The Trajectory of Depressive Symptoms Across the Adult Lifespan (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2014 Feb 1.

Abstract

Context

Long-term longitudinal studies are needed to delineate the trajectory of depressive symptoms across adulthood and to individuate factors that may contribute to increases in depressive symptoms in older adulthood.

Objective

(1) To estimate the trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adult lifespan, (2) to test whether this trajectory varies by demographic factors (sex, ethnicity, education) and antidepressant medication use, and (3) to test whether disease burden, functional limitations, and proximity to death explain the increase in depressive symptoms in old age.

Design

Longitudinal study

Setting

Community

Participants

2,320 participants (47% female; mean age at baseline=58.10 years, _SD_=17.05; range 19–95 years) from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging

Main Outcome Measure

Estimated trajectory of depressive symptoms modeled from 10,982 assessments (M assessments per participant=4.73, _SD_=3.63, range=1–21) of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale and three subscales (depressed affect, somatic complaints, and interpersonal problems).

Results

Both the linear (γ10=.52, p<.01) and quadratic (γ20=.43, p<.01) terms were significant, which indicated that depressive symptoms were highest in young adulthood, decreased across middle adulthood, and increased again in older adulthood. The subscales followed a similar pattern. Women reported more depressed affect at younger ages, but an interaction with age suggested that this gap disappeared in old age. Accounting for comorbidity, functional limitations, and impending death slightly reduced, but did not eliminate, the uptick in depressive symptoms in old age.

Conclusions

Symptoms of depression follow a U-shaped pattern across adulthood. Older adults experience an increase in distress that is not due solely to declines in physical health or approaching death.

Depression is a common mental disorder that is among the leading causes of disability worldwide1,2. The burden of depression and depressive symptoms is pervasive and varied, ranging from decreased socio-emotional well-being3 to impaired physical health2 to lower productivity in the workplace4. Given that depressive symptoms are associated with important life outcomes at every stage of life, there has been great interest in understanding the trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adulthood.

Epidemiological evidence suggests that the prevalence of major depressive disorder declines with age5. In contrast, depressive symptoms, after a mid-life decline, may increase again at older ages6–8. Longitudinal studies of depressive symptoms, however, have focused primarily on one segment of the adult lifespan9,10 or on transition points (e.g., from adolescence to young adulthood11). Repeated assessments over a substantial period of time are needed to reliably estimate the trajectory of depressive symptoms across adulthood. In addition, it is likely that not everyone is changing in the same way. Previous research suggests that mean-levels of depressive symptoms differ by sex12,13, ethnicity14, and education15,16, but it is less clear whether these differences increase or decrease over time7,16,17,18,19,20.

Depressive symptoms in older adulthood are linked to a number of consequential outcomes, including decreased quality of life21, greater disease burden22, less ability to cope with illness23, and premature mortality23. If there is an increase in depressive symptoms in older age, it is important to determine whether it is due primarily to declines in physical health. Although those suffering from chronic diseases8 and functional limitations24 are more prone to experiencing depressive symptoms, such burdens may not fully explain the increase in old age8. Further, neuroticism (i.e., a general tendency to experience negative affect) tends to increase and well-being (e.g., life satisfaction, happiness) tends to decline sharply with impending death25. Thus, the uptick in depressive symptoms in old age may be due to end-of-life factors related to deteriorating health and/or proximity to death.

The present research uses more than 30 years of depressive symptom assessments from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). With >10,000 repeated assessments of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) over 30 years (M assessments per participant = 4.73, SD = 3.63, range = 1 to 21), we examine the trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adult lifespan. In addition to the CES-D total scale score, we examine three subscales that tap into different types of depressive symptoms: depressed affect, somatic complaints, and interpersonal problems. These aspects of depressive symptoms may not necessarily follow the same trajectory over the lifespan. It is particularly important to separate the somatic aspects from other types of symptoms, as such items may also reflect changes in physical health that are more prevalent with aging26. We also examine differences in this trajectory across demographic characteristics (sex, ethnicity, education) and the use of antidepressant medication27. Finally, we test whether increases in depressive symptoms in old age could be accounted for by disease burden, functional limitations, and proximity to death.

Method

Participants and procedure

A total of 2,320 community-dwelling volunteers from the BLSA participated in the study. Started in 1958, the BLSA is an ongoing multidisciplinary study of aging administered by the National Institute on Aging. This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed consent. The current sample is 47% female, 73.4% White, 20.0% Black, and 6.6% other ethnicities (all self-reported), and educated (M = 16.46 years of education, SD = 2.42). The CES-D assessment started in 1979; data used in the present study were collected between January 1979 and December 2011 at regularly scheduled visits. As of 2011, attrition was ~15%. After controlling for age, sex, ethnicity, and education, there were no differences in the total CES-D score or the subscales between participants who dropped out versus stayed in the study (see Supplementary Material for detailed attrition analyses).

