Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: Faecal Diversion for Management of Perianal Crohn’s Disease (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2019 Aug 18.

Published in final edited form as: Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Aug 11;42(7):783–792. doi: 10.1111/apt.13356

Abstract

Background:

Temporary faecal diversion (FD) is sometimes used for management of refractory perianal Crohn’s disease (CD) with variable success.

Aims:

We performed a systematic review with meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness, long-term outcomes, and factors associated with success of temporary FD for perianal CD.

Methods:

Through a systematic literature review through July 15, 2015, we identified 16 cohort studies (556 patients) reporting outcomes after temporary FD. We estimated pooled rates (with 95% confidence interval [CI]) of early clinical response, attempted and successful restoration of bowel continuity after temporary FD (without symptomatic relapse), and rates of re-diversion (in patients with attempted restoration) and proctectomy (with or without colectomy and end-ileostomy). We identified factors associated with successful restoration of bowel continuity.

Results:

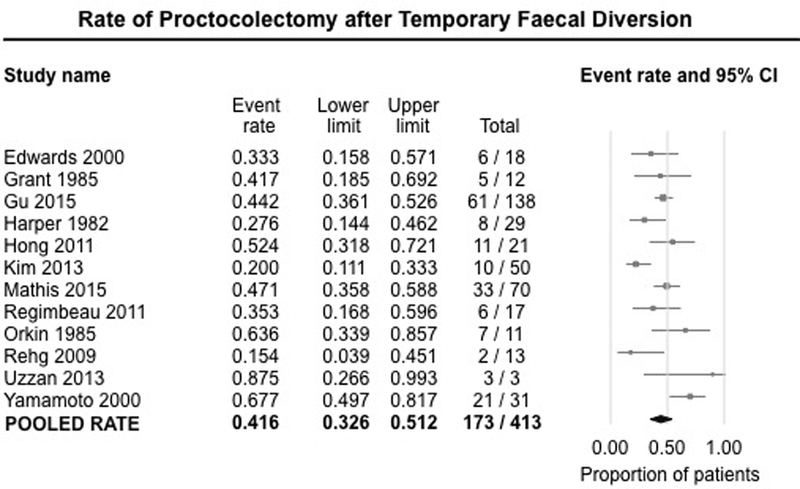

On meta-analysis, 63.8% (95%CI,54.1%−72.5%) of patients had early clinical response after FD for refractory perianal CD. Restoration of bowel continuity was attempted in 34.5% (95%CI,27.0%−42.8%) of patients, and was successful in only 16.6% (95%CI,11.8%−22.9%). Of those in whom restoration was attempted, 26.5% (95%CI,14.1%−44.2%) required re-diversion because of severe relapse. Overall, 41.6% (95%CI,32.6%−51.2%) of patients required proctectomy after failure of temporary FD. There was no difference in the successful restoration of bowel continuity after temporary FD in the pre-biologic or biologic era (13.7% vs. 17.6%,p=0.60), in part due to selection bias. Absence of rectal involvement was the most consistent factor associated with restoration of bowel continuity.

Conclusions:

Temporary FD may improve symptoms in approximately two-thirds of patients with refractory perianal CD, but bowel restoration is successful in only 17% of patients.

Keywords: Perianal Crohn’s disease, surgery, temporary ileostomy, stool diversion, recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Perianal fistulae are observed in 10–26% of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD),1, 2 and generally denote a more destructive phenotype, with higher rates of corticosteroid dependence, surgery and hospitalizations.3 Management of perianal CD requires a multi-disciplinary approach with a combination of immunosuppressive therapy, antibiotics and surgery for adequate control of sepsis and sometimes surgical resection.4 In the pre-biologic era, over two-thirds of patients with perianal CD required surgical intervention, with nearly one-third of patients requiring major abdominal surgery.2

Diversion of the faecal stream from severely inflamed segments of bowel has long been known to decrease CD-related inflammation.5, 6 A small subset of patients with refractory perianal CD are treated with temporary faecal diversion (FD) with the hope that the combination of diversion of faecal stream and optimal medical management may allow perianal CD to become less active and avoid the need for major surgery including proctectomy.7, 8 However, long-term outcomes of temporary FD, including rates of attempted and successful restoration of bowel continuity and need for additional surgery, including proctectomy, are poorly understood.9 Additionally, clinical and treatment-related factors associated with successful restoration of bowel continuity are unknown.10

If patients are to make informed decisions regarding temporary FD for refractory perianal CD, they must understand not only the likelihood of achieving fistula healing, but also the likelihood of restoring bowel continuity and further surgeries. Hence, we conducted a systematic review with meta-analysis to evaluate the clinical response and long-term outcomes of temporary FD for management of refractory perianal CD, primarily the successful restoration of bowel continuity. We also sought to identify factors associated with favorable outcome of temporary FD. We anticipate these data will help providers better communicate with patients the outcomes to be expected when using this treatment approach in clinical practice, thereby allowing for an improved shared decision-making process.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and the process followed a priori established protocol.11

Selection Criteria

Studies included in the systematic review met the following inclusion criteria: (a) cohort studies, case series and randomized controlled trials in (b) patients (adult or pediatric) with established severe perianal CD (with or without colonic CD), (c) who underwent temporary FD as means of treating perianal CD (with intent of restoring bowel continuity in the future), and (d) reported long-term outcomes following temporary FD, including rates of attempted and/or successful restoration of bowel continuity (without symptomatic relapse), re-diversion (in patients with attempted restoration) and additional perianal CD-related surgery (including total proctectomy, with or without colectomy and end-ileostomy).

