Early Hospital Readmission is a Predictor of One-Year Mortality in Community-Dwelling Older Medicare Beneficiaries (original) (raw)

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Hospital readmission within thirty days is common among Medicare beneficiaries, but the relationship between rehospitalization and subsequent mortality in older adults is not known.

OBJECTIVE

To compare one-year mortality rates among community-dwelling elderly hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries who did and did not experience early hospital readmission (within 30 days), and to estimate the odds of one-year mortality associated with early hospital readmission and with other patient characteristics.

DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

A cohort study of 2133 hospitalized community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries older than 64 years, who participated in the nationally representative Cost and Use Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey between 2001 and 2004, with follow-up through 2006.

MAIN MEASURE

One-year mortality after index hospitalization discharge.

KEY RESULTS

Three hundred and four (13.7 %) hospitalized beneficiaries had an early hospital readmission. Those with early readmission had higher one-year mortality (38.7 %) than patients who were not readmitted (12.1 %; p < 0.001). Early readmission remained independently associated with mortality after adjustment for sociodemographic factors, health and functional status, medical comorbidity, and index hospitalization-related characteristics [HR (95 % CI) 2.97 (2.24-3.92)]. Other patient characteristics independently associated with mortality included age [1.03 (1.02-1.05) per year], low income [1.39 (1.04-1.86)], limited self-rated health [1.60 (1.20-2.14)], two or more recent hospitalizations [1.47 (1.01-2.15)], mobility difficulty [1.51 (1.03-2.20)], being underweight [1.62 (1.14-2.31)], and several comorbid conditions, including chronic lung disease, cancer, renal failure, and weight loss. Hospitalization-related factors independently associated with mortality included longer length of stay, discharge to a skilled nursing facility for post-acute care, and primary diagnoses of infections, cancer, acute myocardial infarction, and heart failure.

CONCLUSIONS

Among community-dwelling older adults, early hospital readmission is a marker for notably increased risk of one-year mortality. Providers, patients, and families all might respond profitably to an early readmission by reviewing treatment plans and goals of care.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2116-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: readmission, mortality, older adults, care transitions

INTRODUCTION

Medicare, the health insurance program for older Americans and persons with certain disabilities, is examining ways to reduce non-elective hospital readmissions because they are common, costly, and potentially preventable. Among all hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries (including community-dwelling and institutionalized elders, as well as younger disabled Medicare beneficiaries), nearly one in five were readmitted within 30 days, and over one-third were readmitted within 90 days.1 These readmitted individuals have been described in some detail; research has identified early readmission risk factors for general2,3 and geriatric populations,4–6 as well as those with specific diseases such as heart failure,7 stroke,8 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.9 Individuals readmitted early are more likely to have multiple medical comorbidities, greater length of stay during the index hospitalization, and additional recent hospitalizations. Among hospitalized older adults, early readmission has also been associated with age greater than 80, depression, and poor patient education upon discharge.4

Despite the increased attention to readmissions, few previous studies have examined whether early readmission predicts survival. Any hospitalization is known to increase risk of mortality in the year following discharge,10 and other predictors of outcome after hospitalization are emerging, but the effect of early readmission on mortality remains unknown. If early readmission is an independent risk factor for mortality, understanding the causes of this worsened prognosis has significant clinical relevance, and offers the potential for additional interventions that address both patient outcomes and health care costs. For example, readmission might trigger a review of the treatment plan and goals of care. Among discharged older adults, a validated prognostic index is available that stratifies one-year mortality risk as low, intermediate, or high11; a similar assessment tool for the patients who are readmitted might help inform their care.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the association of early hospital readmission and other potential risk factors with one-year mortality among community-dwelling hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries. We focus on community-dwelling elders because they represent a majority of Medicare beneficiaries, and because interventions for institutionalized individuals would likely differ. The factors we identify may prompt or improve interventions designed to prevent readmissions, improve quality of life, and decrease mortality.

METHODS

Study Design, Data Source, and Participants

The cohort for this longitudinal observational study was selected from participants in the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) between 2001 and 2004. Sponsored by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the MCBS sample comprises a rotating panel of beneficiaries that represents the Medicare population as a whole and within age groups. Each participant is followed for up to four years with in-person interviews; the Cost and Use data set only includes the latter three years. The annual health and functional status interview is conducted in the autumn, with an overall response rate of 85-89 %. The survey covers sociodemographic, personal health, functional status, and medical care topics and is linked to Medicare claims data. A detailed description of the MCBS methods and survey questions is available from CMS.12 We defined the baseline interview as the participant’s initial Cost and Use interview. We obtained permission to use the MCBS from CMS through a Data Use Agreement and study approval from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

