to be identical in sequence between S. solfataricus strains P1 and P2, and to lack a leader region and some cas genes (Lillestøl et al., 2006; 2009;). This suggested that its capacity to add new spacers had been impaired. Therefore, we investigated whether CRISPR locus F was affected by vector-borne matching protospacers. Spacer 67 of CRISPR locus F (Fig. 2) matches imperfectly (three mismatches) the gene of a putative partitioning protein NOB8-315 encoded by the Sulfolobus conjugative plasmid pNOB8 (She et al., 1998). The gene with three mismatches was inserted into pEXA2 cloning site in addition to a mutated gene with a perfect match. Constructs were also prepared with and without the family I CC PAM motif but each construct produced transformation efficiencies similar to the empty vector [on average 104 cfu (µg DNA)−1] and no deletions of spacer 67 were detected in the sequenced PCR products (Table 1). Therefore, we infer that cluster F is inactive and this is compatible with the observation that the RNA transcript from cluster F is incompletely processed such that the active crRNA components, in the size range 35–45 nt, are not formed (Fig. S1).

Protospacers carrying mismatches also affect CRISPR loci in Sulfolobus islandicus REY15A and S. solfataricus P2

Given that the CRISPR loci changes were observed independently of whether viral genes carrying matching protospacers were transcribed, we inferred that it was sufficient to perform further experiments with vector-cloned protospacer DNAs carrying appropriate PAM motifs (Lillestøl et al., 2009). Moreover, since a reliable and stable genetic system has recently been developed for Sulfolobus islandicus REY15A (Deng et al., 2009), which also carries a much simpler CRISPR/Cas system with only a tandem pair of CRISPR loci 1 and 2 (and two cmr cassettes) (Fig. 2B), we performed a series of parallel experiments in which we synthesized and cloned protospacers matching to selected CRISPR spacers, or combinations of spacers, for both S. solfataricus P2 and S. islandicus REY15A (Fig. 2).

Several vector constructs were prepared each carrying a protospacer showing increasing degrees of sequence mismatches (listed in Table 2) to spacer 45 of family I CRISPR locus 2 of S. islandicus REY15A and to spacer 28 of family II CRISPR locus A of S. solfataricus P2 (Fig. 2) and the constructs carried the protospacer PAM motifs CC for the former and CT for the latter (Table 2). Both spacers were 38 bp in length and constructs were prepared with perfect matches, one mismatch at spacer positions 1, 19 or 38, two mismatches exclusively for S. solfataricus at positions 1 and 38, and additional constructs were made with four mismatches (positions 34–38) and 8 or 10 mismatches (positions 29–38) all at or near the 3′ end (Table 2). For each construct, including the 8–10 mismatches at the 3′ end, low transformational efficiencies were observed compared with the empty vector (Table 3). Furthermore, for all except the latter constructs, some deletions were observed within CRISPR loci covering the matching spacer (Table 2).

Table 3.

Deletions observed in CRISPR locus 2 of S. islandicus REY15A and locus A of S. solfataricus P2.

| Deletions in S. islandicus CRISPR locus 2 | Deletions or insertions in S. solfataricus CRISPR locus A | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Mismatches in protospacer 45 or 28 (38 bp) | PCR estimate (kb) | Sequencing result | PCR estimate (kb) | Sequencing result |

| P1 | 0 | 64 bp** | r45–r46 (×3) | 4.5 | r24–r93 |

| 3.7 (×2) | n.d. | 3.8* | r7–r64 | ||

| 2.7* | r3–r47 | 6.4* | r2–r103 | ||

| 2.5 (×2) | n.d. | 0 (×2) | n.d. (×2) | ||

| 2.2 | r40–r69 | ||||

| 1.7 (×2)** | r30–r53 | ||||

| r22–r47 | |||||

| 0.5 | r38–r52 | ||||

| 0 (×5) | n.d. (×5) | ||||

| P2 | 1 (+1) | 4.7 | n.d. | +1, 6.4 | n.d. |

| 0 | n.d. | +1 | ISC1359 in sp28 | ||

| 0, 4.4 | n.d. | ||||

| 6 | n.d. | ||||

| P3 | 1 (+19) | 64 bp | r45–r46 | 3* | r5–r56 |

| 4.2 | n.d. | 1 | r18–r30 | ||

| 0 | n.d. | +1 | ISC1359 in sp28 | ||

| 0* (×2) | n.d. (×2) | ||||

| P4 | 1 (+38) | 64 bp | r45–r46 | 0 | Spacer present |

| 0 | n.d. | +1 | ISC1359 in sp28 (×2) | ||

| P5 | 2 (+1, +38) | n.d. | n.d. | 5.3* | n.d. |

| 4.8* | r26–r103 | ||||

| 0 (×2) | n.d. | ||||

| +1 | n.d. | ||||

| P6 | 5 (+34−38) | 3.4 | n.d. | 2* (×3) | r5–r52 |

| 1.7 | n.d. | 1* | r5–r52 | ||

| 0 (×2) | n.d. (×2) | 2 | r23–r41 | ||

| 0 | n.d. (×1) | ||||

| P7 | 8–10 (+29−38) | 0 (×9) | Spacer present (×1) | 0* (×5) | Spacer present (×1) |