We excluded the following studies: (a) case-control or cross-sectional studies; (b) studies with insufficient follow-up on the fate of FD (i.e., only report whether perianal disease improved with diversion, but do not report proportion in whom takedown was attempted, etc.); (c) studies in which FD was performed only for colonic CD without perianal disease; and (d) studies on CD recurrence after permanent ileostomy. In the case of multiple studies from the same cohort, we included data from the most recent comprehensive report.

Search Strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search of multiple electronic databases from inception to July 15, 2015 in adults with no language restrictions. The databases included: Ovid Medline In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Science, and Scopus. The search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced medical librarian with input from the study’s investigators, using controlled vocabulary supplemented with keywords, for studies on FD for perianal CD. The details of the search strategy are included in the Supplementary Appendix. The title and abstract of studies identified in the search were reviewed by two authors independently (SS, NSD) to exclude studies that did not address the research question of interest, based on pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria (see above). The full text of the remaining articles was examined to determine whether it contained relevant information. Next, the bibliographies of the selected articles and review articles on the topic were manually searched for additional studies. Third, a manual search of conference proceedings of major gastroenterology conferences (Digestive Disease Week, American College of Gastroenterology annual meeting, Advances in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases meeting organized by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, and European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization annual meeting) between 2010–2014 was conducted to identify additional studies published only in the abstract form.

Data Abstraction

Data on the following study-, patient- and treatment-related characteristics were abstracted onto a standardized form, by two authors independently (SS, JD): (a) study characteristics – primary author, time period of study/year of publication, geographic location, duration of follow-up after FD; (b) patient characteristics – age, sex, smoking, body mass index, CD location of disease, duration, prior surgeries; (c) treatment characteristics prior to FD – immunosuppressive (IM), anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF), combination IM-anti-TNF therapy, local/perianal surgical interventions; (d) outcome assessment – proportion of patients who noticed early clinical improvement (within 6 months) in perianal CD after diversion; proportion of patients in whom restoring bowel continuity was attempted after temporary FD (and after what period of time), and in what proportion was it successful (and duration of follow-up after restoration); proportion needing additional surgery after initial temporary FD (including proportion requiring re-diversion after attempted takedown); (e) covariates – co-management during time of FD – treatment with IM, anti-TNF or other biologics alone or in combination therapy; (f) factors associated with successful restoration of bowel continuity, as reported in individual studies, including baseline demographic and clinical variables as well as on-diversion treatment features (endoscopy findings prior to takedown, co-management of other medications, etc.). Any discrepancies were addressed by a joint re-evaluation of the original article.

The methodological quality of studies was assessed using National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) quality assessment for case series checklist.12

Outcomes Assessed

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients with successful (i.e., no relapse of perianal disease) restoration of bowel continuity after temporary FD for severe perianal CD. In addition, we estimated the proportion of patients with early clinical improvement in perianal disease following FD, the proportion of patients in whom restoration of bowel continuity was performed (regardless of eventual outcome) and the proportion of patients needing additional surgery (re-diversion in case bowel continuity was restored, proctectomy with or without colectomy and end-ileostomy, with or without local perianal procedures). In order to assess differences the in rates of primary outcome in the pre-biologic (before 1998) and biologic era (after 1998), we compared rates in studies enrolling patients in the corresponding period.

We, qualitatively and quantitatively (if feasible and reported in >2 studies), identified demographic, clinical and treatment-related factors associated with successful restoration of bowel continuity.

Statistical Analysis

We used the random-effects model described by DerSimonian and Laird to calculate pooled rates (and 95% confidence interval [CI]) of clinical improvement with FD, rates of attempted and successful restoration of bowel continuity, and rates of needing additional surgery post-FD.13 Due to lack of consistent reporting in multiple studies, we did not perform a quantitative meta-analysis of factors associated with successful restoration, but rather discussed them qualitatively. We assessed heterogeneity between study-specific estimates using the inconsistency index (I2), and used cut-offs of <30%, 30%−60%, 60%−75% and >75% to suggest low, moderate, substantial and considerable heterogeneity, respectively.14 Between-study sources of heterogeneity were investigated using subgroup analyses by stratifying original estimates according to time period of study (pre-biologic vs. biologic era vs. overlap). In this analysis, a p-value for differences between subgroups of <0.10 was considered statistically significant.14 Publication bias was assessed qualitatively using funnel plot asymmetry and quantitatively using the Egger’s regression test.15 All analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) version 2 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ).