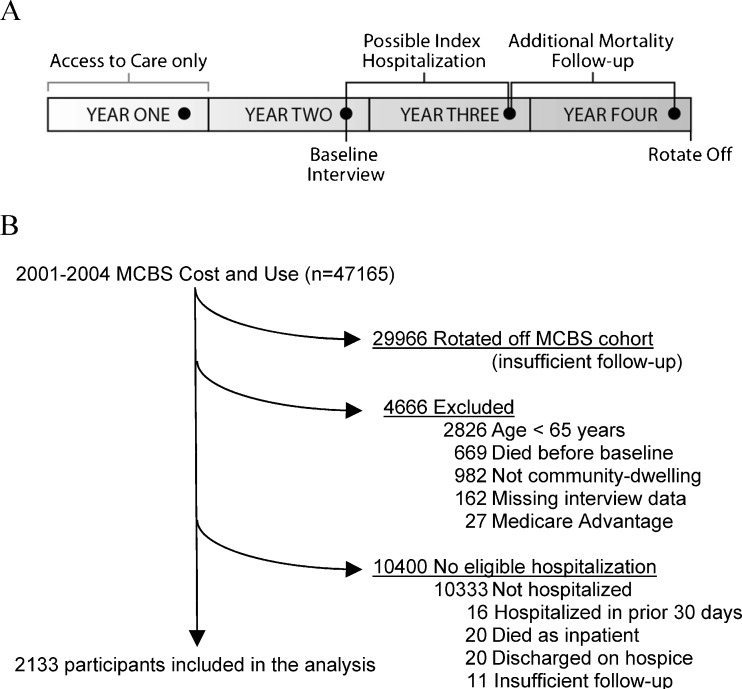

This study includes Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 or older, who were living in the community at the time of the baseline interview and were hospitalized within 365 days. We required that beneficiaries be part of the MCBS cohort for two years after the baseline interview, to ensure sufficient Medicare claims data for follow-up; mortality was assessed in the year after hospitalization. Beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage programs were excluded because their Medicare claims are not complete. Index hospitalizations were excluded if beneficiaries died in hospital or were discharged to hospice. Figure 1a depicts the four-year time line of MCBS participation. For a participant entering in 2003 (Year One), the baseline interview occurred in autumn 2004 (Year Two), index hospitalization was likely in 2005 (Year Three), and data from 2006 (Year Four) were utilized for one-year mortality follow-up. The final cohort is shown in Figure 1b. The proportion of proxy respondents in the cohort (12 %) did not differ by readmission status. Those excluded from the cohort due to missing interview data did not differ in age, race, or gender, but they were more likely to have been hospitalized (36 % vs. 16 %) and to have died (8 % vs 1 %) during the interview calendar year.

Figure 1.

Depiction of study period and participant selection. A) Timeline of MCBS participation. Circles represent annual surveys. Year One is excluded from Cost and Use. Baseline interview, index hospitalization, and mortality follow-up are indicated. B) Derivation of the analytic sample.

Measures

The index hospitalization was defined as the first inpatient hospital claim to occur after the baseline interview. Potential index hospitalizations were excluded if there had been a hospital discharge in the prior 30 days (n = 16). The search for the index hospitalization covered a maximum of 365 days after each participant’s baseline interview date; index hospitalizations had to end by December 1 of the year after the baseline interview, to allow at least 30 post-discharge days to monitor for early readmission. We combined the admissions of patients transferred to another acute care hospital (n = 53) into a single hospitalization event. Early readmission was defined by the presence a hospital claim starting within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization. The time to readmission was calculated as the number of days from date of discharge to date of hospital readmission. One-year mortality rates were determined based on death within 365 days of the index hospitalization discharge date.

In addition to early readmission, we considered four broad categories of potential predictors of mortality: sociodemographic factors, health and functional status, medical comorbidity, and index hospitalization-related characteristics. We chose specific factors a priori, based on clinical relevance or known association with mortality. The sociodemographic factors were age, sex, minority status (self-identification as Hispanic or non-White), living alone, education, and annual income under $25,000.

