The effect of combination treatment with aliskiren and blockers of the renin-angiotensin system on hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury: systematic review and meta-analysis (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objective To examine the safety of using aliskiren combined with agents used to block the renin-angiotensin system.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources Medline, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and two trial registries, published up to 7 May 2011.

Study selection Published and unpublished randomised controlled trials that compared combined treatment using aliskiren and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers with monotherapy using these agents for at least four weeks and that provided numerical data on the adverse event outcomes of hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury. A random effects model was used to calculate pooled risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals for these outcomes.

Results 10 randomised controlled studies (4814 participants) were included in the analysis. Combination therapy with aliskiren and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers significantly increased the risk of hyperkalaemia compared with monotherapy using angiotensin converting enzymes or angiotensin receptor blockers (relative risk 1.58, 95% confidence interval 1.24 to 2.02) or aliskiren alone (1.67, 1.01 to 2.79). The risk of acute kidney injury did not differ significantly between the combined therapy and monotherapy groups (1.14, 0.68 to 1.89).

Conclusion Use of aliskerin in combination with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with an increased risk for hyperkalaemia. The combined use of these agents warrants careful monitoring of serum potassium levels.

Introduction

Blockade of the renin-angiotensin system using angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers has been advocated for the management of congestive heart failure, hypertension, and proteinuria.1 2 The opportunity to block the renin-angiotensin system at multiple foci has a compelling biological rationale but may be associated with significant toxicity.3 4 5 6

Direct inhibition of renin—the most proximal aspect of the renin-angiotensin system—became clinically feasible from 2007 with the introduction of aliskiren (Rasilez; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Switzerland). Aliskiren has been shown to be efficacious for the management of hypertension, congestive heart failure, and proteinuria either as monotherapy7 8 or in combination with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers.9 10 11 12 In Ontario, Canada (estimated population 13 million), the use of aliskiren has increased from 56 603 individual prescriptions in 2009 to 119 891 in 2010.13

The publication of the Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET) highlighted the danger of dual inhibition of the renin-angiotensin system, reporting an increased risk of acute dialysis and hyperkalaemia in patients prescribed ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers together.5 These results led scientific organisations to caution against the use of combination therapy using ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers.14 15 16 17 As a blocker of the renin-angiotensin system, aliskiren may be associated with similar adverse effects as ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers, especially when used in combination with these agents. Hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury constitute the most serious consequences of blocking the renin-angiotensin system and have been shown to lead to increased morbidity and mortality.18 19 20 To date, most trials comparing combination therapy with aliskiren and renin-angiotensin system blockers have focused on surrogate outcomes and have been underpowered to provide robust estimates of adverse events.9 11 21 22 23 24 25

Given the increasing popularity of aliskiren, particularly in combination with other renin-angiotensin system blockers, it is important to determine whether its use in combination with these agents is associated with potentially life threatening safety events. We carried out a systematic review and meta-analyses of the safety of using aliskiren combined with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker.

Methods

We used a strategy developed with a health informatics specialist (see web extra on bmj.com) to search Ovid Medline (1948 to 7 May 2011), Embase (1980 to 7 May 2011), and the Cochrane central register of controlled trials (1993 to 7 May 2011). No language restrictions were applied and we reviewed the bibliographies of identified articles to locate further eligible studies. In addition we searched the Clinical trials registry (www.clinicaltrials.gov), the Novartis clinical trial results database, and abstracts of the past five years from conferences of the American Society of Nephrology and the European Renal Association for ongoing or completed trials.

Study selection and validity assessment

We included all randomised controlled clinical trials of at least four weeks’ duration involving aliskiren in combination with either ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers that provided data on the incidence of hyperkalaemia or acute kidney injury relative to monotherapy with aliskiren, an ACE inhibitor, or an angiotensin receptor blocker. Where necessary we contacted corresponding authors for additional missing data. For crossover studies, we used only the first phase.

All dosing regimens of aliskiren, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers were considered, and all ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers used in clinical practice were eligible for inclusion. For the purpose of the analyses we considered ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers together as one class.

We excluded drug combinations with agents other than ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers—for example, combined telmisartan and hydrochlorothiazide. Studies that enrolled patients who were receiving chronic dialysis and studies published only as abstracts were excluded. We also excluded one study with missing information that could not be obtained from the authors.26 Where more than one publication of a trial existed or when a retrospective subgroup analysis was published we used the most complete publication. Studies for which risk of bias could not be determined in any of the domains of our assessment were excluded. We also excluded observational studies, case series, letters, commentaries, reviews, and editorials.

