matt taibbi – Techdirt (original) (raw)

Substackerati’s ‘Grave Concerns’ About White House/Big Tech Collusion Have Disappeared With Elon’s Ascension

from the (sub)stack-of-hypocrites dept

For years, a vocal group of self-described “contrarian” Substackified pundits warned about a supposed “censorship industrial complex” involving collusion between the White House and social media companies to set content moderation policies. There was just one problem: it wasn’t even close to true.

Now, with Elon Musk owning ExTwitter and Donald Trump heading back to the White House, we have a situation that actually matches what those contrarian chroniclers claimed to fear: powerful tech moguls with direct ties to the administration in a position to influence online speech. Suddenly, the grave concerns about “creeping authoritarianism” have evaporated. The double standard couldn’t be more blatant.

So, I figured it was worth calling out the hypocrisy, and MSNBC kindly gave me the space to do so:

The so-called Twitter Files, hyped by Elon Musk and handpicked journalists, were touted as smoking-gun proof of a vast conspiracy between social media and the government to violate the First Amendment. Testifying before Congress, these reporters called it a “grave threat” and evidence of “creeping authoritarianism.”

Flash forward to today. Donald Trump is heading back to the White House. And Musk, owner of the social media company X (formerly Twitter), is a top donor, surrogate and soon-to-be government “efficiency” overseer. Musk has openly used his platform to boost Trump, attack his opponents and shape the political narrative. The collusion between government and Big Tech is no longer a conspiracy theory — it’s out in the open.

Yet suddenly, all those grave concerns about the threat to democracy have evaporated. Most of the same voices who warned of shocking government overreach in the pre-Musk Twitter era are either silent about this turn of events or they’re in wild celebration of the Trump-Musk alliance. This reveals the issue wasn’t a matter of principle; it was a matter of party.

The limited space in the MSNBC piece prevented me from delving into the additional hypocrisy around how swiftly Elon Musk banned a reporter and links related to the leaked JD Vance dossier. This action was an even more extreme version of what GOP pundits have baselessly claimed Twitter did with the New York Post’s Hunter Biden laptop story.

Yet, even as the completely exaggerated claims about what happened with Twitter and the Hunter laptop are still regularly brought up by the MAGA faithful, the story about Elon and the Vance dossier disappeared after, what, two days?

But, really, the piece takes aim at the Elon/Trump enablers. The Sophist Substackerati who position themselves as brave truth tellers, standing up to government overreach: the Matt Taibbis, Michael Shellenbergers, and Bari Weisses of the world, who all seem to have forgotten what they were saying not too long ago about the hallucinated story of coziness between the White House and social media.

Taibbi called it “a grave threat to people of all political persuasions.” Shellenberger called it “the shocking and disturbing emergence of State-sponsored censorship.” A reporter from The Free Press — a publication created by Bari Weiss (another Twitter Files reporter) — Rupa Subramanya, testified in one of these hearings warning that the American government was heading down a dangerous path of censorship, calling government connections to social media “creeping authoritarianism.”

But, oh, how things have changed.

Elon Musk still owns X. Donald Trump still owns Truth Social. These are two social media networks that can drive the news and conversations about important events in the world.

Unlike before, when there was conjecture (without evidence) of grand conspiracies and connections between the White House and important social media companies, now it’s completely explicit and out in the open.

Yet, all talk of the “grave threats” and “shocking and disturbing” connections between the White House and social media have disappeared entirely. Shellenberger has called the new administration “cathartic.” Taibbi has posted numerous articles celebrating the results of the election. The Free Press has a bunch of articles praising the new Trump administration and celebrating how the election was “a win for a new generation of builders like Elon Musk.”

The “Twitter Files” pundits built their brands on a false narrative of anti-establishment rebellion against the “elite” trying to control social media. But when faced with the real thing, they’re too busy high-fiving each other to care. Their “grave concerns” about government collusion with Big Tech have suddenly evaporated now that the administration and the tech mogul are their ideological allies.

Or, as I note:

Turns out for the “Twitter Files” crew, “creeping authoritarianism” isn’t so creepy when it’s your team doing the creeping.

There’s a lot more in the piece, but I want to point out why it’s so important to call out this hypocrisy. I know that there are a bunch of cynical “too savvy for school” folks who always respond to things like this by saying “what, it surprises you that they were full of shit?”

No, it doesn’t surprise me at all. I’ve been calling out this kind of nonsense for years. But people who don’t follow this stuff closely don’t know this. There are so many times where I hear something these nonsense peddlers pushed over and over again pop up in the mainstream media or among random people who just assume what they’re saying is accurate.

Calling out the hypocrisy isn’t to impact those in the Intellectual Derp Web. They have their captured audiences and have made it clear they don’t give a shit. But it’s important to remind everyone else what the grift is here. The cluelessness, the gaslighting, and the utter nonsense they spent years spreading for clout. Some of us recognize it for what it was.

We need to keep telling people and reminding people so that everyone else knows it’s bullshit too.

Filed Under: bari weiss, censorship industrial complex, contrarians, donald trump, elon musk, hypocrisy, matt taibbi, michael shellenberger, nonsense peddlers

Companies: truth social, twitter, x

Supporting Free Speech Means Supporting Victims Of SLAPP Suits, Even If You Disagree With The Speakers

from the no-free-speech-tourism dept

When Elon filed his recent ridiculous SLAPP suit against Media Matters, it was noteworthy (but not surprising) to me to see people who not only claimed to be “free speech supporters,” but who made that a key part of their persona, cheering on the lawsuit, even though its only purpose was to use the power of the state to stifle and suppress free speech.

Matt Taibbi, for example, has spent the last year insisting that the Twitter Files, which he has totally misread and misrepresented, are one of the biggest “free speech” stories of our times. Indeed, he just won some made up new award worth $100k for “excellence in investigative journalism,” and in his “acceptance speech” he argued about how free speech was under attack and needed to be defended.

Just a few weeks later, he was cheering on Musk’s decision to sue Media Matters over journalism Taibbi didn’t like and didn’t support. Taibbi argues that the lawsuit is okay because it accuses Media Matters of “creating a news story, reporting on it, _then propagandizing it to willing partners in the mainstream media._” Except, um, dude, that’s exactly the same thing you did with the Twitter Files story, propagandizing it to Fox News and other nonsense peddling networks.

Of course, Taibbi has every right to be terrible at the job of being a journalist. He has every right to not understand the documents put in front of him. He has every right to leave out the important context that explains what he’s seeing (either because he’s too clueless to understand it, or because of motivated reasoning and the need to feed an audience of ignorant clods who pay him). He even has every right to make the many, many factual mistakes he made in his reporting, which undermine the central premise of that reporting. That’s free speech.

If Taibbi were sued over his reporting, I’d stand up and point out how ridiculous it is and how such a lawsuit is an attack on his free speech rights, and a clear SLAPP suit. Taibbi may deserve to be ridiculed for his ignorance and credulity, but he should never face legal consequences for it.

But, according to Taibbi himself, it’s okay for someone who is the victim of that kind of bad reporting to sue and run journalists through the destructive process of a SLAPP suit, because if a story is “propagandized” then it’s fair game. He even seems kinda gleeful about it, suggesting that all sorts of reporting from the past few years deserves similar treatment, whether it was reporting about Donald Trump’s alleged connections to Russia or things about COVID — that all of it is now fair game if it was misleadingly sensationalized (again, the very same thing he, himself, has been doing, just for a different team).

That’s not supporting free speech. That’s exactly what they accuse others of doing: of only supporting free speech when you agree with it. And it’s cheering on an actual, blatant, obvious abuse of the state to try to stifle speech.

So, let’s go back to Musk’s other SLAPP suit, which he filed earlier this year against the Center for Countering Digital Hate, claiming that their reporting about hateful content on ExTwitter somehow violated a contract (originally, Musk’s personal lawyer threatened CCDH with defamation, but that’s not what they filed).

