An 11-step patch management process to ensure success (original) (raw)

Patch management refers to the process of acquiring software updates for OSes and applications and deploying them to eliminate security vulnerabilities, fix bugs or add new features. In spite of this seemingly simple definition, the patch management process can be quite complex.

There are a number of reasons behind this complexity, including the following:

- The number of OSes and applications that must be patched.

- The frequency with which vendors release new patches.

- Most organizations use a variety of devices, each of which is patched in a different way.

- Siloed workloads that must be patched manually.

- Legacy systems that serve a mission-critical purpose, but for which no official patches exist.

Besides tackling this complexity, organizations must figure out the best way to handle the logistics behind the patch management process. It's important to put a formal process in place that ensures every system receives the appropriate patches in a timely manner. At the same time, resource-strapped organizations need to consider how to handle patch management so the process results in the least possible administrative overhead to avoid overburdening IT staff.

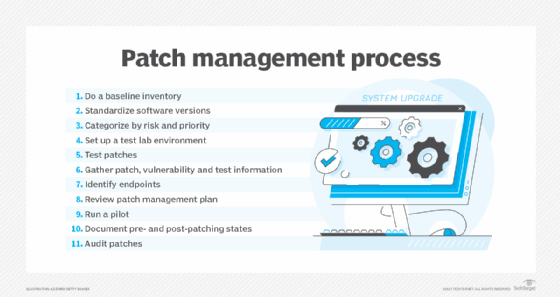

While the process of deploying a patch might be easy, performing organization-wide patch management in a consistent and reliable manner is anything but. Here are 11 key steps to get a handle on the patch management process and ensure its effectiveness.

1. Establish a baseline inventory

The first step is to establish an up-to-date baseline inventory of all your production systems so you can assess the current state of patching in the organization. The inventory must be comprehensive in scope and at a minimum should include all the OSes and applications your organization uses. It's also worth documenting the versions being used. You might find some systems are running outdated applications and need to be upgraded to a newer version as opposed to just being patched.

In addition to inventorying applications and OSes, you'll need to include firmware. Just as vendors release software updates designed to correct bugs and known vulnerabilities, hardware vendors periodically release firmware updates intended to address issues at the hardware level.

Depending on the size of your organization, you can collect the inventory manually or use automated patch management software for the job.

2. Have a plan to standardize systems to the same version type

Standardization is an important part of the patch management process. Having different versions of an application running in production drives up support costs and increases security risks. The same can be said for multiple versions of an OS. A major goal should be to determine the version of each OS and application your users should be running and come up with a plan to standardize on the preferred version.

The process sometimes involves more than just upgrading to the latest version. Dependencies across systems might have to be dealt with first. There might also be hardware requirements to consider. Windows 11 for example, requires a Trusted Platform Module 2.0 chip, and not every system that runs Windows 10 can support Windows 11. Hence, if Windows 11 is your preferred OS version, you will need to scrutinize your hardware inventory to ensure all your systems can support Windows 11.

3. Categorize each asset by risk and priority

During the initial phases of the patch management process, organizations will generally identify a number of upgrades that need to take place and patches that need to be applied. Performing all of these upgrades and patch deployments at the same time would be both chaotic and incredibly risky. Instead, organizations should take a methodical approach to the patch management process. This means assessing the vulnerabilities the various patches are designed to correct and prioritizing critical updates. The vast majority of patches for OSes and applications are designed to address some sort of security risk, but not all security risks are equally serious. Some might be quite minor, while others are critical and should be addressed first.

4. Use a test lab environment

Any time you deploy patches, there is the possibility a patch will cause problems. Before applying any patch to a production system, it should be thoroughly tested in a lab environment. You will need to determine whether the patch is safe for use or if it causes issues with mission-critical software. Even though software vendors presumably perform some level of patch testing, vendors are anxious to address security vulnerabilities quickly and might not test patches as thoroughly as they should. There have been numerous situations where software companies have released buggy patches that have introduced problems into environments that were working fine.

