Risk factors for coronary artery disease in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: United Kingdom prospective diabetes study (UKPDS: 23) (original) (raw)

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate baseline risk factors for coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Design: A stepwise selection procedure, adjusting for age and sex, was used in 2693 subjects with complete data to determine which risk factors for coronary artery disease should be included in a Cox proportional hazards model.

Subjects: 3055 white patients (mean age 52) with recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus and without evidence of disease related to atheroma. Median duration of follow up was 7.9 years. 335 patients developed coronary artery disease within 10 years.

Outcome measures: Angina with confirmatory abnormal electrocardiogram; non-fatal and fatal myocardial infarction.

Results: Coronary artery disease was significantly associated with increased concentrations of low density lipoprotein cholesterol, decreased concentrations of high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and increased triglyceride concentration, haemoglobin A1c, systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose concentration, and a history of smoking. The estimated hazard ratios for the upper third relative to the lower third were 2.26 (95% confidence interval 1.70 to 3.00) for low density lipoprotein cholesterol, 0.55 (0.41 to 0.73) for high density lipoprotein cholesterol, 1.52 (1.15 to 2.01) for haemoglobin A1c, and 1.82 (1.34 to 2.47) for systolic blood pressure. The estimated hazard ratio for smokers was 1.41(1.06 to 1.88).

Conclusion: A quintet of potentially modifiable risk factors for coronary artery disease exists in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. These risk factors are increased concentrations of low density lipoprotein cholesterol, decreased concentrations of high density lipoprotein cholesterol, raised blood pressure, hyperglycaemia, and smoking.

Key messages

- Coronary artery disease is the major cause of mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Patients without evidence of disease related to atheroma at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus had an increased standardised mortality ratio compared with the population of the United Kingdom

- 11% of patients in this study had a myocardial infarction or developed angina over a median of 8 years’ follow up

- The potentially modifiable risk factors for coronary artery disease were increased concentrations of low density lipoprotein cholesterol, decreased concentrations of high density lipoprotein cholesterol, hypertension, hyperglycaemia, and smoking; these are also risk factors for coronary artery disease in the general population

- Evidence is needed on whether modifying these risk factors will reduce coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus have a twofold to threefold increased incidence of diseases related to atheroma,1 and those who present in their 40s and 50s have a twofold increased total mortality.2 In the United Kingdom the incidence of macrovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus is twice that of microvascular disease.3 The greater mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus than in the general population cannot be explained only by the presence of the three classic risk factors for coronary artery disease—that is, smoking, hypertension, and an increased plasma cholesterol concentration.4

Previous prospective studies of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus had comparatively few patients and cardiovascular end points.5–11 Many of these studies have not measured the concentration of low density lipoprotein cholesterol, potentially the most important lipid fraction.12,13

We report a prospective study of white patients with recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. After entry to the United Kingdom prospective diabetes study14 patients were assessed for baseline risk factors after initial treatment by diet for 3 months. The association of coronary artery disease with baseline risk factors has been assessed irrespective of subsequent treatments.

Subjects and methods

Patients

Between 1977 and 1991, 5102 patients aged 25 to 65 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus based on a fasting plasma glucose concentration >6 mmol/l on two occasions were recruited to the study14; 4775 (94%) had fasting plasma glucose values >7.0 mmol/l, which is consistent with the American Diabetic Association’s definition of diabetes. Of the 7108 patients originally referred for entry to the study, 2006 (28%) were excluded. These were of a similar age and sex and had a similar fasting plasma glucose concentration as those patients included in the study. The main reasons for exclusion were myocardial infarction in the previous year, current angina or heart failure, accelerated hypertension, proliferative or preproliferative retinopathy, renal failure with a plasma creatinine concentration >175 μmol/l, other life threatening disease such as cancer, an illness requiring systemic steroids, an occupation which precluded insulin treatment, language difficulties, or ketonuria >3 mmol/l suggestive of insulin dependent diabetes mellitus.

The study was approved by the ethics committee in each of the 23 centres: Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford; Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen; General Hospital, Birmingham; St George’s Hospital and Hammersmith Hospital, London; City Hospital, Belfast; North Staffordshire Royal Infirmary, Stoke on Trent; Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast; St Helier Hospital, Carshalton; Whittington Hospital, London; Norfolk and Norwich Hospital; Lister Hospital, Stevenage; Ipswich Hospital; Ninewells Hospital, Dundee; Northampton Hospital; Torbay Hospital; Peterborough General Hospital; Scarborough Hospital; Derbyshire Royal Infirmary; Manchester Royal Infirmary; Hope Hospital, Salford; Leicester General Hospital; Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital. All patients gave their informed consent to take part in the study.

