Bedlam - The Comics Journal (original) (raw)

I am going to write briefly about some things I read recently, as I've been reminded that I'm supposed to be writing about comics in addition to editing articles and shouting at myself in the mirror like Willem Dafoe in Spider-Man (2002).

* * *

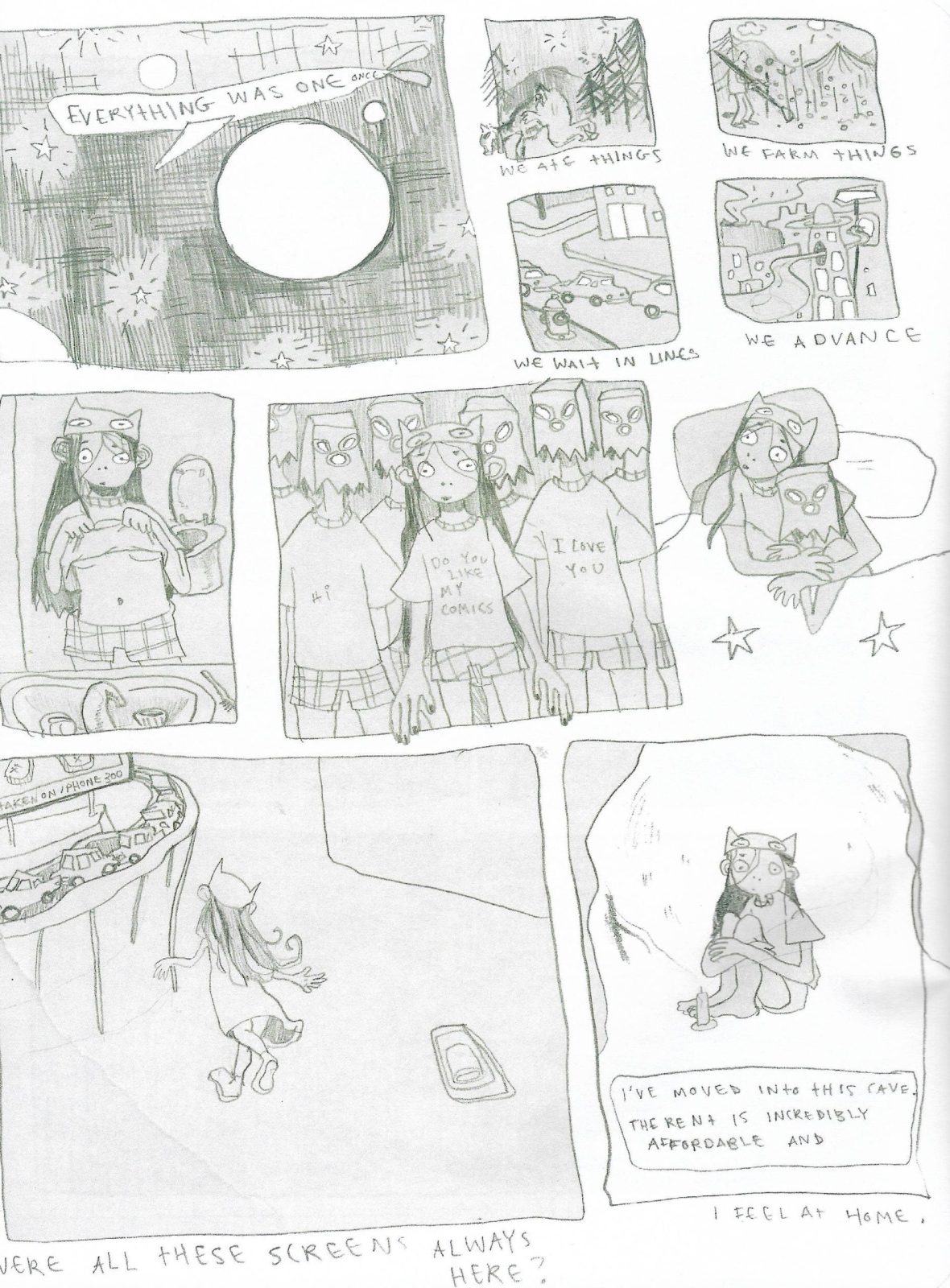

Let me start by posting some art I've liked by Jade Mar, a cartoonist who does not appear to have any active social media presence right now, but has been consistently published by Deadcrow, one of the most prolific of the new small-press outfits:

From Tinfoil Comix #1 (2020).