Health and functional status variables were self-rated health, recent hospitalizations prior to the baseline interview (categorized as zero, one, or two or more), activities of daily living (ADL), mobility, current tobacco use, cognitive and psychiatric symptoms, and body mass index (BMI). We defined limited self-rated health as a response of “fair” or “poor” to the question: “Compared to other people your age, would you say that your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Medicare claims were searched to find hospitalizations in the six months prior to the baseline interview. ADL difficulty was based on report of difficulty or inability to perform any basic ADLs (bathing, dressing, eating, transferring, walking, and toileting). Mobility difficulty was defined as difficulty walking a quarter of a mile, or difficulty with stooping, crouching, or kneeling. Cognitive symptoms were based on report of: 1) being told by a doctor about having dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, or mental retardation; or 2) difficulty with memory loss, making decisions, or concentrating. Psychiatric symptoms were based on: 1) being told by a doctor about having a psychiatric or mental condition, including depression; 2) feeling sad, blue, or depressed most or all of the time; or 3) two weeks or more of lost interest or pleasure in things usually cared about or enjoyed. BMI was calculated from self-reported height and weight.

Medical comorbidities were obtained from two sources. First, self-reported physician-diagnosed chronic conditions were obtained from the baseline interview. Self-reported neurological disease included stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and paralysis. Second, the secondary diagnoses from the index hospitalization were classified according to the Elixhauser classification13 of the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9). When there was a clinically related category with no significant difference in readmission or mortality rates, Elixhauser categories with low prevalence were combined; otherwise very low prevalence (<1 %) categories were eliminated. Several conditions were assessed by both self-report and claims; when this occurred, the two sources were combined, and the condition was considered present when indicated by either source.

Index hospitalization-related characteristics from the Medicare claims data were primary diagnosis category, length of stay, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and post-acute care utilization. Primary diagnosis was based on the primary ICD-9 code from the hospital claim. Given the relatively low prevalence and large number of individual ICD-9 codes, we classified primary diagnoses using Clinical Classification Software (CCS), which classifies diagnoses into four heirarchical levels from Level 1 (organ system) to Level 4 (specific diagnosis).14 Our final classification system is described in detail in the online Appendix. ICU admission was based on claims containing revenue center codes 0200-0219. Post-acute care utilization was categorized as none, home health, skilled nursing facility, and other (e.g. inpatient rehabilitation, psychiatric admission, or long-term acute care), based on claims for the post-acute services.

Statistical Analysis

To identify factors independently associated with readmission and mortality following hospitalization, we ordinalized some continuous variables (e.g. BMI), collapsed some categories within ordinal variables (e.g. self-rated health, education), and combined related chronic conditions. Use of categorical variables allows for non-linear relationships and provides interpretable odds and hazard ratios.

We used multivariable logistic regression to evaluate the independent association of patient and hospitalization characteristics with 30-day readmission. We used multivariable proportional hazards models to determine the factors independently associated with time to mortality after index hospitalization. Primary results are presented as adjusted hazard ratios with 95 % confidence intervals. As sensitivity analyses, we repeated the primary analysis, excluding participants who died during their rehospitalization and comparing the effects of readmission for the same or different diagnoses on mortality. We also examined the association of readmission with one-year mortality using multivariable logistic regression. Sampling weights were used to account for the complex multistage sample design and oversampling of particular groups, such as the oldest old.15 All means and percentages are weighted to reflect the sample design. Analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SAS-callable SUDAAN, version 9.0.0 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC).

RESULTS

The study cohort is composed of 2133 MCBS beneficiaries who were age 65 or older, community-dwelling at the time of the baseline interview, and subsequently hospitalized within one year, and whose MCBS data permitted assessment of early readmission and one-year mortality. The average time from the baseline interview until index hospitalization was 166 days, which was not significantly different among beneficiaries who were or were not readmitted within 30 days (P = 0.54). The early readmission rate was 13.7 % (time to readmission presented in the online Figure). A sensitivity analysis of hospitalized MCBS beneficiaries readmitted within 60 days showed similar results (data not shown).

Table 1 describes the characteristics of beneficiaries and of their index admissions by early readmission status. As expected, readmitted beneficiaries reported worse health and socioeconomic status. Factors independently associated with early readmission included: belonging to a racial or ethnic minority, having two or more hospitalizations in the 6 months prior to the baseline interview, smoking, comorbid conditions (specifically cancer, coronary artery disease, and unintentional weight loss), a primary hospital diagnosis of metastatic cancer, and discharge to a skilled nursing facility.

Table 1.

