The rise of networked platforms for physical world services (original) (raw)

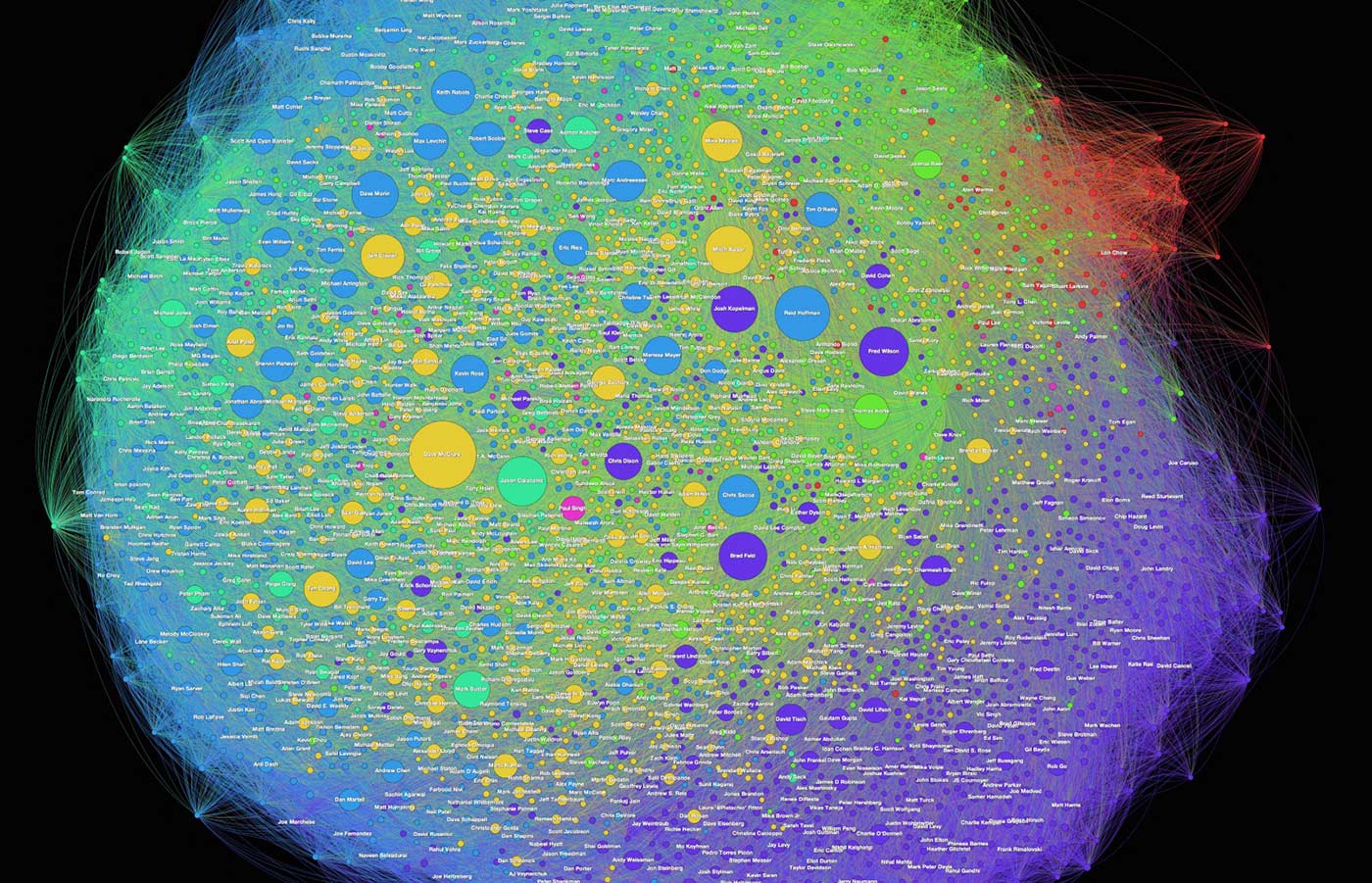

Visualization of the AngelList network by Dave Troy (@davetroy). Copyright 2014 by 410 Networks. Used with permission.

Visualization of the AngelList network by Dave Troy (@davetroy). Copyright 2014 by 410 Networks. Used with permission.

One of the themes we’re exploring at the Next:Economy summit is the way that networks trump traditional forms of corporate organization, and how they are changing traditional ways of managing that organization. Uber and Airbnb are textbook examples of this trend. Uber has ambitious plans to manage hundreds of thousands — eventually even millions — of independent drivers with a small core of employees building a technology platform that manages those workers. Airbnb is on track to have more rooms on offer than large hotel chains, with under a thousand employees.

