Adult neural function requires MeCP2 (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2012 Jan 8.

Published in final edited form as: Science. 2011 Jun 2;333(6039):186. doi: 10.1126/science.1206593

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a post-natal neurological disorder characterized by autistic symptoms, cognitive and motor abnormalities, as well as decreased brain growth during childhood (1). RTT is due to mutations in MECP2, which encodes the epigenetic regulator Methyl-CpG-Binding Protein 2 (MeCP2). The onset of RTT symptoms during a critical period of brain development suggests that the function of MeCP2 in the maturing nervous system is critical for establishing normal adult neurological function. Although recent evidence (2) has shown that re-expression of MeCP2 in symptomatic mice that lack Mecp2 rescues several features of disease, it remains unknown whether providing MeCP2 function exclusively during early post-natal life might be sufficient to prevent or mitigate disease in adult animals. In other words, if the nervous system establishes a normal epigenetic program during early life, would neurological function be protected following later loss of MeCP2?

To address this question, we developed an adult onset model of RTT by crossing mice harboring a floxed Mecp2 allele (Mecp2flox (3)) and a tamoxifen-inducible CreER allele (4) to delete Mecp2 when animals are fully mature (post-natal day 60 or older). Thus, MeCP2 expression is eliminated only during adult life. Tamoxifen given daily I.P. at 100mg/kg for 20 days effectively reduces whole-brain MeCP2 levels in Mecp2flox/y; CreER+/− mice (Fig. 1A–B). Vehicle-treated Mecp2flox/y; CreER+/− mice did not experience significant recombination (Fig. S1A-B).

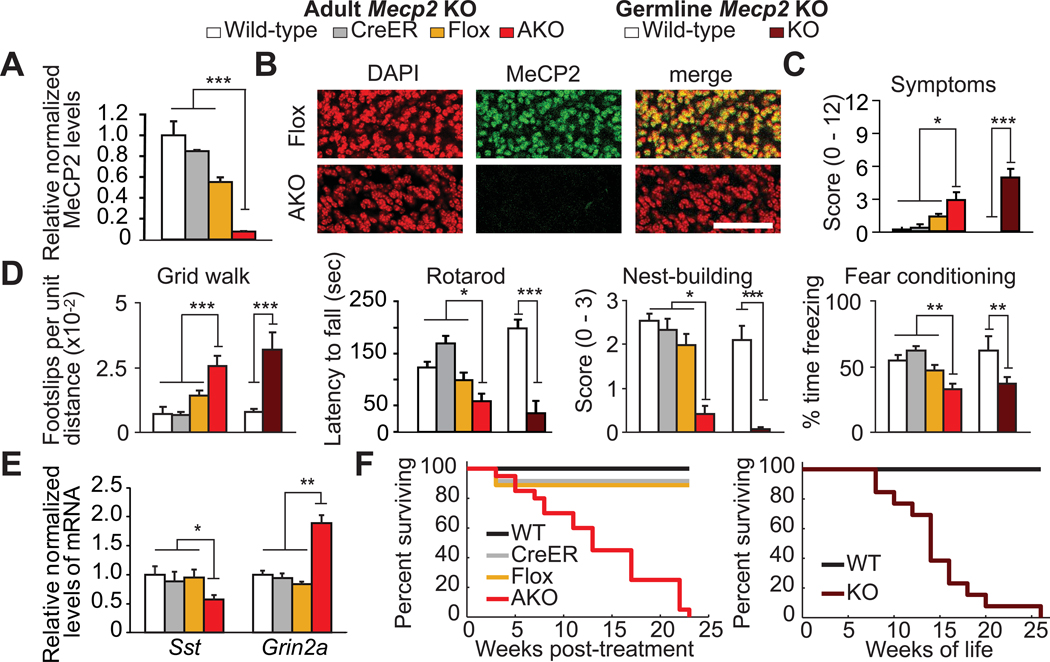

Figure 1. Adult deletion of Mecp2 recapitulates germline knock-out.