Baseline and Index Hospitalization Characteristics of Hospitalized Medicare Beneficiaries by Early Readmission Status and Adjusted Associations with Readmission

| Characteristic | No. (%)* | Adjusted OR† (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 2133) | Readmission (n = 304) | No Readmission (n = 1829) | ||

| Sociodemographic | ||||

| Age, mean (SE) | 77.3 (0.2) | 77.9 (0.4) | 77.2 (0.2) | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) |

| Female sex | 1173 (55.1) | 164 (52.8) | 1009 (55.5) | 0.82 (0.60-1.12) |

| Minority‡ | 356 (17.1) | 63 (22.8) | 293 (16.2) | 1.50 (1.07-2.09) |

| Living alone | 714 (31.2) | 107 (32.8) | 607 (30.9) | 1.07 (0.76-1.52) |

| Non-high school graduate | 812 (36.4) | 133 (43.3) | 679 (35.2) | 1.13 (0.84-1.51) |

| Annual income ≤$25,000 | 1337 (62.9) | 214 (69.7) | 1163 (61.8) | 1.09 (0.80-1.49) |

| Health and functional status | ||||

| Limited self-rated health§ | 747 (34.9) | 130 (44.6) | 617 (33.3) | 1.15 (0.85-1.56) |

| Prior hospitalizations║ | ||||

| 0 | 1712 (80.8) | 221 (73.1) | 1491 (82.0) | 1.00 |

| 1 | 300 (13.5) | 52 (16.4) | 248 (13.1) | 1.32 (0.92-1.90) |

| 2 or more | 121 (5.7) | 31 (10.5) | 90 (5.0) | 2.32 (1.48-3.63) |

| Difficulty in any ADL¶ | 938 (42.3) | 161 (51.3) | 777 (40.9) | 1.12 (0.81-1.54) |

| Mobility difficulty | 1587 (72.9) | 241 (77.1) | 1346 (72.3) | 1.00 (0.70-1.42) |

| Current tobacco use | 216 (11.1) | 42 (14.0) | 174 (10.4) | 1.62 (1.06-2.47) |

| Cognitive symptoms | 354 (15.3) | 53 (16.7) | 301 (15.0) | 0.91 (0.61-1.37) |

| Psychiatric symptoms | 605 (27.4) | 86 (29.2) | 519 (27.1) | 0.92 (0.66-1.30) |

| Body mass index | ||||

| <20 | 172 (7.2) | 24 (7.1) | 148 (7.2) | 0.85 (0.51-1.43) |

| 20-25 | 686 (30.6) | 98 (31.1) | 588 (30.6) | 1.00 |

| 25-30 | 782 (37.2) | 110 (36.1) | 672 (37.4) | 1.04 (0.76-1.43) |

| >30 | 493 (25.0) | 72 (25.8) | 421 (24.9) | 1.06 (0.71-1.57) |

| Medical comorbidity_#_ | ||||

| Self-report or claims | ||||

| Heart failure | 371 (16.4) | 70 (21.5) | 301 (15.5) | 0.98 (0.72-1.33) |

| Lung disease | 631 (30.0) | 99 (32.0) | 532 (29.6) | 0.95 (0.72-1.26) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 620 (29.4) | 104 (35.9) | 516 (28.4) | 1.08 (0.81-1.45) |

| Hypertension | 1661 (77.4) | 247 (81.4) | 1414 (76.7) | 1.15 (0.79-1.67) |

| Cancer | 506 (23.9) | 96 (33.3) | 410 (22.4) | 1.45 (1.08-1.93) |

| Arthritis | 1455 (67.4) | 223 (73.3) | 1232 (66.5) | 1.24 (0.92-1.67) |

| Neurological disease | 555 (25.5) | 74 (25.0) | 481 (25.2) | 0.80 (0.58-1.11) |

| Self-report only | ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 767 (35.1) | 136 (44.6) | 631 (33.6) | 1.61 (1.22-2.11) |

| Claims only | ||||

| Heart valve or pulmonary circulatory disease | 232 (10.7) | 40 (13.3) | 192 (10.3) | 1.13 (0.76-1.67) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 119 (5.5) | 19 (6.0) | 100 (5.4) | 0.82 (0.43-1.53) |

| Hypothyroidism | 203 (9.4) | 24 (7.6) | 179 (9.7) | 0.81 (0.49-1.32) |

| Renal failure | 88 (4.1) | 20 (6.3) | 68 (3.7) | 1.09 (0.58-2.03) |

| Anemia or coagulopathy | 299 (13.6) | 49 (16.4) | 250 (13.2) | 1.03 (0.70-1.50) |

| Weight loss | 41 (2.0) | 13 (4.5) | 28 (1.6) | 2.26 (1.11-4.60) |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 379 (17.1) | 72 (21.8) | 307 (16.4) | 1.19 (0.85-1.67) |

| Mental health disorders | 127 (6.1) | 12 (4.5) | 115 (6.5) | 0.54 (0.27-1.07) |

