History of Liepāja (original) (raw)

Courland-Semigallia imperial port (1625-1795)

Liepāja was born out of a wish of a small Duchy of Courland and Semigallia to become a major naval power. For this it needed ports, and Liepāja located on a great location between sea and lake was granted city rights in 1625. Ships left its shores to colonize Gambia and Tobago, while the port was constantly expanded (in 1697 artificial lake-to-sea shipping canals have replaced a local river). While the majority of Courland-Semigallia population was ethnically Latvian, its leadership and elite were German. As such, the new Liepāja was overwhelmingly German, who called the city Libau.

Liepāja in 1701, looking from the sea. The seashore was occupied by a large fortress (later replaced by a district of wooden villas), while the town itself stood further inland (closer to the lake). The shipping channel that connected sea with the lake is already visible. New Liepāja was not yet built.

The plan of colonization may have been too big for the small Duchy. After losing multiple wars, Courland-Semigallia had to relinquish its American and African colonies in the 18th century and ceased to be a naval power. Liepāja’s importance plummeted together with that of its owner-state, which slowly came under Russian influence.

Westernmost city of the Russian Empire (1795-1918)

In 1795 Russia annexed Courland-Semigallia, acquiring Liepāja. However, little did actually change in the city for another half a century. Ethnic Germans retained the majority (still at 63% in 1863) while the growth was slow.

Local German newspaper of 1890.

All that started to crumble as railway reached Liepāja (1871), allowing development of factories. Liepāja expanded as Russia’s westernmost port. It received a direct steamship service to New York and was used for cargo export. It was the starting point of Russia-USA Transatlantic telegraph (est. 1906). The population increased from 10000 in 1863 to 84000 in 1911.

New York-bound steamship in Liepāja port in 1900. Some 500 000 Russian Empire’s people emigrated to USA using this line. In some years the annual migrant flow surpassed Liepāja population.

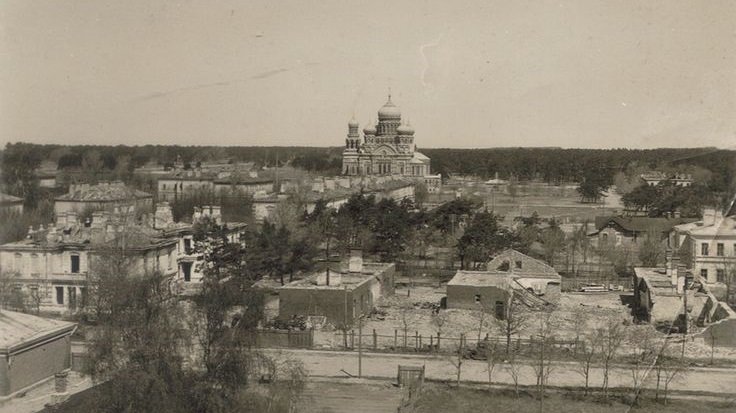

The “unsafe” location of what has by now become an important city troubled the Russian czar (German border was merely 70 km to the south). In 1890 he commissioned an unprecedented all-new naval military city north of Liepāja-proper. Now known as “Karosta” the military port had its own splendid Russian Orthodox church, multiple fortifications, a shipping canal spanned by a rotating bridge, pigeon mail station and even an internal narrow gauge railway. Numerous red barracks were the staple housing for Russian soldiers and officers.

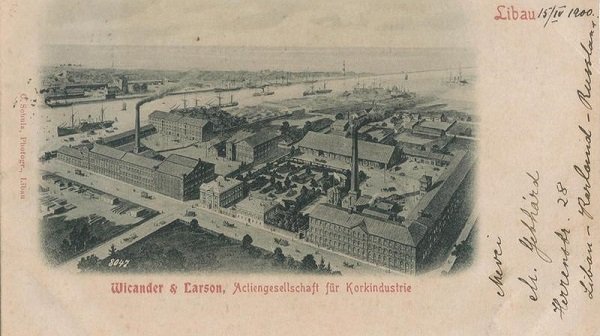

Wicander and Larson cork factory in 1900 Liepāja.

The new seat of Russia’s military might did little to prevent the societal changes that ultimately led to the demise of Russian rule over Latvia. Latvians were moving into Liepāja in massive numbers from nearby villages to staff the burgeoning industry. Their population share increased from 16% in 1863 to 43% in 1911. After becoming more educated and imbibed in the urban lifestyle, Latvians started to treat their own culture and language with respect, demanding more rights (or even independence) for their nation.