Esko Kilpi beautifully described the power of networks in an essay on Medium, The Future of Firms, reflecting on economist Ronald Coase’s theory of 20th century business organization. He wrote:

The existence of high transaction costs outside firms led to the emergence of the firm as we know it, and management as we know it. … The reverse side of Coase’s argument is as important: if the (transaction) costs of exchanging value in the society at large go down drastically, as is happening today, the form and logic of economic and organizational entities necessarily need to change! The core firm should now be small and agile, with a large network.

The mainstream firm, as we have known it, becomes the more expensive alternative. This is something that Ronald Coase did not see coming. Accordingly, a very different kind of management is needed when coordination can be performed without intermediaries with the help of new technologies. Apps can do now what managers used to do. [Bolding mine.]

Today, we stand on the threshold of an economy where the familiar economic entities are becoming increasingly irrelevant. The Internet and new Internet-based firms, rather than the traditional organizations, are becoming the most efficient means to create and exchange value.

Of course, networks have always been a part of business. An automaker is not made up of just its industrial workers and its managers, but also of its network of parts suppliers and auto dealerships and ad agencies. Even its shareholders are a network that supports its capital needs. Similarly, large retailers are aggregation points for a network of suppliers, logistics companies, and other suppliers. Fast food vendors like McDonalds and Subway aggregate a network of franchisees. The entire film and TV industry consists of a small core of full-time workers and a large network of temporary on-demand workers. This is also true of publishing and other media companies. My own company, O’Reilly Media, publishes books, puts on events, and delivers online learning with a full-time staff of five hundred and an extended family of tens of thousands of contributors — authors, conference presenters, technology advisers, and other partners.

But the Internet takes the networked firm to a new level. Google, the company that ended up as the prime gateway to the World Wide Web, provides access to a universe of content that it doesn’t own, yet it has become the largest media company in the world. 13- to 24-year-olds already watch more video on YouTube, much of it user-contributed, than they watch on television. And Amazon just surpassed Walmart as the world’s most valuable retailer by offering virtually unlimited selection, including marketplace items from ordinary individuals and small businesses.

On-demand companies like Uber and Airbnb are only the latest development in an ongoing transformation of business by the Internet. In addition to discussing these latest entrants, we’ll take a look at what we learn from the evolution of Internet e-commerce and content marketplaces. Then we’ll try to tease out some best practices of Internet-era platforms and marketplaces.

The evolution of platforms

Consider the evolution of the retail marketplace as exemplified first by chain stores, and then by Internet retailers like Amazon, which have largely replaced a network of small local businesses that delivered goods through retail storefronts. Cost efficiencies led to lower prices and greater selection, drawing more consumers, which in turn gave more purchasing power to larger retailers, allowing them to lower prices further and to crush rivals in a self-reinforcing cycle. National marketing of these advantages led to the rise of familiar chains.

But the Internet added even more leverage, reducing the need to invest in real estate, reaching customers who were not physically close to prime locations, and building in new habits of customer loyalty and instant gratification. With delivery now same day in many locations, anything you need is only a few clicks away.

Internet retailers like Amazon were also able to offer even larger selections of products, aggregating offerings not just from a carefully chosen network of suppliers, but opening up self-service marketplaces in which anyone can offer products. Years ago, Clay Shirky described the move from “filter, then publish” to “publish, then filter” as one of the key advantages brought by the Internet to publishing, but the lesson applies to virtually every Internet marketplace. It is fundamentally an open-ended network in which filtering and curation (otherwise known as “management”) happens largely after the fact.

But that’s not all. While large physical retailers cut costs by eliminating knowledgeable workers, using lower prices and greater selection to hedge against worse customer service (compare an old-time hardware store with a chain like Home Depot or Lowe’s), online retailers did not make these same tradeoffs. Instead of eliminating knowledgeable workers, they replaced them with software.

Even though there are several orders of magnitude more products than in physical stores, you don’t need a salesperson to help you find the right product on Amazon — a search engine helps you find it. You don’t need a salesperson to help you understand which product is the best — Amazon has built software that lets customers rate the products and write reviews to tell you which are best, and then feeds that reputation information into their search engine so that the best products naturally come out on top. You don’t need a cashier to help you check out — software lets you do that yourself.

One way to think about the new generation of on-demand companies, such as Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb, is that they are networked platforms for physical world services, which are bringing fragmented industries into the 21st century in the same way that ecommerce has transformed retail.

Let’s start by taking a closer look at the industry in which Uber and Lyft operate.