As I made clear at the time, I think CCDH is awful. I think their research methodologies are terrible. I think they play fast and loose with the details in their rush to blame social media for all sorts of ills in the world. Hell, just weeks before the lawsuit I dismantled a CCDH study that was being relied upon by California legislators to try to pass a terrible bill regarding kids and social media. The study was egregiously bad, to the point of arguing that photos of gum on social media were “eating disorder content.”

I would never trust anything that CCDH puts out. I think that their slipshod methodology undermines everything they do to the point that I’d never rely on anything they said as being accurate, because they have zero credibility with me.

But, unlike Taibbi, I would never cheer on a SLAPP suit against them. I still stand up for CCDH’s free speech rights to publish the studies they publish and to speak up about what they believe without then being sued and facing legal consequences for stating their opinions.

That’s why I was happy that the Public Participation Project, a non-profit working to pass more anti-SLAPP laws across the country, where I am a board member, decided to work with the Harvard Cyberlaw clinic to file an amicus brief in support of CCDH, calling out how Musk’s lawsuit against them is an obvious SLAPP suit. Full disclosure: the Public Participation Project did ask me how I felt about the organization submitting this brief before deciding to take it on, knowing my own reservations about CCDH’s work. I told them I supported the filing wholeheartedly and am proud to see the organization doing the right thing and standing up against a SLAPP suit, even if (perhaps especially because!) I disagree with what CCDH says.

The filing, written by the amazing Kendra Albert, makes some key points. The original lawsuit was framed as a “breach of contract” lawsuit in a thinly veiled attempt to avoid an anti-SLAPP claim, since ExTwitter will certainly claim contract issues have nothing to do with speech.

But as the Public Participation Project’s filing makes clear, there is no way to read that lawsuit without realizing it’s an attempt to punish CCDH for its speech and silence similar such speech:

By suing the Center for Countering Digital Hate (“CCDH”), X Corp. (formerly Twitter), seeks to silence critique rather than to counter it. X Corp.’s claims may sound in breach of contract, intentional interference with contractual relations, and inducing breach of contract (hereinafter “state law claims”), rather than being explicitly about CCDH’s speech. But its arguments and its damages calculations rest on the decisions of advertisers to no longer work with X Corp. as a result of CCDH’s First Amendment protected activity. In brief, this is a classic Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation (SLAPP). X Corp. aims not to win but to chill.

Fortunately, the California anti-SLAPP statute, Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 425.16, provides protection against abuse of the legal system with the goal of suppressing speech. X Corp.’s claims arise from CCDH’s protected activity and relate to a matter of public interest, making it appropriate for the anti-SLAPP statute to apply. Indeed, the anti-SLAPP statute’s purpose requires its application to these claims.

No doubt recognizing this, X Corp. seeks to do through haphazardly constructed contractual claims what the First Amendment does not permit it to do through speech torts. The harm that the anti-SLAPP statute aims to prevent will be realized if this court allows X Corp.’s claims to continue. The statute provides little help if plaintiffs can easily plead around it.

Indeed, X Corp.’s legal theories, if accepted by this court, could chill broad swathes of speech. If large online platforms can weaponize their terms of service against researchers and commentators they dislike, they may turn any contract of adhesion into a “SLAPP trap.” Organizations of all types could hold their critics liable for loss of revenue from the organization’s own bad acts, so long as a contractual breach might have occurred somewhere in the causal chain.

X Corp.’s behavior has already substantially chilled researchers and advocates, and it shows no signs of stopping. Since this litigation was filed, its Chief Technology Officer has threatened organizations with litigation because they have commented on X Corp.’s policies in a way that he dislikes. And on November 20, 2023, X Corp. filed another lawsuit against a non-profit organization for reporting its findings about hate speech on X. Organizations and individuals must be able to engage in research around the harms and benefits of social media platforms and they must be able to publish that research without fear of a federal lawsuit if their message is too successful.

Standing up for free speech means standing up against using the power of the state, including the courts, to attack and suppress speech you dislike. As much as I disagree with CCDH’s conclusions and the methodology behind many of its reports, unlike supposed “free speech warriors” cheering on Musk’s lawsuits against the likes of CCDH and Media Matters, I’m proud that an organization I’m associated with is willing to stand on principle and argue for actual free speech.

Hopefully, the courts will recognize this as well. And hopefully more people will begin to realize just how thin and fake the claims of other “free speech” supporters are. Not through lawsuits, but just by seeing what they actually do in practice when true threats to free speech arrive.

Filed Under: anti-slapp, california, elon musk, free speech, matt taibbi, slapp suits

Companies: ccdh, twitter, x

Stop Letting Nonsense Purveyors Cosplay As Free Speech Martyrs

from the oh,-i-do-declare-westminster dept

A few people have been asking me about last week’s release of something called the “Westminster Declaration,” which is a high and mighty sounding “declaration” about freedom of speech, signed by a bunch of journalists, academics, advocates and more. It reminded me a lot of the infamous “Harper’s Letter” from a few years ago that generated a bunch of controversy for similar reasons.

In short, both documents take a few very real concerns about attacks on free expression, but commingle them with a bunch of total bullshit huckster concerns that only pretend to be about free speech, in order to legitimize the latter with the former. The argument form is becoming all too common these days, in which you nod along with the obvious stuff, but any reasonable mind should stop and wonder why the nonsense part was included as well.

It’s like saying war is bad, and we should all seek peace, and my neighbor Ned is an asshole who makes me want to be violent, so since we all agree that war is bad, we should banish Ned.

The Westminster Declaration is sort of like that, but the parts about war are about legitimate attacks of free speech around the globe (nearly all of which we cover here), and the parts about my neighbor Ned are… the bogus Twitter Files.

The Daily Beast asked me to write up something about it all, so I wrote a fairly long analysis of just how silly the Westminster Declaration turns out to be when you break down the details. Here’s a snippet:

I think there is much in the Westminster Declaration that is worth supporting. We’re seeing laws pushed, worldwide, that seek to silence voices on the internet. Global attacks on privacy and speech-enhancing encryption technologies are a legitimate concern.

But the Declaration—apparently authored by Michael Shellenberger and Matt Taibbi, along with Andrew Lowenthal, according to their announcement of the document—seeks to take those legitimate concerns and wrap them tightly around a fantasy concoction. It’s a moral panic of their own creation, arguing that separate from the legitimate concern of censorial laws being passed in numerous countries passed, there is something more nefarious—what they have hilariously dubbed “the censorship-industrial complex.”

To be clear, this is something that does not actually exist. It’s a fever dream from people who are upset that they, or their friends, violated the rules of social media platforms and faced the consequences.

But, unable to admit that private entities determining their own rules is an act of free expression itself (the right not to associate with speech is just as important as the right to speak), the crux of the Westminster Declaration is an attempt to commingle legitimate concerns about government censorship with grievances about private companies’ moderation decisions.

You can click through to read the whole thing…

Filed Under: free seech, matt taibbi, michael shellenberger, moral panic, twitter files, westminster declaration

Companies: twitter

Twitter Admits in Court Filing: Elon Musk Is Simply Wrong About Government Interference At Twitter

from the confirmation-idiocy dept

It is amazing the degree to which some people will engage in confirmation bias and believe absolute nonsense, even as the facts show the opposite is true. Over the past few months, we’ve gone through the various “Twitter Files” releases, and pointed out over and over again how the explanations people gave for them simply don’t match up with the underlying documents.

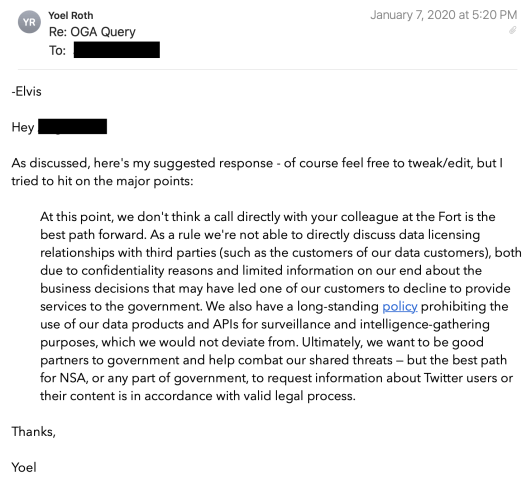

To date, not a single document revealed has shown what people now falsely believe: that the US government and Twitter were working together to “censor” people based on their political viewpoints. Literally none of that has been shown at all. Instead, what’s been shown is that Twitter had a competent trust & safety team that debated tough questions around how to apply policies for users on their platform and did not seem at all politically motivated in their decisions. Furthermore, while various government entities sometimes did communicate with the company, there’s little evidence of any attempt by government officials to compel Twitter to moderate in any particular way, and Twitter staff regularly and repeatedly rebuffed any attempt by government officials to go after certain users or content.

