Lenin’s view of the July 1912 Zurich strike (original) (raw)

The Zurich general strike of July 12, 1912, is depicted in a postcard belonging to the Karl Stehle collection in Munich Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv

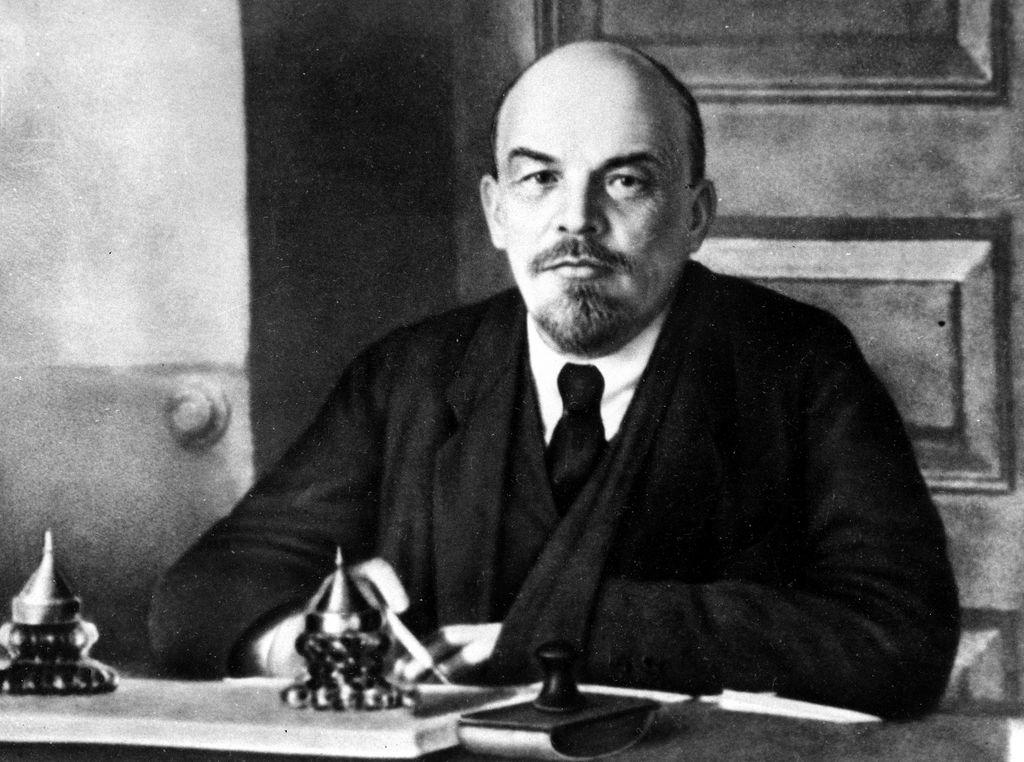

Exactly 100 years ago, one of the most important general strikes in Swiss history took place in Zurich. Russian exile Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov – Lenin – provided his impressions of the July 12, 1912, strike in the daily Russian newspaper Pravda.

This content was published on July 12, 2012 - 18:26

6 minutes

Jeannie Wurz, swissinfo.ch

His three-page commentary, translated into English in Lenin Collected Works and available through the Marxists Internet Archive, provides an eyewitness account of Swiss society at the time.

The July 12 strike was important because it was the biggest general strike up to that time, and not only a strike of one profession or one industry, Bernard Degen of Basel University’s history department told swissinfo.ch.

The strike “was well organised. The strikers were very disciplined. They began at the time they were called to strike and they ended at the time they decided. And there were no problems,” Degen said.

First strike

Switzerland in the early 1900s was undergoing an industrial boom, particularly in the machine and building industries. There was heavy dependence on foreign labour, with close to 17 per cent of workers in 1910 being foreigners, the majority Germans and Italians.

But whereas the employers were profiting from the boom, the workers were not.

In March and April 1912, unhappy painters and fitters staged strikes in Zurich, demanding a reduction in working hours of 30 minutes a day. Their employers reacted by creating blacklists, deporting foreign strikers and importing strike-breakers from Germany.

Lenin described the strike-breakers as a “riff-raff gang of convicts (lumpenproletarians) with pistols” who “filled the taverns in the workers’ district and there engaged in unheard-of hooliganism”.

