‘Radical Chic’: Still Cringey After All These Years (original) (raw)

Politics

Like author Tom Wolfe's caustic take in 1970, radicalism is being cultivated today in the best penthouses and corporate suites.

The radicals are on the march. Inspired by Antifa and Black Lives Matter, wokesters are trying to de-fund the police—and winning votes in cities such as Minneapolis. Moreover, they’re shaking up newsrooms and getting top editors fired.

Yet even as the Woken are challenging the establishment, they’re facing an interesting reaction—they’re being embraced, and funded, by that establishment.

Needless to say, Hollywood-type celebrities have been all over the new cause. Model-influencer Chrissy Teigen tweeted that she’d donate 100,000tohelpbailoutthosearrestedinMinneapolis,andwhenchallengedaboutit,sheuppedhercommitmentto100,000 to help bail out those arrested in Minneapolis, and when challenged about it, she upped her commitment to 100,000tohelpbailoutthosearrestedinMinneapolis,andwhenchallengedaboutit,sheuppedhercommitmentto200,000. And she has been joined, of course, by many other celebrities with money to burn; support for the protests—and, let’s not kid ourselves, support for the riots—has become a haute status symbol.

Moreover, these glittering radicals are being joined by much of corporate America. For instance, Amazon—not always known for its good treatment of minority workers at its shipping facilities, or for its sensitivity to racial stereotypes—has loudly endorsed Black Lives Matter. Indeed, CEO Jeff Bezos proclaims that he’s “happy to lose” customers that don’t join him in supporting the cause.

Yet the peak of 2020 corporate wokeness, at least so far, came when Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase, posed for the camera while taking a knee … in front of a bank vault. (We can observe that there’s a limit here; Dimon was posing in front of the vault, not throwing it open.)

Still, we can ask: What gives, when radicals and the rich are on the same side, at least optically? Students of history might recall that such alliances have been common in the past; for instance, in the Roman republic of the second century BCE, two patrician brothers, Gaius Gracchus and Tiberius Gracchus, sought to outflank their fellow aristocrats by making an alliance with the plebeians. The Gracchi failed, both dying violent deaths, but the concept of a high-low league has endured—and oftentimes has succeeded.

Here in America, for instance, we might think of such recent figures as Nelson Rockefeller and Teddy Kennedy; both of these rich men declared themselves to be champions of the non-rich, and both built upstairs-downstairs coalitions that brought them to high office—and close to the presidency.

Indeed, as we consider the current relationship between plutocrat George Soros and all the plebs he funds, we can see that the rich and the poor can still form an alliance—typically for the purpose of pincering the middle class.

One of the most insightful—and certainly the most entertaining—takes on the symbiotic relationship between plutocracy and poverty came from the writer Tom Wolfe. Wolfe is most famous for two books, The Right Stuff, his admiring 1979 history of the early space program, and The Bonfire of the Vanities, his caustic 1987 novel about greed and corruption in New York City.

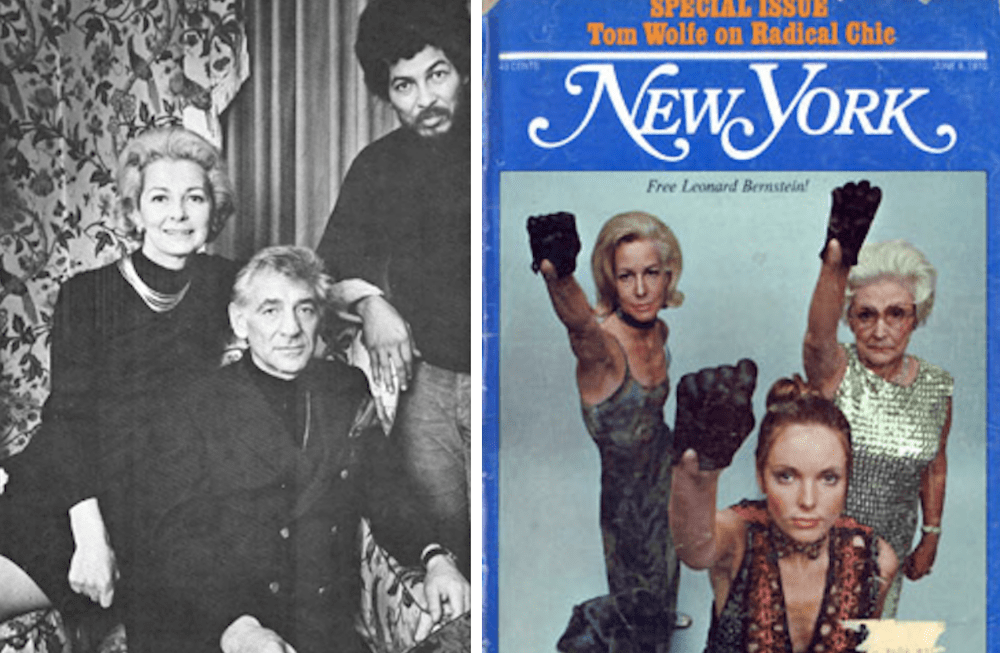

Yet we can focus on another of Wolfe’s writings, a 7,000-word article appearing in the June 8, 1970 issue of New York magazine, entitled, “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s.” In the title, “that party at Lenny’s” refers to a fundraiser for the Black Panthers—the Black Lives Matter of a half-century ago, a lineage BLM celebrates—held at famed conductor Leonard Bernstein’s swank Manhattan apartment.

