How do we break the filter bubble, and design for democracy? (original) (raw)

Yui Mok PA Archive/PA Images. All rights reserved.In the aftermath of the US presidential election that seemed to shock at least half the country, many liberals are asking themselves how they missed the popularity of Donald Trump. The ‘remain’ campaign for the UK’s shocking Brexit vote are also asking themselves how the other side won. One possible answer lies in a concept known as “the filter bubble”: the idea that personalisation tools from companies like Facebook and Google are isolating us from opposing viewpoints, leading different parties to feel like they occupy separate realities. The theory argues that this in turn decreases the quality of information and as a consequence, civic discourse and democracy is undermined.

To investigate this theory, Facebook conducted a study in 2015, and its findings show that exposure to diverse content is suppressed by Facebook’s algorithm by 8% for self-identified liberals, and by 5% for self-identified conservatives. As critics argue, this proves that users see fewer news items on Facebook that they disagree with which are shared by their friends, because the algorithm is not showing them.

While Facebook and Google have been criticised because they cause filter bubbles and damage democracy, algorithms are not inherently bad. Some designers have developed software that actually combat filter bubbles. However, as I will demonstrate, how the designers interpret democracy shapes the tools they are developing. Metrics from liberal and deliberative notions of democracy are dominating most of the tools, and other metrics, such as ‘minority reach’ are not implemented by any of the tools.

Liberal democracy and autonomy-enhancing tools

Liberal democrats stress the importance of self-determination, awareness, being able to make choices and respect for individuals. They construe democracy as an aggregation of individual preferences through a contest (in the form of voting), so that the preferences of the majority win the policy battle. Filter bubbles are a problem for liberal democrats, especially due to restrictions on individual liberty and autonomy, restrictions on choice and the increase in unawareness.

If Facebook and Google make decisions on our behalf, and provide us no options to control the information we are receiving, this is bad for the individual, according to liberal democrats.

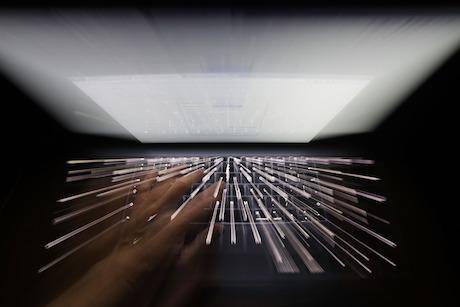

There are many tools developed with this notion of democracy, where metrics such as autonomy, awareness and choice are used. One of the first examples of such tools is Balancer (See Figure 1). It is a Google Chrome extension that analyses user’s web browsing history and shows the user the political slant of their reading history. A more recent example is PolitEcho (Figure 2). PolitEcho shows the user the political biases of their Facebook friends and news feed. The tool assigns each of the friends a score based on a prediction of their political leanings, then displays a graph of the friend list. It calculates the political bias in the content of the user’s own news feed and compares it with the bias of the friends’ list, to highlight possible differences between the two.

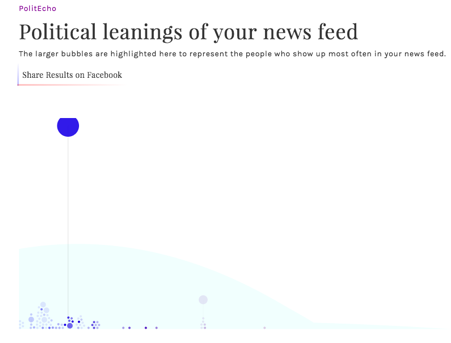

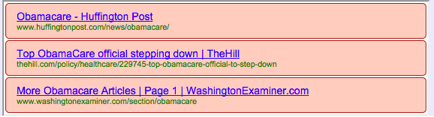

Bobble (Figure 3) uses hundreds of nodes to distribute a user's Google search queries worldwide each time the user performs a Google search. For example, when a user performs a Google search with keyword “Obamacare", this search keyword is distributed to 40+ worldwide Bobble clients that perform the same Google search and return corresponding search returns. Users then can see which results are displayed on their browser, but not on others, and vice versa. It is a tool for users to get an idea of the extent of personalisation taking place. The tool aims to increase users’ awareness of Google’s filters.

Figure 1: Balancer is a browser add-on that shows users their biases. In this picture the user is biased towards reading from liberal news outlets. Figure 2: PolitEcho shows the political leanings of friends and the political leaning of shown posts in a user’s Facebook news feed. Figure 3: Bobble displays a user’s Google search results that only they received (in yellow) and results that they have missed but others have received (in red).