The coordination costs of the taxicab business have generally kept it local.According to the Taxicab, Limousine, and ParaTransit Association (TLPA), the US taxi industry consists of approximately 6,300 companies operating 171,000 taxicabs and other vehicles. More than 80% of these are small companies operating anywhere between one and 50 taxis. Only 6% of these companies have more than 100 taxicabs. Only in the largest of these companies do multiple drivers use the same taxicab, with regular shifts. 85% of taxi and limousine drivers are independent contractors. In many cases, the taxi driver pays a rental fee (typically 120/120/120/130 per day) to the owner of the cab (who in turn pays a dispatch and branding fee to the branded dispatch service) and keeps what he or she makes after paying that daily cost. The total number of cabs is limited by government-granted licenses, sometimes called medallions.

When you as a customer see a branded taxicab, you are seeing the brand not of the medallion owner (who may be a small business of as little as a single cab), but of the dispatch company. Depending on the size of the city, that brand may be sublicensed to dozens or even hundreds of smaller companies. This fragmented industry provides work not just for drivers, but for managers, dispatchers, maintenance workers, and bookkeepers. The TLPA estimates that the industry employs a total of 350,000 people, which works out to approximately two jobs per taxicab. Since relatively few taxicabs are “double shifted” (these are often in the largest, densest locations, where it makes sense for the companies to own the cab and hire the driver as a full-time employee), that suggests that half of those employed in the industry are in secondary support roles. These are the jobs that are being replaced by the efficient new platforms. Functions like auto maintenance still have to be performed, so those jobs remain. Jobs that are lost to automation are equivalent to the kinds of losses that came to bank tellers and their managers with the introduction of the ATM.

Technology is leading to a fundamental restructuring of the taxi and limousine industry from one of a network of small firms to a network of individuals, replacing many middlemen in the taxi business with software, using the freed-up resources to put more drivers on the road.

Uber and Lyft use algorithms, GPS, and smartphone apps to coordinate driver and passenger. The extraordinary soon becomes commonplace, so we forget how our first ride was a magical user experience. That magic can lead us to overlook the fact that, at bottom, Uber and Lyft provide dispatch and branding services much like existing taxi companies, only more efficiently. And like the existing taxi industry, they essentially subcontract the job of transport — except in this case, they subcontract to individuals rather than to smaller businesses, and take a percentage of the revenue rather than charging a daily rental fee for the use of a branded taxicab.

These firms use technology to eliminate the jobs of what used to be an enormous hierarchy of managers (or a hierarchy of individual firms acting as suppliers), replacing them with a relatively flat network managed by algorithms, network-based reputation systems, and marketplace dynamics. These firms also rely on their network of customers to police the quality of their service. Lyft even uses its network of top-rated drivers to onboard new drivers, outsourcing what once was a crucial function of management.

It’s useful to call out some specific features of the new model:

- GPS and automated dispatch technology inherently increase the supply of workers, because they make it possible for even part-time workers to be successful at finding passengers and navigating even to out-of-the-way locations. There was formerly an “experience premium,” whereby experienced drivers knew the best way to reach a given destination or to avoid traffic. Now, anyone equipped with a smartphone and the right applications has that same ability. “The Knowledge,” the test required to become a London taxi driver, is famously one of the most difficult exams in the world. The Knowledge is no longer required; it has been outsourced to an app. An Uber or Lyft driver is thus an “augmented worker.”

- The reliability and ease of use of Uber and Lyft makes it much easier for passengers to get pickups in locations where taxis do not normally go, and at times when taxis are unavailable. This predictability of supply not only satisfies unmet demand, but leads to increased demand. People are now more likely to travel more widely around the city, whereas before they might have avoided trips where transportation was hard to find. There are other ancillary benefits, such as the ability for passengers to be picked up regardless of race, and for some previously unemployable populations (such as the deaf) to serve as drivers.

- Unlike taxis, which must be on the road full time to earn enough to cover the driver’s daily rental fee, the “pay as you go” model allows many more drivers to work part time, leading to an ebb and flow of supply that more naturally matches demand. Drivers provide their own vehicles, earning additional income from a resource they have already paid for that is often idle, or allowing them to help pay for a resource which they are then able to use in other parts of their life. (Obviously, they incur additional costs as well, but these costs are generally less than the costs of daily taxi rental. There are many other labor issues as well; these will be the subject of a later essay.)

- Unlike taxis, which create an artificial scarcity by issuing a limited number of medallions, Uber uses market mechanisms to find the optimum number of drivers, with an algorithm that raises prices if there are not enough drivers on the road in a particular location or at a particular time. While customers initially complained, this is almost a textbook definition of a Supply and Demand Graph, which uses market forces to balance the competing desires of buyers and sellers.