| Hospitalization characteristics | ||||

| Length of stay | ||||

| 0-4 days | 1341 (63.4) | 168 (54.7) | 1173 (64.8) | 1.00 |

| 5-10 days | 615 (28.3) | 92 (30.3) | 523 (28.0) | 0.98 (0.73-1.32) |

| >10 days | 177 (8.3) | 44 (15.0) | 133 (7.2) | 1.43 (0.91-2.22) |

| Intensive care unit admission | 714 (33.7) | 108 (37.0) | 606 (33.2) | 0.98 (0.72-1.35) |

| Primary discharge diagnosis** | ||||

| Infections | 215 (9.7) | 34 (10.7) | 181 (9.5) | 1.13 (0.56-2.26) |

| Non-metastatic cancer | 109 (5.5) | 23 (9.0) | 86 (5.0) | 1.79 (0.86-3.70) |

| Metastatic cancer | 36 (1.9) | 12 (4.5) | 24 (1.5) | 2.64 (1.03-6.79) |

| Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic, hematologic and immune disease | 107 (5.0) | 19 (5.9) | 88 (4.9) | 0.93 (0.43-2.02) |

| Neurologic, sensory, musculoskeletal, and dermatologic diseases | 238 (11.9) | 18 (5.5) | 220 (12.9) | 0.46 (0.21-1.03) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 57 (2.7) | 14 (5.0) | 43 (2.3) | 1.96 (0.78-4.93) |

| Arrhythmias, gastrointestinal disorders, and fractures | 413 (18.8) | 45 (13.9) | 368 (19.6) | 0.74 (0.40-1.38) |

| Heart failure | 116 (5.1) | 24 (7.1) | 92 (4.7) | 1.18 (0.57-2.46) |

| Acute cerebrovascular, non-infectious respiratory, and genitourinary disease | 321 (14.8) | 43 (13.1) | 278 (15.1) | 0.87 (0.45-1.68) |

| Other diseases of the circulatory system | 329 (15.7) | 41 (13.6) | 288 (16.1) | 0.90 (0.47-1.73) |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage or obstruction, hepatic or pancreatic disease | 71 (3.3) | 16 (5.9) | 55 (2.8) | 2.08 (0.92-4.69) |

| Other | 121 (5.6) | 15 (5.9) | 106 (5.6) | 1.00 |

| Post-acute care | ||||

| Home | 1479 (70.5) | 189 (61.5) | 1290 (71.9) | 1.00 |

| Home with home health | 219 (10.5) | 37 (13.0) | 182 (10.1) | 1.45 (0.93-2.28) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 326 (13.8) | 63 (20.8) | 263 (12.7) | 1.96 (1.30-2.96) |

| Other†† | 109 (5.2) | 15 (4.7) | 94 (5.3) | 1.20 (0.65-2.20) |

Among the 304 readmissions, the median (IQR) time to readmission was 11 (4–18) days. The most common readmission diagnoses by CCS Level 3 category were congestive heart failure, pneumonia, coronary atherosclerosis without acute myocardial infarction, cardiac dysrhythmias, and obstructive chronic bronchitis, which together accounted for 25 % of readmissions. Comparing readmission and index hospitalization diagnoses, 66 (22 %) were the same at CCS Level 3, 97 (33 %) at Level 2, and 125 (42 %) at Level 1 (the same organ system). More detail about readmission diagnoses is available in online Table 1.

