Building an incident response framework for your enterprise (original) (raw)

Incident response coordinates approaches to manage cyber incidents and fallout to limit their consequences. Incident response frameworks guide the direction and definition of response preparedness, planning and execution by outlining and detailing its elements, steps and stages.

Let's examine the importance of using an incident response framework and look at three options from NIST, ISO and SANS Institute.

Why is an incident response framework important?

The number of cybersecurity breaches continues to mount. Exposure must, therefore, be reined in.

When attackers hit their targets, consumers flee, and state and federal agencies investigate, file and win legal claims in the millions of dollars. Malicious hackers can compromise tens of millions of credit cards, leading to hundreds of millions of dollars in costs. Breaches can cost C-level executives their jobs. Settlements require companies to institute additional security measures and undergo greater scrutiny. After a breach, years of negative press are almost guaranteed, and damage control is critical.

These costs are driving organizations to adopt real-time incident response techniques that limit damage and reduce recovery time and costs. Generally, the better the incident response process, the better the outcome will be.

Failing at incident response can happen in many ways, which can add to the losses. To avoid making mistakes during incident response, organizations should look to credible incident response frameworks. Organizations can use these frameworks to refine an incident response plan, avoid response missteps and cap the casualties of the next breach.

Incident response framework vs. incident response plan

A framework provides a conceptual structure. An incident response framework, therefore, provides a structure to support incident response operations. A framework typically provides guidance on what needs to be done but not on how it is done. A framework is also loose and flexible to let elements be added or removed as necessary to satisfy a particular organization or constituency.

A plan is a detailed set of steps intended to achieve a goal. A plan might also list the resources required and the roles and responsibilities that must be supported and carried out to achieve its goals. An incident response plan, therefore, has the goal of delivering effective incident response. It details the processes needed to deal with computer security incidents, resources required, and communication and escalation paths required for plan operation.

Plans and frameworks should work together. The framework suggests logical elements to include in a plan, while a plan includes those elements, as well as elements of mission, services, people, process, technology and facilities.

With these distinctions in mind, it helps to understand three of the most well-known incident response frameworks to determine the best approach for your organization.

1. NIST incident response framework

NIST, part of the U.S. Department of Commerce, published its incident response framework, NIST Special Publication 800-61 Revision 2 -- Computer Security Incident Handling Guide, in the form of an incident response lifecycle.

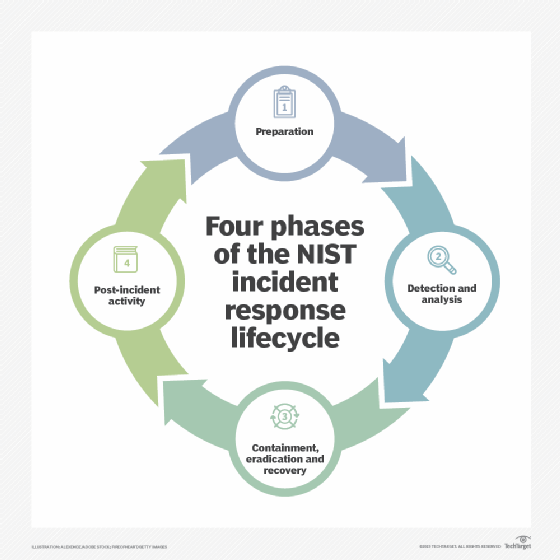

Follow the four phases of NIST's incident response framework to mitigate cyberthreats.

The four stages of the NIST incident response lifecycle are preparation; detection and analysis; containment, eradication and recovery; and post-incident activity.

Phase 1: Preparation

The quality of incident response largely depends on incident response preparation. The first phase of the lifecycle involves identifying, creating or acquiring all the components needed to respond effectively to a computer security incident.

Preparation includes the following:

- Establishing an incident management capability, process and plan.

- Creating incident response policies and procedures.

- Acquiring and training incident response staff.

- Acquiring incident-handling tools and training.

- Building an incident tracking system.

- Creating incident reporting policies and processes.

- Determining incident detection policies, processes, tools and procedures.

Phase 2: Detection and analysis

While the capability to detect incidents is set up as part of the preparation phase, incident detection starts the incident response process.

Detection focuses on discovering indicators of compromise. Network and system users notice many incident indicators, so it is critical to have an incident reporting policy and procedure. Users need to know what kinds of activities or indicators they should note, and they should have an easy reporting process.

The following tools and monitoring systems are also key to incident detection:

- Firewalls.

- Intrusion detection systems and intrusion prevention systems.

- Network traffic analysis systems.

- SIEM tools.

Incident analysis begins with taking the incident indicators from the detection phase and validating that an incident has occurred. Incident analysts are responsible for investigating ambiguous, incomplete, contradictory or erroneous indicators. Given this difficult task, NIST recommends building a team of highly skilled and experienced staff to determine what happened.

Phase 3: Containment, eradication and recovery

Containment follows the detection and validation of a security incident. The goals of containment are to stop the problem from getting worse -- i.e., limit the damage -- and to regain control of systems and networks.

NIST recommends creating containment strategies in advance according to factors such as major incident types, email, network and malware to facilitate decision-making.

Eradication is the elimination of the components of an incident. It includes removing malware, eliminating malicious user accounts and identifying vulnerabilities exploited during the security incident.

Recovery is the restoration of systems to normal operation following a security incident. Recovery tasks include restoring files from backups, reinstalling application software from known-good media, mitigating vulnerabilities identified in the eradication phase and changing passwords.

