Henry Laurens Bio - Charles Pinckney National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service) (original) (raw)

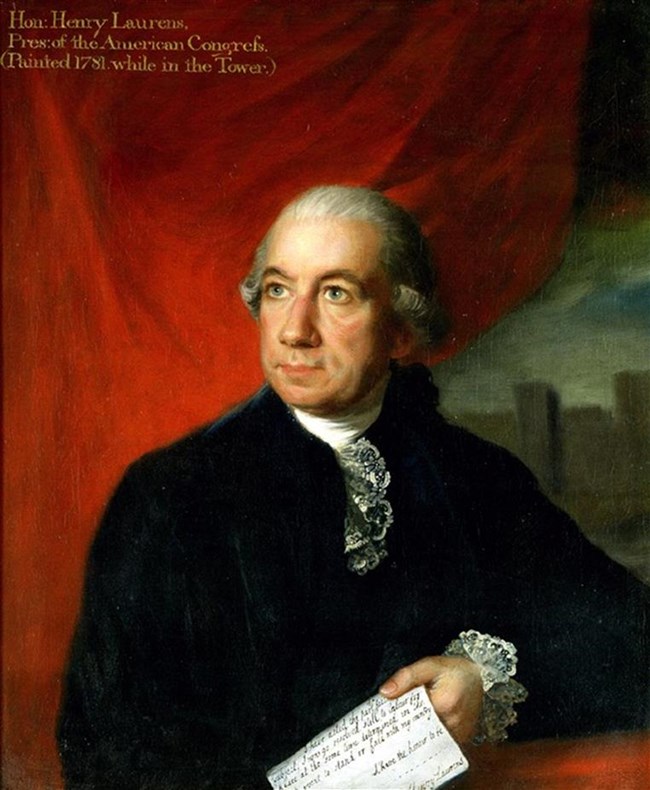

A portrait of Henry Laurens, painted in 1781 or 1784 by Lemuel Francis Abbott. (U.S. Senate)

U.S. Senate

Henry Laurens – “His story is at the core of colonial South Carolina and wrought with intrigue, a conflicting moral compass, family, loyalty, and a fierce passion for American Independence.” (1)

Henry Laurens was born in Charles Town in 1724. He was the grandson of French Huguenot immigrants who were members of the Reformed Church that was established by John Calvin in 1550. They fled to England and then Ireland after the revocation of the Treaty of Nantes and finally immigrating to New York City. In 1715, the Laurens family settled in Charles Town where they became very wealthy.