Two authors (ZH and CG) scanned titles and abstracts for initial selection. Selected articles were reviewed in full and independently assessed for eligibility by the same two reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was hyperkalaemia, defined as a serum potassium concentration greater than 5.5 mmol/L (meq/L). The secondary outcomes included acute kidney injury, defined as a serum creatinine concentration greater than 176.8 µmol/L (>2.0 mg/dL), and the severity of hyperkalaemia stratified into moderate (serum potassium concentration 5.5-5.9 mmol/L) and severe (≥6.0 mmol/L).

Assessment of risk of bias

Two reviewers (ZH and CG) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies without blinding to authorship or journal by using the predefined checklist of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.27 The checklist assessed risk of bias in sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, attrition, selection bias, and other biases. In particular, because we were assessing the risk of adverse outcomes, for the domain of attrition we evaluated studies for attrition in reporting outcomes of interest and not the primary outcome of the study. In the domain of other biases, we determined whether an assessment of adverse effects was planned a priori. The classification in each category was yes, no, or unclear. We carried out an overall assessment of the risk of bias based on the responses for the selected criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus and involvement of the other reviewers.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers (ZH and CG) independently extracted data by using custom made data extraction forms. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. The original data were not modified and we carried out calculations from the available data for the meta-analysis. For binary outcome variables (hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury) we calculated risk ratios, risk differences, and numbers needed to harm (NNH), along with 95% confidence intervals. As we anticipated clinical and statistical heterogeneity, we used a random effects model because it accounts to an extent for variability within and between studies. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochrane Q test (significance set at 0.01) and by I² values. We evaluated publication bias using the funnel plot method.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

We planned subgroup analyses to assess for clinical heterogeneity stemming from the characteristics of our study populations and our interventions. These characteristics included age, sex, comorbidities (chronic kidney disease, proteinuria, congestive heart failure, diabetes), and dose of aliskiren used. Retrospective sensitivity analysis was done on the outcome of severe hyperkalaemia, stratified by patient risk for hyperkalaemia into low and high risk groups. Patients at high risk for hyperkalaemia were those with attributes that predisposed them to hyperkalaemia (for example, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, decompensated heart failure, intravascular volume depletion), or concomitant treatment with drugs that may contribute to hyperkalaemia (for example, β blockers, potassium sparing diuretics, aldosterone antagonists). Sensitivity analyses were planned to assess effects after removal of outlier studies identified in funnel plots.

Results

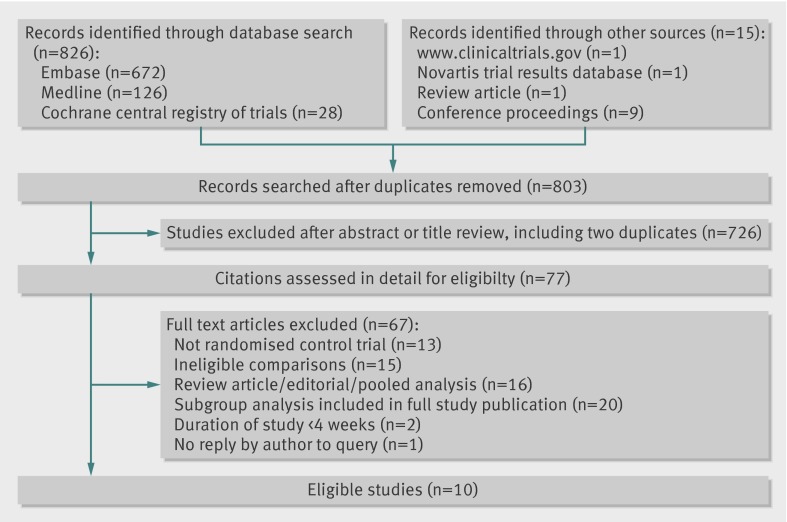

Overall, 841 screened citations met the search criteria. After excluding 38 duplicate citations, 803 citations were evaluated, of which 77 were reviewed in detail. Ten eligible randomised controlled studies were identified and included in this review (fig 1).9 11 21 22 23 24 25 28 29 30

Fig 1 Flow of studies through review

Study participants and interventions

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the included studies and participants. Of the 10 included studies, seven compared the combination of aliskiren and an angiotensin receptor blocker (valsartan, losartan, or irbesartan) with monotherapy using an angiotensin receptor blocker,11 21 23 24 25 28 30 with five of these studies comparing combination therapy with aliskiren monotherapy.11 21 24 25 28 Two studies compared the combination of aliskiren and unspecified ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers with their respective ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker monotherapy,9 22 and one study compared the combination of aliskiren and an ACE inhibitor with ACE inhibitor or aliskiren monotherapy.29 The dosing regimens for aliskiren, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers varied among studies; however, nearly all included studies were designed to reach the maximum recommended doses for aliskiren and the corresponding ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. Study duration ranged from eight to 36 weeks. Participants were mostly male and relatively young. The studies did not include patients with a history of severe renal impairment. Concurrent antihypertensive therapy was used in six studies, including β adrenergic receptor antagonists in four9 22 23 25 and aldosterone antagonists in two.9 22 Most studies included frequent safety assessments of laboratory data; only two studies, however, reported predefined safety outcomes.9 30