PCR products across the deleted regions of locus 2 of S. islandicus are shown in Fig. 5A for transformants arising from the perfectly matching protospacers, with control PCR reactions provided for locus 1 showing no changes except for sample 8 where both CRISPR loci had been deleted. These PCR products are indicated in a summary of all the results listed for S. islandicus in Table 3. Similarly, for the S. solfataricus constructs, examples of PCR products from constructs carrying both perfectly matching, and mismatching, protospacers are given in Fig. 5B, including an example, in sample P3, of an ISC1359 insertion. All the results are summarized in Table 3.

Fig. 5.

Agarose gels showing examples of PCR products obtained from CRISPR loci of transformants carrying protospacers and CC and CT PAM motifs cloned into pDL1 and pEXA2 respectively.

A. S. islandicus REY15A where both locus 2 carrying the matching spacer and, as a control, locus 1 were amplified.

B. S. solfataricus P2. P1 to P7 refer to the experiments listed in Table 3.

M indicates DNA size markers. Bracketed spacer numbers denote the presence of the matching spacer. All the illustrated samples carrying deletions are marked with asterisks in Table 3.

In a control experiment to confirm that the PCR products reflected the predicted and predominant genomic changes, and not some minor smaller products, Southern blot experiments were performed on the S. islandicus CRISPR loci. Results for five of the transformants in Fig. 5A which produced major genomic changes (samples 2, 3, 4, 6 and 9) were tested. The results presented in Fig. 6A all show fragment sizes that are consistent with the sizes of the PCR reactions (Fig. 5A; Table 3)

Fig. 6.

Southern blot analysis of CRISPR locus deletions of S. islandicus REY15A transformants where sample C denotes a control sample of S. islandicus REY15A. The deleted regions determined by sequencing are indicated above each well.

A. Analysis of deletions in locus 2 determined from the PCR products shown Fig. 5A where the numbers in the brackets correspond to the sample numbers on agarose gel.

B. Samples correspond to the PCR products illustrated in Fig. 7A and B. Tracks 1 and 2 carry transformants 1 and 2 while tracks 3 and 4 carry transformants with protospacers matching both spacer 20 of locus 1 and spacer 45 of locus 2 (Table 5).

The lower diagram shows the restriction sites in the CRISPR region where the expected DNA fragment sizes are indicated.

There was an important difference between the two sets of results. Whereas changes in the CRISPR locus 2 of S. islandicus exclusively involved deletions, insertions of the transposable element ISC1359 were observed within matching spacer 28 for some of the S. solfataricus transformants, after its target site ACGT (Redder and Garrett, 2006) (Table 3; Fig. 5B). This result is consistent with the relatively high transpositional activity found only in the latter strain (Martusewitsch et al., 2000; Redder and Garrett, 2006; Deng et al., 2009).

Testing for the significance of the family I CC PAM motif

A CC PAM motif was predicted to be important for family I crRNA targeting in Sulfolobus species, with a low tolerance for a T at either position (Lillestøl et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2009). Therefore, using the S. islandicus genetic system, we prepared a series of constructs with protospacers matching spacer 45 of CRISPR locus 2 (Fig. 2) with variants of the CC motif. High transformation levels (see Experimental procedures) were observed with motifs GG, GA and TT, and there was no evidence of deletions in CRISPR loci among the transformants examined (Table 4). The results obtained with CT and TC were less clear. The former yielded relatively high transformation efficiency but produced a single large deletion including the matching spacer, for one of six transformants examined, while the TC motif produced few transformants but no evidence of deletions in the four transformants examined. Only CC yielded low transformation efficiencies and high levels of deletions, for 12 of the 17 transformants examined (Table 3). These experimental results confirm that the predicted CC PAM motif is required for targeting foreign DNA in vivo for the family I CRISPR/Cas system of Sulfolobus (Lillestøl et al., 2009) thereby facilitating the distinction of foreign protospacer sequences from host CRISPR spacer sequences which carry the equivalent motif AA in their repeat.

Table 4.