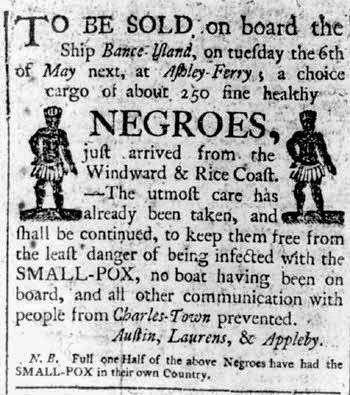

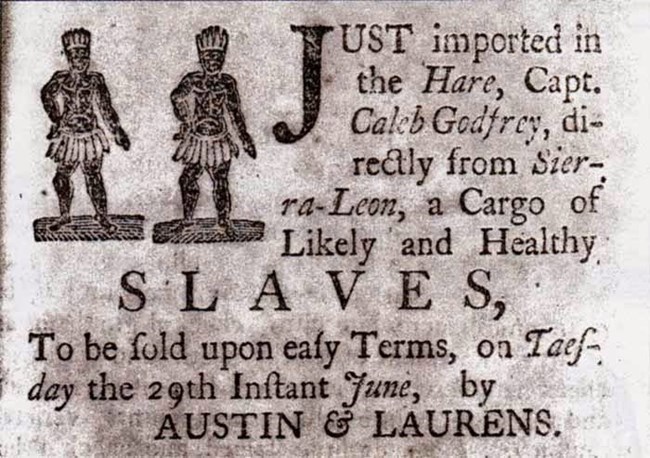

Henry, the first son in the family, was educated in Charles Town and worked in a local counting-house. He was sent to England by his father to learn a trade. He trained under a prominent British merchant. He returned to South Carolina in 1747. At this time, planters were able to ship their rice directly to ports south of Cape Finisterie in Spain. For a while, made Charles Town the busiest port in America. In 1748 Henry opened an import export business in Charles Town, called Austin and Laurens. They imported rum and British mercantile goods. He made contacts while in London such that he entered the slave trade with Grant, Oswald & Company (the company that controlled the slave outpost Bunce Castle located in Sierra Leone). His company contracted to receive, catalog and market slaves by conducting public auctions in Charles Town. They handled the sale of over 8,000 Africans. For this the company received 10% commission on slave cargoes. The expenses incurred while providing for the slaves between landing and the sale and accountability for debts were the responsibility of Austin and Laurens. They were expected to remit accounts after the sales were made regardless of when they were actually paid. They allowed planters up to six months to pay them. Laurens reported netting between 8% and 9% from his share of the sales of slave cargoes. The firm also traded in Carolina Gold rice, indigo and deerskins, tar, pitch, silver and gold. They also sent Colonial merchandise to England on returning ships.

In 1755 Henry wrote to another business, Smith & Clifton, explaining in depth what local planters looked for in slaves. The following is an excerpt:

very likely healthy People, Two thirds at least Men from 18-25 Years old, the other young Women from 14-18 the cost not to exceed Twenty five Pounds Sterling per head... There must not be a Callabar* [sic] amongst them. Gold Coast and Gambias are best, next to them the Winward Coast are prefer'd to Angolas. We would not choose them sent in the Hurricane Season but rather to come in the months of October or November. Pray observe that our people like tall Slaves best for our business and strong withall. Such as small, meager or other ways ordinary won't sell better here than with you. The difference in price between Men and Women is never less than £ 3 Sterling per head, sometimes £ 6.

* Callabar was a port in Nigeria.

Newspaper advertisements posted by Austin & Laurens

Henry was a slave merchant documented to have been involved in the sale of over 68 cargoes of slaves, but in correspondence with family and friends questioned the morality of slavery.

To his son John in 1776:

I told you in my last that I was going to Georgia. . . My negroes there, are all to a man, are strongly attached to me — so are all of mine in this country [South Carolina]; hitherto not one of them has attempted to desert; on the contrary, those who are more exposed hold themselves always ready to fly from the enemy in case of a sudden descent…You know, my dear son, I abhor slavery. I was born in a country where slavery had been established by British kings and parliaments, as well as by the laws of that country ages before my existence. I found the Christian religion and slavery growing under the same authority and cultivation. I nevertheless disliked it…I am not the man who enslaved them; they are indebted to English for that favour; nevertheless I am devising means for manumitting many of them, and for cutting off the entail of slavery. Great powers oppose me — the laws and customs of my country, my own and the avarice of my countrymen (5).

Despite this sentiment he never spoke publicly against slavery and continued in the business until 1770.

Newspaper advertisements posted by Austin & Laurens

By 1750, Laurens had earned enough money to win the hand of Eleanor Ball. They were married on June 25, 1750. Eleanor had 12 children but only four survived past childhood. John Laurens was born October 28, 1754, Martha Laurens “Patsy” was born November 3, 1759, Henry Jr. “Harry” was born July 23, 1763 and Mary Eleanor “Polly": was born April 26, 1770.

Henry Laurens' political career began when he became a member of the Commons of House of Assembly in 1757. Subsequently, he was a member every session but one, until the American Revolution. The Assembly was the dominant institution in Colonial South Carolina.

Henry held the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the South Carolina Militia from 1757- 1761 engaging in many campaigns against the Cherokee Indians and in the French and Indian War. His business contributed £7,000 toward the war against the Cherokee. During this time he kept a diary which survives to this day and is archived as original manuscript in the South Carolina Archives. In 1758, he was appointed to oversee Charles Town defenses as "Commissioner of Fortification." In 1761, Henry was designated to accompany the Cherokee to the capitol for a peace treaty.

Austin and Laurens dissolved in 1762 when Henry's partners moved to England. He continued in the trade without the partnerships. During that time he paid duties on 7 cargoes of slaves as well as other import/export items.