From Tinfoil Comix #3 (2020).

In collaboration with Simon Koza & Shen, from Tinfoil Comix #4 (2021).

From Tinfoil Comix #5 (2021).

From Cowlick Comics #1 (2022).

Squashing and stretching bodies fit to pop in smearing color; very lush. I hope you continue.

* * *

DC Narok; published by Le Dernier Cri / Timeless Editions / Hunting Asia

Cover art by Louie Cordero.

This is the catalog for an exhibition that recently closed in Marseille, the stomping grounds of notorious image-making circle Le Dernier Cri, which put on the show. They also published this book in collaboration with the fringe culture outfit Timeless Editions and Hunting Asia, the project of abrasive musician Stephen Bessac, a French expat in Thailand. The theme of the exhibition is artworks inspired by Narokphum sculpture gardens or illustration suites, which depict the torments of Hell in vivid, bloody form on the grounds of Buddhist temples in Thailand and other nations in Southeast Asia for the edification of visitors. In 2019, Timeless published an English-language book of Bessac's photos from 13 such 'hell gardens', Narok: Visions of Hell in the Kingdom of Siam, which fell into the hands of LDC's Pakito Bolino, who assembled a crew of collaborators as familiar now as the circle of artists that used to surround Monte Beauchamp's Blab!

Perhaps some familiarity is presumed. The reader of this book is presented with an alphabetical listing of the participating artists and a map of the exhibition floor, but almost no indication of which artists are responsible for which pieces; there is, arguably, a collectivist impulse behind such lack of attribution, but I also think LDC prefers exhibition catalogs such as these to function like their other books: as a blast of sensation unbothered by the complications of attribution. A French-language translation of some text from Bessac's book appears at the beginning, along with a brief French-language descriptive statement taken from the show's webpage at the end, but otherwise the reader is zoomed in and out of portions of the exhibition, looking sometimes at full reproductions of the submitted illustrations, and sometimes at photography taken on the floor of the show:

In case you've been wondering what Takashi Nemoto of Monster Men Bureiko Lullaby is up to these days, that's your answer on the left of the above image, with a glimpse to the right at a series of digital collages from the French artist Fredox, blending genitals, faces, meat and fonts; around it you can see several of the exhibition's original sculptural pieces. LDC does put together a rightly hellish and occasionally playful atmosphere—the book is an edition of 666, folks—but there is an unusual complication present.