The mean age at the first CES-D assessment was 58.10 years (SD = 17.05; range 19 to 95 years) and the mean age at the most recent assessment was 69.96 years (SD = 15.86; range 24 to 101 years). Participants completed up to 21 assessments of the CES-D (M assessments per participant = 4.73, SD = 3.63, range = 1 to 21) for a total of 10,982 assessments of depressive symptoms across more than 30 years. The mean interval between administrations was 2.67 years (SD = 2.23; range 4 months to 21 years; Table 1). Morbidity analyses (described below) focus on a subset of participants 60 years and older (_n_=1482; _M_age=74.69, _SD_=8.60; 43% female). See Supplementary Material for additional information about the BLSA.

Table 1.

Average follow-up and number of assessments by baseline age

| Age at baseline | % | Average interval between assessments | Average total follow-up | Average number of assessments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | 7.2 | 2.49 (1.09) | 9.09 (7.36) | 2.87 (1.62) |

| 30–39 | 8.9 | 3.56 (2.48) | 9.63 (8.18) | 3.18 (2.30) |

| 40–49 | 17.9 | 3.84 (3.34) | 12.20 (6.78) | 4.51 (2.60) |

| 50–59 | 15.9 | 3.58 (2.62) | 12.31 (7.06) | 5.59 (3.81) |

| 60–69 | 20.4 | 2.72 (2.00) | 12.19 (7.21) | 6.56 (4.41) |

| 70–79 | 19.3 | 2.41 (1.86) | 7.12 (6.25) | 4.43 (3.81) |

| 80–89 | 9.8 | 1.95 (1.64) | 4.48 (4.49) | 3.51 (2.86) |

| 90+ | .6 | 1.99 (2.35) | 1.48 (1.55) | 2.00 (1.16) |

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)28. This 20-item scale assesses the frequency of a variety of depressive symptoms within the previous week. Items are rated on a four-point scale from 0 (rarely) to 3 (most or all of the time). A score of 16 is typically considered the threshold for severe depressive symptoms 29. In addition to the total scale score, we examined three subscales that tap into different aspects of depressive symptoms28, 30: Depressed Affect (7 items; e.g., “I felt sad.”), Somatic Complaints (7 items; e.g., “My sleep was restless.”), and Interpersonal Problems (2 items; e.g., “I felt that people disliked me.”). At baseline, the total CES-D had a mean of 7.05 (SD = 6.92; range 0–50), Depressed Affect had a mean of 1.57 (SD = 2.67; range 0–20), Somatic Complaints had a mean of 3.12 (SD = 2.94; 0–20) and Interpersonal Problems had a mean of .24 (SD = .68; range 0–6).

Antidepressant medication

Information on antidepressant medication use was available for the majority of visits (_n_=10,442). Participants reported using antidepressant medication at approximately 8% of these visits (826 visits, _n_=404).

Illness burden

Illness burden was assessed with the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)31. The CCI is the weighted sum of 19 clinical conditions found to increase risk of mortality, including myocardial infarct, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, dementia, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, connective tissue disease, ulcer disease, mild liver disease, diabetes, hemiplegia, moderate or severe renal disease, diabetes with end organ damage, any tumor, leukemia, lymphoma, moderate or severe liver disease, metastatic solid tumor, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. We used an adapted version of the CCI, which defines each condition by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes and combines leukemia and lymphoma with any tumor32. This version has been found to consistently predict mortality33, 34. We calculated the CCI from the medical history administered by a certified nurse practitioner at each visit. For the morbidity analyses, we focus on participants that were 60 years and older at the time of assessment (_n_=1,482). The CCI was available at 6,523 concurrent visits with the CES-D. The CCI had a mean of .74 (SD = 1.07, range 0 to 8 diseases) at the first assessment and a mean of 1.48 (SD = 1.49, range 0 to 10 diseases) at the most recent assessment.

Functional limitations

Difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs35; e.g., bathing) and difficulties with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs36; e.g., meal preparation) were available for a subset of participants 60 years and older (_n_=972) and visits (2,286 visits). At the first assessment, ADLs had a mean of .13 (SD=.53, range 0 to 5 limitations) and IADLs had a mean of .18 (_SD_=.63, range 0 to 7 limitations). At the most recent assessment, ADLs had a mean of .25 (_SD_=.82, range 0 to 5 limitations) and IADLs had a mean of .29 (_SD_=.86, range 0 to 7).

Statistical overview

We used Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM)37, 38 to estimate the trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adult lifespan. HLM is a flexible approach that can be applied to evaluate within-individual change or growth trajectories. In HLM analyses, the number and spacing of measurement observations may vary across persons, given that the time-series observations in each individual are used to estimate each individual’s trajectory (Level 1), and those individual parameters are the basis of group estimates (Level 2). Even data from individuals who were tested on only a single occasion can be used to stabilize estimates of the mean and variance. In this way, all available data can be included in the analyses. This is a major advantage of conducting analyses within the HLM framework; by contrast, missing data and varying timing pose major problems in conventional repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA)39. Furthermore, longitudinal HLM can estimate age trajectories over a broad age span with data collected in a relatively shorter time interval.