RESULTS

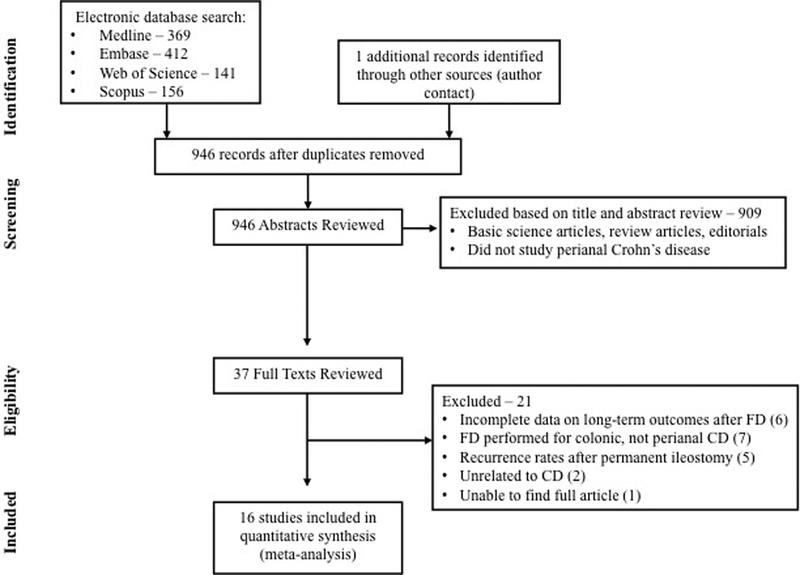

Of 1402 unique studies identified using our search strategy, 15 studies met our inclusion criteria.7–10, 16–26 We identified an additional unpublished study through personal communication with content experts,27 and hence, included a total of 16 studies in our meta-analysis. The primary reasons for exclusion after full-text review were: lack of data on long-term efficacy of FD, specifically rates of restoration of bowel continuity (6 studies),28–33 FD performed for colonic CD without severe perianal CD (7 studies),5, 6, 34–38 and reporting recurrence of CD after intended permanent ileostomy for colonic and/or perianal CD (5 studies).39–43 Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of study selection.

Figure 1.

Study selection flowchart

Characteristics and Quality of Included Studies

Supplementary Table 1 describes the characteristics of the patients included in the studies. Seven studies were performed exclusively in the pre-biologic era (i.e., all patients were operated and analyzed before the availability of anti-TNF agents),7, 16, 17, 20, 22, 23, 26 seven studies in the biologic era (i.e., all patients operated and analyzed after 1998, although it is not always clear what proportion were treated with anti-TNF agents before and/or after FD),9, 18, 19, 21, 24, 25, 27 and two studies in the overlapping period (i.e., some patients were operated before availability of anti-TNF agents in 1998 and others after 1998).8, 10 Six studies were performed in North America (including one pediatric study),9, 10, 16, 18, 22, 24 seven studies in Europe,7, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 26 and one each in Japan20 and Australia;8 one study was a multi-center cohort conducted in Europe and U.S.A.27 Perianal fistulae, anorectal sepsis and severe proctitis were the leading indications for temporary FD. Median follow-up after FD varied from 9 to 135 months in included studies. In most studies, diversion was performed with diverting ileostomy as opposed to colostomy.

Overall, the studies were at moderate risk of bias, with all studies being retrospective, and were performed in referral centers (consistent with the clinical practice of referring patients with complex perianal CD to these centers). Supplementary Table 2 details the quality of these included studies.

Outcomes after Faecal Diversion

Early Clinical Response:

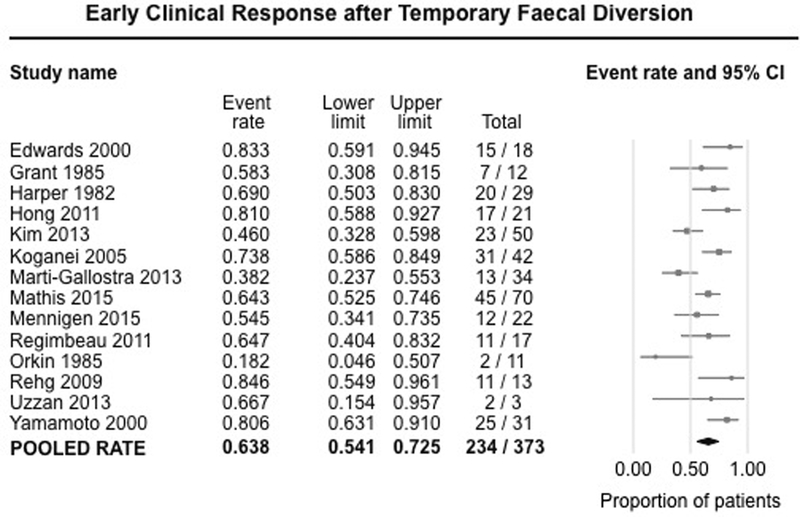

Fourteen studies (373 patients) reported early clinical response (usually defined clinically) within 3–6 months after FD for refractory perianal CD.7, 8, 16–27 On meta-analysis, 63.8% of patients (95% CI, 54.1%−72.1%) experienced improvement in symptoms after FD, with substantial heterogeneity (I2=64%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pooled summary rate (and 95% confidence interval) of early clinical response after temporary faecal diversion in patients with refractory perianal Crohn’s disease, using random effects model, based on 14 studies with 373 patients.