Challenging the CRISPR/Cas system of S. islandicus REY15A (family I) with a protospacer perfectly matching to spacer 45 of CRISPR locus 2, employing alternative dinucleotide PAM motifs.

| Deletions in S. islandicus CRISPR locus 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Locus/spacer + PAM motif | Transformation efficiency [cfu (µg DNA)−1] | PCR estimate (kb) | Sequencing result |

| None | 5.2 × 105 | 0 (×2) | Spacer present (×1) |

| L2/45 + GG | 4.1 × 105 | 0 (×2) | Spacer present (×2) |

| L2/45 + GA | 6.3 × 104 | 0 (×2) | Spacer present (×2) |

| L2/45 + CC | 1.7 × 102 | See P1, Table 3 | See P1, Table 3 |

| L2/45 + CT | 2.9 × 103 | 6 | r11–r91 |

| 0 (×5) | Spacer present (×1) | ||

| L2/45 + TC | 94 | 0 (×4) | Spacer present (×2) |

| L2/45 + TT | 7 × 104 | 0 (×3) | Spacer present (×3) |

Mechanism of formation of deletions within CRISPR loci – spontaneous or induced?

The large variety of CRISPR loci deletion mutants produced in these experiments raised the question as to whether they resulted from a low level of spontaneous intracellular recombination or whether the effects are somehow induced. In order to examine this further we performed two additional experiments in the S. islandicus system. In the first, a construct was generated carrying two protospacer sequences, matching spacer 20 in CRISPR locus 1 and spacer 45 in CRISPR locus 2 (Fig. 2B), each with an associated CC PAM motif. It was inferred that simultaneous and independent loss of both spacers would be a highly improbable event. Of the very few transformants obtained none generated PCR products from CRISPR loci 1 or 2, suggesting that both were absent (Table 5). This was then confirmed by a Southern blot analysis which demonstrated that both CRISPR/Cas modules 1 and 2 had been deleted. There was no evidence for independent deletions having occurred in the two CRISPR loci (samples 3 and 4 in Fig. 6B).

Table 5.

Characterization of the CRISPR loci of S. islandicus REY15A (family I) after challenging with constructs carrying protospacers matching spacers within locus 1 and/or 2 (Fig. 2).

| CRISPR locus deletion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | CRISPR locus/spacer (+CC motif) | Transformation efficiency [cfu (µg DNA)−1] | PCR estimate (kb) | Sequencing result |

| 1 | L2/45 + L1/20 | 4 | > 17 kb (3×) | L1 + L2 (×2) |

| 2 | L1/1 | 6 | 64 bp (2×) | r1–r2 (×2) |

| 0.2 and 5 | Leader–r3 and r1–r80 |

In the second experiment a protospacer matching spacer 1 of CRISPR locus 1 was tested. This has a very low probability of being randomly deleted since deletion as a result of recombination can only occur via repeat 1 adjacent to the leader region. Only three transformants were obtained in the experiment, two of which had specifically lost spacer 1 and a flanking repeat (r1 to r2), and a third that showed a mixture of two types of deletion, one from r1 to r80, the other from within the leader region to r3, both including spacer 1 (Fig. 7A and B; Table 5). Deletion mutants r1–r2 and r1–r80 were examined further by a Southern blot analysis and the sizes of the restriction fragments (samples 1 and 2 in Fig. 6B) correlate with those of the PCR reactions except that only the larger deletion product was detectable for sample 2 (5.5 kb) consistent with it being the dominant deletion in the transformant (Figs 6B and 7).

Fig. 7.

PCR products showing deletions in CRISPR locus 1 produced by a protospacer matching spacer 1 of locus 1 (Table 5).A. PCR from three transformants using the primers bordering spacer 1 of locus 1 where C denotes a control sample run with S. islandicus REY15A.

B. PCR products obtained from the same transformants (1–3) with primers amplifying the whole of locus 1.

Next, we investigated whether we could find any experimental evidence for deletions occurring in CRISPR loci of the untransformed S. solfataricus P2. PCR products were generated from within CRISPR loci A and D, and a continuum of minor bands were observed, all smaller than the main expected product (Fig. S2). The yields of the smaller products were enhanced by using shorter elongation times in the PCR reactions and a limited size range of these products were cloned and sequenced as indicated, for loci A and D, and the results showed that they carried a range of CRISPR locus deletions with perfectly maintained repeat–spacer junctions (Fig. S2). This indicates that a low level of random CRISPR loci deletion variants is produced during amplification. Moreover, the presence of perfectly maintained repeat–spacer boundaries in all the sequenced variants (Fig. S2) suggests that deletions occur as a result of homologous recombination between the repeats.

This last result has important implications for how the CRISPR loci deletions are generated in vivo (see Discussion) but they also helped to resolve a major practical problem that recurred throughout this study. For the experiments summarized in Table 3, PCR products from about 80 individual transformants were sequenced for each Sulfolobus strain. Despite the appearance of strong homogeneous PCR products, carrying deletions, on agarose gels, about 30 products for each strain yielded mixed sequence traces (which include the samples indicated by n.d. in Fig. 5). We infer the latter were caused by sequence heterogeneity generated by recombination resulting in the random loss of a few spacers during the PCR reactions. Many of these PCR products were subsequently cloned and resequenced successfully.