We conducted the analyses using HLM Version 640. To evaluate the longitudinal trajectories, we first defined the Level 1 model and then tested possible Level 2 predictors. At Level 1, we fit a quadratic model for the total CES-D score and separately for each subscale to test for potential non-linear changes in depressive symptoms across the lifespan41, 42. At Level 2, we entered characteristics of the individual (sex, ethnicity, and education) as independent variables to explain between-subjects variation in the intercept and linear and quadratic slopes. We centered age in decades on the grand mean (66.39 years) to minimize the correlation between the linear and quadratic terms. Antidepressant medication use, illness burden, and functional limitations were entered at Level 1 as time-varying covariates to test their effect on the trajectory of depressive symptoms.

Results

Trajectory of Depressive Symptoms

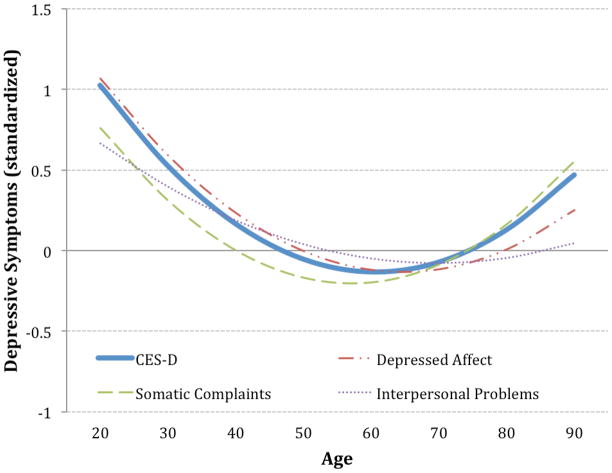

The estimates for the trajectory of depressive symptoms across adulthood are shown in Table 2 (Table S1 shows the deviance statistics for all models). As depicted in Figure 1, depressive symptoms were the highest in early adulthood, declined in middle adulthood, and then increased in older adulthood (Figure S1 shows the scales in the raw metric and Figure S2 shows spaghetti plots of the raw data). The intercept indicated that, at about age 66, participants scored approximately 5.78 on the CES-D. At the subscale level, depressed affect and interpersonal problems followed a similar trajectory to that of the total CES-D. Somatic complaints also followed a similar trajectory, but increased slightly more in older adulthood. The intercept, linear, and quadratic slope estimates were similar when controlling for sex, ethnicity, education, antidepressant medication use, disease burden, and functional limitations (Table S2).

Table 2.

HLM Coefficients and Variance Estimates of Intercept, Linear, and Quadratic Equations Predicting Depressive Symptoms from Age and Age Squared in Decades

| Scale | Intercept | Slope | Quadratic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ00: Mean | u0:Variance | γ 10: Mean | u1:Variance | γ20: Mean | |

| CES-D | 5.78 (.11)** | 13.93** | .52 (.07)** | 3.18** | .43 (.03)** |

| Depressed Affect | 1.13 (.04)** | 1.32** | .05 (.02)* | .50** | .15 (.01)** |

| Somatic | 2.89 (.05)** | 2.99** | .39 (.03)** | .43** | .20 (.01)** |

| Interpersonal | .17 (.01)** | .05** | −.01 (.01) | .02** | .02 (.00)** |

| CESD-16 items | 4.18 (.09)** | 7.82** | .43 (.05)** | 1.90** | .38 (.02)** |

Figure 1.

Estimated trajectory of the CES-D total scale score and the three subscales across adulthood. Raw scored were z-transformed so that all scales could be plotted on the same axis. Supplemental Figure 1 shows the estimated trajectories of each scale in the original metric.

Predictors of the Trajectory of Depressive Symptoms

Demographics

We first tested the effect of sex, education, and ethnicity on the intercept and slopes of the CES-D and the subscales (Table 3). There was no effect of sex on the intercept of the CES-D, which indicated that men and women experienced depressive symptoms to a similar extent. The subscales, however, revealed that women reported more depressed affect than did men. We previously reported that women in the BLSA also tended to report greater well-being44, which when combined with the negative affect items in the total scale score obscured the association with total depressive symptoms. And indeed, in the present study, when the four positively-valenced items were removed from the total scale score, women had significantly more depressive symptoms than men (β=.43, SE=.18; p<.01).

Table 3.