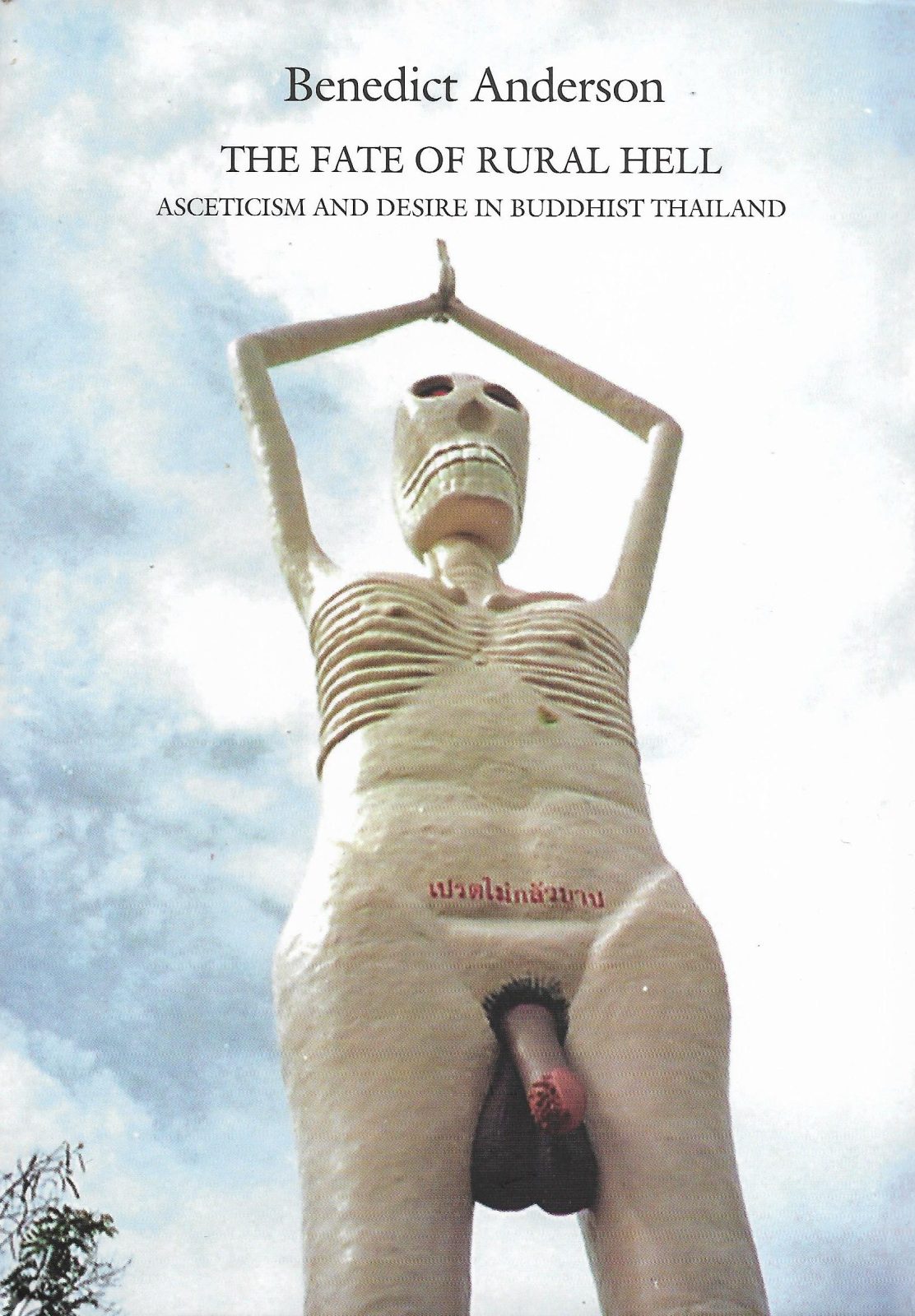

Also in the catalog are some photos from actual Narokphum setups on wat premises, which absolutely shake the surrounding material in terms of témérité du trait iconoclaste - this despite functioning as actual religious iconography. It may be the first time LDC is paying homage to a body of work as vivid and pummeling as its own, which puts les terroristes graphiques on a uniquely defensive footing. I can certainly see why Bolino would respond strongly to the Bessac book, which is entirely an exercise in novel aesthetics, "exotica" in the gawking manner of the old Italian "mondo" films. Bessac also provides a very limited text - the temples themselves are identified, with a general overview of what the gardens are and a partial guide to what some of images represent, but it is not long before Bessac gestures to an earlier, more detailed study, Benedict Anderson's The Fate of Rural Hell: Asceticism and Desire in Buddhist Thailand.

Released in English in 2012 by an Indian publisher, Seagull Books, this slim, essay-length hardcover adopts of the pose of a photographic memoir - a few of the pictures were taken by the filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul, so the book may be known already to admirers of him. Anderson focuses on perhaps the oldest of the sculpture gardens, at Wat Phai Rong Wua in Suphan Buri province; he mentions a yet-older 2010 Japanese-language book, the photographer Kyōichi Tsuzuki's Jigoku no arukkata (which Anderson wonderfully translates as "Hells that I have Walked to"), as precedent for the international fascination surrounding the gardens. Thailand and Southeast Asia was a limitless source of grotesque spectacle for Japanese 'death tapes' in the pre-streaming 1990s; those were VHS compilations of, say, roadside accidents and murder scenes - which, at least per Bessac, enjoyed their own local popularity on Thai VDC (to say nothing of western titles like Traces of Death, which were more explicitly connected to the hardcore music and edgelord zine scenes of France, USA et al.). But Anderson's analysis is a bit broader; he profiles the wat's late abbot, Luang Phor Khom, who parlayed nationalist sentiment across government coups into a decades-long massive program of temple expansion; Wat Phai Rong Wua also features, for example, the world's largest concrete Buddha statue. But the Narokphum garden, erected in the 1970s, proved unconcerned with international emulative competition, and was locally popular - and, with its many depictions of undulating nude figures, Anderson suspects it served as a source of sexual expression for the abbot. Not that these images came from nowhere - one sculptor who worked under the abbot's direction candidly notes that some of the figures were modeled off images from Thai comic books of the time.