As you work through the patch testing process, keep in mind that problems aren't always going to be specific to the software you are upgrading. Problems could show up in another application that has a dependency on the software being patched. If, for example, you have a custom application that depends on Adobe Acrobat and apply a patch to Acrobat, there is a small chance the patch could break your custom application even if Acrobat continues to function normally.

Overview of the patch management process

5. Have the security team test patch stability

When testing a patch in the lab environment, it is important for the security team to confirm that the patch is stable and doesn't crash. At the same time, though, the security team should verify that the patch does indeed correct the vulnerability it was designed to protect against. The team should also work to make sure the patch doesn't introduce any new security vulnerabilities.

Your organization should establish a policy for how long patches should be tested in the lab environment. Almost every patch needs to be tested as thoroughly as possible, but the need for testing must be balanced against the vulnerability. Some organizations use a relatively short testing phase for critical patches but perform more in-depth testing for patches that are designed to address less serious vulnerabilities.

6. Gather software patch, vulnerability and test information

After completing the testing phase, the security team should compile a list of the patches that have been tested, the vulnerabilities those patches address and the outcome of the testing process. Those responsible for patch testing are essentially verifying that the testing process has been completed and making recommendations to the people responsible for deploying the patches.

7. Identify endpoints that need patching

The next step in the process is to determine which endpoints the patches need to be applied to. A good patch management application can help you keep track of the software running on each endpoint. That way, you can use a filter to obtain a list of the systems that should receive a particular patch.

8. Review, approve and mitigate patch management

At this point, there needs to be a formal review process in which the people responsible for managing the software consider the patch to be deployed, the results of the testing process and the list of endpoints tentatively slated to receive the patch. With this information, they can decide whether to approve deploying the patch.

If the team decides not to deploy a particular patch, the organization's patch management software will need to be configured to prevent that patch from being deployed. This is an essential step that keeps unwanted patches from being installed accidentally, whether by a well-intentioned staff member or by an automated process such as Windows Update.

9. Do a pilot deployment on a sample of patches

Even though one of the main goals of the patch management process is to standardize around a specific software version, few organizations roll out patches to all users at the same time. Instead, organizations will commonly do a pilot deployment to a representative sample of the user base before going ahead with an organization-wide deployment. The pilot deployment helps to verify that the patch is indeed safe for production use and gives the organization one last chance to catch any issues that didn't surface in lab tests. If an issue is found, only a relatively small number of endpoints will be affected, since the patch is yet to be deployed across the organization.

10. Document systems pre- and post-patching

It's important to document the state of your systems both before and after a patch is applied. If problems occur later, you might be able to find a correlation between when the problem began and a patch that was deployed just prior to the start of the problem.

11. Perform regular patch audits

It's important to repeat inventory collection on a regular basis. Otherwise, some systems might not have all the necessary patches, despite your best efforts. If the organization deploys a new system, for example, someone could forget to link it to the patch management software and cause software running on the new system to become outdated.

Another reason why systems might be found to be missing critical patches is because patch management software can occasionally fail. For example, a system might be turned off right when a patch is scheduled to be applied. A comprehensive patch audit is the best way to identify missing patches.

Patches can also go missing as a result of the backup and recovery process. If a system is restored from backup, for example, the restoration essentially reverts the system to the state it existed in at a previous point in time. As such, it's possible a restoration could roll a system back to its pre-patched state.

By carefully following this patch management process, your organization can gain the benefits of patches while minimizing the risks of deploying them. With a well-executed process, your systems will have the latest features and be largely free of bugs and security vulnerabilities. Plus, your IT and security teams will have peace of mind knowing they have a process they can count on that is predictable and relatively stress free.

Brien Posey is a 22-time Microsoft MVP and a commercial astronaut candidate. In his over 30 years in IT, he has served as a lead network engineer for the U.S. Department of Defense and as a network administrator for some of the largest insurance companies in America.