- More drivers means better availability for customers, and shorter wait times. Uber is betting that this will, in turn, lead to changes in consumer behavior, as more predictable access to low-cost transit causes more people to leave their personal car at home and use the service more. This, in turn, will allow the service to lower prices even further, which will increase demand in a virtuous circle. This is the same pattern that has driven American business since the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (A&P) pioneered the model in the early part of the 20th century.

- There are concerns about whether lowering prices affects driver income. So far, there are many accusations from critics but no hard evidence that this is the case. Uber argues that greater demand will actually increase driver income. In any case, Uber is now putting its money where its mouth is and guaranteeing driver income when it lowers fares.

- There are also concerns about the impact of Uber and Lyft on urban congestion. But the data on the subject is equivocal. And while the current algorithm is optimized to create shorter wait times, there is no reason it couldn’t take into account other factors that improve customer satisfaction and lower cost, such as the impact of too many drivers on congestion and wait time. Algorithmic dispatch and routing is in its early stages; to think otherwise is to believe that the evolution of Google search ended in 1998 with the invention of PageRank.

- A crowdsourced rating system is far from perfect, but it delivers visibly better and more consistent results than whatever management processes were performed by traditional taxi companies.

- There is no absolute requirement that drivers be individuals, and the supplier networks to these platforms will continue to evolve.

The franchise of one

In my initial post, The WTF Economy, I wrote:

WTF?! Without owning a single room, Airbnb has more rooms on offer than some of the largest hotel groups in the world. Airbnb has 800 employees, while Hilton has 152,000.

It would have lacked the immediate punch, but I could also have written:

WTF?! Without owning a single restaurant, Subway has more fast food restaurants than McDonald’s. Subway has 900 employees. McDonalds has 420,000.

The reason: Subway owns no restaurants, while McDonalds owns 20% of its restaurants, with the remaining 80% franchised. (Employment across both owned and franchised restaurants at McDonalds is more than 1.9 million.)

In many ways, Uber and Airbnb represent a 21st century update of the franchising model. In franchising, the parent company brands and markets the product, sets standards for producing it, and charges a licensing fee and receives a percentage of revenue from each of its franchisees.

The difference is that technology radically lowers the barriers to being a franchisee. In many ways, you can call the modern trend “the franchise of one.” The smallest unit of franchising in the past was a small business, with all the overhead that implies: real estate, equipment, uniforms, employees (including managers), and so on. Today, the franchise can be a single individual, and that individual can work only part time, so it’s really “the franchise of one or even less!”

Branding and advertising are much less necessary because the app itself becomes a customer habit that delivers business. There are little or no capital requirements, workers can schedule their own time, and turn their own under-utilized personal assets (a car, a house, or other equipment) into business assets. In her book Peers Inc, Robin Chase refers to this as “excess capacity.”

This is exactly the dynamic that Kilpi references when he describes how the radically lower transaction costs of networks give them advantages over traditional firms.

Though the details of the taxi industry differ from the hotel industry, the same dynamic applies to another great success story of the on-demand economy: Airbnb. Like Uber and Lyft, Airbnb uses technology to make excess capacity available in locations that were otherwise extremely poorly served. Even in great cities, hotels are available only in some neighborhoods, and completely unavailable in others. By contrast, Airbnbs can be found anywhere that there is demand.

A small personal anecdote: I recently got married in Fort Tryon Park in New York City, near the Cloisters. The nearest hotel is 1.5 miles away, and the closest “nice” hotel is 3.8 miles, yet my fiance and I were able to walk to our wedding site from a beautiful, comfortable Airbnb facing the park and just five minutes away. Many of our guests stayed locally as well.

As with Uber and Lyft, we see that the granular nature of supply (the franchise of one, or even less than one) makes it easy for more natural market mechanisms to come into play. People can offer a resource that they already own, testing the market to see if there is demand and at what price. If they are satisfied with the transaction, they can continue to offer that resource. More supply will come on stream to match demand in highly desirable locations.

There are some interesting lessons, though, about the evolution of the supply network. While Airbnb began as a network of properties offered solely by individuals, already 40% of Airbnb properties are now offered by hosts who own more than one property. There are also anecdotal reports that small companies owning multiple cars are starting to be part of the Uber network.

From decentralization to recentralization

The evolution of Airbnb’s network echoes the evolution of the World Wide Web and the media platform businesses that grew up on it, such as Yahoo, Google, YouTube, and Facebook.