(A–B) MeCP2 is depleted in adult knock-out (AKO) mice by western blot of brain lysates (A, N= 3–4 mice per genotype), and by immunofluorescence in cerebellum (B). Scale bar = 50um. (C) AKO mice display symptoms of disease. N= 6–12 per genotype. (D) AKO mice develop motor and learning impairments similar to germline Mecp2null/y (KO) mice. N=10–26 per genotype. (E) Sst and Grin2a mRNA levels are altered in AKO mice. N = 4–12 per genotype. (F) AKO mice die prematurely (left) similar to KO mice (right). N=10–26 per genotype. Data presented as mean ± s.e.m. (*) p<0.05, (**) p<0.01, or (***) p<0.001.

Mice lacking Mecp2 as adults (AKO) develop symptoms of disease and behavioral deficits similar to germline null (KO) mice. By 10 weeks after dosing, AKO mice are less active, have abnormal gait, and develop hind-limb clasping, similar to 10–11 week old KO mice (Fig. 1C). AKO mice also develop motor abnormalities and impaired nesting ability, as observed in KO mice (Fig. 1D). In addition, both AKO and KO mice show impaired learning and memory (Fig. 1D).

Adult deletion of Mecp2 also demonstrates that some genes whose expression is sensitive to MeCP2 levels are altered in its absence (5). In total, we tested 10 genes whose expression is known to be altered in KO mice (Sst, Grin2a, Htr1a, Oprk1, Tac1, Nxph4, Bdnf, Gal, Lphn2, Odz3) and 60% are significantly altered in AKO animals compared to wild-type controls (p<0.05) (Fig. 1E, S2). However, four of these altered genes (Htr1a, Oprk1, Tac1, Nxph4) are also significantly altered in control Mecp2flox mice (p<0.05), suggesting increased sensitivity of these loci to MeCP2 function (Fig. S2).

Finally, both AKO and KO mice die prematurely with similar median time to death (13 weeks following dosing period (n=20) vs 13.3 weeks of life (n=13), respectively) (Fig. 1F).

Taken together, multiple features of disease in a mouse model of RTT can be recapitulated following adult deletion of Mecp2, including disease symptoms, behavioral deficits, gene expression changes, and premature death, indicating that expression of MeCP2 during early life provides little if any protection against the disease. Therefore, unlike the effects of some long-lasting epigenetic instructions that are programmed during early life(6), the effects of MeCP2 on gene expression and neurological function appear to be lost soon after deletion. Moreover, this result argues that the temporal association of disease with the post-natal period of neurodevelopment may be unrelated to any “developmental” or stage-restricted function of MeCP2, at least in mouse models. The interpretation of MeCP2 function presented here is consistent with the findings of Guy et al.(2). However, the previous study does not exclude the possibility that rescue following re-expression of MeCP2 could have been achieved in part by reinvigorating stalled neurodevelopmental processes, which would have predicted that AKO mice should be partly protected against disease. Our results rule out this possibility and decisively show the dependence of the mature brain on MeCP2 function. Lastly, these findings suggest that therapies for RTT, like MeCP2 function, must be continuously maintained.

Supplementary Material

SuppFig1

SuppFig2

SuppReferences

SuppText

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Baker, Y. Lee, A. Flora, and L. Chen for discussions and NIH (grants NS057819, HD024064 to HZ; F31-NS073317 to CM; T32-NS043124 to RS), Baylor Research Advocates for Student Scientists (CM), International Rett Syndrome Foundation, Simons Foundation, and Rett Syndrome Research Trust (HZ) for support.

References

- 1.Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. Neuron. 2007;56:422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guy J, Gan J, Selfridge J, Cobb S, Bird A. Science. 2007;315:1143–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.1138389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guy J, Hendrich B, Holmes M, Martin JE, Bird A. Nat Genet. 2001;27:322–326. doi: 10.1038/85899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayashi S, McMahon AP. Developmental Biology. 2002;244:305–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chahrour M, et al. Science. 2008;320:1224–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver ICG, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SuppFig1

SuppFig2

SuppReferences

SuppText