Kathryn Sullivan: Spacewalker and Earth Explorer (original) (raw)

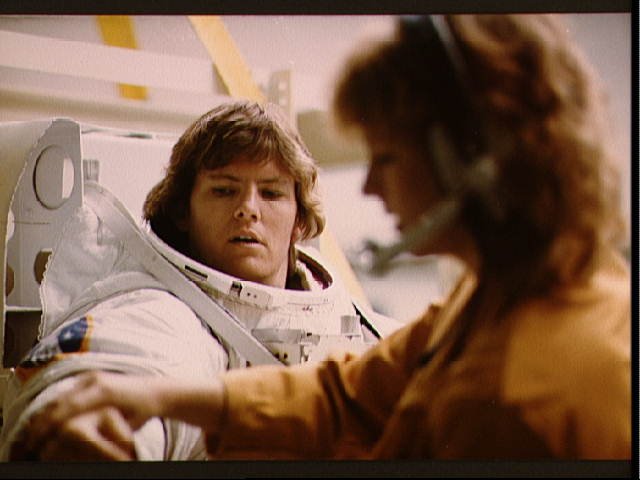

NASA astronaut Kathryn Sullivan undergoes spacewalk training for the STS-41-G mission in 1984. (Image credit: NASA)

Few know the globe's nooks and crannies more intimately than Kathryn Sullivan — intrepid explorer of the sky and the sea. As an astronaut, she stepped out of the space shuttle's airlock to become the first American woman to float freely through space. She was also instrumental in the planning and launch of the Hubble Space Telescope.

What motivated Sullivan wasn't a hunger for the final frontier, but a passion for Earth. After 15 years and three trips to space, she left NASA and returned to her academic roots as an oceanographer and Earth scientist. She became the chief scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), oversaw science education at the Center of Science and Industry in Ohio and eventually served as the administrator of NOAA, where she oversaw initiatives related to Earth observation and weather forecasting.

"My real roots are a fascination with the planet and how it works, and a desire to explore every facet of that I can," she said during a lecture at the Symphony Space performing arts center in New York City on Dec. 3, 2019.

From linguist to scientist

Sullivan was born in New Jersey but grew up in Woodland Hills, California, where her enthusiasm for adventure drove her toward linguistics. "When I was in high school," she said, "I believed my path would be best set by learning a lot of languages, and somehow that would turn into a life where people bought me airline tickets to go explore all of these places that I wanted to explore."

But as a freshman at the University of California, Santa Cruz, general education requirements forced Sullivan to broaden her horizons with science classes. Despite her protests that she wanted to study languages and arts exclusively, she ended up taking earth science and oceanography. "I thought it was a terrible idea," she said, but "I lost all the arguments."

Those classes introduced her to an unexpected side of science — one where researchers spent much of their time not in harshly lit laboratories, but out in the field getting their hands dirty. She found that research, more than languages, could help her achieve the lifestyle she desired. "People were always buying [my professors] plane tickets to fly off to interesting places," Sullivan said.

She changed her major to earth sciences at the end of her freshman year, then went on to earn a Ph.D. in geology from Dalhousie University in Canada and never looked back.

Kathryn Sullivan contemplates the Earth from the space shuttle. (Image credit: NASA)

From the seas to the skies

During her doctoral studies, Sullivan joined multiple oceanographic expeditions to study the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and other deep-sea features. And by the time she received her degree, she had secured a fellowship offer to continue her exploration of the Atlantic in deep submersibles.

But an entirely new type of research vessel also called to her. By 1978, NASA was evolving from a quasi-militaristic organization determined to win the space race into the more civilian-friendly, scientific institution it is today. Whereas previous members of the astronaut corps had come exclusively from the ranks of military test pilots, the agency had just opened its recruiting pipeline to include civilian researchers who would be needed to work on the upcoming space shuttle.

Immediately after graduate school, Sullivan interviewed to become an astronaut; it was her first serious job interview, she recalled. And, at age 26, her first full-time job was as an astronaut.

In the winter of 1978, Sullivan joined NASA's eighth class of astronauts, nicknamed the "Thirty-Five New Guys" (TFNG). Because astronaut recruitment was no longer restricted to Air Force pilots, the new group represented NASA's first step toward a more diverse astronaut corps, including six women, three African American men and one Asian American man — all firsts for the elite cadre.

"By the end of our first day, right after we'd been introduced to the public, it became clear to all of us that the simple way to describe our group was 10 interesting people and 25 standard white guys," Sullivan joked.

But if any at the agency disapproved of its new recruits, they kept those thoughts to themselves. "All six of us [women] would say we got a remarkably clear runway," Sullivan said. "No one had ever seen an astronaut that looked like me, but they had always treated astronauts [with respect]."

NASA astronauts (L to R) Shannon W. Lucid, Margaret Rhea Seddon, Kathryn D. Sullivan, Judith A. Resnik, Anna L. Fisher and Sally K. Ride. These six women were the first official female astronaut candidates. (Image credit: NASA)

For the next six years, Sullivan trained, studied and supported other missions until she reached the front of the line. Sally Ride had become the first American woman in space the year before, and in early 1984, Sullivan learned that she and Ride were scheduled for an October mission during which Sullivan was scheduled to perform a spacewalk.