The initial treatment by diet for 3 months was completed by 4178 white patients,14 with a mean loss of 5 kg body weight, but only 867 (16.9%) were able to achieve a near normal fasting plasma glucose concentration of <6 mmol/l. Cardiovascular disease was evident in 381 (7.5%) patients, of whom 58 (15.2%) had previous myocardial infarction, 144 (37.8%) a definite electrocardiographic Q wave abnormality on Minnesota coding, 7 (1.8%) angina, 1 (0.3%) heart failure, 120 (31.5%) intermittent claudication, and 51 (13.4%) a previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Only 2693 (70.9%) of the 3797 datasets could be analysed for all variables, as biochemical measurements were not undertaken until 1981, and some patients had no valid data for one or more of the other variables. Sufficient data were available from 3055 (80.5%) patients for the final Cox model analysis, and 2161 (56.9%) patients had ophthalmic photographic data available for the assessment of the effect of retinopathy.

After the initial treatment diet, patients were randomly allocated to different treatments according to the protocol of the United Kingdom prospective diabetes study.14 This paper does not include any reference to treatment allocations, actual treatment, or diabetes control during the 10 years of follow up.

Follow up, identification, and classification of end points

Patients were seen every three months in the clinics, and any events that were clinically important were noted. To ascertain whether predetermined criteria for the end points were attained two independent doctors received full information on the patients but without details of treatment.14 Any discrepancies between the two doctors were adjudicated by two independent senior doctors. All end points were coded according to ICD-9 (international classification of disease, 9th revision).15

Three aggregate end points were evaluated: coronary artery disease—that is, fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction or clinical angina—with an abnormal electrocardiogram at rest or after a treadmill test; fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction; and fatal myocardial infarction.

Baseline risk factors assessment

Height, waist, and hip circumferences were measured, and the smoking status and amount of exercise taken were ascertained by questionnaire.14 Retinopathy was assessed by modified Wisconsin grading of four colour photographs of each eye taken at 30° to the horizontal.14 Blood pressure was recorded as the mean of measurements taken 2 and 9 months after diagnosis with electronic sphygmomanometers. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ⩾160 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ⩾90 mm Hg, or both, or antihypertensive treatment. After the initial treatment diet, patients were fasted overnight and the following concentrations measured: fasting plasma glucose, haemoglobin A1c, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and insulin.14,16

Statistical analyses

Data are reported as means (SD), geometric means (1 SD interval), or percentages. Variables for patients included in or excluded from the analyses were compared by t tests, χ2 tests, or Fisher’s exact tests.

Standardised mortality ratio in the patients was calculated from the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys death rates for the general population of England and Wales for the same calendar period, with stratification by sex and age in periods of five years.17,18

Age was categorised as <50, 50-54, 55-59, or ⩾60 years. Continuous variables were grouped into thirds. The effect of potential risk factors on the three aggregate end points was assessed by Cox proportional hazards models,19 with censoring at 10 years’ follow up. The relation of single risk factors with events after adjustment for age and sex was assessed in 2693 patients with all risk factors measured. Multivariate selection of risk factors was done by a stepwise procedure after adjustment for age and sex. Estimated hazard ratios are represented graphically, with 95% confidence intervals estimated for each group by treating the relative risks as floating absolute risks so that the appropriate variability for each group is shown.20

Baseline biochemical and blood pressure values were corrected for any effects from regression to the mean by examining repeat values at six months in 497 patients who had remained on the diet treatment alone. The effect of a unit increment of risk factors on coronary artery disease (1 mmol/l in low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration, 0.1 mmol/l in high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration, 10 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure, and 1% in haemoglobin A1c) was estimated by fitting each factor as a continuous variable in a stepwise selected Cox model, leaving other risk factors as categorical variables and adjusting for regression to the mean. Statistical analyses were performed using sas version 6.1.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline risk factors assessed for the 2693 white patients who had no previous indication of disease related to atheroma and had complete data when studied after the initial treatment diet. The men who were entered into the United Kingdom prospective diabetes study but excluded from this analysis because of previous cardiovascular disease were older (mean age 56 (SD7) years), had higher systolic blood pressure (mean 141(20) mm Hg), were more likely to be hypertensive (46%), and were more likely to be smokers (10% had never smoked, 51% were ex-smokers, and 39% were current smokers) (P<0.01 for each). Women who were excluded from the study were also older (mean age 56 (8) years) and had higher systolic blood pressure (mean 145 (20) mm Hg) (P<0.01 for each). Baseline concentrations of total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglyceride did not differ in subjects according to the presence of disease related to atheroma (P>0.01).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in 2693 white patients with no indication of disease related to atheroma. Results are means (SD) or geometric mean (1 SD interval) unless stated otherwise

