Callisto: Everything you need to know about Jupiter's second-largest moon (original) (raw)

Photograph of the Callisto moon captured from NASA Galileo spacecraft. (Image credit: NASA/JPL/DLR)

Callisto is Jupiter's second-largest moon and the outermost of the Galilean satellites.

It has an ancient, cratered surface, indicating that geological processes could be dead. However, it may also hold an underground ocean. It's unclear if the ocean could sustain because the surface is so old.

Jupiter's moon Callisto has been the subject of several flybys, including the long-running Galileo mission at Jupiter in the 1990s and 2000s. The JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer) mission will focus on three icy Jupiter moons, including Callisto, to get more information about its environment. JUICE is expected to arrive in 2030.

Related: Jupiter missions: Past, present and future

Several icy moons of the solar system have been a focus of exploration in recent years because of their potential for holding life. The Cassini spacecraft, which orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017, uncovered extensive evidence of geysers on its moon, Enceladus. Other icy moons include Triton (at Neptune, imaged by Voyager 2) and Europa (another icy moon of Jupiter.) In general, these moons maintain liquid oceans because of the gravitational tug from their large giant planets.

Who discovered Callisto and when?

Jupiter's four largest moons — Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto — are also known as the Galilean moons, named after Galileo Galilei, who discovered them in 1610. All four are bigger than Pluto, and Ganymede is the largest moon in the solar system, even bigger than Mercury.

Photos: The Galilean moons of Jupiter

When Galileo turned his telescope to Jupiter on Jan. 7, 1610, what he saw surprised everybody. The planet was not alone; it had four moons circling it. At the time, it was believed that the Earth was the only planet with a moon. For two centuries Jupiter's moons were (as a group) named after the Medicis, a powerful Italian political family, according to NASA. Individually they were called Jupiter I, II, III and IV, with "IV" referring to what we now call Callisto.

The discovery had not only astronomical, but also religious implications. At the time, the Catholic Church supported the idea that everything orbited the Earth, an idea put forth in ancient times by Aristotle and Ptolemy. Galileo's observations of Jupiter's moons — as well as noticing that Venus went through "phases" similar to our own moon — gave compelling evidence that not everything revolved around the Earth.

As telescopic observations improved, however, a new view of the universe emerged. The moons and the planets were not unchanging and perfect; for example, mountains seen on the moon showed that geological processes happened elsewhere. Also, all planets revolved around the sun. Over time, moons around other planets were discovered — and additional moons were found around Jupiter. The Medici moons were renamed Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto to avoid confusion in the mid-1800s.

Callisto key facts

Age: Callisto is about 4.5 billion years old, about the same age as Jupiter. It is the most heavily cratered object in the solar system, according to NASA. There is hardly any geologic activity on its surface. The surface has not changed much since initial impacts molded its surface 4 billion years ago.

Distance from Jupiter: It is the outermost of the Galilean moons. Callisto orbits Jupiter at a distance of about 1,168,000 miles (1,880,000 kilometers). It takes the moon about seven Earth-days to make one complete orbit of the planet. It also experiences fewer tidal influences than the other Galilean moons because it orbits beyond Jupiter's main radiation belt. Callisto is tidally locked, so the same side always faces Jupiter.

Size: At 3,000 miles (4,800 km) in diameter, Callisto is roughly the same size as Mercury. It is the third largest moon in the solar system, after Ganymede and Titan. (Earth's moon is fifth largest, following Io.)

Temperature: The mean surface temperature of Callisto is minus 218.47 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 139.2 Celsius).

Callisto FAQs answered by an expert

We asked Adeene Denton, postdoctoral researcher at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, a few frequently asked questions about Callisto.

Adeene Denton is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory studying how giant impacts can reveal the interior structure and geologic evolution of icy satellites and ocean worlds.

Is Callisto habitable?

Literally no one knows the answer to this, because we don't really agree on what the interior of Callisto might look like. There's a whole argument about whether Callisto is even differentiated — we know that it's made of ice and rock, and theoretically the rock should settle below the ice in the kind of stratification we know happens on other worlds. Whether and how that happens in the interior of Callisto could determine whether and when an ocean might form. If Callisto has an ocean, which would presumably be the most habitable location, it would be buried beneath a thick ice shell (much thicker than Europa's). Could life evolve and thrive under those conditions? Maybe! I won't rule it out.

Where is Callisto located?

Callisto is the most distant of the Galilean satellites (the others being Io, Europa, Ganymede), and thus is the farthest away from Jupiter. For those counting, it's ~26 Jupiter radii away from its planet, which is notable primarily because it's much farther away than its next closest neighbor, Ganymede (~15 Jupiter radii away).