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in meta-analysis of safety of combined aliskiren with angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

| Study | Intervention | Targeted dose (mg) | Study duration (weeks) | Mean age (years) | Male (%) | Diabetes (%) | Mean baseline estimated GFR (ml/min) | Study population | Concurrent antihypertensive treatment | Safety outcomes | Safety assessment during study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALLAY 200917 | Aliskiren; losartan; aliskiren and losartan | 300; 10; 300/100 | 36 | 58; 59; 59 | 73; 77; 77 | 23; 22; 27 | 87; 83; 85 | Hypertension; body mass index >25; left ventricular hypertrophy on echocardiogram | Diuretics, calcium channel blockers, vasodilator, α blockers | No primary or secondary safety outcomes | Weeks 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 9-11 |

| ALOFT 20089 | Aliskiren; placebo | 150; NA | 12 | 67; 68 | 80; 76 | 31; 30 | 70; 68 | History of hypertension; NHYA class 2-4 congestive heart failure; brain natriuretic peptide >100 pg/mL; stable dose of ACE inhibitor or ARB and β blocker | β blockers, aldosterone antagonists | Primary outcome of hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury | Weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 |

| ASPIRE 201122 | Aliskiren; placebo | 300; NA | 36 | 61; 59 | 81; 85 | 23; 22 | 80; 81 | 2-8 weeks after AMI; stable dose of ACE or ARB; left ventricular ejection fraction <45% and infarct size ≥20% on echocardiogram | β blockers, aldosterone antagonists | No primary or secondary safety outcomes | Unclear |

| AVANTE GARDE 201025 | Aliskiren; valsartan; aliskiren and valsartan; placebo | 300; 320; 300/320; NA | 8 | 63; 64; 63; 63 | 68; 73; 69; 63 | 19; 21; 21; 20 | 76; 75; 74; 76 | Documented acute coronary syndrome; raised brain natriuretic peptide levels 3-10 days after acute coronary syndrome; clinically stable | β blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics | No primary or secondary safety outcomes | Weeks 1, 2, and 4-8 |

| AVOID 200819 | Losartan; aliskiren and losartan | 100; 300/100 | 24 | 62; 60 | 74; 68 | 100; 100 | 67; 69 | Diabetes mellitus type 2; diabetic nephropathy | Diuretics, calcium channel blockers, vasodilator, α blockers, β blockers | No primary or secondary safety outcomes | Weeks 1 ,4, 8, 11, 12, 16, and 24 |

| Oparil 200723 | Aliskiren; valsartan; aliskiren and valsartan; placebo | 300; 320; 300/320; NA | 8 | 52; 52; 52; 53 | 58; 62; 62; 61 | NA | NA | Stage I-II hypertension | None | No primary or secondary safety outcomes | Weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8 |

| Persson 200920 | Aliskiren; irbesartan; aliskiren and irbesartan; placebo | 300; 300; 300/300; NA | 8 | 60; 59; 61; 61 | 63; 78; 86; 78 | 100; 100; 100; 100 | NA | Diabetes mellitus 2; urine albumin excretion rate >100 mg/24 hours; blood pressure >135/85 mm Hg; GFR >40 mL/min | Diuretics | No primary or secondary safety outcomes | At conclusion of study |

| Pool 200711 | Aliskiren; valsartan; aliskiren and valsartan; aliskiren and hydrochlorothiazide; placebo | 75/150/300; 80/160/320; 150/160 and 300/320; 150/12.5; NA | 8 | 56; 56; 57; 57; 56 | 56; 55; 55; 61; 55 | 8; 7; 11; 2; 8 | NA | Mild to moderate hypertension | None | No primary or secondary safety outcomes | Weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 |

| Uresin 200724 | Aliskiren; ramipril; aliskiren and ramipril | 300; 10; 300/10 | 8 | 60; 60; 59 | 55; 60; 61 | 100; 100; 100 | NA | Diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2; stage I-II hypertension; stable dose of hypoglycaemic drugs | None | No primary or secondary safety outcomes | Weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8 |

| VANTAGE 201030 | Valsartan; aliskiren and valsartan | 320; 300/320 | 8 | 57; 57 | 47; 54 | 15; 17 | NA | Stage II hypertension | None | Secondary outcome of safety and tolerability of combination therapy | Weeks 2 and 8 |

Risk of bias

The risk of bias was low (see web extra on bmj.com). Seven studies described the methods used for generation of the randomisation sequence, whereas six adequately reported details about allocation concealment. All studies reported blinding of participants and investigators, but only six provided sufficient detail on the methods used to mask study staff, participants, and assessors. This is unlikely to affect safety outcomes, however, as these were based on objective laboratory data. Although safety events were monitored and recorded for all included studies, only two studies provided definitions of such outcomes a priori. Regardless, complete data for hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury were available for 10 and eight studies, respectively. Withdrawal rates for all studies were less than 20%. All included studies were sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of aliskiren.

Outcomes

Hyperkalaemia

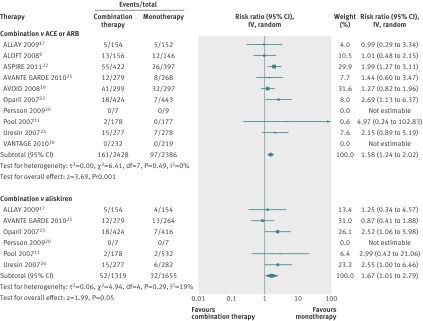

Ten studies reported on the outcome of hyperkalaemia (table 2 and fig 2). All compared the combination of aliskiren and an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker with monotherapy using an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (n=4814). Six studies also compared the combination of aliskiren and an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker with aliskiren monotherapy (n=2974), and six reported on both comparisons. The risk of hyperkalaemia was significantly higher among participants given aliskiren in combination with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker than among those given ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker monotherapy (relative risk 1.58, 95% confidence interval 1.24 to 2.02; risk difference 0.02, 95% confidence interval 0.01 to 0.04; number needed to harm 43, 95% confidence interval 28 to 90; I2=0%). Similarly, the risk of hyperkalaemia from combined use of aliskiren and an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker compared with aliskiren monotherapy was significantly increased (relative risk 1.67, 1.01 to 2.79; risk difference 0.02, 0.03 to 0.01; NNH 50, 33 to 125; I2=19%).

Table 2.

Number of primary and secondary events/total in included studies according to combination therapy or monotherapy

| Study | Hyperkalaemia (serum potassium >5.5 mmol/L) | Acute kidney injury (creatinine >176.8 µmol/L) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aliskiren+ACE inhibitor or ARB | ACE inhibitor or ARB | Aliskiren+ACE inhibitor or ARB | Aliskiren | Aliskiren+ACE inhibitor or ARB | ACE inhibitor or ARB | Aliskiren+ACE inhibitor or ARB | Aliskiren | |

| ALLAY 200917 | 5/154 | 5/152 | 5/154 | 4/154 | 1/154 | 1/152 | 1/154 | 0/154 |

| ALOFT 20089 | 13/156 | 12/146 | NA | NA | 11/156 | 8/146 | NA | NA |

| ASPIRE 201122 | 55/422 | 26/397 | NA | NA | 15/422 | 5/397 | NA | NA |

| AVANTE GARDE 201025 | 12/279 | 8/268 | 12/279 | 13/264 | 3/279 | 3/269 | 3/279 | 6/264 |

| AVOID 200819 | 41/299 | 32/297 | NA | NA | 37/299 | 54/297 | NA | NA |

| Oparil 200723 | 18/424 | 7/443 | 18/424 | 7/416 | 4/426 | 2/445 | 4/426 | 1/417 |

| Persson 200920 | 0/7 | 0/9 | 0/7 | 0/7 | NA | NA | 0/7 | 0/7 |

| Pool 200711 | 2/178 | 0/177 | 2/178 | 2/532 | 0/172 | 0/177 | 0/278 | 1/532 |

| Uresin 200724 | 15/277 | 7/278 | 15/277 | 6/282 | 1/277 | 1/278 | 1/277 | 3/282 |

| VANTAGE 201030 | 0/232 | 0/219 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Fig 2 Risk of hyperkalaemia among participants given combined aliskiren and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) versus monotherapy (ACE inhibitor, ARB, or aliskiren). Values less than 1.0 indicate a decreased risk of outcome with combination therapy