Colleagues excitedly congratulated Sullivan and Ride on the privileges of being the first woman spacewalker, and first woman to visit space twice, respectively. Both women, however, knew that a lot could change in 10 months. "Sally and I looked at each other and said, 'these people have not been paying attention to history,'" Sullivan said.

The space race was over, but NASA's rivalry with the Soviet space program lived on. After the public announcement of Sullivan and Ride's historic flight, Soviet mission planners had plenty of time to arrange for cosmonaut Svetlana Savitskaya to fly her second mission and pull off a spacewalk while she was up there, beating Sullivan and Ride by three months.

Being the first American woman to walk in space was more than enough for Sullivan, however. In October 1984, she flew on the space shuttle for an eight-day mission and "snuck outside on the second to last day for several hours," she recalled. Sullivan tested out new technology for refueling an orbiting satellite to extend its life span. While the demonstration was successful, the technology has yet to be put to use.

Astronaut Kathryn Sullivan poses for a picture with her space suit during a 1995 shuttle mission. Sullivan was the first American woman to go on a spacewalk. (Image credit: NASA)

Sullivan's work with Hubble

Sullivan went on to spend more than 530 hours in space over three missions, but she views her work with the Hubble Space Telescope as one of her most lasting contributions.

In 1985, a NASA supervisor told Sullivan that the large space telescope, custom designed to fit snugly into the space shuttle's cargo bay, was expected to be completely serviceable and upgradeable. It would be up to her and fellow astronaut Bruce McCandless II to oversee the development of tools and procedures needed to ensure that astronauts would be able to keep the complex machine running smoothly. The task of readying the instrument to be serviced under such restrictive conditions, Sullivan recalled, was a big one. "Imagine putting on two full-body snowmobile suites, bolting a bucket on your head and wearing heavy gloves under mittens," she said. "Now go change the spark plugs on your car."

But after five years of research and countless hours of weightless practice in NASA's Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory (a giant pool in Houston, Texas), a repairable Hubble was ready for launch in 1990. The deployment went smoothly — although Sullivan didn't get to watch it happen because she was stuck in a windowless airlock, standing by in case an emergency spacewalk became necessary.

Sullivan, who recently published a book detailing her experiences with the space telescope called "Handprints on Hubble" (MIT Press, 2019), marveled at how the twists and turns of the instrument's journey to space mirrored many parts of her own career. Since the Hubble project began five years before Sullivan’s birth, it’s almost like “he's my older brother," she said.

From the skies to the planet

In 1993, after 15 years as one of the "Thirty-Five New Guys," Sullivan accepted a nomination from President Bill Clinton to serve as the chief scientist at NOAA, a sister agency to NASA, focusing on Earth's oceans and atmosphere. In this role, she supervised initiatives related to ocean biodiversity and climate change. She went on from there to become the president and CEO of the Center of Science and Industry — a science museum in Columbus, Ohio — and the director of the Battelle Center for Mathematics and Science Education Policy at The Ohio State University.

She returned to NOAA in 2011, nominated by former President Barack Obama and unanimously confirmed by the U.S. Senate to serve as the agency's deputy administrator. Three years later, she became NOAA's 10th administrator, and led the organization's efforts to coordinate observations from space, land and sea to provide the best weather and climate forecasts possible. For Sullivan, this work served as a natural culmination of a life spent exploring the Earth. NOAA's niche, she said, is "to keep the pulse of the planet, to measure and monitor the things that can help us make those better decisions; and then broker, package and transmit the information to us, as a weather forecast, or to heads of state or to fishermen."

Even her time off the planet was driven by a desire to better understand it. "My deepest personal motivation for even filling out the astronaut application," she said, "was that if by some miracle I beat the odds and got selected, I'd get to see the Earth with my own eyes."

It's easy to imagine that seeing Earth from space would enhance the grandeur of the universe compared to the smallness of our home. But when Sullivan looked down at Earth's continents, oceans and clouds, she saw a complicated place shaped by both natural forces and the various enterprises of humanity. "Carl Sagan writes about the 'Pale Blue Dot' — not my experience," she said. "I did [see] the vivid blue beach ball."

Additional resources:

- Read about Sullivan's many accomplishments in her NASA astronaut profile.

- Listen to Sullivan describe her time in space, and how the space program helps us better understand Earth, in this lecture at the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.

- Read astronaut John Glenn's thoughts honoring Sullivan's selection as one of Time's most influential people in 2014.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Charlie Wood is a freelance journalist covering physical sciences both on and off this pale blue dot. He contributes to Space.com and LiveScience, as well as Popular Science, Scientific American, Quanta Magazine, and others. These days he writes from New York but in previous lives he taught physics in Mozambique and science English in Japan. Find him on Twitter @walkingthedot.