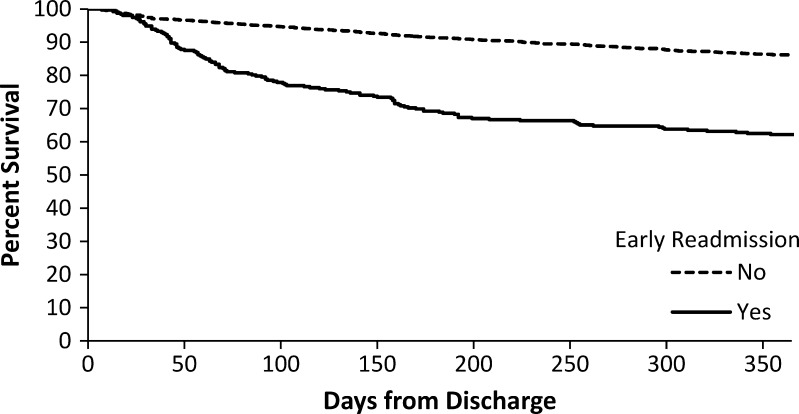

A total of 355 members of the cohort died within one year of index hospitalization discharge, representing an overall weighted mortality rate of 15.7 %. The one-year mortality rate for those with early readmission was 38.7 % compared to 12.1 % in those not readmitted early (p < 0.001), with those readmitted having a shorter time to death (Fig. 2). After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, health and functional status, medical comorbidity, and index hospitalization-related characteristics, early readmission was independently and strongly associated with one-year mortality [HR 2.97 (95 % CI, 2.24-3.92)]. In addition to early readmission, older age, low income, limited self-rated health, two or more prior hospitalizations, mobility difficulty, and low BMI were independently associated with mortality (Table 2). Comorbid conditions associated with mortality included chronic lung disease, cancer, renal failure, and weight loss. Being overweight and comorbid hypertension and arthritis were associated with a reduced risk of one-year mortality. Hospitalization characteristics associated with mortality included longer length of stay, discharge to a skilled nursing facility, and principal diagnoses of infections, cancer, acute myocardial infarction, and heart failure.

Figure 2.

Time to death by 30-day readmission status among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries, aged 65 years or older. Dashed line represents those not readmitted within 30 days, and solid line represents those readmitted within 30 days (log-rank test, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Association of Early Readmission and Baseline and Index Hospitalization Characteristics of Hospitalized Medicare Beneficiaries with Time to Death

| Characteristic | Adjusted HR (95%CI)* |

|---|---|

| Readmission within 30 days of index hospitalization | 2.97 (2.24 - 3.92) |

| Sociodemographic | |

| Age, mean (SE) | 1.03 (1.02 - 1.05) |

| Female sex | 0.78 (0.59 - 1.03) |

| Minority† | 0.97 (0.70 - 1.34) |

| Living alone | 0.80 (0.62 - 1.04) |

| Non-high school graduate | 1.12 (0.86 - 1.44) |

| Annual income ≤$25,000 | 1.39 (1.04 - 1.86) |

| Health and functional status | |

| Limited self-rated health‡ | 1.60 (1.20 - 2.14) |

| Prior hospitalizations§ | |

| 0 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 1.11 (0.81 - 1.52) |

| 2 or more | 1.47 (1.01 - 2.15) |

| Difficulty in any ADL║ | 1.13 (0.83 - 1.54) |

| Mobility difficulty | 1.51 (1.03 - 2.20) |

| Current tobacco use | 1.16 (0.78 - 1.71) |

| Cognitive symptoms | 1.20 (0.86 - 1.67) |

| Psychiatric symptoms | 0.86 (0.64 - 1.14) |

| Body mass index | |

| <20 | 1.62 (1.14 - 2.31) |

| 20-25 | 1.00 |

| 25-30 | 0.72 (0.54 - 0.95) |

| >30 | 0.75 (0.53 - 1.05) |

| Medical comorbidity¶ | |

| Self-report or claims | |

| Heart failure | 1.03 (0.75 - 1.41) |

| Lung disease | 1.30 (1.03 - 1.66) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.85 (0.64 - 1.12) |

| Hypertension | 0.71 (0.53 - 0.94) |

| Cancer | 1.35 (1.02 - 1.79) |

| Arthritis | 0.71 (0.54 - 0.92) |

| Neurological disease | 1.18 (0.90 - 1.56) |

| Self-report only | |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.94 (0.71 - 1.23) |

| Claims only | |

| Heart valve or pulmonary circulatory disease | 1.07 (0.75 - 1.53) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.12 (0.72 - 1.73) |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.87 (0.58 - 1.31) |

| Renal failure | 1.67 (1.11 - 2.53) |

| Anemia or coagulopathy | 0.99 (0.71 - 1.37) |

| Weight loss | 2.09 (1.28 - 3.43) |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 1.29 (0.98 - 1.71) |

| Mental health disorders | 1.26 (0.75 - 2.12) |

| Hospitalization characteristics | |

| Length of stay | |

| 0-4 d | 1.00 |

| 5-10 d | 1.34 (1.01 - 1.77) |

| >10 d | 1.53 (1.02 - 2.29) |

| Intensive care unit admission | 1.09 (0.84 - 1.43) |

| Primary discharge diagnosis# | |

| Infections | 1.94 (1.01 - 3.71) |

| Non-metastatic cancer | 4.63 (2.46 - 8.71) |

| Metastatic cancer | 4.67 (2.07 - 10.54) |

| Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic, hematologic, and immune disease | 1.78 (0.91 - 3.46) |

| Neurologic, sensory, musculoskeletal, and dermatologic diseases | 0.66 (0.28 - 1.54) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2.44 (1.05 - 5.65) |

| Arrhythmias, gastrointestinal disorders, and fractures | 1.64 (0.88 - 3.07) |

| Heart failure | 4.06 (2.04 - 8.08) |

| Acute cerebrovascular, non-infectious respiratory, and genitourinary disease | 1.78 (0.96 - 3.31) |