Effect of Demographic Factors, Antidepressant Medication Use, Disease Burden and Death on the Intercept and Slopes of Depressive Symptoms

| Factor | Intercept | Slope | Quadratic | Intercept | Slope | Quadratic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D | Depressed Affect | |||||

| Sex (Female) a | −.02 (.23) | −.23 (.15) | .04 (.06) | .27 (.08)** | −.11 (.05)* | .01 (.02) |

| Ethnicity (Black)a | −.33 (.30) | .31 (.22) | −.14 (.09) | −.04 (.10) | −.06 (.08) | −.05 (.03) |

| Ethnicity (Other)a | −.32 (.50) | −.50 (.37) | −.29 (.15) | .00 (.18) | −.10 (.14) | −.11 (.06) |

| Educationa | −.13 (.04)* | −.03 (.03) | −.02 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | .00 (.00) |

| Medicationb,c | .84 (.39)** | −.32 (.14)* | .06 (.07) | .34 (.11)** | −.08 (.05) | .06 (.03)* |

| Disease Burdenb,d | .33 (.12)** | −.09 (.19) | .03 (.10) | .10 (.04)* | −.12 (.07) | .06 (.03)* |

| ADLsb,e | 1.08 (.53)* | −.20 (.25) | -- | .42 (.21)* | −.03 (.10) | -- |

| IADLsb,e | 1.68 (.44)** | −.46 (.20)* | -- | .46 (.18)* | −.08 (.08) | -- |

| Deatha | 1.44 (.28)** | .08 (.22) | .16 (.10) | .04 (.10) | .06 (.09) | .07 (.04) |

| Somatic Complaints | Interpersonal Problems | |||||

| Sex (Female) a | .20 (.11) | −.05 (.06) | .01 (.03) | −.02 (.02) | −.01 (.01) | .00 (.00) |

| Ethnicity (Black)a | .20 (.14) | −.15 (.10) | −.08 (.04)* | .05 (.02)* | .01 (.02) | .00 (.01) |

| Ethnicity (Other)a | .05 (.21) | −.15 (.16) | −.13 (.05)* | .09 (.04)* | −.02 (.03) | −.03 (.01)* |

| Educationa | −.04 (.02)* | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.01) | −.01 (.00)* | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) |

| Medicationb,c | .61 (.13)** | −.18 (.07)** | −.03 (.03) | −.03 (.03) | .00 (.02) | .02 (.01)* |

| Disease Burdenb,d | .20 (.05)** | .03 (.08) | −.03 (.04) | .01 (.01) | .02 (.02) | −.01 (.01) |

| ADLsb,e | .65 (.27)* | −.18 (.13) | -- | .04 (.06) | .00 (.03) | -- |

| IADLsb,e | .97 (.22)** | −.31 (.10)** | -- | .07 (.06) | .01 (.03) | -- |

| Deatha | −.13 (.13) | .17 (.10) | .10 (.04)* | −.03 (.02) | .04 (.02) | .00 (.01) |

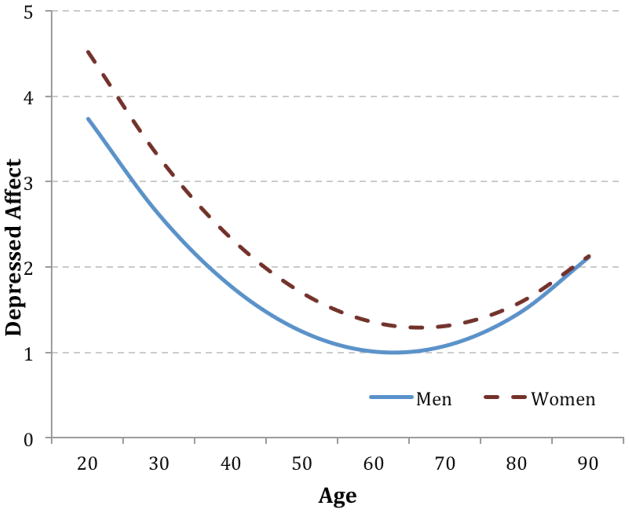

There was also a significant effect of sex on the slope of depressed affect (Figure 2). This interaction with age indicated that women experienced more negative affect in early adulthood, but men increased more in older adulthood. The trajectories of men and women converged by old age, such that after about age 70 there were no longer differences in depressed affect between the sexes. There was no effect of sex on the slopes of the other two subscales.

Figure 2.

Estimated trajectory of depressed affect by sex.

Modest effects emerged for education and ethnicity. Education was associated with fewer symptoms of depression, particularly somatic complaints and interpersonal problems. African Americans and participants of other ethnicities had slightly higher mean levels of interpersonal problems, but participants of other ethnicities increased less on Interpersonal Problems into older age. Finally, African Americans and participants of other ethnicities did not increase as much in Somatic Complaints in older age compared to white participants (Table 3).

Antidepressant use

Not surprisingly, antidepressant medication use was associated with both the intercept and trajectory of depressive symptoms (Table 3). Participants who took antidepressants reported more depressive symptoms than participants who did not take medication and they declined less in depressive symptoms across adulthood. The association of antidepressant use and the three subscales was similar to the overall CES-D. As a supplementary analysis, we re-ran all models excluding participants who had ever reported taking antidepressant medication. The estimates were virtually identical to those on the entire sample. We also tested if there was a difference in the trajectory of those who had ever experienced severe depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥16; _n_=570) at any point in the study. And, indeed, these participants had an amplified curve compared to those who had not experienced severe depressive symptoms. That is, these participants reported more depressive symptoms in early adulthood, they had a steeper decline across middle adulthood, and a steeper increase in old age (Figure S3).