Acute kidney injury

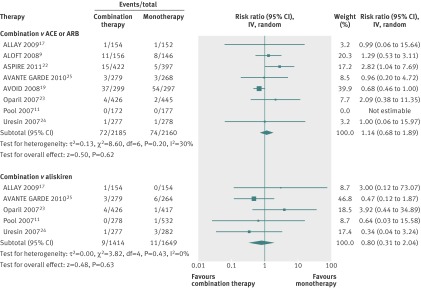

Eight studies reported on acute kidney injury as an outcome measure (fig 3). Six compared the combination of aliskiren and an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker with aliskiren monotherapy (n=3063), and eight compared the combination of aliskiren and an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker with ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker monotherapy (n=4345); five studies reported on both comparisons. The risk of acute kidney injury was not significantly increased among participants given aliskiren in combination with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker than among those given ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker monotherapy (relative risk 1.14, 95% confidence interval 0.68 to 1.89; I2=30%) or aliskiren monotherapy (0.80, 0.31 to 2.04; I2=0%).

Fig 3 Risk of acute kidney injury among participants given combined aliskiren and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) versus monotherapy (ACE inhibitor, ARB, or aliskiren). Values less than 1.0 indicate a decreased risk of outcome with combination therapy

Moderate and severe hyperkalaemia

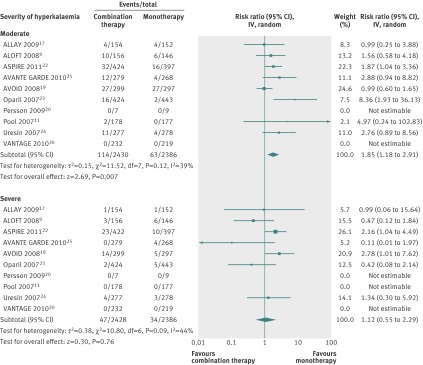

Ten studies compared the combination of aliskiren and an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker with ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker monotherapy (n=4814), and six compared combination therapy with aliskiren monotherapy (n=2974; fig 4). Combination therapy was associated with a significantly increased risk of moderate hyperkalaemia compared with ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker monotherapy (relative risk 1.85, 1.18 to 2.91; risk difference 0.02, 0.01 to 0.03; NNH 50, 33 to 100) as well as aliskiren monotherapy (relative risk 4.04, 2.12 to 7.71; risk difference 0.03, 0.02 to 0.04; NNH 33, 25 to 50). In contrast, the risk for severe hyperkalaemia did not differ with use of combination therapy compared with monotherapy with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (relative risk 1.12, 0.55 to 2.29) or monotherapy with aliskiren (0.45, 0.53 to 1.53).

Fig 4 Risk of hyperkalaemia stratified by severity among participants given combination therapy with aliskiren and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) versus monotherapy with ACE inhibitor or ARB. Values less than 1.0 indicate a decreased risk of outcome with combination therapy

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis

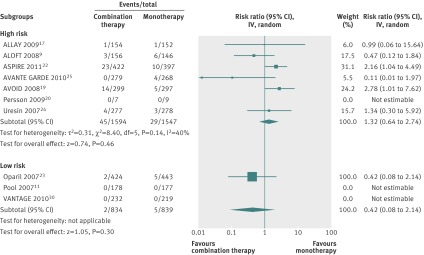

Planned subgroup analyses were not possible from available data, and patient level data could not be obtained. A retrospective sensitivity analysis was carried out on the outcome severe hyperkalaemia, stratifying patients by their risk of hyperkalaemia into low and high risk groups (fig 5). Seven studies enrolled patients at high risk for hyperkalaemia (n=3141) and three enrolled patients at low risk (n=1673). Meta-analysis found that combination therapy did not significantly increase the risk for severe hyperkalaemia in both groups: relative risk in high risk patients 1.32 (95% confidence interval 0.64 to 2.74) and in low risk patients 0.42 (0.08 to 2.14).

Fig 5 Risk of severe hyperkalaemia stratified by high and low risk participants given combination therapy with aliskiren and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) versus monotherapy with ACE inhibitor or ARB. Values less than 1.0 indicate a decreased risk of outcome with combination therapy

Publication bias

No evidence of publication bias for the primary outcome was suggested by visual inspection of the funnel plots (see web extra fig 1). The effect of two outlying studies on the hyperkalaemia outcome were assessed using a sensitivity analysis. Removal of each of these studies decreased the magnitude of the effect for the risk of hyperkalaemia using combination therapy with aliskiren and ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers compared with monotherapy with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (relative risk 1.51, 95% confidence interval 1.17 to1.95) or monotherapy with aliskiren (1.62, 0.91 to 2.87).