Now, as you may recall, two years ago, a few months after Donald Trump was banned from Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, he sued the companies, claiming that the banning violated the 1st Amendment. This was hilariously stupid for many reasons, not the least of which is because at the time of the banning Donald Trump was the President of the United States, and these companies were very much private entities. The 1st Amendment restricts the government, not private entities, and it absolutely does not restrict private companies from banning the President of the United States should the President violate a site’s rules.

As expected, the case went poorly for Trump, leading to it being dismissed. It is currently on appeal. However, in early May, Trump’s lawyers filed a motion to effectively try to reopen the case at the district court, arguing that the Twitter Files changed everything, and that now there was proof that Trump’s 1st Amendment rights were violated.

In October of 2022, after the entry of this Court’s Judgment, Twitter was acquired by Elon Musk. Shortly thereafter, Mr. Musk invited several journalists to review Twitter’s internal records. Allowing these journalists to search for evidence that Twitter censored content that was otherwise compliant with Twitter’s “TOS”, the journalists disclosed their findings in a series of posts on Twitter collectively known as the Twitter Files. As set out in the attached Rule 60 motion, the Twitter Files confirm Plaintiffs’ allegations that Twitter engaged in a widespread censorship campaign that not only violated the TOS but, as much of the censorship was the result of unlawful government influence, violated the First Amendment.

I had been thinking about writing this up as a story, but things got busy, and last week Twitter (which, again, is now owned by Elon Musk who has repeatedly made ridiculously misleading statements about what the Twitter Files showed) filed its response, where they say (with risk of sanctions on the line) that this is all bullshit and nothing in the Twitter Files says what Trump (and Elon, and a bunch of his fans) claim it says. This is pretty fucking damning to anyone who believed the nonsense Twitter Files narrative.

The new materials do not plausibly suggest that Twitter suspended any of Plaintiffs’ accounts pursuant to any state-created right or rule of conduct. As this Court held, Lugar’s first prong requires a “clear,” government-imposed rule. Dkt. 165 at 6. But, as with Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint, the new materials contain only a “grab-bag” of communications about varied topics, none establishing a state-imposed rule responsible for Plaintiffs’ challenged content-moderation decisions. The new materials cover topics ranging, for example, from Hunter Biden’s laptop, Pls.’ Exs. A.14 & A.27-A.28, to foreign interference in the 2020 election, Pls.’ Exs. A.13 at, e.g., 35:15-41:4, A.22, A.37, A.38, to techniques used in malware and ransomware attacks, Pls.’ Ex. A.38. As with the allegations in the Amended Complaint, “[i]t is … not plausible to conclude that Twitter or any other listener could discern a clear state rule” from such varied communications. Dkt. 165 at 6. The new materials would not change this Court’s dismissal of Plaintiffs’ First Amendment claims for this reason alone.

Moreover, a rule of conduct is imposed by the state only if backed by the force of law, as with a statute or regulation. See Sutton v. Providence St. Joseph Med. Ctr., 192 F.3d 826, 835 (9th Cir. 1999) (regulatory requirements can satisfy Lugar’s first prong). Here, nothing in the new materials suggests any statute or regulation dictating or authorizing Twitter’s content-moderation decisions with respect to Plaintiffs’ accounts. To the contrary, the new materials show that Twitter takes content-moderation actions pursuant to its own rules and policies. As attested to by FBI Agent Elvis Chan, when the FBI reported content to social media companies, they would “alert the social media companies to see if [the content] violated their terms of service,” and the social media companies would then “follow their own policies” regarding what actions to take, if any. Pls.’ Ex. A.13 at 165:9-22 (emphases added); accord id. at 267:19-23, 295:24-296:4. And general calls from the Biden administration for Twitter and other social media companies to “do more” to address alleged misinformation, see Pls.’ Ex. A.47, fail to suggest a state-imposed rule of conduct for the same reasons this Court already held the Amended Complaint’s allegations insufficient: “[T]he comments of a handful of elected officials are a far cry from a ‘rule of decision for which the State is responsible’” and do not impose any “clear rule,” let alone one with the force of law. Dkt. 165 at 6. The new materials thus would not change this Court’s determination that Plaintiffs have not alleged any deprivation caused by a rule of conduct imposed by the State.

Later on it goes further:

Plaintiffs appear to contend (Pls.’ Ex. 1 at 16-17) that the new materials support an inference of state action in Twitter’s suspension of Trump’s account because they show that certain Twitter employees initially determined that Trump’s January 2021 Tweets (for which his account was ultimately suspended) did not violate Twitter’s policy against inciting violence. But these materials regarding Twitter’s internal deliberations and disagreements show no governmental participation with respect to Plaintiffs’ accounts. See Pls.’ Exs. A.5.5, A-49-53.5

Plaintiffs are also wrong (Ex. 1 at 15-16) that general calls from the Biden administration to address alleged COVID-19 misinformation support a plausible inference of state action in Twitter’s suspensions of Cuadros’s and Root’s accounts simply because they “had their Twitter accounts suspended or revoked due to Covid-19 content.” For one thing, most of the relevant communications date from Spring 2021 or later, after Cuadros and Roots’ suspensions in 2020 and early 2021, respectively, see Pls.’ Ex. A.46-A.47; Am. Compl. ¶¶124, 150. Such communications that “post-date the relevant conduct that allegedly injured Plaintiffs … do not establish [state] action.” Federal Agency of News LLC v. Facebook, Inc., 432 F. Supp. 3d 1107, 1125-26 (N.D. Cal. 2020). Additionally, the new materials contain only general calls on Twitter to “do more” to address COVID-19 misinformation and questions regarding why Twitter had not taken action against certain other accounts (not Plaintiffs’). Pls.’ Exs. A.43-A.48. Such requests to “do more to stop the spread of false or misleading COVID-19 information,” untethered to any specific threat or requirement to take any specific action against Plaintiffs, is “permissible persuasion” and not state action. Kennedy v. Warren, 66 F.4th 1199, 1205, 1207-12 (9th Cir. 2023). As this Court previously held, government actors are free to “urg[e]” private parties to take certain actions or “criticize” others without giving rise to state action. Dkt. 165 at 12-13. Because that is the most that the new materials suggest with respect to Cuadros and Root, the new materials would not change this Court’s dismissal of their claims.

Twitter’s filing is like a beat-by-beat debunking of the conspiracy theories pushed by the dude who owns Twitter. It’s really quite incredible.

First, the simple act of receiving information from the government, or of deciding to act upon that information, does not transform a private actor into a state actor. See O’Handley, 62 F.4th at 1160 (reports from government actors “flagg[ing] for Twitter’s review posts that potentially violated the company’s content-moderation policy” were not state action). While Plaintiffs have attempted to distinguish O’Handley on the basis of the repeated communications reflected in the new materials, (Ex. 1 at 13), O’Handley held that such “flag[s]” do not suggest state action even where done “on a repeated basis” through a dedicated, “priority” portal. Id. The very documents on which Plaintiffs rely establish that when governmental actors reported to social media companies content that potentially violated their terms of service, the companies, including Twitter, would “see if [the content] violated their terms of service,” and, “[i]f [it] did, they would follow their own policies” regarding what content-moderation action was appropriate. Pls.’ Ex. A.13 at 165:3-17; accord id. at 296:1-4 (“[W]e [the FBI] would send information about malign foreign influence to specific companies as we became aware of it, and then they would review it and determine if they needed to take action.”). In other words, Twitter made an independent assessment and acted accordingly.