| Variable | Men (n=1564) | Women (n=1129) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 52 (9) | 53 (9) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.1 (4.7) | 29.4 (6.4) |

| Waist:hip ratio | 0.95 (0.06) | 0.87 (0.08) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 133 (18) | 139 (20) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 82 (10) | 83 (10) |

| No (%) of patients with hypertension | 508 (32) | 506 (45) |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/l) | 8.3 (2.8) | 9.2 (3.0) |

| Haemoglobin A1c (%) | 6.9 (1.7) | 7.4 (1.8) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.2 (1.0) | 5.7 (1.2) |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/l) | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.8 (1.1) |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.04 (0.23) | 1.10 (0.24) |

| Triglyceride (mmol/l) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.4) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.6) |

| Fasting plasma insulin (mU/l) | 11.3 (6.6, 19.4) | 13.2 (7.7, 22.7) |

| Exercise (No (%) of subjects) | ||

| Sedentary | 261 (17) | 251 (22) |

| Moderate | 496 (32) | 440 (39) |

| Active | 692 (44) | 428 (38) |

| Fit | 115 (7) | 10 (1) |

| Smoking (No (%) of subjects) | ||

| Never | 344 (22) | 501 (44) |

| Ex-smoker | 712 (46) | 297 (27) |

| Current | 508 (32) | 331 (29) |

Standardised mortality ratio

During the first five years of the study the standardised mortality ratio was not very different from that in the general population, possibly because patients with life threatening illnesses were excluded from the study (table 2). After the first five years of the study patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus had an increased total mortality compared with the general population.

Table 2.

Standardised mortality ratios for 5071 patients recently diagnosed with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus compared with general population

| Years since randomisation | No of patients | No observed | No expected | Standardised mortality ratio | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||

| 0 to <5 | 2992 | 153 | 162 | 0.94 | 0.78 |

| 5 to <10 | 2267 | 161 | 118 | 1.36 | <0.001 |

| ⩾10 | 566 | 42 | 26 | 1.62 | 0.002 |

| Women | |||||

| 0 to <5 | 2079 | 69 | 72 | 0.96 | 0.64 |

| 5 to <10 | 1581 | 84 | 55 | 1.52 | <0.001 |

| ⩾10 | 409 | 28 | 12 | 2.42 | <0.0001 |

Relation of baseline risk factors with adjustment for age and sex

Table 3 shows the relation of potential risk factors, stratified by thirds, to coronary artery disease in 280 patients with end points. Important variables were low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration, high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration, and also triglyceride concentration, haemoglobin A1c, systolic blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose concentration, and smoking; each of these had a positive association except high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration. Similar associations were seen for fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction (192 patients with end points) and fatal myocardial infarction (79 patients with end points). Retinopathy was associated with fatal myocardial infarction (P=0.005) but not with fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction (P=0.124) or with coronary artery diseases (P=0.082).

Table 3.

Relation of potential risk factors to cardiac end points after adjustment for age and sex, in 2693 white patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus

| Variable | Distribution | Coronary artery disease (n=280) | Non-fatal or fatal myocardial infarction (n=192) | Fatal myocardial infarction (n=79) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower third | Upper third | P value | Estimated hazard ratios for each third* | P value | Estimated hazard ratios for each third* | P value | Estimated hazard ratios for each third | |||||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.8 | 29.0 | 0.65 | 0.083 | 0.46 | |||||||||

| Waist:hip ratio | 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.50 | 0.89 | |||||||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 125 | 142 | 0.0032 | 1 | 1.52 | 1.72 | 0.027 | 1 | 1.44 | 1.70 | 0.011 | 1 | 1.14 | 2.17 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 79 | 87 | 0.025 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.45 | 0.0061 | 1 | 1.17 | 1.72 | <0.0001 | 1 | 0.79 | 2.09 |

