lawyers – Techdirt (original) (raw)

Blame All Around: Lawyers Bicker Over Who Is Responsible For Former Trump Fixer Michael Cohen Submitting AI Hallucinated Case Citations In Court

from the mistakes-were-made dept

As most of you will readily recall, last summer there was quite a lot of attention paid to a case involving a lawyer who had submitted a brief in a personal injury case that had a whole bunch of made up case citations. After this was brought to the attention of the judge, the lawyer on the case admitted that (1) he hadn’t actually done the work, but rather it was another lawyer at his firm who did all the work, and (2) that lawyer had stupidly relied on ChatGPT for his research and hadn’t done the most basic thing to check whether or not the cases were real. This was dumb for oh so many reasons, including that you’re supposed to check case citations against later rulings to make sure the cases you’re citing were still valid.

That whole mess resulted in a $5k fine for the lawyers, as well as a lifetime of embarrassment.

But, on the plus side, hopefully the widespread news coverage of the story would get lawyers to never, ever do that again, right?

Ah, well, silly me. Of course it’s happened again, and this time the culprit is former Trump fixer-turned-Trump accuser (and convicted criminal) lawyer Michael Cohen. There were some shenanigans in his situation over the last few weeks, in which he initially sought early termination of his probation.

Over the last few months, there has been a lot of back and forth on the docket over that motion, and in early December, Cohen switched his own lawyers, as lawyer Danya Perry took over from earlier lawyer David Schwartz. A few days later, Perry filed a letter in support of Cohen’s motion for early termination, and noted in passing that the most recent motion (a week and a half earlier, filed by Schwartz) mentioned some cases that Perry was unable to locate. The following was put in a footnote connected to a paragraph naming a bunch of cases:

Such rulings rarely result in reported decisions. While several cases were cited in the initial Motion filed by different counsel, undersigned counsel was not engaged at that time and must inform the Court that it has been unable to verify those citations.

That footnote appeared to catch Judge Jesse Furman’s attention, and he quickly issued an order to show cause (OSC) to explain all of this:

On November 29, 2023, David M. Schwartz, counsel of record for Defendant Michael Cohen, filed a motion for early termination of supervised release. See ECF No. 88. In the letter brief, Mr. Cohen asserts that, “[a]s recently as 2022, there have been District Court decisions, affirmed by the Second Circuit Court, granting early termination of supervised release.” Id. at 2. He then cites and describes “three such examples”: United States v. Figueroa-Florez, 64 F.4th 223 (2d Cir. 2022); United States v. Ortiz (No. 21-3391), 2022 WL 4424741 (2d Cir. Oct. 11, 2022); and United States v. Amato, 2022 WL 1669877 (2d Cir. May 10, 2022). Id. at 2-3.

As far as the Court can tell, none of these cases exist.1 64 F.4th 223 refers to a page in the middle of a Fourth Circuit decision that has nothing to do with supervised release. See United States v. Drake, 64 F.4th 220 (4th Cir. 2023). 2022 WL 1669877 corresponds to a decision of the Board of Veterans Appeals. See (Title Redacted by Agency), Bd. Vet. App. A22004268, 2022 WL 1669877 (Mar. 11, 2022). 2022 WL 4424741 appears to correspond to nothing at all. Moreover, the Court contacted the Clerk of the Court for the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, who found no record of any of the three decisions and reported that the one listed docket number (for Ortiz) is not a valid docket number.

In light of the foregoing, Mr. Schwartz shall, no later than December 19, 2023, provide copies of the three cited decisions to the Court. If he is unable to do so, Mr. Schwartz shall, by the same date, show cause in writing why he should not be sanctioned pursuant to (1) Rule 11(b)(2) & (c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, (2) 28 U.S.C. § 1927, and (3) the inherent power of the Court for citing non-existent cases to the Court. See, e.g., Mata v. Avianca, Inc., No. 22-CV-1461 (PKC), 2023 WL 4114965 (S.D.N.Y. June 22, 2023). Any such submission shall take the form of a sworn declaration and shall provide, among other things, a thorough explanation of how the motion came to cite cases that do not exist and what role, if any, Mr. Cohen played in drafting or reviewing the motion before it was filed.

There’s so much craziness to come that I’ll just breezily mention how insane it is that it was Cohen’s own (new) lawyer, and then the judge, who started exploring this and not the DOJ, but… let’s move on.

At this point, there was plenty of speculation that we had another ChatGPT lawyer situation on our hands, but I held off reporting on this until we got more details. And, as each new detail came out, things got dumber.

A few days later there was another order from Judge Furman (who, in the past, has shown that he has little patience for lawyers playing games), saying that Cohen’s previous lawyer, David Schwartz, had not just lawyered up but had requested that his response to the OSC be sealed, noting that it might implicate attorney-client privilege:

On December 15, 2023, Schwartz — through counsel of his own — filed a response to the Court’s Order to Show Cause accompanied by a letter-motion to seal his response. In the letter-motion, counsel opine that Schwartz’s response to the Order to Show Cause “implicates the confidentiality of the attorney-client privilege,” but that, “under the unique circumstances present here,” the New York Rules of Professional Conduct permit — indeed, require — disclosure of those communications to the Court. The letter-motion requests that Schwartz’s submission be maintained under seal “until” the Court resolves “whether Mr. Schwartz can reveal the information stated in his affirmation without violating the attorney-client privilege.”

This resulted in even more speculation, as it certainly seemed to suggest that Cohen had sent him the made up case citations, and thus revealing the details of how he got them would disclose confidential attorney-client communications.

Judge Furman let Schwartz seal “on a temporary basis.” On December 28th, the sealed filing was made, and on the 29th Judge Furman said that Cohen had granted to unseal the response.

There are a few different things in the unsealed filings worth highlighting. First, there’s a declaration from Cohen’s former lawyer David Schwartz, in which hs basically throws Cohen’s new lawyer, Danya Perry under the bus:

In preparing the current submission, on November 12, 2023, I sent Mr. Cohen a draft of my proposed letter to the Court. Notably, my original draft letter did not cite any cases. It was never my intention to cite any cases as I felt that the application was strong enough, based on all the facts and circumstances. The original draft letter sent to Mr. Cohen was dated May 30, 2023 (Exhibit B)

It was apparent and clear to me that E. Danya Perry, counsel for Mr. Cohen in prior proceedings1 , reviewed my original draft letter, dated May 30, 2023. Ms. Perry, a renowned and skilled trial lawyer, is the Founding Partner at Perry Law. She is a recognized white collar criminal defense attorney and commercial litigator who has represented various corporations and individuals in high-profile matters. Notably, she is a former Assistant United States Attorney in the Southern District and served as Deputy Chief of the Criminal Division.

On November 12, 2023, Michael Cohen sent me a redlined draft of the letter, ostensibly prepared by Ms. Perry. It contained comments and, specifically, a suggestion that “you should have a few in-district court cases where judge granted early termination.” The comments were labeled “DP”, which I believed were attributed to Danya Perry. (Exhibit C)

In Exhibit “c” we see the suggestions:

Schwartz also says that Cohen says these edits were “sent to me from Danya.”