Moreover, the “frequen[t] [] meetings” on which Plaintiffs rely heavily in attempting to show joint action fall even farther short of what was alleged in O’Handley because, as discussed supra at 7, they were wholly unrelated to the kinds of content-moderation decisions at issue here.

Second, contrary to Plaintiffs’ contention (Ex. 1 at 11-12), the fact that the government gave certain Twitter employees security clearance does not transform information sharing into state action. The necessity for security clearance reflects only the sensitive nature of the information being shared— i.e., efforts by “[f]oreign adversaries” to “undermine the legitimacy of the [2020] election,” Pls.’ Ex. A.22. It says nothing about whether Twitter would work hand-in-hand with the federal government. Again, when the FBI shared sensitive information regarding possible election interference, Twitter determined whether and how to respond. Pls.’ Ex. A.13 at 165:3-17, 296:1-4.

Third, Plaintiffs are also wrong (Ex. 1 at 12-13) that Twitter became a state actor because the FBI “pay[ed] Twitter millions of dollars for the staff [t]ime Twitter expended in handling the government’s censorship requests.” For one thing, the communication on which Plaintiffs rely in fact explains that Twitter was reimbursed $3 million pursuant to a “statutory right of reimbursement for time spent processing” “legal process” requests. Pls.’ Ex. A.34 (emphasis added). The “statutory right” at issue is that created under the Stored Communications Act for costs “incurred in searching for, assembling, reproducing, or otherwise providing” electronic communications requested by the government pursuant to a warrant. 18 U.S.C. § 2706(a), see also id. § 2703(a). The reimbursements were not for responding to requests to remove any accounts or content and thus are wholly irrelevant to Plaintiffs’ joint-action theory

And, in any event, a financial relationship supports joint action only where there is complete “financial integration” and “indispensability.” Vincent v. Trend W. Tech. Corp., 828 F.2d 563, 569 (9th Cir. 1987) (quotation marks omitted). During the period in which Twitter recovered 3million(late2019throughearly2021),thecompanywasvaluedatapproximately3 million (late 2019 through early 2021), the company was valued at approximately 3million(late2019throughearly2021),thecompanywasvaluedatapproximately30 billion. Even Plaintiffs do not argue that a $3 million payment would be indispensable to Twitter.

I mean, if you read Techdirt, you already knew about all this, because we debunked the nonsense “government paid Twitter to censor” story months ago, even as Elon Musk was falsely tweeting exactly that. And now, Elon’s own lawyers are admitting that the company’s owner is completely full of shit or too stupid to actually read any of the details in the Twitter files. It’s incredible.

It goes on. Remember how Elon keeps insisting that the government coerced Twitter to make content moderation decisions? Well, Twitter’s own lawyers say that’s absolute horseshit. I mean, much of the following basically is what my Techdirt posts have explained:

The new materials do not evince coercion because they contain no threat of government sanction premised on Twitter’s failure to suspend Plaintiffs’ accounts. As this Court already held, coercion requires “a concrete and specific government action, or threatened action” for failure to comply with a governmental dictate. Dkt. 165 at 11. Even calls from legislators to “do something” about Plaintiffs’ Tweets (specifically, Mr. Trump’s) do not suggest coercion absent “any threatening remark directed to Twitter.” Id. at 7. The Ninth Circuit has since affirmed the same basic conclusion, holding in O’Handley that “government officials do not violate the First Amendment when they request that a private intermediary not carry a third party’s speech so long as the officials do not threaten adverse consequences if the intermediary refuses to comply.” 62 F.4th at 1158. Like the Amended Complaint, the new materials show, at most, attempts by the government to persuade and not any threat of punitive action, and thus would not alter the Court’s dismissal of Plaintiffs’ First Amendment claims.

FBI Officials. None of the FBI’s communications with Twitter cited by Plaintiffs evince coercion because they do not contain a specific government demand to remove content—let alone one backed by the threat of government sanction. Instead, the new materials show that the agency issued general updates about their efforts to combat foreign interference in the 2020 election. For example, one FBI email notified Twitter that the agency issued a “joint advisory” on recent ransomware tactics, and another explained that the Treasury department seized domains used by foreign actors to orchestrate a “disinformation campaign.” Pls.’ Ex. A.38. These informational updates cannot be coercive because they merely convey information; there is no specific government demand to do anything—let alone one backed by government sanction.

So too with respect to the cited FBI emails flagging specific Tweets. The emails were phrased in advisory terms, flagging accounts they believed may violate Twitter’s policies—and Twitter employees received them as such, independently reviewing the flagged Tweets. See, e.g., Pls.’ Exs. A.30 (“The FBI San Francisco Emergency Operations Center sent us the attached report of 207 Tweets they believe may be in violation of our policies.”), A.31, A.40. None even requested—let alone commanded—Twitter to take down any content. And none threatened retaliatory action if Twitter did not remove the flagged Tweets. As in O’Handley, therefore, the FBI’s “flags” cannot amount to coercion because there was “no intimation that Twitter would suffer adverse consequences if it refused.” 62 F.4th at 1158. What is more, unlike O’Handley, not one of the cited communications contains a request to take any action whatsoever with respect to any of Plaintiffs’ accounts.6

Plaintiffs’ claim (Ex. 1 at 14) that the FBI’s “compensation of Twitter for responding to its requests” had coercive force is meritless. As a threshold matter, as discussed supra at 10, the new materials demonstrate only that Twitter exercised its statutory right—provided to all private actors—to seek reimbursement for time it spent processing a government official’s legal requests for information under the Stored Communications Act, 18 U.S.C. § 2706; see also id. § 2703. The payments therefore do not concern content moderation at all—let alone specific requests to take down content. And in any event, the Ninth Circuit has made clear that, under a coercion theory, “receipt of government funds is insufficient to convert a private [actor] into a state actor, even where virtually all of the [the party’s] income [i]s derived from government funding.” Heineke, 965 F.3d at 1013 (quotation marks omitted) (third alteration in original). Therefore, Plaintiffs’ reliance on those payments does not evince coercion.

What about the pressure from Congress? That too is garbage, admits Twitter:

Congress. The new materials do not contain any actionable threat by Congress tied to Twitter’s suspension of Plaintiffs’ accounts. First, Plaintiffs place much stock (Ex. 1 at 14-15) in a single FBI agent’s opinion that Twitter employees may have felt “pressure” by Members of Congress to adopt a more proactive approach to content moderation, Pls.’ Ex. A13 at 117:15-118:6. But a third-party’s opinion as to what Twitter’s employees might have felt is hardly dispositive. And in any event, “[g]enerating public pressure to motivate others to change their behavior is a core part of public discourse,” and is not coercion absent a specific threatened sanction for failure to comply….

White House Officials. The new materials do not evince any actionable threat by White House officials either. Plaintiffs rely (Ex. 1 at 16) on a single statement by a Twitter employee that “[t]he Biden team was not satisfied with Twitter’s enforcement approach as they wanted Twitter to do more and to deplatform several accounts,” Pls.’ Ex. A.47. But those exchanges took place in December 2022, id.— well after Plaintiffs’ suspensions, and so could not have compelled Twitter to suspend their accounts. Furthermore, the new materials fail to identify any threat of government sanction arising from the officials’ “dissatisfaction”; indeed, Twitter was only asked to join “other calls” to continue the dialogue

Basically, Twitter’s own lawyers are admitting in a court filing that the guy who owns their company is spewing utter nonsense about what the Twitter Files revealed. I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything quite like this.

Guy takes over company because he’s positive that there are awful things happening behind the scenes. Gives “full access” to a bunch of very ignorant journalists who are confused about what they find. Guy who now owns the company falsely insists that they proved what he believed all along, leading to the revival of a preternaturally stupid lawsuit… only to have the company’s lawyers basically tell the judge “ignore our stupid fucking owner, he can’t read or understand any of this.”

Filed Under: coercion, content moderation, donald trump, elon musk, elvis chan, fbi, matt taibbi, twitter files

Companies: twitter

After Matt Taibbi Leaves Twitter, Elon Musk ‘Shadow Bans’ All Of Taibbi’s Tweets, Including The Twitter Files

from the a-show-in-three-acts dept

The refrain to remember with Twitter under Elon Musk: it can always get dumber.