| Other diseases of the circulatory system | 0.91 (0.46 - 1.80) |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage or obstruction, hepatic or pancreatic disease | 2.16 (0.99 - 4.71) |

| Other | 1.00 |

| Post-acute care | |

| Home | 1.00 |

| Home with home health | 0.85 (0.54 - 1.34) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 1.54 (1.11 - 2.14) |

| Other ** | 0.97 (0.54 - 1.74) |

We performed several sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of our results. Of those beneficiaries readmitted within 30 days, 26 (9 %) died during their rehospitalization. Exclusion of these participants did attenuate the effect of readmission on mortality [HR (95 % CI) 2.43 (1.80-3.27)]; however, readmission remained a strong independent predictor of mortality. We chose to present the results including those who died during the rehospitalization, as formally excluding them would increase the healthy responder or survivor bias in our results. In order to determine if readmission for the same versus a different diagnosis had an impact on the mortality risk, we compared the hazard ratios for those readmitted with the same versus different diagnoses. There were no significant differences in the hazard ratios for readmission with the same versus a different diagnosis at either Level 1 (HRs 2.87 vs. 3.03, p = 0.82), Level 2 (HRs 3.32 vs. 2.80, p = 0.49), or Level 3 (HRs 3.10 vs. 2.92, p = 0.84). As a final sensitivity analysis, we used logistic regression to examine the relationship between readmission and one-year mortality as a dichotomous variable; the overall results were comparable to the time-to-death analysis, with readmission having an OR (95 % CI) of 4.01 (2.83 - 5.69); full results of this analysis are available in Online Table 2.

DISCUSSION

Among this nationally representative sample of community-dwelling older adults, early hospital readmission was associated with markedly increased risk of one-year mortality. This gravely increased risk persists after adjustment for multiple potential confounders, including sociodemographic factors, health and functional status, medical comorbidity, and index hospitalization-related characteristics. The independent association of early readmission with limited survival provides a marker of very high-risk patients, in whom the complex range of biopsychosocial factors that likely contribute to hospital readmission also put patients at risk for mortality. Although we do not yet know if preventing readmissions increases survival, recognizing the dire associations of early readmission should propel healthcare providers to reconsider any readmitted patient’s overall prognosis and reevaluate goals of care and treatment plans. Given our findings of an association between early readmission and substantially increased one-year mortality, validation of these results in another study and potentially incorporating early readmission status into future risk indices for older adults would be appropriate.

In addition to the striking predictive value of early readmission, we identified several baseline characteristics also associated with increased mortality. Our findings are consistent with other studies that found mobility difficulty measured by gait speed16 and poor self-rated health17 to be associated with limited survival in older adults. Similarly, our results confirm research demonstrating that in elderly cohorts, being underweight increased mortality and being overweight was protective.18,19 Comorbid cancer, chronic lung disease, and renal failure were also associated with higher mortality rates.

In focusing on the large group of community-dwelling elders especially relevant to clinical and policy dilemmas, we found an early readmission rate of 13.7 % in our cohort of Medicare beneficiaries that is lower than the 19.6 % 30-day readmission rate reported by Jencks et al.1 Our lower readmission rate is likely explained by our exclusion of Medicare beneficiaries with the highest readmission rates, as well as healthy volunteer and survivor bias inherent in our cohort construction. We excluded beneficiaries younger than 65 (16 % of the MCBS participants); these younger disabled beneficiaries had a higher readmission rate (17.0 %) than community-dwelling older beneficiaries. We also excluded institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries (6 % of MCBS participants) because factors influencing their readmissions and potential interventions likely differ from adults in the community.6 Finally, we did not exclude “elective readmissions,” which are estimated to be about 10 % of hospital readmissions; these patients are probably less likely to die than those who are urgently readmitted. Healthy volunteer bias and survivor effects further reduced our cohort’s early readmission rate; our study could not include persons who were too sick to enroll in the MCBS at all, who died before the baseline interview in the second year or during the index hospitalization, or who were discharged with hospice care. Although the direct implication of our findings to the individual Medicare patient requires further work, the relatively low rate of early readmissions resulting from the exclusion of so many of the sickest Medicare beneficiaries makes the strong association of early readmission with one-year mortality in this older, community-dwelling, comparatively healthier group all the more remarkable.