Attempted Restoration of Bowel Continuity:

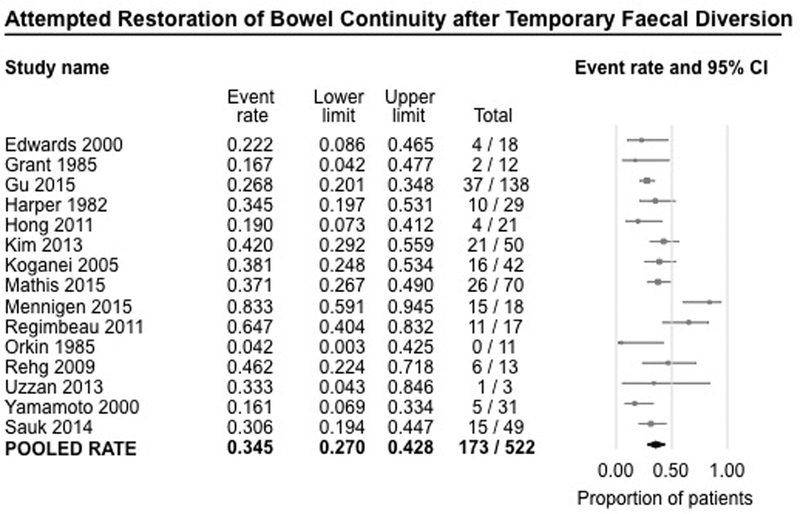

Fifteen studies (522 patients) reported rates of attempted restoration of bowel continuity after temporary FD.7–10, 16–27 On meta-analysis, restoration of bowel continuity was attempted only in 34.5% of patients (95% CI, 27.0%−42.8%), with substantial heterogeneity (I2=62%), even though FD was performed as a temporizing measure with the intention of restoring bowel continuity in the future (Figure 3). For the remaining patients, suboptimal clinical response and/or patient preference precluded attempting takedown of stoma. Most attempts at restoration of bowel continuity were made on average between 1–1.5 years after FD.

Figure 3.

Pooled summary rate (and 95% confidence interval) of attempted restoration of bowel continuity after temporary faecal diversion in patients with refractory perianal Crohn’s disease, using random effects model, based on 15 studies with 522 patients.

In exploring potential sources of heterogeneity, there was no difference in the rates of attempted restoration of bowel continuity in studies performed exclusively in the pre-biologic era (7 studies; rate, 31.3%; 95% CI, 19.6%−45.8%),7, 16, 17, 20, 22, 23, 26 in the biologic era (6 studies; rate, 43.6%; 95% CI, 31.4%−56.7%),9, 18, 21, 24, 25, 27 or in the overlapping period (patients from both pre-biologic and biologic era) (2 studies; rate, 25.9%; 95% CI, 19.7%−33.3%)8, 10 [p-value for difference between pre-biologic vs. biologic era, 0.15].

Successful Restoration of Bowel Continuity:

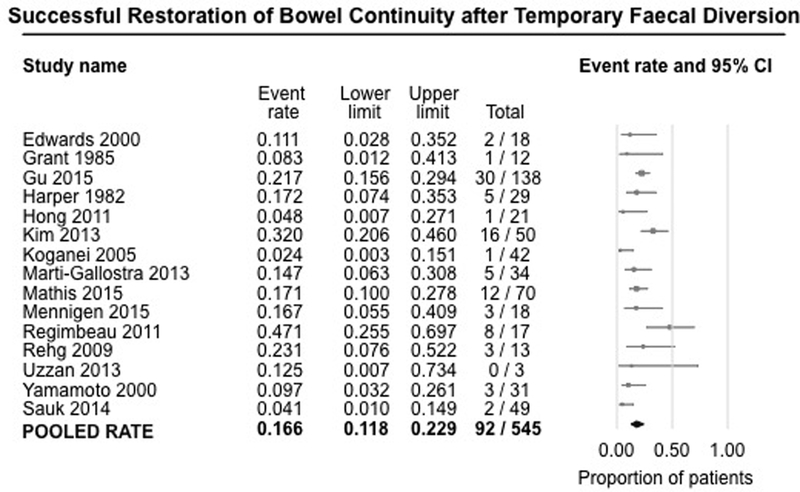

Fifteen studies (545 patients) reported rates of successful restoration of bowel continuity after temporary FD, i.e., without relapse of perianal CD.7–10, 16–21, 23–27 On meta-analysis, bowel continuity was successfully restored in only 16.6% of patients (95% CI, 11.8%−22.9%) undergoing temporary FD, with moderate heterogeneity (I2=54%) (Figure 4). Restoration of continuity was successful (without relapse of symptoms or need for additional surgery) in less than half of patients in whom it was attempted.