After a strike-breaker shot and killed a striker, the workers resolved to protest and organised a one-day strike for July 12, 1912.

“Philistine spirit”

The general strike, one of nine that took place in Switzerland between 1902 and 1912, began at 9am with a protest on Zurich’s Rotwandwiese. As many as 23,000 workers representing a variety of nationalities took part.

“The drowsy, philistine spirit which often in the past pervaded some of the Swiss workers’ associations is disappearing to give way to the fighting mood of a class-conscious and organised proletariat that is aware of its strength,” Lenin wrote.

Although he lived in Switzerland between 1903 and 1905, in 1908, and from 1914 to 1917, Lenin apparently was not living in Switzerland at the time of the 1912 strike. Based on his descriptions, however, he may have been present on the day.

“Thirty-thousand leaflets in German and Italian were circulated in the early morning,” he reported. “Some 2,000 strikers occupied the tram depots. Everything stopped. Life in the city came to a standstill. Friday is a market day in Zurich, but the city seemed dead.”

Government reaction

Although the strike was peaceful, reaction from employers and authorities was harsh.

“The government and the capitalists, who had hoped to provoke the workers to violence, saw their failure and are now beside themselves with rage,” Lenin commented.

Employers set a two-day lockout for strikers. The Zurich cantonal government mustered three Fusilier battalions and a cavalry squadron – 3,000 men in total – to keep order.

The authorities forbade congregation and demonstrations, and announced new measures against striking city government employees and the expulsion of foreign strikers from Switzerland.

“It’s strange that Lenin doesn’t mention the army”, Josef Lang, a historian and vice-president of the centre-left Green Party, told swissinfo.ch.

“Lenin could have radicalised his text with the element of the army, but he didn’t realise.”

While Lenin mentioned that the police occupied the People’s House, a union headquarters, Lang said “it was the army which surrounded the People’s House. It was an intervention of the army”.

Importance

In spite of the negative reaction from the government, the strike was viewed as a success.

“The idea was to put pressure on the government, and this happened for the first time,” said Degen, who specialises in 20th-century Swiss history.

“Officially, the government never makes concessions. But in fact, people learned that the government would be more careful with them.”

Up until the 1930s, Switzerland was a country with many strikes in comparison to other countries, according to Lang. Today, although there are many unions and the unions have many members, they don’t often strike. Lang said there were three reasons for this.

First, in 1937 the leaders of the unions and the leaders of the capitalists crafted an agreement.

“When there is a contract between the unions and the employers, there is no right to strike,” he said. “It’s not forbidden by law; it’s forbidden by agreement. We call it the Agreement of Peace.”

Second, today’s workers can make their concerns known through direct democracy.

“In other countries, the only possibility is to strike. In Switzerland you can make people’s initiatives. Or you can make referendums against working laws for example.”

Third, because Swiss cantonal governments are elected by the people, there have been left-wing politicians in the cantonal government for more than 100 years.

Influence

Degen didn’t believe the strike had any influence on Lenin’s later activities as the leader of the Bolshevik revolution.

The Zurich strike “was not a strike in the sense of Lenin”, he said.

“Lenin thought more about the strikes in Russia in 1905, which were much stronger, longer. The strike in Switzerland was very well organised. I think he would rather think that was a bureaucratic strike.”

Lenin spent six-and-a-half years in total in Switzerland.

Between 1903 and 1905 and in 1908 he lived in Geneva, from 1914 to 1915 he was resident in Bern and from 1916 to 1917 he lived in Zurich.

In September 1915 he attended the first conference of European Socialists opposed to the war at Zimmerwald in Bern. Delegates heard Lenin call for the transformation of the “imperialist” war into a civil war. The next year a follow-up conference was held in Kiental.

During his time in Zurich Lenin tried to split the Social Democratic party to found a movement which would bring about a popular revolution in Switzerland and elsewhere.

Read more

More

Lenin and the Swiss non-revolution

This content was published on May 19, 2006 Lenin, the father of the Russian revolution, worked on his theories for a popular uprising while living in Switzerland.

Read more: Lenin and the Swiss non-revolution

More

Russia and Switzerland

This content was published on Sep 8, 2009 War and peace, work and leisure, rich and poor, expected and unexpected: regular contacts between Switzerland and Russia go back to the 18th century.