Discussion

The experiments mimic, to a degree, the chronic invasion of Sulfolobus cells by viruses, conjugative plasmids or other aggressive genetic elements. They differ in that when the protospacer-carrying vectors are targeted and degraded by the host CRISPR immune systems this should lead to cell death due to lack of uracil synthesis. The survival of very few transformants, for most of the constructs tested which carried perfectly or closely matching protospacers, confirms that the majority of cells do indeed die. Moreover, most, but not all of the cultured transformants survived as a result of either deletions occurring within the chromosomal CRISPR locus, including the matching spacer, or as a result of deletion of whole CRISPR/Cas modules.

The mechanism by which deletions occur within CRISPR loci is puzzling, and this is reinforced by a summary of the sequencing data for CRISPR locus A of S. solfataricus and locus 2 of S. islandicus (Tables 1 and 3) and in histograms (Fig. 8). The numerous sequenced deletion variants reveal a wide range of deletion sizes with very few being identical. Moreover, although the two distributions are qualitatively similar with broad distributions peaking at the matching spacer, there are significant differences. On average, the deletions in S. solfataricus are larger and in S. islandicus, there is a high incidence of specific deletions of single matching spacers (and an adjacent repeat) that are not observed for S. solfataricus (Fig. 8A and B). The latter effect was also reinforced by the results of the experiment (Fig. 7; Table 5) where two of the three analysed S. islandicus transformants had specifically lost the matching spacer 1 of CRISPR locus 1. Not included in the histograms is the selective targeting of the matching spacer by ISC1359 in S. solfataricus (Table 3; Fig. 5B).

Fig. 8.

Distributions of deletions within CRISPR loci produced by constructs carrying (A) ATV viral genes or protospacer sequences matching spacer 28 of CRISPR locus A of S. solfataricus P2 and (B) protospacer sequences matching spacer 45 of CRISPR locus 2 of S. islandicus REY15A.

The data for both Sulfolobus species (Fig. 8), and the results for the experiments targeting spacer 1 of CRISPR loci 1 in S. islandicus (Table 5), are compatible with the occurrence of a low level of spontaneous recombination activity occurring within CRISPR loci, intracellularly, either during replication or during the G2 phase of the cell cycle when two chromosomal copies are present per cell for longer periods (Bernander, 2007). This could result in the formation of viable transformants carrying vector-borne protospacers in cells that have undergone deletion of matching CRISPR spacers. This hypothesis is also consistent with the low level of random recombination events occurring between repeats observed during PCR reactions performed on whole, and different, CRISPR loci (Fig. S2). It is also supported by the amplification of two distinct deletion products from the same transformant as shown for two of the four P2 samples in Table 3, and also for the samples 1 in Fig. 7A and B where deletions of 0.2 kb and 5 kb were observed for one transformant albeit with the larger product dominating (Table 5; Fig. 6B).

This suggests that recombination can occur intracellularly during colony development or culturing. However, the data for S. islandicus (Fig. 8B) indicate that there may be an alternative mechanism operating, given the frequency of specific spacer deletions that are observed (50% in Fig. 8B). It raises the possibility that the spacer deletions are somehow induced in S. islandicus either by the matching vector-borne protospacer within the construct, or by the host itself, since we have eliminated the possibility experimentally that transcripts carrying the protospacer sequence could have a feedback role (Table 1; Fig. 3C). There remains the possibility that a very low level of crRNA feedback and targeting of the matching chromosomal spacer can occur. Subsequent recombination at the repeats bordering the cut spacer might then be the most effective mechanism for chromosomal repair.

The operation of the spontaneous but precise repeat-based recombination mechanism could also explain how the CRISPR loci can change relatively quickly in natural environments including the multiple indels, probably deletions, observed in the large corresponding CRISPR loci of three sequenced S. solfataricus strains P1, P2 and 98/2 (Lillestøl et al., 2006; 2009; Shah and Garrett, 2010), but also the more extreme case of the complete lack of shared CRISPR loci spacer regions in sequences of several very closely related S. islandicus strains isolated from a few localized geographical locations (Held and Whitaker, 2009; Shah et al., 2009; L. Guo et al., submitted).

Clearly, Sulfolobus cells adapt to being challenged by protospacers that match spacers in their active CRISPR loci primarily by losing the matching spacer. However, a significant proportion of the viable transformants (about 20%) retained their perfectly matching spacers to ATV genes (Table 1). Moreover, searching for evidence of mutations in the cas gene cassettes or leader regions including the CRISPR loci promoters of a few of the viable S. islandicus transformants failed to reveal any changes, although such defects which occur naturally in the cas gene cassettes and leader region appear to explain the inactivity of CRISPR locus F of S. solfataricus (Table 1) (Lillestøl et al., 2009). This implies that there has to be a mechanism, in trans, for shutting down CRISPR transcription and/or processing, possibly involving the post-translational modification of a Cas protein. A possible effector could also be the Sulfolobus repeat-binding protein (Peng et al., 2003) which can alter transcription from CRISPR loci (L. Deng, unpublished) but there may be other silencing systems including inhibiting the CRISPR locus promoter within the leader region, as have been observed in a bacterium (Pul et al., 2010). We plan to sequence one or more genomes of the S. islandicus transformants in an attempt to gain more insight into this process.

Finally, the results serve to emphasize further the diversity of the CRISPR/Cas and CRISPR/Cmr systems, and the differences occurring between, and among, archaeal and bacterial systems. Thus, the target discrimination mechanism of the crRNA–Cas protein complex differs from that of the bacterium Staphylococcus epidermidis which specifically targets complementary protospacers on foreign DNA when any sequence mismatches occur between the short repeat sequence at the 5′ end of the crRNA (Marraffini and Sontheimer, 2010). Here we show that matching to the Sulfolobus family I CC PAM motif is important for crRNA to target foreign DNA, with other mismatching motifs GA, GG and TT having no effect. Moreover, whereas the S. thermophilus CRISPR/Cas apparatus requires perfectly matching spacer–protospacer sequences to be activated (Barrangou et al., 2007), the Sulfolobus system appears to be much less stringent. One possible explanation to reconcile all these differences is that the PAM motif interaction compensates for the imperfect annealing of crRNA to the protospacer in the Sulfolobus systems. This apparent flexibility of the targeting mechanism may also reflect the much wider variety and diversity of viruses and plasmids which inhabit these hyperthermophilic crenarchaea (Prangishvili et al., 2006a).

Experimental procedures

Growth of Sulfolobus cells and general DNA manipulations

All Sulfolobus cells were grown at 75–78°C in complex medium TYS or selection medium SCV and competent cells were prepared and transformed as described (Deng et al., 2009). Arabinose was added to media to a final concentration of 0.2% to activate the araS promoter (the promoter for the arabinose-binding protein) of pEXA2 (Deng et al., 2009).

Standard methods of cloning and other DNA manipulations were used (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). DNA restriction and modification enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Hitchin, UK) or Fermentas (St. Leon-Rot, Germany), Ex Taq DNA polymerase was purchased from Takara (Otsu, Japan) and Pfu polymerase was obtained from Fermentas (St. Leon-Rot, Germany). Total DNA was isolated using DNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Westberg, Germany). Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli or Sulfolobus cells using QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen Westberg, Germany) or NucleoSpin Plasmid Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). PCR products were purified by QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Westberg, Germany). All primers were synthesized by TAG Copenhagen A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark). DNA size marker used were: O'GeneRuler™ DNA Ladder Mix, 100–10 000 bp and FastRuler™ DNA Ladder, 50–1500 bp (Fermentas).

Strains and vector construction

The S. solfataricus P2 vector host S. solfataricus P2-InF1 carried a pyrF gene inactivated by a single copy of ISC1225 and the S. solfataricus vector carried Sulfolobus acidocaldarius pyrE/F genes. For S. islandicus, the double-deletion mutant S. islandicus E233S was used, which carried a large pyrEF gene deletion and a complete lacS gene deletion (Deng et al., 2009).

pDL1 was constructed by self-ligation of the PvuII- and ZraI_-_digested pZC1 large fragment (Peng et al., 2009). pEXA was produced by the triple ligation of products of: SphI- and AvaI-digested pDL1; SphI- and NdeI-digested araS promoter fragment, and NdeI- and SphI-digested multiple cloning site (MCS) fragment. The araS promoter fragment was amplified by primer araSF (5′-gcGCATGCTTTTTTTTAGAAAAACATCCAATATGTTAAC-3′) and araSR (5′-ttttttttCATATGCTCGGGTACTTTTATGACCTAAC-3′) using total S. solfataricus P2 DNA as template (underlined nucleotides indicate restriction digestion sites and small letters constitute protection nucleotides for restriction sites).

The MCS fragment was synthesized by primers MCS1, MCS2, MCS3, MCS4, MCS5 and MCS6 (MCS1-5′ ttttttttCATATGCATCATCACCATCATCATAGTAGTGGTTTAGT; MCS2-5′CATCGATTCGCGATCCCCTTGGTACTAAACCACTACTATGATGATGGTGA; MCS3-5′AAGGGGATCGCGAATCGATGCTAGCTACGCGTCTCCGGATGTACAAAGGC; MCS4-5′ATCAGCGTCGACCTTATCGTCATCATCAGGCCTTTGTACATCCGGAGACG; MCS5-5′GACGATAAGGTCGACGCTGATCAAGCGGCCGCACACCATCATCATCACCA; MCS6-5′aaCCCGGGAAAAAAAAGATTTTGCTTAGTGGTGATGATGATGGTGTGCG) as follows: all primers were added to the final concentration of 0.2 µM in a standard 50 µl PCR reaction: 94°C for 20 s, 65°C for 20 s and 72°C for 20 s over 15 cycles. One microlitre of the product was then added as DNA template to a standard PCR reaction using MCS1 and MCS6 as primers. After 20 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 65°C for 20 s and 72°C for 20 s, the MCS fragment was synthesized.