Figure 4.

Pooled summary rate (and 95% confidence interval) of successful restoration of bowel continuity after temporary faecal diversion in patients with refractory perianal Crohn’s disease, using random effects model, based on 15 studies with 545 patients.

There was no significant difference in the rates of successful restoration of bowel continuity in studies performed in the pre-biologic (6 studies; rate, 13.7%; 95% CI, 5.8%−29.4%)7, 16, 17, 20, 23, 26 or biologic era (7 studies; rate, 17.6%; 95% CI, 11.0%−26.8%),9, 18, 19, 21, 24, 25, 27 or in the overlapping period (patients from both pre-biologic and biologic era) (2 studies; rate, 13.7%; 95% CI, 3.2%−43.4%)8, 10 [p-value for difference between pre-biologic vs. biologic era, 0.60].

Need for Re-diversion after Restoration of Bowel Continuity:

Eleven studies (156 patients) reported the rates of re-diversion after failure of restoration of bowel continuity.7–10, 16–18, 20, 21, 24, 27 On meta-analysis of a subset of patients in whom restoration of bowel continuity was performed, 26.5% (95% CI, 14.1%−44.2%) required re-diversion (without proctectomy) for symptomatic management, with substantial heterogeneity between studies (I2=67%) (Supplementary Figure 1). Relapse of perianal CD after restoration of bowel continuity typically occurred within 2–6 months in included studies.

Need for Proctectomy after Temporary Diversion:

Twelve studies (413 patients) reported the overall rate of proctectomy after initial temporary FD for refractory perianal CD.7, 8, 10, 16–18, 22–27 On meta-analysis, 41.6% (95% CI, 32.6%−51.2%) of patients eventually required proctectomy due to failure of temporary FD (either primary non-response to initial diversion or following relapse of perianal disease on attempted restoration) (Figure 5). There was substantial heterogeneity between studies (I2=63%).

Figure 5.

Pooled summary rate (and 95% confidence interval) of eventual proctectomy after temporary faecal diversion in patients with refractory perianal Crohn’s disease, using random effects model, based on 12 studies with 413 patients

Factors Associated with Successful Restoration of Bowel Continuity

Nine studies analyzed factors associated with attempted restoration of bowel continuity, primarily as univariate analyses comparing the distribution of factors between those with restoration of bowel continuity vs. those with persistent FD.8–10, 17–19, 23, 26, 27 Absence or improvement in rectal disease was identified as the only consistent factor associated with restoration of bowel continuity, in four studies.10, 17, 19, 23 On multivariate analysis, Gu et al observed that rectal involvement was associated with a 7.5-fold higher risk of failure to achieve restoration of bowel continuity.10 Similarly, on univariate analysis, Regimbeau and colleagues23 observed that even after temporary FD, 88.9% of patients with rectal involvement eventually required total proctectomy as compared to only 12.5% of patients without rectal involvement. Marti-Gallostra et al observed that 44% of patients with decrease in endoscopic inflammation were able to successful undergo stoma takedown as compared to only 8% without objective evidence of decrease in inflammation.19 Studies did not identify a consistent association between distribution of CD (outside the rectum) and success in restoring bowel continuity after FD; in one study, quiescent small bowel disease (as opposed to active disease) was a protective factor associated with success, though this was not studied in other cohorts.23

Among therapy-related factors, use of biologic agents (either before or after FD) was not associated with an increased rate of successful restoration of bowel continuity in 5 studies that analyzed this factor, although it is unclear what proportion of patients were anti-TNF-experienced vs. anti-TNF-naïve at the time of FD.8–10, 18, 27 One study identified the use of immunosuppressive agents prior to FD as a risk factor associated with failure of restoration of bowel continuity.9 Mathis and coworkers identified prior CD-related surgery as a risk factor for failure to restore bowel continuity,27 and Gu et al observed non-use of loose setons (compared to the use of setons prior to FD for management of perianal CD) was predictive of restoration of bowel continuity, though it is unclear whether this was adjusted for baseline severity of perianal CD.10 None of the other medical therapies including 5-aminosalicylates or steroids were associated with outcomes.

No study identified any association between age (6 studies),9, 10, 18, 23, 26, 27 sex (5 studies),9, 10, 18, 23, 26 smoking (5 studies),9, 10, 18, 26, 27 indication for diversion (3 studies),9, 10, 23 type of diverting stoma (diverting ileostomy or colostomy; 2 studies),10, 23 duration of disease (2 studies),18, 26 diabetes mellitus (1 study)10 or Crohn’s Disease Activity Index score (1 study),26 and long-term outcomes after temporary FD.