And “radical chic” was Wolfe’s snarky label for rich people pretending to be revolutionaries, when, in fact, they were play-acting radicalism for the sake of raising their social status. That is, leftier-than-thou politics became a new sort of one-upsmanship.

As Wolfe explained, New York’s socialites “have always paid their dues to ‘the poor,’ via charity, as a way of claiming the nobility inherent in noblesse oblige and of legitimizing their wealth.” Continuing, he added, “In 1965 two new political movements, the anti-war movement and black power, began to gain great backing among culturati in New York.”

As for black power, a mutant sprout from the civil rights movement, Wolfe allowed that “one does have a sincere concern for the poor and the underprivileged and an honest outrage against discrimination.” And yet at the same time, “one also has a sincere concern for maintaining a proper East Side lifestyle in New York Society.”

And part of that lifestyle-maintenance was espousing the right—which is to say, trendy left—positions on key issues. In Wolfe’s words, the embrace of these causes served the purpose of “certifying their superiority over the hated ‘middle class.’”

By now, the reader will have gathered that Wolfe was not a fan of such posturing. In fact, he was not only a poisoned-pen critic, but also a deep-dyed conservative.

Still, for a while at least, Wolfe’s right-wing views were obscured by his anarchic New Journalism prose-style, relying heavily on streams of consciousness, irregular capitalization, lots of exclamation points, and spelled-out sound effects. For instance, his 1963 article for Esquire about car customizers was headlined, “There Goes (VAROOM! VAROOM!) that Kandy Kolored (THPHHHHHH!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (RAHGHHHH!) Around the Bend (BRUMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM…)”

So probably Leonard and Felicia Bernstein let Wolfe come to their Black Panther party, not realizing what he actually believed.

Yet in his 1970 article, Wolfe put down his cards. He wrote that the smart-set attendees were really practicing a safely distanced white tourism; that is, in their romanticization of the Black Panthers and other Radicals of Color, they were seeking out the thrill of hanging out, briefly, with “the styles of romantic, raw-vital, Low Rent.”

And Wolfe was just getting warmed up: “Radical Chic invariably favors radicals,” he wrote. It lionizes the the “exotic and romantic, such as the grape workers, who are not merely radical … but also Latin; the Panthers, with their leather pieces, Afros, shades, and shoot-outs; and the Red Indians, who, of course, had always seemed … exotic and romantic.”

Then Wolfe pressed further his critique of the chic: “All three groups had something else to recommend them, as well: they were headquartered 3,000 miles away from the East Side of Manhattan, in places like Delano (the grape workers), Oakland (the Panthers) and Arizona and New Mexico (the Indians).” In other words, Manhattanites could enjoy their flirtation with radicalism without having to travel west of the Hudson River.

In that party at Lenny’s, the special guests were a dozen or so Black Panthers. According to Wolfe, “The emotional momentum was building rapidly when Ray ‘Masai’ Hewitt, the Panthers’ Minister of Education and member of the Central Committee, rose to speak.” He observes: “Hewitt was an intense, powerful young man and in no mood to play the diplomacy game. Some of you here, he said, may have some feelings left for the establishment, but we don’t. We want to see it die. We’re Maoist revolutionaries, and we have no choice but to fight to the finish.”

Okay, so that spiel was quite a thrill for the chic. But maybe also, it was a bit too radical. Wolfe closes with the nervous reaction to Hewitt’s anger: “More than one Park Avenue matron was thrown into a Radical Chic confusion. The most memorable quote was: ‘He’s a magnificent man, but suppose some simple-minded schmucks take all that business about burning down buildings seriously?’”

In other words, radicalism is cool, but let’s not let the schmucks get carried away—at least not in my neighborhood.

Of course, protests do sometime get carried away; they turn into riots, destroy cities—and generate fierce backlashes. And Wolfe, his rarified mien notwithstanding, was a part of that backlash.

Alas, Wolfe died in 2018, and so we can only imagine what he’d be writing, today, about Radical Chic 2.0.

In the meantime, radicalism is being funded and cultivated in Manhattan and other ritzy precincts—not only in penthouses, but now, too, in corporate C-suites.

So perhaps there’s a Tom Wolfe 2.0 out there, observing all this wealthy woke posing—and hopefully recording it all on a surreptitious cell phone.