| Hypertension | 0.018 | 1 | 1.34 | 0.022 | 1 | 1.40 | 0.008 | 1 | 1.83 | |||||

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/l) | 7.3 | 9.7 | 0.016 | 1 | 1.31 | 1.54 | 0.13 | 0.017 | 1 | 1.83 | 2.24 | |||

| Haemoglobin A1c (%) | 6.2 | 7.5 | 0.0003 | 1 | 1.64 | 1.78 | 0.01 | 1 | 1.47 | 1.71 | 0.0099 | 1 | 1.09 | 2.11 |

| Cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.88 | 5.77 | <0.0001 | 1 | 1.79 | 1.93 | 0.0086 | 1 | 1.62 | 1.67 | 0.027 | 1 | 1.98 | 2.01 |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/l) | 3.02 | 3.89 | <0.0001 | 1 | 1.48 | 2.29 | 0.0002 | 1 | 1.44 | 2.11 | 0.0043 | 1 | 1.06 | 2.25 |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/l) | 0.95 | 1.15 | <0.0001 | 1 | 0.87 | 0.51 | 0.0085 | 1 | 0.84 | 0.57 | 0.42 | |||

| Triglyceride (mmol/l) | 1.22 | 1.87 | <0.0001 | 1 | 1.63 | 1.93 | 0.011 | 1 | 1.40 | 1.72 | 0.079 | |||

| Insulin (mU/l) | 9.7 | 15.6 | 0.16 | 0.022 | 1 | 1.18 | 1.63 | 0.86 | ||||||

| Exercise (sedentary, moderate, active, fit) | 0.54 | 0.044 | 1 | 0.73 0.58 0.74† | 0.57 | |||||||||

| Smoking (never smoked, ex-smoker, current smoker) | 0.016 | 1 | 1.18 | 1.55 | 0.015 | 1 | 1.27 | 1.74‡ | 0.57 |

Stepwise selection of risk factors

Table 4 shows the selected risk factors with P values from the stepwise multivariate Cox models. Factors that were not important were body mass index, waist to hip ratio, exercise, triglyceride concentration, and fasting plasma glucose or insulin concentration, and these were not included in the final model. The exclusion of triglyceride concentration and not high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration was not due solely to imprecision of measurements, since baseline triglyceride concentration correlated with the values 6 months later in subjects randomised to, and remaining on, the diet (_rs_=0.72 (95% confidence interval 0.68 to 0.76)). This correlation was greater than the correlation between repeated high density lipoprotein measurements (_rs_=0.52 (0.45 to 0.58)). Baseline triglyceride concentration correlated with high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration _(rs_=−0.27 (P<0.0001)). No significant interaction term was identified between high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration and low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration.

Table 4.

Stepwise selection of risk factors, adjusted for age and sex, in 2693 white patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus with dependent variable as time to first event. P values are significance of risk factor after accounting for all other risk factors in model

| Position in model | Coronary artery disease (n=280) | Non-fatal or fatal myocardial infarction (n=192) | Fatal myocardial infarction (n=79) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | P value | Variable | P value | Variable | P value | |

| First | Low density lipoprotein cholesterol | <0.0001 | Low density lipoprotein cholesterol | 0.0022 | Diastolic blood pressure | 0.0012 |

| Second | High density lipoprotein cholesterol | 0.0001 | Diastolic blood pressure | 0.0074 | Low density lipoprotein cholesterol | 0.012 |

| Third | Haemoglobin A1c | 0.0022 | Smoking | 0.025 | Haemoglobin A1c | 0.024 |

| Fourth | Systolic blood pressure | 0.0065 | High density lipoprotein cholesterol | 0.026 | ||

| Fifth | Smoking | 0.056 | Haemoglobin A1c | 0.053 |

Estimated hazard ratios

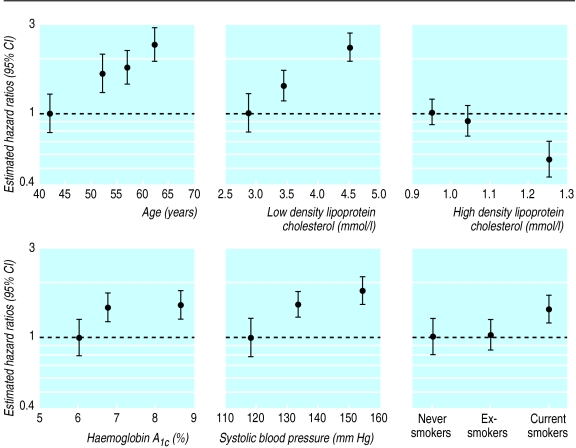

Table 5 and the figure show the Cox model estimated hazard ratios for age and sex and the stepwise selected variables for coronary artery disease in 3055 patients (335 with a coronary artery disease). A similar pattern of hazard ratios was seen for fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction (233 patients with an event) and fatal myocardial infarction (103 patients with an event). Although diastolic blood pressure had a stronger relation than systolic blood pressure with any myocardial infarction or fatal myocardial infarction, replacement by systolic blood pressure did not affect the results.

Table 5.

Estimated hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for coronary artery disease in 3055 patients, fitting same explanatory variables for all three dependent variables

| Dependent variable | Coronary artery disease | Fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction | Fatal myocardial infarction |

|---|---|---|---|

| No of patients with event | 335 | 233 | 103 |

| Age (years) | |||

| <50 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 50-54 | 1.65 (1.18 to 2.31) | 1.76 (1.15 to 2.70) | 5.56 (2.07 to 14.95) |

| 55-59 | 1.78 (1.29 to 2.46) | 2.41 (1.62 to 3.57) | 8.70 (3.37 to 22.48) |

| ⩾60 | 2.35 (1.71 to 3.23) | 2.80 (1.88 to 4.17) | 13.86 (5.43 to 35.41) |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Men | 2.12 (1.65 to 2.73) | 2.62 (1.91 to 3.58) | 4.13 (2.53 to 6.76) |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/l) | |||

| <3.02 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ⩾3.02 to <3.89 | 1.41 (1.05 to 1.90) | 1.41 (1.00 to 2.00) | 1.15 (0.67 to 1.97) |

| ⩾3.89 | 2.26 (1.70 to 3.00) | 2.11 (1.50 to 2.95) | 2.32 (1.41 to 3.81) |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/l) | |||

| <0.95 | 1 | 1 | 1** |

| ⩾0.95 to <1.15 | 0.90 (0.71 to 1.15) | 0.94 (0.70 to 1.26) | 1.16 (0.73 to 1.84) |

| ⩾1.15 | 0.55 (0.41 to 0.73) | 0.65 (0.47 to 0.91) | 0.84 (0.51 to 1.39) |

| Haemoglobin A1c (%) | |||

| <6.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ⩾6.2 to <7.5 | 1.47 (1.12 to 1.95) | 1.26 (0.91 to 1.75) | 0.98 (0.58 to 1.65) |

| ⩾7.5 | 1.52 (1.15 to 2.01) | 1.42 (1.03 to 1.98) | 1.72 (1.06 to 2.77) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||

| <125 | 1 | 1* | 1* |

| ⩾125 to <142 | 1.52 (1.12 to 2.06) | 1.45 (1.01 to 2.08) | 1.22 (0.66 to 2.24) |

| ⩾142 | 1.82 (1.34 to 2.47) | 1.76 (1.22 to 2.54) | 2.36 (1.33 to 4.18) |

| Smoking | |||

| Never smoked | 1 | 1 | 1** |

| Ex-smoker | 1.03 (0.77 to 1.37) | 1.08 (0.75 to 1.54) | 0.65 (0.39 to 1.09) |

| Current smoker | 1.41 (1.06 to 1.88) | 1.58 (1.11 to 2.25) | 1.03 (0.62 to 1.70) |

Fitting the risk factors for coronary artery disease as continuous variables, with allowance for regression to mean, indicated that for each increment of 1 mmol/l in low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration there was a 1.57-fold (95% confidence interval 1.37 to 1.79) increased risk of coronary artery disease. For each positive increment of 0.1 mmol/l in high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration there was a 0.15-fold (0.08 to 0.22) decrease in risk, for each increment of 10 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure a 1.15-fold (1.08 to 1.23) increase, and for each increment of 1% in haemoglobin A1c a 1.11-fold (1.02 to 1.20) increase in risk.

The retinopathy grading was not significantly related to any of the three aggregate end points when added to the multivariate models, including age, sex, and the other risk factors in table 4.