A few days later, after Schwartz made the changes Perry had suggested, but had not added any citations, he received emails from Cohen with citations:

On November 25, 2023, my office received three emails from Mr. Cohen with the three cases in question plus summaries of the cases. (Exhibit E) As Mr. Cohen had previously forwarded Ms. Perry’s edits of the draft letter, and as Ms. Peny had suggested that case law be added to the letter, I believed that Mr. Cohen was now sending me cases that had been found by Ms. Perry. Prior to receiving these emails, Mr. Cohen communicated to me that cases would be provided by Ms. Perry.

Admittedly, because of Ms. Perry’s reputation, I relied on her skills as an attorney and as someone who had been working with me in preparing this submission; as a result, I did not independently review the cases.

I failed to review what I thought was the research of another attorney.

I never contemplated that the cases cited were “non-existent.”

In the exhibits it shows the emails from Cohen, which are actually forward from what appears to be Michael Cohen’s wife’s email account. There are three emails, each with a different citations. Here is just the first one:

Schwartz then notes that after the OSC was issued, he reached out to Perry’s law firm, telling them he thought Perry had found the citations, and was told that Cohen had found them via Google:

After I was served with the Show Cause Order on December 12, 2023, I spoke with Lilian M. Timmerman, a Partner at Perry Law. After I explained to her that I believed that her office had “found” the cases in question, she told me that Mr. Cohen had admitted to them that he had found the cases on Google.

If I had believed that Mr. Cohen had found these cases, I would have researched them. It was my belief, however, that Mr. Cohen had sent me cases found by Ms. Perry.

Perry then filed a response, effectively saying “well, wasn’t this all a big misunderstanding, ha ha ha” while noting that Cohen had no responsibility to investigate the reality of the case citations he had found — but also throwing Schwartz under the bus himself, noting it really should have been his responsibility to check the cases:

Mr. Schwartz’s recollection of the events is largely consistent with Mr. Cohen’s. While this response provides a few clarifications, we believe the Court could well find them to be immaterial. To summarize: Mr. Cohen provided Mr. Schwartz with citations (and case summaries) he had found online and believed to be real. Mr. Schwartz added them to the motion but failed to check those citations or summaries. As a result, Mr. Schwartz mistakenly filed a motion with three citations that—unbeknownst to either Mr. Schwartz or Mr. Cohen at the time—referred to nonexistent cases. Upon later appearing in the case and reviewing the previously-filed motion, I discovered the problem and, in Mr. Cohen’s reply letter supporting that motion, I alerted the Court to likely issues with Mr. Schwartz’s citations and provided (real) replacement citations supporting the very same proposition. ECF No. 95 at 3. To be clear, Mr. Cohen did not know that the cases he identified were not real and, unlike his attorney, had no obligation to confirm as much. While there has been no implication to the contrary, it must be emphasized that Mr. Cohen did not engage in any misconduct.

Hilariously, in a footnote, Perry notes that Cohen also sent an actual real citation that was relevant… but that Schwartz didn’t include that one in the filing.

And here, finally, we find out where Cohen convinced an AI to dream up these results. It wasn’t ChatGPT like that earlier case, but rather in Google’s Bard, which has recently expanded to provide AI-generated responses to search terms directly in search:

The invalid citations at issue—and many others that Mr. Cohen found but were not used in the motion—were produced by Google Bard, which Mr. Cohen misunderstood to be a supercharged search engine, not a generative AI service like Chat-GPT. Cohen Decl. ¶ 20. Mr. Cohen had used Google Bard to successfully identify accurate information in other contexts before and did not appreciate its unreliability as a tool for legal research. Id. Like most lay clients, Mr. Cohen does not have access to Westlaw or other standard legal research tools to verify any citations he finds online. Id. Instead, he trusted his attorney to verify them on his behalf. Id.

Mr. Cohen is not a practicing attorney and has no concept of the risks of using AI services for legal research (Cohen Decl. ¶ 20)—nor does he have an ethical obligation to verify the accuracy of his research. Mr. Schwartz, conversely, did have an obligation to verify the legal representations being made in a motion he filed. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 11; Rules of Professional Conduct (22 NYCRR 1200.0) Rule 1.1. Unfortunately, Mr. Schwartz did not fulfill that obligation—as he was quick to admit, to his credit. Schwartz Decl. ¶¶ 21–22.

Mr. Cohen sent Mr. Schwartz and his paralegal the citations and summaries on November 25. Cohen Decl. ¶ 15; Schwartz Ex. E. Mr. Schwartz and his team then added the citations and descriptions to the motion, went through several additional rounds of revisions (in which Mr. Schwartz was actively involved), and then filed the motion at Mr. Schwartz’s direction. See Cohen Decl. ¶ 21. As Mr. Cohen’s attorney and fiduciary, Mr. Schwartz had final sign-off on the submission and its content. Cohen Decl. ¶ 11. Unbeknownst to Mr. Cohen, Mr. Schwartz signed off on the motion without having ever checked the citations it contained. Cohen Decl. ¶ 22; Schwartz Decl. ¶¶ 21–22. In summary, Mr. Schwartz’s inclusion of the invalid citations was a mistake driven by sloppiness, not malicious intent.

Perry then also further drives the knife into Schwartz:

Also unbeknownst to Mr. Cohen, this is not the first instance in which Mr. Schwartz has been less than meticulous about the accuracy of his citations. In his May 2023 letter to the Court— long before he could have believed that I had any background involvement—Mr. Schwartz (somewhat oddly) offered characterizations about the Seventh Circuit’s approach to terminating supervised release claiming his account was “per a published opinion of the 7th circuit dealing with supervised release.” ECF No. 84 at 2. In reality, Mr. Schwartz simply cited a blogpost—not a “published opinion” at all—which itself is thinly sourced and appears to overstate the rigidity of Seventh Circuit law. For example, the motion and blogpost both claim that “five purposes of supervision” are used to indicate satisfactory completion of supervised release’s “decompression stage” but the undersigned has been unable to locate a discrete case substantiating that rigid framework in which the five purposes become “factors that mark [the completion of] this decompression state and satisfy that requirement [of completing a decompression state postprison].” Id. (citing PCR Consultants, “Federal Supervised Release is not Punishment,” https://pcrconsultants.com/federal-supervised-release-is-not-punishment/).

Further, even a quick read of the non-existent cases at issue here should have raised an eyebrow. For example, one of the citations purported to have a 2021 docket number, yet also purported to describe a matter in which a defendant had served a 120-month sentence before being placed on supervised release, the early termination of which had purportedly been affirmed by the Second Circuit— a chronological impossibility on its face. Had Mr. Schwartz skimmed that citation before submitting it to the Court, he might have noticed something awry.

That filing also includes Cohen’s own declaration which itself has some fun tidbits:

I must rely on my attorneys in this matter because I was disbarred nearly five years ago…

The declaration also serves to throw Schwartz under the bus, saying that he “trusted that Mr. Schwartz would pursue and incorporate my ideas to the extent he thought they were appropriate…” but that “as my fiduciary, Mr. Schwartz had final sign-off on each of those submissions.”