The World Wide Web began as a peer-to-peer network of individuals who were both providing and consuming content. Yet 25 years on, the World Wide Web is dominated by the media presence of large companies, though there is still plenty of room for individuals, mid-sized companies, and aggregators of smaller companies and individuals. While the platform itself began in decentralized fashion, its growth in complexity led to increasing centralization of power. Everyone started out with an equal chance at visibility, but over time, mechanisms were invented to navigate the complexity: first directories, then search engines.

Eventually, there grew up a rich ecosystem of intermediaries, including, at the top of the food chain, first Yahoo! then Google and their various competitors, but also content aggregators of various sizes and types, such as the Huffington Post and Buzzfeed ,as well as various companies, from Search Engine Optimizers to advertising firms like DoubleClick and Aquantive, and content delivery firms like Akamai and Fastly, who help other firms optimize their performance in the marketplace.

Later media networks such as YouTube, Facebook, and the Apple App Store bypassed this evolution and began as centralized portals, but even there, you see some of the same elements. In each case, the marketplace was at first supplied by small individual contributors, but eventually, larger players — companies, brands, and superstars — come to dominate.

In addition, the central player begins by feeding its network of suppliers, but eventually begins to compete with it. In its early years, Google provided no content of its own, simply sending customers off to the best independent websites. But over time, more and more types of content are offered directly by Google. Amazon began simply as a marketplace for publishers; eventually, they became a publisher. Over time, as networks reach monopoly or near-monopoly status, they must wrestle with the issue of how to create more value than they capture — how much value to take out of the ecosystem, versus how much they must leave for other players in order for the marketplace to continue to thrive.

I believe we will see some of these same dynamics play out in the new networked platforms for physical world services, such as Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb. Successful individuals build small companies, and some of the small companies turn into big ones. Eventually, existing companies join the platform. By this logic, I expect to see large hotel chains offering rooms on Airbnb, and existing taxi companies affiliating with Uber and Lyft. To optimize their success, these platforms will need to make it possible for many kinds of participants in the marketplace to succeed.

Key lessons

Here are some key lessons for companies wanting to emulate the success of Internet marketplaces like Amazon, Google, Uber, and Airbnb:

- Lower transaction costs are what drive the evolution of the market from traditional firms to large networks. Therefore, focus relentlessly on lowering barriers to entry for both suppliers (workers) and customers.

- Networks aggregate customers very effectively, reducing the number of other companies that sell directly to those customers, thus leading to industry consolidation. As Jeff Bezos famously said, “[Their] margin is my opportunity.” Look, therefore, for fragmented markets where technology allows you to create new economies of scale.

- The lower costs of doing business at scale make it possible to offer products to the market at lower prices, increasing demand. Be sure to pass savings on to the customer. Given sufficient investment, you can scale more quickly by passing on the savings even before you get to scale. Jeff Bezos was able to convince the market of this proposition, enduring years of losses or very low margins, even as a public company, in order to reach massive scale. Uber appears to be following the same playbook.

- That being said, use market mechanisms and data to innovate on pricing. Google famously revolutionized advertising by creating an auction system that favors the most effective advertisements rather than the highest bidder. I expect similar business model innovations in the on-demand space, as the power of big data makes it possible to make a real-time market in various kinds of services.

- Networked platforms serve customers who were previously hard to reach, thus increasing the total number of customers. Therefore, don’t just skim the cream. Build mechanisms to extend your network to underserved populations, creating new markets. Many of the second-tier on-demand companies are doomed to fail because they only target small populations of affluent consumers, rather than finding a path in which the virtuous circle of scale and lower cost eventually allows them to serve a much broader market.

- Networks aggregate suppliers very effectively, increasing both the total number of available products and the total number of suppliers. Suppliers range from single individuals offering a single product to huge firms, with many levels of smaller firms, and also intermediaries who aggregate those smaller firms. Therefore, build in mechanisms that will support suppliers of all sizes. (Note to policy makers considering the employment status of on-demand workers: suppliers to on-demand platforms will eventually include companies of many sizes, not just individuals.)

- When you open the market to an unlimited number of suppliers, you must invest in reputation systems, search algorithms, and other mechanisms that help bring the best to the top. Simple, easily gamed reputation systems are table stakes; over time, more sophisticated curation will be necessary.

- Internet-era networks don’t just seek to eliminate workers; they seek to augment them. Invest in software that empowers your workers, allowing them to multiply their effectiveness and to create magical new user experiences for customers. We will talk more about augmented workers in a future installment of the WTF Economy series of essays on Medium.

Editor’s note: this post was first published on Medium; it is republished here with permission.