Morbidity

We next tested whether disease burden or functional limitations could account for the uptick in depressive symptoms in old age (Table 3). Morbidity was primarily associated with the intercept of depressive symptoms: participants with greater disease burden and more functional limitations reported more depressive symptoms, particularly Depressed Affect and Somatic Complaints than those with less morbidity. Disease burden was also associated with a greater increase in Depressed Affect in old age. IADLs had a negative effect on the slope of the total CES-D and Somatic Complaints such that participants with more limitations increased less in depressive symptoms as they aged. This effect was driven by the effect of IADLs on the intercept. That is, those with functional limitations reported more depressive symptoms, but over time those who did not report IADLs increased significantly more in depressive symptoms that they caught up to those reporting IADLs (Figure S4). Due to the reduced sample size and assessments of ADLs/IADLs, there was not enough power to test whether functional limitations were associated with the quadratic slope of depressive symptoms. Of note, accounting for disease burden and functional limitations did not eliminate the increase in depressive symptoms in old age (Table S2).

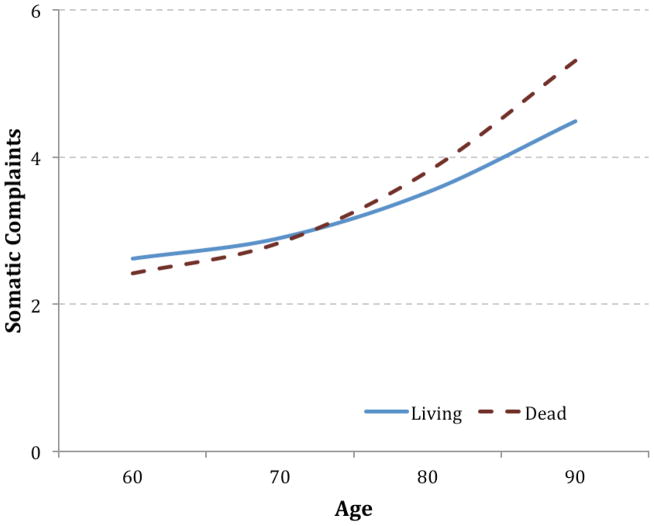

Mortality

We tested the effect of mortality on the trajectory of depressive symptoms in several ways. First, we entered a dummy-coded variable into the model that contrasted participants who died during the study with participants who were still living at the time of analysis as a Level 2 predictor of the intercept and slope (Table 3). For the overall scale score, death was associated with a higher intercept but was unrelated to the slopes. The opposite pattern, however, emerged for Somatic Complaints: death was unrelated to the intercept of Somatic Complaints, but it predicted a steeper slope at older ages (Figure 3). Death was unrelated to interpersonal problems and depressed affect. Of note, the increase in depressive symptoms in late life remained after accounting for death (Table S2).

Figure 3.

Estimated trajectory of somatic complaints in old age by participants still living and participants who died.

Second, we re-ran the HLM analyses after excluding all CES-D assessments within five years of death. The linear slope estimates were slightly smaller, but the pattern of estimates was virtually identical to that of the total sample (Table S2).

Third, we tested whether there was a terminal increase in depressive symptoms with proximity to death. We re-analyzed the data from participants who had died (_n_=728) during the course of the study using time to death as the metric rather than time since birth (i.e., chronological age)45. We controlled for sex, ethnicity, education, and included age at each assessment as a time-varying covariate. In this case, the intercept represents the estimated depressive symptoms at the time of death and the slope represents the estimated change in depressive symptoms every year before death. Thus, a negative slope indicates an increase in depressive symptoms for every year approaching death (i.e., each successive year before death had fewer depressive symptoms). The linear slope of the CES-D and two of the three subscales (depressed affect, somatic complaints) were significant, which indicated an increase in depressive symptoms with approaching death (Table 4). The quadratic slope of the CES-D was also significant, but this was due to the positively-worded items. The quadratic slope was not significant for any of the subscales, nor was it significant for the CES-D total score without the positively-valenced items (π2=.00 [SE=.00], ns). These results suggested that although there was an increase in depressive symptoms with approaching death, the increase was not exponential.

Table 4.

HLM Coefficients and Variance Estimates of Intercept, Linear, and Quadratic Equations Predicting Depressive Symptoms Using Distance to Death (in years) as the Time Metric

| Scale | Intercept | Slope | Quadratic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ00: Mean | u0:Variance | γ10: Mean | u1:Variance | γ20: Mean | |