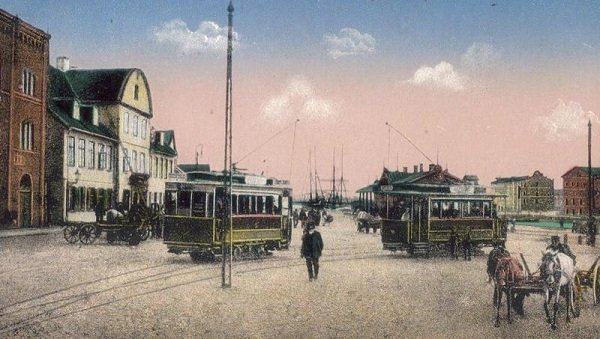

Electric trams in 1910 Liepāja.

In fact, Liepāja was at the epicentre of not one, but two national awakenings. Located next to Lithuanian ethnic lands (also Russian-ruled at the time) the city attracted thousands of Lithuanians for work and educational opportunities (which were limited back in Lithuania due to Russia’s anti-Lithuanian and anti-industrial policies there). Some estimates claim that on the eve of World War 1, Lithuanians made up to a quarter (25%) of the entire Liepāja’s population. Lithuanians who had graduated from Liepāja gymnasium participated heavily in their own Lithuanian National Awakening. Many key figures of the early 20th century Lithuania had spent their formative years in Liepāja.

A Lithuanian choir in Liepāja. In Baltic countries where Song Festivals are massively important, choirs were among key pillars of ethnic identity

Interwar Latvia’s 2nd city (1918-1940)

World War 1 gave the opportunity to realize the goals of both national revivals as Germany and Russia were defeated. Lithuania and Latvia declared independence in 1918. While there was a brief dispute on which country should receive Liepāja, arbitration ruled in favour of Latvia (1922). The city even briefly served as Latvia’s capital while Riga was occupied by Russians during the Latvian War of independence.

Karosta naval military city after taking damage during World War 1.

Thousands of Lithuanians, Poles and Russians left for their own now-separate homelands, bringing Liepāja’s population down to 50000 by 1925.

Pretty but somewhat empty Graudu iela in Liepāja (1920).

Germans largely remained as they always did, but by the 20th century, they were already a spent force as there were no rural Germans who would migrate into the city. Therefore German share declined every year as non-Germans poured in. By 1925 it was already down to 10%. On the other hand, the numbers of Latvians grew constantly. By 1935 Liepāja was 68% Latvian with a total population of 57000; it became Latvia’s second largest city.

Mostly ethnic Latvian college students parading in Liepāja of 1939.

Forbidden Soviet military city (1940-1990)

World War 2 brought a major upheaval to Liepāja. German population was destroyed due to Soviet occupation (who had also killed many Latvians) while the Jewish population (13% in 1935) was decimated by Nazi German occupation.

Jews held on beach under the Nazi German occupation before a massacre.

Those who died were swiftly replaced by people from the Soviet Union, especially ethnic Russians. By 1959 Liepāja was already larger than before WW2 (71000 inhabitants). By 1979 Russians became the largest ethnic group in the city. Liepāja’s population peaked at 114000 in 1989 (at the time, merely 38,8% of locals were Latvians and 43,1% were Russians).

Soviet buildings of Liepāja covered in propaganda slogans

Additionally, Soviets have repopulated the old Russian Imperial Karosta naval base, staffing it with 26000 soldiers and officers (this was one-fourth of Liepāja’s inhabitants). As every Soviet city of military importance, Liepāja was closed: no person from outside city limits could have visited it without a government permit.

A festival of naval soldiers in Karosta canal during Soviet occupation

As Liepāja used to be a comparably large city even before World War 1, relatively little expansion was needed. Only a few Soviet districts were added, helping Liepāja retain that “old wooden city” atmosphere of the 19th-century industrial boom. Slower growth led Liepāja to lose the status of Latvia’s second largest city to Daugavpils.

A Soviet clinic

Modern Liepāja seeks identity (1990-)

The restoration of Latvia’s independence (1990) led to the final departure of Russian soldiers and officers by 1994. This was especially welcomed by Liepāja’s citizens. However, it once again sent the population on the decline (89000 in 2000). Many of the Liepāja’s old buildings were abandoned. This was especially true in Karosta, the proportions of which were meant to serve a massive empire rather than a small Latvian navy. The “naval military city” became nearly entirely abandoned, its red barracks slowly crumbling into oblivion.

In order to revitalize the city, a free economic zone was established in 1997, attracting businesses from abroad. New tourist attractions were opened, gentrifying the main canal shoreline and even (somewhat) the Karosta, which became a popular location for dark tourism.

Given its reclaimed Latvian plurality (49,4% in 2000, a larger share than in either Riga or Daugavpils) the city was believed to be especially livable by ethnic Latvians. However, it was plagued by difficult access. Latvia’s lack of highways mean that some 3 hours are needed to go to Riga; the attempts to open Liepāja airport for passenger traffic failed while Liepāja port is behind those of Riga and Ventspils.

An Air Baltic plane in Liepāja airport in 2008. Flights to Riga, Hamburg, Copenhagen and Moscow were then operated, but later cancelled