He details how he found those case citations:

Specifically, the citations and descriptions came from Google Bard. As a non-lawyer, I have not kept up with emerging trends (and related risks) in legal technology and did not realize that Google Bard was a generative text service that, like Chat-GPT, could show citations and descriptions that looked real but actually were not. Instead, I understood it to be a super-charged search engine and had used it in other contexts to (successfully) find accurate information online. I did not know that Google Bard could generate non-existent cases, nor did I have access to Westlaw or other standard resources for confirming the details of cases. Instead, I trusted Mr. Schwartz and his team to vet my suggested additions before incorporating them.

The thing is… this is bullshit. For federal cases, you don’t actually need Westlaw to confirm their existence. But… whatever.

Schwartz, realizing he was being thrown under the bus (after he threw Perry under the bus) tried to get in the last word as well:

I work in a law office in which Westlaw and Lexis/Nexis are readily available. I would never, and certainly did not, use any type of Artificial Intelligence tool to draft my motion papers on behalf of Mr. Cohen (nor would I do so for any other client). In fact, after reading Mr. Cohen’s declaration, I found out for the first time that he used Google Bard to find those cases. I can assure the Court that I had never heard of this program and our attorneys only use Westlaw or Lexis/Nexis for their legal research.

I realize I made a serious error when I trust Mr. Cohen to be the conduit between myself and his other attorney, Ms. Perry.

Then he goes on to explain why he believed the citations came from Perry, pointing out that Cohen had given Perry a copy of Schwartz’s original draft, and sent back comments and a redline from her.

And, the key point, Schwartz now claims that Cohen told him over the phone that Perry would provide citations:

After receiving the redline changes from Ms. Perry, through Mr. Cohen, I spoke with Mr. Cohen via telephone, as I did frequently. On those calls, he reiterated to me that Ms. Perry “would be” providing the cases. I was in error in failing to communicate with Ms. Perry to confirm this.

In other words, Schwartz is arguing that his real mistake was not talking directly to Perry, but letting Cohen be his main communication source. He also later claims that Cohen screwed up other communications as well, including telling Perry not to alert Schwartz about the false citations, saying that he (Cohen) would tell Schwartz himself, but did not.

I understand that when asked by my attorneys why she failed to alert me about the fictitious citations before notifying the Court, Ms. Perry told them that she was going to contact me, but Mr. Cohen wanted to notify me himself. Ms. Perry apparently relied on Mr. Cohen to do that. But Mr. Cohen did not notify me about the citation issue. If Ms. Perry had notified me, instead of using Mr. Cohen as a conduit, I would certainly have withdrawn these citations immediately.

In other words “many mistakes were made, and there’s a lot of blame to go around here.”

Also, friendship apparently blurs responsibilities?

Unfortunately, it appears to me that when Mr. Cohen submitted cases to me, he was submitting them to his friend of many years and neglected to focus on the fact that I am an officer of the court. The lines here were clearly blurred between friendship and attorney/client.

I mean, it seems like that’s accurate representation of what happened, but still, if you’re a lawyer filing documents with a court, you still kinda gotta do the underlying work.

Filed Under: ai, case citations, danya perry, david schwartz, google bard, hallucinations, jesse furman, lawyers, michael cohen

Companies: google

Will Clients Now Just Blame All Bad Lawyering On ChatGPT?

from the the-ai-made-me-do-it dept

We all remember the infamous case from earlier this year, in which lawyer Steven Schwartz had to admit that he had used ChatGPT to help construct a brief (which was then signed by another lawyer, a partner at his firm), and that neither lawyer bothered to check whether or not the citations were made up (they were). Schwartz had to pay $5k in sanctions, and readily admits that the punishment is that his reputation is now “the lawyer who used ChatGPT”

That story went so viral that you would hope it would mean that most lawyers heard about it, and understood not to do that kinda thing. However, there was recently another story suggesting a similar situation. LAist has the details of an infamous eviction lawyer who was sanctioned for fabricated cases in a filing, which many people think were probably AI generated.

At first glance, the filing from April looks credible. It’s properly formatted. Block’s signature at the bottom lends a stamp of authority. Case citations are provided to bolster Block’s argument for why the tenant should be evicted.

But when L.A. Superior Court Judge Ian Fusselman took a closer look, he spotted a major problem. Two of the cases cited in the brief were not real. Others had nothing to do with eviction law, the judge said.

“This was an entire body of law that was fabricated,” Fusselman said during the sanction hearing. “It’s difficult to understand how that happened.”

Apparently a bunch of people believe that it was another Schwartz situation with ChatGPT making up cases.

But, an even more “lawyer uses GPT” story is shaping up in a different case. Former Fugees star Pras Michel was convicted on 10 felony counts earlier this year, but he’s made a motion for a new trial, arguing in part, that his previous lawyer used AI to write the closing arguments in the case. There are many arguments in the motion regarding claimed problems with the trial, and the ineffective counsel arguments include a bunch of things as well.

But the AI claims… well… stand out. The argument is not just that Michel’s lawyers used AI to write the closing arguments, but that they were investors in the company that made the AI, which is why they used it:

It is now apparent that the reason Kenner decided to experiment at Michel’s trial with a never-before-used AI program to write the closing argument is because he and Israely appear to have had an undisclosed financial interest in the program, and they wanted to use Michel’s trial as a test case to promote the program and their financial interests. Indeed, the press release the AI company issued after the trial that quotes Kenner praising the AI program states that the company launched the program “with technology partner CaseFile Connect.” Zeidenberg Decl. ¶ 7 & Ex. C. The CaseFile Connect website does not identify its owners, but it lists its principal office address as 16633 Ventura Blvd., Suite 735, which the California Bar website indicates is the office address for Kenner’s law firm. Id., Ex. F. Open sources further indicate that the third office address CaseFile Connect’s website provides is associated with Kenner’s co-counsel and friend, Israely. Id., Ex. G. The reason they used the experimental program during Michel’s trial and then boasted about it in a press release is now clear: They wanted to promote the AI program because they appear to have had a financial interest in it. They did this even though this experiment adversely affect Michel’s defense at trial, creating an extraordinary conflict of interest.

To be honest, there’s not much more in the motion regarding the AI, how it was actually used, or if it made bad arguments. There is a lot more detail regarding the judge telling Michel that it was possible his lawyer had conflict-of-interest issues, and how those needed to be resolved.

But this did make me wonder if we’re going to see more claims like this going forward, whenever someone loses a case and wants to argue ineffective assistance of counsel. Will they just throw in some random “and he used AI!” to make it sound more compelling?

Filed Under: ai, ai lawyers, chatgpt, david kenner, dennis block, lawyers, pras michel

Companies: casefile connect

Twitter Sues The Law Firm That Made Elon Live Up To The Contract He Signed To Buy Twitter

from the penny-pinching dept

Elon Musk’s Twitter is apparently really hard up for cash. In addition to not paying rent or other important bills, it is now trying to claw back bills that were paid just prior to Elon getting the keys to Twitter. As you may have heard, last week, Twitter sued Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, well known powerhouse law firm for dealing with mergers and acquisitions, which very successfully represented Twitter in court to force Elon to actually complete the deal he had signed, which he then tried to get out of.

The full complaint is massive (though the actual complaint is just 32 pages, and then there are over 100 pages of exhibits) but can be summarized as Elon claiming that right before he completed the purchase, Twitter’s top execs signed off on sending tens of millions of dollars to Wachtell for… successfully getting Elon to buy the company. Twitter is now basically claiming that the company overpaid the lawyers (who are famously expensive) in breach of fiduciary duty.

In the days and hours leading up to the closing of the sale of Twitter on October 27, 2022, Wachtell and its litigation department led by Bill Savitt were at the center of a spending spree by Twitter’s departing executives who ran up the tab at Twitter by, among other things, facilitating the improper payment of substantial gifts to preferred law firms like Wachtell on top of the firms full hourly billings by designating tens of millions of dollars in hand outs to the firms as success or project fees. Despite having previously agreed to work on an hourly fee basis and subsequently charging millions in hourly fees under that arrangement, Wachtell disregarded both California law and its ethical and fiduciary duties in the final days of its four-month Twitter engagement to improperly solicit an unspecified clearly gargantuan success fee, as part of a 90milliontotalfeethatalsopurportedtosatisfyWachtell’searlierinvoicesthattotaled90 million total fee that also purported to satisfy Wachtell’s earlier invoices that totaled 90milliontotalfeethatalsopurportedtosatisfyWachtell’searlierinvoicesthattotaled 17,943,567.49. The 90millionfeecollectedfromTwitterforafewmonthsofworkonasinglematterrepresentednearly1090 million fee collected from Twitter for a few months of work on a single matter represented nearly 10% of Wachtell’s gross revenue in 2022, and over 90millionfeecollectedfromTwitterforafewmonthsofworkonasinglematterrepresentednearly101 million per Wachtell partner.

Mere hours before the October 27 closing, Twitter’s Chief Legal Officer Vijaya Gadde signed anew letter agreement that Wachtell had drafted (the Closing Day Letter Agreement), which purported to award Wachtell the success fee and required payment of the balance of the $90 million total fee on incredibly accelerated terms prior to closing. Fully aware that nobody with an economic interest in Twitter’s financial well-being was minding the store, Wachtell arranged to effectively line its pockets with funds from the company cash register while the keys were being handed over to the Musk Parties. By this action, Twitter’s successor-in-interest, X Corp., seeks to void the unconscionable Closing Day Letter Agreement and disgorge the excess fees paid to Wachtell under the unenforceable contract and in violation of Wachtell’s, and Twitter’s then- leadership’s, fiduciary duties and California law.

No doubt, there are some bits here that seem fishy. A massive payout right before ownership changes hands is certainly going to raise some eyebrows. However, there is at least some evidence that this is just how Wachtell works. For much of the last decade, there was a lawsuit between Carl Icahn and Wachtell regarding the firm’s fees in trying to help CVR resist a takeover from Icahn. And, as securities and corporate law expert Ann Lipton pointed out on social media, this lawsuit resulted in the revelation of a Wachtell engagement letter, in which the company makes clear that if it succeeds, it expects a negotiated success fee upon reaching “achievement of major milestones.”

As that notes:

Our expectation is that upon conclusion of the matter or from time to time upon achievement of major milestones, our final compensation will be agreed with you, mutually and reasonably, and will reflect the fair value of what we have accomplished for the company.

That said, the complaint here suggests that this kind of arrangement was not in place with Twitter, and that it was basically a last minute raiding of the bank account. The complaint notes that while there was some discussion of a potential success fee, the eventual engagement letter was just for hourly fees, and does not mention a success fee.

That said, there are other things in the complaint where I’d argue that Twitter’s claims are just laughably false, so I’m not sure how much to trust the rest of it. For example:

Beginning in early May 2022, the Musk Parties sought information from Twitter concerning the prevalence of spam bot or fake accounts on the platform, information the Musk Parties noted they were entitled to under the Merger Agreement. Twitter resisted providing the information the Musk Parties requested. The dispute played out publicly with each round of letters filed as part of regulatory disclosures. On June 6, 2022, counsel for the Musk Parties sent a letter to Gadde and Twitter reiterating the information request and indicating that Twitter’s efforts to thwart the Musk Parties information rights was a clear material breach of Twitter’s obligations under the merger agreement and Mr. Musk reserves all rights resulting therefrom, including his right not to consummate the transaction and his right to terminate the merger agreement.

I mean, sure that’s what Musk claimed, but, as (1) was obvious at the time and (2) came out much more clearly during the lawsuit, this was all bullshit. It was a pretextual excuse for Musk to pretend he could get out of the deal when the terms of the deal did not allow that. Indeed, as became clear, Twitter had, in fact, handed over the necessary information to Musk, which only covered information necessary to close the deal (and even there, the company went above and beyond, providing him more information regarding spam, which Musk continued to misrepresent publicly).

So, forgive me for not necessarily believing the version of events described here.

There are some other eyebrow raising claims in the complaint, including the lack of details in the hourly timesheets that Wachtell submitted, but it feels kinda like this is Wachtell’s standard practices, when it is billing hourly. There is also a claim that Wachtell billed Twitter for work on other matters, unrelated to the Twitter case for other clients. That seems… not great?

But the rest of the discussion does look like Wachtell negotiating a success fee from the existing Twitter executives and board. And, for all the talk of fiduciary duties, their fiduciary duty was to get Musk to pay the ridiculous sum he agreed to pay in the first place, and Wachtell certainly played a role in making that happen. Therefore, the success fee doesn’t seem that crazy. Basically, Wachtell just helped Twitter’s shareholders (for whom Twitter execs were working for at the time) get 44billion.Assuch,a44 billion. As such, a 44billion.Assuch,a90 million fee doesn’t seem so crazy.

Now, in general, I would say it is… kinda weird… to see a law firm not detail out all of the fees, and then negotiate a multi-million dollar fee in what seems like a somewhat informal manner. But, as a counterpoint:

It seems that, sometimes, the ultra wealthy make informal agreements for staggering amounts of money.

Filed Under: elon musk, fees, lawyers, success fee

Companies: twitter, wachtell

Madison Square Garden’s Facial Recognition-Enabled Bans Now Being Targeted By Legislators, State AG

from the yet-another-problematic-use-of-the-tech dept

Late last year, it was revealed that MSG Entertainment (the owner of several New York entertainment venues, including the titular Madison Square Garden) was using its facial recognition tech to, in essence, blacklist its owner’s enemies.

Those targeted included lawyers working for firms currently engaged in litigation against MSG Entertainment. Owner James Dolan, through his company’s PR wing, stated these bans were meant to prevent adversarial litigants from performing ad hoc discovery by snooping around arenas under the auspices of event attendance.

That might have made sense if it only targeted lawyers actually involved in this litigation. But these blanket bans appeared to deny access to any lawyer employed by these firms, something that resulted in a woman being unable to attend a Rockettes performance with her daughter and her Girl Scout troop, and another lawyer being ejected from a Knicks game.

These facial recognition-assisted bans immediately became the subject of new litigation against MSG Entertainment. Some litigants were able to secure a temporary injunction by reaching deep into the past to invoke a 1941 law enacted to prevent entertainment venues from banning entertainment critics from attending events.

The restraining orders were of limited utility, though. Some affected lawyers still found themselves prevented from entering despite carrying copies of the injunction with them. And the law itself has a pretty significant loophole: it does not cover sporting events, which are a major part of MSG Entertainment’s offerings.

While possibly legal (given that private companies can refuse service to anyone [for the most part]), it was also stupid. It looked more vindictive than useful, with owner James Dolan punishing anyone who had the temerity to be employed by law firms that dared to sue his company. It’s robber baron type stuff and it never plays well anywhere, which you’d think someone involved in the entertainment business would have realized.

Now, the government is coming for Dolan and his facial recognition tech-based bans. As Jon Brodkin reports for Ars Technica, the state attorney general’s office is starting to ask some serious questions.

[AG Letitia] James’ office sent a letter Tuesday to MSG Entertainment, noting reports that it “used facial recognition software to forbid all lawyers in all law firms representing clients engaged in any litigation against the Company from entering the Company’s venues in New York, including the use of any season tickets.”

“We write to raise concerns that the Policy may violate the New York Civil Rights Law and other city, state, and federal laws prohibiting discrimination and retaliation for engaging in protected activity,” Assistant AG Kyle Rapiñan of the Civil Rights Bureau wrote in the letter. “Such practices certainly run counter to the spirit and purpose of such laws, and laws promoting equal access to the courts: forbidding entry to lawyers representing clients who have engaged in litigation against the Company may dissuade such lawyers from taking on legitimate cases, including sexual harassment or employment discrimination claims.”

The AG’s office also expressed its concerns about facial recognition tech in general, noting it’s often “plagued with biases and false positives.” It’s a legitimate concern, but perhaps AG James should cc the NYPD, which has been using this “plagued with bias” tech for more than a decade.

Dolan/MSG’s plan to keep booting lawyers from venues is now facing another potential obstacle. City legislators are prepping an amendment that would pretty much force MSG to end this practice.

“New Yorkers are outraged by Madison Square Garden booting fans from their venue simply because they’re perceived as corporate enemies of James Dolan,” the bill’s sponsor, state Sen. Brad Hoylman-Sigal, told the Daily News.

“This is a straightforward, simple fix to the New York State civil rights law that would hopefully prevent fans from being denied entry simply because they work for a law firm that may have a client in litigation against Madison Square Garden Entertainment,” he added.

It is a simple fix. The bill would take the existing 1941 law — the one forbidding entertainment venues from banning critics — and close the sporting event loophole. That would pretty much cover everything hosted by MSG, which would make Dolan’s ban plan unenforceable.

Of course, none of this had to happen. If Dolan and MSG were having problems with adversarial lawyers snooping around their venues, they could bring this to the attention of the courts handling these cases. A blanket ban of entire law firms did little more than anger the sort of people you generally don’t want to piss off when there’s litigation afoot: lawyers. What looked like a cheap and punitive win now looks like a PR black eye coupled with a brand new litigation headache.

Filed Under: facial recognition, james dolan, lawsuits, lawyers, letitia james, new york

Companies: msg entertainment

Lawyers Blocked From Entering Madison Square Garden By Vindictive Owner Use 1941 Law To Bypass Bullshit Ban

from the if-there's-one-thing-lawyers-know,-it's-laws dept

There are lots of ways facial recognition tech can be misused. Since it’s far from infallible, the most common misuse of the tech is accepting matches as statements of fact. What should be considered, at best, an investigative lead, has instead been used to wrongly arrest people for crimes they didn’t commit.

The private sector has access to the same tech. But it’s not subject to even the minimal guidelines applied to government deployment. Businesses have the right to refuse service to anyone, but even that blanket statement has exceptions.

Even if you have the leeway to ban people from your premises, the question remains whether you should do so, especially when the bans appear to be vindictive. Earlier this month, some New York City lawyers reported they were being blocked from entering venues operated by MSG Entertainment, the company that owns Madison Square Garden and other city entertainment venues. These bans — enforced by MSG’s use of facial recognition tech — prevented a mother from joining her daughter and her Girl Scout troop during a visit to Radio City Music Hall. Another lawyer was booted from a Knicks game at the Garden after being flagged by MSG’s tech.

This entirely new problem could be traced back to MSG’s chief executive, James L. Dolan. Last summer, he instituted a ban affecting lawyers working for firms engaged in litigation against MSG Entertainment. The ban was supposed to prevent adversarial lawyers from engaging in freelance discovery while attending events. The problem was the ban targeted all lawyers at these firms, rather than just those actually engaging in litigation.

These blanket bans are generating even more litigation (which will, of course, generate more bans, etc.). But some enterprising lawyers working for firms shortsightedly targeted by MSG’s bans have found a way to get back into these venues. Unsurprisingly, it involves a law — and a rather old law at that, as Kashmir Hill reports for the New York Times.

In the late 1930s, Leonard Lyons, a columnist for the New York Post, was barred from “30-odd theaters,” he said in a column, because he had written nasty things about the Shubert family, including a story about the theater owners charging a playwright $7 to hang curtains in his dressing room, which the playwright spitefully paid in pennies.

Mr. Lyons, who had a law degree himself according to his son Jeffrey, consulted an A.C.L.U. lawyer, Morris Ernst, who informed him that “the Woollcott decision was binding,” as he later wrote in his column, The Lyons Den. “The law’s against you,” Mr. Ernst said, “unless you change the law.”

And so Mr. Ernst drafted a law guaranteeing anyone over the age of 21 admittance to “legitimate theaters, burlesque theaters, music halls, opera houses, concert halls and circuses,” with exceptions for abusive or offensive behavior, and he and Mr. Lyons persuaded a state representative from Manhattan to push it forward. It was signed into law in April 1941 despite Lee Shubert sending a letter to the governor objecting that it was a “one man” bill, intended to protect Mr. Lyons’s ability “to find some additional material which can form the basis of further attacks on Messrs. Shubert.”

The law stopped entertainment venues from blocking access to critics. The law is still on the books and lawyers affected by the MSG Entertainment ban utilized the 80-year-old law to secure an injunction forbidding these venues from denying them access. The venues can still refuse to sell blacklisted lawyers tickets, but they can’t prevent them from entering if they hold valid tickets. Of course, having an injunction in hand doesn’t mean venue operators or their security teams won’t immediately violate the court order.

After a preliminary injunction was granted in November, Mr. Noren tried to go to a Wizkid concert at Madison Square Garden. Despite bringing a printout of the judge’s order granting the preliminary injunction, he was stopped and turned away by security officials, an encounter he recorded on his smartphone.

You can’t litigate in a venue vestibule, so that means Dolan and his company can continue to score unearned wins. And the application of the law doesn’t mean automatic entry to every event hosted by MSG Entertainment. A carve out for sporting events in the 1941 law means the previously banned lawyers can attend concerts and shows, but can still be legally refused entry to Knicks games.

This whole debacle highlights yet another problematic aspect of facial recognition tech: it can be used to engage in new forms of discrimination, allowing business owners to effectively ban people they just don’t like, whether they’re lawyers working for adversarial law firms, or people who just don’t fit the preferred demographic the venue/store/etc. wishes to attract. Enacting petty bans because tech makes it that much easier to enforce is just going to invite litigation, legislation, and negative press — something no company should welcome or encourage if it wants to remain solvent.

Filed Under: facial recognition, james dolan, lawyers, new york, theaters

Companies: msg, msg entertainment

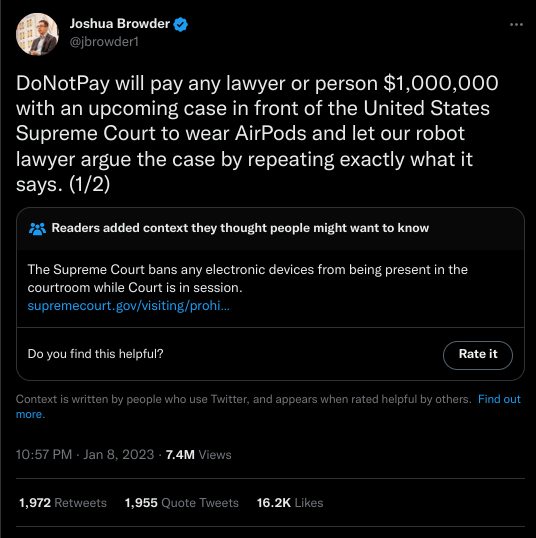

AI Creator Offers $1 Million He’ll Never Have To Pay To Anyone Willing To Let His Lawbot Argue Their Supreme Court Case

from the bluff-that-can-never-get-called dept

Josh Browder — the creator of the DoNotPay AI lawbot that helped users dodge $4 million in parking tickets — thinks his AI is ready to head to the big leagues.

Up until now, the bot’s progress (and its creator’s claims) have been incremental. Browder created a version of the bot to assist people in crafting asylum applications. Immigration law is deliberately complex and people seeking asylum generally don’t have access to skilled lawyers, so anything that helps even the odds is welcome.

More recently, Browder announced his bot was going “live,” so to speak. A person will be using Browder’s lawyer bot in municipal court, allowing the AI to process judge’s statements/questions and provide suitable responses/rebuttals for the guinea pig accused of traffic infractions.

This case still hasn’t happened, so there’s no data on how well it performs when faced with unpredictable human beings, rather than simply navigating the paperwork involved in challenging parking tickets or filling out asylum applications. This lack of real world experience isn’t discouraging Browder from claiming his bot is capable of replacing experienced lawyers with extensive pedigrees.

Over last weekend, Browder decided to put his money where his mouth is:

There’s some money at stake now. Browder’s tweet reads:

DoNotPay will pay any lawyer or person $1,000,000 with an upcoming case in front of the United States Supreme Court to wear AirPods and let our robot lawyer argue the case by repeating exactly what it says.

Sounds like quite the bet! Except it really isn’t. First off, no lawyer is going to willingly give up an opportunity to argue in front of the Supreme Court, something that tends to look really good on the C.V., even if they end up taking a loss.

But, more importantly, this simply can’t happen, no matter if Browder can find any lawyer or Supreme Court supplicant willing to turn over their case to his AI. As many people pointed out in response to Browder’s bravado, AirPods aren’t allowed inside the court. The list of items that can’t be brought into the Supreme Court starts with the items necessary to allow a law-focused chatbot to argue a case.

The following items are strictly prohibited in the Courtroom while Court is in session:

- Electronic devices of any kind (laptops, cameras, video recorders, cell phones, tablets, smart watches, etc.)

This leads a list that contains food, beverages, books, stroller, political buttons/attire, and “inappropriate clothing.”

That makes use of Browder’s bot an impossibility. And that means he can tweet out offers of millions of dollars with the assurance he’ll never find any takers.

But even if people could bring electronic devices into the Supreme Court, they probably still shouldn’t take Browder up on his offer. The bot has no track record in court. It’s being test run at the lowest level of the court system — traffic court — at some point in the near future. No one knows how that case is going to go. And, given the low stakes, it will be almost impossible to tell if the bot contributed to the ensuing win/loss.

Jumping from traffic court to the top court in the land is foolhardy, even for actual living lawyers. Browder’s bot may have more machine learning, but it’s unlikely it’s ready for prime time when things larger than traffic tickets (like people’s lives and freedoms) are on the line.

Filed Under: ai, josh browder, lawyers, marketing stunts, supreme court

Companies: donotpay

NYPD Says Kids Don’t Need Lawyers While Fighting Reforms Targeting Interrogations Of Minors

from the all-lawyers-do-is-make-us-respect-rights! dept

Leave it to the NYPD to suggest some people’s rights just don’t matter. The NYPD has resisted pretty much every reform effort shoved in its general direction and this one — which would affect questioning of juvenile detainees — is being resisted as well. (“Stop resisting!” only works in one direction, unfortunately.)

Here’s C.J. Ciaramella with more details for Reason:

The City recently reported that a coalition of public defenders, juvenile justice organizations, and other groups are pushing to pass a bill in the next session of the New York Legislature that would require minors speak with a lawyer before they waive their Miranda rights and talk to police.

If such a bill passed, New York would join several other states that have tightened rules for juvenile interrogations in recent years. Both Maryland and Washington passed laws requiring attorney consultations for minors before interrogations. Last year, Illinois became the first state in the U.S. to ban police from lying to minors during interrogations. Oregon followed suit shortly after.

It’s a simple reform: one that ensures minors receive the same constitutional protections adults do when detained by police. There’s no reason they shouldn’t have these protections. While the rights of minors can sometimes be slightly diminished to ensure things like school safety, their rights when arrested by police officers remain exactly the same as every other American.

All this would do is force the NYPD to give juveniles access to lawyers during questioning — the same demand that can be made by anyone under arrest. The NYPD ain’t having it, though. And, as Ciaramella points out, the statement it gave The City suggests it thinks children should be underserved when arrested, unable to fully utilize their constitutional rights.

“Parents and guardians are in the best position to make decisions for their children, and this bill, while well-intentioned, supplants the judgment of parents and guardians with an attorney who may never have met the individual,” a police spokesperson said in an unsigned email.

No wonder no one signed this horseshit. Who would want to put their name on such self-interested stupidity?

The NYPD knows lawyers specializing in criminal defense are pretty goddamn good at defending the rights of accused and arrested people. Of course the NYPD doesn’t want anyone qualified to do this important job anywhere near people being questioned, whether they’re juveniles or adults. Pretending its in the best interest of arrestees to get help from people with little to no legal experience works out best for the NYPD and its apparent desire to engage in as much unconstitutional questioning as possible.

It’s not like this is just reform for the sake of reform. It’s the desire to prevent the NYPD from adding to the long list of false confessions and rights violations perpetrated by law enforcement agencies across the nation against minors they’ve arrested. There’s nothing theoretical about the potential harm. There are plenty of real life cases found everywhere in the nation.

Ciaramella highlights just one of them — a case that shows exactly why the NYPD wants children to have access to no one but parents, as well as why this reform effort is sorely needed.

Reason reported in 2021 on the case of Lawrence Montoya, who at the age of 14 falsely confessed to being at the scene of a murder after several hours of being badgered by two Denver police detectives. Montoya’s mother was present for the first part of the interview. She encouraged him to talk and eventually left her son alone in the interrogation room with detectives, allowing them to lean on him until he gave them what they wanted: a flimsy confession constructed with the facts that they had fed to Montoya.

That’s what the NYPD prefers: parents who will likely suggest cooperation is the best route and leave it in the hands of professionals who want to secure confessions and convictions, rather than actually seek justice.

Filed Under: children, civil rights, lawyers, minors, nypd, public defenders, representation

AI Lawyer Will Represent Client In Traffic Court, Threatening Nonexistent Market For Traffic Court Lawyers

from the if-it-can-make-it-there,-can-it-make-it-anywhere? dept

It’s the rise of the lawbots, something not even foretold by Futurama, which allowed a “simple hyper-chicken from a backwoods asteroid” to perform much of the series’ criminal justice work.

AI-in-everything is on the rise. And that includes lowball court cases, as Lauren Leffer reports for Gizmodo.

An AI-based legal advisor is set to play the role of a lawyer in an actual court case for the first time. Via an earpiece, the artificial intelligence will coach a courtroom defendant on what to say to get out of the associated fines and consequences of a speeding charge, AI-company DoNotPay has claimed in a report initially from New Scientist and confirmed by Gizmodo.

The in-person speeding ticket hearing is scheduled to take place in a U.S. courtroom (specifically, not California) sometime in February, DoNotPay’s founder and CEO Joshua Browder told Gizmodo in a phone call. However, Browder and the company wouldn’t provide any further case details to protect the defendant’s privacy.

AI legal representation in an actual court case will be happening. But, as the saying goes, who knows where or when. The smart money is on February, at least according to the New Scientist report linked to by Gizmodo. Where remains a mystery, but it’s traffic court, so the location doesn’t really matter.

Browder’s DoNotPay bot has been around for a few years at this point. It was originally created to help people fight bogus parking tickets, a suitably low stakes environment for testing the power of the legal AI. It experienced a lot of early success — a 64% success rate in 250,000 cases involving more than $4 million in fines. But that targeted a legal arena where challenges are anomalies and the stakes low enough cities will often dismiss tickets rather than bear the expense of addressing challenges by drivers.

The same thing applies to traffic court. The stakes are low. The odds of success are rather high, considering it can take nothing more than the ticketing officer’s inability to attend court to secure a win for the driver.

And there’s nothing wrong with providing AI assistance to people who have nothing more than a bit of money at stake. Whatever helps even the odds is a welcome addition to a process that pretty much ignores the presumption of innocence mainly because so few people bother to take the time to show up in court to challenge tickets.

That Browder has decided his AI might be capable of securing people’s literal freedom is more concerning. In 2017, he added functionality to assist immigrants with their asylum applications. Immigration law is much more complex than traffic law, and there’s a good chance the use of Browder’s AI may have made things worse for some applicants simply because there are a lot more inscrutable variables involved.

That being said, asking an AI to defend you in traffic court is a good test environment that is likely to have little effect on life or liberty, no matter the outcome. But not all vehicle infractions are low stake. In fact, challenges to the long-used practice of “chalking” tires to determine how long a vehicle has been parked have resulted in two appellate level decisions, with one finding this practice to be a violation of Fourth Amendment rights. So, in some cases, the issue may appear to be negligible while still in traffic court, but may have greater constitutional implications once freed of those confines by shrewd lawyering.

Then there are the negative side effects of being represented by an algorithm. While most traffic court dispensations rely on rote recitals by judges and ticketed drivers, a few don’t. And while most courts are willing to grant more leeway to laypeople representing themselves, it seems unlikely (human) judges will do the same when it becomes clear they’re dealing with an AI interloper that (without doing anything) insinuates it’s smarter than the average defendant, not to mention the average judge.

Browder has addressed this possibility of AI reliance being a net negative for this defendant, but he does so a bit too blithely:

The CEO said the company is also working with another U.S.-based speeding ticket defendant in a case that will go to Zoom trial. In that instance, DoNotPay is weighing the use of a teleprompter vs. a synthetic voice—the latter strategy Browder described as “highly illegal.” But he’s not too concerned about legal repercussions because “at the end of the day, it’s a traffic ticket.” Browder doesn’t expect courts to come down hard on speeding defendants over AI-coaching, and the law doesn’t have explicit provisions in it barring AI-legal assistance. Plus, “it’s an experiment and we like to take risks,” he added.

This is not to say AI has no business operating in the legal field. In traffic cases where someone’s driving privileges or freedom is not on the line, AI assistance may help, especially when the person its aiding has no legal expertise.

And lawyers may find AI useful while seeking relevant precedent or composing briefs and contracts, what with AI’s willingness to plumb the depths of legal rulings and corporate boilerplate to find solutions. But it’s unlikely (or, at least, incredibly unwise) people facing serious legal issues, like lawsuits or criminal charges, will rely on AI to get them out of a legal jamb. Good lawyers are good not just because they know the law. They also know the system and, most importantly, the people operating it. An AI can’t easily duplicate personal relationships with opposing counsel. Nor can it easily take advantage of unforced errors by legal opponents.

But in areas where lawyers are seldom retained, and users fully apprised of the limitations of the AI they’re relying on (which may find new, truly surprising ways to fail when navigating untested areas), there’s probably little harm in asking for some help when attempting to save a few bucks by challenging a bogus ticket. For everything else, actual people — as fallible as they can be — are still the best bet.

Filed Under: ai, court, gpt, joshua bowder, lawyers, legal ai

Companies: donotpay

Madison Square Garden’s Facial Recognition Tech Boots Lawyers Litigating Against The Venue

from the ejecting-your-enemies-under-the-guise-of-venue-safety dept

A private company can legally declare it has the right to refuse service to anyone (with a very small number of limitations under the law, mostly around discrimination against protected classes). The application of facial recognition tech makes it much easier to do. Rather than post photos and bad checks on the back wall to inform employees who isn’t welcome, companies can utilize tech companies and their databases of unknown provenance to make these calls for them.

MSG Entertainment — the company running New York’s Madison Square Garden and other venues — has chosen to turn over its doorman duties to facial recognition tech. Setting aside the fact (for the sake of argument) that this tech tends to subject minorities and women to higher rates of false positives/negatives, recent events at MSG Entertainment-owned venues suggest maybe it’s not a wise idea to do certain things just because you can.

For instance, this mini-debacle, which involved separating a mother from her Girl Scout daughter when both were trying to attend a show at Radio City Music Hall:

Kelly Conlon and her daughter came to New York City the weekend after Thanksgiving as part of a Girl Scout field trip to Radio City Music Hall to see the Christmas Spectacular show. But while her daughter, other members of the Girl Scout troop and their mothers got to go enjoy the show, Conlon wasn’t allowed to do so.

That’s because to Madison Square Garden Entertainment, Conlon isn’t just any mom. They had identified and zeroed in on her, as security guards approached her right as he got into the lobby.

Conlon was approached by security, who told her the facial recognition system had flagged her. They asked for identification and then proceeded to eject her from the venue. No explanation was given, but Kelly Conlon has reason to believe the ejection was personal.

“They knew my name before I told them. They knew the firm I was associated with before I told them. And they told me I was not allowed to be there,” said Conlon.

Conlon is an associate with the New Jersey based law firm, Davis, Saperstein and Solomon, which for years has been involved in personal injury litigation against a restaurant venue now under the umbrella of MSG Entertainment.

Was Conlon reading too much into this? If this were an isolated incident, the answer might be “possibly.” But Conlon isn’t the only lawyer working for a firm involved in litigation against MSG that has been refused entry by the company’s facial recognition tech:

A Long Island attorney says he was kicked out of a Knicks game after getting flagged by facial recognition technology at Madison Square Garden — the same system the company used to boot another lawyer from a Rockettes show.

“I was upset — we had a whole night planned out that got botched,” said lawyer Alexis Majano, 28. “I said, ‘This is ridiculous.’”

Majano — whose law firm has a pending lawsuit against Madison Square Garden Entertainment in an unrelated matter — was headed into the game against the Celtics with pals on Nov. 5 when he was stopped on an escalator, he said.

Majano works for law firm Sahn Ward Braff Koblenz. The firm recently filed a lawsuit on behalf of a person who fell from a skybox at Madison Square Garden while attending a concert. He’s just one of several lawyers who have apparently been banned from attending events hosted by MSG Entertainment simply because they work for firms engaged in litigation against the company.

These bans are now leading to lawsuits. And these lawsuits target ejections dating back to this summer, when lawyers started to notice a strange pattern of ejections targeting members of law firms engaged in litigation targeting MSG Entertainment.

While private companies do retain the right to refuse service to anyone for nearly any reason, the question being asked is whether being adjacent to litigation is a legal reason to refuse service, especially since the ejections occur after MSG Entertainment has already chosen to sell tickets to people it then ejects when they arrive to make use of their purchased goods.

Legal or not, the optics are terrible. Not that it appears to matter to the person running the company.

Its chief executive, James L. Dolan, is a billionaire who has run his empire with an autocratic flair, and his company instituted the ban this summer not only on lawyers representing people suing it, but on all attorneys at their firms. The company says “litigation creates an inherently adversarial environment” and so it is enforcing the list with the help of computer software that can identify hundreds of lawyers via profile photos on their firms’ own websites, using an algorithm to instantaneously pore over images and suggest matches.

It’s a free market. There’s no Constitutionally-guaranteed right to event attendance. Private companies can, for the most part, pick and choose who they want to do business with. But deploying unproven tech with a proven track record of being wrong far too often puts people at the mercy of both billionaires and whatever method they’ve picked to increase ejection efficiency. If MSG is concerned lawyers might be trying to gain an edge by attending events simply to do some snooping, it seems it might be able to find a court-based solution that serves this purpose.

This is a bad look for MSG, even if it’s completely legal. It indicates it doesn’t have much confidence in its defense against these lawsuits. It also indicates the facial recognition tech systems aren’t there to ensure public safety, but rather to allow MSG Entertainment to refuse entry to anyone it considers to be an enemy. And if it continues to work this well, it will encourage other businesses to do the same thing: silence critics by simply refusing to allow them entry.

And it’s a tactic that’s pretty much guaranteed to encourage at least the state’s government — via court decisions or legislation — to issue mandates that restrict the private rights of businesses. In the long run, this probably isn’t going to work out for MSG’s management. And, until it’s all settled, the company can continue to punish its perceived enemies for committing the offense of providing legal services to people who feel they’ve been wronged by MSG Entertainment. If MSG wants to prove it’s in the right, let it do it in court. Deploying sketchy tech to blacklist people who’ve never violated any venue rules is a terrible way to handle a “problem” that appears to only exist in the mind of the MSG’s owner.

Filed Under: ejected, facial recognition, james dolan, lawyers, msg

Companies: msg, msg entertainment

Being A Supreme Court Clerk Now Hazardous To Your Privacy

from the tradeoffs dept

As you certainly remember, last month Politico published a draft opinion, written by Justice Alito, overturning Roe v. Wade. The final ruling has not yet come out, but is expected soon (as the Supreme Court session is nearing its conclusion). There has been tremendous speculation over who leaked the draft (and why). There has been lots of pointing fingers and assumptions, but the truth is that almost no one actually knows other than whoever leaked it, and the journalists who received it. Much of the speculation has fallen on the law clerks at the Supreme Court — the recent law school grads who often do a lot of the work on the cases that come before the court.

Some people insist that it must have been left-leaning clerks who were alarmed at the draft opinion, while others have suggested that it may have been right-leaning clerks who were worried that support for Alito’s opinion was waning, and hoping to shore up the support. Again, as of right now, we have no idea. Reports suggest that somewhere around 75 people may have had access to the draft, including the Justices, their clerks, and various other people working at the Court.

However, as a recent CNN report notes, the investigation into the leak, as demanded by Chief Justice Roberts, and carried out by the Court’s marshal, is apparently focusing on the clerks, including “taking steps to require law clerks provide cell phone records and sign affidavits.” That has raised an awful lot of eyebrows.

At the very least, this puts basically all clerks (yes, including any or all of them who didn’t leak the draft) in a precarious position. Given the risk of legal exposure, clerks almost certainly need to lawyer up. And by legal exposure, I don’t just mean for whoever may have leaked the draft. Signing an affidavit also can put them at risk:

By signing an affidavit, if what they sign isn’t true, clerks open up themselves to criminal liability that likely isn’t present by simply leaking the opinion draft. That is because false statements to government investigators — including in written statements — is a federal crime that carries up to five years in prison.

So, that’s the kind of thing that you would want to have a lawyer review. And yet, of course, hiring a lawyer is often (falsely, and somewhat ridiculously) seen as a sign of guilt. One hopes that the Supreme Court, of all places, would recognize why that’s bullshit, but you never know.

“The clerks are probably the most vulnerable workers who had access to that information in the building, because their career could be dramatically affected by how they chose to respond,” Catherine Fisk, a professor of employment law at UC Berkeley School of Law, told CNN. The basic act of lawyering up could create an inference of guilt “is certainly a fear that they would have.”

And, of course, there are questions about what happens when you allow your employer to look through your phone records, again, even if you’re not the leaker.

Will investigators be able to scoop up data about clerk conduct not related to the leak? Could that data be used against the clerks in a criminal context, or even to justify disciplinary action against them?

“Or it could include information about a friend or family member of a clerk who is engaged in conduct that is unlawful,” Fisk said, noting that in criminal investigations, such information is often used as leverage to get information investigators really want.

Then there’s the possibility of investigation picking up sensitive conversations clerks had about other justices or other clerks — with the potential of further inflaming tensions at time when trust within the Supreme Court’s walls has bottomed out.

That article also quotes law professor Laurence Tribe noting that it would “be entirely appropriate” for the law clerks to refuse to share their cell phone records, but recognizes that there could be significant consequences, including losing their clerkship, and taking a big reputational hit for doing so (not to mention the rumor mill that would certainly accuse them of leaking).

There are some questions about whether or not the clerks might be protected under so called “Garrity Rights” that supposedly protect public employees from incriminating themselves (based on a 1967 Supreme Court case), but others suggest that, depending on lots of important, but unknown details, that might not apply here.

At the very least, it seems like the current crop of Supreme Court clerks may have a newfound understanding of the privacy issues related to their own cell phone records. One hopes that they, and future clerks, remember this the next time a 4th Amendment case regarding cell phone records hits the court’s docket, though I’m guessing that they will assume “that’s different.”

Filed Under: cell phone records, clerks, lawyers, leaks, privacy, self-incrimination, supreme court, supreme court clerks