Deliberative democracy and knowledge quality enhancing tools

Deliberative democrats aim to create a public opinion through open public discussions, so that elections are infused with information and reasoning. The goal is to use the common reason of equal citizens, not just fair elections. Improving the quality of information, discovering disagreements, gaining mutual understanding and sense-making are among their other goals.

Filter bubbles are a problem for deliberative democrats, mainly because of the low quality of information and the diminishing of information diversity. If bubbles exist, the pool of available information and ideas will be less diverse and discovering new perspectives, ideas or facts will be more difficult. If we only get to see the things we already agree with on the Internet, discovering disagreement and the unknown will be quite difficult, considering the increasing popularity of the Internet and social media as a source of political information and news. Our arguments will not be refined, as they are not challenged by opposing viewpoints. We will not contest our own ideas and viewpoints and as a result, only receive confirming information. This will lead us not to be aware of disagreements. As a consequence, the quality of arguments and information and respect towards one other will suffer. Respect for other opinions is decreased and civic discourse is undermined,

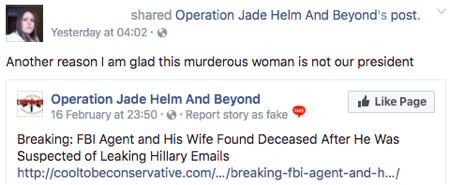

There are many tools developed with this notion of democracy, where metrics such as information quality, disagreement discovery, mutual understanding are used. An example of such a tool is “This is fake” (Figure 4). “This is fake” allows users to submit items that intentionally spread misinformation. After a moderator reviews the submission, it is added to a database and users are warned when the item shows up in their feed. While the tool does not aim to highlight disagreements or improve deliberation, it aims to improve the quality of information. Similarly B.S. Detector (Figure 5) identifies fake news, satire, extreme bias, hate group, clickbait sites and adds a warning label to the top of questionable sites as well as link warnings on Facebook and Twitter.

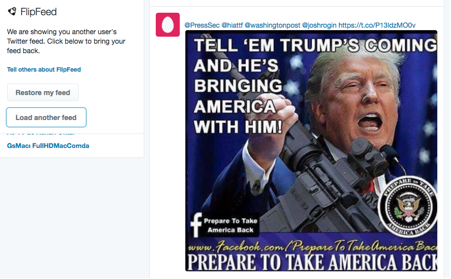

Figure 4: “This is Fake” allows users to submit fake items and warns users about fake items. Figure 5: B.S. Detector warns the user when the site they visit contains conspiracy theories, extreme bias, hate speech, or fake news.FlipFeed (Figure 6) is a Chrome extension that enables Twitter users to replace their own feed with that of another real Twitter user. Powered by deep learning and social network analysis, feeds are selected based on inferred political ideology ("left" or "right") and served to users of the extension. For example, a left-leaning user who uses FlipFeed may load and navigate a right-leaning user's feed, observing the news stories, commentary, and other content they consume. While it does not aim to assess the quality of information, it aims to highlight disagreements and discover other viewpoints.

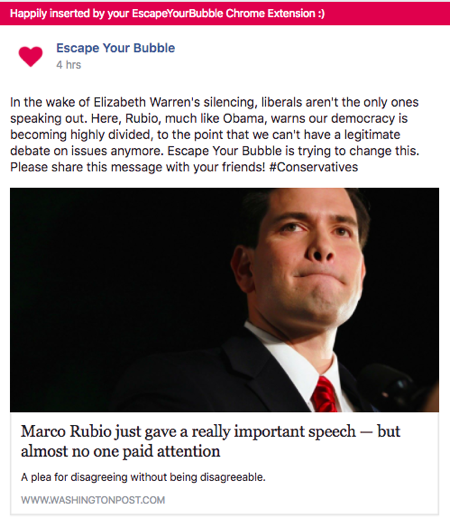

Figure 6: FlipFeed changes a user’s newsfeed with another user’s from the other political ideology (left or right).Escape Your Bubble (Figure 7) asks users to identify whether they want to learn more about Republicans or Democrats and inserts stories into their feeds that align with the political leanings they wish to be exposed to. The extension then adds one clearly marked story that falls outside of the user's established political viewpoint every time a user visits the social network.