Released in English in 2012 by an Indian publisher, Seagull Books, this slim, essay-length hardcover adopts of the pose of a photographic memoir - a few of the pictures were taken by the filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul, so the book may be known already to admirers of him. Anderson focuses on perhaps the oldest of the sculpture gardens, at Wat Phai Rong Wua in Suphan Buri province; he mentions a yet-older 2010 Japanese-language book, the photographer Kyōichi Tsuzuki's Jigoku no arukkata (which Anderson wonderfully translates as "Hells that I have Walked to"), as precedent for the international fascination surrounding the gardens. Thailand and Southeast Asia was a limitless source of grotesque spectacle for Japanese 'death tapes' in the pre-streaming 1990s; those were VHS compilations of, say, roadside accidents and murder scenes - which, at least per Bessac, enjoyed their own local popularity on Thai VDC (to say nothing of western titles like Traces of Death, which were more explicitly connected to the hardcore music and edgelord zine scenes of France, USA et al.). But Anderson's analysis is a bit broader; he profiles the wat's late abbot, Luang Phor Khom, who parlayed nationalist sentiment across government coups into a decades-long massive program of temple expansion; Wat Phai Rong Wua also features, for example, the world's largest concrete Buddha statue. But the Narokphum garden, erected in the 1970s, proved unconcerned with international emulative competition, and was locally popular - and, with its many depictions of undulating nude figures, Anderson suspects it served as a source of sexual expression for the abbot. Not that these images came from nowhere - one sculptor who worked under the abbot's direction candidly notes that some of the figures were modeled off images from Thai comic books of the time.