Discussion

In this systematic review, we identified a significantly increased risk of hyperkalaemia among people prescribed aliskiren (Rasilez; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Switzerland) in combination with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker compared with those prescribed monotherapy using aliskiren, an ACE inhibitor, or angiotensin receptor blocker. This risk was about 50% greater in those prescribed combination therapy than among those receiving ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker monotherapy, and was about 70% greater in those prescribed combination therapy than among those receiving aliskiren monotherapy. We found no evidence of a significant difference in the risk of acute kidney injury between the study groups.

To date, no published systematic reviews or meta-analyses have evaluated the safety of combination therapy with aliskiren and ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. Previously published pooled analyses of the safety of aliskiren have provided discordant conclusions.31 32 This may have resulted from clinical and methodological heterogeneity between these studies. Our findings differ from those reported previously by one study,31 which showed no difference in the incidence of hyperkalaemia with combined aliskiren and valsartan therapy. However, only three of the trials we analysed were also analysed by that study. In accordance with our results, another study32 concluded that the incidence of hyperkalaemia was higher in those using combined aliskiren and angiotensin receptor blockers compared with those using angiotensin receptor blockers alone. We included the studies evaluated by these two reviews and incorporated findings from six recently completed randomised trials.

The studies included in this meta-analysis show variable statistical and clinical heterogeneity. Given that this meta-analysis focused on adverse events, which are relatively infrequent outcomes, the noticeable clinical heterogeneity among the included studies was to be expected. The populations studied varied widely and included patients with hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and recent acute coronary syndrome. Although including such a heterogeneous group may increase the generalisability of our review, it may also bias the results because these populations possess differential risks for hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury. However, patients at high risk for hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury represent an important segment of current clinical practice and their exclusion makes little sense.

Our stratified analysis of hyperkalaemia by severity showed that combination therapy was associated with a significantly increased risk of moderate but not severe hyperkalaemia. To further explore any heterogeneity in the risk of severe hyperkalaemia, we assessed high and low risk populations in a retrospective sensitivity analysis. The lack of an increased risk of severe hyperkalaemia persisted in both populations, in contrast with previous studies that showed an increased risk of hyperkalaemia associated morbidity and mortality among high risk patients, owing to the interaction of multiple blockers of the renin-angiotensin system that was accentuated by other drugs and coexisting conditions.14 15 Our results may also be explained by the close follow-up of participants, which may have mitigated any differences in baseline risk through adjustments in the management of participants with moderate hyperkalaemia.

The lack of a significantly increased risk of acute kidney injury in our meta-analysis is interesting. Drugs used to block the renin-angiotensin system affect renal haemodynamics primarily through dilation of the efferent arteriole, leading to reduced intraglomerular pressure.29 30 31 As with hyperkalaemia, certain populations possess an increased risk for acute kidney injury owing to pre-existing comorbidity and the use of drugs that may contribute to intravascular volume depletion. These factors may potentiate the effects of renin-angiotensin system blockade using drugs. Aside from the Aliskiren Study in Post-MI patients to Reduce rEmodelling (ASPIRE) study,22 high risk patients in our study had a decreased risk of acute kidney injury compared with their low risk counterparts. As with hyperkalaemia, this trend may result from close follow-up in addition to an extremely conservative serum creatinine threshold used to define acute kidney injury in the included studies, which may have missed many milder cases of acute kidney injury. In fact, current definitions of acute kidney injury, such as the Acute Kidney Injury Network and RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss and End-Stage Renal Disease) criteria, identify acute kidney injury by increases in serum creatinine concentration as small as 26.8 µmol/L (0.3 mg/dL).33 Finally, the relatively short duration of follow-up in the included studies may have also underestimated the true incidence of acute kidney injury. Hyperkalaemia often ensues shortly after receipt of a renin-angiotensin system blocking agent, whereas acute kidney injury usually occurs later after a superimposed renal insult. The short duration of follow-up may have thereby missed these late events.

Quality of the evidence

Most of the trials included in the review were of good quality. A methodological consideration that may have affected study results is the potential lack of standardisation of the creatinine assays among the included studies, which was reported in only two studies.10 20 As there are four assays currently in use to measure serum creatinine levels, each with different performance characteristics, measurement bias may have been introduced when the studies were pooled.

Strengths and limitations of the review

Our review has several strengths. It is the first review describing safety problems associated with use of aliskiren. Our search strategy was broad and included published as well as unpublished sources to capture all safety events. Two independent investigators also rigorously assessed methodological quality.

Our study also has several limitations. We pooled the results of a group of studies that were not originally intended to explore safety outcomes. Many of these included studies were small, resulting in few adverse safety events. As a result, the confidence intervals for the risk ratios for hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury for individual studies were wide; however, meta-analytical estimates were not met with wider uncertainty. Furthermore, we did not have access to original data for any of these studies and included participants who were clinically heterogeneous. Thus we were unable to account for all important differences in the risk for hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury between different groups. It is notable that most patients had preserved baseline kidney function, which may have limited the likelihood of hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury, even among those exposed to renin-angiotensin system blockade using combination therapy.