Quick(ish) recap:

On Thursday, Musk’s original hand-picked Twitter Files scribe, Matt Taibbi, went on Mehdi Hasan’s show (which Taibbi explicitly demanded from Hasan, after Hasan asked about Taibbi’s opinions on Musk blocking accounts for Modi in India). The interview did not go well for Taibbi in the same manner that finding an iceberg did not go well for the Titanic.

One segment of the absolutely brutal interview involves Hasan asking Taibbi the very question that Taibbi had said he wanted to come on the show to answer: what was his opinion of Musk blocking Twitter accounts in India, including those of journalists and activists, that were critical of the Modi government? Hasan notes that Taibbi has talked up how he believes Musk is supporting free speech, and asked Taibbi if he’d like to criticize the blocking of journalists.

Taibbi refused to do so, and claimed he doesn’t really know about the story, even though it was the very story that Hasan initially tweeted about that resulted in Taibbi saying he’d tell Hasan his opinion on the story if he was invited on the show. It was, well, embarrassing to watch Taibbi squirm as he knew he couldn’t say anything critical about Musk. He already saw how the second Twitter Files scribe, Bari Weiss, was ex-communicated from the Church of Musk for criticizing Musk’s banning of journalists.

The conversation was embarrassing in real time:

Hasan: What’s interesting about Elon Musk is that, we’ve checked, you’ve tweeted over thirty times about Musk since he announced he was going to buy Twitter last April, and not a word of criticism about him in any of those thirty plus tweets. Musk is a billionaire who’s been found to have violated labor laws multiples times, including in the past few days. He’s attacked labor unions, reportedly fired employees on a whim, slammed the idea of a wealth tax. Told his millions of followers to vote Republican last year, and in response to a right-wing coup against Bolivian leftist President Evo Morales tweeted “we’ll coup whoever we want.”

And yet, you’ve been silent on all that.

How did you go, Matt, from being the scourge of Wall St. The man who called Goldman Sachs the Vampire Squid, to be unwilling to say anything critical at all about this right wing reactionary anti-union billionaire.

Taibbi: Look….[long pause… then a sigh]. So… so… I like Elon Musk. I met him. This is part of the calculation when you do one of these stories. Are they going to give you information that’s gonna make you look stupid. Do you think their motives are sincere about doing x or y…. I did. I thought his motives were sincere about the Twitter Files. And I admired them. I thought he did a tremendous public service in opening the files up. But that doesn’t mean I have to agree with him about everything.

Hasan: I agree with you. But you never disagree with him. You’ve gone silent. Some would say that’s access journalism.

Taibbi: No! No. I haven’t done… I haven’t reported anything that limits my ability to talk about Elon Musk…

Hasan: So will you criticize him today? For banning journalists, for working with Modi government to shut down speech, for being anti-union. You can go for it. I’ll give you as much time as you’d like. Would you like to criticize Musk now?

Taibbi: No, I don’t particularly want to… uh… look, I didn’t criticize him really before… uh… and… I think that what the Twitter Files are is a step in the right direction…

Hasan: But it’s the same Twitter he’s running right now…

Taibbi: I don’t have to disagree with him… if you wanna ask… a question in bad faith…

[crosstalk]

Hasan: It’s not in bad faith, Matt!

Taibbi: It absolutely is!

Hasan: Hold on, hold on, let me finish my question. You saying that he’s good for Twitter and good for speech. I’m saying that he’s using Twitter to help one of the most rightwing governments in the world censor speech. I will criticize that. Will you?

Taibbi: I have to look at the story first. I’m not looking at it now!

By Friday, that exchange became even more embarrassing. Because, due to a separate dispute that Elon was having with Substack (more on that in a bit), he decided to arbitrarily bar anyone from retweeting, replying, or even liking any tweet that had a Substack link in it. But Taibbi’s vast income stems from having one of the largest paying Substack subscriber bases. So, in rapid succession he announced that he was leaving Twitter, and would rely on Substack, and that this would likely limit his ability to continue working on the Twitter Files. Minutes later, Elon Musk unfollowed Taibbi on Twitter.

Quite a shift in the Musk/Taibbi relationship in 24 hours.

Then came Saturday. First Musk made up some complete bullshit about both Substack and Taibbi, claiming that Taibbi was an employee of Substack, and also that Substack was violating their (rapidly changing to retcon whatever petty angry outburst Musk has) API rules.

Somewhat hilariously, the Community Notes feature — which old Twitter had created, though once Musk changed its name from “Birdwatch” to “Community Notes,” he acted as if it was his greatest invention — is correcting Musk:

Because also either late Friday or early Saturday, Musk had added substack.com to Twitter’s list of “unsafe” URLs, suggesting that it may contain malicious links that could steal information. Of course, the only one malicious here was Musk.

Also correcting Musk? Substack founder Chris Best:

Then, a little later on Saturday, people realized that searching for Matt Taibbi’s account… turned up nothing. Taibbi wrote on Substack that he believed all his Twitter Files had been “removed” as first pointed out by William LeGate:

But, if you dug into Taibbi’s Twitter account, you could still find them. Mashable’s Matt Binder solved the mystery and revealed, somewhat hilariously, that Taibbi’s acount appears to have been “max deboosted” or, in Twitter’s terms, had the highest level of visibility filters applied, meaning you can’t find Taibbi in search. Or, in the parlance of today, he shadowbanned Matt Taibbi.

Again, this shouldn’t be a surprise, even though the irony is super thick. Early Twitter Files revealed that Twitter had long used visibility filtering to limit the spread of certain accounts. Musk screamed about how this was horrible shadowbanning… but then proceeded to use those tools to suppress speech of people he disliked. And now he’s using the tool, at max power, to hide Taibbi and the very files that we were (falsely) told “exposed” how old Twitter shadow banned people.

This is way more ironic than the Alanis song.

So, yes, we went from Taibbi praising Elon Musk for supporting free speech and supposedly helping to expose the evil shadowbanning of the old regime, and refusing to criticize Musk on anything, to Taibbi leaving Twitter, and Musk not just unfollowing him but shadowbanning him and all his Twitter Files.

In about 48 hours.

Absolutely incredible.

Just a stunning show of leopard face eating.

Not much happened then on Sunday, though Twitter first added a redirect on any searches for “substack” to “newsletters” (what?) and then quietly stopped throttling links to Substack, though no explanation was given. And as far as I can tell, Taibbi’s account is still “max deboosted.”

Anyway, again, to be clear: Elon Musk is perfectly within his rights to be as arbitrary and capricious as he wants to be with his own site. But can people please stop pretending his actions have literally anything to do with “free speech”?

Filed Under: content moderation, elon musk, matt taibbi, mehdi hasan, shadowbanning, twitter files, visibility filtering

Companies: substack, twitter

Mehdi Hasan Dismantles The Entire Foundation Of The Twitter Files As Matt Taibbi Stumbles To Defend It

from the i'd-like-to-report-a-murder dept

So here’s the deal. If you think the Twitter Files are still something legit or telling or powerful, watch this 30 minute interview that Mehdi Hasan did with Matt Taibbi (at Taibbi’s own demand):

Hasan came prepared with facts. Lots of them. Many of which debunked the core foundation on which Taibbi and his many fans have built the narrative regarding the Twitter Files.

We’ve debunked many of Matt’s errors over the past few months, and a few of the errors we’ve called out (though not nearly all, as there are so, so many) show up in Hasan’s interview, while Taibbi shrugs, sighs, and makes it clear he’s totally out of his depth when confronted with facts.

Since the interview, Taibbi has been scrambling to claim that the errors Hasan called out are small side issues, but they’re not. They’re literally the core pieces on which he’s built the nonsense framing that Stanford, the University of Washington, some non-profits, the government, and social media have formed an “industrial censorship complex” to stifle the speech of Americans.

As we keep showing, Matt makes very sloppy errors at every turn, doesn’t understand the stuff he has found, and is confused about some fairly basic concepts.