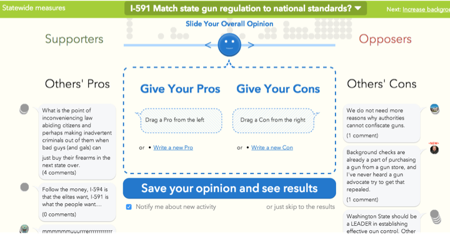

Figure 7: Escape your Bubble, depending on the user’s preferences, inserts articles into their news feed from the opposing viewpoint (republican or liberal). Considerit (Figure 8) is a deliberation (pro/con) tool that is developed with the aims of (1) helping people learn about political topics and possible trade-offs between different opinions, (2) nudging them toward reflective consideration of other voters’ thoughts, and (3) enabling users to see how others consider tradeoffs. It provides an interface where users can create pro/con lists by including existing arguments others have contributed, to contribute new points themselves, and to use the results of these personal deliberations to expose salient points by summarizing their stance rather than a yes/no vote.

Figure 8: Considerit helps people learn about political topics and possible tradeoffs between different opinions.

Are the tools perfect, and what about other models of democracy?

While liberal and deliberative notions of democracy dominate the created tools against filter bubbles, these models are not perfect. The liberal model of democracy is often criticised because it has no way of distinguishing normatively legitimate outcomes from the preferences and the desires of the powerful, and makes no distinction between purely subjective preferences and legitimate and shared (quasi-objective) judgments. It simply aggregates the choices of individuals. Deliberative democracy on the other hand is criticised due to limits of deliberation in large nations, widespread incompetence and political ignorance of an average voter and lack of time for real and frequent deliberation. Furthermore, too much focus on consensus via the deliberation of the majority might not provide much opportunity for the minority/challenging opinions.

There are other models of democracy**.** For instance, agonistic democracy stresses the need to provide special exposure to the needs/opinions of minorities andand those who are disadvantaged due to structural inequalities. Agonists argue that just aiming for consensus and deliberation will serve the interest and perspective of dominant groups. As a result, minorities might never get the chance to reach a larger public.

While it is possible to come across critical voices and disadvantaged views using some of these tools, it is also highly likely that these voices and views get lost among the “popular” items, which are of interest to the majority of the audience. As media scholars argued, media should not only proportionally reflect differences in politics, religion, culture and social conditions, but provide equal access to their channels for all people and all ideas in society. If the population preferences were uniformly distributed over society, then satisfying the first condition (reflection) would also satisfy the second condition (equal access). However, this is seldom the case. Often population preferences tend toward the middle and to the mainstream. In such cases, the media will not satisfy the equal access norm, and the view of minorities will not reach a larger public. This is undesirable, because social change usually begins with minority views and movements.

In conclusion, while the efforts of these designers are laudable, most of the designers’ interpretations of democracy seem to be limited to “increase awareness, increase choice and hear the other side”. As American philosopher John Dewey observed, long before the Internet, social media and other platforms were invented, democracy is an ongoing cooperative social experimentation process. Dewey was of the opinion that we live in an ever-evolving world that requires the continuous reconstruction of ideas and ideals to survive and thrive. The idea of democracy is no exception in this respect. Hence, we should experiment with a plurality of democracy models, including ones that propagate agonistic elements.

What should Google and Facebook do?

Almost all of the tools I have mentioned are developed with limited resources and if they operate on popular platforms such as Facebook or Instagram, there is a risk that they get banned due to unauthorised access. They are also not likely to be used by the majority of Internet users. Google and Facebook often argue that they are not a news platform, they do not have an editorial role and therefore they will not design algorithms to promote diversity. For instance, Facebook’s project management director for News Feed states: “there’s a line that we can’t cross, which is deciding that a specific piece of information – be it news, political, religious, etc – is something we should be promoting. It’s just a very, very slippery slope that I think we have to be very careful not to go down”.

However, research shows that these platforms are dominant social platforms when it comes to news consumption. According to a study from 2016, most people in the US read news from their phones and of those on Facebook, more than two-thirds use it for news. Another recent study indicates that social media has overtaken television as young people's main source of news. Meanwhile, news sites rely more and more on Facebook for social traffic. For instance, in the first quarter of 2016, Buzzfeed received 201,343,000 worldwide desktop visits from Facebook alone. If we also consider the dominant position of these platforms in the search and social media markets worldwide, we can argue that they are indeed important news and opinion sources.

Considering their dominant status, online platforms should adapt and experiment with the metrics and approaches that I have outlined. Breaking bubbles requires an interdisciplinary approach, as several disciplines including human-computer interaction, multimedia information retrieval, and ethics all have something to contribute. More experiments with different contexts will need to be conducted in order to find which techniques work and which do not. Once we have more concrete results, the systems could apply different strategies for different types of users.

An earlier version of this article appeared in Ethics and Information Technology: “Breaking the filter bubble: democracy and design” (E. Bozdag and van den Hoven MJ), 2015.

openDemocracy is partnering with the World Forum for Democracy, exploring the relationship between education and democracy. Read more here.