| CES-D | 8.68 (.65)** | 39.74** | −.40 (.07)** | .12** | .02 (.00)** |

| Depressed Affect | 1.55 (.23)** | 4.48** | −.07 (.03)* | .01** | .00 (.00) |

| Somatic | 3.62 (.29)** | 7.42** | −.10 (.03)** | .02** | .00 (.00) |

| Interpersonal | .17 (.05)** | .13** | .00 (.00) | .00** | .00 (.00) |

To put the effect of death into context, we examined the corresponding change in depressive symptoms for long-lived participants. We selected participants aged 90 or older at their last CES-D assessment (_n_=59) and estimated their trajectory. The average age of death among the dead was 85, so we compared the increase in depressive symptoms across the last decade of life with the increase in depressive symptoms among the long-lived participants between ages 75 and 85. From the estimates from the distance to death analysis, participants increased by about 2.00 points in depressive symptoms in the decade before they died. By comparison, the long-lived participants increased about 1.89 points between ages 75 and 85. Somatic complaints, which might be expected to increase the most prior to death, increased by about one point in the last decade of life, whereas it increased by 1.70 points in the long-lived group. Thus, although there appears to be an increase in depressive symptoms with the approach of death, the increase is roughly similar to the increase seen with age among the most long-lived (and thus presumably healthier) participants.

Discussion

Using repeated assessments of the CES-D over a period of 30 years, we estimated the trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adult lifespan. At about age 66, participants scored approximately 5.78 on the CES-D, which is in the range of other large samples of similar age (e.g., the mean CES-D score was 5.81 at a mean age of about 65 in the Rotterdam Study)43. Significant linear and quadratic slopes indicated that symptoms of depression tend to be highest in young adulthood, decrease across middle adulthood, and increase again in older age, with the most prominent change seen for those who had ever experienced severe depressive symptoms. Individual differences in the slopes of the trajectories suggested that not everyone is changing in the same way. The use of antidepressant medication had the largest association with the slope of depressive symptoms; the effects of the demographic factors, disease burden, and functional limitations were small to moderate by comparison. Finally, disease burden, functional limitations, and impending death explained only part the increase in depressive symptoms in older adulthood.

Psychological health across the lifespan has been addressed in several ways, including age-related changes in the prevalence of major depression and other mood disorders, assessments of depressive symptoms, and various indices of well-being. Large-scale studies have consistently documented declines in the 12-month prevalence of mood disorders across adulthood, including a further decline in older age46,47,48. Consistent with smaller studies, our findings parallel these age trends until older adulthood, when, starting in about the seventh decade of life, depressive symptoms begin to rise. This uptick toward the end of life differs from age-related changes in prevalence, but the increase in old age is similar to smaller longitudinal studies of depressive symptoms limited to older adulthood10,8, studies of subthreshold depression49, as well as the trajectory of related constructs, such as Neuroticism50,51. In the current study, the increase in depressive symptoms toward the end of life was relatively modest, with an estimated average increase of 1.37 points in the total CES-D scale score per decade between the ages of 60 and 90. In contrast to clinical mood disorders, the increase in depressive symptoms in old age may be a general phenomenon that tends to occur across a broad segment of the population, not just in a minority of cases that cross the clinical threshold. Thus, although the prevalence of extreme depressive symptoms may decline, the mean number of depressive symptoms in the population may increase.

Symptoms of depression tend to be higher among women12,13, ethnic minorities14,19,20, and those with lower education15,16. Our findings generally mirror these mean-level trends, except that, because women reported higher well-being as well as higher depressed affect, sex was unrelated to the intercept of the CES-D total scale score. With age, there may17 or may not7,8 be sex differences in the trajectory of depressive symptoms. We found support for both positions: sex was associated with the slope of depressed affect, but not with any other symptoms of depression. The convergence between men and women in older age was mainly due to a steeper increase in symptoms reported by men starting in their mid 60s.

In charting the trajectory of depressive symptoms into old age, it is important to distinguish between somatic and non-somatic aspects of depressive symptoms. Of note, our analysis at the subscale level indicated that the uptick in the total CES-D score in older adulthood was not exclusively due to items related to somatic problems. In addition to the increase in somatic complaints, which may be due, in part, to declines in physical health, older age was also associated with an increase in depressed affect. Although pain and other physical conditions increase substantially with age, the co-morbidity between depression and physical ailment may not47. Functional limitations may be associated with increases in depressive symptoms, but declines in physical health with aging do not account for all of the increases in depressive symptoms8,47. Similarly, in the present study, neither disease burden nor functional limitations could completely explain the increase in depressive symptoms at older ages. More detailed assessments of physical functioning, however, are needed before ruling out that the increase in depressive symptoms with age is not due solely to declines in physical health.

In addition to disease burden, proximity to death may partially contribute to the end-of-life increase in depressive symptoms. Previous research has found that well-being declines exponentially with impending death52,25; there may be a corresponding increase in depressive symptoms. We found partial support for this hypothesis. There was a small increase in depressive symptoms with approaching death using either age or distance to death as the time metric. There was not, however, any evidence of an exponential increase in depressive symptoms and the increase was comparable to that of age-related changes estimated from the most long-lived participants in the sample. Taken together, previous research on well-being and the current study on depressive symptoms suggest that as death approaches, individuals may become less happy rather than experience more sadness. And, similar to disease burden and functional limitations, impending death did not fully account for all of the increase in depressive symptoms in old age.