Implications for practice and future research

Thus far, combination therapy with aliskiren and ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers has shown efficacy only on surrogate end points.9 19 23 Trials evaluating the effect of combination therapy with aliskiren on important outcomes have yet to be published. The Aliskiren Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardiovascular and Renal Disease Endpoints (ALTITUDE) and Efficacy and Safety of Aliskiren and Aliskiren/Enalapril Combination on Morbi-mortality in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure (ATMOSPHERE) trials will evaluate and clarify the role of combination therapy with aliskiren and ACE inhibitors on important clinical outcomes; thus providing clinicians with useful insights into the rational use of such therapy.34 35 Until that time, patients receiving combination treatment including aliskiren for renin-angiotensin system blockade warrant careful monitoring of serum potassium levels. Additionally, although an increased risk for severe hyperkalaemia was not shown in our meta-analysis, our review included randomised controlled trials that enrolled carefully selected populations with relatively preserved kidney function. As such, the generalisability of our findings (and particularly the risk for severe hyperkalaemia) to routine clinical practice is unknown. As such, applying our findings into real world practice must be done with caution as there is a danger of extrapolating the findings of landmark clinical trials to patients who may be at increased risk of adverse events.14

Conclusion

The use of aliskiren in combination with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with a significantly increased risk of hyperkalaemia compared with monotherapy using ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. We found no effect of combination therapy on the risk of acute kidney injury. Further research to clarify the role and safety of using aliskiren in combination therapy on important clinical outcomes is needed.

What is already known on this topic

- Blockers of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), such as aliskiren, are used to manage many conditions, including congestive heart failure, hypertension, and proteinuria

- Hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury are serious consequences of RAS blockade using combination therapy, leading to increased morbidity and mortality

- Most trials comparing combination therapy with aliskiren and other RAS blockers have focused on surrogate outcomes and have been underpowered to provide robust estimates of adverse events

What this study adds

- Combined use of aliskiren with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers is associated with a significantly increased risk of hyperkalaemia compared with monotherapy with either drugs

- Further research to clarify the role and safety of combination therapy with aliskiren on important clinical outcomes is needed before widespread use can be advocated

We thank Elizabeth Uleryk (librarian) for her help with the search strategy.

Contributors: ZH, RW, CB, JB, and PSS conceived and designed the study. ZH, CG, JB, and PSS analysed and interpreted the data. ZH and PSS drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. ZH had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: None received.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2012;344:e42

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Details of search strategy and

Risk of bias in included trials

References

- 1.Navaneethan SD, Nigwekar SU, Sehgal AR, Strippoli GF. Aldosterone antagonists for preventing the progression of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:542-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfie J, Aparicio LS, Waisman GD. Current strategies to achieve further cardiac and renal protection through enhanced renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition. Rev Recent Clin Trials 2011;6:134-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacKinnon M, Shurraw S, Akbari A, Knoll GA, Jaffey J, Clark HD. Combination therapy with an angiotensin receptor blocker and an ACE inhibitor in proteinuric renal disease: a systematic review of the efficacy and safety data. Am J Kidney Dis 2006;48:8-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips CO, Kashani A, Ko DK, Francis G, Krumholz HM. Adverse effects of combination angiotensin II receptor blockers plus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for left ventricular dysfunction: a quantitative review of data from randomized clinical trials. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1930-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann JF, Schmieder RE, McQueen M, Dyal L, Schumacher H, Pogue J, et al. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:547-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berl T. Review: renal protection by inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2009;10:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Mazzotta G, Martire P, Garofoli M, Gentile G, et al. Aliskiren versus ramipril in hypertension. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 2010;4:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen K, Weinberger MH, Egan B, Constance CM, Wright M, Lukashevich V, et al. Comparative efficacy of aliskiren monotherapy and ramipril monotherapy in patients with stage 2 systolic hypertension: subgroup analysis of a double-blind, active comparator trial. Cardiovasc Ther 2010;28:344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMurray JJ, Pitt B, Latini R, Maggioni AP, Solomon SD, Keefe DL, et al. Effects of the oral direct renin inhibitor aliskiren in patients with symptomatic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2008;1:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parving HH, Persson F, Lewis JB, Lewis EJ, Hollenberg NK. Aliskiren combined with losartan in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2433-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pool JL, Schmieder RE, Azizi M, Aldigier JC, Januszewicz A, Zidek W, et al. Aliskiren, an orally effective renin inhibitor, provides antihypertensive efficacy alone and in combination with valsartan. Am J Hypertens 2007;20:11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien E, Barton J, Nussberger J, Mulcahy D, Jensen C, Dicker P, et al. Aliskiren reduces blood pressure and suppresses plasma renin activity in combination with a thiazide diuretic, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, or an angiotensin receptor blocker. Hypertension 2007;49:276-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.IMS Health. Brogan report on prescriptions of aliskiren in Ontario 2009-2011. 2011. www.imshealth.com