In 1762 Henry purchased the 3,000 acre Mepkin Plantation, located 30 miles from Charles Town, for £8,000. Fifty slaves farmed and cultivated corn, indigo and wheat. In 1765, Laurens began acquiring and managing more rice and indigo plantations in South Carolina and along the Georgia coast. In total he acquired around twenty thousand acres. By 1766 he owned 227 enslaved persons in all of his holdings.

Henry Laurens declined an appointment to the Kings Council in Carolina in 1764 and again in 1768 (2). With these decisions he began to separate himself from British politics. In October of 1765, the Laurens Family was personally affected by the animosity toward the Stamp Act. The Stamp Act was opposed at a local level by the colonist who thought that they were being taxed without representation, although Laurens urged peaceful compliance until the law could be repealed. When the stamps arrived in Charles Town they were deposited at Fort Johnson for nine days while locals hung effigies, stormed and searched houses looking for the stamps. Laurens viewed the Sons of Liberty illegal and extreme and likely to encourage harsher measures from Parliament. It was rumored that Lieutenant William Bull was afraid there would be an attack on the fort so he moved the stamps to the home of a local gentleman. It was thought this was Henry Laurens so a mob at midnight on October 25th stormed the Laurens' home.The confrontation lasted 75 minutes and he was amazed that so many men, many drunk and all armed did no damage to his house or his grounds.

As a merchant Henry was critical of the British involvement in the Colonial economy. He frequently filed lawsuits with Crown judges and consequently had an excellent understanding of British Maritime Law. He became embroiled in a controversy with Charles Town custom agents that lasted from 1767 to 1769 over the confiscation of three of his family’s vessels.

Henry's wife, Eleanor, died in the Spring of 1770, four weeks after the birth of their daughter (Mary Eleanor). Henry dealt with his grief by taking his sons to England to complete their education leaving the girls with his brother James in Charles Town. They later moved the young Laurens women to London and then to France.

While in England, in 1774 he was one of thirty-eight Americans who signed the Boston Port Bill petition, which opposed the Tea Act. The Tea Act was passed and closed the port of Boston and demanded that the colonists make reparations for the tea that was dumped into the harbor during the Boston Tea Party.

Henry returned to Charles Town in November of 1774.

The following year he was appointed to the Safety Council and acting as President he used his influence to hold back any unnecessary provocations. He also accepted the job of Chairman of the Charles Town General Committee and President of Provincial Congress. Despite these sentiments of the time, Laurens held out hope that reconciliation could still be made with Britain. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney chaired the group that drew up the temporary Colonial/State Constitution that consisted of Henry Laurens, Charles Pinckney and eight others. On March 26, 1776 South Carolina became the second colony to adopt a new Constitution. John Rutledge was elected President and Henry Laurens the Vice President.

From July 1777 until 1779, he represented South Carolina in the Continental Congress. When John Hancock resigned in 1777, Laurens became President of the Continental Congress. He served on the Commerce Committee and the Treasury Board. For over two weeks in December of 1777, he suffered so much with his gout that he was unable to attend Congress. He conducted business from his bed. Although he offered to resign for medical reasons his offer was denied. During the debate on the Saratoga Convention, he was the only South Carolina delegate in town and had to be carried into the chambers because he was so ill.

When France entered the war, Laurens decided to remain in Congress as he worked hard to establish trade contracts with French businesses but did so with caution as he did not find French motives trustworthy.

In March 1778 his seat in Congress was taken over by William Henry Drayton. In November he attempted to vacate the Presidency but the House voted unanimously to ask him to stay until the Articles of Confederation were accepted by all the States.

Laurens felt bound to stay in Congress when his fellow delegate William Henry Drayton died leaving him the sole representative from South Carolina. This decision made him available to be elected on October 21, 1779 to travel to the Hague to negotiate a loan of not more than 10 million dollars. In addition on November 1, 1779 he was elected as Minister to negotiate a treaty of amity and commerce with the Netherlands. His salary for this mission would be £ 1,500 silver.

During his travels to the Netherlands he was sent to England to be questioned by British police authorities. He was charged with suspicion of high treason after they confirmed his identity and presented the paper that commissioned him to borrow money from countries in Europe to be used by Congress. He was then committed to the Tower of London. He is the only American to have ever been held prisoner there.