In the most practical terms, the association of early readmission with mortality reveals an easily identified and clinically significant opportunity to review treatment goals and plans. Hospital readmission could trigger discussions among the patient, family, and health care providers about current treatments, quality of life, need and provisions for home support, and overall goals of care in the setting of progressive or terminal disease. Research has connected some readmissions with potentially modifiable factors,4,6,20—such as lack of patient education on discharge, unmet functional needs, and poor access to care—to which physicians treating readmitted patients should devote particular attention. Several multi-disciplinary discharge interventions to prevent hospital readmissions have been developed,21–23 and our data support additional efforts oriented specifically toward the community-dwelling geriatric population. Looking beyond the scope of this study, future research should investigate potential causes of recurrent hospitalization, such as worsening medical condition, inadequate discharge resources, or deteriorating functional status.

Our study has some notable limitations. Although the baseline interview provided thorough information about beneficiaries’ characteristics, we lack data about later changes in health and functional status or medical conditions. Therefore, we cannot identity risk factors related to acute problems that may have prompted either the index hospitalization or readmission. The use of administrative data to characterize the hospitalizations prevents us from determining disease severity directly, although we have included markers for disease severity such as receiving intensive care and length of stay. Additionally, our sample of readmitted patients was too small to identify risk factors for mortality specifically among readmitted patients. From a clinical perspective, proper allocation of energy and resources requires identifying those readmitted patients at highest risk for early morbidity and mortality.

In conclusion, the one-year mortality of community-dwelling older adults following early hospital readmission approaches 40 %. Early readmission is a strong and independent risk factor for early mortality after hospitalization. Above all, our findings suggest that early hospital readmission indicates extreme vulnerability among elderly patients. Heightened awareness of the association of early readmission with mortality might lead to opportunities for modifying risk factors and better evaluating overall prognosis.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Robert Arnold, MD, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh for critical review. Grant support from AG032291 and the Pittsburgh Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30 AG024827), National Institute on Aging. Dr Hardy receives support from a Beeson Career Development Award (AG030977). This paper was presented at the American Geriatrics Society 2010 Annual Scientific Meeting, May 13, 2010.

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Lum, Degenholtz, and Hardy declare that they do not have a conflict of interest. Dr. Studenski has consulted for Merck, Novartis, and GTX, received grant funding from Merck, and received textbook royalties from McGraw Hill.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, et al. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):211–219. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walraven C, Dhalla IA, Bell C, et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ. 2010;182(6):551–557. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcantonio ER, McKean S, Goldfinger M, Kleefield S, Yurkofsky M, Brennan TA. Factors associated with unplanned hospital readmission among patients 65years of age and older in a Medicare managed care plan. Am J Med. 1999;107(1):13–17. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00159-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed RL, Pearlman RA, Buchner DM. Risk factors for early unplanned hospital readmission in the elderly. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6(3):223–228. doi: 10.1007/BF02598964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverstein MD, Qin H, Mercer SQ, Fong J, Haydar Z. Risk factors for 30-day hospital readmission in patients >/=65 years of age. Bayl Univ Med Cent Proc. 2008;21(4):363–372. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2008.11928429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1371–1386. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bravata DM, Ho SY, Meehan TP, Brass LM, Concato J. Readmission and death after hospitalization for acute ischemic stroke: 5-year follow-up in the medicare population. Stroke. 2007;38(6):1899–1904. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.481465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bahadori K, FitzGerald JM, Levy RD, Fera T, Swiston J. Risk factors and outcomes associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations requiring hospitalization. Can Respir J. 2009;16(4):e43–e49. doi: 10.1155/2009/179263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walter LC, Brand RJ, Counsell SR, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 1-year mortality in older adults after hospitalization. JAMA. 2001;285(23):2987–2994. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Technical Documentation for the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Data Tables. 2003.

- 13.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris D, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Palmer L. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS), 2012. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp Accessed on May 12, 2012.

- 15.Ciol MA, Hoffman JM, Dudgeon BJ, Shumway-Cook A, Yorkston KM, Chan L. Understanding the use of weights in the analysis of data from multistage surveys. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(2):299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, et al. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305(1):50–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SJ, Moody-Ayers SY, Landefeld CS, et al. The relationship between self-rated health and mortality in older black and white Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(10):1624–1629. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landi F, Onder G, Gambassi G, Pedone C, Carbonin P, Bernabei R. Body mass index and mortality among hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(17):2641–2644. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McAuley P, Pittsley J, Myers J, Abella J, Froelicher VF. Fitness and fatness as mortality predictors in healthy older men: the veterans exercise testing study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(6):695–699. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arbaje AI, Wolff JL, Yu Q, Powe NR, Anderson GF, Boult C. Postdischarge environmental and socioeconomic factors and the likelihood of early hospital readmission among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):495–504. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koehler BE, Richter KM, Youngblood L, et al. Reduction of 30-day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):211–218. doi: 10.1002/jhm.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613–620. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.