The errors that Hasan highlights matter a lot. A key one is Taibbi’s claim that the Election Integrity Partnership flagged 22 million tweets for Twitter to take down in partnership with the government. This is flat out wrong. The EIP, which was focused on studying election interference, flagged less than 3,000 tweets for Twitter to review (2,890 to be exact).

And they were quite clear in their report on how all this worked. EIP was an academic project to track election interference information and how it flowed across social media. The 22 million figure shows up in the report, but it was just a count of how many tweets they tracked in trying to follow how this information spread, not seeking to remove it. And the vast majority of those tweets weren’t even related to the ones they did explicitly create tickets on.

In total, our incident-related tweet data included 5,888,771 tweets and retweets from ticket status IDs directly, 1,094,115 tweets and retweets collected first from ticket URLs, and 14,914,478 from keyword searches, for a total of 21,897,364 tweets.

Tracking how information spreads is… um… not a problem now is it? Is Taibbi really claiming that academics shouldn’t track the flow of information?

Either way, Taibbi overstated the number of tweets that EIP reported by 21,894,474 tweets. In percentage terms, the actual number of reported tweets was 0.013% of the number Taibbi claimed.

Okay, you say, but STILL, if the government is flagging even 2,890 tweets, that’s still a problem! And it would be if it was the government flagging those tweets. But it’s not. As the report details, basically all of the tickets in the system were created by non-government entities, mainly from the EIP members themselves (Stanford, University of Washington, Graphika, and Digital Forensics Lab).

This is where the second big error that Taibbi makes knocks down a key pillar of his argument. Hasan notes that Taibbi falsely turned the non-profit Center for Internet Security (CIS) into the government agency the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Taibbi did this by assuming that when someone at Twitter noted information came from CIS, they must have meant CISA, and therefore he appended the A in brackets as if he was correcting a typo:

Taibbi admits that this was a mistake and has now tweeted a correction (though this point was identified weeks ago, and he claims he only just learned about it). I’ve seen Taibbi and his defenders claim that this is no big deal, that he just “messed up an acronym.” But, uh, no. Having CISA report tweets to Twitter was a key linchpin in the argument that the government was sending tweets for Twitter to remove. But it wasn’t the government, it was an independent non-profit.

The thing is, this mistake also suggests that Taibbi never even bothered to read the EIP report on all of this, which lays out extremely clearly where the flagged tweets came from, noting that CIS (which was not an actual part of the EIP) sent in 16% of the total flagged tweets. It even pretty clearly describes what those tweets were:

Compared to the dataset as a whole, the CIS tickets were (1) more likely to raise reports about fake official election accounts (CIS raised half of the tickets on this topic), (2) more likely to create tickets about Washington, Connecticut, and Ohio, and (3) more likely to raise reports that were about how to vote and the ballot counting process—CIS raised 42% of the tickets that claimed there were issues about ballots being rejected. CIS also raised four of our nine tickets about phishing. The attacks CIS reported used a combination of mass texts, emails, and spoofed websites to try to obtain personal information about voters, including addresses and Social Security numbers. Three of the four impersonated election official accounts, including one fake Kentucky election website that promoted a narrative that votes had been lost by asking voters to share personal information and anecdotes about why their vote was not counted. Another ticket CIS reported included a phishing email impersonating the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) that was sent to Arizona voters with a link to a spoofed Arizona voting website. There, it asked voters for personal information including their name, birthdate, address, Social Security number, and driver’s license number.

In other words, CIS was raising pretty legitimate issues: people impersonating election officials, and phishing pages. This wasn’t about “misinformation.” These were seriously problematic tweets.

There is one part that perhaps deserves some more scrutiny regarding government organizations, as the report does say that a tiny percentage of reports came from the GEC, which is a part of the State Department, but the report suggests that this was probably less than 1% of the flags. 79% of the flags came from the four organizations in the partnership (not government). Another 16% came from CIS (contrary to Taibbi’s original claim, not government). That leaves 5%, which came from six different organizations, mostly non-profits. Though it does list the GEC as one of the six organizations. But the GEC is literally focused entirely on countering (not deleting) foreign state propaganda aimed at destabilizing the US. So, it’s not surprising that they might call out a few tweets to the EIP researchers.

Okay, okay, you say, but even so this is still problematic. It was still, as a Taibbi retweet suggests, these organizations who are somehow close to the government trying to silence narratives. And, again, that would be bad if true. But, that’s not what the information actually shows. First off, we already discussed how some of what they targeted was just out and out fraud.

But, more importantly, regarding the small number of tweets that EIP did report to Twitter… it never suggested what Twitter should do about them, and Twitter left the vast majority of them up. The entire purpose of the EIP program, as laid out in everything that the EIP team has made clear from before, during, and after the election, was just to be another set of eyes looking out for emerging trends and documenting how information flows. In the rare cases (again less than 1%) where things looked especially problematic (phishing attempts, impersonation) they might alert the company, but made no effort to tell Twitter how to handle them. And, as the report itself makes clear, Twitter left up the vast majority of them:

We find, overall, that platforms took action on 35% of URLs that we reported to them. 21% of URLs were labeled, 13% were removed, and 1% were soft blocked. No action was taken on 65%. TikTok had the highest action rate: actioning (in their case, their only action was removing) 64% of URLs that the EIP reported to their team.)

They don’t break it out by platform, but across all platforms no action was taken on 65% of the reported content. And considering that TikTok seemed quite aggressive in removing 64% of flagged content, that means that all of the other platforms, including Twitter, took action on way less than 35% of the flagged content. And then, even within the “took action” category, the main action taken was labeling.

In other words, the top two main results of EIP flagging this content were:

- Nothing

- Adding more speech

The report also notes that the category of content that was most likely to get removed was the out and out fraud stuff: “phishing content and fake official accounts.” And given that TikTok appears to have accounted for a huge percentage of the “removals” this means that Twitter removed significantly less than 13% of the tweets that EIP flagged for them. So not only is it not 22 million tweets, it’s that EIP flagged less than 3,000 tweets, and Twitter ignored most of them and removed probably less than 10% of them.

When looked at in this context, basically the entire narrative that Taibbi is pushing melts away.

The EIP is not part of the “industrial censorship complex.” It’s a mostly academic group that was tracking how information flows across social media, which is a legitimate area of study. During the election they did exactly that. In the tiny percentage of cases where they saw stuff they thought was pretty worrisome, they’d simply alert the platforms with no push for the platforms to take any action, and (indeed) in most cases the platforms took no action whatsoever. In a few cases, they added more speech.

In a tiny, tiny percentage of the already tiny percentage, when the situation was most extreme (phishing, fake official accounts) then the platforms (entirely on their own) decided to pull down that content. For good reason.

That’s not “censorship.” There’s no “complex.” Taibbi’s entire narrative turns to dust.

There’s a lot more that Taibbi gets wrong in all of this, but the points that Hasan got him to admit he was wrong about are literally core pieces in the underlying foundation of his entire argument.

At one point in the interview, Hasan also does a nice job pointing out that the posts that the Biden campaign (note: not the government) flagged to Twitter were of Hunter Biden’s dick pics, not anything political (we’ve discussed this point before) and Taibbi stammers some more and claims that “the ordinary person can’t just call up Twitter and have something taken off Twitter. If you put something nasty about me on Twitter, I can’t just call up Twitter…”

Except… that’s wrong. In multiple ways. First off, it’s not just “something nasty.” It’s literally non-consensual nude photos. Second, actually, given Taibbi’s close relationship with Twitter these days, uh, yeah, he almost certainly could just call them up. But, most importantly, the claim about “the ordinary” person not being able to have non-consensual nude images taken off the site? That’s wrong.

You can. There’s a form for it right here. And I’ll admit that I’m not sure how well staffed Twitter’s trust & safety team is to handle those reports today, but it definitely used to have a team of people who would review those reports and take down non-consensual nude photos, just as they did with the Hunter Biden images.

As Hasan notes, Taibbi left out this crucial context to make his claims seem way more damning than they were. Taibbi’s response is… bizarre. Hasan asks him if he knew that the URLs were nudes of Hunter Biden and Taibbi admits that “of course” he did, but when Hasan asks him why he didn’t tell people that, Taibbi says “because I didn’t need to!”