Other factors, besides those tested in this study, may contribute to the rise of depressive symptoms in older age. With age comes loss, and the loss of loved ones53, deteriorating social support networks10, 54, and loss of employment53 and income55 can all contribute to increases in depressive symptoms. Psychological factors, such as changes in time perspective10, feelings of obsolescence and loss of personal control53, as well as changes in coping styles and beliefs10 may also contribute to the increase in depressive symptoms toward the end of life. Thus, life circumstances and psychological processes may explain the increase in depressive symptoms in old age that is not accounted for by deteriorating physical health.

This study had several strengths, including a large sample with over 30 years of assessments of one of the most commonly used measures of depressive symptoms in epidemiology across a broad age range. Despite these strengths, some limitations should be considered. For example, our sample was more educated than the general population. Our findings, however, were broadly consistent with cross-sectional studies of age-related changes in depressive symptoms7. In addition, our analyses of impending death might be limited in two ways. First, because participants suffering from a terminal illness may have missed assessments because they were too sick to continue participation in the study, we may have missed a critical time period before death. Second, because our sample was fairly privileged, participants may have remained healthier longer, enduring a relatively shorter decline towards death. Thus, the increase in depressive symptoms with impending death may have been more modest than in more representative samples.

Despite these limitations, the present research provides useful information on changes in depressive symptoms across the adult lifespan. The overall trajectory was consistent with the clinical literature until older adulthood, which suggests that older adults are susceptible to increased distress. These seemingly modest effects are nonetheless clinically meaningful. Previous research on subthreshold depression, for example, has suggested that scoring just 6 points on the CES-D is associated with a significant increase in functional limitations 3–4 years later 56 and with more disability days and lower self-rated health and social support57. Mild depressive symptoms have also been associated with slower physical and cognitive functioning58. Thus, seemingly modest depressive symptoms may thus have a significant impact on many aspects of an individual’s life in older adulthood. The divergence with clinical depression and the effect of even modest depressive symptoms on physical and cognitive functioning underscore the importance of assessing distress that does not pass a clinical threshold.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging.