Discussion

This study shows that in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus increased concentrations of low density lipoprotein cholesterol, decreased concentrations of high density lipoprotein cholesterol, hyperglycaemia, hypertension, and smoking (all measured on completion of a treatment diet after diagnosis), are risk factors for coronary artery disease, defined as fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction or angina. Previous studies have shown inconsistent results, being dependent on univariate analyses in small studies, with few patients having clinical end points. Total cholesterol concentration was reported to be a risk factor in some5,7,21 but not other studies,6,8,22 and most had not measured both low density lipoprotein cholesterol and high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations. Hyperglycaemia was similarly reported as a risk factor in some5,6,8,11,21,22 but not other studies,7 and hypertension similarly in some5,22 but not other studies.6–8,11,21 The present study shows that patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus have the same risk factors for coronary artery disease as the general population.23 This study confirms that patients with non-insulin diabetes mellitus have an increased total mortality compared with the general population, although this was not apparent in the initial 5 years, probably because diabetic patients with life threatening illness were excluded from the United Kingdom prospective diabetes study.

Major risk factors

Low density lipoprotein and total cholesterol

—An increased concentration of low density lipoprotein cholesterol or total cholesterol at baseline was a major risk factor for coronary artery disease. This is similar to the general population.13,24,25 Increased concentrations of low density lipoprotein cholesterol may be more pathogenic in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus than in non-diabetic patients because of the presence of small dense low density lipoprotein cholesterol particles26 and oxidation of glycated low density lipoprotein cholesterol.27 The 1.57 increased risk for an increment of 1 mmol/l in low density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration equates to a 36% risk reduction for a decrement of 1 mmol/l , similar to the 31% risk reduction achieved with a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitor in men with hypercholesterolaemia.13 The subgroup analysis of the simvastatin study28 showed that the diabetic patients had similar protection to that of non-diabetic patients.25 A decreased concentration of high density lipoprotein cholesterol was an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease. The 15% decrease in the risk of coronary artery disease associated with a 0.1 mmol/l increment in high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration is compatible with the 8-12% reduction reported from prospective American studies.29 Triglyceride concentration was a risk factor for coronary artery disease after adjustment for age and sex, but it was not an independent risk factor when the other variables were included in the model. This is in accord with other studies, possibly because of the greater biological variability of triglyceride than high density lipoprotein cholesterol measurements.30 However, we found over 6 months that the concentration of high density lipoprotein cholesterol was more variable than that of triglyceride, possibly because of less precision with the assay (coefficient of variation 6% v 2%) and because patients were receiving dietary advice and had a more uniform dietary intake than in the general population. As control of plasma triglyceride and high density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations is interlinked through lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase activities, it may not be feasible to separate the contributions of triglyceride and high density lipoprotein cholesterol to coronary artery disease. Postprandial triglyceride values may have an additional atherogenic role to the fasting values that were measured.31

Haemoglobin A1c

—There was an increase in risk of coronary artery disease with haemoglobin A1c of >6.2%, the upper range of normal values, in accord with other studies which suggest that glycaemia above the normal range gives an increased risk for macrovascular disease.32,33 If glycation of proteins was a major pathogenic factor for coronary artery disease the increased risk would be expected to be proportional to the degree of hyperglycaemia.34 The study showed an increased risk of 11% for each increment of 1% in haemoglobin A1c, similar to the 10% increase in mortality from ischaemic heart disease for an increment of 1% in haemoglobin A1c reported in Wisconsin.35

Blood pressure

—Increased blood pressure was also a major risk factor for coronary artery disease, with a 15% increased risk for an increase in systolic blood pressure of 10 mm Hg, which was similar to that reported in the general population.36 Increased blood pressure was a major risk factor for fatal myocardial infarction. This could be because hypertension is a major additional burden to the heart when myocardial infarction ensues. The hypertension in diabetes study in 1148 patients in a factorial design is evaluating whether strict blood pressure control will prevent complications.37

Retinopathy—

Retinopathy at diagnosis was not a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in a multivariate analysis, although retinopathy was a risk factor for fatal myocardial infarction when only age and sex were adjusted for. Since both retinopathy38 and microalbuminuria39 are associated with hyperglycaemia and hypertension, which are also risk factors for coronary artery disease, the previously described association of retinopathy and microalbuminuria with subsequent cardiovascular mortality might reflect the longstanding hypertension and hyperglycaemia that induced both macrovascular and microvascular disease.

Risk factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus

Risk factors for development of coronary artery disease in the general population may not apply once diabetes has developed. Obesity and central obesity,40 decreased physical activity,41 and raised insulin concentrations42 provide an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, but in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus we found that none of these were major risk factors. These variables are also risk factors for diabetes,43–45 but this study indicates that once diabetes has developed, hypertension, increased concentrations of low density lipoprotein or decreased concentrations of high density lipoprotein cholesterol and hyperglycaemia measured at baseline are greater risk factors for coronary artery disease than these precipitating factors.