Except, yeah, you kinda do. It’s vital context. Without it, the original Twitter Files thread implied that the Biden campaign (again, not the government) was trying to suppress political content or embarrassing content that would harm the campaign. The context that it’s Hunter’s dick pics is totally relevant and essential to understanding the story.

And this is exactly what the rest of Hasan’s interview (and what I’ve described above) lays out in great detail: Taibbi isn’t just sloppy with facts, which is problematic enough. He leaves out the very important context that highlights how the big conspiracy he’s reporting is… not big, not a conspiracy, and not even remotely problematic.

He presents it as a massive censorship operation, targeting 22 million tweets, with takedown demands from government players, seeking to silence the American public. When you look through the details, correcting Taibbi’s many errors, and putting it in context, you see that it was an academic operation to study information flows, who sent the more blatant issues they came across to Twitter with no suggestion that they do anything about them, and the vast majority of which Twitter ignored. In some minority of cases, Twitter applied its own speech to add more context to some of the tweets, and in a very small number of cases, where it found phishing attempts or people impersonating election officials (clear terms of service violations, and potentially actual crimes), it removed them.

There remains no there there. It’s less than a Potemkin village. There isn’t even a façade. This is the Emperor’s New Clothes for a modern era. Taibbi is pointing to a naked emperor and insisting that he’s clothed in all sorts of royal finery, whereas anyone who actually looks at the emperor sees he’s naked.

Filed Under: censorship, content moderation, eip, elections, matt taibbi, mehdi hasan, twitter files

Companies: twitter

Jim Jordan Weaponizes The Subcommittee On The Weaponization Of The Gov’t To Intimidate Researchers & Chill Speech

from the where-are-the-jordan-files? dept

As soon as it was announced, we warned that the new “Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government,” (which Kevin McCarthy agreed to support to convince some Republicans to support his speakership bid) was going to be not just a clown show, but one that would, itself, be weaponized to suppress speech (the very thing it claimed it would be “investigating.”)

To date, the subcommittee, led by Jim Jordan, has lived down to its expectations, hosting nonsense hearings in which Republicans on the subcommittee accidentally destroy their own talking points and reveal themselves to be laughably clueless.

Anyway, it’s now gone up a notch beyond just performative beclowing to active maliciousness.

This week, Jordan sent information requests to Stanford University, the University of Washington, Clemson University and the German Marshall Fund, demanding they reveal a bunch of internal information, that serves no purpose other than to intimidate and suppress speech. You know, the very thing that Jim Jordan pretends his committee is “investigating.”

House Republicans have sent letters to at least three universities and a think tank requesting a broad range of documents related to what it says are the institutions’ contributions to the Biden administration’s “censorship regime.”

As we were just discussing, the subcommittee seems taken in by Matt Taibbi’s analysis of what he’s seen in the Twitter files, despite nearly every one of his “reports” on them containing glaring, ridiculous factual errors that a high school newspaper reporter would likely catch. I mean, here he claims that the “Disinformation Governance Board” (an operation we mocked for the abject failure of the administration in how it rolled out an idea it never adequately explained) was somehow “replaced” by Stanford University’s Election Integrity Project.

Except the Disinformation Governance Board was announced, and then disbanded, in April and May of 2022. The Election Integrity Partnership was very, very publicly announced in July of 2020. Now, I might not be as decorated a journalist as Matt Taibbi, but I can count on my fingers to realize that 2022 comes after 2020.

Look, I know that time has no meaning since the pandemic began. And that journalists sometimes make mistakes (we all do!), but time is, you know, not that complicated. Unless you’re so bought into the story you want to tell you just misunderstand basically every last detail.

The problem, though, goes beyond just getting simple facts wrong (and the list of simple facts that Taibbi gets wrong is incredibly long). It’s that he gets the less simple, more nuanced facts, even more wrong. Taibbi still can’t seem to wrap his head around the idea that this is how free speech and the marketplace of ideas actually works. Private companies get to decide the rules for how anyone gets to use their platform. Other people get to express their opinions on how those rules are written and enforced.

As we keep noting, the big revelations so far (if you read the actual documents in the Twitter Files, and not Taibbi’s bizarrely disconnected-from-what-he’s-commenting-on commentary), is that Twitter’s Trust and Safety team was… surprisingly (almost boringly) competent. I expected way more awful things to come out in the Twitter Files. I expected dirt. Awful dirt. Embarrassing dirt. Because every company of any significant size has that. They do stupid things for stupid fucking reasons, and bend over backwards to please certain constituents.

But… outside of a few tiny dumb decisions, Twitter’s team has seemed… remarkably competent. They put in place rules. If people bent the rules, they debated how to handle it. They sometimes made mistakes, but seemed to have careful, logical debates over how to handle those things. They did hear from outside parties, including academic researchers, NGOs, and government folks, but they seemed quite likely to mock/ignore those who were full of shit (in a manner that pretty much any internal group would do). It’s shockingly normal.

I’ve spent years talking to insiders working on trust and safety teams at big, medium, and small companies. And, nothing that’s come out is even remotely surprising, except maybe how utterly non-controversial Twitter’s handling of these things was. There’s literally less to comment on then I expected. Nearly every other company would have a lot more dirt.

Still, Jordan and friends seem driven by the same motivation as Taibbi, and they’re willing to do exactly the things that they claim they’re trying to stop: using the power of the government to send threatening intimidation letters that are clearly designed to chill academic inquiry into the flow of information across the internet.

By demanding that these academic institutions turn over all sorts of documents and private communications, Jordan must know that he’s effectively chilling the speech of not just them, but any academic institution or civil society organization that wants to study how false information (sometimes deliberately pushed by political allies of Jim Jordan) flow across the internet.

It’s almost (almost!) as if Jordan wants to use the power of his position as the head of this subcommittee… to create a stifling, speech-suppressing, chilling effect on academic researchers engaged in a well-established field of study.

Can’t wait to read Matt Taibbi’s report on this sort of chilling abuse by the federal government. It’ll be a real banger, I’m sure. I just hope he uses some of the new Substack revenue he’s made from an increase in subscribers to hire a fact checker who knows how linear time works.

Filed Under: academic research, chilling effects, congress, intimidation, jim jordan, matt taibbi, nonsense peddlers, research, twitter files, weaponization subcommittee

Companies: clemson university, german marshall fund, stanford, twitter, university of washington

Matt Taibbi Can’t Comprehend That There Are Reasons To Study Propaganda Information Flows, So He Insists It Must Be Nefarious

from the not-how-any-of-this-works dept

Over the last few months, Elon Musk’s handpicked journalists have continued revealing less and less with each new edition of the “Twitter Files,” to the point that even those of us who write about this area have mostly been skimming each new release, confirming that yet again these reporters have no idea what they’re talking about, are cherry picking misleading examples, and then misrepresenting basically everything.

It’s difficult to decide if it’s even worth giving these releases any credibility at all in going through the actual work of debunking them, but sometimes a few out of context snippets from the Twitter Files, mostly from Matt Taibbi, seem to get picked up by others and it becomes necessary to dive back into the muck to clean up the mess that Matt has made yet again.

Unfortunately, this seems like one of those times.

Over the last few “Twitter Files” releases, Taibbi has been pushing hard on the false claim that, okay, maybe he can’t find any actual evidence that the government tried to force Twitter to remove content, but he can find… information about how certain university programs and non-governmental organizations received government grants… and they setup “censorship programs.”

It’s “censorship by proxy!” Or so the claim goes.

Except, it’s not even remotely accurate. The issue, again, goes back to understanding some pretty fundamental concepts that seem to escape Taibbi’s ability to understand. Let’s go through them.

Point number one: Studying misinformation and disinformation is a worthwhile field of study. That’s not saying that we should silence such things, or that we need an “arbiter of truth.” But the simple fact remains that some have sought to use misinformation and disinformation to try to influence people, and studying and understanding how and why that happens is valuable.