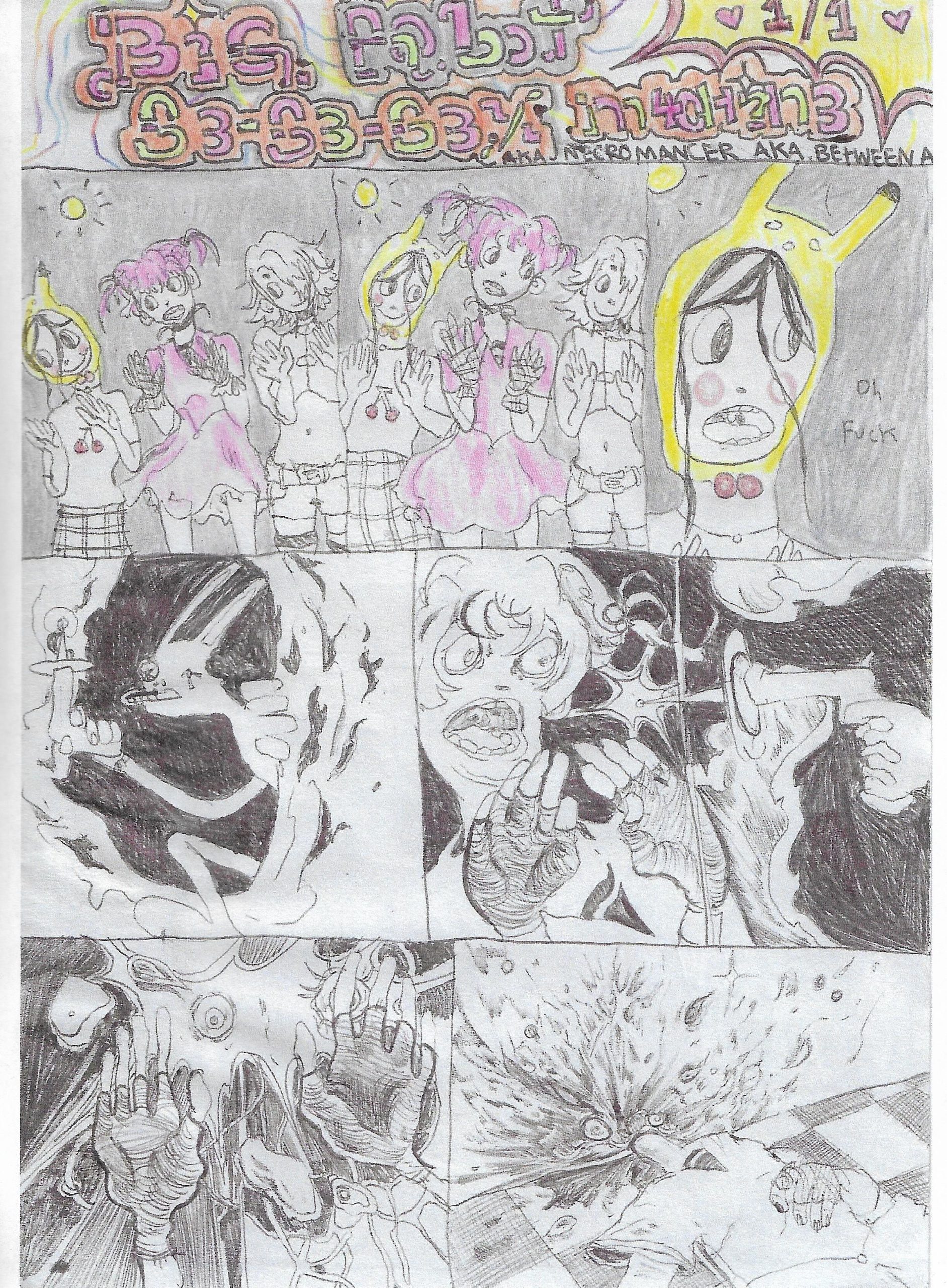

Art by Tawee Witsanukorn.

Thus, completing the circle, the DC Narok catalog devotes an ample section to Thai horror cartoonists of that era; they are the only artists in the book identified by name, perhaps in deference. Above we see an image by Tawee Witsanukorn, who purportedly defined the popular image of the mythological Krasue spirit as a woman's head trailed by oozing guts. The next stop in this never-ending chain of books should be Nicolas Verstappen's The Art of Thai Comics: A Century of Strips and Stripes (River Books, 2021), which I hope to get to soon.

* * *

Mek Memoirs Facsimile Edition by Kevin O'Neill & Chris Lowder (as "Jack Adrian"); published by Dark & Golden Books

Elsewhere in comics history, we have this 1976 self-published SF item - a 12-page fanzine notable for aiding the young artist Kevin O'Neill in getting a job as an art assistant on the nascent weekly magazine 2000 AD, which launched the following year. The present Facsimile Edition is the project of two UK art comics veterans—Douglas Noble of Strip For Me and Tom Oldham of Breakdown Press—which presents the entire original comic in simple unstapled folded paper format and wraps it in an equally-simple paper cloak of supplementary materials; it is then sealed in an illustrated envelope with a small art card depicting a nude women with large breasts observing a fight between a robot and a shark, for that authentic 'comic book store' touch.

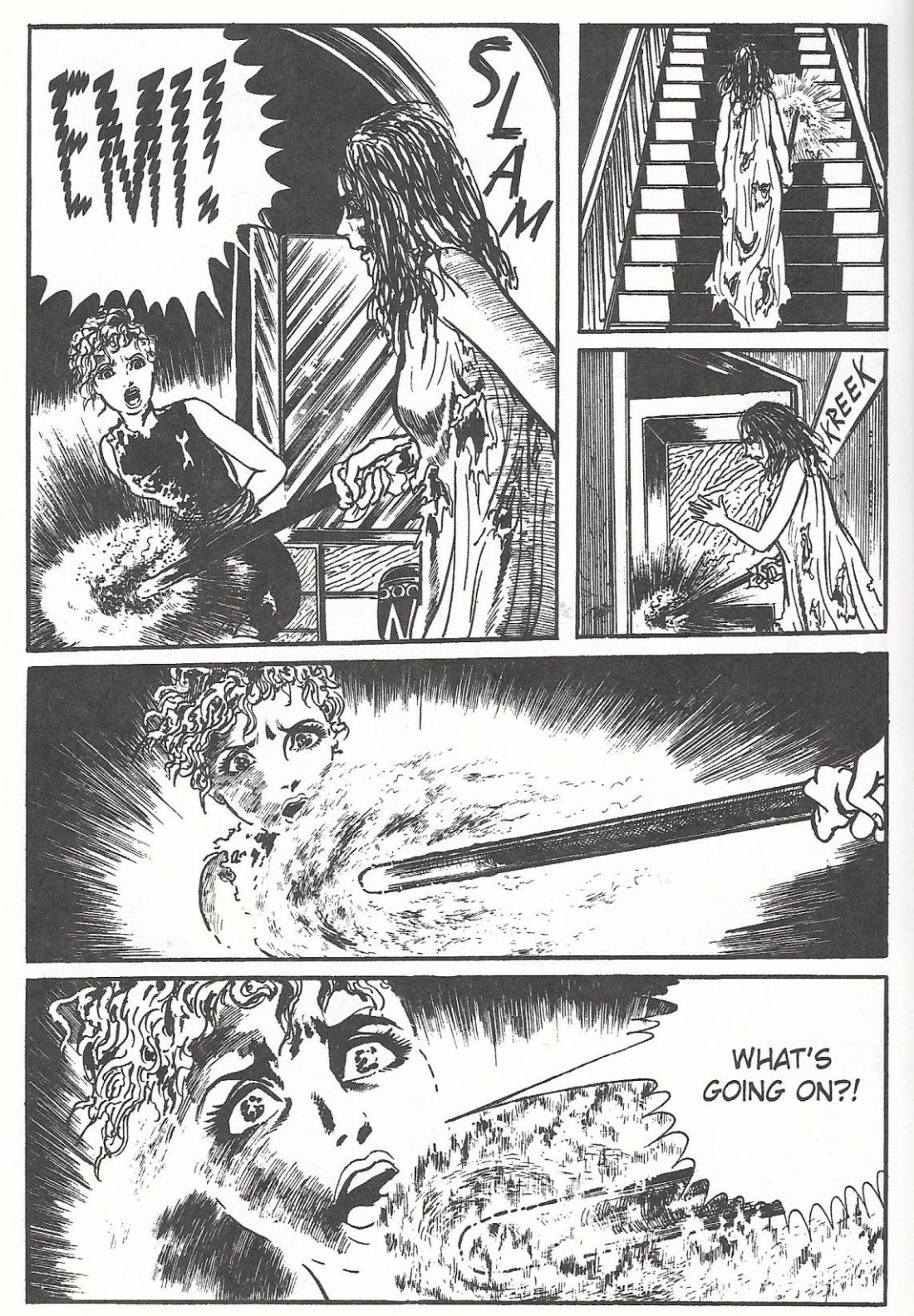

If you happen to have the 2021 expanded second edition of Cosmic Comics, the Hibernia Comics / Gosh! Comics / Treasury of British Comics collection of early O'Neill miscellany, you'll recall an anecdote in which Jan Shepheard, art editor of the weekly magazine Valiant, advises O'Neill in 1970 that it would be 10 years before he was good enough to be a proper comic book artist. I don't know if I'd go that far, but O'Neill is a bit like Mike Mignola in that it did take a while to reach the form that is characteristic of him - in this way, Mek Memoirs makes for a good companion piece to that larger volume, with the added benefit that the comic here is notably more ambitious and raw than any of the finished strips in Cosmic Comics. I mean:

While officially an unfinished serial, Mek Memoirs is notably self-contained. A distraction-prone and foul-mouthed narrator (no 2000 AD slang in here, fucker) talks along with video footage of the history of robots in combat. The footage skips around in time, relieving the young O'Neill of too much in the way of tightly sequenced images, preferring to linger instead on isolated scenes of mayhem as the Nazi-like dictator von Kruppstein pursues ambitions of conquest. But then! Upon reaching the final page, we discover that the narrator is a very dapper humanoid robot relaxing in a sort of cyber-utopia, suggesting that the meks were not just tools but sentient beings that eventually overthrew their oppressors. In its eight heavily-illustrated pages, the supplements to this edition nonetheless manage to accommodate three separate people talking shit re: the venerable UK strip Robot Archie, in which the title character is the remote slave of human operators; none of that here!

O'Neill, in truth, is still developing here as an artist, but that does allow for stronger hints of his forebears; Harvey Kurtzman registers strongly:

And so does the atmosphere of the EC Kurtzman war comics, though I'm unsure how many (if any) O'Neill had even seen by then. This is not a complicated story; every note is played big and broad, the horror of war rendered as vivid depictions of situational viciousness. The pathos of Kurtzman, though, are replaced with a very bleak irony of the sort that would soon become associated with 2000 AD in its the better strips - and, by his young lack of polish, O'Neill (but 21 when much of this was drawn) finds a vulnerable in soft flesh pressed against a jagged edge.

Panel detail.

* * *

Judge Dredd: The Citadel by John Wagner, Dan Cornwell, Dylan Teague & Annie Parkhouse; ongoing serial in 2000 AD, from Prog 2270, published by Rebellion

Panel detail.