To construct protospacer-containing vectors, SOE-PCR was performed to generate protospacer fragments. Briefly, primers were designed with about 18 nt overlap at their 3′ ends and were added to a standard PCR reaction, run at 95°C for 3 min, 30 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 40°C for 15 s and 68°C for 5 s. The product was then purified by a Nucleotide removal kit (Qiagen, Westburg, Germany), digested overnight and repurified using this kit. Ligation was performed by T4 ligase with the corresponding digested vector at 22°C for 1 h. The ligation product was transformed into E. coli DH5α directly by heat shock following a standard protocol (Sambrook and Russell, 2001) and transformants were screened by colony PCR and verified by sequencing.

For S. solfataricus experiments, the S. solfataricus pyrEF genes in pEXA were replaced by pyrEF genes from S. acidocaldarius to minimize the possibility of homologous recombination. The pEXA vector was fully digested with Cfr91, destroying one of three KpnI sites on the vector and then partially digested with KpnI to remove the pyrEF genes and the cut vector was purified with a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). The S. acidocaldarius pyrEF genes were amplified with primers S.aci1: 5′-tcccCCCGGGAGAAAAAAAAGCTATGGATATTGTCTTACCAC-3′ and S.aci2: 5′-cgg GGTACCagaaaaaaaatctgttgtgggaacttcac-3′, purified and cut with Cfr91 and KpnI and then inserted into the linear pEXA to produce pEXA2. Bold nucleotides represent mismatches to the genomic sequence to enable transcriptional terminators to be inserted into the vector on both sides of the pyrEF genes. The integrity of the whole construct was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

To remove the araS promoter from pEXA2, the plasmid was digested with SphI and NdeI. To inhibit transcription, a terminator sequence was generated using the primer set Term/SphI: 5′-acatGCATGCTTCTTTTTCTTTCCCTTCTTTTTTTACC-3′ and Term/NdeI: 5′-ggaattcCATATGAAAAAGAGGTAAAAAAAGAAGGG-3′ and inserted into the cut vector.

Gene constructs

pEXA2 was cut with MluI and EagI and purified with QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Westberg, Germany). Primers with overhanging restriction sites were used to amplify the genes from an in-house libraries of the ATV virus and pNOB8. PCR fragments were purified using either QIAquick PCR purification kit or QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Westberg, Germany), before cutting with MluI and EagI and ligating into the cut pEXA2 vector. Correct inserts were verified by restriction analyses and DNA sequencing.

Site-directed mutagenesis was accomplished using mutagenic primers as described by Heckman and Pease (2007). Internal mutagenic primers are designed overlapping one another and used with the original gene construct primers to create two intermediate PCR products. These PCR products were then used as template DNA for a second round of PCR to generate the mutated gene.

Determination of transformation efficiencies

Transformation efficiency measurements for the two Sulfolobus strains used are not quantitative for two main reasons. First, the plating material Gel-rite generally contains low and variable levels of pyrimidine compounds, some of which survive autoclaving, and therefore some non-transformants always appear on plates. Moreover, as discussed earlier for the two-layer Gel-rite plating system, some non-transformants appear on plates because of pyrimidines liberated from lysis of dead cells during the long (7–21 days) incubations (Deng et al., 2009). We invariably distinguished transformants from non-transformants by growing them in uracil-deficient media after plating, and for all the experiments where CRISPR loci underwent deletions there were very few viable transformants. Experiments included in Tables 1 and 3 were performed over a 3-year period using different batches of Gel-rite, and competent cells, and therefore we only give the approximate low percentage range of the control transformation efficiencies. Experiments involving altering the PAM motif (Tables 4 and 5) were performed over a shorter time period with one batch of Gel-rite and competent cells. The transformation efficiencies given are averaged and approximate.

Localizing CRISPR locus deletions

PCR reactions were performed with either Taq or Pfu polymerase. Annealing temperatures used were 5°C lower than the estimated Tm of the primer. Elongation times allowed for about 1 min per kilobase pair of the expected product. For the experiment in Fig. S2 elongation times were reduced from 7 min to 2.5 min to enhance the yields of the smaller products. Amplified DNA was purified and generally ran on 0.8% agarose gels with DNA size markers (GeneRuler™ DNA Ladder Mix, 0.1–10 kb, Fermentas).