On October 13, 1780, he received his first visitors. It is documented in the Tower's Register that the members of his family were allowed to visit every ten days to two weeks thereafter. He was not allowed to leave his room until November 7 and walk the grounds with guards; during this first walk, bars were installed on the windows. While a prisoner he wrote articles for a rebel newspaper with pen and paper provided by a woman who smuggled them in to him, and then smuggled the articles out of the prison for him.

In April of 1781, his son John arrived in Paris on the behalf of Congress to serve as a special envoy to King Louis XVI of France to appeal for supplies for the relief of American armies. While there he appealed to the French Government to intervene for the release (or at the very least the better treatment) of his father. When John reported to Congress he suggested that if America treated a high value British prisoner similarly, a prisoner exchange might be possible.

On June 14, 1781 the President of the Continental Congress informed Benjamin Franklin (the plenipotentiary of the United States at the Court of Versailles) that he was authorized to offer Lieutenant General Burgoyne, a British prisoner of war, in exchange for Henry Laurens. He was officially discharged with a full and unconditional release on April 27, 1782. He had spent 15 months as a prisoner in the Tower, not of war but as a prisoner of Great Britain since he was deemed a traitor. Whereas he was not a prisoner of war, he could not be traded for another prisoner until the capture of General Cornwallis who was the Constable of the Tower. It was January of 1782 when General Cornwallis, who was paroled by America in exchange for Henry Laurens, arrived in England. It was supposed to absolve and discharge Laurens from his parole when he was released.

Henry Laurens had not been home long when his youngest daughter, Mary Eleanor, sought his approval for marriage at the age of sixteen. He was not so pleased with the decision of his youngest daughter, Mary Eleanor, to marry, nor, one might suspect, with her choice of a partner. … In 1786 at the age of sixteen, she asked her father for permission to marry Charles Pinckney, the rising young politician who would play an important role in the federal Constitutional Convention, contribute to the founding of the Jeffersonian Republican party in South Carolina, and serve four terms as governor of the state. Laurens objected to the match on the apparent grounds of the youth of his daughter and because she was thirteen younger than Pinckney, though one suspects that political differences might also have played a role. Laurens managed to delay this marriage for two years, but finally relented and witnessed the marriage of the couple upon her eighteenth birthday in 1788.

When the Constitution was passed in 1787, Henry agreed to serve in Charleston to ratify it on May 23, 1788. South Carolina was the eighth state to ratify with a vote of 149 to 73.

Henry Laurens served as a Presidential Elector for South Carolina when under the first U.S. Presidential election in 1789, he cast South Carolina's vote for General George Washington. After this vote he was officially retired from all politics and spent the rest of his life at Mepkin Plantation concentrating on his agriculture endeavors.

Laurens was aging and his illness was increasingly affecting his ability to travel. Henry had a fear of being buried alive that was inspired by the false declaration of death of his daughter Martha when she was a child. He created a solution to his fear and after passing on December 8, 1792, he was cremated. This marked the first cremation of a major political figure in the United States. His ashes were buried next to his son, John, at Mepkin Plantation.

Henry Laurens lived in a dynamic time. The beginning of his life and business were under British rule. The contacts that he made in England were very beneficial to him not only monetarily but also in the form of favors later on in his life. He felt the repercussions of the tightening of British rules as the Colonies were attempting to break away from Britain. He held for a long time that things could be worked out but finally conceded that change was inevitable. He supported the Revolution in a political role. He would spend more than half of his life (42 years) in political service. He suffered much through those years; loss of family members, illness, ruin of his estates, being held prisoner in another country but through all of the changes and losses he persevered to help ensure that this new country was established, the United States of America.

Sources

1. www.scnhc.org/story/a-revolutionary-profile-henry-laurens

2. www.friendsoffortLaurens.org

3. www.henrylaurens.com

4. McDonough, Daniel J. Christopher Gadsden and Henry Laurens: The Parallel Lives of Two American Patriots (Susquehanna University Press, 2001) ISBN-10: 157591039X

5. http://civilaref.blogspot.com/2014/10john-laurens-born-october-28-1754.html

6. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/guidedisplay.pl?index=L000121 Laurens, Henry

7. https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/09/henry-laurens-15-months-in-the-tower/

8. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/art/artifact/Painting\_31\_00010.htm

9. https://www.sc.edu/uscpress/books/1996/laurens.html