Publication Bias and Time-trend Analysis

There was no evidence of publication bias (for the primary outcome of successful restoration of bowel continuity after temporary FD), both qualitatively on visualization of the funnel plot and quantitatively on Egger’s regression test (p=0.67).

In order to evaluate for temporal changes in rates of attempted or successful restoration, we performed a time-trend meta-analysis based on year of publication and observed no significant difference in the rates (Supplementary Figure 2A and B).

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 cohort studies of 556 patients who underwent temporary FD for refractory perianal CD, we made several key observations. First of all, FD results in early clinical improvement in approximately two-thirds of patients with refractory perianal CD. Second, despite early clinical improvement, restoration of bowel continuity can only be attempted in one-third of patients, suggesting that the majority of patients undergoing ‘temporary’ FD are unlikely to be considered good candidates for takedown of stoma (due to high risk of disease relapse or to patient preference). In fact, only 17% of patients undergoing temporary FD are likely to have successful restoration of bowel continuity, wherein there is sustained clinical response even after stoma takedown without need for further surgery. Of those who undergo stoma takedown with restoration of bowel continuity, about one-fourth would require re-diversion. Third, despite temporary FD, about 42% of patients will still eventually require proctectomy due to failure to achieve improvement with FD or relapse of symptoms on restoration of bowel continuity. Finally, rates of attempted or successful restoration of bowel continuity after FD have not changed significantly between the pre-biologic and biologic era, and the use of anti-TNF agents does not seem to be associated with successful stoma takedown. Only absence of rectal involvement appears to be associated with restoration of bowel continuity.

Perianal disease is a marker of severe CD. In a consecutive series of 356 patients with CD, of whom 86 had co-existing perianal CD, Galandiuk and colleagues observed that patients with perianal CD had on average 4 surgical procedures.28 Overall, 53 patients (62%) required FD at some point during their care, and at the end of follow-up, 42 patients (49%) required a permanent stoma. In a multicenter contemporary cohort, Mathis and coworkers observed that of 70 patients with perianal CD followed over a mean of 4.3 years after ‘temporary’ FD, 53 patients (75.7%) had a persistent stoma; 27 patients (38.6%) underwent proctectomy a median of 2.1 years after FD.27 These results were consistent with our observations, wherein only 15% of patients had successful takedown of stoma (without relapse of perianal disease) after temporary FD.

On systematically reviewing the existing literature, there were limited data on predictors of successful restoration of bowel continuity. When studied, the number of events in individual studies was small, limiting detailed statistical analysis. Absence of rectal involvement was the only consistent factor associated with high success rate. In the past, faecal challenge with instillation of faecal stoma effluent into the diverted segment has been observed as a predictor of the effect of restoring intestinal continuity in defunctioned Crohn’s colitis.44 Interestingly, we did not observe a significant association between the use of biologic agents and successful restoration of bowel continuity after temporary FD. On time-trend analysis, there was no significant increase in the rate of attempted or successful restoration of bowel continuity after FD in studies conducted in the biologic era compared to the pre-biologic era. Likewise, individual studies did not identify the use of anti-TNF agents before or after FD as predictive of stoma takedown. It is known that anti-TNF agents are not as efficacious in healing fistulae as inducing remission in luminal CD. The pooled efficacy of anti-TNF agents in healing of fistulizing perianal CD in randomized trials was estimated at 32.8% over 4–26 weeks of treatment.45 However, this apparent lack of effectiveness in improving outcomes of patients undergoing FD for perianal CD with the advent of anti-TNF agents may not necessarily represent lack of effectiveness, but probably represents selection bias. In the pre-biologic era, in the absence of effective therapy, FD may have been utilized early in management of perianal CD. With the availability of anti-TNF agents, patients with perianal CD are typically treated aggressively with anti-TNF agents, and a small subset of patients refractory to medical management would undergo FD. Hence, FD patients in the more recent biologic era were sicker and more refractory to therapy than in earlier decades. In studying temporal trends in rates of perianal surgical procedures, Sauk et al observed that only 10% of patients with perianal CD underwent diversion between 2009–11, compared to 18% between 2000–02 (p=0.006), suggesting that increasing use of biologics may have played a role in decreasing the need for diverting or surgical procedures for perianal CD.9

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this systematic review include: (a) comprehensive and systematic literature search with well-defined inclusion criteria; (b) assessment of multiple clinically relevant short- and long-term outcomes of temporary FD in the management of refractory perianal CD; (c) sub-group and time-trend sensitivity analyses to evaluate changes in long-term outcomes with the advent and use of biologic agents; and (d) systematic assessment of factors associated with long-term outcomes of temporary FD.