PCR products were obtained across the chromosomal regions of S. solfataricus P2 CRISPR loci A to D and of S. islandicus REY15A CRISPR loci 1 and 2 using pre-mixed Ex Taq according to the manufacturer's protocol with 75–100 ng of genome DNA in a 10 µl reaction. For S. solfataricus, primer pairs AF: 5′-TGGCGGTTATTAATTGGGA-3′ and AR: 5′-TTGCGGATTCTTGACGTG-3′ and DF: 5′-GCACGCTTCCTACCTTCATTTCCACTAC-3′ and DR: 5′-CATCCCTCTAACCCTTCCCAACCTCATA-3′ were used to amplify the CRISPR loci A and D respectively. For S. islandicus C1F: 5′-AGCTTGCTTACCTCAAGGTACTTTACGT-3′ and C1R: 5′-TTAATAAACGACGATTTTCCTCTTGAT-3′, C2F: 5′-AGGATAGCGAAGTCGTAG AGTTTGGAT-3′ and C2R: 5′-TAACGCACGGTATTGAAACTTCTCATC-3′ were used to amplify CRISPR loci 1 and 2 respectively. Purified PCR products were sequenced directly (Eurofins MWG Operon, Ebersberg, Germany) or first cloned using CloneJET™ PCR Cloning Kit (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) and then sequenced.

RNA preparation and Northern blotting

Total RNA was prepared using Trizol (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) according to the Invitrogen protocol essentially as used for extracting plant si-RNAs (Sunkar et al., 2005). For Northern blotting of small RNAs, 20 µg of RNA was mixed with 10 µl of Gel Loading Buffer II (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, USA) and fractionated in a 6–10% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea, 90 mM Tris, 90 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.3, together with a 10–150 nt ladder (Decade Marker System, Ambion, Huntingdon, UK) or a 0.1–2.0 kb RNA ladder (Invitrogen). Procedures for transferring, and immobilizing RNA on nylon membranes, pre-hybridizing, end-labelling of complementary nucleotides, hybridization and film exposure followed the protocol described earlier (Lillestøl et al., 2009). The following oligonucleotides probes were used for Northern blotting: 5′-TCGGTTCCACATCTAGTTATCAAA-3′ to detect transcription from spacer 29 of CRISPR locus D of S. solfataricus P2; 5′-CCAATCCCAAGATACATCATCG-3′ to detect reverse transcription from the ATV145 gene, and 5′-CGATGATGTATCTTGGGATTGG-3′ to determine forward transcription from ATV145 gene. The latter unlabelled probe was also used as positive control sample for the detection of ATV145 reverse transcription.

Southern blotting

Southern hybridizations followed a standard procedure (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). Genomic DNA was prepared and about 2 µg of total DNA of each sample was digested with XbaI. Resulting DNA fragments were fractionated by agarose gel electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel and transferred onto an IMMOBILON-NY+ membrane (Millipore, Billerica, USA) via capillary transfer. DNAs on the membrane were then auto-cross-linked by the UV Cross-linker (Stratagene, La Jolla, USA). Hybridization probes were amplified by primer probes F 5′-GAAAGTCGCTATTGTCAAAG-3′ and R 5′-AGTCTCATACCCGTTCTCAAAG-3′, purified and labelled with Digoxigenin Labelling kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Hybridization was performed at 59°C overnight. The hybridization signals were detected using the DIG detection kit with the CDP-Star (Roche) with the results recorded by exposing the membrane to CL-XPosure™ X-ray films (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, USA).