Syndrome X, the association of raised concentrations of glucose, insulin, and triglyceride, decreased concentrations of high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and increased blood pressure, describes a combination of previously reported risk factors for coronary artery disease.46 In the general population the combination of upper body obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridaemia, and hypertension has been termed the deadly quartet.47 However, a quintet of increased concentrations of low density lipoprotein and decreased concentrations of high density lipoprotein cholesterol, hypertension, hyperglycaemia, and smoking is probably more relevant in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure.

Estimated hazard ratios for significant risk factors for coronary artery disease occurring in 335 out of 3055 diabetic patients (expressed as floating absolute risks)

Acknowledgments

The cooperation of the patients and many NHS and non-NHS staff at the centres is much appreciated. We thank Professor Eva Kohner, Mr Steve Aldington, Ms Ivy Samuel, and Mrs Caroline Wood for help with the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: This study received grants from the Medical Research Council; British Diabetic Association; the Department of Health; the National Eye Institute and the National Institute of Digestive, Diabetes and Kidney Disease in the National Institutes of Health, United States; the British Heart Foundation; the Health Promotion Research Trust; Charles Wolfson Charitable Trust; the Alan and Babette Sainsbury Trust; the Clothworkers’ Foundation; Oxford University Medical Research Fund Committee; and pharmaceutical companies, including Novo-Nordisk, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Hoechst, Lilly, Lipha, and Farmitalia Carlo Erba. Additional funding came from Boehringer Mannheim, Becton Dickinson, Owen Mumford, Securicor, Kodak, and Cortecs Diagnostics.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Garcia MJ, McNamara PM, Gordon T, Kannell WB. Morbidity and mortality in diabetics in the Framingham population. Sixteen year follow-up. Diabetes. 1974;23:105–111. doi: 10.2337/diab.23.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panzram G. Mortality and survival in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1987;30:123–131. doi: 10.1007/BF00274216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Group. UKPDS 17. A nine-year update of a randomized, controlled trial on the effect of improved metabolic control on complications in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:136–145. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-1_part_2-199601011-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12 year cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:434–444. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gall MA, Borch-Johnsen K, Hougaard P, Nielsen FS, Parving HH. Albuminuria and poor glycaemic control predict mortality in NIDDM. Diabetes. 1995;44:1303–1309. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.11.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuusisto J, Mykkänen L, Pyörälä K, Laakso M. NIDDM and its metabolic control predict coronary heart disease in elderly subjects. Diabetes. 1994;43:960–967. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.8.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontbonne A, Eschwège E, Cambien F, Richard JL, Ducimetière P, Thibult N, et al. Hypertriglyceridaemia as a risk factor of coronary heart disease mortality in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes. Results from the 11-year follow-up of the Paris Prospective Study. Diabetologia. 1989;32:300–304. doi: 10.1007/BF00265546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uusitupa MI, Niskanen LK, Siitonen O, Voutilainen E, Pyörälä K. Ten-year cardiovascular mortality in relation to risk factors and abnormalities in lipoprotein composition in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Diabetologia. 1993;36:1175–1184. doi: 10.1007/BF00401063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler WJ, Ostrander LD, Carman WJ, Lamphiear DE. Mortality from coronary heart disease in the Tecumseh study. Long-term effect of diabetes mellitus, glucose tolerance and other risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:541–547. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyden S, Heiss G, Bartel AG, Hames CG. Sex differences in coronary mortality among diabetics in Evans County, Georgia. J Chronic Dis. 1980;33:265–273. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(80)90021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laakso M, Lehto S, Penttila I, Pyörälä K. Lipids and lipoproteins predicting coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Circulation. 1993;88:1421–1430. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Law MR, Wald NJ, Wu T, Hackshaw A, Bailey A. Systematic underestimation of association between serum cholesterol concentration and ischaemic heart disease in observational studies: data from the BUPA study. BMJ. 1994;308:363–366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6925.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, Isles CG, Lorimer AR, MacFarlane PW, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1301–1307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Group. UKPDS VIII. Study design, progress and performance. Diabetologia. 1991;34:877–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organisation. International classification of procedures in medicine. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 16.United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Group. UKPDS XI. Biochemical risk factors in type 2 diabetic patients at diagnosis compared with age-matched normal subjects. Diabetic Med. 1994;11:534–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Population Censuses and Surveys Office. Mortality statistics: review of the registrar general on deaths in England and Wales. London: HMSO, 1994.