What's an interesting fact about Callisto?

Despite being considered the "least interesting" of the Galilean satellites (rude! and untrue!) Callisto has some of the coolest impact craters in the solar system! Callisto's impact basin Valhalla is the largest multi-ring basin in the solar system, with a massive number of concentric rings that spread out from the center like a massive ripple. As an impact scientist, I think Valhalla, and its smaller compatriot Asgard, are incredibly beautiful in addition to telling us something about the interior — the large number of rings is thought to arise from a contrast between the brittle ice shell at the surface and a more viscous material beneath it. There's still a lot we don't know about Callisto, and it's exciting to think about the possibilities.

Observing Callisto

While telescopes improved substantially by the Space Age of the 1960s, still little was known about Callisto, according to the 2004 book "Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere" (Cambridge, 2007). From what astronomers could tell, the surface looked relatively featureless compared with Io and Ganymede. Callisto also had low reflectivity (albedo) and was known to have a low density, but astronomers saw no evidence of water emissions. This led them to conclude that Callisto had a rocky surface.

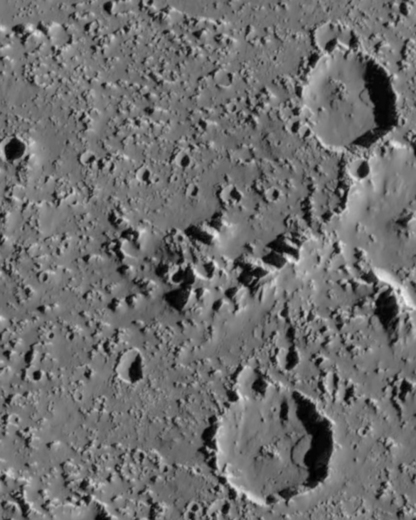

Galileo spacecraft images of the surface of Jupiter's moon Callisto have revealed large landslide deposits within two large impact craters. The two landslides are about 3 to 3.5 km in length. (Image credit: Lunar and Planetary Institute/Arizona State University)

Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 each flew by Jupiter and its moons in the early 1970s, but these missions didn't give much new information on Callisto beyond what Earth-based telescopes showed. It was the Voyager missions of the late 1970s that really showed us a different picture of the moon. Callisto's density and temperature were refined, and images of the surface showed features as small as 1 kilometer per pixel — in other words, a resolution small enough to spot impact craters. In fact, Callisto was very heavily cratered compared with the other moons, the authors wrote. "Some dismissed Callisto as the most boring object of its size in the solar system," they added.

More close-up observations required a wait until 1996 when the Galileo spacecraft commenced the first of 12 flybys of the moon. Galileo's repeated flybys and higher resolution revealed much more information about Callisto than before. More of the surface was mapped, a thin carbon dioxide atmosphere was discovered, and evidence of a subsurface ocean was uncovered.

Arguments for an ocean came from two pieces of evidence, according to NASA. First, scientists saw regular fluctuations of Callisto's magnetic field as the moon circled Jupiter, which implied there were electrical currents within the moon stimulated by the planet's magnetic field. That current had to conduct from somewhere, which led to the second piece: due to the rocky surface and thin atmosphere, a likely explanation would be a salty ocean under the moon's surface.

In 2018, examinations of archival images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2007 showed Callisto's effect on auroral bursts in Jupiter's atmosphere. Jupiter generates auroras on its own, but some of the phenomena come through interactions with its four largest moons: Europa, Io, Ganymede and Callisto. The signatures of the other moons were previously spotted in Jupiter's atmosphere, but this new research represented the first time that Callisto's effect was found.

Callisto and the other Galilean moons may have formed with the assistance of Saturn. A computer model released in 2018 suggested that as Saturn's core grew, its gravitational influence moved planetesimals (baby planets) toward the inner solar system. This process might have provided enough stuff to form the four Galilean moons.

Additional resources

Explore Callisto in more detail with these resources from the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). See Callisto and Io travel parade across Jupiter in these stunning Hubble Space Telescope images. Take a look at what ESA's JUICE mission might discover about the Galilean moons: Ganymede, Europa and Callisto with these resources from the European Space Agency (ESA).

Bibliography

Bagenal, F., Dowling, T. E., & McKinnon, W. B. (2007). Jupiter: The planet, satellites and magnetosphere. Cambridge University Press.

NASA. (n.d.). Callisto In depth. NASA. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/callisto/in-depth/

NASA. (n.d.). Callisto makes a big splash. NASA. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/1998/ast22oct98_2/

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace