children – Techdirt (original) (raw)

EU’s ‘Going Dark’ Expert Group Publishes 42-Point Surveillance Plan For Access To All Devices And Data At All Times

from the they-never-give-up dept

Techdirt has been covering the disgraceful attempts by the EU to break end-to-end encryption — supposedly in order to “protect the children” — for two years now. An important vote that could have seen EU nations back the proposal was due to take place recently. The vote was cancelled — not because politicians finally came to their senses, but the opposite. Those backing the new law were worried the latest draft might not be approved, and so removed it from the agenda, to allow a little more backroom persuasion to be applied to holdouts.

Although this “chat control” law has been the main focus of the EU’s push for more surveillance of innocent citizens, it is by no means the end of it. As the German digital rights site Netzpolitik reports, work is already underway on further measures, this time to address the non-existent “going dark” threat to law enforcement:

The group of high-level experts had been meeting since last year to tackle the so-called „going dark“ problem. The High-Level Group set up by the EU was characterized by a bias right from the start: The committee is primarily made up of representatives of security authorities and therefore represents their perspective on the issue.

Given the background and bias of the expert group, it’s no surprise that its report, “Recommendations from the High-Level Group on Access to Data for Effective Law Enforcement”, is a wish-list of just about every surveillance method. The Pirate Party Member of the European Parliament Patrick Breyer has a good summary of what the “going dark” group wants:

according to the 42-point surveillance plan, manufacturers are to be legally obliged to make digital devices such as smartphones, smart homes, IoT devices, and cars monitorable at all times (“access by design”). Messenger services that were previously securely encrypted are to be forced to allow for interception. Data retention, which was overturned by the EU Court of Justice, is to be reenacted and extended to OTT internet communications services such as messenger services. “At the very least”, IP connection data retention is to be required to be able to track all internet activities. The secure encryption of metadata and subscriber data is to be prohibited. Where requested by the police, GPS location tracking should be activated by service providers (“tracking switch”). Uncooperative providers are to be threatened with prison sentences.

It’s an astonishing list, not least for the re-appearance of data retention, which was thrown out by the EU’s highest court in 2014. It’s a useful reminder that even when bad laws are overturned, constant vigilance is required to ensure that they don’t come back at a later date.

Follow me @glynmoody on Mastodon and on Bluesky.

Filed Under: cars, chat control, children, cjeu, data retention, encryption, eu, european parliament, going dark, gps, iot, location tracking, messenger services, netzpolitik, ott, patrick breyer, pirate party, smart homes

Leading ‘Save The Kids!’ Advocate Pushing Absolutely Dangerous ‘Protect The California’ Ballot Initiative That Will Do Real Harm To Children

from the moral-panic-turned-up-to-11 dept

Over the last few years we’ve pointed out time and time again that the evidence regarding the supposed “harm” of social media to teen mental health just isn’t supported by the data. But it seems it’s never enough to stop savior-complex folks in the media, the advocacy community, and the political class from insisting it must be true. I know I just pointed this out a few days ago, but because people seem to keep missing it, let’s do it again:

- In the fall of 2022, the widely respected Pew Research Center did a massive study on kids and the internet, and found that for a majority of teens, social media was way more helpful than harmful.

- In May of 2023, the American Psychological Association (which has fallen for tech moral panics in the past, such as with video games) released a huge, incredibly detailed, and nuanced report going through all of the evidence, and finding no causal link between social media and harms to teens.

- Soon after that, the US Surgeon General came out with a report which was misrepresented widely in the press. Yet, the details of that report also showed that no causal link could be found between social media and harms to teens. It did still recommend that we act as if there were a link, which was weird and explains the media coverage, but the actual report highlights no causal link, while also pointing out how much benefit teens receive from social media).

- A few months later, an Oxford University study came out covering nearly a million people across 72 countries, noting that it could find no evidence of social media leading to psychological harm.

- The Journal of Pediatrics published a new study in the fall of 2023 again noting that after looking through decades of research, the mental health epidemic faced among young people appears largely due to the lack of open spaces where kids can be kids without parents hovering over them. That report notes that they explored the idea that social media was a part of the problem, but could find no data to support that claim.

- In November of 2023, Oxford University published yet another study, this one focused specifically on screen time, and if increased screen time was found to be damaging to kids, and found no data to support that contention.

And now we’ve got Jim Steyer, who has more money and ignorance than sense, trying to quietly push a California ballot initiative that would adjust the California constitution in an unconstitutional (by the US Constitution) manner to falsely claim that social media is deliberately harmful to kids, and that people should be able to sue social media for a million dollars any time any kid anywhere is “harmed” in a manner on social media that the social media company should have magically stopped.

He submitted the proposal on December 18th, right before the holidays when most people weren’t paying attention, and California Attorney General Rob Bonta has a comment period open that ends on January 17th (it’s initiative 23-0035, currently the top initiative) — so there’s not much time. Bonta’s office has supported a variety of problematic “protect the children online!” laws, including the Age Appropriate Design Code that a district court has already noted was pretty clearly unconstitutional (though Bonta is currently appealing that ruling). So it seems likely that Bonta will endorse Steyer’s initiative (as one does if politicians want donations from his billionaire brother).

But we should be building up a record of how completely flimsy the underlying claims in this initiative are.

Let’s look at just some of the problems (there are more, but who has the time?):

The biggest social media platforms invent and deploy features they know harm large numbers of children, including contributing to child deaths.

This is simply bullshit. Time and time again we’ve seen that “the biggest social media platforms” are regularly studying these issues and trying to mitigate harms. It’s why they have trust & safety teams, a concept these companies invented for this very reason. It’s why the studies that come out from inside these firms get so widely discussed, because it shows that the companies are studying this and trying to figure out how to minimize harm.

When you insist, falsely, that these companies are “knowingly” harming children, it leads to way more harm. Because the message here is “look the other way.” Never ever do any research that might alert you to harm, because as soon as you do, some ignorant savior complex folks are going to insist you “knowingly harmed kids.” The end result would mean less of an effort to protect kids, because that effort alone increases your liability.

Next, the initiative would lead to just a metric shit-ton of vexatious litigation:

A social media platform that knowingly violates its responsibility of ordinary care and skill to a child pursuant to subdivision (a) shall, in addition to any other remedy, be liable for statutory damages of either:

(A) one thousand dollars ($5,000) per violation up to a maximum, per child, of one million dollars ($1,000,000.); or

(B) three times the amount of the child’s actual damages.

In other words, any time a child gets bullied. Or gets depressed. Or has an eating disorder. Or dies by suicide. Or overdoses on drugs they bought via social media rather than directly from a kid at school. We’ll see lawsuits. Oh so many lawsuits. An entire industry of ambulance chasing lawyers will love every minute of this. They’ll sue for anything at all.

Rather than looking at the root cause of any of this — which again, studies have repeatedly shown is not social media at all — we’ll get lawsuits demanding $1 million per child ever time something bad happens that they can somehow, loosely, connect back to social media.

And note the even broader language here. To become liable, a site just has to “violate its responsibility of ordinary care and skill.” That is so ridiculously vague that you’ll be able to sue for basically anything. Lawyers will claim that any harm at all should have been prevented and the harm itself will be evidence of violating that responsibility.

And, based on what? Based on a near total and complete misunderstanding of the evidence which says that the entire premise of this ballot initiative is wrong and fundamentally untrue.

And, so, for the rest of this post, let’s explore Jim Steyer and Common Sense Media, because it’s worth calling out his almost Trumpian style of argumentation over this, and how it’s going to lead to real harm, completely undermining whatever “savior” legacy he has currently.

We’ve pointed out in the past that for all the good that Common Sense Media does with its ratings systems to help parents better understand the age-appropriateness of content, whenever it dips its toes into policy, it’s an embarrassment. Common Sense Media’s founder and CEO, Jim Steyer, (whose billionaire brother, Tom Steyer, ran one of 2020’s worst presidential campaigns) has spent decades acting as the wise savior of children, who insists above all that he knows best, no matter how much the evidence contradicts his views.

If you want to hear this in action, I recommend listening to this episode of “Open to Debate” from last summer exploring “Is Social Media Bad for Kids Mental Health?” Steyer took the “yes, of course,” side and was countered by psychology professor Candice Odgers. The debate is really incredible, because over and over again Dr. Odgers thoughtfully and carefully points out that the evidence just doesn’t support the claims, even if she wishes it did, as then we’d have something clear to work on. She goes into great detail on that research (as we have over and over again). And Steyer repeatedly loses his cool and basically yells “no! it’s just not true!” without being willing to cite a single piece of evidence beyond his own personal feels.

Here’s just a snippet from Odgers’ opening remarks, where you’ll note how clear and thorough she is, citing actual reports and data:

I think it’s important for everyone in the room to know, I hate social media. I don’t use it that often. I’m not a heavy user, not a fan. But I became an expert in social media and digital technology because I followed kids to the spaces where they spend their time. I wrote a report about three months ago for the National Center for the Developing Adolescent arguing for regulation around privacy, saying that social media tech companies needed to come into the Public Square and design their Tech in ways that supported our kids right?

So there I am.

But I’m standing up here tonight as a psychologist and for the last two decades of my life, I’ve studied kids mental health. Since 2008 I’ve actually followed them around on their phones — I know it sounds a little bit creepy — but tracking what they do online, what they do in school how much they sleep, how their school day went, experiences of discrimination, experiences of Mental Health.

And I’m here to tell you tonight Jim I told you in the report, but I’m here to tell you tonight that the story you’re being sold about social media and our kids’ mental health is not supported by the science.

Now don’t take my word for it. There have been thousands of studies on this topic. They’re over a hundred meta analyzes and narrative reviews. We did one in 2020 the most recent one was done at Stanford it analyzed 226 studies. Look at the association between social media and well-being. You know what they found.

The association was indistinguishable from zero.

There was no effect. And this is not an uncommon finding. Sometimes we find that social media is associated with symptoms of depression; really tiny associations. Now the important part about this and you’re all sick of hearing correlation is not causation. But in this case, it’s actually really important, because I think we’re drawing the arrow in the wrong direction.

And why I think that is if you follow kids over time — there’s a great study at 1700 kids in Canada that’s done this — followed their mental health, youth mental health, their social media use, and what you find will first for boys: there’s nothing. No association.

For girls there’s an association that’s there. But what happens is girls are experiencing mental health problems that predicts the type of social media they use; their social media use down the road but not vice versa. Social media use does not predict future mental health problems.

There’s a lot more than just this (and note that all of the studies Odgers is talking about appear to be different studies than the ones I’ve been talking about!) At this point, you have to be willfully sticking your head in the sand and deliberately ignoring the science to claim otherwise.

So how does Steyer respond? With bluster and anger and the kind of ignorant confidence of a rich man with a savior complex who just insists that Odgers must be wrong because he knows what’s true.

Look I have great respect for Candice, but the truth is, no that that simply not correct. A lot of this is just language, guys. Look and everyone out here knows this, right? What Vivek is saying, the Surgeon General, and what I’m saying is that we know that for in many many cases about in the youth Mental Health crisis that social media, various forms of it, are a major contributing factor. I’m a professor at Stanford, but I’m not an academic Candice is an academic — who we hire, by the way, and who we have great respect for — but she’s absolutely… she’s framing it in really narrow terms that academics and researchers use. By the way. I don’t even agree with some of her basic analysis, some of the research. And we will continue to hire Candace. But at the bottom line is this social media is a huge contributing factor.

I mean, it’s borderline Trumpian.

The host tries to clarify what the fuck Steyer means when he says Odgers is using “narrow terms” and his answer is borderline incoherent, and does not answer the question. He claims it has to do with how academics have “extremely specific characteristics in order to say certain things, because that’s how you actually publish studies etc. So it’s very difficult though to draw demonstrable perfect conclusions.”

Which is, um, not the point. No one is saying that they haven’t been able to draw “demonstrable perfect conclusions.” They’re saying that they have been able to draw conclusions and the conclusions say that social media isn’t causing mental health problems (and, if anything, the impact may be in the other direction).

The entire discussion goes on like that. Odgers over and over again points to “demonstrable conclusions” and Steyer gets angrier and angrier because he, the rich man, knows what the answer must be. So Odgers then points to a few more studies that debunk Steyer, and he practically yells at her (and despite earlier claiming he wasn’t an academic, now claims he is — which is a separate problem for Steyer. In another recent radio interview Steyer claimed that he is a “1st Amendment law professor,” which he absolutely is not. He was listed as an adjunct professor in the school of education).

I don’t agree with this at all. And I am I consider myself to be a scholar. I know the research, not at the level that Candice does, but I just think that’s basically an overly narrow framing of all of this. I have no issue at all as a professor and also as the head of the biggest kids advocacy group saying that the evidence is there now. The key though is that the evidence is not that it’s the only factor and it’s different in various kids, and that’s very very important. And so I could list the number of studies if you want me, that would disagree with Candice’s assessment. Because there are plenty of studies out there that show that show the oftentimes, it’s more correlation than causation. So I could go through a list of studies as well from various experts wherever…

But of course, he doesn’t. He just insists he has counter studies. Odgers points out that she would love it if her were right, because her whole focus is on helping kids deal with mental health issues, and if it really was social media, that would give her an easy tool. But the evidence just doe snot support it. And again, Steyer snaps at her.

That would be an aspect that I would tell you that just that’s just too simplistic an explanation guys. I mean and I’m being serious, I say with great respect for Candice, but I will tell you researchers are doing the public and the country a massive disservice with this nitpicking stuff and being so wishy-washy, and they have been for years. Okay? And it’s a significant problem that the researchers have been so narrow in the way they frame it. Even the most intelligent thoughtful ones like Candice.

Over and over and over it’s the same thing. Odgers, the actual academic who has devoted a large part of her professional life to studying this issue, points out what the evidence says, and Steyer gets all angry and shouty about how it’s obviously wrong and that she’s “nitpicking” or framing things “narrowly.” He says he can produce studies, but he doesn’t.

There’s also this somewhat incredible exchange later in the debate (kicked off by host John Donvan) after Odgers (again!) goes through a bunch of detailed studies and more or less points out that it’s unfair for Steyer to keep implying she doesn’t care about kids when she’s literally trying to solve hard problems by actually understanding the data:

Donvan: I’ve been hesitant to say this because it would sound like I’m taking sides. I’m definitely not. But I brief for this, and our team put together several meta studies of the studies and the overwhelming majority of them agree with Candice’s take that — and I understand you’re saying that this is maybe a problem with how they’re focusing the studies — but that they’re inconclusive on the issue of whether…

Steyer (yelling) because they’re calling for pure causation! It’s a different way of interpreting it John! You’re correct about the broad picture…

Odgers: (jumping in to point out that Steyer is just wrong here): John I’m talking about correlational studies find zero association (laughs because this is all so ridiculous)…

Steyer: (still with a raised voice) I’m sure that I find some! But… you said about what the public thinks. You know why? Because they know it’s right. if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck it is a duck and that’s what the situation is.

Donvan: Is that science? The duck?

Odgers (laughing again): No! I’m gonna study that.

Just look at how crazy this exchange is on multiple levels. Steyer (again) refuses to provide any evidence and relies on raising his voice, insistence that he must be right, or that “the public believes” it’s right, and then even pulls out the “walks like a duck” argument.

But, more importantly, there’s a real tell in that exchange. Steyer admits (falsely, as Odgers points out) that correlational studies that support his argument are enough, and that the demand for actual causation is somehow “too narrow” or a problem.

But it’s not. That’s the whole fucking point of doing science, Jim. As Odgers pointed out (if Steyer had been paying attention rather than getting all shouty), there’s real concern that the people who focus on correlation over causation are getting the causation backwards.

Remember that Journal of Pediatrics study we pointed to a few months back? What those researchers found was that it was the lack of spaces where “kids could be kids” (without parents hovering over them at all times) that the data showed was the largest factor contributing to mental health problems in teens (and they also pointed out there was no evidence that social media was contributing to the problem).

Once you understand that you realize how important causation is here, because the data suggests (Jim!) that the reason some kids flock to social media is that they have fewer and fewer spaces to interact with their peers and to just be kids. And thus, the reports (which Odgers also highlighted) suggesting that the prediction runs the other way (i.e., those with more serious mental health problems retreat to social media) suggest that they do so because they have nowhere else to turn. Nowhere else to get help. Nowhere else to just be themselves.

And it’s savior complex folks who insist that kids need to be monitored and restricted 24/7 that have created that world and helped to create these very problems.

Yet people like Steyer refuse to see this and just keep getting crazier and crazier. In the debate, Odgers and Donvan point out that this seems like the same moral panic of days gone by: rock and roll, television, comic books, radio, cable TV, pinball… all were said to melt kids’ brains. And Steyer loses his shit yet again and,, in a moment that really drives home his lack of self-awareness, claims that only people who aren’t well informed would say this:

That is simply not correct! And and the answer is to draw a comparison between television and social media is like a joke to me. Having said it, many people say what you just said, John. They tend to be not familiar with what’s really going on with the issue…

Just incredible.

There’s a lot more and it’s all the same. Odgers, the actual expert, presenting actual evidence and explaining things with nuance. And Steyer, the overly confident savior, insisting that everyone else is wrong and only he knows what’s really happening.

And, normally, we’d expect common sense (see what I did there?) to win out in the end, but this isn’t about common sense. As we’ve discussed before, California ballot initiatives are a ridiculously dangerous tool. As long as you have enough money and the ability to frame a moral panic the way you want to, you can get the votes.

Who doesn’t want to “protect the children?” And Steyer has the money at his disposal to get the signatures to get this issue on the ballot, and can easily frame it (as he himself admits) that the public perception here of harm from social media to kids is the reality — even as the actual data keeps saying they’re wrong.

So please consider commenting (politely please!) on Bonta’s review of this awful state initiative. I doubt it will stop the initiative from going forward. Chances are this thing has a real chance to get added to the California constitution, despite the fact that it’s built on a foundation of debunked moral panics. And, even worse, as we’ve seen, once a California ballot initiative goes through it’s nearly impossible to fix.

Steyer’s plan here will do real harm to the very children he wants to claim he’s saving. Please speak out to stop this attempt to capitalize on an anti-intellectual moral panic to allow someone to pretend he’s helping to save the kids while actually doing very real harm.

Filed Under: ballot initiatives, california, candice odgers, children, harms, jim steyer, mental health, rob bonta, save the children, social media

Companies: common sense media

Tim Wu Asks Why Congress Keeps Failing To Protect Kids Online. The Answer Is That He’s Asking The Wrong Question

from the wrong-question,-dumb-answer dept

While I often disagree with Tim Wu, I like and respect him, and always find it interesting to know what he has to say. Wu was also one of the earliest folks to give me feedback on my Protocols not Platforms paper, when he attended a roundtable at Columbia University discussing early drafts of the papers in that series.

Yet, quite frequently, he perplexes me. The latest is that he’s written up a piece for The Atlantic wondering “Why Congress Keeps Failing to Protect Kids Online.”

The case for legislative action is overwhelming. It is insanity to imagine that platforms, which see children and teenagers as target markets, will fix these problems themselves. Teenagers often act self-assured, but their still-developing brains are bad at self-control and vulnerable to exploitation. Youth need stronger privacy protections against the collection and distribution of their personal information, which can be used for targeting. In addition, the platforms need to be pushed to do more to prevent young girls and boys from being connected to sexual predators, or served content promoting eating disorders, substance abuse, or suicide. And the sites need to hire more staff whose job it is to respond to families under attack.

Of course, let’s start there. The “case for legislative action” is not, in fact, overwhelming. Worse, the case that the internet harms kids is… far from overwhelming. The case that it helps many kids is, actually, pretty overwhelming. We keep highlighting this, but the actual evidence does not, in any way, suggest that social media and the internet are “harming” kids. It actually says the opposite.

Let’s go over this again, because so many people want to ignore the hard facts:

- Last fall, the widely respected Pew Research Center did a massive study on kids and the internet, and found that for a majority of teens, social media was way more helpful than harmful.

- This past May, the American Psychological Association (which has fallen for tech moral panics in the past, such as with video games) released a huge, incredibly detailed, and nuanced report going through all of the evidence, and finding no causal link between social media and harms to teens.

- Soon after that, the US Surgeon General (in the same White House where Wu worked for a while) came out with a report which was misrepresented widely in the press. Yet, the details of that report also showed that no causal link could be found between social media and harms to teens. It did still recommend that we act as if there were a link, which was weird and explains the media coverage, but the actual report highlights no causal link, while also pointing out how much benefit teens receive from social media).

- A few months later, an Oxford University study came out covering nearly a million people across 72 countries, noting that it could find no evidence of social media leading to psychological harm.

- The Journal of Pediatrics just published a new study again noting that after looking through decades of research, the mental health epidemic faced among young people appears largely due to the lack of open spaces where kids can be kids without parents hovering over them. That report notes that they explored the idea that social media was a part of the problem, but could find no data to support that claim.

What most of these reports did note is that there is some evidence that for some very small percentage of the populace who are already dealing with other issues, those issues can be exacerbated by social media. Often, this is because the internet and social media become a crutch for those who are not receiving the help that they need elsewhere. However, far more common is that the internet is tremendously helpful for kids trying to figure out their own identity, to find people they feel comfortable around, and to learn about and discover the wider world.

So, already, the premise is problematic that the internet is inherently harmful for children. The data simply does not support that.

None of this means that we shouldn’t be open to ways to help those who really need it. Or that we shouldn’t be exploring better regulations for privacy protection (not just for kids, but for everyone). But this narrative that the internet is inherently harmful is simply not supported by the data, even as Wu and others seem to pretend it’s clear.

Wu does mention the horror stories he heard from some parents while he was in the White House. And those horror stories do exist. But most of those horror stories are similar to the rare, but still very real, horror stories facing kids offline as well. We should be looking for ways to deal with those rare but awful stories, but that doesn’t mean destroying all of the benefits of online services in the meantime.

And that brings us to the second problem with Wu’s setup here. He then pulls out the “something must be done, this is something, we should do this” approach to solving the problem he’s already misstated. In particular, he suggests that Congress should support KOSA:

A bolder approach to protecting children online sought to require that social-media platforms be safer for children, similar to what we require of other products that children use. In 2022 the most important such bill was the Kid’s Online Safety Act (KOSA), co-sponsored by Senators Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut and Marcia Blackburn of Tennessee. KOSA came directly out of the Frances Haugen hearings in the summer of 2021, and particularly the revelation that social-media sites were serving content that promoted eating disorders, suicide, and substance abuse to teenagers. In an alarming demonstration, Blumenthal revealed that his office had created a test Instagram account for a 13-year-old girl, which was, within one day, served content promoting eating disorders. (Instagram has acknowledged that this is an ongoing issue on its site.)

The KOSA bill would have imposed a general duty on platforms to prevent and mitigate harms to children, specifically those stemming from self-harm, suicide, addictive behaviors, and eating disorders. It would have forced platforms to install safeguards to protect children and tools to enable parental supervision. In my view, the most important thing the bill would have done was simply force the platforms to spend more money and more ongoing attention on protecting children, or risk serious liability.

But KOSA became a casualty of the great American culture war. The law would give parents more control over what their children do and see online, which was enough for some groups to transform the whole thing into a fight over transgender issues. Some on the right, unhelpfully, argued that the law should be used to protect children from trans-related content. That triggered civil-rights groups, who took up the cause of teenage privacy and speech rights. A joint letter condemned KOSA for “enabl[ing] parental supervision of minors’ use of [platforms]” and “cutting off another vital avenue of access to information for vulnerable youth.”

It got ugly. I recall an angry meeting in which the Eating Disorders Coalition (in favor of the law) fought with LGBTQ groups (opposed to it) in what felt like a very dark Veep episode, except with real lives at stake. Critics like Evan Greer, a digital-rights advocate, charged that attorneys general in red states could attempt to use the law to target platforms as part of a broader agenda against trans rights. That risk is exaggerated. The bill’s list of harms is specific and discrete; it does not include, say, “learning about transgenderism,” but it does provide that “nothing shall be construed [to require a platform to prevent] any minor from deliberately and independently searching for, or specifically requesting, content.” Nonetheless, the charge had a powerful resonance and was widely disseminated.

This whole thing is quite incredible. KOSA did not become a “casualty of the great American culture war.” Wu, astoundingly, downplays that both the Heritage Foundation and the bill’s own Republican co-author, Marsha Blackburn, directly said that the will would be helpful in censoring transgender information. For Wu to then say that the bill’s own co-author is wrong about what her own bill does is quite incredible.

He’s also wrong. While it is correct that the bill lists out six designated categories of harmful information that must be blocked, he leaves out that it’s the state Attorneys’ General who get to decide. And if you’ve paid attention to anything over the last decade, it’s that state AGs are inherently political, and are some of the most active “culture warriors” out there, quite willing to twist laws to their own interpretation to get headlines.

Also, even worse, as we’ve explained over and over again, laws like these that do require “mitigation” of “harmful content” around things like “eating disorders,” often fail to understand how that content works. As we’ve detailed, Instagram and Facebook made a big effort to block “eating disorder” content, and it backfired in a huge way. First, the issue wasn’t social media driving people to eating disorders, but people seeking out information on eating disorders (in other words, it was a demand side, not a supply side, problem).

So, when that content was removed, people with eating disorders still sought out the same content, and they still found it, either by using code words to get around the blocks or moving to darker, and even more problematic forums, where the people who ran them were way worse. And one result of this was that those forums lost the actually useful forms of mitigation, which include people talking to the kids and helping them get the help they need.

So here we have Tim Wu misunderstanding the problem, misunderstanding the solution he’s supporting (such that he’s supporting an idea already shown to make the problem worse), and he asks why Congress isn’t doing anything? Really?

It doesn’t help that there has been no political accountability for the members of Congress who were happy to grandstand about children online and then do nothing. No one outside a tiny bubble knows that Wicker voted for KOSA in public but helped kill it in private, or that infighting between Cantwell and Pallone helped kill children’s privacy. I know this only because I had to for my job. The press loves to cover members of Congress yelling at tech executives. But its coverage of the killing of popular bills is rare to nonexistent, in part because Congress hides its tracks. Say what you want about the Supreme Court or the president, but at least their big decisions are directly attributable to the justices or the chief executive. Congressmen like Frank Pallone or Roger Wicker don’t want to be known as the men who killed Congress’s efforts to protect children online, so we rarely find out who actually fired the bullet.

Notice that Wu never considers that the bills might be bad and didn’t deserve to move forward?

But Wu has continued to push this, including on exTwitter, in which he attacks those who have presented the many problematic aspects of KOSA, suggesting that they’re simply ignoring the harms. They’re not. Wu is ignoring the harms of what he supports.

Again, while I often disagree with Wu, I usually find he argues in good faith. The argument in this piece, though, is just utter nonsense. Do better.

Filed Under: children, congress, duty of care, eating disorders, kosa, privacy, social media, think of the children, tim wu

KOSA Won’t Make The Internet Safer For Kids. So What Will?

from the let's-think-this-through dept

I’ve been asked a few times now what to do about online safety if the Kids Online Safety Act is no good. I will take it as a given that not enough is being done to make the Internet safe, especially for children. I think there is enough evidence to show that while the Internet can be a positive for many young people, especially marginalized youth that find support online, there are also significant negatives that correlate to real world harms that lead to suffering.

As I see it, there are three separate but related problems:

- Most Internet companies make money off engagement, and so there can be misaligned incentives especially when some toxic things can drive engagement.

- Trust & Safety is the linchpin of efforts to improve online safety, but it represents a significant cost to companies without a direct connection to profit.

- The tools used by Trust & Safety, like content moderation, have become a culture war football and many – including political leaders – are trying to work the refs.

I think #1 tends to be overstated, but X/Twitter is a natural experiment on whether this model is successful in the long run so we may soon have a better answer. I think #2 is understated, but it’s a bit hard to find government solutions here – especially those that don’t run into First Amendment concerns. And #3 is a bit of a confounding problem that taints all proposed solutions. There is a tendency to want to use “online safety” as an excuse to win culture wars, or at least tack culture war battles onto legitimate attempts to make the Internet safer. These efforts run headfirst into the First Amendment, because they are almost exclusively about regulating speech.

KOSA’s main gambit is to discourage #1 and maybe even incentivize #2 by creating a sort of nebulous duty of care that basically says if companies don’t have users’ best interests at heart in six described areas then they can be sued by the FTC and State AGs. The problem is that the duty of care is largely directed at whether minors are being exposed to certain kinds of content, and this invites problem #3 in a big way. In fact, we’ve already seen politically connected anti-LGBTQ organizations like Heritage openly call for KOSA to be used against LGBTQ content and Senator Blackburn, a KOSA co-author, connected the bill with protecting “minor children from the transgender.” This also means that this part of KOSA is likely to eventually fall to the First Amendment, as the California Age Appropriate Design Code (a bill KOSA borrows from) did.

So what can be done? I honestly don’t think we have enough information yet to really solve many online safety problems. But that doesn’t mean we have to sit around doing nothing. Here are some ideas of things that can be done today to make the Internet safer or prepare for better solutions in the future:

Ideas for Solving Problem #1

- Stronger Privacy: Having a strong baseline of privacy protections for all users is good for many reasons. One of them is breaking the ability of platforms to use information gathered about you to keep you on the platform longer. Many of the recommendation engines that set people down a bad path are algorithms powered by personal information and tuned to increase engagement. These algorithms don’t really care about how their recommendations affect you, and can send you in directions you don’t want to go but have trouble turning away from. I experienced some of this myself when using YouTube to get into shape during the pandemic. I was eventually recommended videos that body shamed and recommended pretty severe diets to “show off” your muscles. I was able to reorient the algorithm towards more positive and health-centered videos, but it took some degree of effort and understanding how things worked. If the algorithm wasn’t powered by my entire history, and instead had to be more user directed, I don’t think I’d be offered the same content. And if I did look for that content, I’d be able to do so more deliberately and carefully. Strong privacy controls would force companies to redesign in that way.

- An FTC 6(b) study: The FTC has the authority to conduct wide-ranging industry studies that don’t need a specific law enforcement purpose. In fact, they’ve used their 6(b) authority to study industries and produce reports that help Congress legislate. This 6(b) authority includes subpoena power to get information that independent researchers currently can’t. KOSA has a section that allows independent researchers to better study harms related to the design of online platforms, and I think that’s a pretty good idea, but the FTC can start this work now. A 6(b) study doesn’t need Congressional action to start, which is good considering the House is tied up at the moment. They can examine how companies work through safety concerns in product design, look for hot docs that show they made certain design decisions despite known risks, or look for mid docs that show they refused to look into safety concerns.

- Enhance FTC Section 5 Authority: The FTC has already successfully obtained a settlement based on the argument that certain harmful design choices violate Section 5’s prohibition of “unfair or deceptive” business practices. The settlement required Epic to turn off voice and text chat in the game Fortnite for children and teens by default. Congress could enhance this power by clarifying that Section 5 includes dangerous online product design more generally and require the FTC to create a division for enforcement in this area (and also increase the FTC’s budget for such staffing). A 6(b) study would also lay the groundwork for the FTC to take more actions in this area. However, any legislation should be drafted in a way that does not undercut the FTC’s argument that it already has much of this authority, as doing so would discourage the FTC from pursuing more actions on its own. This is another option that likely does not need Congressional action, but budget allocations and an affirmative directive to address this area would certainly help.

- NIH/other agency studies: Another way to help the FTC to pursue Section 5 complaints against dangerous design, and improve the conversation generally, is to invest in studies from medical and psychological health experts on how various design choices impact mental health. This can set a baseline of good practices from which any significant deviation could be pursued by the FTC as a Section 5 violation. It could also help policy discussions coalesce around rules concerning actual product design rather than content. The NTIA’s current request for information on Kids Online Health might be a start to that. KOSA’s section on creating a Kids Online Safety Council is another decent way of accomplishing this goal. Although, the Biden administration could simply create such a Council without Congressional action, and that might be a better path considering the current troubles in the House. I should also point out that this option is ripe for special interest capture, and that any efforts to study these problems should include experts and voices from marginalized and politically targeted communities.

- Better User Tools: I’ve written before on concerns I had with an earlier draft of KOSA’s parental tools requirements. I think that section of the bill is in a much better place now. Generally, I think it’s good to improve the resources parents have to work with their kids to build a positive online social environment. It would also be good to have tools for users to help them have a say in what content they are served and how the service interacts with them (i.e. turning off nudges). That might come from a law establishing a baseline for user tools. It might also come from an agency hosting discussions on and fostering the development of best practices for such tools. I will again caution though that not all parents have their kids’ best interests at heart, and kids are entitled to privacy and First Amendment rights. Any work on this should keep that in mind, and some minors may need tools to protect themselves from their parents.

- Interoperability: One of the biggest problems for users who want to abandon a social media platform is how hard it is to rebuild their network elsewhere. X/Twitter is a good example of this, and I know many people that want to leave but have trouble rebuilding the same engagement elsewhere. Bluesky and Mastodon are examples of newer services that offer some degree of interoperability and portability of your social graph. The advantages of that are obvious, creating more competition and user choice. This is again something the government could support by encouraging standards or requiring interoperability. However, as Bluesky and Mastodon have shown, there has been a problem with interoperable platforms and content moderation because it’s a large cost not directly related to profit. This remains a problem to be solved. Ideally a strong market for effective third party content moderation should be created, but this is not something the government can be involved in because of the obvious First Amendment problems.

Ideas for Solving Problem #2

- Information sharing: When I went to TrustCon this year the number one thing I heard was that T&S professionals need better information sharing – especially between platforms. This makes perfect sense: it lowers the cost of enforcement and improves the quality of enforcement. The kind of information we are talking about are emerging threats and the most effective ways of dealing with them. For example, coded language people are adopting to get around filters to catch sexual predation on platforms with minors. There are ways that the government can foster this information sharing at the agency level by, for example, hosting workshops, roundtables, and conferences geared towards T&S professionals on online safety. It would also be helpful for agencies to encourage “open source” information for T&S teams to make it easier for smaller companies.

- Best Practices: Related to other solutions above, a government agency could engage the industry and foster the development of best practices (as long as they are content-agnostic), and a significant departure of those best practices could be challenged as a violation of Section 5 of the FTC Act. Those best practices should include some kind of minimum for T&S investment and capabilities. I think this could be done under existing authority (like the Fortnite case), although that authority will almost certainly be challenged at some point. It might be better for Congress to affirmatively task agencies with this duty and allocate appropriate funding for them to succeed.

Ideas for Solving Problem #3

- Keeping the focus on product design: Problem #3 is never going away, but the best way to minimize its impacts AND lower the risk of efforts getting tossed on First Amendment grounds is to keep every public action on online safety firmly grounded in product design. That means every study, every proposed rulemaking, and every introduced bill needs to be first examined with a basic question: “does this directly or indirectly create requirements based on speech, or suggest the adoption of practices that will impact speech.” Having a good answer to this question is important, because the industry will challenge laws and regulations on First Amendment grounds, so any laws and regulations must be able to survive those challenges.

- Don’t Undermine Section 230: Section 230 is what enables content moderation work at scale, and online safety is mostly a content moderation problem. Without Section 230 companies won’t be able to experiment with different approaches to content moderation to see what works. This is obviously a problem because we want them to adopt better approaches. I mention this here because some political leaders have been threatening Section 230 specifically as part of their attempts to work the refs and get social media companies to change their content moderation policies to suit their own political goals.

Matthew Lane is a Senior Director at InSight Public Affairs.

Filed Under: children, internet safety, kosa, parental tools, privacy

As Congress Rushes To Force Websites To Age Verify Users, Its Own Think Tank Warns There Are Serious Pitfalls

from the a-moral-panic-for-the-ages dept

We’re in the midst of a full blown mass hysteria moral panic claiming that the internet is “dangerous” for children, despite little evidence actually supporting that hypothesis, and a ton arguing the opposite is true. States are passing bad laws, and Congress has a whole stack of dangerous “for the children” laws, from KOSA to the RESTRICT Act to STOP CSAM to EARN IT to the Cooper Davis Act to the “Protecting Kids on Social Media Act” to COPPA 2.0. There are more as well, but these are the big ones that all seem to be moving through Congress.

The NY Times has a good article reminding everyone that we’ve been through this before, specifically with Reno v. ACLU, a case we’ve covered many times before. In the 1990s, a similar evidence-free mass hysteria moral panic about the internet and kids was making the rounds, much of it driven by sensational headlines and stories that were later debunked. But Congress, always happy to announce they’ve “protected the children,” passed the Communications Decency Act from Senator James Exon, which he claimed would clean up all the smut he insisted was corrupting children (he famously carried around a binder full of porn that he claimed was from the internet to convince other Senators).

You know what happened next: the Supreme Court (thankfully) remembered that the 1st Amendment existed, and noted that it also applied to the internet, and Exon’s Communications Decency Act (everything except for the Cox/Wyden bit which is now known as Section 230) got tossed out as unconstitutional.

It remains bizarre to me that all these members of Congress today don’t seem to recognize that the ruling in ACLU v. Reno existed, and how all their laws seem to ignore it. But perhaps that’s because it happened 25 years ago and their memories don’t stretch back that far.

But, the NY Times piece ends with something a bit more recent: it points to an interesting Congressional Research Service report that basically tells Congress that any attempt to pass a law targeting minors online will have massive consequences beyond what these elected officials intend.

As we’ve discussed many times in the past, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) is Congress’ in-house think tank, which is well known for producing non-political, very credible research, which is supposed to better inform Congress, and perhaps stop them from passing obviously problematic bills that they don’t understand.

The report focuses on age verification techniques, which most of these laws will require (even though some of them pretend not to: the liability for failure will drive many sites to adopt it anyway). But the CRS notes, it’s just not that easy. Almost every solution out there has real (and serious) problems, either in how well they work, or what they mean for user privacy:

Providers of online services may face different challenges using photo ID to verify users’ ages, depending on the type of ID used. For example, requiring a government-issued ID might not be feasible for certain age groups, such as those younger than 13. In 2020, approximately 25% and 68% of individuals who were ages 16 and 19, respectively, had a driver’s license. This suggests that most 16 year olds would not be able to use an online platform that required a driver’s license. Other forms of photo ID, such as student IDs, could expand age verification options. However, it may be easier to falsify a student ID than a driver’s license. Schools do not have a uniform ID system, and there were 128,961 public and private schools—including prekindergarten through high school—during the 2019-2020 school year, suggesting there could be various forms of IDs that could make it difficult to determine which ones are fake.

Another option could be creating a national digital ID for all individuals that includes age. Multiple states are exploring digital IDs for individuals. Some firms are using blockchain technologies to identify users, such as for digital wallets and for individuals’ health credentials. However, a uniform national digital ID system does not exist in the United States. Creating such a system could raise privacy and security concerns, and policymakers would need to determine who would be responsible for creating and maintaining the system, and verifying the information on it—responsibilities currently reserved to the states.

Several online service providers are relying on AI to identify users’ ages, such as the services offered by Yoti, prompting firms to offer AI age verification services. For example, Intellicheck uses facial biometric data to validate an ID by matching it to the individual. However, AI technologies have raised concerns about potential biases and a lack of transparency. For example, the accuracy of facial analysis software can depend on the individual’s gender, skin color, and other factors. Some have also questioned the ability of AI software to distinguish between small differences in age, particularly when individuals can use make-up and props to appear older.

Companies can also rely on data obtained directly from users or from other sources, such as data brokers. For example, a company could check a mobile phone’s registration information or analyze information on the user’s social media account. However, this could heighten data privacy concerns regarding online consumer data collection.

In other words, just as the French data protection agency found, there is no age verification solution out there that is actually safe for people to rely on. Of course, that hasn’t stopped moral panicky French lawmakers from pushing forward with a requirement for one anyway, and it looks like the US Congress will similarly ignore its own think tank, and Supreme Court precedent, and push forward with their own versions as well.

Hopefully, the Supreme Court actually remembers how all this works.

Filed Under: age verification, children, crs, free speech, kosa, protect the children, restrict act, stop csam

Utah’s Governor Live Streams Signing Of Unconstitutional Social Media Bill On All The Social Media Platforms He Hates

from the utah-gets-it-wrong-again dept

On Thursday, Utah’s governor Spencer Cox officially signed into law two bills that seek to “protect the children” on the internet. He did with a signing ceremony that he chose to stream on nearly every social media platform, despite his assertions that those platforms are problematic.

Yes, yes, watch live on the platforms that your children shouldn’t use, lest they learn that their governor eagerly supports blatantly unconstitutional bills that suppress the free speech rights of children, destroy their privacy, and put them at risk… all while claiming he’s doing this to “protect them.”

The decision to sign the bills is not a surprise. We talked about the bills earlier this year, noting just how obviously unconstitutional they are, and how much damage they’d do to the internet.

The bills (SB 152 and HB 311) do a few different things, each of which is problematic in its own special way:

- Bans anyone under 18 from using social media between 10:30pm and 6:30am.

- Requires age verification for anyone using social media while simultaneously prohibiting data collection and advertising on any “minor’s” account.

- Requires social media companies to wave a magic wand and make sure no kids get “addicted” with addiction broadly defined to include having a preoccupation with a site that causes “emotional” harms.

- Requires parental consent for anyone under the age of 18 to even have a social media account.

- Requires social media accounts to give parents access to their kids accounts.

Leaving aside the fun of banning data collection while requiring age verification (which requires data collection), the bill is just pure 100% nanny state nonsense.

Children have their own 1st Amendment rights, which this bill ignores. It assumes that teenagers have a good relationship with their parents. Hell, it assumes that parents have any relationship with their kids, and makes no provisions for how to handle cases where parents are not around, have different names, are divorced, etc.

Also, the lack of data collection combined with the requirement to prevent addiction creates a uniquely ridiculous scenario in which these companies have to make sure they don’t provide features and information that might lead to “addiction,” but can’t monitor what’s happening on those accounts, because it might violate the data collection restrictions.

As far as I can tell, the bill both requires social media companies to hide dangerous or problematic content from children, and blocks their ability to do so.

Because Utah’s politicians have no clue what they’re doing.

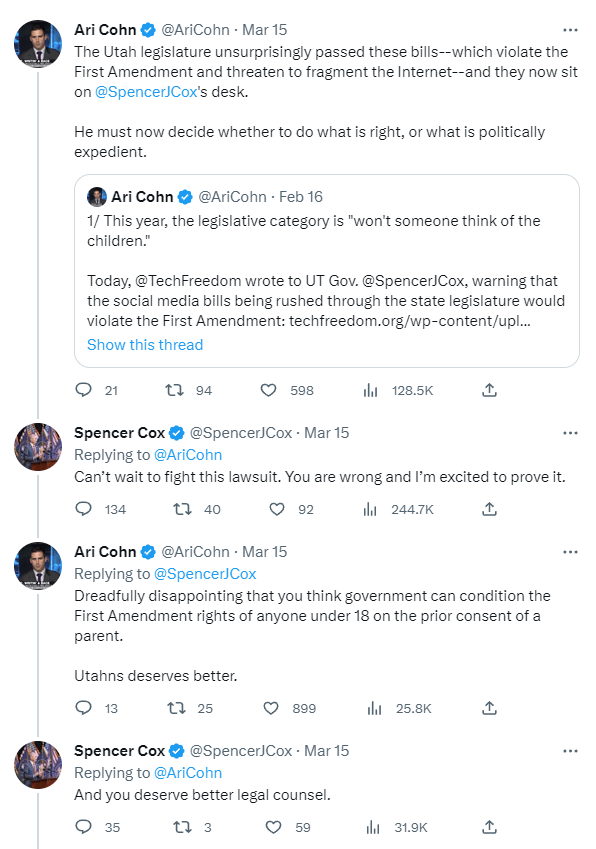

Meanwhile, Governor Cox seems almost gleeful about just how unconstitutional his bill is. After 1st Amendment/free speech lawyer Ari Cohn laid out the many Constitutional problems with the bill, Cox responded with a Twitter fight, by saying he looked forward to seeing Cohn in court.

Perhaps Utah’s legislature should be banning itself from social media, given how badly they misunderstand basically everything about it. They could use that time to study up on the 1st Amendment, because they need to. Badly.

Anyway, in a de facto admission that these laws are half-baked at best, they don’t go into effect until March of 2024, a full year, as they seem to recognize that to avoid getting completely pantsed in court, they might need to amend them. But they are going to get pantsed in court, because I can almost guarantee there will be constitutional challenges to these bills before long.

Filed Under: 1st amendment, age verification, children, parental permission, parents, privacy, protect the children, social media, social media bans, spencer cox, utah

NYPD Says Kids Don’t Need Lawyers While Fighting Reforms Targeting Interrogations Of Minors

from the all-lawyers-do-is-make-us-respect-rights! dept

Leave it to the NYPD to suggest some people’s rights just don’t matter. The NYPD has resisted pretty much every reform effort shoved in its general direction and this one — which would affect questioning of juvenile detainees — is being resisted as well. (“Stop resisting!” only works in one direction, unfortunately.)

Here’s C.J. Ciaramella with more details for Reason:

The City recently reported that a coalition of public defenders, juvenile justice organizations, and other groups are pushing to pass a bill in the next session of the New York Legislature that would require minors speak with a lawyer before they waive their Miranda rights and talk to police.

If such a bill passed, New York would join several other states that have tightened rules for juvenile interrogations in recent years. Both Maryland and Washington passed laws requiring attorney consultations for minors before interrogations. Last year, Illinois became the first state in the U.S. to ban police from lying to minors during interrogations. Oregon followed suit shortly after.

It’s a simple reform: one that ensures minors receive the same constitutional protections adults do when detained by police. There’s no reason they shouldn’t have these protections. While the rights of minors can sometimes be slightly diminished to ensure things like school safety, their rights when arrested by police officers remain exactly the same as every other American.

All this would do is force the NYPD to give juveniles access to lawyers during questioning — the same demand that can be made by anyone under arrest. The NYPD ain’t having it, though. And, as Ciaramella points out, the statement it gave The City suggests it thinks children should be underserved when arrested, unable to fully utilize their constitutional rights.

“Parents and guardians are in the best position to make decisions for their children, and this bill, while well-intentioned, supplants the judgment of parents and guardians with an attorney who may never have met the individual,” a police spokesperson said in an unsigned email.

No wonder no one signed this horseshit. Who would want to put their name on such self-interested stupidity?

The NYPD knows lawyers specializing in criminal defense are pretty goddamn good at defending the rights of accused and arrested people. Of course the NYPD doesn’t want anyone qualified to do this important job anywhere near people being questioned, whether they’re juveniles or adults. Pretending its in the best interest of arrestees to get help from people with little to no legal experience works out best for the NYPD and its apparent desire to engage in as much unconstitutional questioning as possible.

It’s not like this is just reform for the sake of reform. It’s the desire to prevent the NYPD from adding to the long list of false confessions and rights violations perpetrated by law enforcement agencies across the nation against minors they’ve arrested. There’s nothing theoretical about the potential harm. There are plenty of real life cases found everywhere in the nation.

Ciaramella highlights just one of them — a case that shows exactly why the NYPD wants children to have access to no one but parents, as well as why this reform effort is sorely needed.

Reason reported in 2021 on the case of Lawrence Montoya, who at the age of 14 falsely confessed to being at the scene of a murder after several hours of being badgered by two Denver police detectives. Montoya’s mother was present for the first part of the interview. She encouraged him to talk and eventually left her son alone in the interrogation room with detectives, allowing them to lean on him until he gave them what they wanted: a flimsy confession constructed with the facts that they had fed to Montoya.

That’s what the NYPD prefers: parents who will likely suggest cooperation is the best route and leave it in the hands of professionals who want to secure confessions and convictions, rather than actually seek justice.

Filed Under: children, civil rights, lawyers, minors, nypd, public defenders, representation

Epic To Pay $520 Million Over Deceptive Practices To Trick Kids

from the before-we-pass-new-laws... dept

Maybe, just maybe, before we rush to pass questionable new laws about “protecting children online,” we should look to make use of the old ones? The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) has been in place for years, and it has problems, but so many companies ignore it. I’ve mentioned in the past how I once walked around a part of CES that had a bunch of startups focused on offering services to kids, and a DC lawyer I was with made sure to ask each one what their COPPA compliance strategy was… and we just got blank stares.

On Monday, video game giant Epic agreed to pay $520 million in two separate fines to the FTC for violating COPPA with some pretty deceptive behavior targeted at kids. First up were your garden variety privacy violations in collecting data on kids under 13 without obtaining parental consent:

- Violated COPPA by Failing to Notify Parents, Obtain Consent: The FTC alleged that Epic was aware that many children were playing Fortnite—as shown through surveys of Fortnite users, the licensing and marketing of Fortnite toys and merchandise, player support and other company communications—and collected personal data from children without first obtaining parents’ verifiable consent. The company also required parents who requested that their children’s personal information be deleted to jump through unreasonable hoops, and sometimes failed to honor such requests.

- Default settings harm children and teens: Epic’s settings enable live on-by-default text and voice communications for users. The FTC alleges that these default settings, along with Epic’s role in matching children and teens with strangers to play Fortnite together, harmed children and teens. Children and teens have been bullied, threatened, harassed, and exposed to dangerous and psychologically traumatizing issues such as suicide while on Fortnite.

As the FTC notes, Epic employees knew this was a problem, but the company didn’t fix things. In fact, when it finally did create an option to turn the voice chat off, “Epic made it difficult for users to find.”

Perhaps more concerning were the deceptive practices.

- Used dark patterns to trick users into making purchases: The company has deployed a variety of dark patterns aimed at getting consumers of all ages to make unintended in-game purchases. Fortnite’s counterintuitive, inconsistent, and confusing button configuration led players to incur unwanted charges based on the press of a single button. For example, players could be charged while attempting to wake the game from sleep mode, while the game was in a loading screen, or by pressing an adjacent button while attempting simply to preview an item. These tactics led to hundreds of millions of dollars in unauthorized charges for consumers.

- Charged account holders without authorization: Children and other users who play Fortnite can purchase in-game content such as cosmetics and battle passes using Fortnite’s V-Bucks. Up until 2018, Epic allowed children to purchase V-Bucks by simply pressing buttons without requiring any parental or card holder action or consent. Some parents complained that their children had racked up hundreds of dollars in charges before they realized Epic had charged their credit card without their consent. The FTC has brought similar claims against companies such as Amazon, Apple, and Google for billing consumers millions of dollars for in-app purchases made by children while playing mobile app games without obtaining their parents’ consent.

- Blocked access to purchased content: The FTC alleged that Epic locked the accounts of customers who disputed unauthorized charges with their credit card companies. Consumers whose accounts have been locked lose access to all the content they have purchased, which can total thousands of dollars. Even when Epic agreed to unlock an account, consumers were warned that they could be banned for life if they disputed any future charges.

I generally dislike the term “dark patterns,” as it’s frequently used to basically just mean “making a service useful in a way that someone else dislikes.” But, uh, yeah, making it way too easy for kids to rack up huge bills on their parents’ credit cards? That seems super sketchy.

For this behavior, Epic will pay $245 million, which the government will use to provide rebates for Fortnite players.

This all seems like the kind of thing that the FTC should be doing, rather than some of the other sillier things it’s been focused on of late. And, also, again, suggests that maybe we don’t need these new, badly drafted laws, but instead should just make sure the FTC is able to better enforce existing laws.

Filed Under: children, coppa, dark patterns, fees, fortnite, ftc, kids, parents, privacy

Companies: epic games

Congress Still Pushing Dangerous ‘Online Safety’ Bill With A Few Flimsy Fixes That Don’t Really Fix Much

from the make-it-stop-already dept

We’ve written a bunch of posts concerning KOSA, the Kids Online Safety Act, which is one of those moral panic kinds of bills that politicians and the media love to get behind, without really understanding what they mean, or the damage they’d do. We’ve covered how it will lead to greater surveillance of children (which doesn’t seem likely to make them safer), how the vague language in the bill will put kids at greater risk, how the “parental tools” provision will be used to harm children, and a variety of other problems with the bill as well. There’s a reason why over 90 different organizations asked Congress not to slip it into a year-end must pass bill.

And while it didn’t make it into the NDAA bill, there are still some efforts to put it in the year end omnibus spending bill. Indeed, the sponsors of the bill quietly released a new version a few days ago that actually does fix some of the most egregious problems of the original. But… it’s still a mess, as TechFreedom’s Ari Cohn explained in a thread on Mastodon.

As his thread notes, there are still concerns about knowing which users are teenagers. The original bill would have effectively mandated age verification, which comes with massive privacy concerns. The new version changes it to cases where a site knows or should know that a user is under 18. But, what constitutes knowledge in that case, and what trips the standard for “should know?” The end result will still be a strong incentive for dodgy age verification, just so sites don’t need to go through the litigation hassle of proving that they didn’t, or shouldn’t, have known the age of their users.

But, the much bigger problem is that the bill still has a “duty of care” component. This was core to the original bill so it’s no surprise that it remains in place. As we’ve discussed for years, the “duty of care” is a “friendly sounding” way of violating the 1st Amendment. In this context, the bill requires sites to magically know if a kid is going to come to some harm from accessing some sort of content on their website. And, given the litigious nature of the US, as soon as any harm comes to anyone under the age of 18, websites will get sued (no matter how loosely they were connected to the actual harm), and they will have to litigate over and over again whether or not they met their “duty of care.”

The end result, most likely, is that websites basically start blocking any kind of controversial content, no matter how legal — and we’re right back to the issue of Congress trying to turn the internet into Disneyland, which is not healthy, takes away both parental and child autonomy, and does not prepare people for the real world.

The new KOSA tries to claim this won’t happen, because it says that nothing in the bill should be “construed to require a covered platform to prevent or preclude any minor from deliberately and independently search for, or specifically requesting, content.” But that won’t make any difference at all, if under the duty of care, the minors find that content, and then can later tie some future harm back to that content. So the real world effect of the law is absolutely going to be to stifle that legal content.

Even worse, lawyers will always stretch things as far as possible to make it possible to sue big pockets, even if they’re very distant from the actual harm. And, as Cohn, notes, the bill is so vaguely worded that the “harm” that can be sued over doesn’t even have to be connected to a minor accessing that content on the site. Rather… under the law as written, it appears that if there are minors on the site and separately, some harm occurs related to some content… KOSA is triggered. So even as the bill is supposedly about protecting children, as written, it can be used if it’s adults who are harmed in some manner, loosely tied to content on the site.

There’s a lot more in Ari’s thread that shows just how dangerous this bill is, even as its backers pretend they’ve fixed all the problems. And yet, Senators Richard Blumenthal and Marsha Blackburn are pleading with their colleagues to put it into the must pass omnibus spending bill.

This is a bill that will give them headlines, allowing them to pretend they’re helping kids, but which actually do tremendous harm to kids, parents, free speech and the internet. Sneaking it into a must pass bill suggests, yet again, that they know the bill is too weak to go through the normal process. The rest of Congress should not allow it to pass in this current state.

Filed Under: children, duty of care, free speech, kosa, marsha blackburn, protect the children, richard blumenthal, section 230

Authentic Brands Group Behind Another Silly Parent, Child Trademark Dispute

from the childish-dispute dept

We’ve talked about Authentic Brands Group here a couple of times and never for good behavior. The company that manages the rights for several living and deceased celebrities is also a notorious trademark troll and enforcer. Most recently we discussed a bizarre trademark opposition brought against Shaqir O’Neal, Shaq’s son, who had the trademark application for Shaqir’s name opposed by ABG… on behalf of his father Shaq.

That was a couple of week ago and, at the time, I had thought it was something of a unique and weird situation, on top of thinking that ABG’s opposition was stupid and dumb. Turns out that kind of stupid and dumb wasn’t as unique as I thought, as now we have a second incident in which this has happened. In this case, Laila Ali, daughter of the late Muhammad Ali, has had her own trademark application for her name opposed by ABG.

A Notice of Opposition was filed by the company that owns Muhammad Ali’s trademark, attempting to stop his daughter Laila Ali from registering her name. Based on information from attorney Josh Gerben, the root of the issues goes all the way back to 2006, when Muhammad Ali sold rights to his trademarks and likeness to Authentic Brands Group (ABG) for $50 million.

According to Josh Gerben, Authentic Brand Group’s filing has three listed complaints in its opposition.

-False Connection: consumers will believe that Laila Ali’s trademark is connected to Muhammad Ali and that any goods sold under her name are licensed by Authentic Brands Group.

-Likelihood of Confusion: the “Laila Ali” and “Muhammad Ali” trademarks are so similar that they will be confused.

-Dilution by Tarnishment: the registration of the “Laila Ali” trademark will harm the reputation of Authentic Brands Group and tarnish its rights in the “Muhammad Ali” trademark.

This bullshit really has to stop. None of ABG’s concerns are legitimate in this instance. The public isn’t going to associate Laila Ali’s trademark to ABG’s any further than acknowledging their father/daughter relationship. The marks in question are also not similar in a form that will confuse the public. It’s her name. “Ali” is also not a terribly unique surname. Does ABG contend that nobody can trademark anything that includes the name “Ali” due to confusion? Because that would be a hell of a claim for the company to make.

And tarnishment? How? Why? Laila Ali isn’t some villain who’s name is somehow going to bring ABG into ill-repute. Frankly, the company is doing just fine in that arena all on its own.

And you really do have to wonder how a counter-culture icon like Muhammad Ali would react to his own daughter being targeted for this sort of thing by a company that rakes in millions of dollars utilizing other people’s names and brands.

Filed Under: children, laila ali, muhammad ali, trademark

Companies: authentic brands