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Hien Phan's assistance with DNA analyses. Shiraz A. Shah provided useful bioinformatic insights and discussions. Reidun K. Lillestøl and Xu Peng are thanked for their helpful advice and Reidun K. Lillestøl ran the Northern analysis in Fig. S1. The work was supported by grants from the Danish Natural Science Research Council (Grant No. 272-08-0391), the Danish Research Council for Technology and Production (Grant No. 274-07-0116) and the Danish National Research Foundation.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, Richards M, Boyaval P, Moineau S, et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007;315:1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernander R. The cell cycle of Sulfolobus. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:557–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin A, Quinquis B, Sorokin A, Ehrlich SD. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin. Microbiology. 2005;151:2551–2561. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns SJ, Jore MM, Lundgren M, Westra ER, Slijkhuis RJ, Snijders AP, et al. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science. 2008;321:960–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1159689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Zhu H, Chen Z, Liang YX, She Q. Unmarked gene deletion and host–vector system for the hyperthermophilic crenarchaeon Sulfolobus islandicus. Extremophiles. 2009;13:735–746. doi: 10.1007/s00792-009-0254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveau H, Barrangou R, Garneau JE, Labonté J, Fremaux C, Boyaval P, et al. Phage response to CRISPR-encoded resistance in Streptococcus thermophilus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1390–1400. doi: 10.1128/JB.01412-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I, Vergnaud G, Pourcel C. CRISPRcompar: a website to compare clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:145–148. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale C, Kleppe K, Terns RM, Terns MP. Prokaryotic silencing (psi)RNAs in Pyrococcus furiosus. RNA. 2008;14:1–8. doi: 10.1261/rna.1246808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CR, Zhao P, Olson S, Duff MO, Graveley BR, Wells L, et al. RNA-guided RNA cleavage by a CRISPR RNA–Cas protein complex. Cell. 2009;139:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman KL, Pease LR. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:924–932. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held NL, Whitaker RJ. Viral biogeography revealed by signatures in Sulfolobus islandicus genomes. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:457–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath P, Romero DA, Coûté-Monvoisin A-C, Richards M, Deveau H, Moineau S, et al. Diversity, activity, and evolution of CRISPR loci in Streptococcus thermophilus. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:1401–1412. doi: 10.1128/JB.01415-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R, Embden JD, Gaastra W, Schouls LM. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:1565–1575. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karginov FV, Hannon GJ. The CRISPR system: small RNA-guided defense in bacteria and archaea. Mol Cell. 2010;37:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillestøl RK, Redder P, Garrett RA, Brügger K. A putative viral defence mechanism in archaeal cells. Archaea. 2006;2:59–72. doi: 10.1155/2006/542818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillestøl RK, Shah SA, Brügger K, Redder P, Phan H, Christiansen J, Garrett RA. CRISPR families of the crenarchaeal genius Sulfolobus: bidirectional transcription and dynamic properties. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:259–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Grishin NV, Shabalina SA, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. A putative RNA-interference-based immune system in prokaryotes: computational analysis of the predicted enzymatic machinery, functional analogies with eukaryotic RNAi, and hypothetical mechanisms of action. Biol Direct. 2006;1:7. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ. CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in Staphylococci by targeting DNA. Science. 2008;322:1843–1845. doi: 10.1126/science.1165771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ. Self versus non-self discrimination during CRISPR RNA-directed immunity. Nature. 2010;463:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature08703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martusewitsch E, Sensen CW, Schleper C. High spontaneous mutation rate in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus is mediated by transposable elements. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2574–2581. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2574-2581.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojica FJ, Diez-Villasenor C, Garcia-Martinez J, Soria E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J Mol Evol. 2005;60:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng N, Xia Q, Chen Z, Liang YX, She Q. An upstream activation element exerting differential transcription activation on an archaeal promoter. Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:928–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Brügger K, Shen B, Chen L, She Q, Garrett RA. Genus-specific protein binding to the large clusters of DNA repeats (Short Regularly Spaced Repeats) present in Sulfolobus genomes. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2410–2417. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.8.2410-2417.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourcel C, Salvignol G, Vergnaud G. CRISPR elements in Yersinia pestis acquire new repeats by preferential uptake of bacteriophage DNA, and provide additional tools for evolutionary studies. Microbiology. 2005;151:653–663. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prangishvili D, Forterre P, Garrett RA. Viruses of the Archaea: a unifying view. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006a;11:837–848. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prangishvili D, Vestergaard G, Häring M, Aramayo R, Basta T, Rachel R, Garrett RA. Structural and genomic properties of the hyperthermophilic archaeal virus ATV with an extracellular stage of the reproductive cycle. J Mol Biol. 2006b;359:1203–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pul U, Wurm R, Arslan Z, Geissen R, Hofmann N, Wagner R. Identification and characterization of E. coli CRISPR-cas promoters and their silencing by H-NS. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:1495–1512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redder P, Garrett RA. Mutations and rearrangements in the genome of Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4198–4206. doi: 10.1128/JB.00061-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning : A Laboratory Manual. 3rd edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shah SA, Garrett RA. CRISPR/Cas and Cmr modules, mobility and evolution of adaptive immune systems. Res Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.09.001. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SA, Hansen NR, Garrett RA. Distributions of CRISPR spacer matches in viruses and plasmids of crenarchaeal acidothermophiles and implications for their inhibitory mechanism. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:23–28. doi: 10.1042/BST0370023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She Q, Phan H, Garrett RA, Albers S-V, Stedman KM, Zillig W. Genetic profile of pNOB8 from Sulfolobus: the first conjugative plasmid from an archaeon. Extremophiles. 1998;2:417–425. doi: 10.1007/s007920050087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkar R, Girke T, Zhu JK. Identification and characterization of endogenous small interfering RNAs from rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4443–4454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T-H, Bachellerie J-P, Rozhdestvensky T, Bortolin M-L, Huber H, Drungowski M, et al. Identification of 86 candidates for small non-messenger RNAs from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7536–7541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112047299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T-H, Polacek N, Zywicki M, Huber H, Brügger K, Garrett R, et al. Identification of novel non-coding RNAs as potential antisense regulators in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:469–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.