There are several limitations in our study. First, the meta-analysis was based on retrospective observational studies performed at tertiary referral centers with inherent selection bias. Given the rarity of this condition, randomized controlled trials would be difficult to perform. Second, while there was complete follow-up for most studies, long-term follow-up was not uniformly available. There were probably unmeasured confounding factors influencing decisions on management after creation of temporary FD, accounting for variations in practice and hence, moderate heterogeneity between studies. Third, there were subtle variations in definitions of early clinical response to FD. However, besides early clinical response, we included only hard and easily measureable end-points to minimize differences in definitions of outcomes. Finally, factors associated with attempted and successful restoration of bowel continuity were not consistently studied and reported. Most of these analyses were inadequate due to multiple statistical comparisons and hence, may represent chance findings, rather than true associations.

Implications for Clinical Practice

Temporary FD may be used for amelioration of severe perianal CD refractory to medical therapy, with good early clinical response. However, when such an approach is being considered, data on modest long-term outcomes with regard to attempted and successful restoration of bowel continuity and avoiding proctectomy should be discussed with the patients, to allow an informed shared decision-making process. It may be useful for patients who are reluctant to the idea of a permanent stoma at initial consultation, wherein temporary FD may improve acceptability of the stoma. While factors associated with successful restoration of bowel continuity after temporary FD are poorly understood, healing of rectal disease should be a minimum prerequisite before stoma takedown.

In conclusion, temporary FD often results in early clinical response in patients with refractory perianal CD, but successful restoration of bowel continuity is uncommon and possible in only 15% of patients, despite the use of biologic agents. With the advent of newer biologic agents and strategies to optimize performance of existing agents (such as combination immunosuppressive therapy, early combination therapy with “top-down” approach, therapeutic drug monitoring), we may be able to decrease the proportion of patients requiring FD to treat refractory perianal CD. Future studies focusing on a refractory group of patients who do require FD for management are warranted, especially to study factors predictive of successful restoration of bowel continuity.

Supplementary Material

10

11

7

8

Supplementary Figure 1.Pooled summary rate (and 95% confidence interval) of re-diversion in patients who underwent restoration of bowel continuity after temporary faecal diversion in patients with refractory perianal Crohn's disease.

9

Supplementary Figure 2.Time-trend analysis - pooled summary rate (and 95% confidence interval) of (A) attempted and (B) successful restoration of bowel continuity after temporary faecal diversion in patients with refractory perianal Crohn's disease, by year of publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the authors have any relevant disclosures.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Ingle SB, Loftus EV Jr., The natural history of perianal Crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis 2007;39(10):963–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz DA, Loftus EV Jr., Tremaine WJ, et al. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology 2002;122(4):875–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2006;130(3):650–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz DA, Ghazi LJ, Regueiro M, et al. Guidelines for the multidisciplinary management of Crohn’s perianal fistulas: summary statement. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21(4):723–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIlrath DC. Diverting ileostomy or colostomy in the management of Crohn’s disease of the colon. Arch Surg 1971;103(2):308–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burman JH, Thompson H, Cooke WT, Williams JA. The effects of diversion of intestinal contents on the progress of Crohn’s disease of the large bowel. Gut 1971;12(1):11–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards CM, George BD, Jewell DP, Warren BF, Mortensen NJ, Kettlewell MG. Role of a defunctioning stoma in the management of large bowel Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg 2000;87(8):1063–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong MK, Craig Lynch A, Bell S, et al. Faecal diversion in the management of perianal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis 2011;13(2):171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauk J, Nguyen D, Yajnik V, et al. Natural history of perianal Crohn’s disease after fecal diversion. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20(12):2260–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu J, Valente MA, Remzi FH, Stocchi L. Factors affecting the fate of faecal diversion in patients with perianal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis 2015;17(1):66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151(4):264–9, W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) website. Quality assessment for case series. 11 Available online at http://www.nice.org.uk:80/aboutnice/howwework/developingniceclinicalguidelines/clinicalguidelinedevelopmentmethods/theguidelinesmanual2007/the_guidelines_manual__chapter_7_reviewing_and_grading_the_evidence.jsp. Accessed on June 28, 2015