Phase 4: Post-incident activity

Post-incident activity centers on lessons learned to improve the incident response capability and prevent the incident from reoccurring. Ask the following questions during the post-incident phase:

- What happened exactly?

- What worked or didn't work well?

- Which procedures failed or failed to scale to respond to the incident?

- Which staff roles worked and were performed appropriately?

- Were any mistakes made that impeded recovery?

- What staff actions could be improved?

- Which policies and procedures could be improved?

- How could this incident have been avoided?

2. ISO incident response framework

ISO, an independent, nongovernmental international standards organization, published the two-part ISO/IEC 27035-1:2023 Information technology -- Information security incident management. Part 1 introduces incident management principles; Part 2 focuses on incident management preparation and planning.

The standard outlines the principles underlying information security incident management, broken out into the following five areas:

- Planning and preparation. During this step, establish an information security incident management policy, and create an incident response team.

- Detection and reporting. Set up the processes, procedures and technologies required to detect and report the incident.

- Assessment and decision. Set up processes and procedures, and establish incident descriptions and criteria.

- Response to incidents. Establish controls to prevent, respond and recover from incidents.

- Lessons learned. Learn from security incidents, and improve overall computer security incident management.

NIST and ISO/IEC 27035-1 overlap significantly. An important but subtle difference is that the NIST framework focuses on incident handling, which deals with the prevention, detection and response to incidents, but ISO's framework focuses on incident management, which is integrated broadly into other business management and risk reduction functions outside of the incident response organization.

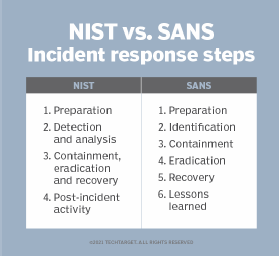

See how NIST and SANS Institute incident response frameworks compare.

3. SANS Institute incident response framework

SANS Institute, a private cybersecurity training, certification and research company, published a framework with the following six components:

- Preparation. Review and codify security policies, perform a risk assessment, identify sensitive assets, define critical security incidents and build a computer security incident response team.

- Identification. Monitor IT systems, detect deviations from normal operations and decide if they represent real security incidents. If an incident is discovered, collect additional evidence, establish its type and severity, and document everything.

- Containment. Perform short-term containment, and then focus on long-term containment, which involves temporary fixes to enable systems to be used in production while rebuilding clean systems.

- Eradication. Remove malware from affected systems, identify the root cause of the attack and take action to prevent similar attacks.

- Recovery. Bring affected production systems back online cautiously to prevent further attacks. Test, verify and monitor affected systems to ensure they are back to normal activity.

- Lessons learned. No later than two weeks from the end of the incident, compile all relevant information about the incident, and identify lessons that will help with future incident response activity.

SANS Institute offers the following general parameters for an incident report:

- When the problem was first detected and by whom.

- The scope of the incident.

- How it was contained and eradicated.

- Work performed during recovery.

- Areas where the computer incident response teams were effective.

- Areas that need improvement.

Other incident response frameworks

Additional cross-industry incident response frameworks are available, such as IEEE, Internet Engineering Task Force and European Union Agency for Cybersecurity. These frameworks can provide guidance and updates. Familiarize yourself and your incident response plan team with these frameworks.

It is important to contact standards and member organizations in the industry about their frameworks and to ask your vendors for guidance on their hardware, software and services and the different applications you use. Most vendors have frameworks to handle security incidents in their environments.

How to build and customize an incident response plan

Start by assimilating incident response frameworks from recognized standards organizations, such as NIST, ISO and SANS Institute. All incident management and response frameworks have a common lineage that can be traced back to the original computer emergency response team, CERT Coordination Center, and its five-part framework:

- Prepare. The first step involves the establishment of an incident management function and development of core processes and tools.

- Protect. This step covers risk assessment, prevention process and technology, operational exercises for incident management, training and guidance, and vulnerability management.

- Detect. This stage focuses on network and systems monitoring, as well as threat and situational awareness.

- Respond. Incident reporting,incident analysis and incident response are all functions of this stage.

- Sustain. The final step of the framework includes program and project management, as well as security administration.

Which framework should you choose? Should you choose one framework in its entirety, or should you choose part of one and combine it with parts of another framework for an a la carte kind of incident response?

When considering whether to adopt a framework as is or build your own, here are some things to think about.

What compliance obligations do you have that could affect your choice? Do you have obligations under the Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA)? Maybe you are a U.S. federal government supplier, and you must supply FISMA-complaint services. If so, go with NIST guidance because NIST has the statutory responsibility under FISMA to develop information security standards and guidelines.

Perhaps you do business outside of the U.S. in Europe or the Middle East. In that case, you should look at ISO/IEC 27035-1 because the ISO/IEC 27000 family of security standards is almost universally adopted in these regions. Or you might choose to go with the ISO/IEC 27000 family of standards to integrate security more easily into other business functions.

Other than these considerations, it's difficult to recommend one incident response framework over another. The bottom line is that a framework provides a structure that underlays and supports incident response operations. No matter which framework your organization chooses, the incident response operational plan -- not the framework itself -- is what your organization is going to use to protect itself and guide its incident management activities to discover and contain breaches.

David Geer writes about security and enterprise technology for international trade and business publications.

Peter Sullivan began his career in network operations, information security and incident response 20 years ago with the U.S. Army. Sullivan has been a visiting scientist at the Software Engineering Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, where he taught courses in risk management, information security and assurance, computer security incident response and digital forensics.