Meanwhile, in contemporary 2000 AD, the current Judge Dredd serial is set in the midst of a Russian ("Sov") invasion of a sovereign nation, in which professionals and civilians alike are made to defend a crumbling city, the moment of warfare providing an immediate justification for a stripping away of civility and morality that will damn everyone involved. This is not unfamiliar territory for writer/co-creator John Wagner—the thus far story-length flashback is yet another take on the much-revisited early '80s Dredd favorite "The Apocalypse War", which Wagner co-wrote with Alan Grant—but the horrible synchronicity with real global events is potent enough that the magazine's cartoon alien host Tharg the Mighty issues a semi-disclaimer in Prog 2273 that this doubtlessly-finished-in-advance serial "is unfortunately more on-point than I anticipated," recommending readers turn to the rest of the magazine's features for escapism. Such are the unexpected consequences of weekly serialization. Would the Vault-Keeper have had to face the public like this if EC had lived?

* * *

"Sisters" by Kazuo Umezz (translated by Jocelyne Allen, adapted to English by Molly Tanzer, lettered by Evan Waldinger); from Orochi: The Perfect Edition Vol. 1, published by VIZ

But there's no need to be glum, chum. The most negative worldview among any of the artists in this post also belongs to its most buoyant and joyful. I can only be referring to the great Kazuo Umezz, aged 85, who recently enjoyed an enormous art exhibition in Tokyo. English translations of his work, however, remain at a trickle - VIZ re-issued his epochal The Drifting Classroom in 2019 and 2020, after many years of silence, and now brings the first of four volumes for Umezz's 1969-70 shōnen manga story sequence Orochi, which they previously tried to release in 2002 to what I can only presume was general befuddlement. These are children's comics from an era where the idea of "children's comics" was rapidly shifting to accommodate bleak and mean subjects - a situation Umezz narrates in a hysterical register, beyond the top of over-the-top, provoking a compulsive glee in the sympathetic reader.

This is inseparable from Umezz's viciousness. If there is a common theme that emerges from all of his works released in English, it is the guaranteed failure of every assurance of order in the adult world. Teachers, when placed in danger, try to kill their students. Sickly relatives curse their young caregivers. Governments facilitate ecological destruction and human exploitation, every time. Sexuality is like putting a gun to one's head, it is so laden with disastrous portent. Umezz is juvenile; his tone that of a screaming child correctly appalled at the failure of the grown-up world they are expected to inherit - so they reject everything. The idea at the center of The Drifting Classroom is that children are fated to live in the future, and its hope is that when the whole damned world is annihilated, totally destroyed, that children can build something different and better.

But us? There is no hope for us.

I am only going to focus on "Sisters", one of the two stories in this new Orochi compendium. The second, longer story, titled "Bones", concerning an abused woman's mutually-destructive distrust of her caring milquetoast husband is also good, like if the Iger Shop managed to drop an early graphic novel before the comics code came in - its disposition is very much reminiscent of Iger's writer/editor Ruth Roche and her nihilistic depiction of love and romance as a prelude to doom.