- 18.Coleman MP, Herman C, Douglas A. Person-years (PYRS): a FORTRAN program for cohort study analysis. Lyons: International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1989.

- 19.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Series B. 1972;34:187–201. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Easton DF, Peto J, Babiker AG. Floating absolute risk: an alternative to relative risk in survival and case-control analysis avoiding an arbitrary reference group. Stat Med. 1991;10:1025–1035. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Haffner SM, Pyörälä K, Kallio V, Laakso M. Dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia predict coronary heart disease events in middle-aged patients with NIDDM. Diabetes. 1997;48:1354–1359. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.8.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walters DP, Gatling W, Houston AC, Mullee MA, Julious SA, Hill RD. Mortality in diabetic subjects: an eleven-year follow-up of a community-based population. Diabetic Med. 1994;11:968–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1994.tb00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kannel WB, Wilson PW. An update on coronary risk factors. Med Clin North Am. 1995;79:951–971. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Law MR, Wald NJ, Thompson SG. By how much and how quickly does reduction in serum cholesterol concentration lower risk of ischaemic heart disease? BMJ. 1994;308:367–372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6925.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austin MA, Breslow JL, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Willett WC, Krauss PM. Low-density lipoprotein subclass patterns and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1988;260:1917–1921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawamura M, Heinecke JW, Chait A. Pathophysiological concentrations of glucose promote oxidative modification of low density lipoprotein by a superoxide-dependent pathway. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:771–778. doi: 10.1172/JCI117396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pyörälä K, Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J. The effect of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin on coronary artery diseases in diabetic patients with cornary heart disease. Diabetes. 1995;44(suppl):35. A. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, Neaton JD, Castelli WP, Knoke JD, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective American studies. Circulation. 1989;79:8–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schectman G, Sasse E. Variability of lipid measurements: relevance for the clinician. Clin Chem. 1993;39:1495–1503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stensvold I, Tverdal A, Urdal P, Graff-Iversen S. Non-fasting serum triglyceride concentration and mortality from coronary heart disease and any cause in middle aged Norwegian women. BMJ. 1993;307:1318–1322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6915.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarrett RJ, Keen H. Hyperglycaemia and diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1976;2:1009–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90844-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folsom AR, Szklo M, Stevens J, Liao F, Smith R, Eckfeldt J. A prospective study of coronary heart disease in relation to fasting insulin, glucose, and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:935–942. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brownlee M. Glycation products and the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:1835–1843. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.12.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein R. Hyperglycemia and microvascular and macrovascular disease in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:258–268. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, Collins R, Sorlie P, Neaton J, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1. Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990;335:765–774. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hypertension in Diabetes Study Group. HDS 4: therapeutic requirements to maintain tight blood pressure control. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1554–1561. doi: 10.1007/s001250050614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stratton IM, Kohner E, Aldington S, Matthews DR, Turner RC. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy at diagnosis of non-insulin dependent diabetes in 2964 white Caucasian patients and association with hypertension, hyperglycaemia and impaired beta-cell function. Diabetes. 1995;43:S434. [Google Scholar]

- 39.United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Group. UKPDS X. Urinary albumin excretion over 3 years in diet-treated type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetic patients, and association with hypertension, hyperglycaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia. Diabetologia. 1993;36:1021–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Byers T. Body weight and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:723–724. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509143331109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manson JE, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Hankinson SE, et al. Body weight and mortality among women. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:677–685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509143331101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desprès JP, Lamarche B, Mauriège P, Cantin B, Dagenais GR, Moorjani S, et al. Hyperinsulinemia as an independent risk factor for ischemic heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:952–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604113341504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Modan M, Karasik A, Halkin H, Fuchs Z, Lusky A, Shitrit A, et al. Effect of past and concurrent body mass index on prevalence of glucose intolerance and type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes and on insulin response. The Israel study of glucose intolerance, obesity and hypertension. Diabetologia. 1986;29:82–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00456115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desprès JP, Moorjani S, Lupien PJ, Tremblay A, Nadeau A, Bouchard C. Regional distribution of body fat, plasma lipoproteins, and cardiovascular disease. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:497–511. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manson JE, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Krolewski AS, et al. Physical activity and incidence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. Lancet. 1991;338:774–778. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90664-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reaven GM. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–1607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaplan NM. The deadly quartet. Upper-body obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1514–1520. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.7.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]