- 14.Campbell NR, Kaczorowski J, Lewanczuk RZ, Feldman R, Poirier L, Kwong MM, et al. 2010 Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) recommendations: the scientific summary—an update of the 2010 theme and the science behind new CHEP recommendations. Can J Cardiol 2010;26:236-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schindler C. ACE-inhibitor, AT1-receptor-antagonist, or both? A clinical pharmacologist’s perspective after publication of the results of ONTARGET. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 2008;2:233-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein M. Re-examining RAS-blocking treatment regimens for abrogating progression of chronic kidney disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2009;5:12-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Messerli FH, Staessen JA, Zannad F. Of fads, fashion, surrogate endpoints and dual RAS blockade. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS, Kopp A, Austin PC, Laupacis A, et al. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. N Engl J Med 2004;351:543-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juurlink DN, Mamdani M, Kopp A, Laupacis A, Redelmeier DA. Drug-drug interactions among elderly patients hospitalized for drug toxicity. JAMA 2003;289:1652-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Moen MF, Seliger SL, et al. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1156-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solomon SD, Appelbaum E, Manning WJ, Verma A, Berglund T, Lukashevich V, et al. Effect of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren, the angiotensin receptor blocker losartan, or both on left ventricular mass in patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 2009;119:530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solomon SD, Shin SH, Shah A, Skali H, Desai A, Kober L, et al. Effect of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren on left ventricular remodelling following myocardial infarction with systolic dysfunction. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1227-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parving HH, Persson F, Lewis JB, Lewis EJ, Hollenberg NK. Aliskiren combined with losartan in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2433-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Persson F, Rossing P, Reinhard H, Juhl T, Stehouwer CD, Schalkwijk C, et al. Renal effects of aliskiren compared with and in combination with irbesartan in patients with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and albuminuria. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1873-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scirica BM, Morrow DA, Bode C, Ruzyllo W, Ruda M, Oude Ophuis AJ, et al. Patients with acute coronary syndromes and elevated levels of natriuretic peptides: the results of the AVANT GARDE-TIMI 43 Trial. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1993-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volkova A, Arutyunov G, Bylova N, Dayter I. Therapy of heart failure in decompensation with direct renin inhibitor and changes in renal function. Eur Heart J 2010;31:848. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley, 2008.

- 28.Oparil S, Yarows SA, Patel S, Fang H, Zhang J, Satlin A. Efficacy and safety of combined use of aliskiren and valsartan in patients with hypertension: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2007;370:221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uresin Y, Taylor AA, Kilo C, Tschope D, Santonastaso M, Ibram G, et al. Efficacy and safety of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren and ramipril alone or in combination in patients with diabetes and hypertension. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2007;8:190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novartis Pharmaceuticals. VANTAGE study: 8 weeks study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of valsartan in combination with aliskiren compared to valsartan alone in patients with stage 2 hypertension. 2010.

- 31.Weir MR, Bush C, Anderson DR, Zhang J, Keefe D, Satlin A. Antihypertensive efficacy, safety, and tolerability of the oral direct renin inhibitor aliskiren in patients with hypertension: a pooled analysis. J Am Soc Hypertens 2007;1:264-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White WB, Bresalier R, Kaplan AP, Palmer BF, Riddell RH, Lesogor A, et al. Safety and tolerability of the direct renin inhibitor aliskiren: a pooled analysis of clinical experience in more than 12,000 patients with hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2010;12:765-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bagshaw SM. Acute kidney injury: diagnosis and classification of AKI: AKIN or RIFLE? Nat Rev Nephrol 2010;6:71-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parving HH, Brenner BM, McMurray JJ, de Zeeuw D, Haffner SM, Solomon SD, et al. Aliskiren Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardio-Renal Endpoints (ALTITUDE): rationale and study design. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009;24:1663-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krum H, Massie B, Abraham WT, Dickstein K, Kober L, McMurray JJ, et al. Direct renin inhibition in addition to or as an alternative to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: rationale and design of the Aliskiren Trial to Minimize OutcomeS in Patients with HEart failuRE (ATMOSPHERE) study. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:107-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Details of search strategy and

Risk of bias in included trials