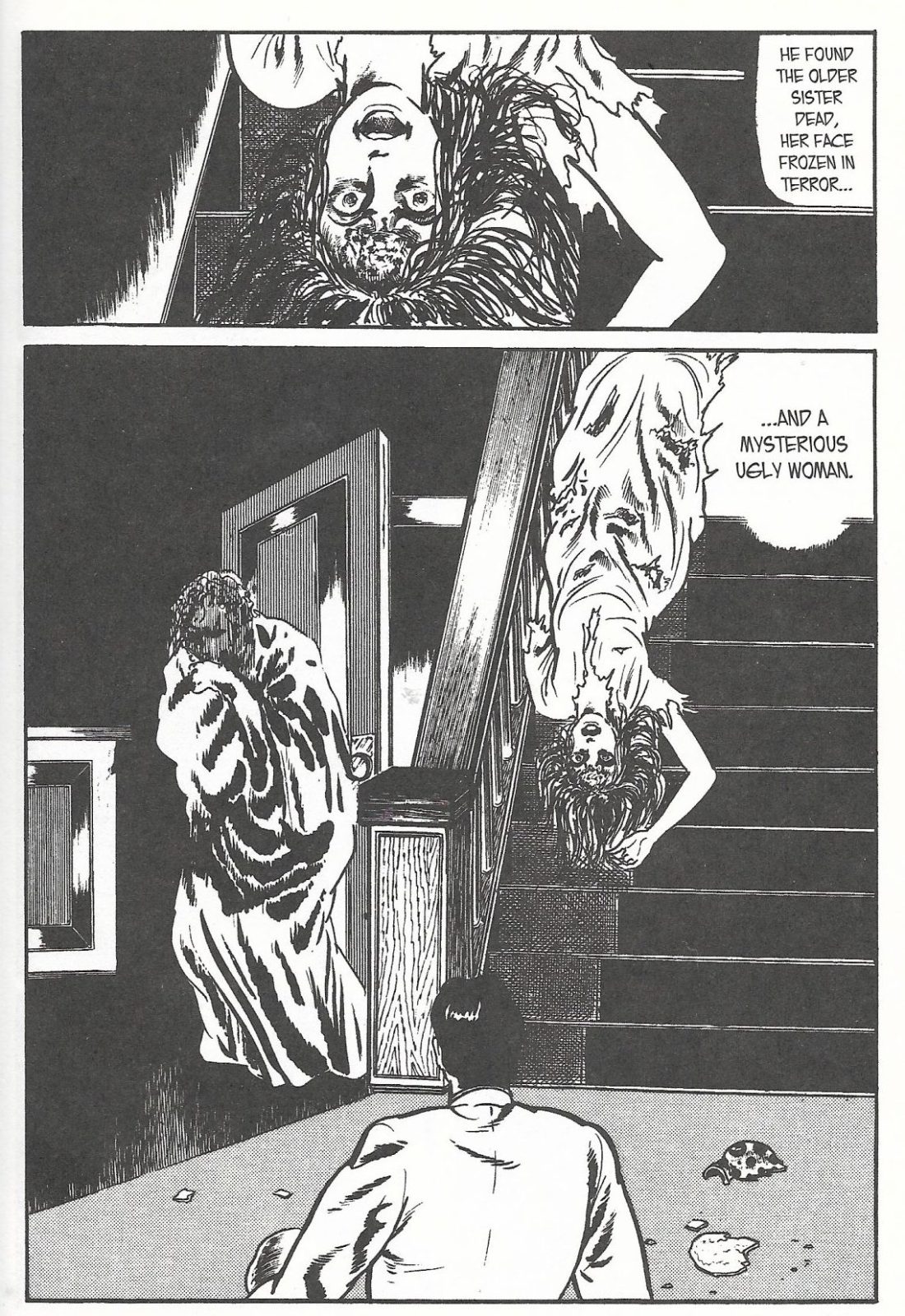

"Sisters" is more focused; the essence of simplicity. Orochi—the very amusing, supernaturally-enabled protagonist of the episodic series, who cares not for morality but can easily be moved by beauty and pathos, which she appreciates in a catastrophe-prone manner—takes a job as maid for a pair of teenaged sisters. But there is a dark secret in this house: all women of the bloodline are fated at the age of 18, the moment they are adults, to become monstrously ugly. And then, one of the sisters discovers that the other is adopted, erasing the sisterly bond in an instant and replacing it with a sort of kids' manga variant on the Onur Tukel film Catfight, where Sandra Oh and Anne Heche externalize their smothered frustrations by attacking each other to physically disfiguring and life-ruining ends. So it goes for the genetically-damned of Umezz's sisters, who understands, latently, that society will treat an unattractive woman at a disadvantage to other people, causing a complete violent break from the dull normalcy offered by her Marmaduke-like oaf boyfriend, who, when asked if he would still love his girlfriend if she were ugly, replies: "What do you mean? She's beautiful!" These gems of empathy eventually result in his lover firing a crossbow bolt into his gut, at which point Orochi must throw the man over her shoulder and walk him out of the rising action.

There is a twist at the end, which I will now ruin. It is revealed that the woman whom we thought was adopted, is actually the condemned one - she lied to her sister, knowing that she would become so hateful that she would disfigure herself through violent resentment. Such intensely misogynistic ideas; burlesque for an audience of young boys, although boys were not Umezz's only audience. Like his artistic descendant, Junji Itō, Umezz also worked extensively in girls' comics, and the sympathetic reader might take this story as an expression of socially-mandated fear of not growing into the standard of femininity, of being so ugly that nobody will ever love you (for the perspective of two woman cartoonists on this book, I would recommend the 3/28/22 episode of the Thick Lines podcast). And, there is an interesting quirk at the very end.

The idiot boyfriend returns to the heroines' house at the end of the story. The sister who disfigured herself is dead; perhaps by suicide, perhaps by sheer force of irony. Meanwhile, the condemned sister swans around the landing in a robe, glorying in her full monster form. But Umezz denies us the Basil Wolverton goods. The woman's face is completely cloaked in shadow. What she looks like, belongs only to her. Orochi approves!