Role of the funder: The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or the decision to submit.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Dr. Sutin had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Sutin performed the statistical analysis for this study.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1436–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: Results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:851–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coryell W, Scheftner W, Keller M, Endicott J, Maser J, Klerman GL. The enduring psychosocial consequences of mania and depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:720–727. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, Leong SA, Lowe SW, Berglund PA, Corey-Lisle PK. The economic burden of depression in the United States: How did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1465–1475. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Bromet E, Hwang I, Sampson N, Shahly V. Age differences in major depression: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R) Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):225–237. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blazer DG, Landerman LR, Hays JC, Simonsick EM, Saunders WB. Symptoms of depression among community-dwelling elderly African-American and White older adults. Psycho Med. 1998;28(6):1311–1320. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, Foster C, Webster PS, House JS. The relationship between age and depressive symptoms in two national surveys. Psychol Aging. 1992;7:119–126. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiske A, Gatz M, Pedersen NL. Depressive symptoms and aging: The effects of illness and non-health-related events. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58:P320–P328. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.p320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Needham BL, Epel ES, Adler NE, Kiefe C. Trajectories of change in obesity and symptoms of depression: The cardia study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1040–1046. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.172809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothermund K, Brandtstädter J. Depression in later life: Cross-sequential patterns and possible determinants. Psychol Aging. 2003;18:80–90. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Angell KE, Silva PA, McGee R. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van de Velde S, Bracke P, Levecque K, Meuleman B. Gender differences in depression in 25 European countries after eliminating measurement bias in the CES-D 8. Soc Sci Res. 2010;39:396–404. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bromberger JT, Harlow S, Avis N, Kravitz HM, Cordal A. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of depressive symptoms among middle-aged women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1378–1385. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Durden E. Socioeconomic status and age trajectories of health. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:2489–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miech RA, Shanahan MJ. Socioeconomic status and depression over the life course. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41:162–176. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barefoot JC, Mortensen EL, Helms MJ, Avlund K, Schroll M. A longitudinal study of gender differences in depressive symptoms from age 50 to 80. Psychol Aging. 2001;16:342–345. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skarupski KA, Mendes De Leon CF, Bienias JL, Barnes LL, Everson-Rose SA, Wilson RS, Evans DA. Black-white differences in depressive symptoms among older adults over time. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:P136–P142. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.3.p136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsemann KM, Gee GC, Geronimus AT. Ethnic differences in trajectories of depressive symptoms: Disadvantage in family background, high school experiences, and adult characteristics. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50:82–98. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu X, Liang J, Bennett JM, Quiñones AR, Ye W. Ethnic differences in the dynamics of depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older Americans. J AgingHealth. 2011;22:631–652. doi: 10.1177/0898264310370851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wella KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, Berry S, Greenfield S, Ware J. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the medical outcomes study. J Am Med Assoc. 1989;262:914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katon W, Lin EHB, Kroenke K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Talajic M. Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;91:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunne E, Wrosch C, Miller GE. Goal disengagement, functional disability, and depressive symptoms in old age. Health Psychol. 2012;30:763–770. doi: 10.1037/a0024019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerstorf D, Ram N, Mayraz G, Hidajat M, Lindenberger U, Wagner GG, Schupp J. Late-life decline in well-being across adulthood in germany, the united kingdom, and the united states: Something is seriously wrong at the end of life. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:477–485. doi: 10.1037/a0017543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fonda SJ, Herzog AR. Patterns and risk factors of change in somatic and mood symptoms among older adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:361–368. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan A, Brodhead AE, Kolts RL, Brown WA. Severity of depressive symptoms and response to antidepressants and placebo in antidepressant trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measures. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ, Van Tilburg W. Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): Results from a community-based sample of older subjects in the Netherlands. Psychol Med. 1997;27(1):231–235. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hertzog C, Van Alstine J, Usala PD, Hultsch DF, Dixon R. Measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in older populations. Psychol Assess. 1990;2:64–72. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KA, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Avorn J, Maclure M, Levin R, Glynn RJ. Consistency of performance ranking of comorbidity adjustment scores in Canadian and U.S. utilization data. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:444–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan Y, Birman-Deych E, Radford MJ, Nilasena DS, Gage BF. Comorbidity indices to predict mortality from medicare data: Results from the national registry of atrial fibrillation. Med Care. 2005;43:1073–1077. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182477.29129.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure if biological and psychosocial function. J Am Med Assoc. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gueorguieva R, Krystal J. Move over ANOVA: Progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:310–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.HLM [computer program]. Version 6. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drøyvold WB, Nilsen TIL, Krüger Ø, Holmen TL, Krokstad S, Midthjell K, Holmen J. Change in height, weight and body mass index: Longitudinal data from the HUNT Study in Norway. Int J Obes. 2006;30:935–939. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rissanen A, Heliovaara M, Aromaa A. Overweight and anthropometric changes in adulthood: A prospective study of 17 000 Finns. Int J Obes. 1988;12:391–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hek K, Demirkan A, Lahti J, Terracciano A, Teumer A, Cornelis MC, Amin N. A genome-wide association study of depressive symptoms. Biol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.033. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Milaneschi Y, An Y, Ferrucci L, Zonderman AB. Cohort effect on well-being: The legacy of economic hard times. Psychol Sci. doi: 10.1177/0956797612459658. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wassertheil-Smoller S, Applegate WB, Berge K, Chang CJ, Davis BR, Grimm R, Jr, Kostis J, Pressel S, Schron E. Change in depression as a precursor of cardiovascular events. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:553–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scott KM, Von Korff M, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Bromet EJ, Bruffaerts R, De Girolamo G, De Graaf R, Fernandez A, Gureje O, He Y, Kessler RC, Kovess V, Levinson D, Medina-Mora ME, Mneimneh Z, Oakley Browne MA, Posada-Villa J, Tachimori H, Williams D. Age patterns in the prevalence of DSM-IV depressive/anxiety disorders with and without physical co-morbidity. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1659–1669. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byers AL, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE, Friedman MB, Bruce ML. High occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:489–496. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meeks TW, Vahia IV, Lavretsky H, Kulkarni G, Jeste DV. A tune in “a minor” can “b major”: A review of epidemiology, illness course, and public health implications of subthreshold depression in older adults. J Affect Disords. 2011;129:126–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terracciano A, McCrae RR, Brant LJ, Costa PT., Jr Hierarchical linear modeling analyses of the NEO-PI-R scales in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Psychol Aging. 2005;20:493–506. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Small BJ, Hertzog C, Hultsch DF, Dixon RA. Stability and change in adult personality over 6 years: Findings from the Victoria Longitudinal Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58:P166–P176. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.p166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gerstorf D, Ram N, Estabrook R, Schupp J, Wagner GG, Lindenberger U. Life satisfaction shows terminal decline in old age: Longitudinal evidence from the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) Develop Psychol. 2008;44:1148–1159. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Age and depression. J Health Soc Behav. 1992;33(3):187–205. discussion 206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lynch SM, George LK. Interlocking trajectories of loss-related events and depressive symptoms among elders. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:S117–S125. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.2.s117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blazer D, Burchett B, Service C, George LK. The association of age and depression among the elderly: An epidemiologic exploration. J Gerontol. 1991;46(6):M210–M215. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.6.m210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hybels CF, Pieper CF, Blazer DG. The complex relationship between depressive symptoms and functional limitations in community-dwelling older adults: The impact of subthreshold depression. Psychol Med. 2009;39(10):1677–1688. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hybels CF, Blazer DG, Pieper CF. Toward a threshold for subthreshold depression: An analysis of correlates of depression by severity of symptoms using data from an elderly community sample. Gerontologist. 2001;41(3):357–365. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Albert SM, Bear-Lehman J, Burkhardt A. Mild depressive symptoms, self-reported disability, and slowing across multiple functional domains. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2012;24(2):253–260. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.