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7(3):177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315(7109):629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant DR, Cohen Z, McLeod RS. Loop ileostomy for anorectal Crohn’s disease. Can J Surg 1986;29(1):32–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harper PH, Kettlewell MG, Lee EC. The effect of split ileostomy on perianal Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg 1982;69(10):608–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Ito N, Da Silva G, Wexner S. Temporary fecal diversion for perianal crohn’s disease may actually be permanent in the majority of patients. Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56 (4):e187. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marti-Gallostra M, Myrelid P, Lovegrove R, Travis S, George B. Has the role of a defunctioning stoma for large bowel Crohn’s disease changed in the biological era? J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:P497. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koganei K, Kimura H, Arai K, Sugita A, Fukushima T. Efficacy and problems of fecal diversion for intractable anorectal complications of Crohn’s disease. [Japanese]. Jpn J Gastrointest Surg 2005;38(10):1543–1548. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mennigen R, Heptner B, Senninger N, Rijcken E. Temporary fecal diversion in the management of colorectal and perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2015;2015:286315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orkin BA, Telander RL. The effect of intra-abdominal resection or fecal diversion on perianal disease in pediatric Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Surg 1985;20(4):343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regimbeau JM, Panis Y, Cazaban L, et al. Long-term results of faecal diversion for refractory perianal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis 2001;3(4):232–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehg KL, Sanchez JE, Krieger BR, Marcet JE. Fecal Diversion in Perirectal Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease is an Underutilized and Potentially Temporary Means of Successful Treatment. Am Surg 2009;75(8):715–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uzzan M, Stefanescu C, Maggiori L, Panis Y, Bouhnik Y, Treton X. Case series: does a combination of anti-tnf antibodies and transient ileal fecal stream diversion in severe Crohn’s colitis with perianal fistula prevent definitive stoma? Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108(10):1666–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto T, Allan RN, Keighley MR. Effect of fecal diversion alone on perianal Crohn’s disease. World J Surg 2000;24(10):1258–62; discussion 1262–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathis K, Pemberton JH, Tiret E, Bemelman W, Michelassi F, Soderholm J, Oresland T, Remzi F, D’Hoore A. Clinical Effectiveness and Outcome of Diversion in Refractory Crohn Colitis with and without Perianal Fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 2015;58(5):S49 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galandiuk S, Kimberling J, Al-Mishlab TG, Stromberg AJ. Perianal Crohn disease: predictors of need for permanent diversion. Ann Surg 2005;241(5):796–801; discussion 801–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linares L, Moreira LF, Andrews H, Allan RN, Alexander-Williams J, Keighley MR. Natural history and treatment of anorectal strictures complicating Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg 1988;75(7):653–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasparek MS, Glatzle J, Temeltcheva T, Mueller MH, Koenigsrainer A, Kreis ME. Long-term quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease and perianal fistulas: influence of fecal diversion. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50(12):2067–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makowiec F, Schmidtke C, Paczulla D, Lamberts R, Becker HD, Starlinger M. Progression and prognosis of Crohn’s colitis. Z Gastroenterol 1997;35(1):7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seemann NM, Elkadri A, Walters TD, Langer JC. The role of surgery for children with perianal Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Surg 2015;50(1):140–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spivak J, Landers CJ, Vasiliauskas EA, et al. Antibodies to I2 predict clinical response to fecal diversion in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12(12):1122–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coscia M, Gentilini L, Laureti S, et al. Risk of permanent stoma in extensive Crohn’s colitis: the impact of biological drugs. Colorectal Dis 2013;15(9):1115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chernoguz A, Falcone R, Nathan JD, et al. Role of fecal diversion in pediatric colorectal crohn’s disease in the era of anti-TNF-alpha therapy. Gastroenterology 2012;142(5):S1053–S1054. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fichera A, McCormack R, Rubin VA, Hurst RD, Michelassi F. Long-term outcome of surgically treated Crohn’s colitis: A prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48(5):963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korelitz BI, Cheskin LJ, Sohn N, Sommers SC. The fate of the rectal segment after diversion of the fecal stream in Crohn’s disease: Its implications for surgical management. J Clin Gastroenterol 1985;7(1):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guillem JG, Roberts PL, Murray JJ, Coller JA, Veidenheimer MC, Schoetz DJ Jr., Factors predictive of persistent or recurrent Crohn’s disease in excluded rectal segments. Dis Colon Rectum 1992;35(8):768–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amiot A, Gornet JM, Baudry C, et al. Crohn’s disease recurrence after total proctocolectomy with definitive ileostomy. Dig Liver Dis 2011;43(9):698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lapidus A, Bernell O, Hellers G, Lofberg R. Clinical course of colorectal Crohn’s disease: a 35-year follow-up study of 507 patients. Gastroenterology 1998;114(6):1151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leal-Valdivieso C, Marin I, Manosa M, et al. Should we monitor Crohn’s disease patients for postoperative recurrence after permanent ileostomy? Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18(1):E196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lopez J, Konijeti GG, Nguyen DD, Sauk J, Yajnik V, Ananthakrishnan AN. Natural history of Crohn’s disease following total colectomy and end ileostomy. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20(7):1236–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Recurrence after colectomy in Crohn’s colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44(5):647–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harper PH, Lee EC, Kettlewell MG, Bennett MK, Jewell DP. Role of the faecal stream in the maintenance of Crohn’s colitis. Gut 1985;26(3):279–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106(4):644–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

10

11

7

8

Supplementary Figure 1.Pooled summary rate (and 95% confidence interval) of re-diversion in patients who underwent restoration of bowel continuity after temporary faecal diversion in patients with refractory perianal Crohn's disease.

9

Supplementary Figure 2.Time-trend analysis - pooled summary rate (and 95% confidence interval) of (A) attempted and (B) successful restoration of bowel continuity after temporary faecal diversion in patients with refractory perianal Crohn's disease, by year of publication.