Indeed, I personally tend to lean towards the view that most discussions regarding mis- and disinformation are overly exaggerated moral panics. I think the terms are overused, and often misused (frequently just to attack factual news that people dislike). But, in part, that’s why it’s important to study this stuff. And part of studying it is to actually understand how such information is spread, which includes across social media.

Point number two: It’s not just an academic field of interest. For fairly obvious reasons, companies that are used to spread such information have a vested interest in understanding this stuff as well, though to date, it’s mostly been the social media companies that have shown the most interest in understanding these things, rather than say, cable news, even as some of the evidence suggests cable news is a bigger vector for spreading such things than social media.

Still, the companies have an interest in understand this stuff, and sometimes that includes these organizations flagging content they find and sharing it with the companies for the sole purpose of letting those companies evaluate if the content violate existing policies. And, once again, the companies regularly did nothing after noting that the flagged accounts didn’t violate any policies.

Point number three: governments also have an interest in understand how such information flows, in part to help combat foreign influence campaigns designed to cause strife and even violence.

Note what none of these three points are saying: that censorship is necessary or even desired. But it’s not surprising that the US government has funded some programs to better understand these things, and that includes bringing in a variety of experts from academia and civil society and NGOs to better understand these things. It’s also no surprise that some of the social media companies are interested in what these research efforts find because it might be useful.

And, really, that’s basically everything that Taibbi has found out in his research. There are academic centers and NGOs that have received some grants from various government agencies to study mis- and disinformation flows. Also, that sometimes Twitter communicated with those organization. Notably, many of his findings actually show that Twitter employees absolutely disagreed with the conclusions of those research efforts. Indeed, some of the revealed emails show Twitter employees somewhat dismissive of the quality of the research.

What none of this shows is a grand censorship operation.

However, that’s what Taibbi and various gullible culture warriors in Congress are arguing, because why not?

So, some of the organizations in questions have decided they finally need to do some debunking on their own. I especially appreciate the University of Washington (UW), which did a step by step debunker that, in any reasonable world, would completely embarrass Matt Taibbi for the very obvious fundamental mistakes he made:

False impression: The EIP orchestrated a massive “censorship” effort. In a recent tweet thread, Matt Taibbi, one of the authors of the “Twitter Files” claimed: “According to the EIP’s own data, it succeeded in getting nearly 22 million tweets labeled in the runup to the 2020 vote.” That’s a lot of labeled tweets! It’s also not even remotely true. Taibbi seems to be conflating our team’s post-hoc research mapping tweets to misleading claims about election processes and procedures with the EIP’s real-time efforts to alert platforms to misleading posts that violated their policies. The EIP’s research team consisted mainly of non-expert students conducting manual work without the assistance of advanced AI technology. The actual scale of the EIP’s real-time efforts to alert platforms was about 0.01% of the alleged size.

Now, that’s embarrassing.

There’s a lot more that Taibbi misunderstands as well. For example, the freak-out over CISA:

False impression: The EIP operated as a government cut-out, funneling censorship requests from federal agencies to platforms. This impression is built around falsely framing the following facts: the founders of the EIP consulted with the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) office prior to our launch, CISA was a “partner” of the EIP, and the EIP alerted social media platforms to content EIP researchers analyzed and found to be in violation of the platforms’ stated policies. These are all true claims — and in fact, we reported them ourselves in the EIP’s March 2021 final report. But the false impression relies on the omission of other key facts. CISA did not found, fund, or otherwise control the EIP. CISA did not send content to the EIP to analyze, and the EIP did not flag content to social media platforms on behalf of CISA.

There are multiple other false claims that UW debunks as well, including that it was a partisan effort, that it happened in secret, or that it did anything related to content moderation. None of those are true.

The Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO), which works with UW on some of these programs, ended up putting out a similar debunker statement as well. For whatever reason, the SIO seems to play a central role in Taibbi’s fever dream of “government-driven censorship.” He focuses on projects like the Election Integrity Project or the Virality Project, both of which were focused on looking at the flows of viral misinformation.

In Taibbi’s world, these were really government censorship programs. Except, as SIO points out, they weren’t funded by the government:

Does the SIO or EIP receive funding from the federal government?

As part of Stanford University, the SIO receives gift and grant funding to support its work. In 2021, the SIO received a five-year grant from the National Science Foundation, an independent government agency, awarding a total of $748,437 over a five-year period to support research into the spread of misinformation on the internet during real-time events. SIO applied for and received the grant after the 2020 election. None of the NSF funds, or any other government funding, was used to study the 2020 election or to support the Virality Project. The NSF is the SIO’s sole source of government funding.

They also highlight how the Virality Project’s work on vaccine disinformation was never about “censorship.”

Did the SIO’s Virality Project censor social media content regarding coronavirus vaccine side-effects?

No. The VP did not censor or ask social media platforms to remove any social media content regarding coronavirus vaccine side effects. Theories stating otherwise are inaccurate and based on distortions of email exchanges in the Twitter Files. The Project’s engagement with government agencies at the local, state, or federal level consisted of factual briefings about commentary about the vaccine circulating on social media.

The VP’s work centered on identification and analysis of social media commentary relating to the COVID-19 vaccine, including emerging rumors about the vaccine where the truth of the issue discussed could not yet be determined. The VP provided public information about observed social media trends that could be used by social media platforms and public health communicators to inform their responses and further public dialogue. Rather than attempting to censor speech, the VP’s goal was to share its analysis of social media trends so that social media platforms and public health officials were prepared to respond to widely shared narratives. In its work, the Project identified several categories of allegations on Twitter relating to coronavirus vaccines, and asked platforms, including Twitter, which categories were of interest to them. Decisions to remove or flag tweets were made by Twitter.

In other words, as was obvious to anyone who actually had followed any of this while these projects were up and running, these are not examples of “censorship” regimes. Nor are they efforts to silence anyone. They’re research programs on information flows. That’s also clear if you don’t read Taibbi’s bizarrely disjointed commentary and just look at the actual things he presents.

In a normal world, the level of just outright nonsense and mistakes in Taibbi’s work would render his credibility completely shot going forward. Instead, he’s become a hero to a certain brand of clueless troll. It’s the kind of transformation that would be interesting to study and understand, but I assume Taibbi would just build a grand conspiracy theory about how doing that was just an attempt by the illuminati to silence him.

Filed Under: academic research, censorship, cisa, disinformation, information flows, matt taibbi, misinformation, propaganda, twitter files

Companies: stanford, twitter, university of washington

Details Of FTC’s Investigation Into Twitter And Elon Musk Emerge… And Of Course People Are Turning It Into A Nonsense Culture War

from the closing-in dept

Back in the fall we were among the first to highlight that Elon Musk might face a pretty big FTC problem. Twitter, of course, is under a 20 year FTC consent decree over some of its privacy failings. And, less than a year ago (while still under old management), Twitter was hit with a $150 million fine and a revised consent decree. Both of them are specifically regarding how it handles users private data. Musk has made it abundantly clear that he doesn’t care about the FTC, but that seems like a risky move. While I think this FTC has made some serious strategic mistakes in the antitrust world, the FTC tends not to fuck around with privacy consent decrees.

However, now the Wall Street Journal has a big article with some details about the FTC’s ongoing investigation into Elon’s Twitter (based on a now released report from the Republican-led House Judiciary who frames the whole thing as a political battle by the FTC to attack a company Democrats don’t like — despite the evidence included not really showing anything to support that narrative).

The Federal Trade Commission has demanded Twitter Inc. turn over internal communications related to owner Elon Musk, as well as detailed information about layoffs—citing concerns that staff reductions could compromise the company’s ability to protect users, documents viewed by the Wall Street Journal show.

In 12 letters sent to Twitter and its lawyers since Mr. Musk’s Oct. 27 takeover, the FTC also asked the company to “identify all journalists” granted access to company records and to provide information about the launch of the revamped Twitter Blue subscription service, the documents show.

The FTC is also seeking to depose Mr. Musk in connection with the probe.

I will say that some of the demands from the FTC appear to potentially be overbroad, which should be a concern:

The FTC also asked for all internal Twitter communications “related to Elon Musk,” or sent “at the direction of, or received by” Mr. Musk.