The Spellbinding History of Cheese and Witchcraft (original) (raw)

This article about the magical properties of cheese is republished here with permission from The Conversation. This content is shared here because the topic may interest Snopes readers; it does not, however, represent the work of Snopes fact-checkers or editors.

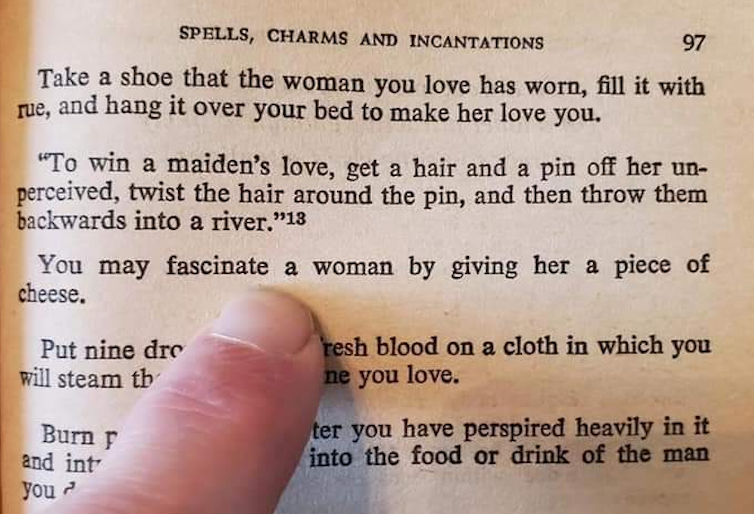

As I was scrolling through Twitter recently, a viral tweet caught my attention. It was an image from a book of spells claiming that: “You may fascinate a woman by giving her a piece of cheese.” The spell comes from Kathryn Paulsen’s 1971 book, The Complete Book of Magic and Witchcraft – and, while proffering a lump of cheddar may seem like an unusual way of attracting a possible mate, Paulsen’s book draws on a long history of magic. It’s a history that has quite a lot of cheese in it.

It’s not entirely clear why cheese is seen to have magical properties. It might be to do with the fact it’s made from milk, a powerful substance in itself, with the ability to give life and strength to the young. It might also be because the process by which cheese is made is a little bit magical. The 12th-century mystic, Hildegard von Bingen, compared cheese making to the miracle of life in the way that it forms curds (or solid matter) from something insubstantial.

In the early modern period (roughly 1450-1750) the creation of the universe was also thought of by some in terms of cheesemaking: “all was chaos, that is, earth, air, water, and fire were mixed together; and out of that bulk a mass formed – just as cheese is made out of milk – and worms appeared in it, and these were the angels.” The connection with life and the mysterious way that cheese is made, therefore, puts it in a good position to claim magical properties.

Cheese magic stretches back long before Hildegard and the medieval period. The 2nd-century diviner, Artemidorus, mentions “tyromancy” – cheese divination – as a method of discovering the future in his treatise Oneirocritica. Ironically, given our later association of cheese with vivid dreams, Artemidorus claims that cheese fortune-telling is among the most unreliable.

This didn’t stop later generations from interpreting cheese dreams, though. The Interpretation of Dreams, a 17th-century English manual, advised that: “[to dream of] cakes without cheese is good; those which have both signifie deceit and treason by a Welshman.”

Unusual advice for the lovelorn.

Kathryn Paulsen: The Complete Book of Magic and Witchcraft

One of the most common uses for magic cheese in the medieval and early modern periods was to identify thieves and murderers. The method could be quite simple. First bless cheese with a prayer. For example, you might say:

May his mouth be cursed and full of bitterness, under his tongue pain and labour. If he is guilty, he will eat in the name of the devil. If he is not guilty, he will eat in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Then feed a small piece to each of your suspects. The culprit will be unable to swallow their piece of cheese, thus admitting their guilt.

Mischievous magic

Even if you’re not a thief, you should be wary around cheese when there’s a witch in the room. In The Odyssey, the sorceress Circe turns Odysseus’ companions into animals by feeding them a magic potion mixed into a drink made of cheese, barley meal, honey and wine. The fourth century Christian theologian, St Augustine of Hippo, agreed that such things might be possible, though unlikely.

William of Malmesbury seemed convinced that enchanted cheese was a genuine risk, though, and in his 12th-century writings William explained that female Italian innkeepers were especially prone to using enchanted cheese to turn their customers into beasts of burden.

Making Circe angry meant it was ‘hard cheese’ for the companions of Odysseus.

Creator:Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione/Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Malevolent witches were also thought to meddle with milk and cheese: in fact, spoiling milk was one of the most common curses associated with witches in early modern Europe. Around 1650, the dairymaid Isabel Maine was convinced her milk was cursed, as it wouldn’t turn into cheese. Only after a service magician named Margaret Stothard performed a counter-curse would the milk curdle properly. Margaret advised Isabel to carry a stick of rowan wood when she milked the cows in future, to protect the milk from “evil eyes”.

On a more playful side, though still a serious annoyance for their neighbours, witches were also thought to magically steal milk directly from cows’ udders. A 14th century morality manual tells a story about a woman with an enchanted leather bag. On her command, the bag would leap up and run to her neighbours’ cattle herd, where it would secretly steal milk and bring it back to her.

Charming cheese

The idea that cheese is seductive also has a long history. Writing in the 13th century, the moralist and theologian Odo of Cheriton used the alluring smell of grilled cheese to explain adultery:

Cheese is toasted and placed in a trap; when the rat smells it, it enters the trap, seizes the cheese, and is caught by the trap. So it is with all sin. Cheese is toasted when a woman is dressed up and adorned so that she entices and catches the foolish rats: take a woman in adultery and the Devil will catch you.

The link between cheese and love magic doesn’t stop at seduction, though. In 14th-century Germany, biting a piece of bread and cheese and throwing it over your shoulder was meant to ensure fertility in a relationship. Cheese could also cure male impotence: if a pesky witch had cursed a man’s genitals, a medieval Italian cure was for the man’s wife to bore a hole in cheese, and feed him the resulting pieces.

Given Europeans’ longstanding attraction to cheese, perhaps it’s no wonder that Kathryn Paulsen’s spell is so short and why it needed no further elaboration.

Tabitha Stanmore, Honorary Research Fellow, Early Modern Studies, Department of History, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.